Abstract

Background

After 5 years of annual follow‐up following breast cancer, Dutch guidelines are age based: annual follow‐up for women <60 years, 60–75 years biennial, and none for >75 years. We determined how the risk of recurrence corresponds to these consensus‐based recommendations and to the risk of primary breast cancer in the general screening population.

Subjects, Materials, and Methods

Women with early‐stage breast cancer in 2003/2005 were selected from the Netherlands Cancer Registry (n = 18,568). Cumulative incidence functions were estimated for follow‐up years 5–10 for locoregional recurrences (LRRs) and second primary tumors (SPs). Risks were compared with the screening population without history of breast cancer. Alternative cutoffs for age were determined by log‐rank tests.

Results

The cumulative risk for LRR/SP was lower in women <60 years (5.9%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 5.3–6.6) who are under annual follow‐up than for women 60–75 (6.3%, 95% CI 5.6–7.1) receiving biennial visits. All risks were higher than the 5‐year risk of a primary tumor in the screening population (ranging from 1.4% to 1.9%). Age cutoffs <50, 50–69, and > 69 revealed better risk differentiation and would provide more risk‐based schedules. Still, other factors, including systemic treatments, had an even greater impact on recurrence risks.

Conclusion

The current consensus‐based recommendations use suboptimal age cutoffs. The proposed alternative cutoffs will lead to a more balanced risk‐based follow‐up and thereby more efficient allocation of resources. However, more factors should be taken into account for truly individualizing follow‐up based on risk for recurrence.

Implications for Practice

The current age‐based recommendations for breast cancer follow‐up after 5 years are suboptimal and do not reflect the actual risk of recurrent disease. This results in situations in which women with higher risks actually receive less follow‐up than those with a lower risk of recurrence. Alternative cutoffs could be a start toward risk‐based follow‐up and thereby more efficient allocation of resources. However, age, or any single risk factor, is not able to capture the risk differences and therefore is not sufficient for determining follow‐up. More risk factors should be taken into account for truly individualizing follow‐up based on the risk for recurrence.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Risk‐based follow‐up, Locoregional recurrence, Second primary, Thresholds

Short abstract

Actual survival benefits related to the intensive follow‐up recommendations of current guidelines for patients with breast cancer are unclear. This article analyses long‐term breast cancer recurrence patterns to determine how the current age‐based recommendations on follow‐up schedules after 5 years correspond to the actual risk of locoregional recurrence and second primary breast cancer. Alternative guidelines are proposed.

Introduction

Early detection and improved treatment have substantially decreased breast cancer–related mortality, yet the resulting increase in the need for follow‐up care has an impact on health care resources [1]. In the first year of follow‐up, the focus is on psychosocial complaints, monitoring quality of life and side effects [1]. After the first year, the main goal of follow‐up is early detection of locoregional recurrences (LRRs) and second primary breast cancer (SP). Detection of asymptomatic distant metastasis (DM) is not part of routine follow‐up [2, 3], as early detection of DM currently has no proven impact on survival [4]. Despite the current intensive follow‐up, its actual survival benefit is unclear, with only 34% of the LRRs being detected asymptomatically during regular follow‐up visits [5]. Approximately 40%–50% of the recurrences are detected by women themselves between regularly scheduled follow‐up visits [4]. Follow‐up visits are also a burden to patients, as they induce anxiety and stress [6, 7]. Additionally, there is disutility linked to false‐positive tests and subsequent invasive biopsies, as well as costs. Moreover, the current follow‐up is uniform for all patients and not based on the individual risk of recurrence. Previous studies revealed that risk of recurrence within the 5‐year follow‐up period is dependent on patient‐, tumor‐, and treatment‐related characteristics and changes over time [8]. One of these characteristics is age; especially young women are at increased risk of recurrence [8, 9, 10]

The current follow‐up in The Netherlands consists of annual follow‐up visits in the hospital for a minimum of 5 years, with clinical examination and mammography [3]. This is comparable to follow‐up schedules in other countries, such as the U.K. [11], Australia [12] and the U.S. [13]. Dutch recommendations on the monitoring after 5 years of follow‐up are based on consensus. The age after 5 years of follow‐up determines the schedule: women <60 years will continue with annual visits and those between the ages of 60 and 75 biennial visits (in the population‐based screening program), whereas for those >75 years, the guideline suggests to consider stopping follow‐up. With these age‐based recommendations, implicit assumptions are made as to what level of risk is appropriate for which frequency of follow‐up visits. It is uncertain whether the recommendations capture the differences of developing an LRR or SP between the age groups after 5 years. Ideally, risk groups should clearly differentiate in risk and the frequency of follow‐up visits should match the risk of recurrence, with higher‐risk patients receiving more follow‐up visits, unless the abovementioned lack of value of follow‐up becomes translated into practice.

Women without a history of breast cancer aged 50–75 years are invited by the national breast cancer screening program to undergo biennial screening. It is unclear how the risk for primary breast cancer in the healthy screening population and the corresponding recommendations relate to women with a history of breast cancer who are at risk for recurrence and are advised annual, biennial, or no hospital follow‐up. When examining the patterns in the risk of recurrence, risk thresholds could be identified and support evidence‐based follow‐up decisions.

Therefore, the aims of this study were to analyze long‐term breast cancer recurrence patterns and determine how the current age‐based recommendations on the follow‐up schedules after 5 years correspond to the actual risk of LRR and SP. Moreover, alternative age cutoffs are proposed, and risk of LRR or SP was compared with the risk of breast cancer in the general screening population aged 50–74 years.

Subjects, Materials, and Methods

Data

Women were selected from the nationwide population‐based database of the Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR). Based on pathological notification through the Pathology Automated Archives system, trained registration clerks gathered data concerning patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics directly from patients' files. Information on 10 years of follow‐up was gathered in retrospect from the patient files.

