Abstract

Cyanogenic glycosides form part of a binary plant defense system that, upon catabolism, detonates a toxic hydrogen cyanide bomb. In seed plants, the initial step of cyanogenic glycoside biosynthesis—the conversion of an amino acid to the corresponding aldoxime—is catalyzed by a cytochrome P450 from the CYP79 family. An evolutionary conundrum arises, as no CYP79s have been identified in ferns, despite cyanogenic glycoside occurrence in several fern species. Here, we report that a flavin-dependent monooxygenase (fern oxime synthase; FOS1), catalyzes the first step of cyanogenic glycoside biosynthesis in two fern species (Phlebodium aureum and Pteridium aquilinum), demonstrating convergent evolution of biosynthesis across the plant kingdom. The FOS1 sequence from the two species is near identical (98%), despite diversifying 140 MYA. Recombinant FOS1 was isolated as a catalytic active dimer, and in planta, catalyzes formation of an N-hydroxylated primary amino acid; a class of metabolite not previously observed in plants.

Subject terms: Molecular biology, Evolution, Plant sciences

Thodberg et al. report the first step of the synthesis of cyanogenic glycosides, a plant defense mechanism, by a Flavin-dependent monooxygenase (FOS1) in ferns, revealing convergent evolution of biosynthesis across the plant kingdom. The authors isolate FOS1 as a catalytically active dimer and demonstrate that it catalyzes the formation of N-hydroxylated amino acids.

Introduction

Plants produce a plethora of natural products (phytochemicals or specialized metabolites) enabling interactions with their biotic and abiotic environment. Cyanogenic glycosides are one such class of amino acid-derived natural products present in more than 3000 plant species, including ferns, gymnosperms, and angiosperms1–3. For example, the cyanogenic glycosides prunasin and amygdalin are responsible for the bitterness of wild almond (Prunus dulcis)4,5. Upon tissue disruption, cyanogenic glycosides are hydrolyzed by specific β-glucosidases resulting in detonation of a hydrogen cyanide bomb as an immediate toxic chemical response e.g. towards chewing herbivores2. More recently, cyanogenic glycosides have been shown to possess alternative functions as remobilizable storage molecules of reduced nitrogen, controllers of bud break and flower induction, and as quenchers of reactive oxygen species6–9.

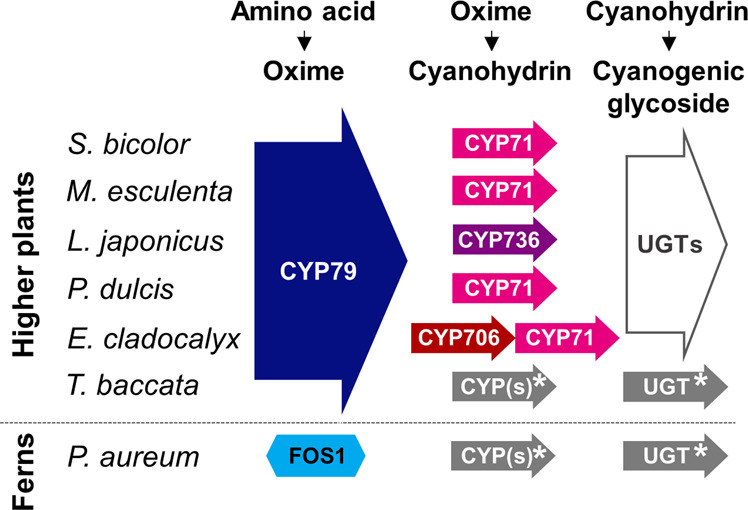

In higher plants (gymnosperms and angiosperms), the biosynthesis of cyanogenic glycosides is catalyzed by cytochromes P450 (CYPs) and UDP-glucosyltransferases (UGTs)2,10,11. In all cases, initial conversion of the parent amino acid to the corresponding E-oxime is catalyzed by a functionally conserved CYP79 family enzyme. Independently evolved CYP71, CYP706, or CYP736 enzymes convert the oxime into an α-hydroxynitrile10,12,13 that is glycosylated by a UGT85 or UGT94 family member to produce the cyanogenic mono- or diglycosides2,4,14 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. A schematic overview of the biosynthetic pathway of cyanogenic glycosides in plants.

In ferns, the conversion of the parent amino acid into an oxime is catalyzed by a multifunctional FMO, whereas in all higher seed plant species analyzed, the reaction is catalyzed by a cytochrome P450 from the CYP79 family2,4,10,12,14,61,73–79. *Uncharacterized pathway partners.

The CYP79-catalyzed reaction proceeds via two N-hydroxylations, a decarboxylation, and a dehydration reaction in a single catalytic site15–17. No other enzymes across the plant kingdom are known to catalyze the conversion of an α-amino acid into an oxime. In addition to their involvement as intermediates in cyanogenic glycoside biosynthesis, CYP79-formed oximes are important metabolites in general and specialized metabolism18 exemplified by indole-3-acetaldoxime, which is a shared precursor for the phytohormone auxin (indole-3-acetic acid, IAA), the phytoalexin camalexin and tryptophan-derived glucosinolates19–21. An evolutionary conundrum arises as no gene sequences encoding CYP79s have been found in fern transcriptomes nor genomes22,23 despite the occurrence of cyanogenic glycosides in ferns1,24. Due to their significant phylogenetic position, ferns represent an important lineage for studying the evolution of land plants. Fern research has been hampered by the scarcity of genome information22. In total, 11 orders of ferns are known of which four are extant: Psilotopsida, Equisetopsida, Marattiopsida, and Polypodiopsida25. Polypodiopsida are termed modern ferns, and ~3% of the species in this order have been reported as cyanogenic1,24,26.

Here, we investigate the cyanogenic glycoside biosynthetic pathway in modern ferns by a differentially expression survey of de novo assembled transcriptomes from Phlebodium aureum and Pteridium aquilinum. We report biochemical and biological evidence that ferns harbor an N-hydroxylating flavin-dependent monooxygenase that converts phenylalanine to a corresponding oxime via N-hydroxyphenylalanine. This demonstrates convergent evolution at the biochemical pathway level and resolves how ferns produce cyanogenic glucosides in the absence of CYP79 encoding genes.

Results

Metabolite-guided pathway discovery in ferns

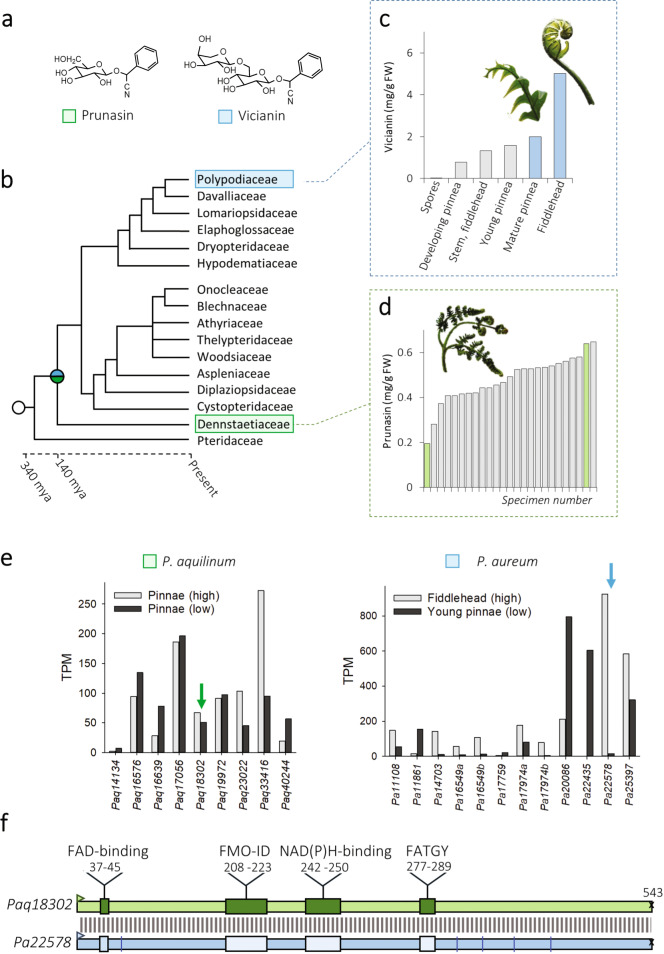

The two distantly related modern ferns, Phlebodium aureum (Polypodiaceae) and Pteridium aquilinum (Dennstaedtiaceae) (Fig. 2), produce the phenylalanine-derived cyanogenic monoglucoside prunasin (D-mandelonitrile-β-D-glucopyranoside)1,27 and the diglycoside vicianin (6-O-arabinopyranosylglucopyranoside)28, respectively. Targeted metabolite profiling of a population of 25 field-collected P. aquilinum (Paq) identified individuals with high and low cyanogenic glycoside containing pinnae ranging from 0.2 to 0.6 mg prunasin g−1 fw (Fig. 2d). Two individuals were selected based on their metabolite content and the quality of RNA extracted. Similarly, analysis of different tissues within a single Phlebodium aureum (Pa) fern identified variable levels of vicianin in the different tissue types from negligible levels in the spores, to 5 mg vicianin g−1 fw in the emerging fiddlehead (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. 1). For Pa, fiddlehead and young pinna were selected for transcriptome analysis (Fig. 2c). mRNA was isolated from these four tissues to obtain biosynthetic gene candidates using a comparative transcriptomic approach.

