Abstract

Background

The Bayesian penalized likelihood (BPL) algorithm Q.Clear (GE Healthcare) allows fully convergent iterative reconstruction that results in better image quality and quantitative accuracy, while limiting image noise. The present study aimed to optimize BPL reconstruction parameters for 18F-NaF PET/CT images and to determine the feasibility of 18F-NaF PET/CT image acquisition over shorter durations in clinical practice.

Methods

A custom-designed thoracic spine phantom consisting of several inserts, soft tissue, normal spine, and metastatic bone tumor, was scanned using a Discovery MI PET/CT scanner (GE Healthcare). The phantom allows optional adjustment of activity distribution, tumor size, and attenuation. We reconstructed PET images using OSEM + PSF + TOF (2 iterations, 17 subsets, and a 4-mm Gaussian filter), BPL + TOF (β = 200 to 700), and scan durations of 30–120 s. Signal-to-noise ratios (SNR), contrast, and coefficients of variance (CV) as image quality indicators were calculated, whereas the quantitative measures were recovery coefficients (RC) and RC linearity over a range of activity. We retrospectively analyzed images from five persons without bone metastases (male, n = 1; female, n = 4), then standardized uptake values (SUV), CV, and SNR at the 4th, 5th, and 6th thoracic vertebra were calculated in BPL + TOF (β = 400) images.

Results

The optimal reconstruction parameter of the BPL was β = 400 when images were acquired at 120 s/bed. At 90 s/bed, the BPL with a β value of 400 yielded 24% and 18% higher SNR and contrast, respectively, than OSEM (2 iterations; 120 s acquisitions). The BPL was superior to OSEM in terms of RC and the RC linearity over a range of activity, regardless of scan duration. The SUVmax were lower in BPL, than in OSEM. The CV and vertebral SNR in BPL were superior to those in OSEM.

Conclusions

The optimal reconstruction parameters of 18F-NaF PET/CT images acquired over different durations were determined. The BPL can reduce PET acquisition to 90 s/bed in 18F-NaF PET/CT imaging. Our results suggest that BPL (β = 400) on SiPM-based TOF PET/CT scanner maintained high image quality and quantitative accuracy even for shorter acquisition durations.

Keywords: Q.Clear, Quantitation, 18F-NaF, SiPM, BPL, TOF

Introduction

Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) with 18F-sodium fluoride (18F-NaF) is clinically applied to detect bone metastases derived from a wide range of primary tumors [1–3]. 18F-NaF PET/CT is more sensitive, specific, and diagnostically accurate than traditional bone planar imaging and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) using 99mTc-labeled phosphate compounds [4, 5]. Responses to therapy for bone metastases can also be assessed by 18F-NaF PET/CT using quantitative indices such as standardized uptake values (SUV) [6]. However, prolonged acquisition > 30 min can be uncomfortable for patients with bone metastatic pain, and risk of patient motion is increased; thus, more rapid 18F-NaF PET/CT image acquisition is needed [7, 8].

The Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI) and the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM) [4, 9] practice guidelines for 18F-NaF PET/CT imaging recommend that the 18F-NaF PET/CT tumor imaging protocol should be identical to that of 18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (18F-FDG) PET/CT. However, optimum image acquisition and reconstruction parameters in terms of 18F-NaF PET/CT imaging have not been described in detail. The reconstruction parameters of 18F-NaF PET/CT should be optimized for rapid image acquisition because image quality and quantitative accuracy depend on the amount and type of injected radiotracer activity and image reconstruction.

The software for image reconstruction and the hardware (detector material and design) have been upgraded in contemporary PET systems to improve image quality and quantitation [10, 11]. The Bayesian penalized likelihood reconstruction (BPL) algorithm, Q.Clear® (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA), has recently been clinically applied. The BPL runs to full convergence of image accuracy while suppressing image noise using a penalty function. It also includes point spread function (PSF) modeling and controls image noise through a penalization factor (β value), which determines the global strength of regularization [12]. Compared with conventional ordered-subset expectation maximization (OSEM) reconstruction, BPL offers a higher signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and more accurate quantitation over shorter acquisition durations [13]. Silicon photomultipliers (SiPMs) have recently replaced photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) which have led to PET detectors with smaller crystals, better timing resolution, and higher photon-detection efficiency [10, 14]. GE Healthcare introduced the first SiPM-based PET/CT scanner (Discovery MI; DMI; GE Healthcare), and it has delivered better sensitivity and high time-of-flight (TOF) performance gain. The higher sensitivity and peak noise equivalent count rate (NECR) of the DMI delivered the same SNR within ~ 40% shorter acquisition duration, compared with conventional PMT-based PET/CT scanners such as the Discovery 690 (GE Healthcare) [11].

The optimal β value in BPL should be determined by balancing contrast recovery and image noise [13]. Lindström et al. concluded that a β value of 400 for 18F-FDG whole body scans would be optimal when using BPL on a SiPM-based TOF PET/CT scanner [15]. However, acquisitions over a 3-min/bed position applied in their study can be clinically problematic for total-body 18F-NaF PET/CT image acquisition from the vertex to the toes in terms of patient comfort and throughput [16]. De Bernardi et al. used a regularized reconstruction similar to BPL to reduce the acquisition duration by about one-third [7], whereas Sonni et al. stated that DMI reduced PET imaging acquisition to 90 s/bed [17]. Furthermore, Lindström et al. showed that the acquisition durations could be reduced from 3 to 2 min/bed when BPL was used instead of OSEM on the DMI scanner [15]. Therefore, we postulated that BPL on the SiPM-based PET/CT scanner can reduce the amount of time required for 18F-NaF PET/CT acquisition, while maintaining image quality and quantitative accuracy. The present study aimed to optimize the image reconstruction parameters of BPL in 18F-NaF PET/CT imaging using a custom-designed phantom simulating a patient with bone metastases and to determine the feasibility of decreasing the duration of 18F-NaF PET/CT image acquisition in clinical practice.

