Abstract

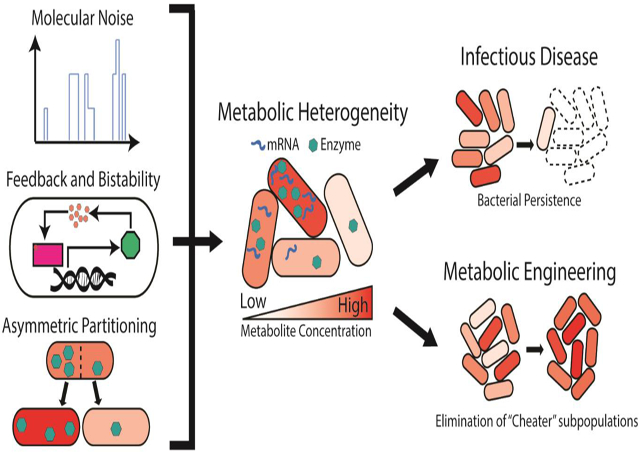

Bacteria within an isoclonal population display significant heterogeneity in metabolism, even under tightly controlled environmental conditions. Metabolic heterogeneity enables influential functions not possible or measurable at the ensemble scale. Several molecular and cellular mechanisms are likely to give rise to metabolic heterogeneity including molecular noise in metabolic enzyme expression, positive feedback loops, and asymmetric partitioning of cellular components during cell division. Dissection of the mechanistic origins of metabolic heterogeneity has been enabled by recent developments in single-cell analytical tools. Finally, we provide a discussion of recent studies examining the importance of metabolic heterogeneity in applied settings such as infectious disease and metabolic engineering.

Keywords: Metabolic Heterogeneity, Phenotypic Heterogeneity, Persistence, Persisters, Metabolic engineering, Stochastic, Noise, Partitioning, Division, Raman, Biosensor, NanoSIMS, PopQC, Heterogeneity, Variation, Infectious Disease

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

Introduction

Bacteria within isogenic populations consistently feature phenotypic variation, even under identical environmental conditions. Examining phenotypic heterogeneity at the single cell level often yields insights that are exceptionally relevant to the function of the overall population, yet not captured in bulk measurements[1]. For example, a given feature of a subpopulation may strongly predict which cells survive environmental changes, or bestow advantages to the population at the expense of the individual[2]. One important but largely unexplored type of phenotypic heterogeneity lies in cell-to-cell variations in metabolite levels and dynamics. Not only are these directly relevant to function, but they also strongly influence other cellular processes such as translation and growth. Thus, assessment of cellular metabolic heterogeneity and what causes it is indispensable towards fully understanding the behavior of a bacterial population. While methods to assess gene expression at the single cell level are well established, the diversity in chemical structure and rapid turnover dynamics of metabolites posits an ongoing challenge in assessing metabolic heterogeneity. Developments in single-cell instrumentation and molecular tools that allow quantitation of specific metabolites have just begun to enable investigations into both fundamental principles and several applied settings. Other focused reviews have covered related topics such as single-cell technologies for bacteria [3] and the relevance of heterogeneity in metabolic engineering [4,5]. Here, we provide an integrative overview of core concepts and recent progress across several topics in the field of bacterial metabolic heterogeneity. These include its biological origins and purposes, tools and innovative approaches to characterize it, and its applications in settings such as infectious disease and metabolic engineering. We focus mostly on findings from isoclonal populations of symmetric bacteria such as Escherichia coli, while metabolic heterogeneity caused by genetic variation or observed in asymmetric bacteria such as Caulobacter crescentus will not be discussed.

Fundamentals of bacterial metabolic heterogeneity

Variability in bacterial single cell metabolism has previously been attributed to microenvironmental differences, and these are known to have relevance in disease or bioproduction outcomes[6,7]. However, recent studies discovered significant metabolic heterogeneity even under the most idealized laboratory conditions, suggesting it is a fundamental feature of bacterial populations. Heterogeneity has been observed in many diverse nodes of bacterial metabolism to date, including central carbon metabolism[8,9], fatty acid biosynthesis [10], pyruvate-sensing networks[11], ATP[12], ribosome content[13-15], and amino acid pathways [16]. Depending on the given metabolite and system, cell metabolite distributions can range from narrow to broadly unimodal, or even multimodal [17]. Here, we discuss the basic biological relevance of metabolic heterogeneity and underlying molecular and cellular causes.

