Abstract

Background

Prostate cancer is a common malignancy of the elderly, and with the aging of the population, the need is growing for therapies suitable for this age group. Lutetium‐177–prostate‐specific membrane antigen (Lu‐PSMA), a radiolabeled small molecule, binds with high affinity to prostate‐specific membrane antigen, enabling beta particle therapy targeted to metastatic castration‐resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). In a recent single‐arm phase II trial and a subsequent expansion cohort, a prostate‐specific antigen (PSA) decline of ≥50% was observed in approximately 60% of patients receiving Lu‐PSMA. Taking into account the specific challenges and potential toxicities of Lu‐PSMA administration in elderly men, we sought to retrospectively analyze the safety and activity of Lu‐PSMA in men aged older than 75 years with mCRPC.

Patients and Methods

The electronic medical records of 24 patients aged older than 75 years treated with Lu‐PSMA “off‐trial” were reviewed, and clinical data were extracted. Clinical endpoints were toxicity and activity, defined as a PSA decline ≥50%. Descriptive statistics were performed using Excel.

Results

The median age at treatment start was 81.7 years (range 75.1–91.9). The median number of previous treatment lines was four. The number of treatment cycles ranged from one to four; the mean administered radioactivity was 6 GBq per cycle. Treatment was generally tolerable; side effects included fatigue (n = 8, 33%), anemia (n = 7, 29%), thrombocytopenia (n = 5, 21%), and anorexia/nausea (n = 3, 13%). Clinical benefit was observed in 12 of 22 patients (54%); PSA decline above 50% was observed in 11 patients (48%) and was associated with significantly longer overall survival.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that Lu‐PSMA is safe and active in elderly patients with mCRPC.

Implications for Practice

Lutetium‐177–prostate‐specific membrane antigen (Lu‐PSMA), a radiolabeled small molecule, binds with high affinity to prostate‐specific membrane antigen, enabling beta particle therapy targeted to metastatic castration‐resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). The recently published single‐arm phase II trial with Lu‐PSMA, describing its safety and activity, did not include patients aged older than 75 years. In this study, Lu‐PSMA activity was retrospectively analyzed in patients aged older than 75 years and results indicate that treatment was tolerable and similarly active in this age group, with no new emerging safety signals. Despite the small cohort size, this analysis suggests that Lu‐PSMA can serve as an advanced palliative treatment line in mCRPC in elderly patients.

Keywords: Prostatic neoplasms, Lutetium, Theranostic nanomedicine, Aged

Short abstract

With the aging population, the need for therapies for prostate cancer in the elderly is growing. This article provides a retrospective analysis of the safety and activity of Lutetium‐177 prostate‐specific membrane antigen (Lu‐PSMA) in men older than 75 years treated at a single institution.

Introduction

Prostate cancer is a common disease, affecting middle‐aged (>50 years), elderly (>75 years), and extremely elderly (>85 years) men [1]. When the cancer is localized to the prostate, cure can very often be achieved using either radical surgery or radiation therapy, but metastatic disease mandates systemic therapy. Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is the cornerstone of treatment of metastatic disease, yet resistance to ADT inevitably occurs, rending the cancer “castration‐resistant” (i.e., castration‐resistant prostate cancer [CRPC]) [2].

Between 2010 and 2015, the armamentarium of active drugs against metastatic CRPC (mCRPC) significantly increased, as cabazitaxel, abiraterone, enzalutamide, and radium‐223 were added to docetaxel as life‐prolonging treatment options [3]. Notwithstanding these major advancements, leading to a significant increase in the median overall survival (OS) of mCRPC in the past 2 decades, mCRPC continues to be incurable, and thus the quest for more active approaches continues.