Women diagnosed with primary invasive breast cancer in 2003 or 2005 without DM or previous malignant, in situ, or synchronous tumors who were curatively treated by means of surgery and of whom complete 10‐year follow‐up was available were selected from the NCR. Women with macroscopic residue after surgery or microscopic residue without adjuvant treatment, those with tumor stage pT4, or those treated outside The Netherlands were excluded. This led to the inclusion of 18,568 women. Vital status was obtained through linkage with the municipality registry and complete until February 2016. Missing data were multiple imputed based on the chained equation method [14, 15]. The imputation model consisted of all variables used in the analysis. Thirty data sets were generated, and the estimates and standard errors were pooled using Rubin's rules [16]. For comparison, the analysis was performed using both the imputed data set and the data set that contained only the complete cases. Also, the convergence of the imputations was checked graphically.

The primary endpoint in this study was diagnosis of either LRR or SP during 10 years of follow‐up, whichever came first. Recurrent disease in the ipsilateral breast, chest wall, ipsilateral axillary, or supraclavicular, infraclavicular, or internal mammary lymph nodes was registered as LRR in the NCR [17]. Any epithelial breast cancer with or without lymph node metastasis in the contralateral breast was registered as an SP [17]. The date of last surgery was considered the starting point of the follow‐up.

Comparison of Risk in Current Age Groups, Screening Population, and Alternative Age Groups

With competing‐risks regression, the cumulative incidence functions for the first LRR, SP, and LRR/SP together were estimated with maximum likelihood according to the method of Fine and Gray [18]. Patients developing synchronous (within 3 months) LRR and DM or SP and DM were registered as having DM. DM was used as competing event for the analyses with both LRR and SP as endpoint, both DM and SP for the analysis with LRR as endpoint, and both DM and LRR where SP was endpoint. Furthermore, DM served as a proxy for breast cancer–related death [19], as more than 80% of the patients with DM after the primary tumor died within 10 years. The selection of explaining variables besides age during 10 years of follow‐up was based on literature [20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30] and consisted of characteristics of the primary tumor: histology (ductal, lobular, mixed, or other), primary tumor grade (Bloom Richardson grade I, II, III), size (pT1–3), multifocality (no, yes), lymph nodes status (pN0–3), estrogen receptor (ER) status (negative, positive), progesterone receptor (PR) status (negative, positive), human epidermal growth receptor 2 (HER2/neu) status (negative, positive), type of surgery (lumpectomy, mastectomy), axillary lymph node dissection (no, yes), chemotherapy (no, yes), radiation therapy (no, yes), and endocrine therapy (no, yes). Correlation between variables was assessed using a correlation matrix. The variables PR and ER receptor status showed a high correlation and were combined into hormone receptor status as a single variable [31].

The cause‐specific hazard functions after 5 years of follow‐up for LRR or SP within the current age groups were determined for the three age groups that are distinguished in the guideline (<60, 60–74, >74 after 5 years of follow‐up). The difference in risk was assessed by comparing the cumulative risks as well as the subhazard ratios (sHRs) from the multivariable analysis. Also, the cumulative incidence functions of the three current age groups for the follow‐up years 5–10 were compared with the 5‐year incidence of primary breast cancer in the screening population divided in 5‐year age groups. To determine the 5‐year risk of primary breast cancer in the population that is invited for the biennial screening program (50–75 years), data from the incidence years 2005–2009 from the NCR were used, as were mortality data from Statistics Netherlands [32]. The life table method was used to calculate this risk with adjustments for mortality from other causes and the prevalence of cancer in the population.

By testing the survivor functions (events predicted vs. observed) of both LRR and SP per 5‐year age intervals using the log‐rank test, alternative cutoffs for age were determined to obtain a greater differentiation in risk between the groups. The difference in risk between the current age groups and when using the new age cutoffs was compared graphically and by the sHRs obtained with competing risks regression, corrected for other explaining variables.

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Of the 18,568 patients, 65% were within primary breast cancer screening age (50–75 years) after 5 years of follow‐up. During the 10 years of follow‐up, 852 (4.6%) developed an LRR, 868 (4.7%) an SP, and 2,484 (13.4%) a DM as first event. The median follow‐up time for the total population was 9.6 years (interquartile range [IQR] 9.0–10.0). For patients with an LRR as a first event, the median disease‐free interval (DFI) was 3.7 years (IQR 1.8–6.5). Median DFI before an SP was slightly longer at 4.8 years (IQR 2.3–7.1). Table 1 summarizes the patients, tumor, and treatment characteristics stratified by first event.

Table 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics, stratified by event type occurring within 10 years after treatment

| Characteristics | LRR (n = 852) | SP (n = 868) | Total (n = 18,568) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Age, years | ||||||