Much of the functional relevance of metabolic heterogeneity in natural settings can be conceptualized as “bet hedging”, where heterogeneity increases the likelihood that some subpopulation will survive a future stress. The phenomenon of arrested growth upon nutrient shifts serves as an excellent example. Here, homogenous responsive switching was once thought to explain resumed growth after a lag[8]. However, it is now known that many cells remain quiescent and are outperformed by expanding subpopulations better adapted to the new environment [8,9,18]. Klebsiella oxytoca, for example, exhibited a remarkable heterogeneity in nitrogen fixation when exogenous nitrogen (ammonia, NH4+) is slightly limited. Under this condition, cells with high nitrogen fixation capability had a significant growth advantage during subsequent NH4+ removal [19]. In contrast, cells equilibrated in either starved or high exogenous nitrogen conditions show expected high or low nitrogen fixation with minimal heterogeneity and are less adaptive to condition changes. Overall, these examples illustrate how metabolic heterogeneity ensures survival in changing environments.

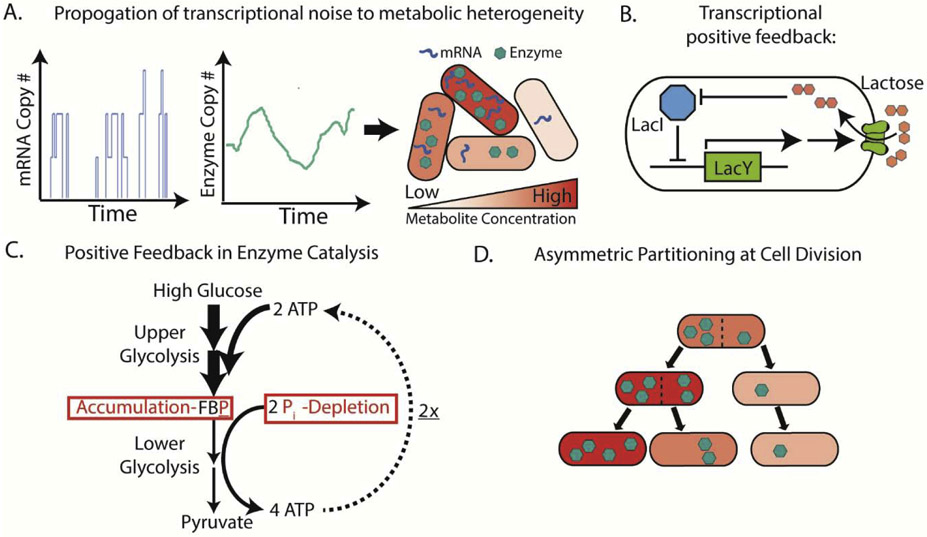

What are the primary molecular mechanisms driving metabolic heterogeneity? First of all, basic principles governing noise in transcription and translation lead to variations in the abundance of metabolic enzymes, and in turn, affect levels of the metabolites they produce [20] (Figure 1A). Transcription is especially stochastic, occurs in bursting patterns, and leads to high variabilities in mRNA between single cells. This makes low-abundant proteins have particularly high variabilities when propagated to translation[21]. Even for high-abundant proteins, cell-to-cell variations in gene-extrinsic factors, such as ribosomes or RNA polymerases, contribute to heterogeneity in protein expression [21,22]. Interestingly, metabolic genes tend to be controlled by noisier promoters, while essential genes are often controlled by the least noisy promoters [23]. Such observations suggest that cells may explore a greater variation in enzyme expression to obtain large metabolic heterogeneity. Indeed, stochastic modeling using measured enzyme variability shows this alone can generate large metabolic heterogeneity within an isogenic population [20]. At the extreme end of possibility, stochastic expression can even lead to bimodal expression without bistability [24]. This is particularly consequential for transcription factors that regulate metabolic genes as variability can be readily transmitted to metabolic heterogeneity. In Pseudomonas Putida, expression of the transcription factor XylR follows this bimodal pattern and generate bimodal variability in xylene metabolism[25].

Figure 1: Sources of Metabolic Heterogeneity in Isogenic Bacterial Populations.

A. Transcription often occurs in stochastic bursts, leading to high variability between cells. Variability is transmitted to enzyme copy number and could lead to heterogeneity in metabolite concentration. B. Transcriptional positive feedback loop generates metabolic bistability. An example is shown where the lactose permease LacY facilitates lactose uptake. Lactose destabilizes the repressor LacI and prevents it from binding DNA. This allows further active transcription and translation of the lac operon including LacY, which then further accelerates lactose transport into the cell. Some aspects of the lac operon and regulation are omitted for simplicity. C. Positive feedback in enzymatic catalysis generates metabolic bistability. An example is shown where cells are trapped in a high-glucose-induced, growth-arrested state stabilized by an imbalance in glycolytic flux. High flux through upper glycolysis rapidly consumes ATP and assimilates generated phosphate (Pi) as fructose bisphosphate (FBP). Any Pi from other sources entering lower glycolysis is unable to rescue imbalance because generated ATP is strongly favored towards two further rounds of upper glycolysis, only further stabilizing this state. In other subpopulations and physiological conditions, regulatory mechanisms prevent this feedback from reaching stability. D. Asymmetric partitioning of cellular components upon cell division can generate heterogeneity in metabolic activity between daughter cells.