Fig. 2. Cyanogenic glycoside content and FMO transcript abundances in tissues from the two modern fern species Pteridium aquilinum and Phlebodium aureum.

a Two phenylalanine-derived cyanogenic glycosides have been reported from ferns: the monoglucoside prunasin (D-mandelonitrile-β-D-glucopyranoside) and the diglycoside vicianin (6-O-arabinopyranosylglucopyranoside). b Phylogenetic relationship between Pteridium aquilinum (Dennstaedtiaceae) and Phlebodium aureum (Polypodiaceae) showing that these two modern ferns species diversified 140 million years ago (tree adapted from43). c Content of vicianin across different tissue types of P. aureum (see also Supplementary Fig. 1), with the blue bars indicating the tissue selected for downstream transcriptomic analysis. d Content of prunasin in the pinnae of a population of 25 field-collected P. aquilinum, with the green bars indicating individuals selected for transcriptomic analysis. e Transcript abundance of predicted flavin monooxygenases (FMOs) in tissues of P. aquilinum and P. aureum containing high (gray bars) or low (black bars) cyanogenic glycoside levels. Arrows indicate candidate genes. TPM transcripts per million mapped reads. f Schematic illustration of identity and motifs in the transcriptome-deduced amino acid sequences of Paq18302 (PaqFOS1) and Pa22578. Differences between Pa22578 and the isolated PaFOS1 are indicated by blue lines. The position of putative binding motifs for FAD and NADPH, the FATGY and FMO-identifier motifs conserved across plant FMOs are highlighted. Supporting alignment is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

BLAST searches of the de novo assembled transcriptomes from Paq and Pa identified 139 CYPs in Paq compared to 120 in Pa (Supplementary Table 1). Neither genes encoding CYP79s nor CYPs with the CYP79 signature F/H substitution in the PERF region were identified29,30. Additional searches of the gene sequences deposited in the OneKP database31 confirmed the previously reported absence of CYP79 encoding gene sequences in ferns (Fig. 3)22,23. In the absence of CYP candidates, we extended the search to other gene families encoding monooxygenases with focus on genes showing interesting differential expression patterns of gene homologs within and between the two fern species.

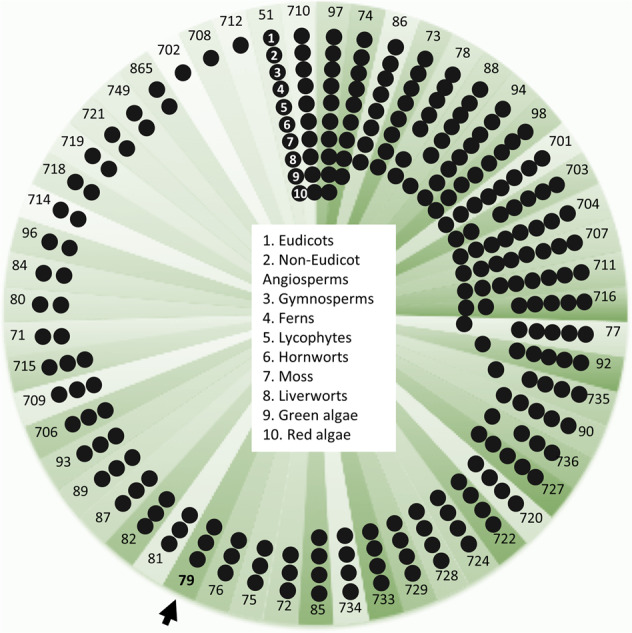

Fig. 3. Schematic diagram illustrating the occurrence of CYP families across plant taxa, based on the known CYP families present in eudicots.

The diagram is based on analysis of the OneKP database31, which includes transcriptomes from 74 ferns. The presence of 8930 cytochromes P450 fern sequences were predicted and sorted into families in accordance with nomenclature. The analyzed fern transcriptomes harbor at least 81 different P450 families of which 49 (60%) are novel fern-specific families. Approximately half of the CYP families present in higher plants are also found in ferns. The CYP79 family is present from gymnosperm to eudicots, but based on the >40% sequence identity, the CYP79 is absent in ferns. This also applies to the other known CYP families involved in cyanogenic glucoside biosynthesis in plants: the CYP71, CYP706, and CYP736 families.

The contig Pa22758 encoded a flavin-dependent monooxygenase ORF of 543 aa in accordance with a predicted full-length sequence32. Deep-mining of the transcriptome reads revealed that Pa contained variants of Pa22758 (Supplementary Fig. 2). The transcript level of this gene was 24-fold higher (−logFDR of 4.32) in Pa fiddlehead compared to the young pinnae (Fig. 2e). A reciprocal BLAST search between the predicted flavin-dependent monooxygenases of Paq and Pa identified a contig Paq18302 in Paq harboring a full-length nucleotide sequence encoding a flavin-dependent monooxygenase identical to the sequence of Pa22758, except for a single amino acid substitution. The expression level of Paq18302 showed a 23% increase (−logFDR of 0.50) in the individual containing higher levels of prunasin (Fig. 2e). The deduced amino acid sequences of the Pa and Paq flavin-dependent monooxygenases revealed that they contain conserved motifs specific to Class B flavin-dependent monooxygenases (Fig. 2f, Supplementary Fig. 2)33.

A BLAST search in the CATH: Protein Structure Classification Database (cathdb.info, version 4.2) with the Paq18302 protein sequence, classified the fern sequences as belonging to the Class B, flavin-dependent monooxygenases. These enzymes are characterized by being single-component FAD-binding enzymes harboring binding sites for the hydride electron donor NAD(P)H and molecular oxygen (CATH code 3.50.50.60)32,34,35.

Biochemical characterization of fern oxime synthase 1 (FOS1) in planta

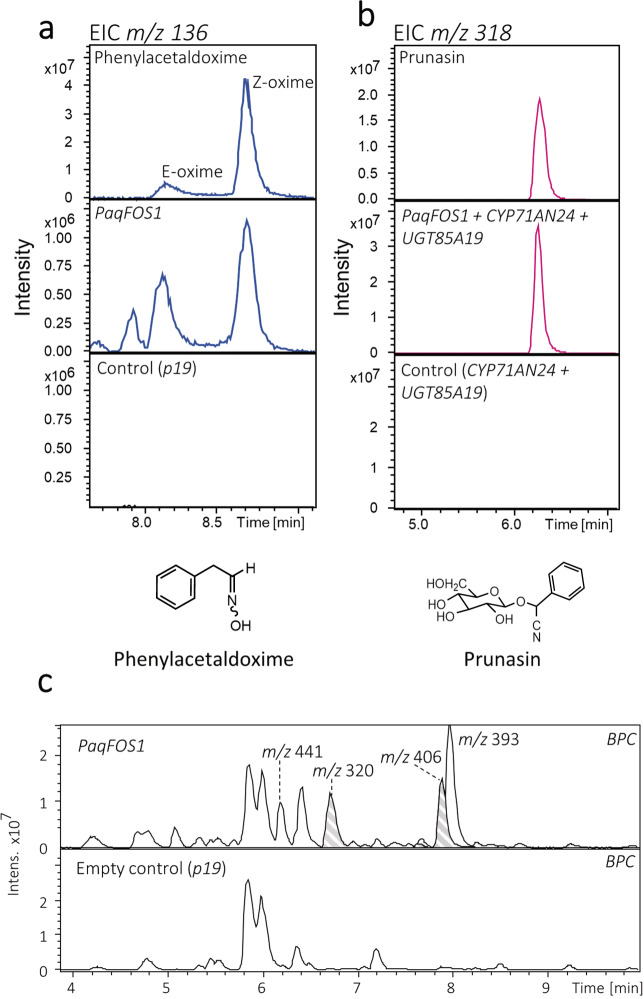

Functional characterization of the FMO enzyme Paq18302 (Fig. 4a) was obtained by Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transient expression of the encoding gene in Nicotiana benthamiana. Leaf discs of agro-infiltrated tissue were harvested after 4 days and subjected to metabolite profiling. Expression of the Paq18302 FMO afforded production of two constituents of m/z 136 eluting at rt = 8.17 and 8.70 min corresponding to the [M+H]+ adduct of (E)- and (Z)-phenylacetaldoxime, respectively, as verified by co-elution with an authentic standard (Fig. 4a). Two additional constituents were identified as a glucoside of phenylacetaldoxime (m/z 320, [M+Na]+ at rt = 6.7 min) and as a phenylacetaldoxime glucoside-malonic acid conjugate (m/z 406, [M+Na]+ at rt = 7.9 min) based on the diagnostic fragments in the MS/MS spectra (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Fig. 3)36–38. Identical oxime derivatives have previously been observed in N. benthamiana in response to expression of CYP79 enzymes10. Guided by Pa22758, the FMO encoding sequence from Pa was isolated from cDNA and shown by transient expression to be functionally equivalent to the Paq18302 FMO (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 4). We designate the orthologous FMO proteins as “FOS1”. Transient expression of FOS1 in N. benthamiana did not give rise to formation of other oximes or additional products, demonstrating that FOS1 has phenylalanine as its specific amino acid substrate.

