Abstract

Objective

To assess the comparative efficacy of traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors in patients with acute gout.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources

Medline, Web of Science, China National Knowledge Infrastructure and Wanfang Data published as of 4 April 2020.

Methods

We performed meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of traditional non-selective NSAIDs versus cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors and RCTs of various cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors in patients with acute gout. The main outcome measures were mean change in pain Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) score and 5-point Likert scale score on days 2–8.

Results

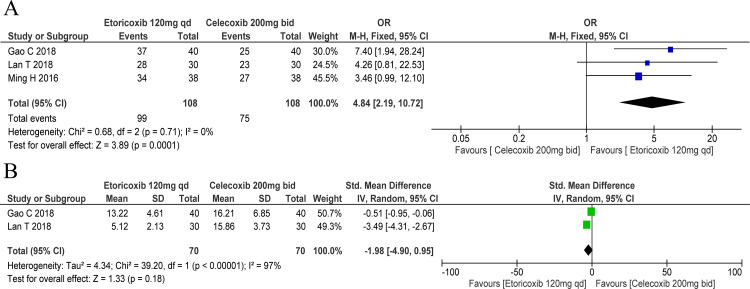

Twenty-four trials involving five drugs were evaluated. For pain Likert scale, etoricoxib was comparable to indomethacin (standardised mean difference (SMD): −0.09, 95% CI: −0.27 to 0.08) but better than diclofenac 50 mg three times a day (SMD: −0.53, 95% CI: −0.98 to 0.09). Regarding pain VAS score, etoricoxib was comparable to diclofenac 75 mg two times per day (SMD: −1.63, 95% CI: −4.60 to 1.34) and diclofenac 75 mg one time a day (SMD: −1.82, 95% CI: −5.18 to 1.53), while celecoxib was comparable to diclofenac 100 mg one time a day (SMD: −2.41, 95% CI: −5.91 to 1.09). Etoricoxib showed similar patients’ global assessment of response (SMD: −0.10, 95% CI: −0.27 to 0.07) and swollen joint count (SMD: −0.25, 95% CI: −0.74 to 0.24), but better investigator’s global assessment of response (SMD: −0.29, 95% CI: −0.46 to 0.11) compared with indomethacin. Etoricoxib showed more favourable pain VAS score than celecoxib (SMD: −2.36, 95% CI: −3.36 to 1.37), but was comparable to meloxicam (SMD: −4.02, 95% CI: −10.28 to 2.24). Etoricoxib showed more favourable pain Likert scale than meloxicam (SMD: −0.56, 95% CI: −1.10 to 0.02). Etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day was more likely to achieve clinical improvement than celecoxib 200 mg two times per day (OR: 4.84, 95% CI: 2.19 to 10.72).

Conclusion

Although cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors and traditional non-selective NSAIDs may be equally beneficial in terms of pain relief, cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors (especially etoricoxib) may confer a greater benefit.

Keywords: rheumatology, therapeutics, rheumatology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We evaluated data from randomised controlled trials that compared the efficacy of traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors in patients with acute gout.

A stringent search strategy was employed to minimise the influence of publication bias.

Most of the included studies were published in Chinese, although no language restriction was imposed during literature search.

Inclusion of relatively few trials, small sample size in the included trials and generally low quality are the main limitations.

Introduction

Gout is a chronic disease characterised by the deposition of monosodium urate crystals in various tissues as a result of elevated serum urate concentration.1 According to the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2010 study, the estimated global prevalence of gout is 0.08% and there is an increasing trend in the burden of gout.2 Worldwide, the reported prevalence of gout ranges from 0.1% to approximately 10%, and the incidence rates range from 0.3 to 6 cases per 1000 person-years.3 The prevalence and incidence of gout is highly variable across various regions of the world. In general, the prevalence of gout in developed countries is higher than that in developing countries.3 There is no national epidemiological data on the prevalence of gout in China; however, based on data from different regions at different time points, the estimated prevalence of gout in China is 1%–3%; in addition, the prevalence is steadily increasing every year.4

Acute gout typically begins with the involvement of a single joint in the lower limb (85%–90% of cases)—usually the first metatarsophalangeal joint.1 The management of acute gout includes rapid treatment of acute flares and long-term maintenance therapy.5–9 The main therapeutic options for an acute flare are colchicine, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and corticosteroids.5 The deposition of monosodium urate microcrystals in the articular and periarticular tissues elicits an acute or chronic inflammatory response, a condition referred to as gouty arthritis.1 10 11 There is evidence that monosodium urate microcrystals induce the production of cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2) in human monocytes.12 NSAIDs include traditional NSAIDs and selective COX-2 inhibitors—the former inhibits both COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes whereas the latter specifically antagonises COX-2. The efficacy of COX-2 inhibitors is comparable to that of traditional NSAIDs; however, COX-2 inhibitors have fewer adverse effects, particularly gastrointestinal adverse effects.13

In the past decade, NSAIDs have been emphasised as the first-line option for the management of acute gout, in accordance with the 2006 and 2016 European League Against Rheumatism recommendations5 8 and American College of Rheumatology guidelines.6 7 A meta-analysis found no significant difference between traditional NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors with regard to the pain score, inflammation score, change in patient’s global assessment from baseline and the health-related quality of life.13 Another meta-analysis indicated that the efficacy of etoricoxib in acute gout is similar to that of indomethacin and diclofenac; however, etoricoxib showed better performance than indomethacin in terms of the investigator’s global assessment of response to therapy and better analgesic efficacy in comparison to diclofenac.14 Two meta-analyses have assessed whether COX-2 inhibitors are more effective against acute gout than traditional NSAIDs.13 14 However, comparison between celecoxib and diclofenac15 was not included.

