Abstract

This article examines the use of social media, specifically Twitter, in crisis communications during a natural disaster and how it can provide information, guidance, reassurance and hope to victims while keeping others across the nation and the world apprised of the situation so they can provide assistance, as needed. A case study looks at how the mayor of Houston, Texas, Sylvester Turner, used Twitter during Hurricane Harvey in August and September of 2017. The case study is analyzed using restorative rhetoric theory, revealing the use of Twitter by Mayor Turner to be a strong example of successful restorative rhetoric during a natural disaster. This research affirms the findings of other researchers that the restorative rhetoric stages overlap, and that the theory may be improved with some variation based on crisis type. This research also shows that Mayor Turner's use of Twitter exemplifies best practices for using social media in crisis communications with very few opportunities for improvement. This article offers suggestions to crisis managers on how to use Twitter to prepare for, communicate during, and go forward following a natural disaster.

Keywords: Social science, Restorative rhetoric, Crisis communication, Natural disaster, Twitter, Social media, Hurricane Harvey

Social science; Restorative rhetoric; Crisis communication; Natural disaster; Twitter; Social media; Hurricane Harvey.

1. Introduction

Crises have been around for as long as man has walked the earth, but crisis communication has only been studied since the 1980s (Coombs, 2007). A crisis is a ‘major occurrence with a potentially negative outcome’ impacting an entity, such as a business, city, or a group of people, and its citizens, stakeholders, products, services or reputation (Fearn-Banks, 2017, p. 1). Crises are unexpected (Coombs, 2007; Hermann, 1963), pose a threat and require a quick response (Hermann, 1963; Seeger and Griffin Padgett, 2010; Ulmer et al., 2011). This is particularly true with natural disasters such as hurricanes, tsunamis, tornadoes, earthquakes and floods. They are often a surprise or have little warning, result in deaths, injuries and destruction, and require swift action to protect people and property. Communication is a ‘key emergency management and response activity’ throughout a crisis (Seeger and Griffin Padgett, 2010, p. 128). It is used to warn and prepare the public, provide needed information, coordinate first responders, reassure those impacted, help them understand the crisis, share information beyond those immediately impacted, and help those impacted move beyond the crisis (Seeger and Griffin Padgett, 2010).

Since the founding of Facebook in 2004 (Facebook, 2020) and Twitter in 2006 (Crunchbase, 2020), the rapid growth of social media has transformed the Internet by introducing the ability to have interactive dialogue (Kaplan and Haenlein, 2010). In fact, 82 percent of U.S. adults 18–49 years of age now use social media with 97 percent reporting they are online and 99 percent owning a smartphone (Pew Research Center, 2018). In recent years, social media has been used as a tool in crisis communications because it can assist with distributing aid and coordinating responders (Lachlan et al., 2015). Lachlan et al. (2015, p. 652) note that ‘social media can be advantageous in the face of crises as information and pleas for help can spread across the world in a matter of minutes.’ Twitter, in particular, is often referred to as the ‘most useful social media tool’ particularly for natural disasters (Liu et al., 2012, p. 362). However, social media is not yet used to its full potential in crisis communications (Lin et al., 2016) and more research is needed on social media and crisis communication (Eriksson and Olsson, 2016; Spence et al., 2016). The use of social media by crisis leaders is also an area in need of more examination. Crisis leaders are becoming more savvy in using social media tools to advance specific messaging, particularly during the recovery stage and the aftermath of a crisis when there is a greater need to realize a sense of normalcy.

This research explores how social media, particularly Twitter, can be used in a crisis to provide information, guidance, reassurance and hope to key publics through a case study examining the usage of Twitter by Houston, Texas mayor Sylvester Turner, during Hurricane Harvey in August and September of 2017. This article uses restorative rhetoric as a theoretical framework to analyze Mayor Turner's Twitter posts from the mayor's official Twitter account before, during and after the crisis. From this analysis, the article offers suggestions on how Twitter, and social media in general, can help crisis managers prepare for, communicate during, and move forward following a natural disaster.

2. Literature review

Crises can create pandemonium, particularly without coordinated first responders, thoughtful leadership and a focused recovery effort. While social media can make it easier to disseminate information to the public, this tool alone does not ensure successful management of a crisis, especially in the case of a natural disaster. These incidents require strong leadership and an application of best practices to mitigate harm and accelerate recovery. Ulmer et al. (2011) tell us that successful crisis managers listen to stakeholders and then create messages to meet their needs, focus on moving beyond the crisis rather than determining blame, are flexible and responsive, and, while crisis plans are helpful, it is crucial to develop positive relationships with stakeholders before a crisis. In the middle of a crisis, it's important for the crisis manager to provide updates on the crisis focusing on problem solving without being overly reassuring or attempting to spin the story to cover up problems (Ulmer et al., 2011). Public officials responsible for crisis communication need to provide accurate, prompt and useful information that assists victims and restores order (Seeger, 2006; Williams et al., 2017).