Fig. 4. LC–MS based metabolite analyses of Nicotiana benthamiana leaves transiently expressing PaqFOS1.

a Extracted ion chromatograms (EICs) for m/z 136 corresponding to the [M+H]+ adduct of authentic phenylacetaldoxime (upper panel), metabolite extracts from N. benthamiana leaves expressing PaqFOS1 (middle panel) and empty vector control (lower panel). b m/z 318 EICs corresponding to the [M+Na]+ adduct of an authentic prunasin standard (upper panel), metabolite extracts from N. benthamiana transiently expressing PaqFOS1 in combination with PdCYP71AN24 and PdUGT85A194,14 (middle panel) and the control expressing PdCYP71AN24 and PdUGT85A19 (lower panel). c Base peak chromatograms (BPCs) of the metabolite extracts from N. benthamiana leaves expressing PaqFOS1 using expression of p19 as an empty vector control show the formation of additional products: m/z 320 at 6.7 min corresponds to the [M+Na]+ adduct of glucosylated phenylacetaldoxime; m/z 406 at 7.6 and 7.9 min correspond to the [M+Na]+ adduct of a glycosylated, phenylacetaldoxime-malonic acid conjugate; and m/z 393.11 at 8.1 min correspond to the [M+Na]+ adduct of phenylethanol glucoside malonate ester2,10. For MS/MS of additional products, see Supplementary Fig. 3.

Independent functional characterization of the FOS1 genes was obtained in N. benthamiana by co-expression with CYP71AN24 and UGT85A19, encoding the last two enzymes in the prunasin biosynthetic pathway in almond (Prunus dulcis)4,14. This resulted in production of prunasin as demonstrated by the formation of a constituent comigrating with an authentic standard with an extracted ion chromatogram (EIC) of m/z 318 corresponding to the [M+Na]+ adduct of prunasin (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 4). Neither phenylacetaldoxime nor prunasin are endogenous constituents of N. benthamiana.

In vitro assays revealed existence of N-hydroxyphenylalanine

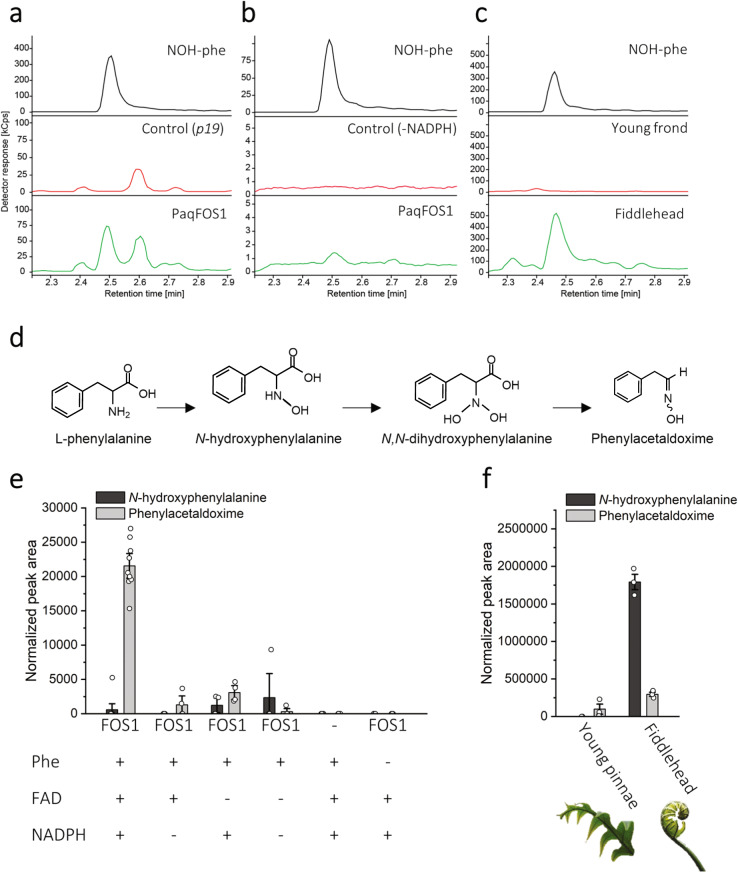

Of the limited number of FMOs characterized from plants, only YUCCA6 from A. thaliana and AsFMO from garlic (Allium sativum) have been successfully expressed and purified in enough quantity for downstream biochemical analyses33,39,40. Here, we expressed the PaqFOS1 protein with an N-terminal 6xHIS tag using Escherichia coli as a heterologous host and isolated PaqFOS1 by immobilized metal affinity chromatography followed by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) with a yield of 0.7 mg/L culture (Fig. 5). The isolated PaqFOS1 protein binds the cofactors FAD and NADPH as demonstrated by absorbance spectrometry, and migrates with an apparent molecular mass of 60 kDa on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 5) in agreement with a calculated molecular mass of 62.5 kDa. Upon SEC, PaqFOS1 eluted with a mass of 120 kDa suggesting that the native protein is a homodimer. In vitro assays of the isolated PaqFOS1 protein followed by LC–MS analyses confirmed that FOS1 can catalyze the conversion of phenylalanine to phenylacetaldoxime (Fig. 6). Concomitant production of N-hydroxyphenylalanine was also observed and verified using a chemically synthesized standard (Supplementary Fig. 8). Surprisingly, targeted LC–MS analysis of fiddleheads of Pa as well as of N. benthamiana leaves transiently expressing FOS1 demonstrated the in vivo presence of N-hydroxyphenylalanine in these tissues (Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. 5).

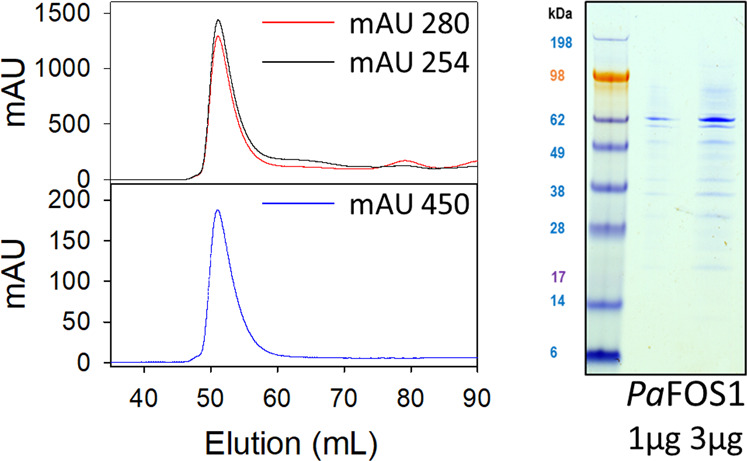

Fig. 5. Size exclusion chromatography elution profile of PaqFOS1 monitored at 280, 254, and 450 nm corresponding to absorbance (mAU) of the polypeptide, NADPH, and FAD, respectively.

Based on the elution volume in comparison to a set of reference proteins with known molecular masses, the PaqFOS1 protein eluted as a dimer with a mass of ~120 kDa. SDS-PAGE analysis of the PaqFOS1 containing fractions obtained by size exclusion chromatography demonstrating that PaqFOS1 migrated with an apparent molecular mass of 60 kDa in agreement with a calculated molecular mass of 62.5 kDa for the monomeric protein.

Fig. 6. The formation of N-hydroxyphenylalanine (NOH-phe).

LC–MS chromatograms from targeted analysis of samples compared with the authentic standard, derived from a transient expression of FOS1 in N. benthamiana showing the p19 as a negative control, b heterologous expression of FOS1 in E. coli using the absence of NADPH as a negative control, and c the presence of N-hydroxyphenylalanine in P. aureum tissue. The chromatographic trace represents the abundance of the fragment ion of N-hydroxyphenylalanine (precursor ion → fragment ion of 182.1 → 136.0; see Supplementary Table 4). d The hypothesized biosynthetic route from phenylalanine to phenylacetaldoxime, as catalyzed by FOS1. e In vitro activity assay of recombinant PaqFOS1 using l-phenylalanine (Phe) as a substrate, with different combinations of the necessary cofactors FAD and NADPH. Bars represent mean ± SE (n ≥ 3). f The presence of N-hydroxyphenylalanine in P. aureum fiddlehead and young pinnae metabolite extracts (n = 3).