Given the increasing use of COX-2 inhibitors and the relatively large number of recent trials, evaluation of the comparative efficacy of various COX-2 inhibitors is a key imperative—both from the clinical and policy perspectives. After the withdrawal of rofecoxib, lumiracoxib and valdecoxib, three COX-2 inhibitors are currently used in clinical practice (etoricoxib, celecoxib and meloxicam). Meloxicam, an agent synthesised as a traditional NSAID, has a selective inhibitory effect against COX-2.16 In four studies, etoricoxib showed better efficacy than meloxicam17–20; in another four studies, etoricoxib showed better efficacy than celecoxib.21–24 Moreover, many studies published in Chinese were not included in previous meta-analyses. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis to provide an updated picture of the comparative clinical efficacy of traditional non-selective NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors, as well as that of the three COX-2 inhibitors in patients with acute gout.

Materials and methods

Literature strategy

Biomedical databases, including Medline (PubMed), Web of Science, Embase, China National Knowledge Infrastructure and Wanfang Data were searched for randomised controlled trials (RCTs; published as of April 2018) that investigated the comparative efficacy of traditional non-selective NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors or that of the three COX-2 inhibitors in patients with acute gout (online supplementary table S1). The key words used were: “selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors”, “COXIBs”, “etoricoxib”, “celecoxib”, “meloxicam”, “acute gout”, and “randomized controlled trials”. The reference lists of the studies, recent reviews, and meta-analyses retrieved were manually screened to identify additional studies. Two authors independently conducted the literature search; disagreements, if any, were resolved by consensus.

bmjopen-2019-036748supp001.pdf (405.5KB, pdf)

Selection criteria

We included RCTs into the meta-analysis if they qualified the following criteria. Study population: Adult patients (age ≥18 years) with a diagnosis of acute gout defined by the American Rheumatology Association diagnostic criteria.25 Study design: RCTs. Intervention: Trials that compared COX-2 inhibitors with traditional non-selective NSAIDs or compared the various COX-2 inhibitors. Comparison: Comparator treatments included one traditional non-selective NSAID or COX-2 inhibitor. Primary outcomes: Pain assessed using a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) score and 5-point Likert scale for days 2–8. Secondary outcomes were: (1) response rate (defined as the proportion of patients who achieved improvement in clinical symptoms) for days 2–8; (2) onset of efficacy (hours); (3) post-treatment serum C reactive protein level; (4) patient’s global assessment of response; (5) investigator’s global assessment of response and (6) inflammatory swelling. The exclusion criteria were the following: (1) trials that included a mix of people with acute gout and other causes of musculoskeletal pain, unless the results for the acute gout population could be separately analysed; (2) trials that investigated obsolete NSAIDs (eg, rofecoxib, lumiracoxib, valdecoxib) and (3) trials that compared between traditional non-selective NSAIDs.

Data collection

The titles and abstracts of articles retrieved on database search were independently screened by two authors to determine the eligibility of the articles according to predetermined selection criteria. The full texts of papers were obtained if more information was required to assess the eligibility for inclusion. Disagreements, if any, were resolved by consensus after review of the full-text article and with the involvement of a third author, if necessary.

Data pertaining to the following variables were independently extracted by two authors using a standardised data collection form: study design, patient characteristics, treatment details, duration of follow-up and relevant outcome measures. We extracted the raw data (mean and SD for continuous variables, and frequency of events or participants for dichotomous outcomes). Any differences in data extraction were resolved by referring to the original articles or by consulting a third reviewer author, if required.

Risk of bias assessment

Two authors assessed the risk of bias of the included studies using the methods recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration for the following items.26 We scored each study on six domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other sources of bias. The risk of bias was graded as high, low or unclear.

Furthermore, the quality of evidence across pooled studies (risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision and publication bias) was assessed by two researchers as per the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach and using the online version of GRADEpro GDT software (www.gradepro.org, McMaster University, 2016).27 28 Tables of summary of findings were created for every rated outcome in compliance to the Cochrane rules. Disagreements were resolved, first, by discussion and, then, by consulting a third senior author for arbitration.

Statistical analysis

Traditional meta-analyses were conducted for studies that directly compared COX-2 inhibitors and traditional non-selective NSAIDs and those that compared between etoricoxib, celecoxib and meloxicam. ORs and standardised mean difference (SMD) with corresponding 95% CIs were used for dichotomous and continuous outcomes, respectively. Heterogeneity was examined by using the Cochran’s Q-statistic; p-value <0.01 was considered significant. In addition, the I2 test was used to quantify heterogeneity (range, 0%–100%). P-value <0.01 for Q-test or I2 >50% indicated the existence of heterogeneity among the studies.29 In case of significant heterogeneity, the random effects model was used; in addition, subgroup analysis was conducted to identify the source of heterogeneity. The Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014) was used for the meta-analysis.

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient or public involvement as this was a database research study.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