| <40 | 81 | 9.5 | 44 | 5.1 | 1,121 | 6.0 |

| 40–49 | 178 | 20.9 | 172 | 19.8 | 3,684 | 19.8 |

| 50–74 | 507 | 59.5 | 581 | 66.9 | 11,359 | 61.2 |

| ≥75 | 86 | 10.1 | 71 | 8.2 | 2,404 | 12.9 |

| Histology | ||||||

| Ductal | 690 | 81.0 | 674 | 77.6 | 14,875 | 80.1 |

| Lobular | 93 | 10.9 | 97 | 11.2 | 2,025 | 10.9 |

| Other | 69 | 8.1 | 97 | 11.2 | 1,668 | 9.0 |

| Tumor size, cm | ||||||

| ≤2 | 501 | 58.8 | 602 | 69.4 | 11,249 | 60.6 |

| >2–5 | 321 | 37.7 | 238 | 27.4 | 6,650 | 35.8 |

| >5 | 18 | 2.1 | 21 | 2.4 | 517 | 2.8 |

| Unknown | 12 | 1.4 | 7 | 0.8 | 152 | 0.8 |

| Lymph node status | ||||||

| Negative | 543 | 63.7 | 640 | 73.7 | 11,333 | 61.0 |

| 1–3 positive | 229 | 26.9 | 150 | 17.3 | 4,985 | 26.8 |

| >3 positive | 63 | 7.4 | 64 | 7.4 | 1,988 | 10.7 |

| Unknown | 17 | 2.0 | 14 | 1.6 | 262 | 1.4 |

| Tumor grade | ||||||

| I | 138 | 16.2 | 234 | 27.0 | 3,854 | 20.8 |

| II | 344 | 40.4 | 374 | 43.1 | 7,667 | 41.3 |

| III | 298 | 35.0 | 198 | 22.8 | 5,719 | 30.8 |

| Unknown | 72 | 8.5 | 62 | 7.1 | 1,328 | 7.2 |

| Hormone status | ||||||

| ER&PR− | 196 | 23.0 | 127 | 14.6 | 3,091 | 16.6 |

| ER/PR+ | 632 | 74.2 | 709 | 81.7 | 14,894 | 80.2 |

| Unknown | 24 | 2.8 | 32 | 3.7 | 583 | 3.1 |

| HER2neu status | ||||||

| Negative | 381 | 44.7 | 376 | 43.3 | 8,108 | 43.7 |

| Positive | 95 | 11.2 | 59 | 6.8 | 1,720 | 9.3 |

| Unknown | 376 | 44.1 | 433 | 49.9 | 8,740 | 47.1 |

| Multifocality | ||||||

| No | 694 | 81.5 | 715 | 82.4 | 15,294 | 82.4 |

| Yes | 118 | 13.8 | 119 | 13.7 | 2,323 | 12.5 |

| Unknown | 40 | 4.7 | 34 | 3.9 | 951 | 5.1 |

| Type of surgery | ||||||

| Lumpectomy | 459 | 53.9 | 516 | 59.4 | 10,444 | 56.2 |

| Mastectomy | 393 | 46.1 | 352 | 40.6 | 8,124 | 43.8 |

| Axillary lymph node dissection | ||||||

| No | 447 | 52.5 | 526 | 60.6 | 9,140 | 49.2 |

| Yes | 405 | 47.5 | 342 | 39.4 | 9,428 | 50.8 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| No | 603 | 70.8 | 643 | 74.1 | 12,021 | 64.7 |

| Yes | 249 | 29.2 | 225 | 25.9 | 6,547 | 35.3 |

| Radiotherapy | ||||||

| No | 359 | 42.1 | 279 | 32.1 | 6,357 | 34.2 |

| Yes | 493 | 57.9 | 589 | 67.9 | 12,211 | 65.8 |

| Endocrine therapy | ||||||

| No | 593 | 69.6 | 643 | 74.1 | 10,601 | 57.1 |

| Yes | 259 | 30.4 | 225 | 25.9 | 7,967 | 42.9 |

Abbreviations: ER, estrogen receptor; HER2neu, human epidermal growth receptor 2; LRR, locoregional recurrence; PR, progesterone receptor; SP, second primary tumor.

Risk of Current Age Groups and Comparison with Screening Population

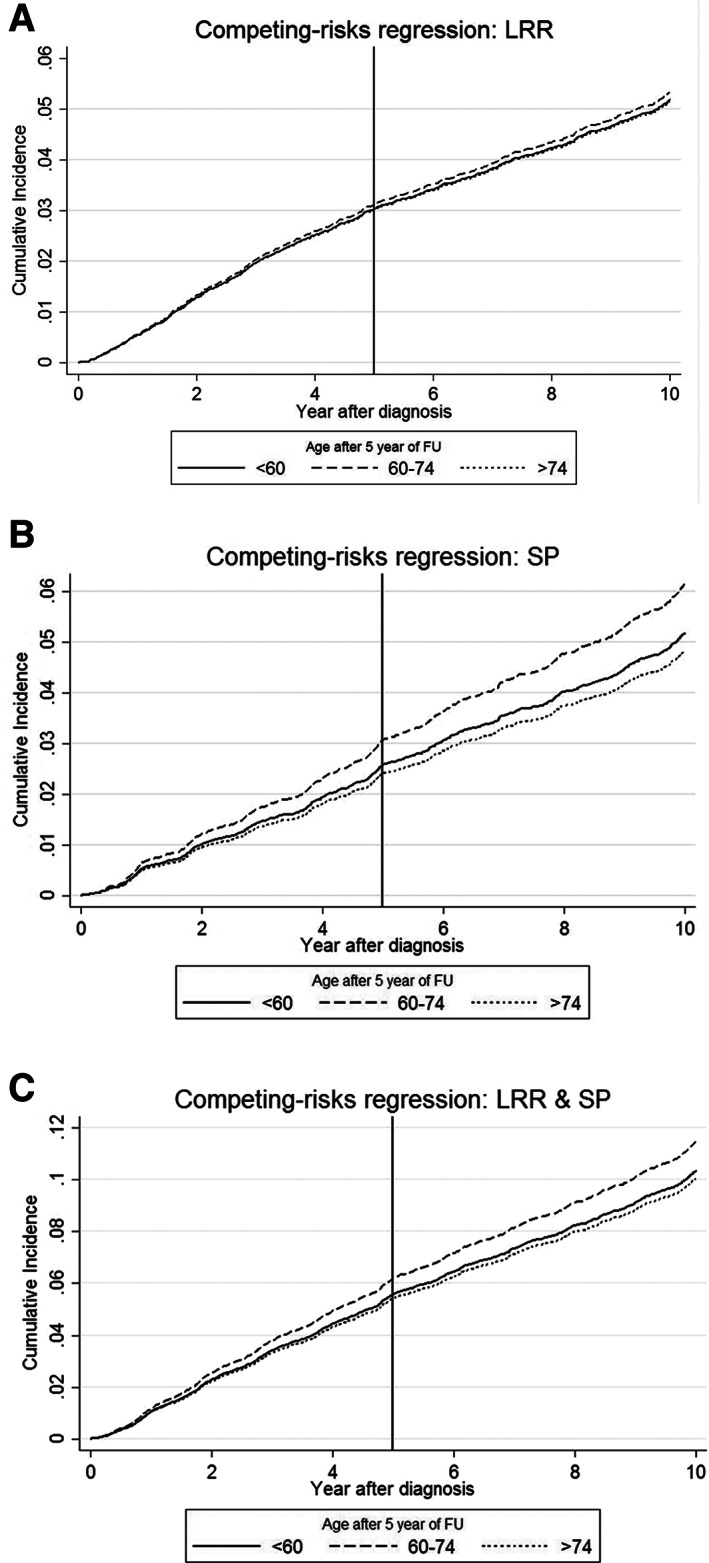

The cumulative incidence of LRR and SP combined in the first 5 years of follow‐up of the complete population was 5.7%. In this period, the cumulative LRR risk, corrected for competing risks, was overlapping for women aged <60 and >74 and slightly higher for women aged 60–74 (Fig. 1A). The differences were not significant, as 95% CIs were overlapping (data not shown). After 5 years of follow‐up, this pattern of the cumulative risk of LRR for the age groups remained the same, unlike the recommendations for follow‐up.