Discussion

In this report, we identify and functionally characterize a flavin-dependent monooxygenase designated FOS1 from two modern fern species, Pa and Paq. Metabolite profiling of N. benthamiana leaves following transient expression of PaqFOS1 revealed the production of phenylacetaldoxime, which was also confirmed by the targeted in vitro experiments. When jointly expressed with CYP71AN24 and UGT85A19 from almond (Prunus dulcis), the entire prunasin pathway was established.

The FOS1 enzyme belongs to FMO class B, which are single-component FAD-binding enzymes that also harbor binding sites for the hydride electron donor NAD(P)H and molecular oxygen34,41. PaqFOS1 was isolated and purified as a functionally active homodimer. In vitro assays demonstrated that FOS1 is able to convert its substrate phenylalanine into two products, N-hydroxyphenylalanine and phenylacetaldoxime. The first product is obtained by a single N-hydroxylation reaction, the second by two consecutive N-hydroxylations followed by decarboxylation and dehydration reactions. In plants, the conversion of an amino acid to the corresponding aldoxime has only been reported as catalyzed by P450s from the CYP79 family. It is to be noted that an FMO from the actinomycete fungus Streptomyces coelicolor A3 can convert tryptophan and C5 prenylated tryptophan into their corresponding aldoximes42. Free N-hydroxyphenylalanine was also present in the fern tissue of Pa. N-hydroxylated protein amino acids have to our knowledge not previously been detected in biological tissues, and their functional roles remains unknown.

The 98% conservation of the FOS1 encoding gene sequences of Pa and Paq is remarkable. Among the total number of 55,000 and 63,000 gene sequences present in the transcriptomes of Pa and Paq, respectively, only 2% (1297 transcripts) share a sequence identity higher than 95%. Modern ferns diversified into the Pteridoids (including Paq) and Eupolypoids (including Pa) 140 million years ago (Fig. 2b)43. A blast search of the FOS1 gene sequence against the 68 fern transcriptomes available in the oneKP identified the presence of an identical transcript in Phlebodium pseudoaureum, a close relative to Pa. Deep mining of the transcriptomic resources documented the presence of homologous sequences across the evolutionary gap between these species (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). If a common ancestral FOS1 sequence was present in a progenitor to the derived ferns, the sequence has been under a remarkably high selection pressure. The four-electron oxidative decarboxylation reaction catalyzed by FOS1 is complex and may impose such a selection pressure. However, FMOs are “loaded guns” with the energy to drive an oxygenation reaction stored in the enzyme without precise docking of the substrate33,39. This can explain why N-hydroxyphenylalanine escapes the entire enzymatic reaction sequence and is present as an in vivo metabolite in Pa. N-hydroxyphenylalanine may have yet unrecognized functional roles in addition to being the initial intermediate in cyanogenic glycoside synthesis. The CYP79 family enzymes catalyzing the same set of reactions in higher plants show less sequence conservation. This may be because electron donation is provided to CYP enzymes by a separate NADPH-dependent cytochrome P450-oxidoreductase3,44. In CYP79-catalyzed reactions, all intermediates are bound within the active site as demonstrated by stable isotope experiments preventing release of the N-hydroxy amino acid intermediate45. Alternatively, the high sequence similarity between FOS1 from the two distantly related fern species may also reflect horizontal gene transfer. This phenomenon has been observed several times in fern species46,47. Ferns and other seed‐free plants may be more prone to horizontal gene transfer due to the weaker protection of the gametophytic eggs and sperm to the external environment, enabling transfer of genetic material48. Identification of the oxime-producing step in the cyanogenic fern species that phylogenetically lie within the 140 million years gap between Pa and Paq would establish the evolutionary relationships of these two ortholog genes.

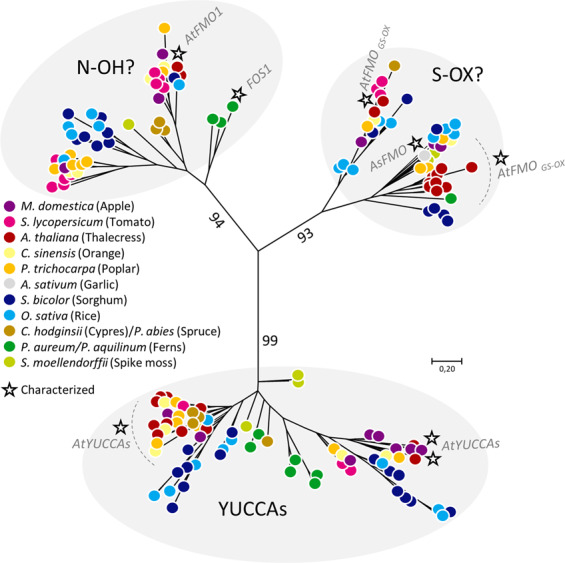

Class B flavin-dependent monooxygenases are found in all kingdoms of life35. All plant and animal flavin-dependent monooxygenases belong to this Class B FMO type, with a single exception of a Baeyer–Villiger monooxygense found in moss (Physcomitrella patens)33,49. The Arabidopsis thaliana genome contains 29 FMO genes32,33 and the human genome contains a gene cluster encoding five FMOs (FMO1-FMO5)50. The Pfam 31.0 database (accessed May 2020) lists a total of 1861 predicted Class B FMO sequences from 85 plant species (pfam.xfam.org51). To investigate the evolutionary diversity of plant FMOs, a representative set of FMO sequences from species representing land plant evolution, including the predicted full-length FMOs from fern transcriptomes (six from Pa and five from Paq, (Supplementary Fig. 6) and conifer (Chamaecyparis hodginsii and Picea abies) were used to build a phylogenetic tree (Fig. 7, Supplementary Table 4). The phylogenetic analysis includes representative functionally characterized FMOs: AsFMO1 from garlic (A. sativum) catalyzing S-oxygenation of allyl-mercaptan40, the A. thaliana YUCCAs involved in the biosynthesis of the phytohormone auxin52, the AtFMOGS-OX1-5 performing S-oxygenation of methylthioalkyl glucosinolates53, and A. thaliana AtFMO1 that catalyzes N-hydroxylation of pipecolic acid to form N-hydroxypipecolic acid, the critical signaling molecule in systemic acquired resistance54–56. The analysis shows that plant FMOs cluster in three phylogenetically distinct groups (Fig. 7), with each harboring members from all evolutionary distinct species from Selaginella (moss) to A. thaliana (angiosperm). This suggests an evolutionary split of the FMOs prior to emergence of the early land plants.

Fig. 7. Phylogenetic tree of the flavin monooxygenase (FMO) superfamily containing all predicted full-length FMOs from ferns (P. aureum and P. aquilinum) together with FMOs from eight higher plant species.

As all species are represented in each of the tree clades, the phylogenetic analysis suggests an early diversification of the groups prior to species differentiation. Employed sequence IDs are compiled in Supplementary Data 2. Characterized FMOs (or clusters of all characterized FMOs such as the Arabidopsis YUCCAs) are indicated by a star.

By adding fern FMOs to a plant FMO-specific phylogenetic tree, the role of the other putative fern monooxygenases can be hypothesized (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Fig. 6). The analysis identified six transcripts, three orthologues from each fern species, to cluster in the YUCCA clade. To date all characterized YUCCAs are involved in auxin biosynthesis, as they are proposed to catalyze a decarboxylation of indole-3-pyruvate acid to form IAA. An additional role of thiol reductase activity has been linked to these enzymes33,57. The establishment of a YUCCA-like mediated auxin function for fern FMOs would contribute to the evolutionary perspectives of hormone biosynthesis and signaling. PaFOS1 and PaqFOS1 group together with two additional FMO contigs (Pa22435 and Paq33416; Fig. 2e, Supplementary Fig. 6). This group of FMOs also encapsulates the AtFMO1 catalyzing N-hydroxylation of pipecolic acid54 (Fig. 7). Based on the phylogeny and functional characterization, we suggest that the group encapsulating PaFOS1, PaqFOS1, and AtFMO1 catalyze N-hydroxylation reactions. The PaqFOS1 and the AtFMO1 share 40% amino acid sequence identity (209/518) with a similarity score of 61% (318/518). As suggested by the SEC-elution profile, PaqFOS1 elutes solely as a homodimer. In parallel to PaqFOS1, we also expressed and isolated AtFMO1 and demonstrated that it also elutes as a homodimer (Supplementary Fig. 7). A dimeric FMO protein has previously been isolated and crystallized from the methylotropic bacterium Methylophaga58. Most recently, the crystal structures and proposed dimeric arrangement of class B FMOs from multicellular organisms were reported for the pyrrolizidine alkaloid N-oxygenase (ZvPNO) from the Locust grasshopper (Zonocerus variegatus)59 and for ancestral reconstructed mammalian FMOs60. Based on the sequence similarities and crystal structures obtained, and in agreement with the isolation of PaqFOS1 and AtFMO1 as stable homodimers, the tertiary structure of the class B FMOs are predicted to be conserved across the kingdoms of life.