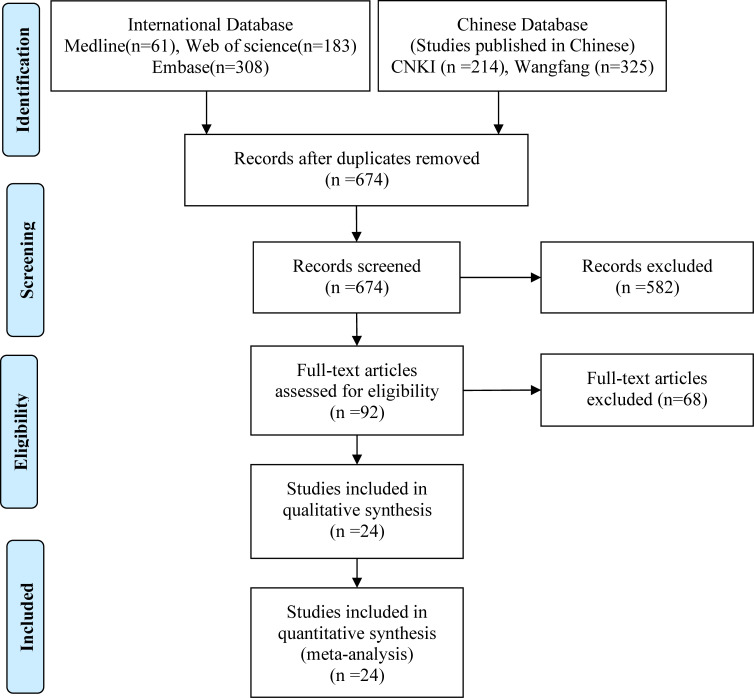

Of the 1091 articles retrieved on database search, 456 were excluded after a review of titles and abstracts or full-text articles owing to duplication (n=417) or irrelevant efficacy outcomes or measures (n=650) (figure 1). Finally, 24 trials involving five drugs and six treatment arms (etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day, indomethacin 50 mg three times a day, diclofenac 75 mg two times per day, diclofenac 100 mg one time a day, celecoxib 200 mg two times per day and meloxicam 15 mg one time a day), with a combined study population of 2513 patients, were included in the meta-analysis.15 17–24 30–44 Three studies were published in English30 31 34 and 21 in Chinese.15 17–24 32 33 35–44 The sample size of the included studies ranged from 12 to 140; three of these trials (12.5%) had less than 50 participants (table 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of literature search and study selection. CNKI, China National Knowledge Infrastructure.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the studies included in this meta-analysis

| Author | Year | Language | Treatment arms | n | Male | Age | Follow-up (days) |

| Schumacher et al30 | 2002 | English | Etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day | 75 | 73 | 48.5 (13.29) | 8 |

| Indomethacin 50 mg three times a day | 75 | 69 | 49.5 (13.71) | ||||

| Rubin et al31 | 2004 | English | Etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day | 103 | 98 | 51.1 (13) | 8 |

| Indomethacin 50 mg three times a day | 86 | 79 | 52.2 (12) | ||||

| Ye et al32 | 2010 | Chinese | Etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day | 40 | 33 | 45.12 (12.48) | 7 |

| Diclofenac 75 mg one time a day | 35 | 32 | 38.20 (15.51) | ||||

| Zhang et al20 | 2012 | Chinese | Etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day | 48 | 48 | 63.4 (12) | 8 |

| Meloxicam 15 mg one time a day | 36 | 36 | 64.1 (11) | ||||

| Gao and Pang33 | 2013 | Chinese | Etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day | 140 | 89 | 41.78 (12.57) | 7 |

| Diclofenac 75 mg two times per day | 140 | 92 | 42.48 (13.23) | ||||

| Hong and Xu21 | 2013 | Chinese | Etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day | 50 | 38 | 42.1 (9.8) | 7 |

| Celecoxib 200 mg three times a day | 50 | 40 | 41.5 (7.8) | ||||

| Li et al34 | 2013 | English | Etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day | 89 | 85 | 52 (15) | 5 |

| Indomethacin 75 mg two times per day | 89 | 81 | 53 (14) | ||||

| Guo et al18 | 2014 | Chinese | Etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day | 60 | 96 | 44.3 (15.6) | 8 |

| Meloxicam 15 mg one time a day | 60 | ||||||

| Guo et al35 | 2014 | Chinese | Etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day | 57 | 56 | 40.52 (11.27) | 5 |

| Diclofenac 75 mg one time a day | 56 | 54 | 43.03 (13.02) | ||||

| Lu36 | 2014 | Chinese | Etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day | 95 | 89 | 48.9 (2.3) | 7 |

| Diclofenac 50 mg three times a day | 51 | 49 | 46.7 (3.4) | ||||

| Kuang37 | 2015 | Chinese | Etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day | 40 | 29 | 42.8 (10.3) | 7 |

| Diclofenac 50 mg three times a day | 40 | 31 | 43.7 (11.2) | ||||

| Liu17 | 2015 | Chinese | Etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day | 32 | 21 | 45 (3.74) | 7 |

| Meloxicam 15 mg one time a day | 32 | 13 | 44 (3.53) | ||||

| Xia22 | 2015 | Chinese | Etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day | 40 | 27 | 50.17 (25.13) | 7 |

| Celecoxib 200 mg three times a day | 40 | 25 | 50.09 (25.34) | ||||

| Zhu38 | 2015 | Chinese | Etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day | 50 | 48 | 46.3 (6.9) | 7 |

| Diclofenac 50 mg three times a day | 50 | 49 | 46.5 (6.1) | ||||

| Cui and Liu15 | 2016 | Chinese | Diclofenac 100 mg one time a day | 12 | 11 | 41.5 (3.8) | 5 |

| Celecoxib 200 mg one time a day | 12 | 10 | 43.2 (4.2) | ||||

| Li et al39 | 2016 | Chinese | Etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day | 47 | 22 | 41.8 (11.3) | 5 |

| Diclofenac 75 mg one time a day | 47 | 21 | 40.5 (10.1) | ||||

| Ming24 | 2016 | Chinese | Etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day | 38 | 22 | 52.64 (12.28) | 7 |

| Celecoxib 200 mg two times per day | 38 | 23 | 52.79 (12.35) | ||||

| Pan and Chen40 | 2016 | Chinese | Etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day | 68 | 126 | 43.2 (13.6) | 7 |

| Diclofenac 50 mg three times a day | 68 | ||||||

| Zhou23 | 2016 | Chinese | Etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day | 28 | 16 | 53.37 (11.32) | 7 |

| Celecoxib 200 mg three times a day | 28 | 14 | 52.13 (10.13) | ||||

| Li et al19 | 2017 | Chinese | Etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day | 44 | 68 | 44.67 (14.99) | 8 |

| Meloxicam 15 mg one time a day | 44 | ||||||

| Gao and Yang41 | 2018 | Chinese | Celecoxib 200 mg two times per day | 40 | 29 | 58.4 (2. 8) | 7 |

| Etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day | 40 | 30 | 56.7 (2. 2) | ||||

| Lan et al42 | 2018 | Chinese | Celecoxib 200 mg two times per day | 30 | 24 | 52.21 (1.25) | 7 |

| Etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day | 30 | 25 | 52.26 (1.24) | ||||

| Sheng43 | 2019 | Chinese | Etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day | 42 | 82 | 39.17 (10.28) | 7 |

| Diclofenac 75 mg one time a day | 38 | ||||||

| Wu and Yang44 | 2019 | Chinese | Etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day | 30 | 23 | 45.98 (6.65) | 7 |

| Meloxicam 15 mg one time a day | 30 | 21 | 45.21 (7.20) |

Age presented as mean (SD).