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence functions during 10 years of follow‐up stratified by age. (A): LRR. (B): SP. (C): LRR and SP combined.

Abbreviations: FU, follow‐up; LRR, locoregional recurrence; SP, secondary primary tumor.

The cumulative incidence of SP (Fig. 1B) was significantly higher for women aged 60–74 during the 10 years of follow‐up than women aged <60 or >74. Subsequently, the cumulative incidence for LRR and SP together followed the same pattern and was higher as well for women aged 60–74 than the risk of women aged <60 and >74 years (Fig. 1C). This effect could also be seen in the sHR values from the multivariable analysis (<60 vs. 60–74: sHR 1.07, p = .423; <60 vs. >74: sHR 0.74, p = .010). Other factors from the multivariable analysis (Table 2) with both a greater and significant effect on the risk of recurrence than age were receiving endocrine treatment (sHR 0.52, p < .001, vs. no endocrine treatment), chemotherapy (sHR 0.58, p < .001, vs. no chemotherapy), and grade of differentiation (grade II: sHR 1.25, p = .021, vs. grade I; grade III: sHR 1.34, p = .015, vs. grade I).

Table 2.

Multivariable competing risk regression

| Characteristics | sHR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||

| <60 | Ref. | ||

| 60–74 | 1.07 | 0.91–1.25 | .426 |

| ≥75 | 0.74 | 0.59–0.93 | .010 |

| Histology | |||

| Ductal | Ref. | ||

| Lobular | 1.00 | 0.78–1.27 | 1.000* |

| Mixed | 1.08 | 0.77–1.52 | .656 |

| Other | 1.10 | 0.80–1.51 | .550 |

| Tumor size, cm | |||

| ≤2 | Ref. | ||

| >2–5 | 1.23 | 1.05–1.45 | .012 |

| >5 | 1.32 | 0.83–2.09 | .242 |

| Lymph node status | |||

| Negative | Ref. | ||

| 1–3 positive | 1.04 | 0.81–1.34 | .762 |

| >3 positive | 1.05 | 0.71–1.56 | .812 |

| Tumor grade | |||

| I | Ref. | ||

| II | 1.25 | 1.03–1.51 | .023 |

| III | 1.34 | 1.06–1.70 | .014 |

| Hormone status | |||

| ER&PR− | Ref. | ||

| ER/PR+ | 1.11 | 0.87–1.40 | .404 |

| HER2neu status | |||

| Negative | Ref. | ||

| Positive | 0.96 | 0.79–1.17 | .688 |

| Multifocality | |||

| Yes | Ref. | ||

| No | 1.24 | 1.01–1.52 | .041 |

| Type of surgery | |||

| Lumpectomy | Ref. | ||

| Mastectomy | 1.02 | 0.74–1.41 | .891 |

| Axillary lymph node dissection | |||

| Yes | Ref. | ||

| No | 1.09 | 0.88–1.36 | .427 |

| Chemotherapy | |||

| No | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 0.63 | 0.51–0.78 | <.001 |

| Radiation therapy | |||

| No | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 0.80 | 0.57–1.11 | .176 |

| Endocrine therapy | |||

| No | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 0.51 | 0.41–0.62 | <.001 |

Rounded value.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ER, estrogen receptor; HER2neu, human epidermal growth receptor 2; PR, progesterone receptor; sHR, subhazard ratio.

