Abstract

Objective

To investigate the prevalence of seizures/febrile seizures in children up to 3 years of age and examine the effects of gestational age at birth on the risk for febrile seizures.

Design

Retrospective longitudinal population-based cohort study.

Setting

Kobe City public health center, Kobe, Japan, from 2010 to 2018.

Participants

Children who underwent a medical check-up at 3 years of age.

Methods

Information regarding seizures was collected from the parents of 96 014 children. We identified the occurrence of seizure/febrile seizure in 74 017 children, whose gestational ages at birth were noted. We conducted a multivariate analysis with the parameter, gestational age at birth, to analyse the risk of seizure. We also stratified the samples by sex and birth weight (<2500 g or not) and compared the prevalence of seizure between those with the term and late preterm births.

Results

The prevalence of seizure was 12.1% (11.8%–12.3%), 13.2% (12.2%–14.4%), 14.6% (12.4%–17.7%) and 15.7% (10.5%–22.8%) in children born at 37–41, 34–36, 28–33 and 22–27 gestational weeks, respectively. The prevalence of febrile seizures was 9.0% (8.8%–9.2%), 10.5% (9.5%–11.5%), 11.8% (9.7%–14.5%) and 11.2% (6.9%–17.7%) in children born at 37–41, 34–36, 28–33 and 22–27 gestational weeks, respectively. Male was an independent risk factor for seizures (OR: 1.15, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.20; absolute risk increase 0.014, 95% CI 0.010 to 0.019) and febrile seizures (OR: 1.21, 95% CI 1.15 to 1.28; absolute risk increase 0.016, 95% CI 0.012 to 0.020), respectively. Late preterm birth was not associated with an increased risk of seizure/febrile seizure.

Conclusions

Although very preterm birth may increase the risk of seizure/febrile seizure, the risk associated with late preterm birth is considerably small and less than that associated with male.

Keywords: neurology, epidemiology, neonatology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the largest study reporting on the prevalence of seizures and febrile seizures in East Asia.

This population-based study covers more than 95% of 3-year-old children, who lived in Kobe during the study period.

The longitudinal follow-up system enables birth data and seizure information to be collectively analysed.

Research via questionnaires from parents limits the accuracy of information.

Our study is limited by the lack of detailed clinical data on seizures.

Introduction

Seizures represent transient episodes of neuronal hyperactivity in the brain.1 Seizures, including febrile seizures, often occur in children, peaking at 1 year of age.2–5 The prevalence of afebrile seizures is thought to be around 1% among children.2 6 7 In contrast, the prevalence of febrile seizures varies geographically and is reportedly 2%–5% in the USA and Europe6 8–10 and 8%–11% in East Asia.7 11 These geographical differences can be attributed mainly to genetic factors, although several studies have focused on the environmental risk factors.5 8 9 11–17 Prenatal exposure to low levels of cigarette smoke, low-to-moderate levels of alcohol and any level of caffeine are not the risk factors for febrile seizures.8 In contrast, several studies report that prenatal and perinatal factors, including low birth weight (BW) and very preterm birth, increased the risk of febrile seizures.5 17 Conversely, other studies found that low BW is not associated with an increased risk of febrile seizures.9 11

The number of late preterm infants, defined as those born at 34–36 weeks’ gestational age (GA), has recently increased. The proportion of late preterm births among the total number of births increased from 7.3% in 1990 to 9.1% in 2005 in the USA, whereas the proportion of preterm births between 32 weeks and 36 weeks of GA in Japan, including late preterm birth, increased from 3.6% in 1980 to 5.0% in 2012.18 19 Since late preterm infants have a higher risk of morbidity and mortality, compared with full-term infants, their health outcomes have recently garnered attention.18 However, the effect of late preterm birth on the risk of seizures and febrile seizures has not been clarified. The objectives of this population-based study were to: (1) identify the prevalence of seizures and febrile seizures in children aged up to 3 years, (2) analyse the risk factors for seizures and febrile seizures according to GA and other birth information and (3) determine whether late preterm birth increases the risk of febrile seizure.