Cells of prostatic origin (including cancerous cells) express, in the vast majority of cases, a membrane‐bound protein called prostate‐specific membrane antigen (PSMA) at high concentrations [4]. This protein is encoded by the gene folate hydrolase 1 (FOLH1), also designated metallopeptidase glutamate carboxypeptidase II (GCPII) in the central nervous system (reviewed in [5]). Lutetium‐177–PSMA (Lu‐PSMA) is a radioisotope that binds with high affinity to PSMA and emits beta particles and can therefore damage PSMA‐expressing prostate cancers cells with relative sparing of adjacent cells [6]. This therapeutic approach is based on “theranostics”—the use of a radioactive compound for diagnostic imaging, target expression confirmation, and radionuclide therapy—and is currently given in a few countries across the world, among them Israel. Although a randomized phase III trial has not yet been performed, a single‐center single‐arm phase II study was recently published, showing a prostate‐specific antigen (PSA) decline of 50% or more in 17 (57%) of 30 patients (95% confidence interval 37–75) [7], but did not include patients aged older than 75 years. An expanded cohort of this trial, recently published, included elderly patients (aged older than 75 years) and showed a slightly higher PSA response rate of 64% [8].

Treatment of elderly men with Lu‐PSMA can be challenging for two main reasons. First, it necessitates self‐care for at least 72 hours after its administration because the patient is secluded from his family and caretakers throughout this time for safety reasons. Second, toxicities may differ or be more pronounced in aging men. Lu‐PSMA has been administered at the Sheba Medical Center (SMC) since the beginning of 2017 in an “off‐trial” self‐funded basis for men with mCRPC who have exhausted all approved lines of therapy or who were deemed ineligible for some of these lines. Here we provide a retrospective analysis of the safety and activity of Lu‐PSMA in men aged older than 75 years treated at SMC.

Subjects, Materials, and Methods

Patients

Patients were offered treatment with Lu‐PSMA if they had mCRPC and had exhausted all lines of approved treatment or were deemed ineligible for some of these lines according to their treating physician. Patients were informed that the treatment was not proven to prolong OS and was not reimbursed in Israel. As this was not a prospective clinical trial, there were no strict eligibility criteria in regard to performance status (PS) or blood tests, as long as the treating medical oncologist estimated that the potential benefit outweighed the potential harm. The patients were required to have PSMA‐positive metastatic cancer on PSMA positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) study within 6 months prior to treatment start according to their physician (based on the scan and other available clinical parameters). Gallium‐68–PSMA was quantified by calculating a maximum standardized uptake value, which was calculated by manually generating a region of interest over the sites of abnormally increased fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) activity. The finding in the prostatic gland was judged positive when focal PSMA uptake was higher than that of surrounding prostatic tissue [9]. A concurrent FDG‐PET/CT was not a prerequisite for receiving treatment. All patients signed an informed consent to treatment.

Lu‐PSMA Treatment

DKFZ‐PSMA‐617 precursor (ABX, Radeberg, Germany) was radiolabeled with Lutetium‐177 chloride ([177Lu]‐Cl3; Isotopia Molecular Imaging Ltd., Petah Tikva, Israel) in Isotopia's Radiopharmacy according to the manufacturer's instructions. Two hundred micrograms of the precursor was diluted with 700 μL of 0.4 M sodium acetate buffer pH 5.0 (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) containing 4 mg gentisic acid and added to 10 GBq of [177Lu]‐Cl3 in 0.04 mol/L HCl. The solution was heated to 100°C to 105°C for 45 minutes with intermittent gentle agitation. After cooling down of the reaction, the volume was adjusted to 5 mL using 0.9% sterile saline.

Radiochemical purity was established by high‐performance liquid chromatography.

Lu‐PSMA was administered by slow intravenous injection over 2 to 10 minutes. Patients were encouraged to be well hydrated by consuming oral fluids on the day of Lu‐PSMA administration. After the first cycle, quantitative single photon emission CT(qSPECT)/CT) scans were acquired at 4 and 24 hours from the vertex to the thighs enabling quantitation of Lu‐PSMA retention within tumor and normal tissues. For subsequent cycles, a single time point 24‐hour qSPECT/CT was acquired.