Materials and methods

PET/CT scanner

All PET data were acquired using the DMI PET/CT system with a PET scanner comprising four rings of detector blocks with LYSO crystals coupled to a SiPM array. The LYSO scintillator (LightBurst digital detector) unit includes 19,584 LYSO 3.95 × 5.3 × 25-mm crystals in a 4 × 9 matrix. The scanner has 36 detector units per ring and 9792 SiPM channels. The PET detector has axial and transaxial fields of view (FOV) of 20 and 70 cm, respectively. The timing resolution is 375 ps. The spatial resolution, sensitivity, and observed peak NECR of the scanner according to NEMA NU 2-2007 is 3.91 mm in full width at half maximum (FWHM) at 10 mm off center, 12.62 cps/kBq, and 185.6 kcps at 22.5 kBq/mL, respectively [10]. The PET system is combined with a 64-slice CT. The CT data are used for attenuation correction.

Phantom design

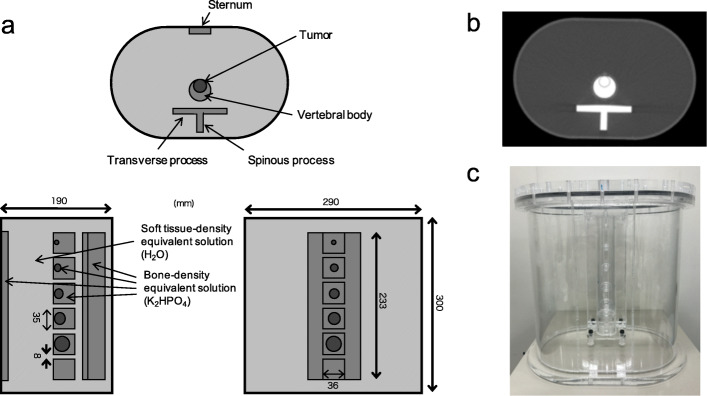

A custom-designed thoracic spine phantom (Fig. 1) comprised the trunk of a body phantom with a sternum, soft tissue, normal spine, and simulated bone tumors with diameters of 10, 13, 17, 22, and 28 mm. The main body phantom was elliptical with major and minor axes of 290 and 190 mm, respectively, and a height of 300 mm, which simulated a standard Japanese person weighing 60 kg. The vertebral body, tumor, and normal spine of the phantom contained a solution of dipotassium hydrogen phosphate (K2HPO4) with a density equivalent to that of bone. When K2HPO4 (100 g) is dissolved in 67 g of water as suggested by de Dreuille et al. [18], the composition of the K2HPO4 solution is 26% (K), 10% (P), 56% (O), and 8% (H) which is comparable to that of cranial bone: 17.6% (Ca), 8.1% (P), 43.5% (O), 5% (H), 21.2% (C), and 4% (N). The density of this K2HPO4 solution was 1.68 g/cm3 which is close to that of bone (1.61 g/cm3) [18]. The phantom allows optional adjustment of the activity distribution, tumor size, and linear attenuation coefficient (cm−1); thus, scatter and photon attenuation due to bone are considered [19]. A previous study found that the attenuation coefficient of K2HPO4 solution for 511 keV photons was 0.206 cm−1 [20].

Fig. 1.

Custom-made thoracic spine phantom. Simplified schema (a), CT image (b), and photograph (c) of phantom. Example of setup shows vertebral body phantoms with tumors of 10, 13, 17, 22, and 28 mm in diameter. Vertebral body phantom without tumors is at the bottle. Vertebral body, tumor, processus, and sternum contain K2HPO4 solution with density equivalent to that of bone and 18F-NaF. Elliptical body phantom contained 18F-NaF

All phantom experiments were conducted twice using spheres with different diameters and activity concentrations as follows. In the first round of experiments, the phantom consisted of spheres with diameters of 10, 13, 17, 22, and 28 mm containing a solution of 18F-NaF. The activity concentrations (AC) in the soft tissue, normal spine, and simulated tumor were 2.6, 15.6, and 62.4 kBq/mL, respectively, that is, tumor-to-normal bone ratio (TNR) of 4 [21–23]. In the second round of experiments, five spheres with diameters of 13 mm were set at TNR of 1, 2, 4, 8, and 16 at the normal spine activity concentration of 15.6 kBq/mL [24].

Data acquisition and image reconstruction

All emission data were acquired in three-dimensional (3D) list mode. Subsequently, PET images acquired from 30 to 120 (30, 45, 60, 90, and 120) s/bed were reconstructed using OSEM + PSF + TOF (VPFX-S) and BPL + TOF (Q.Clear + TOF, QCFX-S). We applied two iterations, 17 subsets and a 4-mm Gaussian filter to OSEM, whereas the β value in BPL varied from 200 to 700 at intervals of 100. The FOV was 50 cm and the matrix was 256 × 256 (pixel size 1.95 × 1.95 mm2, slice thickness 2.79 mm).