Patients and methods

Study design and participants

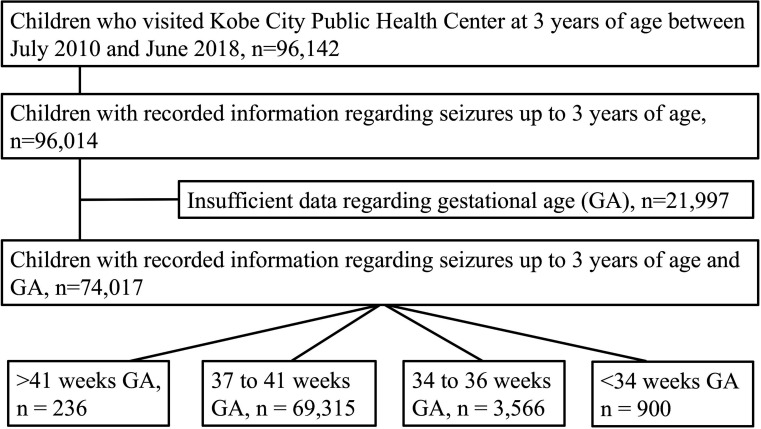

This was a retrospective longitudinal population-based cohort study (Kobe, Japan) based on several visits, including the neonatal visit and medical check-up at 3 years of age.19 20 According to the government rule, all children, including those with severe illness, were invited for a physical check-up at 3 years of age to detect early physical problems and receive appropriate health guidance. A total of 100 238 children, determined to be 3 years of age according to the population registry, were invited for a physical examination during the study period. Of these, 96 142 children visited the Kobe City public health center at 3 years of age, between July 2010 and June 2018 (figure 1). Therefore, this study included the physical examinations conducted for 95.9% of the 3-year-old children who lived in Kobe during the study period. Birth data, including sex, GA, BW, birth length (BL) and head circumference at birth (HC), were obtained from the maternal health records that were managed by the Kobe City public health centers. Information regarding seizures was collected from questionnaires, which was further confirmed by public health nurses and paediatricians when the children visited the Kobe City public health centers. The questionnaires enquired any experience of seizure, febrile seizure, afebrile seizure and the date of the first seizure after birth. Information regarding seizures up to 3 years of age was recorded for 96 014 children. Of these, 21 997 were excluded due to insufficient GA data. Finally, the data of 74 017 children were included in our analysis: 236 children born at >41 weeks’ GA, 69 315 children born at 37–41 weeks’ GA (full-term infants), 3566 children born at 34–36 weeks’ GA (late preterm infants) and 900 children born at <34 weeks’ GA.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the participants. GA, gestational age.

Analyses were performed at the Kobe University Graduate School of Medicine. The study was carried out according to the approved guidelines.

Patient and public involvement

The prevalence of seizures and febrile seizures, especially in preterm birth babies, is currently unknown in Japan. For public health, the study questions described earlier are highly relevant and have a high priority. This research did not include the recruitment of patients but rather used the data from participants who visited the Kobe City public health center at 3 years of age. The public was not invited to comment on the study design and was not consulted in the development of relevant outcomes or for the interpretation of the results. Study results will be disseminated to the participants by publication in peer-reviewed journals and be communicated to the public.

Data analyses

We analysed the population characteristics and compared the data of children who had experienced seizures with those who had not. Second, we identified the prevalence of seizure, febrile seizure and afebrile seizure according to birth information including GA. We also identified the age at which the first seizure, febrile seizure or afebrile seizure occurred. Third, we analysed the risk factors for seizures and febrile seizures among the variables at birth, in children born between 34 and 41 weeks’ GA. Finally, we divided the participants according to sex (male or female) and BW (<2500 g or not). Subsequently, we identified the incidence of seizures and febrile seizures and compared the data obtained from full-term and preterm infants.

Statistics

Results were expressed as number (%) or mean (SD). Incidence was presented as a percentage with 95% CI. The Mann-Whitney U test or Fisher’s exact test was used, where appropriate, for statistical analyses. We used multiple logistic regression to identify the risk factors for seizures or febrile seizures. The results were presented as the OR with 95% CI and an absolute risk increase (ARI) with 95% CI. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant for all tests. Analyses were performed using JMP, V.13.0.

Results

Prevalence of seizures and population demographics

The mean (SD) age of children, who visited the Kobe City public health centres and when the information regarding seizures was confirmed, was 3.32(0.08) years. Of 74 017 children, 8985 had experienced seizures, and the prevalence rate of seizures was 12.1% (95% CI 11.9% to 12.4%). From birth to 3 years of age, the number of children who had experienced febrile and afebrile seizures was 6743 and 673, respectively. The prevalence rates of febrile and afebrile seizures were 9.1% (95% CI 8.9% to 9.3%) and 0.9% (95% CI 0.8% to 1.0%), respectively. The remaining 1569 children also experienced seizures; however, the presence/absence of accompanying fever could not be confirmed. Participant characteristics are presented in table 1. Children with seizures were more likely to be male and preterm at birth, with low BW and lower HC.

Table 1.