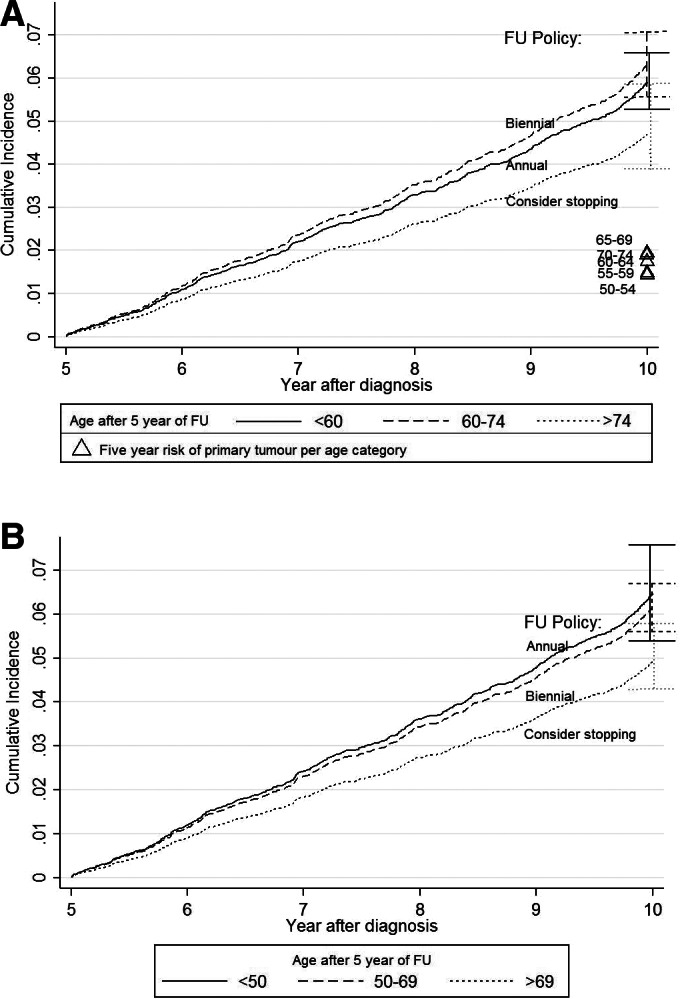

The cumulative incidence of LRR during the years 5–10 of follow‐up for women with a history of breast cancer was 2.7% (95% CI 2.3–3.2), 2.6% (95% CI 2.2–3.1), and 2.1% (95% CI 1.6–2.9) for women aged <60, 60–74, and >74, respectively, all slightly higher than the 5‐year risk of a primary tumor in the healthy screening population (ranging from 1.4% to 1.9%). Also, the cumulative incidence of SP was higher, with risks of 3.1% (95% CI 2.7–3.6), 3.7% (95% CI 3.2–4.3), and 2.6% (95% CI 1.9–3.4) for women aged <60, 60–74, and >74, respectively. LRR and SP combined resulted in at least twice the risk of recurrence in women with a history of breast cancer (<60: 5.9%, 95% CI 5.3–6.6; 60–74: 6.3%, 95% CI 5.6–7.1; >74: 4.7%, 95% CI 3.9–5.9), compared with the risk of a primary tumor in the healthy screening population (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence functions with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for (A) the current age categories during years 5–10 of follow‐up for locoregional recurrence (LRR) and secondary primary tumor (SP) combined, compared with the risk of a primary tumor in the healthy screening population (Δ) having biennial screening, divided in 5‐year age categories, and (B) LRR and SP combined after 5 years of follow‐up using the proposed age cutoffs. Note how the first two risk groups switch: with the proposed cutoffs, the highest risk group (<50) receives annual follow‐up after 5 years and the lower risk group (50–69) biennial follow‐up.

Abbreviation: FU, follow‐up.

Alternative Age Cutoffs

As the age‐based follow‐up recommendations after 5 years of follow‐up did not match with the actual risk (as after 5 years of follow‐up, the risks of LRR or SP was highest for the age group 60–74 with biennial follow‐up, whereas the age group <60 has lower risk and is recommended annual follow‐up), alternative age cutoffs were assessed. The cumulative incidence functions for the current age cutoffs during 10 years of follow‐up are depicted in Figure 1C. After testing between 5‐yearly cutoffs, significant differences in events were found between the age groups <50, 50–69, and >69 years after 5 years of follow‐up. The corresponding cumulative incidences in the years 5–10 of follow‐up were 6.5% (95% CI 5.4–7.6) for the group aged <50, 6.2% (95% CI 5.6–6.7) for ages 50–69, and 4.9% (95% CI 4.3–5.8) for women >69 years. As the risk is especially high in relatively young women, the new age cutoffs enable that the first risk group (<50 after 5 years) has both the highest risk and the most intensive follow‐up recommendation (Fig. 2B). So if follow‐up recommendations were to be based on age only, the new cutoffs are more in accordance with the risk of LRR and SP. This could also be seen from the multivariable analysis (<50 vs. 50–69: sHR 0.82, p = .050; <50 vs. >69: sHR 0.63, p < .001; Table 2).

Discussion

Using competing risk regression, we found that the current age‐based recommendations for patients with breast cancer after 5 years of follow‐up do not match with the actual risk of LRR and SP: the risk was lower for women aged <60 years after 5 years of follow‐up who received annual follow‐up, compared with women aged 60–74 receiving less intensive biennial follow‐up. This contradiction was caused by the relatively low risk of the 50‐ to 60‐year‐old group, which lowered the risk of the complete group, including the age group of younger women (<50 after 5 years of follow‐up, <45 at diagnosis) with higher risks. With alternative cutoffs for the age groups (<50, 50–69, >69), this higher‐risk group was separated from the women with lower risk (aged 50–60) and more differentiation was achieved, resulting in recommendations that better match the actual risk. When comparing with the 5‐year risk of primary breast cancer in different age groups of women without a history of breast cancer that are invited to the biennial national screening program, the risk of LRR and SP after 5 years of clinical follow‐up was at least twice as high. Still, other factors than age were of greater influence on recurrence risk and should also be taken into account.

The large size of this study cohort from the population‐based NCR strengthens the reliability and generalizability of the results. Because of the required long follow‐up for our study, the data from 2003 and 2005 might not be generalizable to the current situation, as treatments have improved over time, resulting in lower recurrence risk. For example, the addition of trastuzumab to chemotherapy for HER2‐positive tumors was not yet advised in the guideline in the year 2003, which means that patients in this cohort did not receive this treatment [3]. Still, the benefit of this treatment in the following years can be supposed by the nonsignificant sHR of 0.96 for HER2‐positive tumors. A positive hormonal receptor status, on the other hand, suggested a nonsignificant negative effect (sHR 1.11 for ER/PR+ compared with ER&PR−). However, when the endpoints were assessed separately, we see other (nonsignificant) outcomes: sHR of 0.94 (95% CI 0.71–1.24) for LRR and 1.29 (95% CI 0.99–1.67) for SP.

The probability of recurrence was compared with the risk of a primary tumor in the healthy population and not the hazard rate, as with competing risks the one‐to‐one relationship between rate and risk is lost (i.e., the hazard of recurrence will not be equal to the risk of recurrence) [33]. Consequently, the way in which covariates (like age) are associated with the outcome may not coincide. The comparison with the healthy screening population was made with different incidence years (2005–2009) than women at risk for recurrence (2008–2013 for 2003 and 2010–2015 for 2005). This could have led to slight changes in risk, but it is unlikely that this has led to different results. With the alternative age cutoff, the recommendations for women aged 50–69 after 5 years of follow‐up would be the same in both the follow‐up and the screening setting (biennial). The risk of both LRR and SP combined resulted in at least twice the risk of recurrence in women with a history of breast cancer, compared with the risk of a primary tumor in the healthy screening population. This means that patients in the follow‐up aged 60–74 undergo the same frequency of visits as patients in the screening setting, who have half the risk. This does not necessarily mean that follow‐up should be intensified or that screening should be less intensive; rather, it points out that there is a lot to be gained from personalization. Personalizing screening is of increasing interest and is currently being studied [34, 35]. Furthermore, there are some differences between screening and follow‐up, as for example women with a history of breast cancer undergo both mammography and a physical examination. Also, primary tumors are thought to grow slower than LRR [36], which leads to a larger sojourn time.