More commonly, multimodality is observed in multi-stable systems, where positive feedback regulatory architectures under molecular noise push cells to multiple stable states with distinctive phenotypes. One well-studied example is the E. coli lac operon, where lactose inactivates the repressor LacI and increases transcription of the permease lacY, which further transports more lactose inside the cell, forming a positive feedback loop and leading to two stable subpopulations/states with low and high intracellular lactose levels (Figure 1B) [26]. Additionally, metabolic multimodality can form through positive feedback of enzymatic catalysis or metabolic imbalance (Figure 1C). High-glucose induced imbalance between upper and lower glycolysis is one such case (Figure 1C). Rapid flux through upper glycolysis depletes ATP and results in fructose biphosphate accumulation. Cellular phosphate is consumed in lower glycolysis to regenerate ATP, but in the depleted state ATP is immediately channeled to upper glycolysis. Further, the 1:2 stoichiometry in ATP between lower and upper glycolysis only further ensures the accumulation of fructose biphosphate despite any further input of phosphate from other cellular sources. [27]. This results in stochastic formation of subpopulations with depleted ATP/Pi pools when this imbalance reached a critical threshold, and demonstrates how even tightly regulated pathways can reach multimodality[27]. Although this metabolic imbalance was observed in yeast, similar mechanisms may exist in bacteria[8].

Another source of metabolic heterogeneity is asymmetric partitioning of cellular components during cell division [28]. For any cellular component, the chance of asymmetric partitioning is high when it has low copy number and slow diffusion kinetics [29,30]. Most small-molecule metabolites have high copy numbers (in E. coli, 103-107 copies[31]) and rapid diffusion kinetics such that their direct asymmetric distribution is unlikely. However, daughters of the same mother cell still display different metabolic activity following division[32]. Several mechanisms could lead to different metabolic heterogeneity between daughter cells. First, asymmetric partitioning of low-abundant metabolic enzymes or extremely large enzyme complexes may cause immediate metabolic differences in daughter cells upon division [29]. Second, transcription factors that regulate metabolic pathways often have relatively low copy number, and their asymmetric partitioning could lead to different expression level of pathway enzymes. For an end product of a metabolic pathway, its concentration can takes as many as seven cell cycles to reach steady state upon transcriptional activation or repression[33]. Thus, metabolic variability may not be observed right after division, but may appear over the next a few generations after asymmetric partitioning of metabolite-regulating transcriptional factors [33]. Third, asymmetric segregation of low-copy- number subcellular components, such as inclusion bodies, may cause variation in daughter cell grow rate [34], which further affect other metabolic activities. Such asymmetric partitioning often confers faster growth to daughter cells with less aggregates, and broad stress-resistance to daughter cells inheriting more aggregates[34,35]. To summarize, metabolic heterogeneity can arise from a number of molecular and cellular mechanisms and often has important implications for population-level function.

Approaches for measuring Bacterial Metabolic Heterogeneity

Recent advances in single cell instrumentation, imaging, and biochemical techniques have greatly accelerated our ability to assess metabolic heterogeneity. Two widely used class of tools for single cell assessment are chemical-based and genetically encoded metabolite biosensors, which couple concentrations of a specific metabolite to a quantitative fluorescent output [10,36]. Using such fluorescent output, metabolic heterogeneity can be measured by either flow cytometry or live cell imaging, and in certain cases fluorescence-activated cell sorting can be used to further separate cells based on their different phenotypes. Several strategies exist to construct genetically encoded metabolite biosensors. First, metabolite-responsive transcription factors can be used to turn on or off the expression of fluorescent reporters or RNA based fluorescent aptamers according to the concentration of the target metabolite [36-40]. RNA-based fluorescent aptamers carry the advantage of faster reporter kinetics versus fluorescent proteins, which require time to fold before fluorescing. Second, even faster reporting kinetics can be achieved with fluorescent resonance energy transfer (FRET) based biosensors. Here, metabolite binding induces a conformational shift that alters the proximity between a donor and acceptor fluorescent protein. Excitation of the donor fluorophore and measuring the relative emission spectra allows metabolite quantification. [36,41]. Third, metabolite-binding RNA aptamers can be used to stabilize the fluorescence of adjacent RNA-based fluorescent aptamers.This system carries similar kinetic advantages of FRET and can benefit from the large repertoire of metabolite-binding RNA aptamers or in vitro aptamer selection (also known as systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment, SELEX)[37,42]. In general, most genetically-encoded metabolite biosensors are functional in living growing cells, and thus can provide dynamic information of a metabolite at a time scale longer than the sensor’s response time. However, these sensors are limited to cells that are amenable to genetic manipulation.