Population characteristics

| All (n=74 017) | Seizure (n=8985) | No seizure (n=65 032) | P value | |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 37 684 (50.98)* | 4832 (53.82)† | 32 852 (50.52)‡ | <0.001 |

| Gestational age, weeks (SD) | 38.78 (1.68) | 38.74 (1.76) | 38.78 (1.67) | 0.371 |

| Preterm birth (<37 weeks), n (%) | 4466 (6.03) | 605 (6.73) | 3861 (5.94) | 0.003 |

| Birth weight, g (SD) | 2999 (423)§ | 2981 (435)¶ | 3001 (421)** | <0.001 |

| Low birth weight (<2500 g), n (%) | 917 (10.22)§ | 917 (10.22)¶ | 6062 (9.33)** | 0.008 |

| Birth length, cm (SD) | 48.52 (2.32)†† | 48.47 (2.42)‡‡ | 48.52 (2.30)§§ | 0.270 |

| Head circumference at birth, cm (SD) | 33.28 (1.59)¶¶ | 33.22 (1.62)*** | 33.28 (1.58)††† | 0.006 |

Information is available for a limited number of participants for several items.

*n=73 924.

†n=8978.

‡n=64 946.

§n=73 913.

¶n=8972.

**n=64 941.

††n=70 510.

‡‡n=8591.

§§n=61 919.

¶¶n=69 988.

***n=8531.

†††n=61 457.

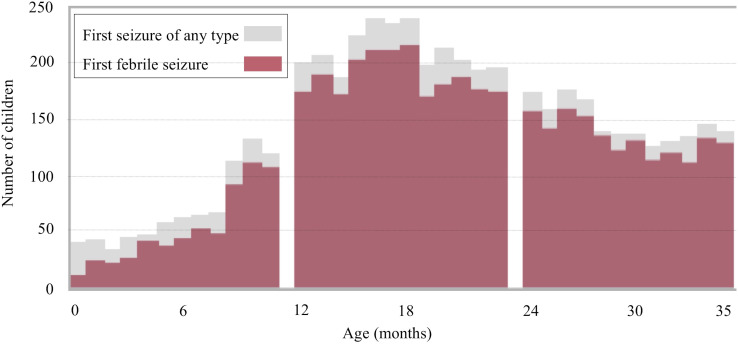

The age of occurrence of the first seizure of any type was identified in 5442 children (figure 2). The mean (SD) age when the first seizure occurred was 1.80 (0.80) years. A total of 2426 children experienced the first seizure between 1 and 2 years of age, 781 experienced it before 1 year and 1678 experienced it between 2 and 3 years of age. The age at the occurrence of the first febrile seizure and first afebrile seizure was identified in 4710 and 531 children, respectively. The mean (SD) age when the first febrile seizure occurred was 1.83 (0.77) years. The number of children who had the first febrile seizure aged <1, 1 and 2 years was 567, 2155 and 1515, respectively. The mean (SD) age for first afebrile seizure occurrence was 1.44 (0.89) years. The number of children who had the first afebrile seizure aged <1, 1 and 2 years was 175, 208 and 115, respectively.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the first seizure of any type and the first febrile seizure.

Table 2 presents febrile and afebrile seizure rates in children of ages up to 3 years, according to the findings at birth. Both seizures and febrile seizures were likely to be predominant in boys with lower GA, lower BW, lower BL and lower HC.

Table 2.

Febrile and afebrile seizure rates for up to 3 years of age, according to birth findings

| N | Prevalence of seizure, % (95% CI) | Prevalence of febrile seizure, % (95% CI) | Prevalence of afebrile seizure, % (95% CI) | Prevalence of seizure without known cause, % (95% CI) | |

| Total | 74 017 | 12.1 (11.9 to 12.4) | 9.1 (8.9 to 9.3) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) | 2.1 (2.0 to 2.2) |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 37 684 | 12.8 (12.5 to 13.2) | 9.9 (9.6 to 10.2) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) | 2.1 (1.9 to 2.2) |

| Female | 36 240 | 11.4 (11.1 to 11.8) | 8.3 (8.0 to 8.6) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) | 2.2 (2.0 to 2.3) |

| Gestational age at birth, weeks | |||||

| 22–27 | 134 | 15.7 (10.5 to 22.8) | 11.2 (6.9 to 17.7) | 2.2 (0.8 to 6.4) | 2.2 (0.8 to 6.4) |

| 28–33 | 766 | 14.6 (12.4 to 17.7) | 11.8 (9.7 to 14.5) | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.4) | 1.6 (1.0 to 3.0) |

| 34–36 | 3566 | 13.2 (12.2 to 14.4) | 10.5 (9.5 to 11.5) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.5) | 1.6 (1.3 to 2.1) |