Quality of included studies

Most of the included studies were rated as being of low quality. All studies15 17–24 32–34 36–40 published in Chinese had an unclear risk of allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, or selective reporting. Three studies showed no risk of bias30 31 34 and one study19 showed a high risk of random sequence generation (online supplementary figures S1 and S2).

The quality of evidence was rated as moderate in most comparisons. According to GRADE, the quality of evidence for comparison between traditional NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors was rated as high for pain on the 5-point Likert scale but moderate for pain on the VAS score (online supplementary table S2). However, the quality of evidence for comparison between the three COX-2 inhibitors was rated as moderate for the pain component of both the 5-point Likert scale and the VAS score (online supplementary table S3).

Comparative efficacy of traditional non-selective NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors

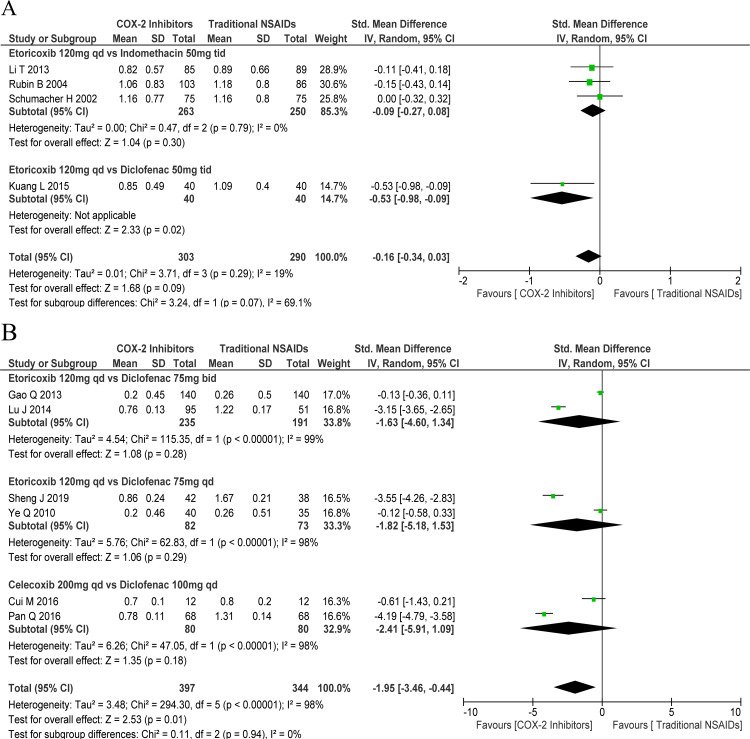

The efficacy of COX-2 inhibitors was comparable to that of the traditional NSAIDs in terms of the 5-point Likert scale (SMD: −0.15, 95% CI: −0.31 to 0.01) with mild heterogeneity (χ2=3.71, df=3, p=0.29, I2=19.0%; figure 1B). Subgroup analysis indicated comparable efficacy of etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day and indomethacin 50 mg three times a day (SMD: −0.09, 95% CI: −0.27 to 0.08) with mild heterogeneity (χ2=0.47, df=2, p=0.79, I2=0%). One study showed better efficacy of etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day versus diclofenac 50 mg three times a day (SMD: −0.53, 95% CI: −0.98 to –0.09; figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Forest plots of primary outcomes: cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors versus traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). (A) Pain Likert scale for days 2–8 and (B) pain Visual Analogue scale score) for days 2–8. bid, two times per day: qd, one time a day; tid, three times a day; vs, versus.

In general, COX-2 inhibitors exhibited better efficacy than traditional NSAIDs in terms of the pain VAS score (SMD: −1.95, 95% CI: −3.46 to –0.44), but with significant heterogeneity (χ2=294.30, df=5, p<0.001, I2=98.0%). However, on subgroup analysis, etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day showed similar efficacy as diclofenac 75 mg two times per day ((SMD: −1.63, 95% CI: −4.60 to 1.34) with significant heterogeneity (χ2=115.35, df=1, p<0.001, I2=99.0%)) and diclofenac 75 mg one time a day ((SMD: −1.82, 95% CI: −5.18 to 1.53) with significant heterogeneity (χ2=62.83, df=1, p<0.001, I2=98.0%)). Besides, celecoxib 200 mg two times per day showed comparable effect to that of diclofenac 100 mg one time a day (SMD: −2.41, 95% CI: −5.91 to 1.09) with significant heterogeneity (χ2=47.05, df=1, p<0.001, I2=98.0%) in regard to the pain VAS score (figure 2B).