Clinical Assessment

Patients returned to clinic for safety assessment within 4 weeks after the first treatment cycle (unless clinical deterioration prevented it) and then according to physician's discretion. Complete blood tests including PSA were performed for each preplanned clinic visit and between visits upon need. Clinical benefit was subjectively assessed by the treating physician as an improvement in performance status, decrease in pain, decrease in narcotic consumption, or improvement in any cancer‐related symptom.

Subsequent Treatments

As the treatment was self‐funded, patients were not automatically offered additional treatments beyond the first cycle. The decision whether to continue treatment was based on the subjective clinical benefit, on the PSA decline, on toxicity and the recovery of the blood counts, and on patient's wish. Similarly, the timing of subsequent treatments varied, with a median of 2.1 months (range 1.3–8.4) between the first and second cycles and 3.7 months (range 1.9–5.7) between the second and third cycles. PSA nadir was defined as the lowest PSA value throughout Lu‐PSMA treatment.

Data Analysis

After the institutional review board's ethical approval, clinical data and laboratory results were extracted from the electronic medical record. When an exact date of an event in the remote past could not be extracted (such as date of biochemical failure or the appearance of castration resistance), the event was determined to occur on the 15th of the month if known, or the 15th of July if only the year was known. The date of mCRPC was determined as the first PSA rise after the PSA nadir achieved on ADT, as long as a second PSA increase subsequently occurred. Descriptive statistics were calculated with the Excel software (Microsoft, Redmond, WA), and overall survival was calculated using the Mantel‐Haenszel test. For comparison, toxicity and activity were also analyzed for 28 patients aged less than 75 years who received Lu‐PSMA at SMC during at the same time.

Results

The demographics of 24 patients aged older than 75 years who received Lu‐PSMA at SMC are given in Table 1. The median age at diagnosis of prostate cancer was 73.8 years, the median time to acquisition of castration resistance was 2.8 years, and the median time from the acquisition of CRPC to the first Lu‐PSMA treatment was 2.3 years. The median age at start of Lu‐PSMA was 81.7 years (range 75.1–91.9). One patient received Lu‐PSMA as his first line in the mCRPC setting, one patient received one prior line, four patients received two prior lines, and the rest (18, 69%) received three or more lines, with a median number of four prior treatment lines. The majority of patients received abiraterone, enzalutamide, docetaxel, and radium‐223 prior to the start of Lu‐223. The minority of patients received cabazitaxel. The percentage of patients treated with each line, and the relative responses, are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics | Median (range) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, years | 73.8 (60.9–88.8) |

| Gleason score at Dx | 8 (6–9) |

| Time from diagnosis to CRPC, years | 2.8 (0.7–17) |

| Time from CRPC to first lutetium treatment, years | 2.3 (0.9–6.2) |

| Age at first lutetium, years | 81.7 (75.1–91.9) |

| Number of treatment lines for mCRPC | 4 (0–5) |

| Previous treatment with abiraterone | 20 (83.3) |

| Response to abiraterone | 9 (45) |

| Previous treatment with enzalutamide | 20 (83.3) |

| Response to enzalutamide | 11 (55) |

| Previous treatment with docetaxel | 18 (75.0) |

| Response to docetaxel | 14 (77.8) |

| Previous treatment with cabazitaxel | 8 (33.3) |

| Response to cabazitaxel | 3 (37.5) |

| Previous treatment with radium‐223 | 14 (58.3) |

| Response to radium‐223 | 6 (42.9) |

Abbreviations: CRPC, castration‐resistant prostate cancer; Dx, diagnosis; mCRPC, metastatic CRPC.