Data analysis

Phantom PET images were analyzed using OsiriX MD software ver.10.0.5 (Pixmeo Sàrl, Bernex, Switzerland). We placed 80% circular regions of interest (ROI) on a slice of the center tumor region, a slice of the normal bone center, and slices ± 1 and ± 2 slices from the central slice. We then calculated the SNR, contrast of a 10- or 13-mm hot sphere, and coefficients of variance (CV) as indicators of image quality. The SNR10 and 13 mm was calculated as [25] follows:

where AC10 and 13 mm hot_max was the maximum measured activity concentration in the 10- and 13-mm hot sphere ROI, ACbone_mean was the mean measured activity concentration in the normal bone ROI, and SDbone was the standard deviation of the activity concentration in normal bone ROIs. The contrast of the 10-mm hot sphere and CV were respectively calculated as [25] follows:

and

We calculated the absolute recovery coefficients (RC) and the RC linearity over a range of activity as indicators of quantitation. The RC was calculated as follows:

where AChot_mean was the mean measured activity concentration in each sphere. The True AC was measured using a BeWell Model-QS03 F/B well counter (Molecular Imaging Lab, Suita, Japan) and considered as a reference. The absolute error of the well counter determined using a National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)-traceable, rod-shaped 68Ge/68Ga source was − 0.77% in this study [26]. The PET scanner was cross-calibrated to the dose calibrator or the well counter using 18F solution according to the vendor’s recommended procedures. The RC linearity over a range of activity for OSEM and BPL was evaluated as the relationship between AChot_mean and True AC.

Clinical study

The present study proceeded in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Ethics Committee at the TMIG (Approval Nos. 250413 and 28077). All applicants provided written informed consent to participate in the study after physicians explained the study in detail. We acquired images from five persons (male, n = 1; female, n = 4; median age, 81 years; range, 77–85; average weight, 58.8 ± 9.9 kg; 52–68 kg) using DMI PET/CT scanners (GE Healthcare). The absence of bone metastases on 18F-NaF PET images was confirmed in all of them. We acquired PET/CT images at 45 min after injecting an average of 232.8 ± 34.8 (192–258) MBq of 18F-NaF. The scan duration per bed position (determined in phantom studies) was 90 s, and patients were scanned in 13 or 14 bed positions. All PET images were reconstructed under the following conditions: OSEM + PSF + TOF (2 iterations, 17 subsets, and a 4-mm Gaussian filter) and BPL + TOF (β = 400). Optimal reconstruction parameters were determined from phantom studies.

The quantitative performance and noise characteristics of the clinical PET image were analyzed at the level of the 4th, 5th, and 6th thoracic vertebrae. We adjusted and placed a sphere ROI of 80% size on the center of the axial slice in the section after measuring the ROI of the vertebral body guided by the CT boundaries of the fused PET/CT images. The mean and maximum standardized uptake values (SUVmean and SUVmax, respectively), CV and vertebral SNR of target thoracic vertebrae were calculated. The CV was defined as the standard deviation (SD) normalized to the SUVmean of the ROI placed in the vertebral body. The vertebral SNR was calculated as SUVmean in the vertebral body divided by the CV. The data were analyzed using PETSTAT software (AdIn Research, Tokyo, Japan).

Results

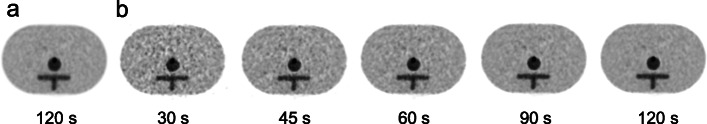

Figure 2 shows representative axial images acquired over various acquisition durations in the phantom study. A shorter acquisition time caused increased background noise. The 13-mm hot sphere was clearly recognized in BPL with an acquisition duration of ≥ 90 s, which was comparable to that in OSEM with 120 s. The SNRs of a 13-mm hot sphere (SNR13mm) in BPL with 90 s and OSEM with 120 s were 35.5 and 35.3, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Sample PET images acquired from a 13-mm sphere with different acquisition durations and reconstructed using OSEM (2 iterations) (a) and BPL (β value, 400) (b)

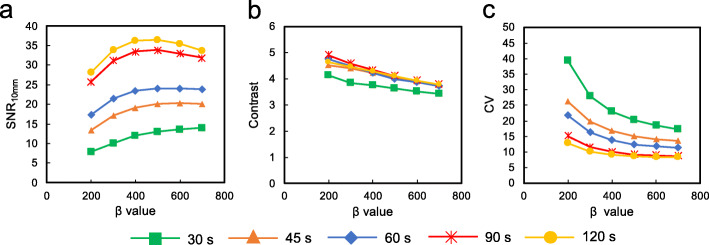

Figure 3 shows the SNR10 mm, contrast, and CV of 10-mm spheres as a function of the β value for each duration. The SNR10 mm was maximal at β values of 400–500 and subsequently decreased as β values increased. As the β value increased, the contrast and CV decreased. The SNR10 mm increased with increasing β values from 200 to 400 or 700 depending on the acquisition duration. The SNR10mm and noise characteristics also improved with increasing acquisition duration for a given β value. The contrast was independent of acquisition duration at ≥ 45 s/bed.

Fig. 3.

PET image quality of 10-mm spheres as a function of β value (range 200–700) for each acquisition duration using BPL. a SNR10mm. b Contrast. c CV