| 37–41 | 69 315 | 12.1 (11.8 to 12.3) | 9.0 (8.8 to 9.2) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) | 2.2 (2.1 to 2.3) |

| 42–43 | 236 | 12.3 (9.0 to 16.4) | 10.6 (7.6 to 14.6) | 0.3 (0.1 to 1.9) | 1.3 (0.5 to 3.4) |

| Birth weight, g | |||||

| <1500 | 454 | 15.6 (12.6 to 19.3) | 12.3 (9.6 to 15.7) | 1.8 (0.9 to 3.4) | 1.5 (0.8 to 3.2) |

| 1500–2499 | 6525 | 13.0 (12.2 to 13.8) | 10.0 (9.3 to 10.7) | 1.1 (8.6 to 13.7) | 1.9 (1.6 to 2.3) |

| 2500+ | 66 934 | 12.0 (11.8 to 12.3) | 9.0 (8.8 to 9.2) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) | 2.1 (2.0 to 2.3) |

| Birth length, cm | |||||

| <40 | 392 | 17.4 (13.9 to 21.4) | 14.0 (10.9 to 17.8) | 1.8 (0.9 to 3.6) | 1.5 (0.7 to 3.3) |

| 40–44.9 | 2693 | 12.7 (11.5 to 14.0) | 10.0 (9.0 to 11.2) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.5) | 1.6 (1.2 to 2.1) |

| 45–49.9 | 46 935 | 12.2 (11.9 to 12.5) | 9.1 (8.8 to 9.4) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) | 2.2 (2.1 to 2.3) |

| 50+ | 20 490 | 12.0 (11.5 to 12.4) | 9.1 (8.7 to 9.5) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) | 2.1 (1.9 to 2.3) |

| Head circumference at birth, cm | |||||

| <25 | 156 | 17.3 (12.2 to 24.0) | 14.7 (10.0 to 21.2) | 1.9 (0.7 to 5.5) | 0.6 (1.1 to 3.5) |

| 25–29.9 | 940 | 14.9 (12.8 to 17.3) | 11.2 (9.3 to 13.3) | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.4) | 2.3 (1.6 to 3.5) |

| 30–32.9 | 22 199 | 12.4 (12.0 to 12.9) | 9.2 (8.9 to 9.6) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 2.2 (2.0 to 2.4) |

| 33+ | 46 693 | 12.0 (11.7 to 12.3) | 9.1 (8.8 to 9.3) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) | 2.1 (2.0 to 2.2) |

Among 96 014 children aged up to 3 years with recorded information available regarding seizures, the prevalence rates of seizures, febrile seizures and afebrile seizure were 12.1% (95% CI 11.9% to 12.3%), 9.1% (95% CI 8.9% to 9.2%) and 0.9% (95% CI 0.9% to 1.0%), respectively. The prevalence rates of seizures, febrile seizures and afebrile seizures did not differ between children with sufficient and insufficient data regarding GA.

Risk factors for seizure among variables at birth

Tables 3 and 4 present the multiple logistic regression models used to identify risk factors for seizures and febrile seizures among the variables at birth in children born between 34 and 41 weeks’ GA. Sufficient information at birth (sex, GA, BW, BL and HC) was available for 68 693 children, and their data were used in the multiple logistic regression model analysis. Boys had an increased risk for seizures (OR: 1.15, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.20; ARI: 0.014, 95% CI 0.010 to 0.019) and febrile seizures (OR: 1.21, 95% CI 1.15 to 1.28; ARI: 0.016, 95% CI 0.012 to 0.020) compared with the girls.

Table 3.

Multiple logistic regression model for seizures occurring in children aged up to 3 years, born between 34 and 41 weeks of gestational age

| OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Sex, male | 1.15 (1.09 to 1.20) | <0.001 |

| Late preterm birth (34–36 weeks) | 1.05 (0.93 to 1.18) | 0.431 |

| Low birth weight (<2500 g) | 1.07 (0.97 to 1.17) | 0.201 |

| Birth length (<45 cm) | 1.02 (0.88 to 1.17) | 0.831 |

| Head circumference at birth (<30 cm) | 1.19 (0.94 to 1.49) | 0.156 |

Table 4.