The baseline clinical characteristics of patients before the start of Lu‐PSMA are given in Table 2. Approximately half of the patients had bone and lymph node metastasis, whereas approximately a quarter had metastasis only in bones, and another quarter had metastasis to visceral organs (either with or without bone or lymph node involvement). Almost half of the patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group PS of 3 or 4, and the majority of patients had pain, for which the vast majority required narcotic analgesics. The laboratory values (median and range) at treatment start are given in Table 2, demonstrating baseline anemia in general but preserved leukocyte and thrombocyte counts and a borderline albumin.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics at start of lutetium

| Characteristics | n (%) or median (range) |

|---|---|

| Metastatic sites | |

| Bone only | 5 (20.8) |

| Bone + lymph nodes | 13 (54.2) |

| Visceral (with or without bone/LNs) | 5 (25.0) |

| ECOG PS | |

| 0–1 | 7 (29.2) |

| 2 | 6 (25.0) |

| 3–4 | 11 (45.8) |

| Pain | |

| Yes | 14 (63.6) |

| No | 8 (36.4) |

| Requiring narcotics | |

| Yes | 12 (54.5) |

| No | 10 (45.5) |

| Hemogobin, d/dL | 10.7 (7.3–13.7) |

| WBC, K/μL | 6.2 (2.2–18.9) |

| PLTs, K/μL | 208 (17–382) |

| PSA, μg/L | 136 (1.5–1236) |

| LDH, IU/L | 367 (161–3989) |

| Alkaline phosphatase, IU/L | 151 (48–522) |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.5 (2.4–4.3) |

Abbreviations: ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; LN, lymph node; PLT, platelet; PSA, prostate‐specific antigen; WBC, white blood cell.

Treatment was generally tolerable. The most common side effect was fatigue, occurring in eight patients (33.3%), followed by anemia (n = 7, 29.2%), thrombopenia (n = 5, 20.8), anorexia/nausea (n = 3, 12.5%), and leukopenia in one patient. Fatigue was almost twice as prevalent in the elderly patients compared with the younger patient cohort. The frequency of anemia was also numerically higher in the elderly patients (Table 3). In one patient, prolonged deep thrombopenia after the second cycle (given on the background of baseline thrombopenia) precluded additional treatment cycles.

Table 3.

Toxicity in elderly (>75 years) and young (<75 years) patients

| Elderly (n = 24), n (%) | Young (n = 28), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | 8 (33.3) | 5 (17.9) |

| Anemia | 7 (29.2) | 6 (21.4) |

| Thrombopenia | 5 (20.8) | 6 (21.4) |

| Anorexia/nausea | 3 (12.5) | 0 (0) |

| Leukopenia | 1 (4.2) | 1 (3.6) |

| Elevated LFTs | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

Abbreviation: LFT, liver function test.