Mass spectrometry is the gold standard approach for versatile and quantitative metabolite assessment. Of several mass spectrometry techniques, nanoscale secondary ion mass spectrometry (NanoSIMS) is often used for studying bacterial metabolic heterogeneity due to its exceptional subcellular resolution (~50 nm) and ability to measure several metabolic species per scan. This can be performed on non-cultivable bacteria, and as a result has found extensive applications in environmental microbiology. For example, wastewater sludge bacteria were recently found to have extensive heterogeneity in oleic acid accumulation[43], and single cell N2 and CO2 fixation were observed to correlate in Chlorobium phaeobacteroides. NanoSIMS can also be combined with prior fluorescence-based secondary analyses to further link single-cell metabolic data to many other phenotypes[44,45]. However, it is destructive and generally incapable of time-resolved measurement in single cells.

Last, Raman spectroscopy is a nondestructive technique that probes intrinsic vibrational frequencies of biomolecules, and it can be combined with microscopy for single cell evaluation. A typical output features intensity as a function of wavenumber where intensity peaks represent specific chemical bonds encompassing virtually all major classes of biomolecules. Further, combining it with stable isotope probing produces predictable peak shifts and has allowed assessment of metabolic heterogeneity in pathways of interest including carboxymethylcellulose degradation[46] and carbon catabolite repression in naphthalene-degrading bacteria[47] . Though a fairly global assessment of metabolism is useful, establishing a robust connection between specific metabolites of interest and spectra can be difficult. High-dimensional analyses correlating features of Raman spectra with specific metabolites [48] or the transcriptome[49] may improve the insights gained. In conclusion, these technologies have served as the basis for uncovering metabolic heterogeneity, and further innovation will continue to expand the scope and breadth of what can be assessed.

Applications of Metabolic Heterogeneity in Infectious Disease and Metabolic Engineering

With a basic knowledge of the underlying principles and increasingly powerful tools to measure metabolic heterogeneity, there has never been a better time to study its relevance and uses in applied settings. Two particularly promising areas for application are infectious disease and metabolic engineering.