Here, we show that an FMO catalyzing N-hydroxylation of an α-amino acid plays a key role in the convergent evolution of cyanogenic glycoside biosynthesis in ferns and higher plants. In all currently investigated gymnosperms and angiosperms, oxime formation from amino acids is catalyzed by a cytochrome P450 from the CYP79 family18. Our study demonstrates that the introduction of cyanogenic glycoside biosynthesis in ferns was based on independent recruitment of a unique class B FMO protein.

In addition to lacking a CYP79, ferns also lack the other cyanogenic glycoside-related CYP families: CYP71, CYP736, and CYP706 (Fig. 3). These families are all members of the large 71 clan, and selected members of these families catalyze conversion of oximes into the cyanohydrin intermediate in seed plants (Fig. 1). This opens speculation on the possible identity of the remaining biosynthetic pathway members in ferns. Based on less than 40% amino acid sequence identity criteria, many of the CYPs identified in the Pa and Paq transcriptomes did not correspond to any previously named and characterized P450 families. This study therefore unmasks a treasure trove of what is to our knowledge new CYP families and possible pathway candidates. Interestingly, other families of the 71 clan are also highly abundant in fern species61, and would be possible targets for gene discovery. The diversity of previously unnamed CYP families accentuates convergent evolution of cyanogenic glycoside biosynthesis as well as other metabolic pathways in ferns. Our comparative transcriptomic strategy to identify FOS1 was highly successful, and would provide a robust approach to identify the remaining pathway members.

The evolution of the cyanogenic glycoside pathway is quite dynamic12. Recently, the classical three-step pathway was revised, with the discovery that sugar gum (Eucalyptus cladocalyx) harbors four genes that catalyze the conversion of amino acid to cyanogenic glycoside10. It is therefore also a possibility that more (or less) biosynthetic steps and intermediates might be present in ferns. Further, the cyanogenic glycoside biosynthetic pathway is shown to act as a dynamic metabolon, ensuring channeling of intermediates62. Here, Sorghum bicolor metabolons encounter the soluble UGT into tight organization. A likewise orchestration of FOS1 into a membrane-bound complex could be plausible, and indeed FMO from humans are associated with the membrane50,60,63. The identification of FOS1 in cyanogenic ferns alters traditional perceptions of the origin of cyanogenic glycoside biosynthesis, and highlights the importance of N-hydroxy amino acids, oximes, and cyanogenic glycosides throughout plant evolution.

At present, only a few plant FMOs have been functionally characterized. These FMOs have been shown to catalyze unique and crucial oxygenation reactions in plant hormone metabolism, pathogen resistance, signaling and chemical defense32. Our study demonstrates that the N-hydroxylating capacity of plant FMOs participate in the direct synthesis of a plant defense compound, and possible formation of undiscovered new metabolites via an N-hydroxy amino acid intermediate. Furthermore, this example of convergent evolution by the recruitment of different enzyme families—specifically showing that a soluble FMO can catalyze the same reaction as a membrane-bound cytochrome P450—opens opportunities for industrial applications in the future.

Methods

Plant material

Plant material for metabolite and RNA extraction was obtained from Pa (previously Polypodium aureum) grown in glass house at the Botanical Garden of Copenhagen (Plant ID E615) and from Pteridium aquilinum (Paq) collected at Dronningens Bøge, Esrum Lake, Nødebo, on June 17, 2015 (55°59′49.9″N, 12°21′27.6″E). Tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until further analyses.

Metabolite profiling of fern tissue

Plant tissue (~30 mg) was weighed and boiled in 85% methanol (v/v, 300 μL) for 5 min. The vial was transferred to an ice bath and the material macerated with a small pestle. The supernatant obtained after centrifugation (13,000 × g, 1 min) was filtered (0.45 μm low-binding Durapore membrane) and diluted 1:5 in water prior to LC–MS analysis.

Analytical LC–MS was carried out using an Agilent 1100 Series LC (Agilent Technologies, Germany) coupled to an HCT Ultra ion trap mass spectrometer running in positive electrospray ionization (ESI) ultra-scan mode (Bruker, Bremen, Germany). The LC was fitted with a Zorbax SB-C18 column (2.1 × 50 mm, 1.8 μm; Agilent Technologies) and operated at 35 °C, with a flow rate of 0.2 mL min−1. The mobile phases were: (a) 0.1% HCOOH (v/v) and 50 μM NaCl; and (b) 0.1% HCOOH in MeCN (v/v). The gradient program was: 0–0.5 min, isocratic phase 2% B; 0.5–7.5 min, linear gradient 2–40% B; 7.5–8.5 min, linear gradient 40–90% B; 8.5–11.5 min, isocratic phase 90% B; 11.5–18 min, isocratic phase 2% B. The flow rate was raised to 0.3 mLmin −1 in the interval 11.2–13.5 min. Traces of total ion current and of extracted ion currents for specific [M+Na]+ and [M+H]+ adduct ions were used to identify the eluted constituents using Compass DataAnalysis software (version 4.2, Bruker Daltonics). See below for targeted analytical LC–MS analysis of N-hydroxyphenylalanine from Pa tissue.

RNA isolation and transcriptome mining

Total RNA was prepared from 30 to 50 mg of plant tissue using the Spectrum Plant Total RNA Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, US). Transcriptomes were prepared from mRNA isolated from Pa fiddlehead, Pa young frond, and from two Paq frond tips containing high and low cyanogenic glycoside levels. Transcriptome sequencing was carried out by Macrogen (Seoul, South Korea) using an Illumina HiSeq2000 sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, CA) to generate paired-end libraries. The reads were de novo assembled and relative transcript abundance estimated by Sequentia Biotech (www.sequentiabiotech.com) using the Trinity pipeline64.

The expression level of all transcripts was quantified. Identification of gene families was performed using the OrthoMCL pipeline (http://orthomcl.org/orthomcl/about.do). Differential gene expression analyses based on the Pa and Paq transcriptomes were carried out using eXpress65 and the data transferred into R and analyzed with the package NOISeq66.

Isolation and transient expression of FMO candidate genes

The full-length sequence of the predicted ORF Paq18302 encoding gene (most upstream methionine) without codon optimization was fitted with attb1 and attb2 Gateway cloning sites: attB1: ggggacaagtttgtacaaaaaagcaggct, attB2: ggggaccactttgtacaagaaagctgggt and synthesized by GenScript. Guided by Pa22758, we isolated the full length of the FMO sequence from Pa cDNA using gene specific primers flanked by gateway sites (Forward: ggggaccactttgtacaagaaagctgggtctattcatctttgtagtccatgtta, Reverse: ggggaccactttgtacaagaaagctgggtctattcatctttgtagtccatgtta) and by PCR attached the gateway sites. The fragment was cloned into pUC57. Both constructs were subcloned by Gateway recombination from the pUC57 vector into the expression vector pEAQ3-HT-DEST67.

Cells from overnight cultures of Agrobacterium tumefaciens (AGL1) containing expression constructs with the target gene sequence under the control of CamV-35S promoter/terminator elements in pEAQ (PaqFOS1) or pJAM1502 (CYP71AN24, UGT85A19) or the gene sequence for the gene-silencing inhibitor protein p1968,69 were harvested by centrifugation (4000 × g, 10 min) and resuspended to OD600 0.8 in water. After 1 h incubation at ambient temperature, the A. tumefaciens cultures were used to co-infiltrate leaves of 3–4 weeks old Nicotiana benthamiana plants. After 4–5 days, leaf discs (1 cm diameter) were excised from infiltrated leaves, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and subsequently ground and extracted in 200 μL 85% MeOH (v/v) for metabolite profiling as described above. Analytical LC–MS of extracts of infiltrated leaves was carried out either as described above using the ion trap instrument or using a Dionex Ultimate 3000 RS UHPLC (Thermo Fisher Scientific) system with DAD detector and fitted with a Phenomenex Kinetex® XB-C18 column (1.7 μm, 100 × 21 mm; Phenomenex, US) operated at 40 °C and with a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min. The mobile phases were: (a) 0.1% HCOOH (v/v) and 50 mM NaCl; and (b) 0.1% HCOOH in MeCN (v/v). The gradient program: 0–1 min, isocratic gradient 5% B; 1–7 min, linear gradient 5%–70%; 7–8 min, linear gradient 70–100%; 8–10 min isocratic 100% B; 10–11 min, linear gradient 100–5% B; 11–16 min, isocratic 5% B. The UHPLC system was coupled to a compact™ qToF (Bruker Daltonics) mass spectrometer run in negative ESI mode from 50 to 1200 m/z. Raw data were processed using Compass DataAnalysis software (version 4.2, Bruker Daltonics).

Generation of expression plasmids for paqFOS1 and AtFMO1

The nucleotide sequence of contig Paq18305 and of AtFMO1 from A. thaliana (Q9LMA1) was codon optimized for expression in E. coli fitted with an upstream 6xHis encoding tag and inserted into the expression vector pET-30a(+). To express the recombinant proteins, both pET-30a-PaqFOS1 and pET-30a-AtFMO1 were transformed into Phage-resistant BL21(DE3)-R3 strain (Structural Genomics Consortium Oxford).