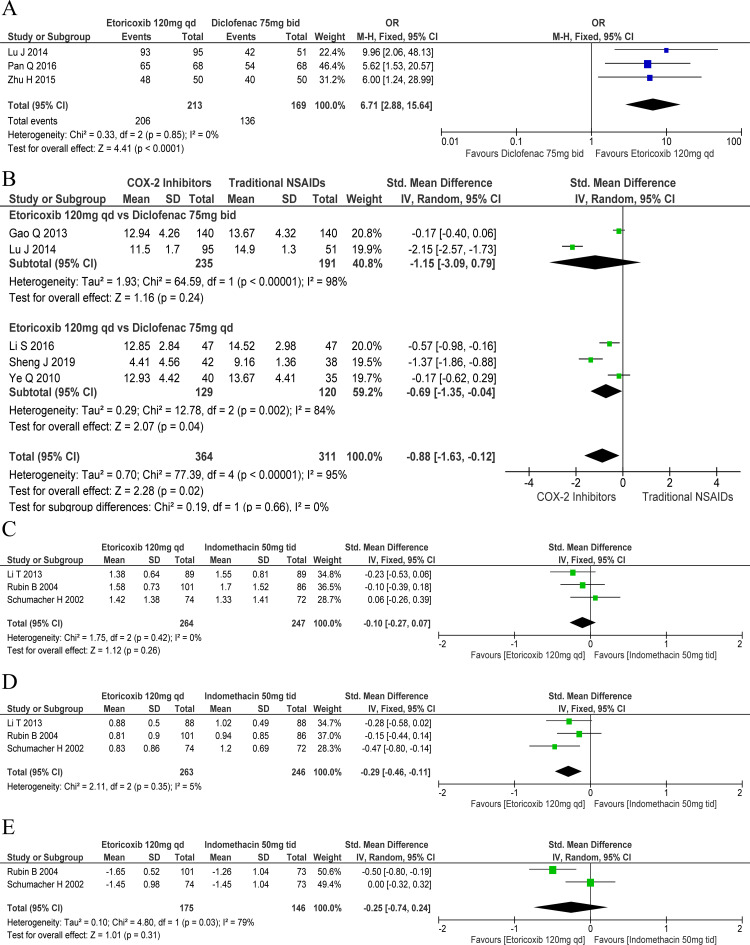

A significantly greater proportion of patients who received etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day (OR: 6.71, 95% CI: 2.88 to 15.64) showed clinical improvement, compared with those who received diclofenac 75 mg two times per day. There was mild heterogeneity among the included studies in this respect (χ2=0.33, df=2, p=0.85, I2=0%; figure 3A). However, the effect of etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day on C reactive protein was comparable to that of diclofenac 75 mg two times per day (SMD: −1.15, 95% CI: −3.09 to 0.79), but superior to that of diclofenac 75 mg one time a day (SMD: −0.69, 95% CI: −1.35 to –0.04) (figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Forest plots of secondary outcomes: cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors versus traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Response rate for (A) days 2–8, (B) C reactive protein, (C) patient’s global assessment, (D) investigator’s global assessment and (E) inflammatory swelling. bid, two times per day; qd, one time a day; tid, three times a day; vs, versus.

With regard to the global assessment of response in patients, the efficacy of etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day was comparable to that of indomethacin 50 mg three times a day (SMD: −0.10, 95% CI: −0.27 to 0.07) with mild heterogeneity (χ2=1.75, df=2, p=0.42, I2=0%; figure 3C). However, etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day showed better efficacy than indomethacin 50 mg three times a day in terms of the investigator’s global assessment of response (SMD: −0.29, 95% CI: −0.46 to –0.11) with mild heterogeneity (χ2=2.11, df=2, p=0.35, I2=5%; figure 3D). The effect of etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day on joint swelling was comparable to that of indomethacin 50 mg three times a day (SMD: −0.25, 95% CI: −0.74 to 0.24); there was marked heterogeneity among the studies included in the meta-analysis in this respect (χ2=4.80, df=1, p=0.03, I2=79%; figure 3E). Etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day had a shorter time to onset of therapeutic effect than diclofenac 75 mg one time a day (SMD: −0.94, 95% CI: −1.33 to –0.55).35

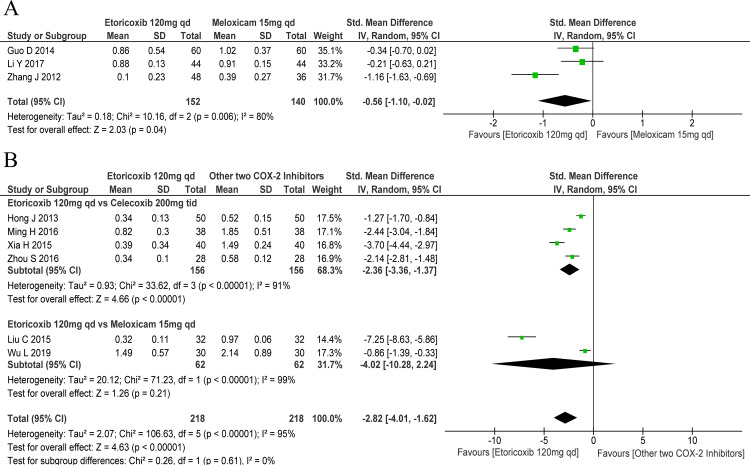

Comparative efficacy of COX-2 inhibitors

With regard to the pain Likert scale score, etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day was better than meloxicam 15 mg one time a day (SMD: −0.56, 95% CI: −1.10 to –0.02); there was marked heterogeneity among the included studies in this regard (χ2=10.16, df=2, p=0.006, I2=80%; figure 4A). In terms of the effect on the pain VAS score, etoricoxib was generally better than the other two COX-2 inhibitors (SMD: −2.82, 95% CI: −4.01 to –1.62); there was marked heterogeneity among the included studies in this respect (χ2=106.63, df=5, p<0.001, I2=95%). Subgroup analysis revealed better efficacy of etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day compared with celecoxib 200 mg three times a day (SMD: −2.36, 95% CI: −3.36 to –1.37), but comparable to meloxicam 15 mg one time a day (SMD: −4.02, 95% CI: −10.28 to 2.24; figure 4B). Moreover, the onset time for etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day was significantly shorter than that for meloxicam 15 mg one time a day (SMD: −1.57, 95% CI: −2.07 to –1.08).20

Figure 4.