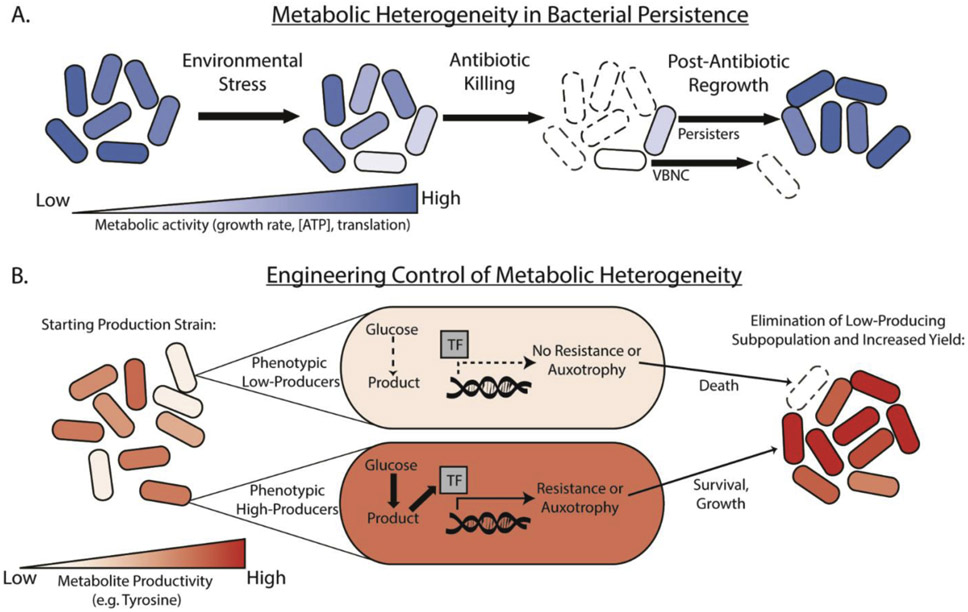

In infectious disease settings, heterogeneity in metabolism can be profoundly influential to bacterial survival, population adaptation, and infection outcomes. One example is bacterial persistence, a phenomena where small subsets of bacteria display increased phenotypic antibiotic tolerance compared to the rest of a population[50]. Post-antibiotic regrowth of persistent bacteria threatens patients and perhaps worse, is mechanistically linked to development of antibiotic resistance[51]. Metabolic heterogeneity seems to be a fundamental principle underlying persister formation, phenotypes, and regrowth (Figure 2A). First, in a manner analogous to bet-hedging, prior stress factors such as starvation [52] or nutrient shifts[8,53-55] induce metabolic heterogeneity in populations to increase persister formation. Though few specific aspects of persister metabolism are universal, they are often characterized by extremely slow growth[56], reduced ATP levels[57,58], reduced translation levels[59], and higher levels of the metabolite alarmone (p)ppGpp [53] relative to the rest of the population. Proteomic and targeted metabolite analyses of persisters support this concept and further suggest these traits are self-reinforcing, thus keeping the cell in a dormant state [55]. Second, there is heterogeneity even within cell subpopulations that survive early antibiotic killing. Higher residual metabolic capacity and ability to regrow upon antibiotic removal distinguishes true persisters from viable, but non-culturable cells (VBNC’s), which often appear intact but mostly fail to regrow [35,55,60,61]. Ribosome content, translation capacity, and ATP-dependent protein aggregation are example parameters that predict if, and how quickly, cells are able to regrow following antibiotics [35,61,62]. Finally, appreciation of the metabolic status of persisters and their heterogeneity may guide efficient use of antibiotics. Provision of specific supplemental carbon sources is capable of activating metabolism in persister cells and allowing antibiotic killing[63].

Figure 2: Metabolic Heterogeneity in Bacterial Persistence and Engineering Applications.

A. A subpopulation of bacteria cells respond to environmental stresses (e.g. starvation) by reducing metabolic activity (e.g. growth rate, [ATP], translation). Under antibiotic treatment, this subpopulation displays high phenotypic tolerance, forming persister subpopulations. Upon removal of antibiotic, persisters regrow to resemble the initial population, whereas viable-non culturable cells (VBNC) often fail to rescuscitate. B. Subpopulations of bacteria with low phenotypic productivity are often observed in metabolic engineering settings and limit overall culture yield. Metabolic engineering strategies can limit growth of low-producing cells by engineering genetic circuits which couple transcription-factor (TF) based sensing of the product to growth advantages conferred by antibiotic resistance or synthetic auxotrophy. Low producing cells (top) die or grow more slowly, whereas high producing cells (bottom) are rewarded with superior growth and survival. This results in enrichment of high-producing cells and enhanced population-level yield (right).

A second area where understanding and harnessing metabolic heterogeneity holds great potential is in metabolic engineering. Cell-to-cell variation in biosynthesis of target metabolites is often observed, and the presence of low producing subpopulations has been shown to limit overall yield[10,16,64] (Figure 2B). Consequentially, an effective method to increase ensemble yield is to control metabolic heterogeneity by minimizing low-producing cells. This can be done by using genetic circuits that sense the desired metabolite and provide high producing cells a growth advantage. These approaches demonstrated that control of metabolic heterogeneity can facilitate metabolite production in challenging large scale culture scenarios[10,64,65]. Another challenge in metabolic engineering lies in maintaining constant expression of genes in metabolic pathways of interest, which can vary widely among cells and interfere with production goals[66]. A recent study showed that by engineering a noncoherent feedforward loop into a promoter of interest, identical expression could be maintained despite genomic mutations, changes in copy number, or changes in environment[67]. Use of this type of expression system could prove useful to homogenize production across cells.

Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Here, we have discussed key advances in understanding the biological origins of metabolic heterogeneity, approaches for its measurement, and its relevance in crucial applied settings. As interrogation of metabolic phenotypes at the single cell level becomes more routine, it is likely that the overall relevance of the discussed molecular mechanisms giving rise to metabolic heterogeneity across many settings will be clarified and perhaps reveal new possibilities. Finally, we anticipate these fundamental findings to continue to be applied towards new understanding of infectious disease, metabolic engineering, and beyond.

Highlights.

Molecular noise, feedback, and asymmetric partitioning create metabolic heterogeneity.

Biosensors, mass spectrometry, and Raman spectroscopy enable single cell measurement.

Minimizing heterogeneity improves ensemble yield in engineered production strains.