Expression and isolation of recombinant PaqFOS1 in E. coli

A single colony from a fresh plate (1.5% LB-agar containing 50 µg/mL kanamycin and 25 µg/mL chloramphenicol) was grown O/N at 37 °C with shaking (250 rpm) in 250 mL LB medium supplemented with kanamycin and chloramphenicol. A 4 L expression batch was set up by inoculation each liter of LB medium (supplemented with kanamycin and chloramphenicol) with 20 mL of bacterial culture into four 2.5 L Ultra Yield flasks fitted with AirOtop enhanced seals (Thomson Instrument, Germany). Preinduction cultures were incubated at 37 °C and 225 rpm to reach OD 1.2–1.5 before induction with IPTG (final concentration 0.5 mM). The expression culture was grown O/N at 18 °C and the E. coli cells sedimented (5000 × g, 10 min) and stored at −20 °C until used.

E. coli cells were thawed and resuspended in lysis buffer (1 g cells per 5 mL buffer; 100 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 0.5 mM TCEP, Benzonase (25 U/mL; Sigma-Aldrich)) and lysed in a high-pressure homogenizer (Avestin EmulsiFlex D20, 40 psi). The lysate was clarified by centrifugation (11,000 rpm, 40 min), filtered (0.22 μM) and applied to two 5-mL His-Trap FF columns (GE Healthcare) connected in line and preequilibrated with Binding buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM Imidazole, 0.5 mM TCEP). Columns were washed with ten column volumes of wash buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 30 mM Imidazole, 0.5 mM TCEP) and protein eluted using a ten column volume 0–100% gradient of elution Buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 500 mM Imidazole, 0.5 mM TCEP). The eluate was collected in 1.5 mL fractions in 96-wells plates. Fractions of interest were analyzed by SDS-PAGE using 4–12% NuPAGE gradient protein gels (Thermo Scientific). Fractions containing the target protein were concentrated to a final total volume of 5 mL by centrifugation using preequilibrated membrane filters (30 kDa cut off; Thermo scientific) and applied to a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 column (120 mL, GE Healthcare). Before usage, columns were calibrated using the High molecular weight calibration kit (ranging from 43 to 669 kDa; GE Healthcare) and preequilibrated using gel filtration (GF) buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM TCEP), which was also used for eluting the protein. All buffers, except the GF buffer, contained one tablet cOmplete protease inhibitor cocktail pr. Fifty milliliters of buffer (cOmplete Inhibitor, EDTA-free, Roche). The isolated protein was frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

Recombinant enzyme assays

The activity of the isolated recombinant FOS1 protein was determined in vitro in assay mixtures (total volume: 50 µL) containing 30 µL of diluted FOS1 protein (0.345 mg mL−1) reconstituted with FAD (10 µM final concentration) and phenylalanine (50 µM final concentration). Enzyme reaction was initiated by addition of NADPH (final concentration 6 mM). Following incubation (1 h, 30 °C, 300 rpm), the reaction was stopped by addition of 100 µL MeOH. Assays without enzyme, substrate, or cofactor served as controls. All assays were carried out in triplicates.

Analysis of recombinant PaqFOS1 and Pa tissue

Enzyme reaction mixtures (50 µL aliquots) were diluted with 50 µL Milli-Q grade water and filtered (Durapore® 0.22 μm PVDF filter plates, Merck Millipore, Tullagreen, Ireland) together with filtered and diluted MeOH extracts of Pa fiddlehead and young pinna (see above). Samples were chromatographically separated using an Advance UHPLC system (Bruker, Bremen, Germany) fitted with a Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18 column (100 × 3.0 mm, 1.8 µm, Agilent Technologies, Germany) with a column temperature maintained at 40 °C. The mobile phases were: (a) HCOOH (0.05%, v/v); and (b) MeCN in 0.05% (v/v) HCOOH. The gradient elution profile was: 0–0.5 min, isocratic phase 3% B; 0.5–3.8 min, linear gradient 3–70% B; 3.8–4.4 min. linear gradient 70–100% B; 4.4–4.9 min, isocratic phase 100% B, 4.9–5.0 min, linear gradient 100–3% B; 5.0–6.0 min, isocratic phase 3% B using a flow rate of 0.5 mL min−1. The EVOQ Elite Triplequadrupole mass spectrometer (Bruker, Bremen, Germany) was equipped with an ESI operated in positive mode. The instrument parameters were optimized by infusion experiments with pure standards. The ion spray voltage was maintained at +4000 V, cone temperature was set to 350 °C and cone gas to 20 psi. Heated probe temperature was set to 400 °C and probe gas flow to 50 psi. Nebulizing gas was set to 60 psi and collision gas to 1.6 mTorr. Nitrogen was used as probe and nebulizing gas, and argon as collision gas. Active exhaust was constantly on. Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) was used to monitor analyte parent ion → product ion transitions. MRM transitions and collision energies were optimized by direct infusion experiments into the MS (Supplementary Table 4). Both Q1 and Q3 quadrupoles were maintained at unit resolution. Bruker MS Workstation software (Version 8.2.1, Bruker, Bremen, Germany) was used for data acquisition and processing.

Phylogenetic analysis

FMO sequences from angiosperms and mosses were accessed from Phytozome (phytozome.jgi.doe.gov, version 12.1.6). The following eight species were selected to span the evolution of higher plants: Malus domestica, Solanum lycopersicum, Arabidopsis thaliana, Citrus sinensis, Populus trichocarpa, Sorghum bicolor, Oryza sativa, and Selaginella moellendorffii. Their FMO sequences were obtained using BLASTp 2.2.26+ with the A. thaliana FMOs as query sequences resulting in a total of 169 hits. Fern sequences were accessed from the transcriptomes of Pa and Paq reported in the present study (Paq- or PaTRINITY). To obtain robust phylogenetics, only full-length sequences were included. In all cases the ORF and initial methionine were chosen. FMO sequences from conifers were obtained from the databases OneKP (ualberta.ca/onekp) and Congenie (congenie.org) by blast-searching Chamaecyparis hodginsii (four sequences) and Picea abies (four sequences) with Arabidopsis FMOs as query sequences. The functionally characterized S-oxygenating FMO (AsFMO1) from garlic (Allium sativum) was also included40,70. Sequence analyses were conducted using MEGA 7.0. All amino acid sequences were manually inspected before being aligned using ClustalW. The phylogenetic relationship was inferred using the maximum likelihood method based on the JTT matrix-based model and n = 100 replicates for bootstrapping. The phylogenetic tree is drawn to scale, not rooted, and with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. The analysis involved 189 amino acid sequences. The sequence IDs employed in the phylogenetic analysis can be found in Supplementary Data 2.

Small read archive (SRA) searches for FOS1 orthologues

Data from the fern whole genome duplication study at Fudan University were retrieved from NCBI (accession PRJNA422112, date 12 December 2017). The SRA searches were carried out using PaqFOS1 as query. An FMO hit was obtained from all but four of the 119 fern transcriptomes, using a conserved N-terminal fragment as query.

Chemicals

[UL-14C]-l-phenylalanine (0.25 μCi, specific activity 487 mCi mmol−1) was purchased from Perkin-Elmer. N-hydroxyphenylalanine, (E)- and (Z)-phenylacetaldoxime and prunasin were chemically synthesized as previously reported71–73. Specifically, chemical synthesis of L-(N-hydroxy)phenylalanine is outlined in Supplementary Fig. 8. Vicianin was obtained from a methanol extract of Vicia sativa seeds. Compound validation was based on UV absorption and accurate mass upon LC–MS analysis. Quantification of vicianin was carried out using a dilution series of amygdalin as reference compound, as the diglycosides are structurally comparable and expected to behave similarly with respect to their degree of ionization and UV absorption.

Statistics and reproducibility

The fern species were chosen based on published literature reports of cyanogenic glycoside content, and confirmed by LC–MS analysis. RNA was extracted from identified tissue at least twice, with the highest quality RNA used for downstream transcriptomic analysis. Functional characterization by agroinfiltration in Nicotiana benthamiana plants was repeated in three independent experiments, using two biological N. benthamiana replicates, and three technical replicates each time. Similarly, in vitro enzyme assays in E. coli were repeated in three independent experiments with three technical replicates each time. FOS1 constructs expressed in A. tumefaciens and E. coli were confirmed by sequencing.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Items

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Protein Production and Characterization Platform at the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Protein Research for offering instruments and protocols for expression and purification. Gardeners Sue Dix and Jimmy Oluf Olsen, The Botanical Garden, University of Copenhagen, are thanked for taking good care of Pa. We acknowledge Søren Bak, Fernando Geu-Flores, and the Theme Group students over the years for their shared enthusiasm in ferns metabolic evolution. Laboratory technicians Susanne Bidstrup, Lene Dalsten, and Theme Group students in 2018 are thanked for assistance in RNA extraction, cloning, and sequencing. Riccardo Aiese Cigliano from Sequentia Biotech is thanked for assistance with transcriptomic assembly and bioinformatics analyses. This work was supported by the VILLUM Center for Plant Plasticity (VKR023054) (B.L.M.); the European Research Council Advanced Grant (ERC-2012-ADG_20120314) (B.L.M.); VILLUM Young Investigator Grant (VKR013167) (E.H.J.N.); a Danish Independent Research Council Sapere Aude Research Talent Post-Doctoral Stipend (6111-00379B) (E.H.J.N.); and a Novo Nordisk Emerging Investigator Grant (Grant No. 0054890) (E.H.J.N.). The financial support is gratefully acknowledged.