Multiple logistic regression model for febrile seizures in children aged up to 3 years, born between 34 and 41 weeks of gestational age

| OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Sex, male | 1.21 (1.15 to 1.28) | <0.001 |

| Late preterm birth (34–36 weeks) | 1.10 (0.96 to 1.25) | 0.161 |

| Low birth weight (<2500 g) | 1.08 (0.97 to 1.20) | 0.182 |

| Birth length (<45 cm) | 1.03 (0.88 to 1.21) | 0.709 |

| Head circumference at birth (<30 cm) | 1.13 (0.86 to 1.46) | 0.373 |

Stratified analysis for risk of seizure

Table 5 presents the results of the analysis for the risk of seizures and febrile seizure in samples stratified by sex and BW. Boys born between 34 and 41 weeks’ GA with BW ≥2500 g exhibited an increased risk of seizures (OR: 1.14, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.20; ARI: 0.014, 95% CI 0.009 to 0.019; p<0.001) and febrile seizures (OR: 1.21, 95% CI 1.15 to 1.28; ARI: 0.016, 95% CI 0.011 to 0.020; p<0.001), when compared with girls with BW ≥2500 g. Boys born between 34 and 41 weeks’ GA with BW <2500 g had an increased risk of seizures (OR: 1.23, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.43; ARI: 0.024, 95% CI 0.007 to 0.041; p=0.006) and febrile seizures (OR: 1.33, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.57; ARI: 0.026, 95% CI 0.011 to 0.041; p=0.001) when compared with girls with BW <2500 g. Late preterm birth did not statistically increase the risk of seizures or febrile seizures in any of the four (stratified) groups.

Table 5.

Association between late preterm birth and the risk of seizure in children aged up to 3 years, born between 34 and 41 weeks of gestational age

| 34–41 weeks | 37–41 weeks (term) | 34–36 weeks (late preterm) | Term versus late preterm | |||||||

| n | Number of seizures | Incidence of seizure, % (95% CI) | n | Number of seizures | Incidence of seizure, % (95% CI) | n | Number of seizures | Incidence of seizure, % (95% CI) | P value | |

| Male with birth weight ≥2500 g | 34 354 | 4369 | 12.7 (12.4 to 13.1) | 33 411 | 4243 | 12.7 (12.4 to 13.1) | 943 | 126 | 13.4 (11.3 to 15.7) | 0.552 |

| Male with birth weight <2500 g | 2649 | 378 | 14.3 (13.0 to 15.7) | 1604 | 221 | 13.8 (12.2 to 15.6) | 1045 | 157 | 15.0 (13.0 to 17.3) | 0.394 |

| Female with birth weight ≥2500 g | 32 202 | 3642 | 11.3 (11.0 to 11.7) | 31 667 | 3578 | 11.3 (11.0 to 11.7) | 535 | 64 | 12.0 (9.5 to 15.0) | 0.63 |

| Female with birth weight <2500 g | 3483 | 414 | 11.9 (10.9 to 13.0) | 2454 | 291 | 11.9 (10.6 to 13.2) | 1029 | 123 | 12.0 (10.1 to 14.1) | 0.954 |

| n | Number of febrile seizures | Incidence of febrile seizure, % (95% CI) | n | Number of febrile seizures | Incidence of febrile seizure, % (95% CI) | n | Number of febrile seizures | Incidence of febrile seizure, % (95% CI) | P value | |

| Male with birth weight ≥2500 g | 34 354 | 3356 | 9.8 (9.5 to 10.1) | 33 411 | 3252 | 9.7 (9.4 to 10.1) | 943 | 104 | 11.0 (9.2 to 13.2) | 0.182 |

| Male with birth weight <2500 g | 2649 | 301 | 11.4 (10.2 to 12.6) | 1604 | 173 | 10.8 (9.4 to 12.4) | 1045 | 128 | 12.3 (10.4 to 14.4) | 0.26 |

| Female with birth weight ≥2500 g | 32 202 | 2636 | 8.2 (7.9 to 8.5) | 31 667 | 2591 | 8.2 (7.9 to 8.5) | 535 | 45 | 8.4 (6.4 to 11.1) | 0.812 |

| Female with birth weight <2500 g | 3483 | 306 | 8.8 (7.9 to 9.8) | 2454 | 211 | 8.6 (7.6 to 9.8) | 1029 | 95 | 9.2 (7.6 to 11.2) | 0.555 |

Discussion

This is the largest study reporting on the prevalence of seizures and febrile seizures in East Asia. Moreover, this population-based cohort study is the first to report the prevalence of seizures and febrile seizures in children aged up to 3 years according to GA. We also analysed the risk factors for seizures and febrile seizures and evaluated the association between late preterm birth and febrile seizures.