2.1. Crisis communication and social media

Most U.S. adults now use social media (Pew Research Center, 2018), making the use of social media a very viable option in crisis communication. Lachlan et al. (2015) showed that people are using Twitter and other social media during crises to share information and their reactions. It is also used for crisis preparations, raising environmental awareness, improving health, and determining public participation during environmental emergencies (Finch et al., 2016) as well as gaining volunteers and building relationships with them and the media (Liu et al., 2012). The use of social media can even result in coverage by ‘traditional media’ (Liu et al., 2012; Sutton et al., 2008; Veil et al., 2011).

Social media can enhance crisis response (Lin et al., 2016; Veil et al., 2011; Lachlan et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2017). During a crisis, problems with technology may reduce the ability of traditional media to reach the public, while social media may continue to be available (Shankar, 2008; Spence et al., 2015). Crises tend to increase the use of social media, often through use of a smartphone (Stokes and Senkbeil, 2016). While the public is increasingly relying on social media to find the latest information (Fox, 2011; Lachlan et al., 2014), most emergency managers are not experienced with using social media (Lachlan et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2016). Examples of recent crises that used social media include: The 2009 Red River Valley flood at the U.S.-Canadian border (Palen et al., 2010); the 2012 Hurricane Sandy (Wang and Zhuang, 2017); and the 2013 Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines (Takahashi et al., 2015).

Lin et al. (2016) offer seven best practices for using social media in crisis communication: (1) Fully integrate social media into decision-making and policy development; (2) Actively engage in dialogue online; (3) Use media affordances to provide credible sources of information; (4) Be cautious about message update speed; (5) Own the hashtag; (6) Cooperate with the public and similar organizations; and (7) Monitor misinformation. Veil et al. (2011) note that it is important to have a social media presence before a crisis which builds trust and allows the public to know where to look for information. Using social media to ask for help and give direction helps build a partnership with the community during the crisis (Veil et al., 2011). Liu et al. (2012) found that social media credibility is enhanced due to content, the affiliation of the individual posting the content, the number of followers for the individual posting the content, and whether the individual is trusted by the public. Monitoring social media is important to be aware of what is being said so inaccuracies can be corrected (Liu et al., 2012; Veil et al., 2011).

A robust body of work exists on social media usage. As more stakeholders seek out information about events and more journalists use social media content in the development of stories, scholars have begun to address the effects of social media, including its impact on public perceptions of leadership (Luo et al., 2015) and its impact on public behavior related to perceptions of risk (Spence et al., 2015).

2.2. Twitter and crisis communications

The Eriksson and Olsson study (2016) reported that citizens view Twitter as a tool to alert users in a crisis, find current events and locate news media coverage. That same study reports that Twitter is seen by some crisis managers as a tool for fast one-way information dissemination for decision makers and politicians, a way for users to find new trends and a quick way to reach the media. Wang and Zhuang (2017) analyzed tweets about Hurricane Sandy. They found that government organizations had a higher number of “likes” on their tweets (an average of 4.37 per tweet) than non-governmental organizations or news agencies (2.15 and 2.38 average likes, respectively). The number of “likes” are important because they measure the value readers place on the tweets. A retweet is reposting someone else's tweet (Twitter Help Center, 2020a). Retweeting helps to spread the tweet to individuals who do not normally follow the original author of the tweet. The more followers one has, the more a tweet can be retweeted (Wang and Zhuang, 2017). An impression is the frequency of a tweet displaying in the Twitter timeline or search results (Twitter Help Center, 2020b). Wang and Zhuang (2017) estimated that one retweet can contribute an average of 7,637 impressions.

Hashtags make Twitter a useful tool in crisis communication because hashtags allow users to gather all the tweets about a specific topic into one area making it easier to find breaking news and share with a wider group of readers interested in that topic (Eriksson, 2012; Eriksson and Olsson, 2016; Spence et al., 2015). Using locally named hashtags, such as #HoustonFlood instead of national hashtags like #Harvey, can help information get to the people who need it who might be overwhelmed by the volume of information associated with a national hashtag (Lachlan et al., 2015; Spence et al., 2015). Lachlan et al. (2015) found that messages from government agencies almost always were associated with local hashtags and that local hashtags were more likely to contain actionable and helpful information. Spence et al. (2015) studied tweets associated with the national hashtag #Sandy leading up to that hurricane in 2012. They found that most tweets were about ‘sorrow, anger and fear’ (p. 180) with less than eight percent of the tweets relaying useful information. In addition, this study found fewer usable tweets as the storm drew closer (Spence et al., 2015). Spence et al. (2016) assert that, since the pre-crisis stage is when most people need information (Fink, 1986), crisis managers should use Twitter to encourage people to be calm and offer specific actions to improve positive outcomes.