Author contributions

S.T., B.L.M., D.R.N., and E.H.J.N. initiated the study; S.T. and A.K.B. collected plant material and performed metabolite analysis; S.T. prepared RNA, performed transcriptomic analysis, and identified candidate genes. S.T., M.S., and A.K.B. carried out transient expression experiments; S.T., M.S., and M.B. carried out protein isolation; S.T. and M.S. carried out enzyme assays; S.T., M.S., and C.C. carried out LC–MS analyses; M.S.M. conducted chemical synthesis; S.T. carried out phylogenetic analyses; D.R.N. performed data mining from transcriptomes and the short read archive; S.T., M.S., E.H.J.N., and B.L.M. wrote the manuscript with input from all other authors.

Data availability

The OneKP database is accessible at (ualberta.ca/onekp). The data from 120 SRA experiments are residing at NCBI as the fern whole genome duplication study with accession PRJNA422112. All other data are available in the main text or in the supplementary materials (Supplementary Data 1–3). Sequence data from this article can be found in the EMBL/GenBank data libraries under accession numbers MT856954 and MT856955 for the fern oxime synthase Paq18302 and Pa22578.

Code availability

Details about software and algorithms used in this study are given in the “Methods” section. No customized code or algorithm deemed central to the conclusion was used.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Sara Thodberg, Mette Sørensen.

Change history

1/10/2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: The Acknowledgements have been corrected.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s42003-020-01224-5.

References

- 1.Harper, N. L., Cooper-Driver, G. A. & Swain, T. A survey for cyanogenesis in ferns and gymnosperms. Phytochemistry15, 1764–1767 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gleadow, R. M. & Møller, B. L. Cyanogenic glycosides: synthesis, physiology, and phenotypic plasticity. Ann. Rev. Plant Biol.65, 155–185 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luck, K. et al. CYP79 P450 monooxygenases in gymnosperms: CYP79A118 is associated with the formation of taxiphyllin in Taxus baccata. Plant Mol. Biol.95, 169–180 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thodberg, S. et al. Elucidation of the amygdalin pathway reveals the metabolic basis of bitter and sweet almonds (Prunus dulcis). Plant Phys.178, 1096–1111 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanchez-Perez, R. et al. Mutation of a bHLH transcription factor allowed almond domestication. Science364, 1095–1098 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Møller, B. L. Functional diversifications of cyanogenic glucosides. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol.13, 338–347 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Picmanova, M. et al. A recycling pathway for cyanogenic glycosides evidenced by the comparative metabolic profiling in three cyanogenic plant species. Biochem J.469, 375–389 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bjarnholt, N. et al. Glutathione transferases catalyze recycling of auto‐toxic cyanogenic glucosides in sorghum. Plant J.94, 1109–1125 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ionescu, I. A. et al. Transcriptome and metabolite changes during hydrogen cyanamide-induced floral bud break in sweet cherry. Front. Plant Sci.8, 10.3389/fpls.2017.01233 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Hansen, C. I. C. et al. Reconfigured cyanogenic glucoside biosynthesis in Eucalyptus cladocalyx involves a cytochrome P450 CYP706C55. Plant Phys.178, 1081–1095 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamaguchi, T., Yamamoto, K. & Asano, Y. Identification and characterization of CYP79D16 and CYP71AN24 catalyzing the first and second steps in L-phenylalanine-derived cyanogenic glycoside biosynthesis in the Japanese apricot, Prunus mume Sieb. et Zucc. Plant Mol. Biol.86, 215–223 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takos, A. M. et al. Genomic clustering of cyanogenic glucoside biosynthetic genes aids their identification in Lotus japonicus and suggests the repeated evolution of this chemical defence pathway. Plant J.68, 273–286 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clausen, M. et al. The bifurcation of the cyanogenic glucoside and glucosinolate biosynthetic pathways. Plant J.84, 558–573 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franks, T. K. et al. A seed coat cyanohydrin glucosyltransferase is associated with bitterness in almond (Prunus dulcis) kernels. Funct. Plant Biol.35, 236–246 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sibbesen, O., Koch, B., Halkier, B. A. & Møller, B. L. Cytochrome P-450TYR is a multifunctional heme-thiolate enzyme catalyzing the conversion of L-tyrosine to p-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde oxime in the biosynthesis of the cyanogenic glucoside dhurrin in Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench. J. Biol. Chem.270, 3506–3511 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vazquez-Albacete, D. et al. The CYP79A1 catalyzed conversion of tyrosine to (E)-p-hydroxyphenylacetaldoxime unravelled using an improved method for homology modeling. Phytochemistry135, 8–17 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen, K., Osmani, S. A., Hamann, T., Naur, P. & Møller, B. L. Homology modeling of the three membrane proteins of the dhurrin metabolon: catalytic sites, membrane surface association and protein-protein interactions. Phytochemistry72, 2113–2123 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sørensen, M., Neilson, E. H. J. & Møller, B. L. Oximes: unrecognized chameleons in general and specialized plant metabolism. Mol. Plant11, 95–117 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glawischnig, E., Hansen, B. G., Olsen, C. E. & Halkier, B. A. Camalexin is synthesized from indole-3-acetaldoxime, a key branching point between primary and secondary metabolism in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA101, 8245–8250 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sugawara, S. et al. Biochemical analyses of indole-3-acetaldoxime-dependent auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA106, 5430–5435 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nonhebel, H. et al. Redirection of tryptophan metabolism in tobacco by ectopic expression of an Arabidopsis indolic glucosinolate biosynthetic gene. Phytochemistry72, 37–48 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li, F. W. et al. Fern genomes elucidate land plant evolution and cyanobacterial symbioses. Nat. Plants4, 460–472 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelson, D. & Werck-Reichhart, D. A P450-centric view of plant evolution. Plant J.66, 194–211 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santos, M. et al. Phytochemical Studies in Pteridophytes Growing in Brazil: A Review, Americas J. Plant Sci. Biotech,Vol 4, (Global Science Books, 2010).

- 25.Smith, A. R. et al. Fern classification. in Biology and Evolution of Ferns and Lycophytes (Tom A. Ranker and Christopher H. Haufler, editors), 417–467 (Cambridge University Pressm, 2008). 10.1017/Cbo9780511541827.017.