Forest plots of primary outcomes: comparative efficacy of various cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors. (A) Pain Likert scale score for days 2–8 and (B) pain Visual Analogue Scale score for days 2–8. qd, one time a day; tid, three times a day; vs, versus.

Patients receiving etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day were more likely to achieve clinical improvement compared with those receiving celecoxib 200 mg two times per day (OR: 4.84, 95% CI: 2.19 to 10.72; figure 5A). Besides, a greater proportion of patients who received etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day (89.47%) experienced improvement in clinical symptoms compared with those who received celecoxib 200 mg two times per day (71.05%).24 However, etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day was comparable to celecoxib 200 mg two times per day in terms of C reactive protein (SMD: −1.98, 95% CI: −4.90 to 0.95; figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Forest plots of secondary outcomes: comparative efficacy of various cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors. Response rate for days 2–8 (A); C reactive protein (B). bid, two times a day; qd, one time a day.

Discussion

Main findings

In this meta-analysis, we evaluated the clinical outcomes of patients with acute gout who were treated with various NSAIDs. The results showed comparable performance of COX-2 inhibitors and traditional NSAIDs with regard to the effect on the pain Likert score and pain VAS scores; however, COX-2 inhibitors showed better efficacy than traditional NSAIDS with regard to several secondary outcomes, including the response rate and the investigator’s global assessment of response. Therefore, we were unable to conclude that COX-2 inhibitors clearly outperform the traditional NSAIDS. However, we found that etoricoxib 120 mg one time a day offers a clear advantage over celecoxib 200 mg three times a day in terms of pain VAS scores and clinical improvement, and over meloxicam in terms of pain Likert scale score.

We exclusively assessed evidence from available studies that compared the efficacy of currently used non-selective NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors in patients with acute gout. Our meta-analysis incorporated all the clinical outcomes of the available studies; however, most outcomes showed no difference, and several outcomes revealed that COX-2 inhibitors performed better. Therefore, there was no conclusive evidence of the comparative efficacy of non-selective NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors. However, our study revealed that etoricoxib may perform better in the management of patients with acute gout than either celecoxib or meloxicam. With regard to Likert scores, COX-2 inhibitors showed better efficacy than non-selective NSAIDs; however, on subgroup analysis, no significant difference were observed between the two groups of drugs. The inconsistency in the results between the pooled and subgroup analyses may be attributable to significant heterogeneity between the subgroups; we draw our conclusions based on the results of subgroup analyses.

Implication and strength

Our study has clinical implications. The prevalence of gout has increased in both developed and developing countries, presumably due to lifestyle changes.45 Of all the 291 conditions studied in the GBD 2010 study, gout ranked 138th in terms of disability, and 173rd in terms of overall burden.2 NSAIDs have gradually been established as the first-line therapeutic option for acute gout5 7 8; therefore, a comparison of the efficacy of NSAIDs is of much clinical relevance. Finally, we concluded that COX-2 inhibitors are comparable to traditional NSAIDs with regard to pain relief, but are preferable to traditional NSAIDs in terms of clinical symptoms and investigator’s global assessment of response. Etoricoxib may be the best option when COX-2 inhibitors are indicated.

Our study has considerable strengths. We designed the meta-analysis according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines and took meticulous care to minimise errors and ensure the validity of findings from all relevant studies. Our meta-analysis thoroughly addresses two key questions—that is, the comparative efficacy of traditional NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitor and the comparative efficacy of the three COX-2 inhibitors in terms of various clinical outcomes. Our findings may facilitate the selection of drugs for acute gout in clinical settings.

Safety

Several studies have revealed a better safety profile of COX-2 inhibitors compared with traditional non-selective NSAIDs in patients with acute gout13 14 or other pain conditions.46 Moreover, analysis of Vioxx gastrointestinal outcomes research (VIGOR) and two capsule endoscopy studies showed significantly less distal gastrointestinal blood loss with COX-2 inhibitors than with non-selective NSAIDs.47 The rates of upper gastrointestinal adverse clinical events were lower with etoricoxib than with diclofenac.48 When compared with traditional NSAIDs at standard dosages, treatment with celecoxib—at dosages greater than those indicated clinically—was associated with a lower incidence of symptomatic ulcers, ulcer-related complications, as well as other clinically important toxic effects.49 Gout and renal disorders are common comorbidities in elderly adults, leading to frequent administration of concomitant analgesics, especially NSAIDs. Several studies have shown that COX-2 inhibitors have a better or similar renal safety profile than ibuprofen or other traditional NSAIDs.50 51 It may be hypothesised that COX-2 inhibitors decrease the renal adverse effects relative to non-selective NSAIDs, as the kidney and vasculature express both COX-1 and COX-2. However, similar to traditional NSAIDs, due caution should be exercised while prescribing COX-2 inhibitors to patients with underlying renal diseases.52

The currently prevalent belief is that both traditional NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors are associated with an increased cardiovascular risk, with the probable exception of naproxen.53 However, the landmark PRECISION study seemingly refutes this widely held notion.54 55 In addition, there is no definitive evidence that COX-2 inhibitors pose a higher cardiovascular risk as compared with the traditional NSAIDs. The MEDAL study revealed similar rates of thrombotic cardiovascular events between long-term etoricoxib and diclofenac treatment in patients with arthritis.48 In addition to efficacy, care must be exercised to consider gastrointestinal, cardiovascular and renal conditions when choosing between NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors.