A cohort study conducted more than 30 years ago reported the prevalence rates of seizures and febrile seizures as 9.7% and 8.3%, respectively.7 However, subsequent studies have been scarce and a recent relatively smaller study reported the prevalence rate of febrile seizures as 12.3% (n=1560).21 By virtue of its large sample size, the 95% CI of the prevalence of febrile seizures was 8.9%–9.3% in this study, confirming the high prevalence rate of febrile seizures in Japan. The prevalence rates of febrile seizure vary geographically.2 6–11 15 22–26 The highest rate is in Guam, at 11.4% in children aged up to 5 years.24 The rate in South Korea is also high, at 11.2% in children aged up to 5 years.11 In contrast, the prevalence rate of febrile seizure is 2.3% in the UK,10 3.4% in the USA,6 4.3% in Turkey,15 4.9% in Denmark,22 6.9% in Finland25 and 10.1% in India.27 These geographical differences are attributed mainly to the racial and genetic factors.4 However, the prevalence rate of febrile seizures is only 0.4%–1.5% in China, as opposed to other East Asian countries.26

Differences may also be caused by variances in the study’s design. Prevalence rates reported by prospective studies are generally higher than those of retrospective studies, such as those using hospital-based surveys.25 The prevalence rates also differed among previous Japanese studies.28 A hospital-based Japanese survey estimated a 3.4% prevalence rate of febrile seizures in children aged up to 5 years.29 The lifetime prevalence of febrile seizure in Turkey also differed between studies (4.3% and 9.7%).15 23 Most previous large cohort studies were based on a database or datalink obtained from hospitals, according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code.2 8 11 22 26 Studies based on a datalink of ICD codes do not include children who experienced seizures or febrile seizures but did not visit the hospital. In contrast, our data were obtained directly from parents. Another strength of our study is the high coverage rate (>95%) of the Kobe city population, due to the unique physical examination system requirement for children aged 3 years. The response rate was around 70%–80% in most of the previous studies based on information obtained from patients or parents.9 15 24 Studies with high coverage rates of the target populations (n=1033, 1403) also had a relatively smaller population, compared with our study.25 27

We also determined the incidence rate of seizure and febrile seizure according to age. The peak age of seizure and febrile seizure onset was between 12 and 24 months, which is concurrent with the findings of earlier studies.2–4 Most febrile seizures occurred between 6 months and 3 years of age, with a peak incidence at 18 months, although approximately 6%–15% of cases occurred after the age of 4 years.4 Therefore, based on our results, the lifetime prevalence of febrile seizure is approximately 9.6%–10.7% in Japan. Our study did not investigate the associations between age and type of seizure or the genetic background. A previous ICD-10 coding study in Germany showed that the status epilepticus admission peaked at ages between 0 and 12 months.30 Especially, almost half of all super refractory status epilepticus admissions occurred between the ages of 0 and 12 months.30 A population-based genetic study in Scotland for children below the age of 36 months showed that children aged less than 6 months presenting with seizure had an increased chance of an underlying genetic cause compared with those between 24 and 36 months of age (OR: 4.9, 95% CI 1.9 to 12.8; p=0.004).31

Among the variables at birth, only male was found to be an independent risk factor for seizures and febrile seizures in this study. Boys had consistently more febrile seizures than girls, although only a few studies have identified statistical differences.7 8 10 11 15 27 The prevalence rates of seizures and febrile seizures tended to increase in children with late preterm births, low BW and low HC. However, our multivariate analysis identified no association between these variables and an increase in seizures or febrile seizures. We prepared another multiple logistic regression model with three variables: male, late preterm birth and low BW, after adjusting for the confounding bias among those variables. The results showed that only male was associated with an increased risk of seizures and febrile seizures (see online supplementary tables S1, S2). Moreover, stratified analysis by sex and BW did not reveal an increased risk of seizures or febrile seizures in children with late preterm births. In the past, the incidence rate of epilepsy clearly increased in children born prematurely and those with low BW.5 32 The incidence rate of epilepsy was 5.23 times higher in children born at 28–32 weeks’

bmjopen-2019-035977supp001.pdf (38.7KB, pdf)

GA than that in children born at 39–41 weeks’ GA.5 However, the incidence rate ratio declined to 1.86 and 1.20 in children born at 33–36 weeks’ GA and 37–38 weeks’ GA, respectively.5 Perinatal factors such as premature birth, low BW and brain injury at birth are also reported risk factors for a febrile seizure. However, the evidence is contradictory, which may partly be caused by the differences in the study’s design.3 4 8–11 17 33 It has also been reported that very preterm birth is associated with an increased risk of febrile seizures.17 These findings, along with our results, indicate that very preterm birth may increase the risk of seizures and febrile seizures; however, the risk is relatively small in children with late preterm births.