- 26.Adsersen, A., Adsersen, H. & Brimer, L. Cyanogenic constituents in plants from the Galápagos Islands. Biochem. Syst. Ecol.16, 65–77 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lizotte, P. A. & Poulton, J. E. Identification of (R)-vicianin in Davallia trichomanoides blume. Z. Naturforsc. J. Biosci.41, 5–8 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wajant, H., Forster, S., Selmar, D., Effenberger, F. & Pfizenmaier, K. Purification and characterization of a novel (R)-mandelonitrile lyase from the fern Phlebodium aureum. Plant Phys.109, 1231–1238 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bak, S et al. Cytochromes P450. in The Arabidopsis Book. e0144 (American Society of Plant Biologists, 2011). 10.1199/tab.0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Werck-Reichhart, D. & Feyereisen, R. Cytochromes P450: a success story. Genome Biol.1, 3003.3001–3003.3009 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leebens-Mack, J. H. et al. One thousand plant transcriptomes and the phylogenomics of green plants. Nature574, 679–685 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schlaich, N. L. Flavin-containing monooxygenases in plants: looking beyond detox. Trends Plant Sci.12, 412–418 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thodberg, S. & Jakobsen Neilson, E. H. The “green” FMOs: diversity, functionality and application of plant flavoproteins. Catalysts10, 329 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mascotti, M. L., Ayub, M. J., Furnham, N., Thornton, J. M. & Laskowski, R. A. Chopping and changing: the evolution of the flavin-dependent monooxygenases. J. Mol. Biol.428, 3131–3146 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huijbers, M. M. E., Montersino, S., Westphal, A. H., Tischler, D. & van Berkel, W. J. H. Flavin dependent monooxygenases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys.544, 2–17 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tian, L. & Dixon, R. A. Engineering isoflavone metabolism with an artificial bifunctional enzyme. Planta224, 496–507 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Franzmayr, B. K., Rasmussen, S., Fraser, K. M. & Jameson, P. E. Expression and functional characterization of a white clover isoflavone synthase in tobacco. Ann. Bot.110, 1291–1301 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ting, H. M. et al. The metabolite chemotype of Nicotiana benthamiana transiently expressing artemisinin biosynthetic pathway genes is a function of CYP71AV1 type and relative gene dosage. N. Phytol.199, 352–366 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dai, X. et al. The biochemical mechanism of auxin biosynthesis by an arabidopsis YUCCA flavin-containing monooxygenase. J. Biol. Chem.288, 1448–1457 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valentino, H. et al. Structure and function of a flavin-dependent S-monooxygenase from garlic (Allium sativum). J. Biol. Chem.10.1074/jbc.RA120.014484 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Furnham, N. et al. Exploring the evolution of novel enzyme functions within structurally defined protein superfamilies. Plos Comput. Biol.8, e1002403. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002403 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Ozaki, T., Nishiyama, M. & Kuzuyama, T. Novel tryptophan metabolism by a potential gene cluster that is widely distributed among actinomycetes. J. Biol. Chem.288, 9946–9956 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schneider, H. et al. Ferns diversified in the shadow of angiosperms. Nature428, 553–557 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laursen, T. et al. Single molecule activity measurements of cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase reveal the existence of two discrete functional states. ACS Chem. Biol.9, 630–634 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Halkier, B. A., Lykkesfeldt, J. & Møller, B. L. 2-nitro-3-(p-hydroxyphenyl)propionate and aci-1-nitro-2-(p-hydroxyphenyl)ethane, two intermediates in the biosynthesis of the cyanogenic glucoside dhurrin in Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA88, 487–491 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davis, C. C., Anderson, W. R. & Wurdack, K. J. Gene transfer from a parasitic flowering plant to a fern. Proc. Biol. Sci.272, 2237–2242 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li, F.-W. et al. Horizontal transfer of an adaptive chimeric photoreceptor from bryophytes to ferns. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA111, 6672–6677 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wickell, D. A. & Li, F.-W. On the evolutionary significance of horizontal gene transfers in plants. N. Phytol.225, 113–117 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beneventi, E., Niero, M., Motterle, R., Fraaije, M. & Bergantino, E. Discovery of Baeyer–Villiger monooxygenases from photosynthetic eukaryotes. J. Mol. Catal. B98, 145–154 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krueger, S. K. & Williams, D. E. Mammalian flavin-containing monooxygenases: structure/function, genetic polymorphisms and role in drug metabolism. Pharmacol. Ther.106, 357–387 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Finn, R. D. et al. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucl. Acids Res.42, D222–D230 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao, Y. et al. A role for flavin monooxygenase-like enzymes in auxin biosynthesis. Science291, 306–309 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hansen, B. G., Kliebenstein, D. J. & Halkier, B. A. Identification of a flavin-monooxygenase as the S-oxygenating enzyme in aliphatic glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J.50, 902–910 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mishina, T. E. & Zeier, J. The arabidopsis flavin-dependent monooxygenase FMO1 is an essential component of biologically induced systemic acquired resistance. Plant Phys.141, 1666 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen, Y. C. et al. N-hydroxy-pipecolic acid is a mobile metabolite that induces systemic disease resistance in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA115, E4920–E4929 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hartmann, M. et al. Flavin monooxygenase-generated N-hydroxypipecolic acid is a critical element of plant systemic immunity. Cell173, 456–469.e416 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cha, J.-Y. et al. A novel thiol-reductase activity of Arabidopsis YUC6 confers drought tolerance independently of auxin biosynthesis. Nat. Commun.6, 8041 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alfieri, A., Malito, E., Orru, R., Fraaije, M. W. & Mattevi, A. Revealing the moonlighting role of NADP in the structure of a flavin-containing monooxygenase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA105, 6572–6577 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kubitza, C. et al. Crystal structure of pyrrolizidine alkaloid N-oxygenase from the grasshopper Zonocerus variegatus. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol.74, 422–432 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nicoll, C. R. et al. Ancestral-sequence reconstruction unveils the structural basis of function in mammalian FMOs. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol.10.1038/s41594-019-0347-2 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Sanchez-Perez, R., Jorgensen, K., Olsen, C. E., Dicenta, F. & Møller, B. L. Bitterness in almonds. Plant Physiol.146, 1040–1052 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Laursen, T. et al. Characterization of a dynamic metabolon producing the defense compound dhurrin in sorghum. Science354, 890–893 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Williams, D. E., Hale, S. E., Muerhoff, A. S. & Masters, B. S. Rabbit lung flavin-containing monooxygenase. Purification, characterization, and induction during pregnancy. Mol. Pharm.28, 381–390 (1985). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Haas, B. J. et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat. Protoc.8, 1494–1512 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roberts, A. & Pachter, L. Streaming fragment assignment for real-time analysis of sequencing experiments. Nat. Methods10, 71 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tarazona, S. et al. Data quality aware analysis of differential expression in RNA-seq with NOISeq R/Bioc package. Nucleic Acids Res.43, e140 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sainsbury, F., Thuenemann, E. C. & Lomonossoff, G. P. pEAQ: versatile expression vectors for easy and quick transient expression of heterologous proteins in plants. Plant Biotechnol. J.7, 682–693 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Voinnet et al. Suppression of gene silencing: A general strategy used by diverse DNA and RNA viruses of plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Nov 1999, 96, 14147–14152. 10.1073/pnas.96.24.14147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Voinnet et al. Suppression of gene silencing: A general strategy used by diverse DNA and RNA viruses of plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Aug 2015, 112, E4812. 10.1073/pnas.1513950112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.Yoshimoto, N. et al. Identification of a flavin-containing S-oxygenating monooxygenase involved in alliin biosynthesis in garlic. Plant J.83, 941–951 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ferreira-Silva, B., Lavandera, I., Kern, A., Faber, K. & Kroutil, W. Chemo-promiscuity of alcohol dehydrogenases: reduction of phenylacetaldoxime to the alcohol. Tetrahedron66, 3410–3414 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Møller, B. L., Olsen, C. E. & Motawia, M. S. General and stereocontrolled approach to the chemical synthesis of naturally occurring cyanogenic glucosides. J. Nat. Prod.79, 1198–1202 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Oppolzer, W., Tamura, O. & Deerberg, J. Asymmetric-synthesis of α-amino acids and α-N-hydroxyamino acids from N-acylbornane-10,2-sultams-1-chloro-1-nitrosocyclohexane as a practical [NH2+] equivalent. Helv. Chim. Acta75, 1965–1978 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Koch, B. M., Sibbesen, O., Halkier, B. A., Svendsen, I. & Møller, B. L. The primary sequence of cytochrome P450tyr, the multifunctional N-hydroxylase catalyzing the conversion of L-tyrosine to p-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde oxime in the biosynthesis of the cyanogenic glucoside dhurrin in Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench. Arch. Biochem. Biophys.323, 177–186 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bak, S., Kahn, R. A., Nielsen, H. L., Moller, B. L. & Halkier, B. A. Cloning of three A-type cytochromes p450, CYP71E1, CYP98, and CYP99 from Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench by a PCR approach and identification by expression in Escherichia coli of CYP71E1 as a multifunctional cytochrome p450 in the biosynthesis of the cyanogenic glucoside dhurrin. Plant Mol. Biol.36, 393–405 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jones, P. R., Møller, B. L. & Hoj, P. B. The UDP-glucose:p-hydroxymandelonitrile-O-glucosyltransferase that catalyzes the last step in synthesis of the cyanogenic glucoside dhurrin in Sorghum bicolor. Isolation, cloning, heterologous expression, and substrate specificity. J. Biol. Chem.274, 35483–35491 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Andersen, M. D., Busk, P. K., Svendsen, I. & Møller, B. L. Cytochromes P-450 from cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) catalyzing the first steps in the biosynthesis of the cyanogenic glucosides linamarin and lotaustralin. Cloning, functional expression in Pichia pastoris, and substrate specificity of the isolated recombinant enzymes. J. Biol. Chem.275, 1966–1975 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jørgensen, K. et al. Biosynthesis of the cyanogenic glucosides linamarin and lotaustralin in cassava: isolation, biochemical characterization, and expression pattern of CYP71E7, the oxime-metabolizing cytochrome P450 enzyme. Plant Physiol.155, 282–292 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kannangara, R. et al. Characterization and expression profile of two UDP‐glucosyltransferases, UGT85K4 and UGT85K5, catalyzing the last step in cyanogenic glucoside biosynthesis in cassava. Plant J.68, 287–301 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Items

Data Availability Statement

The OneKP database is accessible at (ualberta.ca/onekp). The data from 120 SRA experiments are residing at NCBI as the fern whole genome duplication study with accession PRJNA422112. All other data are available in the main text or in the supplementary materials (Supplementary Data 1–3). Sequence data from this article can be found in the EMBL/GenBank data libraries under accession numbers MT856954 and MT856955 for the fern oxime synthase Paq18302 and Pa22578.

Details about software and algorithms used in this study are given in the “Methods” section. No customized code or algorithm deemed central to the conclusion was used.