Although many patients with breast cancer report reassurance from frequent follow‐up, clinic visits and possible false‐positive tests also cause unwarranted effects such as anxiety [7]. A reduction of unnecessary follow‐up visits can reduce this discomfort, especially in light of the limited evidence on a possible survival benefit. A personalized follow‐up could also reduce unnecessary use of valuable capacity, shorten the waiting lists for diagnostics tests and other services required for follow‐up. The impact of less resource‐intensive follow‐up has already been assessed and found to be cost‐effective, but the differences in the risk of recurrent disease were not considered [37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42]. In this study, we only considered the follow‐up visits aimed at detection of recurrent disease in an early stage. No conclusions can be made based on this study for the visits that offer psychosocial care. When a detected tumor would not have become symptomatic during a woman's lifetime, this is considered overdiagnosis [43]. Overdiagnosis increases in the highest age group, as the risk of death due to other causes also rises. Because mammography is less sensitive and specific in women <50 years, the net benefit of follow‐up is this age group is probably also lower. However, the longer life expectancy of this group compared with the elderly increases the benefit. Moreover, more sensitive diagnostic tools such as magnetic resonance imaging are progressively more used in patients at higher risk for LRR or SP.

Using the alternative cutoffs for age would lead to more risk‐based recommendations, as especially young women (<50 after 5‐year follow‐up) bear higher risks. These young women tend to have higher‐grade primary ductal tumors with positive lymph nodes and to receive endocrine and chemotherapy more often than the older age groups (data not shown). Although the new cutoffs lead to a more risk‐based follow‐up, there was still overlap in the confidence intervals. As only data on diagnosis and no data on timing and results from previous follow‐up testing were available from the NCR, the effect of this more risk‐based strategy (e.g., which recurrences would be detected “late”) could not be assessed. With stratification only based on age, it is not possible to accurately discriminate low‐ from high‐risk patients. In previous studies, we developed a prediction model for the first 5 years of risk of recurrence that revealed other factors such as receptor status, stage, and treatment that all influence recurrence risks. To achieve a more detailed personalized risk estimate after 5 years of follow‐up, multiple risk factors should be taken into account. The INFLUENCE nomogram is a prediction model and web‐based nomogram (www.utwente.nl/influence) for individual time‐dependent LRR risk for 5 years [8]. It was developed based on 37,278 patients diagnosed with early breast cancer between 2003 and 2006. The model was also externally validated and provides valid and reliable estimates for patients with a follow‐up of 5 years [44]. However, it does not include the risk on SP. When this model is combined with SP risk and accurate thresholds, personalized follow‐up schedules based on estimated individual risks can be offered. Ideally, comorbidity should be taken into account as well. However, evidence for this is limited and practice guidelines are missing [2].