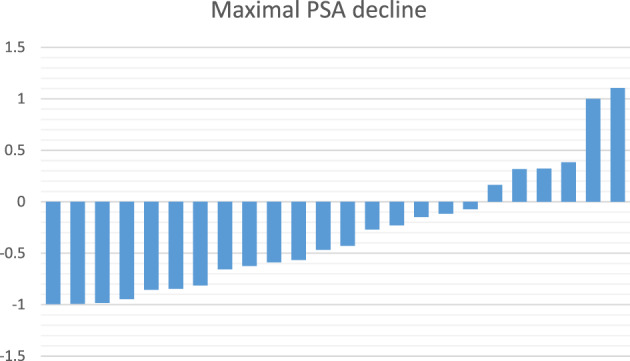

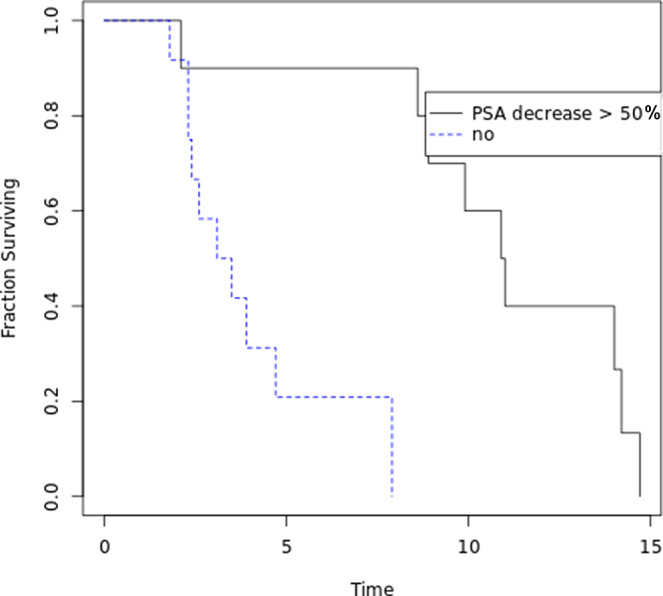

Of 22 patients with documentation, subjective clinical benefit was reported in 12 (54.5%). A PSA decline of 50% or more was seen in 11 patients (45.8%), and a PSA decline of 20% or more was seen in 15 patients (62.5%). The frequency of these three clinical outcomes was numerically higher in the elderly cohort than in the younger cohort, in a non–statistically significant manner (Table 4). The extent of PSA decline in individual patients is shown in Figure 1. In total, 18 patients (75%) had a PSA decline of any magnitude on treatment. At time of data analysis, five patients were still alive, of whom three were still on treatment. The median OS from treatment start was 4.7 months (range 1.7–14.7) for the entire cohort. A PSA decline of 50% or more was associated with a significantly higher median OS survival of 10.9 months versus 3.1 months (p = .0006; Fig. 2).

Table 4.

Response characteristics in elderly (>75 years) and young (<75 years) patients

| Elderly (n = 24), n (%) | Young (n = 28), n (%) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSA decrease >50% | 11 (45.8) | 7 (25) | .11 |

| No | 13 (51.2) | 21 (75) | |

| PSA decrease >20% | 15 (62.5) | 11 (39.3) | |

| No | 9 (37.5) | 17 (60.7) | .095 |

| Subjective clinical benefit | 12 (54.5) | 10 (38.5) | .26 |

| No | 10 (45.5) | 16 (61.5) |

Abbreviation: PSA, prostate‐specific antigen.

Figure 1.

Maximal PSA decrease on Lutetium‐177 treatment. Maximal PSA decrease was calculated as (nadir PSA − baseline PSA)/baseline PSA.Abbreviation: PSA, prostate‐specific antigen.

Figure 2.

Overall survival from first Lutetium treatment according to maximal PSA decrease. Kaplan‐Meier survival curves of patients who had a maximal PSA decrease of above or below 50%.Abbreviation: PSA, prostate‐specific antigen.