Metabolic heterogeneity underlies bacterial persistence.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R35GM133797. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Martins BMC, Locke JCW: Microbial individuality: how single-cell heterogeneity enables population level strategies. Curr Opin Microbiol 2015, 24:104–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ackermann M: A functional perspective on phenotypic heterogeneity in microorganisms. Nat Rev Microbiol 2015, 13:497–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vasdekis AE, Stephanopoulos G: Review of methods to probe single cell metabolism and bioenergetics. Metab Eng 2015, 27:115–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang T, Dunlop MJ: Controlling and exploiting cell-to-cell variation in metabolic engineering. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2019, 57:10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmitz AC, Hartline CJ, Zhang F: Engineering Microbial Metabolite Dynamics and Heterogeneity. Biotechnol J 2017, 12:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palmer AC, Kishony R: Understanding, predicting and manipulating the genotypic evolution of antibiotic resistance. Nat Rev Genet 2013, 14:243–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lara AR, Galindo E, Ramírez OT, Palomares LA: Living with heterogeneities in bioreactors: Understanding the effects of environmental gradients on cells. Mol Biotechnol 2006, 34:355–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kotte O, Volkmer B, Radzikowski JL, Heinemann M: Phenotypic bistability in Escherichia coli ’ s central carbon metabolism. Mol Syst Biol 2014, 10:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solopova A, Van Gestel J, Weissing FJ, Bachmann H, Teusink B, Kok J, Kuipers OP: Bet-hedging during bacterial diauxic shift. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111:7427–7432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao Y, Bowen CH, Liu D, Zhang F: Exploiting nongenetic cell-to-cell variation for enhanced biosynthesis. Nat Chem Biol 2016, 12:339–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vilhena C, Kaganovitch E, Shin JY, Grunberger A, Behr S, Kristoficova I, Brameyer S, Kohlheyer D, Jung K: A Single-Cell View of the BtsSR/YpdAB Pyruvate Sensing Network in Escherichia coli and its Biological Relevance. J Bacteriol 2018, 200:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yaginuma H, Kawai S, Tabata K V., Tomiyama K, Kakizuka A, Komatsuzaki T, Noji H, Imamura H: Diversity in ATP concentrations in a single bacterial cell population revealed by quantitative single-cell imaging. Sci Rep 2014, 4:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Failmezger J, Ludwig J, Nieß A, Siemann-Herzberg M: Quantifying ribosome dynamics in Escherichia coli using fluorescence. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2017, 364:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chai Q, Singh B, Peisker K, Metzendorf N, Ge X, Dasgupta S, Sanyal S: Organization of ribosomes and nucleoids in escherichia coli cells during growth and in quiescence. J Biol Chem 2014, 289:11342–11352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bakshi S, Siryaporn A, Goulian M, Weisshaar JC: Superresolution imaging of ribosomes and RNA polymerase in live Escherichia coli cells. 2012, 85:21–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mustafi N, Grünberger A, Kohlheyer D, Bott M, Frunzke J: The development and application of a single-cell biosensor for the detection of l-methionine and branched-chain amino acids. Metab Eng 2012, 14:449–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Binder D, Drepper T, Jaeger KE, Delvigne F, Wiechert W, Kohlheyer D, Grünberger A: Homogenizing bacterial cell factories: Analysis and engineering of phenotypic heterogeneity. Metab Eng 2017, 42:145–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boulineau S, Tostevin F, Kiviet DJ, Rein P, Nghe P, Tans SJ: Single-Cell Dynamics Reveals Sustained Growth during Diauxic Shifts. PLoS One 2013, 8:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schreiber F, Littmann S, Lavik G, Escrig S, Meibom A, Kuypers MMM, Ackermann M: Phenotypic heterogeneity driven by nutrient limitation promotes growth in fluctuating environments. Nat Microbiol 2016, 1:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tonn MK, Thomas P, Barahona M, Oyarzún DA: Stochastic modelling reveals mechanisms of metabolic heterogeneity. Commun Biol 2019, 2:1–9.(••)Stochastic modeling approaches using experimentally determined metabolic enzyme expression and kinetics predict product metabolite heterogeneity is pervasive in E. coli.

- 21.Taniguchi Y, Choi PJ, Li G, Chen H, Babu M, Hearn J, Emili A, Xie XS: Quantifying E. coli Proteome and Transcriptome with Single-Molecule Sensitivity in Single Cells. Science 2010, 329:533–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang S, Kim S, Rim Lim Y, Kim C, An HJ, Kim JH, Sung J, Lee NK: Contribution of RNA polymerase concentration variation to protein expression noise. Nat Commun 2014, 5:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silander OK, Nikolic N, Zaslaver A, Bren A, Kikoin I, Alon U, Ackermann M: A genome-wide analysis of promoter-mediated phenotypic noise in Escherichia coli. PLoS Genet 2012, 8:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.To T-L, Maheshri N: Noise Can Induce Bimodality in Positive Transcriptional Feedback Loops Without Bistability. Science 2010, 1:1142–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guantes R, Benedetti I, Silva-Rocha R, De Lorenzo V: Transcription factor levels enable metabolic diversification of single cells of environmental bacteria. ISME J 2016, 10:1122–1133.(•) Demonstrates how noise and regulation of a low copy number transcription factor (XylR) lead to bimodal diversification in xylene metabolism.