Colchine and naproxen

The study focuses on NSAIDs for acute flares. Colchicine and corticosteroids are also the main therapeutic options; however, owing to their different mechanisms of action and absence of direct comparative evidence, these drugs were not included in this meta-analysis. Several trials have compared traditional NSAIDS with oral corticosteroids (another recommended first-line options for acute flares); however, these trials did not qualify the inclusion criteria for this meta-analysis. Naproxen is a traditional NSAID that is used worldwide; however, it was not included in the meta-analysis due to the absence of trials comparing naproxen with COX-2 inhibitors. In a double-blind, randomised trial in patients with crystal-proven gout, naproxen was found to be as effective as prednisolone for acute flares.56 Similarly, a double-blind, parallel-group study revealed comparable efficacy of etodolac and naproxen in alleviating symptoms of acute gouty arthritis.57 Naproxen and phenylbutazone also showed comparable efficacy in the management of acute gout, with few and relatively mild adverse events.58

Limitations

Nevertheless, there are several limitations of our study. First, a relatively strict search strategy was used in the present study to achieve our objective; this limited the number of included RCTs. There are relatively few recent RCTs that investigated the effect of NSAIDs in acute gout. Moreover, most of these were published in Chinese. The relatively small number of studies and the small sample size in the studies included in the meta-analysis are the major limitations of our study. We did not evaluate publication bias using funnel plots because the number of studies was less than 10 for all outcome measures. Besides, most of the included studies published in Chinese were of low quality. Moreover, confounding factors such as the underlying disease and the use of other drugs may have affected the analysis. However, our review emphasises the potential importance of COX-2 inhibitors for acute gout. Given the clinical importance and acute nature of a gout flare, more trials focusing on clinically relevant outcomes are essential, especially in those patients who really need care.

Conclusion

Although COX-2 inhibitors and traditional non-selective NSAIDs may be equally beneficial in terms of pain relief, COX-2 inhibitors (especially etoricoxib) may confer a greater benefit.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Medjaden Bioscience for providing the editorial assistance. This assistance was funded by MSD China Holding Co.Ltd.

Footnotes

Contributors: ML, CY and XZ were responsible for the conception and design of the study. ML and CY did the analysis and interpreted the analysis. ML and CY wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and have approved the final version.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Dalbeth N, Merriman TR, Stamp LK. Gout. Lancet 2016;388:2039–52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00346-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith E, Hoy D, Cross M, et al. The global burden of gout: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1470–6. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuo CF, Grainge MJ, Zhang W, et al. Global epidemiology of gout: prevalence, incidence and risk factors. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2015;11:649–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeng XF, Chen YL. Chinese Society of rheumatology guideline for the management of gout. Zhejiang Medical Journal 2016;2017:1823–32. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richette P, Doherty M, Pascual E, et al. 2016 updated EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of gout. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:29–42. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khanna D, Fitzgerald JD, Khanna PP, et al. 2012 American College of rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64:1431–46. 10.1002/acr.21772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khanna D, Khanna PP, Fitzgerald JD, et al. 2012 American College of rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 2: therapy and antiinflammatory prophylaxis of acute gouty arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64:1447–61. 10.1002/acr.21773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T, et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part II: management. Report of a task force of the EULAR standing Committee for international clinical studies including therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:1312–24. 10.1136/ard.2006.055269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jordan KM, Cameron JS, Snaith M, et al. British Society for rheumatology and British health professionals in rheumatology guideline for the management of gout. Rheumatology 2007;46:1372–4. 10.1093/rheumatology/kem056a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richette P, Bardin T. Gout. Lancet 2010;375:318–28. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60883-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rott KT, Agudelo CA. Gout. JAMA 2003;289:2857–60. 10.1001/jama.289.21.2857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pouliot M, James MJ, McColl SR, et al. Monosodium urate microcrystals induce cyclooxygenase-2 in human monocytes. Blood 1998;91:1769–76. 10.1182/blood.V91.5.1769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Durme CMPG, Wechalekar MD, Buchbinder R, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for acute gout. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014:CD010120. 10.1002/14651858.CD010120.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang S, Zhang Y, Liu P, et al. Efficacy and safety of etoricoxib compared with NSAIDs in acute gout: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol 2016;35:151–8. 10.1007/s10067-015-2991-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cui MM, Liu ZL. The clinical effect of different analgesic anti – inflammatory solution in the treatment of acute gouty arthritis. Chin J of Clinical Rational Drug Use 2016;9:30–2. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noble S, Balfour JA. Meloxicam. Drugs 1996;51:424–30. 10.2165/00003495-199651030-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu CJ. Analysis of the efficacy and safety of etoricoxib and meloxicam in the treatment of acute gout. Medicine & people 2015:369–70. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo DB, YJ J, RP L, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of etoricoxib and meloxicam in treating acute gout. China Modern Medicine 2014:68–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y, Liu XR, Liang YQ, et al. Comparative clinical efficacy of etoricoxib and meloxicam in the treatment of acute gout. China Practical Medicine 2017;12:114–6. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang J, Ding J, HX W. Evaluation of efficacy and safety of etoricoxib and meloxicam in the treatment of patients with acute gout. Chin J Geriatr 2012;31:221–4. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong J, JY XU. Comparative efficacy of etoricoxib and celecoxib for the treatment of patients with acute gout. China Pharmaceuticals 2013;22:44–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xia HM. The efficacy and safety of etoricoxib and celecoxib in the treatment of acute gout. China & Foreign Medical Treatment 2015;34:156–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou SX. Comparative clinical efficacy and safety of etoricoxib and meloxicam in the treatment of acute gout. China Health Care & Nutrition 2016;26:264. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ming HY. Comparative clinical efficacy of etoricoxib and celecoxib in the treatment of acute gout. Journal of Northern Pharmacy 2016;13:49. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wallace SL, Robinson H, Masi AT, et al. Preliminary criteria for the classification of the acute arthritis of primary gout. Arthritis Rheum 1977;20:895–900. 10.1002/art.1780200320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higgins JE. Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Archiv für experimentelle Pathologie und Pharmakologie 2011;5:S38. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schünemann HJ, Mustafa R, Brozek J, et al. Grade guidelines: 16. grade evidence to decision frameworks for tests in clinical practice and public health. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;76:89–98. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moberg J, Oxman AD, Rosenbaum S, et al. The grade evidence to decision (ETD) framework for health system and public health decisions. Health Res Policy Syst 2018;16:45. 10.1186/s12961-018-0320-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higgins Jpt GS. Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Archiv für experimentelle Pathologie und Pharmakologie 2011;5:S38. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schumacher HR, Boice JA, Daikh DI, et al. Randomised double blind trial of etoricoxib and indometacin in treatment of acute gouty arthritis. BMJ 2002;324:1488–92. 10.1136/bmj.324.7352.1488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rubin BR, Burton R, Navarra S, et al. Efficacy and safety profile of treatment with etoricoxib 120 Mg once daily compared with indomethacin 50 Mg three times daily in acute gout: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:598–606. 10.1002/art.20007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ye Q, PF D, Wang ZZ, et al. Effect of etoricoxib on acute gout. Clinical Education of General Practice 2010:391–3. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao QL, Pang QJ. Evaluation of analgesic effect ofetoricoxib in the treatment of 140 patients with acute gout. China Pharmaceuticals 2013;22:33–4. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li T, Chen S-le, Dai Q, et al. Etoricoxib versus indometacin in the treatment of Chinese patients with acute gouty arthritis: a randomized double-blind trial. Chin Med J 2013;126:126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo M, Cheng ZF, YH H, et al. Evaluation of efficacy of COX-2 inhibitors in the treatment of patients with acute gouty arthritis. Progress in Modern Biomedicine 2014;14:5747–50. [Google Scholar]