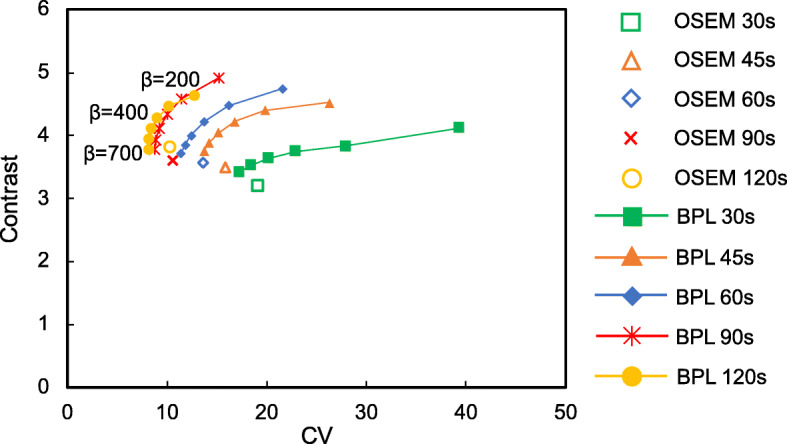

Figure 4 shows the relationship between contrast and CV for OSEM and BPL. Contrast is plotted as a function of the CV for hot spheres with diameters of 10 mm, and each plot corresponds to iterations of 2 and β values ranging from 200 to 700 in OSEM and BPL, respectively. As the value of β increased, contrast and CV decreased during all acquisitions. Therefore, a choice is needed between increased contrast and decreased CV. Ideally these points on lie in the top left of the graph [12]. The balance between contrast and CV was optimal at a β value of 400 for BPL. The contrast of BPL was superior to that of OSEM at comparable noise levels. Based on these results, we recommend a β value of 400 for BPL. The BPL (β value, 400) during 90-s acquisitions yielded similar noise levels to those obtained with OSEM (2 iterations) during 120-s acquisitions. The BPL with a β value of 400 improved SNR and contrast by 24% and 18%, respectively, compared with OSEM.

Fig. 4.

Relationship between contrast and CV curves of hot spheres with 10-mm diameter using OSEM and BPL reconstructions after each acquisition duration. Plots of OSEM correspond to 2 iterations. Curves for BPL run from left to right with decreasing β values, respectively. Unfilled and filled symbols represent OSEM and BPL, respectively

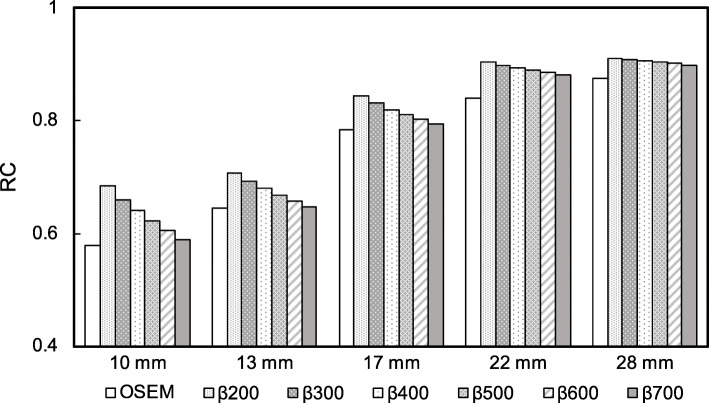

Figure 5 shows the RC for OSEM (2 iterations) and BPL (β values, 200–700) for each sphere size. The RC for OSEM decreased at smaller sphere diameter. The RC for BPL were superior to those for OSEM. The RCs decreased with increasing β values for all sphere sizes, just more significantly for the smaller sphere sizes.

Fig. 5.

Recovery coefficient as a function of sphere size with different methods of reconstructing images acquired over 120 s

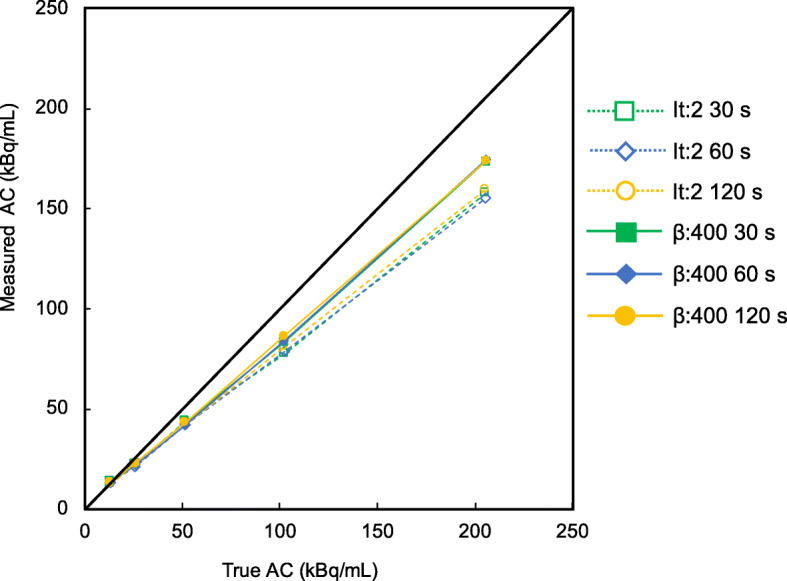

Figure 6 shows the RC linearity over a range of activity for OSEM (iteration, 2) and BPL (β values, 400) of images acquired during different acquisition durations. The BPL was more linear than OSEM because values measured using BPL were closer to the true values. Linearity for OSEM slightly varied and was better for images acquired over longer durations, whereas BPL was independent of the acquisition duration.

Fig. 6.

Correlation between true and measured activity concentrations. The RC linearity over a range of activity was measured using five spheres with diameters of 13 mm containing TNR of 1, 2, 4, 8, and 16 at the normal spine activity concentration of 15.6 kBq/mL. Unfilled symbols and dotted lines, OSEM; filled symbols and solid line, BPL. AC, activity concentration