- 26.Choi PJ, Cai L, Frieda K, Xie XS: A stochastic Single-Molecule Event Triggers Phenotype Switch of a Bacterial Cell. Science 2008, 322:442–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Heerden JH, Wortel MT, Bruggeman FJ, Heijnen JJ, Bollen YJM, Planqué R, Hulshof J, O’Toole TG, Wahl SA, Teusink B: Lost in transition: Start-up of glycolysis yields subpopulations of nongrowing cells. Science 2014, 343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huh D, Paulsson J: Non-genetic heterogeneity from stochastic partitioning at cell division. Nat Genet 2011, 43:95–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soltani M, Vargas-Garcia CA, Antunes D, Singh A: Intercellular Variability in Protein Levels from Stochastic Expression and Noisy Cell Cycle Processes. PLoS Comput Biol 2016, 12:1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landgraf D, Okumus B, Chien P, Baker TA, Paulsson J: Segregation of molecules at cell division reveals native protein localization. Nat Methods 2012, 9:480–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bennett BD, Kimball EH, Gao M, Osterhout R, Van Dien SJ, Rabinowitz JD: Absolute metabolite concentrations and implied enzyme active site occupancy in Escherichia coli. Nat Chem Biol 2009, 5:593–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kiviet DJ, Nghe P, Walker N, Boulineau S, Sunderlikova V, Tans SJ: Stochasticity of metabolism and growth at the single-cell level. Nature 2014, 514:376–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu D, Zhang F: Metabolic Feedback Circuits Provide Rapid Control of Metabolite Dynamics. ACS Synth Biol 2018, 7:347–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vedel S, Nunns H, Košmrlj A, Semsey S, Trusina A: Asymmetric Damage Segregation Constitutes an Emergent Population-Level Stress Response. Cell Syst. 2016, 3:187–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pu Y, Li Y, Jin X, Tian T, Ma Q, Zhao Z, Lin S yuan, Chen Z, Li B, Yao G, et al. : ATP-Dependent Dynamic Protein Aggregation Regulates Bacterial Dormancy Depth Critical for Antibiotic Tolerance. Mol Cell 2019, 73:143–156.e4. (••) This study interrogated the importance of ATP levels and dynamic protein aggregation in bacterial persister formation and post-antibiotic rescuscitation, and also refined the distinction between VBNC and persisters.

- 36.Liu D, Evans T, Zhang F: Applications and advances of metabolite biosensors for metabolic engineering. Metab Eng 2015, 31:35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paige JS, Nguyen-Duc T, Song W, Jaffrey SR: Fluorescence imaging of cellular metabolites with RNA. Science 2012, 335:1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Filonov GS, Moon JD, Svensen N, Jaffrey SR: Broccoli: Rapid selection of an RNA mimic of green fluorescent protein by fluorescence-based selection and directed evolution. J Am Chem Soc 2014, 136:16299–16308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Warner KD, Sjekloa L, Song W, Filonov GS, Jaffrey SR, Ferré-D’Amaré AR: A homodimer interface without base pairs in an RNA mimic of red fluorescent protein. Nat Chem Biol 2017, 13:1195–1201.(•) A fluorescent RNA aptamer analogous to RFP has less toxicity, reduced photobleaching, and reduced background fluorescence. This further improves the utility of RNA aptamers for metabolite biosensing in heterogeneity studies.

- 40.Xiao Y, Jiang W, Zhang F: Developing a Genetically Encoded, Cross-Species Biosensor for Detecting Ammonium and Regulating Biosynthesis of Cyanophycin. ACS Synth Biol 2017, 6:1807–1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mannan AA, Liu D, Zhang F, Oyarzún DA: Fundamental Design Principles for Transcription-Factor-Based Metabolite Biosensors. ACS Synth Biol 2017, 6:1851–1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.You M, Litke JL, Jaffrey SR: Imaging metabolite dynamics in living cells using a Spinach-based riboswitch. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112:E2756–E2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheik AR, Muller EEL, Audinot JN, Lebrun LA, Grysan P, Guignard C, Wilmes P: In situ phenotypic heterogeneity among single cells of the filamentous bacterium Candidatus Microthrix parvicella. ISME J 2016, 10:1274–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zimmermann M, Escrig S, Hübschmann T, Kirf MK, Brand A, Inglis RF, Musat N, Müller S, Meibom A, Ackermann M, et al. : Phenotypic heterogeneity in metabolic traits among single cells of a rare bacterial species in its natural environment quantified with a combination of flow cell sorting and NanoSIMS. Front Microbiol 2015, 6:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nikolic N, Schreiber F, Dal Co A, Kiviet DJ, Bergmiller T, Littmann S, Kuypers MMM, Ackermann M: Cell-to-cell variation and specialization in sugar metabolism in clonal bacterial populations. PLoS Genet 2017, 13:1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olaniyi OO, Yang K, Zhu Y-G, Cui L: Heavy water-labeled Raman spectroscopy reveals carboxymethylcellulose-degrading bacteria and degradation activity at the single-cell level. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2019, 103:1455–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumar VBN, Guo S, Bocklitz T, Rösch P, Popp J: Demonstration of Carbon Catabolite Repression in Naphthalene Degrading Soil Bacteria via Raman Spectroscopy Based Stable Isotope Probing. Anal Chem 2016, 88:7574–7582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Premasiri WR, Lee JC, Sauer-Budge A, Théberge R, Costello CE, Ziegler LD: The biochemical origins of the surface-enhanced Raman spectra of bacteria: a metabolomics profiling by SERS. Anal Bioanal Chem 2016, 408:4631–4647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kobayashi-Kirschvink KJ, Nakaoka H, Oda A, Kamei K ichiro F, Nosho K, Fukushima H, Kanesaki Y, Yajima S, Masaki H, Ohta K, et al. : Linear Regression Links Transcriptomic Data and Cellular Raman Spectra. Cell Syst 2018, 7:104–117.(•) Bulk Raman spectra and transcriptomes across multiple conditions were cross correlated to increase the utility and discriminative capacity of single cell Raman Spectra in bacterial populations.