- 36.JL L. Clinical efficacy of etoricoxib in the treatment of acute gouty arthritis. Practical Pharmacy And Clinical Remedies 2014:451–4. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuang L. Efficacy of etoricoxib in the treatment of acute gout. China Health Care & Nutrition 2015;25:247–8. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu HY. Clincal efficacy of etoricoxib in the treatment of 50 patients with acute gout. Medical Information 2015:380–1. [Google Scholar]

- 39.SJ L, Chen L, Chen Y, et al. Analysis of the clinical effect and safety of cyclooxygenase -2(COX-2)inhibitors of etoricoxib in treatment of acute gout arthritis. Jilin Medical Journal 2016;37:2447–8. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pan Q, Chen Q. Efficacy study of etoricoxib in the treatment of acute severe gouty arthritis. Guide of China Medicine 2016;14:107–8. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao CX, Yang Q. Comparative analysis of clinical effect and safety of celecoxib and etocoxib in the treatment of acute gout. Modern Medicine and Health Research 2018;2:47. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lan TZ, Fan FY, Yang W, et al. Comparison of the clinical efficacy and inflammatory changes of etocoxib and celecoxib in the treatment of acute gout. Medical Frontier 2018;8:102–3. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheng J. Clinical study on the improvement of inflammatory factor and pain in patients with actue gout with treatment of etoricoxib. Strait Pharmaceutical Journal 2019;31:93–5. [Google Scholar]

- 44.LL W, Yang YH. Analysis of effect of etocoxib and meloxicam in the treatment acute gouty arthritis. Health Guide 2019;11. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roddy E, Choi HK. Epidemiology of gout. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2014;40:155–75. 10.1016/j.rdc.2014.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roelofs PDDM, Deyo RA, Koes BW, et al. Non-Steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008:CD000396. 10.1002/14651858.CD000396.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strand V. Are COX-2 inhibitors preferable to non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in patients with risk of cardiovascular events taking low-dose aspirin? Lancet 2007;370:2138–51. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61909-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cannon CP, Curtis SP, FitzGerald GA, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes with etoricoxib and diclofenac in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis in the multinational etoricoxib and diclofenac arthritis long-term (medal) programme: a randomised comparison. Lancet 2006;368:1771–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69666-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silverstein FE, Faich G, Goldstein JL, et al. Gastrointestinal toxicity with celecoxib vs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: the class study: a randomized controlled trial. celecoxib long-term arthritis safety study. JAMA 2000;284:1247–55. 10.1001/jama.284.10.1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hegazy R, Alashhab M, Amin M. Cardiorenal effects of newer NSAIDs (celecoxib) versus classic NSAIDs (ibuprofen) in patients with arthritis. J Toxicol 2011;2011:1–8. 10.1155/2011/862153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Whelton A, Maurath CJ, Verburg KM, et al. Renal safety and tolerability of celecoxib, a novel cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor. Am J Ther 2000;7:159–74. 10.1097/00045391-200007030-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Giovanni G, Giovanni P. Do non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and COX-2 selective inhibitors have different renal effects? J Nephrol 2002;15:480–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Wandel S, et al. Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis. BMJ 2011;342:c7086. 10.1136/bmj.c7086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nissen SE, Yeomans ND, Solomon DH, et al. Cardiovascular safety of celecoxib, naproxen, or ibuprofen for arthritis. N Engl J Med 2016;375:2519–29. 10.1056/NEJMoa1611593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Solomon DH, Husni ME, Libby PA, et al. The risk of major NSAID toxicity with celecoxib, ibuprofen, or naproxen: a secondary analysis of the precision trial. Am J Med 2017;130:1415–22. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Janssens HJEM, Janssen M, van de Lisdonk EH, et al. Use of oral prednisolone or naproxen for the treatment of gout arthritis: a double-blind, randomised equivalence trial. Lancet 2008;371:1854–60. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60799-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maccagno A, Di Giorgio E, Romanowicz A. Effectiveness of etodolac ('Lodine') compared with naproxen in patients with acute gout. Curr Med Res Opin 1991;12:423–9. 10.1185/03007999109111513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sturge RA, Scott JT, Hamilton EB, et al. Multicentre trial of naproxen and phenylbutazone in acute gout. Ann Rheum Dis 1977;36:80–2. 10.1136/ard.36.1.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-036748supp001.pdf (405.5KB, pdf)