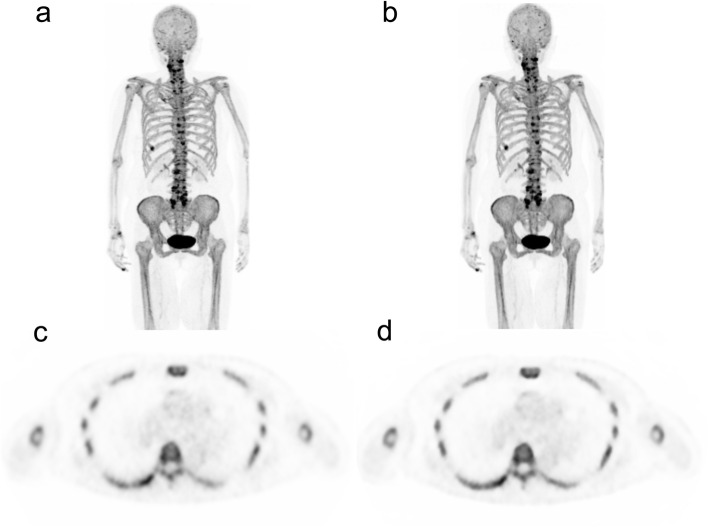

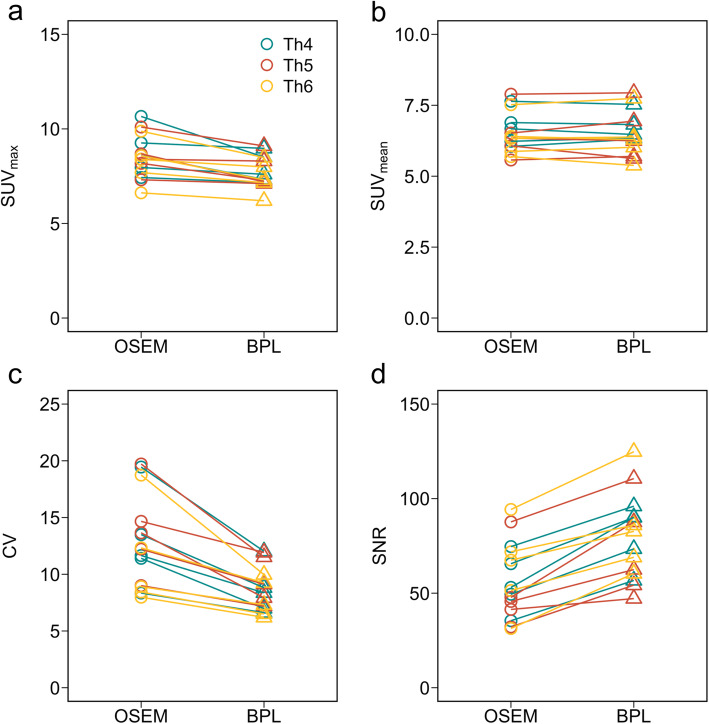

Figure 7 shows whole-body maximum intensity projection (MIP) and axial PET images acquired using DMI with OSEM and BPL reconstruction in the clinical study. The axial PET images exhibited slightly more uptake edge preservation and noise suppression in the vertebral body when reconstructed using BPL. Figure 8 shows the results of SUVmax, SUVmean, CV, and vertebral SNR of five persons under optimal reconstruction conditions (OSEM: iterations, 2; BPL: β value, 400). The SUVmax were lower in BPL than in OSEM. The noise characteristics and vertebral SNR in BPL were superior to those of OSEM.

Fig. 7.

18F-NaF PET images of a 77-year-old female (weight 63 kg). Maximum intensity projection (MIP) and axial PET images reconstructed by a, c OSEM (2 iterations) and b, d BPL (β value, 400), respectively. The hotspots of osteoblastic activity in MIP images (a, b) show the degenerative bone changes and bone bruises

Fig. 8.

Clinical comparisons of a SUVmax, b SUVmean, c CV, and d vertebral SNR under optimal reconstruction conditions (OSEM, 2 iterations; BPL, β value, 400)

Discussion

We evaluated the image quality and quantitative accuracy of BPL for reconstructing images acquired using a SiPM-based PET/CT scanner and a custom-designed phantom containing 18F-NaF and a bone-equivalent solution of K2HPO4. We found that BPL on the DMI improved SNR10mm, contrast, noise characteristics, and quantitation compared to OSEM, even though the images were acquired over a duration of 90, instead of 120 s.

The optimum image acquisition and reconstruction parameters of 18F-FDG and 18F-NaF PET/CT imaging has been considered to be identical [4, 9]. However, biodistribution and lesion uptake levels of 18F-FDG and 18F-NaF are significantly different [27]. Optimal reconstruction parameters depend on the radiotracer biodistribution and lesion uptake levels [28]. Although the parameters of BPL have been optimized for various radiotracers [29–31], 18F-NaF PET/CT has not yet been evaluated. The activity concentration and linear attenuation coefficient (cm−1) can be modified in three different locations of soft tissue, normal spine, and simulated tumor in bone using our custom-designed phantom. Thus, the effects of scatter and attenuation of photons by bone for 18F-NaF PET/CT imaging can be investigated [19].

Contrast and image noise in PET images decreased as the β value increased [12, 32, 33]. The highest SNR10 mm were at β values of 400–500. A trade-off needs to be reached between the two conflicting performance parameters of high contrast and low image noise for determining an optimal β value [25, 32]. The balance of contrast and CV was optimal when a β value was 400 in the present study, in which the β value was independent of the acquisition duration at ≥ 45 s (Fig. 4). This result was comparable with previous findings of oncologic PET imaging using 18F-fluciclovine (300) [29], 68Ga-prostate-specific membrane antigen (400–550) [31], and 18F-FDG (350–400) [12, 15, 32]. Figure 4 shows that BPL achieved higher contrast and lower image noise than OSEM. The PET images for BPL were superior to those for OSEM with the optimal reconstruction parameters (2 iterations; 120 s acquisitions), even though acquisition was reduced from 120 to 90 s. This is in agreement with the studies of De Bernardi et al. [7] and Lindström et al. [15] who found that regularized reconstruction can result in reduced acquisition durations. We therefore believe that BPL can reduce PET acquisition to 90 s/bed in 18F-NaF PET/CT imaging.