- 50.Balaban NQ, Helaine S, Lewis K, Ackermann M, Aldridge B, Andersson DI, Brynildsen MP, Bumann D, Camilli A, Collins JJ, et al. : Definitions and guidelines for research on antibiotic persistence. Nat Rev Microbiol 2019, 17:441–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.El Meouche I, Dunlop MJ: Heterogeneity in efflux pump expression predisposes antibiotic-resistant cells to mutation. Science 2018, 362:686–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Luidalepp H, Jõers A, Kaldalu N, Tenson T: Age of inoculum strongly influences persister frequency and can mask effects of mutations implicated in altered persistence. J Bacteriol 2011, 193:3598–3605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Amato SM, Brynildsen MP: Persister heterogeneity arising from a single metabolic stress. Curr Biol 2015, 25:2090–2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dal Co A, Ackermann M, van Vliet S: Metabolic activity affects the response of single cells to a nutrient switch in structured populations. J R Soc Interface 2019, 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Radzikowski JL, Vedelaar S, Siegel D, Ortega ÁD, Schmidt A, Heinemann M: Bacterial persistence is an active σ S stress response to metabolic flux limitation . Mol Syst Biol 2016, 12:882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pontes MH, Groisman EA: Slow growth determines nonheritable antibiotic resistance in Salmonella enterica . Sci Signal 2019, 12:eaax3938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zalis EA, Nuxoll AS, Manuse S, Clair G, Radlinski LC, Conlon BP, Adkins J, Lewis K: Stochastic Variation in Expression of the Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle Produces Persister Cells. MBio 2019, 10:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Conlon BP, Rowe SE, Gandt AB, Nuxoll AS, Donegan NP, Zalis EA, Clair G, Adkins JN, Cheung AL, Lewis K: Persister formation in Staphylococcus aureus is associated with ATP depletion. Nat Microbiol 2016, 1:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cho J, Rogers J, Kearns M, Leslie M, Hartson SD, Wilson KS: Escherichia coli persister cells suppress translation by selectively disassembling and degrading their ribosomes. Mol Microbiol 2015, 95:352–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aryapetyan M, Williams T, Oliver JD: Relationship between the Viable but Nonculturable State and Antibiotic Persister Cells. J Bacteriol 2018, 200:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim JS, Chowdhury N, Yamasaki R, Wood TK: Viable but non-culturable and persistence describe the same bacterial stress state. Environ Microbiol 2018, 20:2038–2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim JS, Yamasaki R, Song S, Zhang W, Wood TK: Single cell observations show persister cells wake based on ribosome content. Environ Microbiol 2018, 20:2085–2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Allison KR, Brynildsen MP, Collins JJ: Metabolite-enabled eradication of bacterial persisters by aminoglycosides. Nature 2011, 473:216–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rugbjerg P, Myling-Petersen N, Porse A, Sarup-Lytzen K, Sommer MOA: Diverse genetic error modes constrain large-scale bio-based production. Nat Commun 2018, 9:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rugbjerg P, Sarup-Lytzen K, Nagy M, Sommer MOA: Synthetic addiction extends the productive life time of engineered Escherichia coli populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115:2347–2352.(•)Characterizes the growth advantage of phenotypic low-producing cells in a bioreactor setting and further emergence of genotypic low-producing variants. Synthetic addiction strategies are used to homogenize and improve production in long term culture.

- 66.Münch KM, Müller J, Wienecke S, Bergmann S, Heyber S, Biedendieck R, Münch R, Jahn D: Polar fixation of plasmids during recombinant protein production in Bacillus megaterium results in population heterogeneity. Appl Environ Microbiol 2015, 81:5976–5986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Segall-Shapiro TH, Sontag ED, Voigt CA: Engineered promoters enable constant gene expression at any copy number in bacteria. Nat Biotechnol 2018, 36:352–358.(••)Incoherent feedforward regulation is engineered into promoters, generating consistent gene expression despite changes in copy number or environment. This is a novel metabolic engineering strategy to minimize heterogeneity in pathway enzyme expression.