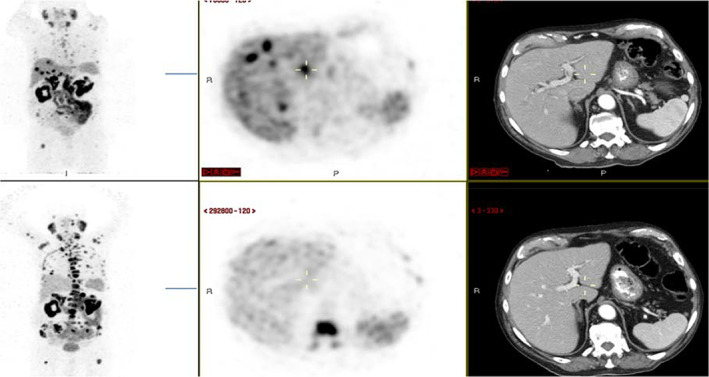

We present the case of the oldest patient in this cohort. He was diagnosed with localized prostate cancer, Gleason score of 9 (4 + 5), at the age of 86 years in 2012, and was started on ADT with significant PSA decline. In 2014 he developed castration resistance, underwent irradiation to the prostate and lymph nodes, and later—upon the development of metastatic disease to bone in 2015—received in sequence enzalutamide, radium‐223, and abiraterone. In December 2016 a PET‐PSMA revealed progressive disease in bone and a new uptake in the left adrenal (Fig. 3, lower panel). As he was deemed unfit for chemotherapy at the age of 88 years, he was started on Lu‐PSMA in February 2017, with a PSA decline from 777 to 105, with subjective clinical benefit and side effects of fatigue, dry mouth, and a rash. He received his second Lu‐PSMA treatment in April 2017, after a slight PSA increase to 177. His PSA further decreased to 44 by August 2017. Repeat PET‐PSMA showed a significant improvement in the size of the left adrenal metastasis and significant decrease in bone uptake, with the appearance of new liver metastasis (Fig. 3, upper panel). In October 2017, upon a PSA increase to 805, he received a third treatment with Lu‐PSMA that led to a transient PSA decrease to 177 in November, followed by a rapid increase to 720 in December 2017. He was therefore not offered a fourth course and succumbed to his disease in January 2018, at the age of 92, 11 months after initiation of treatment.

Figure 3.

Positron emission tomography (PET)–prostate‐specific membrane antigen (PSMA) and computed tomography (CT) scans of a patient before (lower panel) and after (upper panel) two cycles Lutetium‐177–PSMA. Left, coronal view, PET‐PSMA; middle, sagittal view, PET‐PSMA; right, sagittal view, CT scan.

Discussion

Theranostics—namely, the administration of a therapeutic dose of radiation by targeting specific biological pathways—is emerging as a new therapeutic modality in oncology. Lutetium‐177‐dotatate has already been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of neuroendocrine tumors, and Lutetium‐177–PSMA is already in use in several countries across the world, albeit in most of them in an “off‐trial” nonapproved setting. In the absence of data from a randomized phase III trial, the strongest evidence for the activity of Lu‐PSMA emerged from a single‐arm single‐center phase II trial [7], but this trial did not accrue patients aged older than 75 years. Our current retrospective analysis addresses this gap by analyzing the toxicity and activity of Lu‐PSMA in patients aged older than 75 years.

All patients in this cohort have had prostate cancer for several years prior start of Lu‐PSMA and have been heavily pretreated, mostly with new‐generation hormonal agents (abiraterone, enzalutamide) but also with docetaxel and, to a lesser extent, radium‐223 and cabazitaxel. Most patients had pain at baseline and a compromised performance status. This represents the “real‐life” clinical characteristics of patients currently receiving Lu‐PSMA in our center and suggests that our observations regarding toxicity and activity indeed represent the real‐life setting.

Our results show that there were no new safely signals in elderly patients; side effects were similar to the side effects reported by Hofman et al. [7] and Violet et al. [8] and to the side effects appearing in our “young” cohort. Fatigue and anemia were numerically more frequent in the elderly versus young cohort. These observations warrant further assessment in a prospective trial, as fatigue may become debilitating in older patients, and anemia may negatively affect cardiac and respiratory function, both which are often compromised in the elderly population.

A little more than half of the patients reported subjective clinical benefit on treatment, manifesting as improvement in pain and/or function or reduction in other disease‐related symptoms (such as fatigue, anorexia, or general malaise). Nearly half (45.5%) of the patients had a maximal PSA decrease of above 50% from baseline that was associated with significantly prolonged survival compared with those who did not have such a PSA decline. This observation is in keeping with the results from the prospective trial by Hofman et al. [7] and may suggest that biochemical response translates to an OS benefit. Indeed, in the current absence of evidence for an OS benefit of Lu‐PSMA, it is our current practice to continue treatment in patients with a PSA decline on treatment or with clear clinical benefit, preferably both.