The SiPM photodetectors in the DMI PET/CT scanner are characterized by excellent intrinsic timing resolution (375 ps in the DMI) and higher sensitivity [11]. The spatial localization along a line of response calculated from Δx = c × Δt/2 (Δx, spatial localization; c, light speed; Δt, timing resolution) is 5.8 cm in the DMI [34]. The TOF of DMI should obtain a good SNR even during shorter acquisitions. Moreover, sensitivity was better for DMI PET/CT than PMT-based TOF PET/CT [11]. A recent study from our group found that the DMI used herein had 68% higher sensitivity than the PMT-based TOF PET/CT (Discovery 710; GE healthcare) [10]. The major contributor to the sensitivity gain of DMI is the wider axial FOV of 20 cm. Sonni et al. reported that very good quality 18F-FDG PET images can be acquired at 90 s/bed using the DMI [17]. The most attractive advantage derived from SiPM-based PET/CT over standard PMT-based PET/CT is more rapid image acquisition for static imaging and is increased SNR in frames of a given duration for dynamic imaging. Because SiPM-based PET/CT decreases acquisition durations as a surrogate for the 18F-NaF dose, it might enable reduction of the administered 18F-NaF dose while maintaining or improving image quality [17].

The RC increased as a function of decreasing β values as well as with the increasing sphere diameter. The RC is benefited for higher spatial resolution, and Rogasch et al. reported that the spatial resolution of BPL at a lower β value was significantly better than that of OSEM [35]. We considered that the increasing RC is mainly due to the effect of the edge-preserving properties of the relative difference penalty (RDP) in BPL reconstruction at lower β values, which γ in RDP is a parameter that controls the degree of edge-preservation [36, 37]. The RC for BPL were superior to those for OSEM, particularly when spheres were smaller. Although OSEM stops after a predetermined number of iterations, resulting in an underconverged image, BPL can reach full convergence of image accuracy without sacrificing image noise [36, 38]. These characteristics of the BPL are considered to increase quantitative accuracy. In the same context, the RC linearity over a range of activity was better for BPL than for OSEM, which was independent of acquisition duration (Fig. 6). Compared with OSEM, BPL might be able to maintain the ability to quantitatively detect potential bone metastases in 18F-NaF PET/CT images acquired over shorter durations.

The noise characteristics and vertebral SNR in BPL were superior to those in OSEM (Fig. 8). Thus, the SUVmax values were lower in BPL than in OSEM. Win et al. acquired 18F-NaF PET images in TOF mode for 3 min/bed [21]. They showed that the average SUVmax in normal thoracic vertebrae was 7.36 (range 6.99–7.66). Our average SUVmax of 7.71 in BPL reconstruction at 90 s/bed was similar to their findings. The BPL becomes smoother and less noisy depending on β values. Thus, BPL improved the SNR in the background region more effectively than OSEM and was consistent with prior findings using liver SNR [39, 40]. The better image quality of BPL with a β value of 400 in the clinical study compared with OSEM, which was compatible with the findings of our custom-designed phantom. However, we identified variability of the SUV, CV, and SNR among patients with a normal spine. We considered that this resulted from a difference not only in bone metabolism among patients, but also in the physique of patients. Such variability should be expected when images are acquired from overweight patients for whom reducing the acquisition duration is usually not advised.

The present study is limited by the fact that data were generated using a phantom simulation of a clinical exam of an average-sized Japanese patient. Further studies should investigate clinical PET images of patients over a variety of patient habitus. Prolonged acquisitions are generally considered important for improving the quality of PET images acquired from overweight patients. Chilcott et al. reported that image quality is better using BPL, than OSEM reconstruction, with the greatest benefit being for the heaviest of patients [41]. Further examinations of such patients might further demonstrate the advantages of the SiPM-based PET/CT scanner with the BPL algorithm.

Conclusion

The present study determined optimal parameters for BPL reconstruction with which 18F-NaF PET/CT images acquired over different durations. Our results suggested that the high quality and quantitative accuracy of images acquired during shorter durations (90 s/bed) can be maintained better by BPL (β = 400) than by OSEM. The information obtained from the custom-designed phantom study clarifies that SiPM-based PET/CT scanners with BPL reconstruction can detect potential bone metastases in 18F-NaF PET/CT images.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr. Akira Hirayama and Mr. Hirofumi Kawakami from GE Healthcare for valuable contributions to the data collection process for this publication and Mr. Masanari Sakai for technical support with the cyclotron operation and radiosynthesis. This study was supported in part by KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (KM, No.16 K19831; KW, No.20 K16747) and from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), the Japanese Government, and an Academic Research Grant from International University of Health and Welfare.