A unique feature of our large population-based cohort study is that we obtained information directly from parents using the examination system for 3-year-old children, which has a high population coverage rate (>95%). However, this design may also limit the accuracy of our diagnosis. Parents might have misrecognised seizures and febrile seizures. Recall bias may also be responsible; however, the effect is estimated to be small as seizures are worrisome and unforgettable events for most parents. In this study, definition for characterising seizures was not used by the health professionals when checking the information from questionnaires, which may decrease the accuracy of the seizures diagnosis. We were also unable to identify the lifetime prevalence of febrile seizures. Most previous studies included children aged up to 5 years10,11 22 24 25 27; however, our study only included children aged up to 3 years, similar to a few Japanese studies.7 21 Therefore, the lifetime prevalence of febrile seizures in Japan might be higher than that in our study. Finally, our study was limited by the lack of detailed clinical data on seizures or epilepsy syndromes. We could not determine the seizure duration. Therefore, we were unable to determine the prevalence of status epilepticus in the study population. Further studies are required to investigate the prevalence of status epilepticus, which requires emergency medical intervention and is associated with neurological sequelae.

Conclusion

We determined the prevalence of seizures and febrile seizures in children aged up to 3 years according to GA. Multiple logistic regression and stratified analyses revealed that late preterm birth was not associated with the risk of seizures or febrile seizures. We demonstrated that male is an independent risk factor for seizures and febrile seizures. Although very preterm birth may increase the risk of seizures and febrile seizures, the risk associated with late preterm birth is considerably small and less than that associated with male. Our findings indicate that concern for conditions such as seizures is unnecessary in late preterm birth babies, which will bring relief to their parents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Clinical and Translational Research Center at Kobe University Hospital for the statistical analysis of the data. We would also like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for the English language editing services.