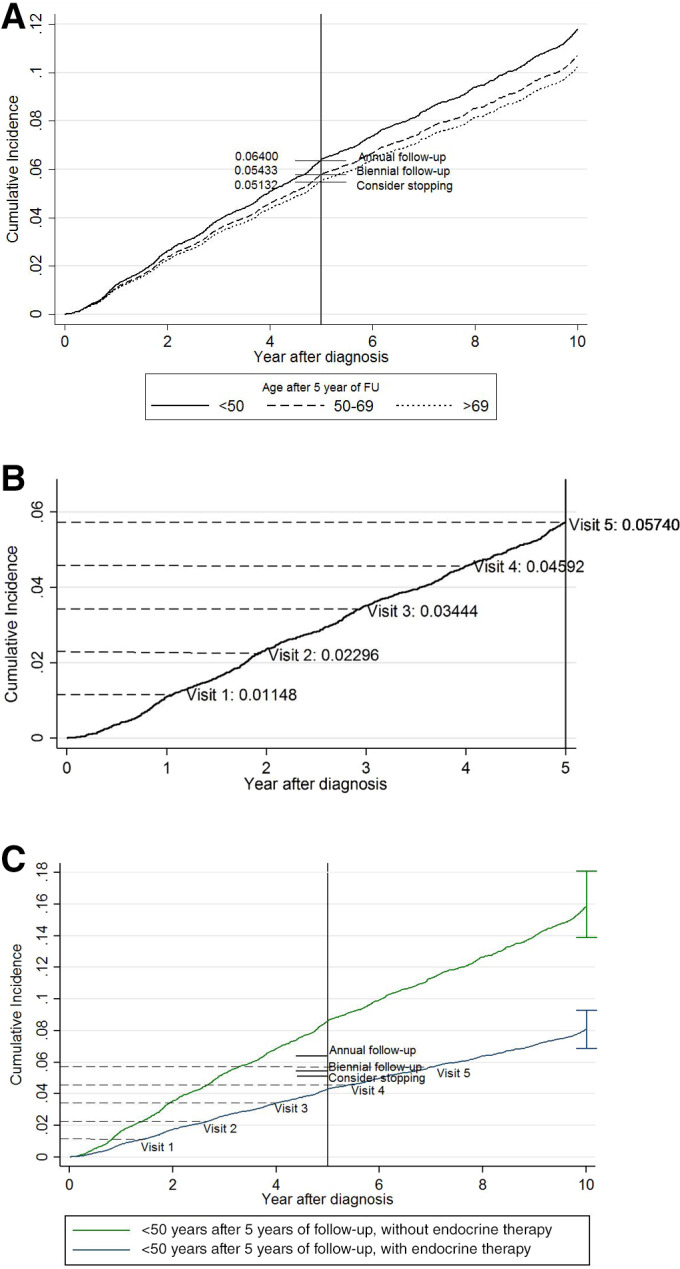

A simple example of thresholds would be to use the cumulative incidence levels after 5 years of follow‐up of the newly defined groups based on the alternative age cutoffs (Fig. 3A) as risk thresholds for the follow‐up frequency (annual, biennial, or consider stopping hospital follow‐up). Subsequently, cumulative incidence level of the complete population during the first 5 years (5.74%) could be divided in five equal intervals (1.15% per annual visit) and used to determine when a follow‐up visit should take place: instead of set yearly intervals, only when the risk level is reached (Fig. 3B). When projecting these thresholds on two patient profiles based on age (<50) and endocrine treatment (yes, no), it can be seen that although the two groups receive the same annual follow‐up in practice, the risk of women with endocrine therapy is half that of women without and below the risk level of women aged >69 (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Examples of risk groups to illustrate the imbalance between the risk and recommendations based on age‐related thresholds. (A): Cumulative incidence of locoregional recurrence (LRR) and secondary primary tumor (SP) combined over 10 years of follow‐up using the proposed age cutoffs after 5 years and the corresponding recommendations. (B): Cumulative incidence of combined LRR and SP of the entire population to determine equally spaced risk intervals per visit, to propose a follow‐up visit only when the risk level is reached (not at set time periods). (C): Cumulative incidence of LRR and SP combined with 95% confidence intervals for two example risk groups based on age (<50) and endocrine therapy (yes/no), showing significant differences in risk within one age group. On the cumulative incidence functions, the risk intervals for the first five visits (as depicted in B) are projected. Based on these simple thresholds, the high risk group might benefit from more frequent visits, as it reaches the risk level of the entire population (visit 5) already after 3 years, whereas it takes around 7 years for the lower risk group. However, these thresholds only take into account the risk and current recommendations, not the benefits and harms.

Abbreviation: FU, follow‐up.

Although there is a difference in risk using other age cutoffs, the differences are not large. This raises the question whether there should be a difference in recommendation at all and exemplifies that age, or any single risk factor for that matter, is not able to capture the risk differences in women at risk for recurrence and is not sufficient for determining follow‐up. The above thresholds are based on age and the current recommendations. Better would be to take into account the clinical relevance of the risk, as well as the growth rate of tumors and the metastatic potential (e.g., it is better to detect a triple‐negative tumor as early as possible, and for a luminal A tumor, detection is less urgent). However, this was meant to give insight into the room for improvement of follow‐up. In a more comprehensive model for follow‐up, besides taking into account the individual risk of recurrent disease, there should be a weighted balance between the possible benefits (earlier detection and corresponding survival) and harms of follow‐up (testing itself, false positives, overdiagnosis, and financial toxicity) that should be addressed to get toward personalized risk‐based follow‐up combined with informed clinical decision making. Moreover, part of the follow‐up consists of the identification of need of psychosocial support, which could be tailored based on outcomes of quality of life surveys and patient preferences.

Conclusion

The current consensus‐based follow‐up recommendations after 5 years (annual for <60 years after 5 years of follow‐up, biennial for 60–74, consider stopping >74) use suboptimal age cutoffs leading to an imbalance between risk of LRR and SP and intensity of the follow‐up following the 5 years of clinical follow‐up. Patients aged 50–60 years have a lower risk for recurrence compared with patients <50 and could have a less intensive schedule. The proposed alternative cutoffs (<50, 50–69, >69) will lead to a more balanced risk‐based follow‐up frequency taking into account the risk of both LRR and SP and will be a start toward more efficient allocation of resources. However, to get truly personalized follow‐up, more risk factors as well as the benefits and harms of follow‐up should be taken into account to provide accurate individualized risk estimates and follow‐up schedules.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Annemieke Witteveen, Sabine Siesling

Provision of study material or patients: Annemieke Witteveen, Linda de Munck, Sabine Siesling

Collection and/or assembly of data: Annemieke Witteveen, Linda de Munck, Sabine Siesling

Data analysis and interpretation: Annemieke Witteveen, Linda de Munck, Catharina G.M. Groothuis‐Oudshoorn, Gabe S. Sonke, Philip M. Poortmans, Liesbeth J. Boersma, Marjolein L. Smidt, Sabine Siesling

Manuscript writing: Annemieke Witteveen, Linda de Munck, Catharina G.M. Groothuis‐Oudshoorn, Gabe S. Sonke, Philip M. Poortmans, Liesbeth J. Boersma, Marjolein L. Smidt, Ingrid M.H. Vliegen, Maarten J. IJzerman, Sabine Siesling

Final approval of manuscript: Annemieke Witteveen, Linda de Munck, Catharina G.M. Groothuis‐Oudshoorn, Gabe S. Sonke, Philip M. Poortmans, Liesbeth J. Boersma, Marjolein L. Smidt, Ingrid M.H. Vliegen, Maarten J. IJzerman, Sabine Siesling

Disclosures

Gabe S. Sonke: AstraZeneca, Merck, Novartis, Roche (RF [to institution]); Marjolein L. Smidt: Servier Pharma (RF). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

Acknowledgments

We thank the registrars of the Netherlands Cancer Registry for their effort in gathering the data essential to this study. The authors had consent from the Advisory Committee of the Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organisation (IKNL). The study did not need approval of the Medical Ethical Committee (METc) because there was no direct patient contact, and according to local regulations in The Netherlands (WMO), only studies with high burden for patients have to be reviewed.

Disclosures of potential conflicts of interest may be found at the end of this article.

No part of this article may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form or for any means without the prior permission in writing from the copyright holder. For information on purchasing reprints contact Commercialreprints@wiley.com. For permission information contact permissions@wiley.com.

References

- 1. Grandjean I, Kwast ABG, de Vries H et al. Evaluation of the adherence to follow‐up care guidelines for women with breast cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2012;16:281–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Runowicz CD, Leach CR, Henry NL et al. American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline. CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66:43–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organisation (IKNL) (2012) Dutch breast cancer guideline. Available at http://www.oncoline.nl/breastcancer. Accessed March 2, 2019.