Abbreviations

- PET/CT

Positron emission tomography/computed tomography

- 18F-NaF

18F-sodium fluoride

- SPECT

Single-photon emission computed tomography

- SUV

Standardized uptake values

- SNMMI

Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging

- EANM

European Association of Nuclear Medicine

- 18F-FDG

18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose

- BPL

Bayesian penalized likelihood reconstruction

- PSF

Point spread function

- OSEM

Ordered-subset expectation maximization

- SNR

Signal-to-noise ratio

- SiPM

Silicon photomultiplier

- PMT

Photomultiplier tubes

- TOF

Time-of-flight

- NECR

Noise equivalent count rate

- FOV

Fields of view

- FWHM

Full width at half maximum

- AC

Activity concentration

- TNR

Tumor-to-normal bone ratio

- 3D

Three-dimensional

- ROI

Regions of interest

- CV

Coefficients of variance

- RC

Recovery coefficients

- SD

Standard deviation

- MIP

Maximum intensity projection

Authors’ contributions

KM, KW, and KI designed the study. HI developed the phantom. KW, KI, and TM collected the data. MY, KS, TY, YK, and SH processed the data. TY, KM, KW, and RK interpreted the data. TY, KM, MY, and KS drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study proceeded in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee at the TMIG (Approval No. 250413 and 28077). All applicants provided written informed consent to participate in the study after physicians explained the study in detail.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Tokiya Yoshii and Kenta Miwa contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Grecchi E, O’Doherty J, Veronese M, Tsoumpas C, Cook GJ, Turkheimer FE. Multimodal partial-volume correction: application to 18F-fluoride PET/CT bone metastases studies. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:1408–1414. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.160598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kulshrestha RK, Vinjamuri S, England A, Nightingale J, Hogg P. The role of 18F-sodium fluoride PET/CT bone scans in the diagnosis of metastatic bone disease from breast and prostate cancer. J Nucl Med Technol. 2016;44:217–222. doi: 10.2967/jnmt.116.176859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evangelista L, Bertoldo F, Boccardo F, Conti G, Menchi I, Mungai F, et al. Diagnostic imaging to detect and evaluate response to therapy in bone metastases from prostate cancer: current modalities and new horizons. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43:1546–1562. doi: 10.1007/s00259-016-3350-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Segall G, Delbeke D, Stabin MG, Even-Sapir E, Fair J, Sajdak R, et al. SNM practice guideline for sodium 18F-fluoride PET/CT bone scans 1.0. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1813-1820. doi:10.2967/jnumed.110.082263. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Li Y, Schiepers C, Lake R, Dadparvar S, Berenji GR. Clinical utility of 18F-fluoride PET/CT in benign and malignant bone diseases. Bone. 2012;50:128–139. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cook G, Jr, Parker C, Chua S, Johnson B, Aksnes AK, Lewington VJ. 18F-fluoride PET: changes in uptake as a method to assess response in bone metastases from castrate-resistant prostate cancer patients treated with 223Ra-chloride (Alpharadin) EJNMMI Res. 2011;1:4. doi: 10.1186/2191-219X-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Bernardi E, Magnani P, Gianolli L, Gilardi MC, Bettinardi V. Regularized ML reconstruction for time/dose reduction in 18F-fluoride PET/CT studies. Phys Med Biol. 2015;60:67–80. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/60/1/67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray I, Chittenden SJ, Denis-Bacelar AM, Hindorf C, Parker CC, Chua S, et al. The potential of 223Ra and 18F-fluoride imaging to predict bone lesion response to treatment with 223Ra-dichloride in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017. 10.1007/s00259-017-3744-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Beheshti M, Mottaghy FM, Payche F, Behrendt FF, Van den Wyngaert T, Fogelman I, et al. 18F-NaF PET/CT: EANM procedure guidelines for bone imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42:1767–1777. doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3138-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagatsuma K, Miwa K, Sakata M, Oda K, Ono H, Kameyama M, et al. Comparison between new-generation SiPM-based and conventional PMT-based TOF-PET/CT. Phys Med. 2017;42:203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmp.2017.09.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsu DFC, Ilan E, Peterson WT, Uribe J, Lubberink M, Levin CS. Studies of a next-generation silicon-photomultiplier-based time-of-flight PET/CT system. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:1511–1518. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.189514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teoh EJ, McGowan DR, Macpherson RE, Bradley KM, Gleeson FV. Phantom and clinical evaluation of the Bayesian penalized likelihood reconstruction algorithm Q.Clear on an LYSO PET/CT system. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:1447–1452. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.159301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.te Riet J, Rijnsdorp S, Roef MJ, Arends AJ. Evaluation of a Bayesian penalized likelihood reconstruction algorithm for low-count clinical 18F-FDG PET/CT. EJNMMI Phys. 2019;6. 10.1186/s40658-019-0262-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Bisogni MG, Del Guerra A, Belcari N. Medical applications of silicon photomultipliers. Nuclear instruments and methods in physics research section A: accelerators, spectrometers, detectors and associated equipment. 2019;926:118–128. doi: 10.1016/j.nima.2018.10.175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindstrom E, Sundin A, Trampal C, Lindsjo L, Ilan E, Danfors T, et al. Evaluation of penalized-likelihood estimation reconstruction on a digital time-of-flight PET/CT scanner for 18F-FDG whole-body examinations. J Nucl Med. 2018;59:1152–1158. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.200790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurdziel KA, Shih JH, Apolo AB, Lindenberg L, Mena E, McKinney YY, et al. The kinetics and reproducibility of 18F-sodium fluoride for oncology using current PET camera technology. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:1175–1184. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.100883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sonni I, Baratto L, Park S, Hatami N, Srinivas S, Davidzon G, et al. Initial experience with a SiPM-based PET/CT scanner: influence of acquisition time on image quality. EJNMMI Phys. 2018;5. 10.1186/s40658-018-0207-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Dreuille OD, Strijckmans V, Almeida P, Loc’h C, Bendriem B. Bone equivalent liquid solution to assess accuracy of transmission measurements in SPECT and PET. 1996 IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium Conference Record; 1996. p. 1444-7 vol.2.