Footnotes

Contributors: MN designed the project, participated in the data analysis and first drafted the manuscript. HM and HN designed and supervised the project and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. HY and HT supported in the data analysis and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. YI participated in the interpretation of results and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. KT participated in the data cleaning, supported in the data analysis and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. NN supported in the analysis and interpretation and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. KN participated in the data analysis and interpretation of results, and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. KI contributed to data analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the article and final approval of the version to be published. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This work was partly supported by Grants-in-Aid for Young Scientists of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (grant number: 18K15711) and the Kobe Public Health Research for Mothers and Children.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Approval was obtained from the review board of the Public Health Center of the city of Kobe (on 18 June 2018).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. Data are not publicly available. However, data may be obtained from the appropriate section in Kobe City on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Trinka E, Cock H, Hesdorffer D, et al. A definition and classification of status epilepticus-report of the ILAE task force on classification of status epilepticus. Epilepsia 2015;56:1515–23. 10.1111/epi.13121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sammon CJ, Charlton RA, Snowball J, et al. The incidence of childhood and adolescent seizures in the UK from 1999 to 2011: a retrospective cohort study using the clinical practice research Datalink. Vaccine 2015;33:7364–9. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.07.093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vestergaard M, Christensen J. Register-based studies on febrile seizures in Denmark. Brain Dev 2009;31:372–7. 10.1016/j.braindev.2008.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waruiru C, Appleton R. Febrile seizures: an update. Arch Dis Child 2004;89:751–6. 10.1136/adc.2003.028449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun Y, Vestergaard M, Pedersen CB, et al. Gestational age, birth weight, intrauterine growth, and the risk of epilepsy. Am J Epidemiol 2008;167:262–70. 10.1093/aje/kwm316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson KB, Ellenberg JH. Predictors of epilepsy in children who have experienced febrile seizures. N Engl J Med 1976;295:1029–33. 10.1056/NEJM197611042951901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsuboi T. Epidemiology of febrile and afebrile convulsions in children in Japan. Neurology 1984;34:175–81. 10.1212/WNL.34.2.175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vestergaard M, Wisborg K, Henriksen TB, et al. Prenatal exposure to cigarettes, alcohol, and coffee and the risk for febrile seizures. Pediatrics 2005;116:1089–94. 10.1542/peds.2004-2210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canpolat M, Per H, Gumus H, et al. Investigating the prevalence of febrile convulsion in Kayseri, Turkey: an assessment of the risk factors for recurrence of febrile convulsion and for development of epilepsy. Seizure 2018;55:36–47. 10.1016/j.seizure.2018.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verity CM, Butler NR, Golding J. Febrile convulsions in a national cohort followed up from birth. II-Medical history and intellectual ability at 5 years of age. BMJ 1985;290:1311–5. 10.1136/bmj.290.6478.1311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi YJ, Jung JY, Kim JH, et al. Febrile seizures: are they truly benign? longitudinal analysis of risk factors and future risk of afebrile epileptic seizure based on the national sample cohort in South Korea, 2002-2013. Seizure 2019;64:77–83. 10.1016/j.seizure.2018.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun Y, Vestergaard M, Christensen J, et al. Epilepsy and febrile seizures in children of treated and untreated subfertile couples. Hum Reprod 2007;22:215–20. 10.1093/humrep/del333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun Y, Vestergaard M, Christensen J, et al. Prenatal exposure to maternal infections and epilepsy in childhood: a population-based cohort study. Pediatrics 2008;121:e1100–7. 10.1542/peds.2007-2316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun Y, Strandberg-Larsen K, Vestergaard M, et al. Binge drinking during pregnancy and risk of seizures in childhood: a study based on the Danish national birth cohort. Am J Epidemiol 2009;169:313–22. 10.1093/aje/kwn334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ateşoğlu M, İnce T, Lüleci D, et al. Sociodemographic risk factors for febrile seizures: a school-based study from Izmir, Turkey. Seizure 2018;61:45–9. 10.1016/j.seizure.2018.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Douglass LM, Heeren TC, Stafstrom CE, et al. Cumulative incidence of seizures and epilepsy in ten-year-old children born before 28 weeks’ gestation. Pediatr Neurol 2017;73:13–19. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2017.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herrgård EA, Karvonen M, Luoma L, et al. Increased number of febrile seizures in children born very preterm: relation of neonatal, febrile and epileptic seizures and neurological dysfunction to seizure outcome at 16 years of age. Seizure 2006;15:590–7. 10.1016/j.seizure.2006.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engle WA, Tomashek KM, Wallman C, et al. Late-preterm infants: a population at risk. Pediatrics 2007;120:1390–401. 10.1542/peds.2007-2952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagasaka M, Morioka I, Yokota T, et al. Incidence of short stature at 3 years of age in late preterm infants: a population-based study. Arch Dis Child 2015;100:250–4. 10.1136/archdischild-2014-307045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maeyama K, Morioka I, Iwatani S, et al. Gestational age-dependency of height and body mass index trajectories during the first 3 years in Japanese small-for-gestational age children. Sci Rep 2016;6:38659. 10.1038/srep38659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimura M, Taketani T, Kurozawa Y. High incidence of status epilepticus and ongoing seizures on arrival to the hospital due to high prevalence of febrile seizures in IZUMO, Japan: a questionnaire-based study. Brain Dev 2019;41:848–53. 10.1016/j.braindev.2019.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vestergaard M, Obel C, Henriksen TB, et al. The Danish national hospital register is a valuable study base for epidemiologic research in febrile seizures. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59:61–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aydin A, Ergor A, Ozkan H. Effects of sociodemographic factors on febrile convulsion prevalence. Pediatr Int 2008;50:216–20. 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2008.02562.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stanhope JM, Brody JA, Brink E, et al. Convulsions among the Chamorro people of Guam, Mariana Islands. II. febrile convulsions. Am J Epidemiol 1972;95:299–304. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sillanpää M, Camfield P, Camfield C, et al. Incidence of febrile seizures in Finland: prospective population-based study. Pediatr Neurol 2008;38:391–4. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2008.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung B, Wat LCY, Wong V. Febrile seizures in southern Chinese children: incidence and recurrence. Pediatr Neurol 2006;34:121–6. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2005.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hackett R, Hackett L, Bhakta P. Febrile seizures in a South Indian district: incidence and associations. Dev Med Child Neurol 1997;39:380–4. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1997.tb07450.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sugai K. Current management of febrile seizures in Japan: an overview. Brain Dev 2010;32:64–70. 10.1016/j.braindev.2009.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohtahara S, Ishida S, Yamatogi Y, et al. Studies on febrile convulsions: 1. A neuroepidemiologic investigation of febrile convulsions in Tamano City, Okayama Prefecture. Jpn J Neurosci Res Assoc 1984;6:365–72. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schubert-Bast S, Zöllner JP, Ansorge S, et al. Burden and epidemiology of status epilepticus in infants, children, and adolescents: a population-based study on German health insurance data. Epilepsia 2019;60:911–20. 10.1111/epi.14729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Symonds JD, Zuberi SM, Stewart K, et al. Incidence and phenotypes of childhood-onset genetic epilepsies: a prospective population-based national cohort. Brain 2019;142:2303–18. 10.1093/brain/awz195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitehead E, Dodds L, Joseph KS, et al. Relation of pregnancy and neonatal factors to subsequent development of childhood epilepsy: a population-based cohort study. Pediatrics 2006;117:1298–306. 10.1542/peds.2005-1660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vestergaard M, Basso O, Henriksen TB, et al. Risk factors for febrile convulsions. Epidemiology 2002;13:282–7. 10.1097/00001648-200205000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-035977supp001.pdf (38.7KB, pdf)