Our chart review has several clear limitations. First, it includes a small number of patients with heterogenous disease characteristics and prior treatments. Second, toxicities occurring in a small minority of patients may not have been captured, especially as the charts were reviewed retrospectively. Last, it cannot prove or disprove the ability of Lu‐PSMA to prolong overall survival, nor can it be used to compare this treatment with other available treatments in this age group. With these limitations in mind, our review does provide evidence that Lu‐PSMA administration is generally tolerable irrespective of age, thus providing the practicing oncologist evidence‐based knowledge regarding its feasibility in elderly patients with mCRPC.

Conclusion

Our results show that administration of Lu‐PSMA in patients aged older than 75 years is similar to its administration in younger patients in terms of both toxicity and activity. Because Lu‐PSMA is a generally very well‐tolerated treatment, we think that it provides a good therapeutic option in this age group. Prospective clinical trials, currently in execution, will further elucidate the role of Lu‐PSMA in the treatment continuum of patients of all ages with mCRPC.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Raya Leibowitz, Tima Davidson, Moran Gadot, Margalit Aharon, Raanan Berger

Provision of study material or patients: Tima Davidson, Moran Gadot, Margalit Aharon, Avraham Malki, Meital Levartovsky, Cecilie Oedegaard, Akram Saad, Israel Sandler, Simona Ben‐Haim, Liran Domachevsky

Collection and/or assembly of data: Tima Davidson, Moran Gadot, Margalit Aharon, Avraham Malki, Meital Levartovsky, Cecilie Oedegaard, Akram Saad, Israel Sandler, Simona Ben‐Haim, Liran Domachevsky

Data analysis and interpretation: Raya Leibowitz, Moran Gadot, Raanan Berger

Manuscript writing: Raya Leibowitz, Tima Davidson

Final approval of manuscript: Raya Leibowitz, Tima Davidson, Moran Gadot, Margalit Aharon, Avraham Malki, Meital Levartovsky, Cecilie Oedegaard, Akram Saad, Israel Sandler, Simona Ben‐Haim, Liran Domachevsky, Raanan Berger

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

Disclosures of potential conflicts of interest may be found at the end of this article.

No part of this article may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form or for any means without the prior permission in writing from the copyright holder. For information on purchasing reprints contact Commercialreprints@wiley.com. For permission information contact permissions@wiley.com.

References

- 1.Cancer stat facts: Prostate cancer. National Cancer Institute Web site. Available at https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html. Accessed December 31, 2019.

- 2. Leibowitz‐Amit R, Joshua A. Targeting the androgen receptor in the management of castrationresistant prostate cancer: Rationale, progress, and future directions. Curr Oncol 2012;19(suppl 3):S22–S31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Crawford ED, Petrylak D, Sartor O. Navigating the evolving therapeutic landscape in advanced prostate cancer. Urol Oncol Semin Orig Investig 2017;35:S1–S13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chang SS. Overview of prostate‐specific membrane antigen. Rev Urol. 2004;6(suppl 10):S13–S18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vornov JJ, Peters D, Nedelcovych M et al. Looking for drugs in all the wrong places: Use of GCPII inhibitors outside the brain. Neurochem Res 2019. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Emmett L, Willowson K, Violet J et al. Lutetium 177PSMA radionuclide therapy for men with prostate cancer: A review of the current literature and discussion of practical aspects of therapy. J Med Radiat Sci 2017;64:52–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hofman MS, Violet J, Hicks RJ et al. [177Lu]‐PSMA‐617 radionuclide treatment in patients with metastatic castration‐resistant prostate cancer (LuPSMA trial): A single‐centre, single‐arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:825–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Violet J, Sandhu S, Iravani A et al. Long term follow‐up and outcomes of re‐treatment in an expanded 50 patient single‐center phase II prospective trial of Lutetium‐177 (177Lu) PSMA‐617 theranostics in metastatic castrate‐resistant prostate cancer. J Nucl Med 2019. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Onal C, Torun N, Oymak E et. Retrospective correlation of 68Ga‐PSMA uptake with clinical parameters in prostate cancer patients undergoing definitive radiotherapy. Ann Nucl Med 2020. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]