- 19.Ichikawa H, Miwa K, Matsutomo N, Watanabe Y, Kato T, Shimada H. Development of a novel body phantom with bone equivalent density for evaluation of bone SPECT. Nihon Hoshasen Gijutsu Gakkai Zasshi. 2015;71:1235–1240. doi: 10.6009/jjrt.2015_JSRT_71.12.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iida H, Hori Y, Ishida K, Imabayashi E, Matsuda H, Takahashi M, et al. Three-dimensional brain phantom containing bone and grey matter structures with a realistic head contour. Ann Nucl Med. 2013;27:25–36. doi: 10.1007/s12149-012-0655-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Win AZ, Aparici CM. Normal SUV values measured from NaF18- PET/CT bone scan studies. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108429. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sachpekidis C, Goldschmidt H, Hose D, Pan L, Cheng C, Kopka K, et al. PET/CT studies of multiple myeloma using 18F-FDG and 18F-NaF: comparison of distribution patterns and tracers’ pharmacokinetics. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41:1343–1353. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2721-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Etchebehere EC, Araujo JC, Fox PS, Swanston NM, Macapinlac HA, Rohren EM. Prognostic factors in patients treated with 223Ra: the role of skeletal tumor burden on baseline 18F-fluoride PET/CT in predicting overall survival. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:1177–1184. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.158626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sabbah N, Jackson T, Mosci C, Jamali M, Minamimoto R, Quon A, et al. 18F-sodium fluoride PET/CT in oncology: an atlas of SUVs. Clin Nucl Med. 2015;40:e228–e231. doi: 10.1097/rlu.0000000000000633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akamatsu G, Ishikawa K, Mitsumoto K, Taniguchi T, Ohya N, Baba S, et al. Improvement in PET/CT image quality with a combination of point-spread function and time-of-flight in relation to reconstruction parameters. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:1716–1722. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.103861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miwa K, Wagatsuma K, Iimori T, Sawada K, Kamiya T, Sakurai M, et al. Multicenter study of quantitative PET system harmonization using NIST-traceable 68Ge/68Ga cross-calibration kit. Phys Med. 2018;52:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmp.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minamimoto R, Mosci C, Jamali M, Barkhodari A, Habte F, Jackson T, et al. Semiquantitative analysis of the biodistribution of the combined 18F-NaF and 18F-FDG administration for PET/CT imaging. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:688–694. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.153767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sunderland JJ, Christian PE. Quantitative PET/CT scanner performance characterization based upon the society of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging clinical trials network oncology clinical simulator phantom. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:145–152. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.148056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teoh EJ, McGowan DR, Schuster DM, Tsakok MT, Gleeson FV, Bradley KM. Bayesian penalised likelihood reconstruction (Q.Clear) of 18F-fluciclovine PET for imaging of recurrent prostate cancer: semi-quantitative and clinical evaluation. Br J Radiol. 2018;91:20170727. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20170727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Doherty J, McGowan DR, Abreu C, Barrington S. Effect of Bayesian-penalized likelihood reconstruction on [13N]-NH3 rest perfusion quantification. J Nucl Cardiol. 2017;24:282–290. doi: 10.1007/s12350-016-0554-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ter Voert E, Muehlematter UJ, Delso G, Pizzuto DA, Muller J, Nagel HW, et al. Quantitative performance and optimal regularization parameter in block sequential regularized expectation maximization reconstructions in clinical 68Ga-PSMA PET/MR. EJNMMI Res. 2018;8:70. doi: 10.1186/s13550-018-0414-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reynes-Llompart G, Gamez-Cenzano C, Vercher-Conejero JL, Sabate-Llobera A, Calvo-Malvar N, Marti-Climent JM. Phantom, clinical, and texture indices evaluation and optimization of a penalized-likelihood image reconstruction method (Q.Clear) on a BGO PET/CT scanner. Med Phys. 2018;45:3214–3222. doi: 10.1002/mp.12986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miwa K, Wagatsuma K, Nemoto R, Masubuchi M, Kamitaka Y, Yamao T, et al. Detection of sub-centimeter lesions using digital TOF-PET/CT system combined with Bayesian penalized likelihood reconstruction algorithm. Ann Nucl Med. 2020. 10.1007/s12149-020-01500-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Surti S, Karp JS. Advances in time-of-flight PET. Phys Med. 2016;32:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmp.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rogasch JM, Suleiman S, Hofheinz F, Bluemel S, Lukas M, Amthauer H, et al. Reconstructed spatial resolution and contrast recovery with Bayesian penalized likelihood reconstruction (Q.Clear) for FDG-PET compared to time-of-flight (TOF) with point spread function (PSF) EJNMMI Phys. 2020;7:2. doi: 10.1186/s40658-020-0270-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahn S, Ross SG, Asma E, Miao J, Jin X, Cheng L, et al. Quantitative comparison of OSEM and penalized likelihood image reconstruction using relative difference penalties for clinical PET. Phys Med Biol. 2015;60:5733–5751. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/60/15/5733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wangerin KA, Ahn S, Wollenweber S, Ross SG, Kinahan PE, Manjeshwar RM. Evaluation of lesion detectability in positron emission tomography when using a convergent penalized likelihood image reconstruction method. J Med Imaging (Bellingham) 2017;4:011002. doi: 10.1117/1.JMI.4.1.011002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teoh EJ, McGowan DR, Bradley KM, Belcher E, Black E, Gleeson FV. Novel penalised likelihood reconstruction of PET in the assessment of histologically verified small pulmonary nodules. Eur Radiol. 2016;26:576–584. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-3832-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parvizi N, Franklin JM, McGowan DR, Teoh EJ, Bradley KM, Gleeson FV. Does a novel penalized likelihood reconstruction of 18F-FDG PET-CT improve signal-to-background in colorectal liver metastases? Eur J Radiol. 2015;84:1873–1878. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kurita Y, Ichikawa Y, Nakanishi T, Tomita Y, Hasegawa D, Murashima S, et al. The value of Bayesian penalized likelihood reconstruction for improving lesion conspicuity of malignant lung tumors on 18F-FDG PET/CT: comparison with ordered subset expectation maximization reconstruction incorporating time-of-flight model and point spread function correction. Annals of Nuclear Medicine. 2020;34:272–279. doi: 10.1007/s12149-020-01446-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chilcott AK, Bradley KM, McGowan DR. Effect of a Bayesian penalized likelihood PET reconstruction compared with ordered subset expectation maximization on clinical image quality over a wide range of patient weights. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2018;210:153–157. doi: 10.2214/AJR.17.18060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.