- 4. Rosselli MDT, Cariddi A. Intensive diagnostic follow‐up after treatment of primary breast cancer. A randomized trial. J Am Med Assoc 1994;271:1593–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Geurts SME, De Vegt F, Siesling S et al. Pattern of follow‐up care and early relapse detection in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012;136:859–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pennery E, Mallet J. A preliminary study of patients' perceptions of routine follow‐up after treatment for breast cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2000;4:138–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Allen A. The meaning of the breast cancer follow‐up experience for the women who attend. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2002;6:155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Witteveen A, Vliegen IMH, Sonke GS et al. Personalisation of breast cancer follow‐up: A time‐dependent prognostic nomogram for the estimation of annual risk of locoregional recurrence in early breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2015;152:627–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van Laar C, van der Sangen MJC, Poortmans PMP et al. Local recurrence following breast‐conserving treatment in women aged 40 years or younger: Trends in risk and the impact on prognosis in a population‐based cohort of 1143 patients. Eur J Cancer 2013;49:3093–3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim SH, Simkovich‐Heerdt A, Tran KN et al. Women 35 years of age or younger have higher locoregional relapse rates after undergoing breast conservation therapy. J Am Coll Surg 1998;187:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE ). Early and locally advanced breast cancer: Diagnosis and treatment (CG80). Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg80/chapter/guidance#follow‐up. Accessed July 1, 2018. [PubMed]

- 12. Australia Cancer (2011). Recommendations for follow‐up of women with early breast cancer. Available at http://guidelines.canceraustralia.gov.au/guidelines/early_breast_cancer/ch01s03.php. .

- 13. Runowicz CD, Leach CR, Henry NL et al. American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1078–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Van Buuren S, Groothuis‐Oudshoorn K. mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J Stat Softw 2011;45:631–645. [Google Scholar]

- 15. White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med 2011;30:377–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marshall A, Altman DG, Holder RL et al. Combining estimates of interest in prognostic modelling studies after multiple imputation: Current practice and guidelines. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009;9:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moossdorff M, van Roozendaal LM, Strobbe LJA et al. Maastricht Delphi Consensus on Event Definitions for Classification of Recurrence in Breast Cancer Research. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 19. van Maaren MC, de Munck L, Jobsen JJ et al. Breast‐conserving therapy versus mastectomy in T1‐2N2 stage breast cancer: A population‐based study on 10‐year overall, relative, and distant metastasis‐free survival in 3071 patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2016;160:511–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) . Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15‐year survival: An overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 2005;365:1687–1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Begg CB, Haile RW, Borg A et al. Variation of breast cancer risk among BRCA1/2 carriers. JAMA 2008;299:194–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dieci MV, Arnedos M, Delaloge S et al. Quantification of residual risk of relapse in breast cancer patients optimally treated. Breast 2013;22(suppl 2):S92–S95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Davies C, Godwin J, Gray R et al. Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: Patient‐level meta‐analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 2011;378:771–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gamucci T, Vaccaro A, Ciancola F et al. Recurrence risk in small, node‐negative, early breast cancer: A multicenter retrospective analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2013;139:853–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lin PH, Yeh MH, Liu LC et al. Clinical and pathologic risk factors of tumor recurrence in patients with node‐negative early breast cancer after mastectomy. J Surg Oncol 2013;108:352–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Komoike Y, Akiyama F, Iino Y et al. Ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence (IBTR) after breast‐conserving treatment for early breast cancer: Risk factors and impact on distant metastases. Cancer 2006;106:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cortesi L, Marcheselli L, Guarneri V et al. Tumor size, node status, grading, HER2 and estrogen receptor status still retain a strong value in patients with operable breast cancer diagnosed in recent years. Int J Cancer 2013;132:E58–E65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Clarke M, Collins R, Darby S et al. Effects of radiotherapy and of differences in the extent of surgery for early breast cancer on local recurrence and 15‐year survival: An overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 2005;366:2087–2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Benson JR, Wishart GC. Predictors of recurrence for ductal carcinoma in situ after breast‐conserving surgery. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:e348–e357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nagao T, Kinoshita T, Tamura N et al. Locoregional recurrence risk factors in breast cancer patients with positive axillary lymph nodes and the impact of postmastectomy radiotherapy. Int J Clin Oncol 2013;18:54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Campbell EJ, Tesson M, Doogan F et al. The combined endocrine receptor in breast cancer, a novel approach to traditional hormone receptor interpretation and a better discriminator of outcome than ER and PR alone. Br J Cancer 2016;115:967–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organisation (IKNL) (2019). Dutch Cancer Figures. Available at https://www.cijfersoverkanker.nl/?language=en. Accessed December 1, 2019.

- 33. Andersen PK, Geskus RB, de Witte T et al. Competing risks in epidemiology: Possibilities and pitfalls. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41:861–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ripping TM, Hubbard RA, Otten JDM et al. Towards personalized screening: Cumulative risk of breast cancer screening outcomes in women with and without a first‐degree relative with a history of breast cancer. Int J Cancer 2016;138:1619–1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shieh Y, Eklund M, Madlensky L et al. Breast cancer screening in the precision medicine era: Risk‐based screening in a population‐based trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2017;109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hölzel D, Emeny RT, Engel J. True local recurrences do not metastasize. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2011;30:161–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Robertson C, Ragupathy SKA, Boachie C et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost‐ effectiveness of different surveillance mammography regimens after the treatment for primary breast cancer: Systematic reviews, registry database analyses and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2011;15:v–vi, 1–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rojas MP, Telaro E, Russo A et al. Follow‐up strategies for women treated for early breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005:CD001768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kirshbaum MN, Dent J, Stephenson J et al. Open access follow‐up care for early breast cancer: A randomised controlled quality of life analysis. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2017;26:e12577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Koinberg I, Engholm GB, Genell A. A health economic evaluation of follow‐up after breast cancer surgery: Results of an RCT study. Acta Oncol 2009;48:99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Benning TM, Kimman ML, Dirksen CD et al. Combining individual‐level discrete choice experiment estimates and costs to inform health care management decisions about customized care: The case of follow‐up strategies after breast cancer treatment. Value Health 2012;15:680–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kimman ML, Dirksen CD, Voogd AC et al. Economic evaluation of four follow‐up strategies after curative treatment for breast cancer: Results of an RCT. Eur J Cancer 2011;47:1175–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gunsoy NB, Garcia‐Closas M, Moss SM. Modelling the overdiagnosis of breast cancer due to mammography screening in women aged 40 to 49 in the United Kingdom. Breast Cancer Res 2012;14:R152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Voelkel V, Draeger T, Groothuis‐Oudshoorn CGM et al. Predicting the risk of locoregional recurrence after early breast cancer: An external validation of the Dutch INFLUENCE‐nomogram with clinical cancer registry data from Germany. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2019;145:1823–1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]