Bakker et al. (2019) found that when government crisis communications on Twitter display certainty, they engender trust in government. Receiving certain, rather than uncertain, information boosted recipients' certainty in their own judgment and made them more likely to use the information. In addition, an increase in certainty in one's own judgment was associated with increased self-reliance (Bakker et al., 2019; Rabinovich and Morton, 2012). Twitter has been successfully used to provide earthquake and tsunami warnings (Chatfield et al., 2013; Finch et al., 2016) and help first responders find areas in need quickly (Cassa et al., 2013; Finch et al., 2016).

2.3. Twitter and community resilience

Community resilience helps people respond to a crisis by being prepared through resources, risk reduction, community involvement, and planning but with the flexibility to make decisions in times of uncertainty (Norris et al., 2008). According to Zou et al. (2018), even a similar disaster type and level of threat can produce a different impact on a community based on the region and other elements like environmental factors (p. 1423). Community resilience scholarship focused on disaster studies has three tenets, including a community's capacity to withstand the force of a crisis event and still maintain functioning systems; a community's ability to self-organize in the wake of disaster; and its ability to “build the capacity to learn and adapt” (Zhang et al., 2015).

Information and communication are key ingredients in community resilience (Norris et al., 2008). Williams et al. (2017) explain that social media offers a sense of community. Indeed, according to Williams et al. (2017) providing fast and accurate information in a crisis helps to protect people and build community resilience. Using inclusive language, like ‘we’ and ‘our’ on Twitter helps to build resilience as well as promoting a shared purpose. The more resilient a group is, the faster it will return to normalcy after a crisis as resiliency facilitates rebuilding and can result in a community becoming stronger following a crisis (Veil and Bishop, 2014; Williams et al., 2017).

3. Theoretical framework

Natural disasters are a unique form of crisis. Unlike intentional crises that have a high level of responsibility attributed to the organization, such as organizational misconduct or a mistake causing product harm, natural disasters are victim crises with the lowest level of organizational responsibility (Coombs, 2007). This is because they are unintentional (Ulmer et al., 2011). As a result, the study of natural disasters does not lend itself well to theoretical frameworks that focus on repairing reputation such as William Benoit's image restoration or apologia (Benoit, 1995; Fearn-Banks, 2017; Seeger and Griffin Padgett, 2010; Ware and Linkugel, 1973).

Restorative rhetoric is a framework theorized by Griffin Padgett and Allison (2010) that was created specifically to explain “unique forms of crises that precipitate different responses” beyond concerns about public image, saving face and protecting market share (p. 377). The framework was designed to analyze “social crises” – or crises that place very unique demands on responders because of the widespread “public” nature of the response effort. In their analysis of Hurricane Katrina and the 911 terrorist attacks that brought the World Trade Center down, Griffin Padgett and Allison (2010) noted restorative rhetoric is necessary in crisis situations where there is much public debate, incidents that depend on coordinated efforts between crisis responders, and situations where the public's health and safety are concerns. According to its authors, these types of crises require two types of rhetorical responses: strategic, which involves communications that aim to reduce risk, strengthen public safety, and restore order, and humanistic, which involves communications focused on helping victims make sense of the crisis, heal emotionally and move toward the future (Griffin Padgett and Allison, 2010; Williams et al., 2017).

Restorative rhetoric assists victims as they move from crisis to recovery. In addition to the direct crisis victims, restorative rhetoric takes into account a larger audience that is impacted by the crisis (Griffin Padgett and Allison, 2010, p. 380). It also considers crisis communication to be dynamic, going back and forth between the steps rather than following them one after the other (Griffin Padgett and Allison, 2010). The five steps in restorative rhetoric are: (1) initial reaction; (2) assessment of the crisis; (3) issues of blame; (4) healing and forgiveness; and (5) corrective action and rebuilding through rhetorical vision (Griffin and Allison, 2007; Griffin Padgett and Allison, 2010; Williams et al., 2017). According to Griffin Padgett and Allison (2010), in the initial reaction stage the crisis is defined, sadness over the impact of the crisis is expressed along with statements about what can be done to control damage from the crisis. The second stage is when the damage from the crisis is assessed and the resources needed to handle the crisis are identified. The third stage involves issues of accountability and responsibility related to the incident. This may not be direct blame for the occurrence but may involve historical factors that contribute to the occurrence and accountability for the response effort. In the fourth stage, healing and forgiveness occur and the needs of victims are addressed. In the fifth and final stage, opportunities for rebuilding are explored and visions for the future are shared, often taking the community beyond the crisis to a higher level of learning and more meaningful recognition of what a community can accomplish.

While restorative rhetoric was used to explain Mayor Rudolph Giuliani's leadership during the World Trade Center terrorism event and Mayor Ray Nagin's leadership during Hurricane Katrina, both events were explained using traditional media (Griffin Padgett and Allison, 2010). Williams et al. (2017) used this theory to study Mayor Thomas Menino's leadership during the terrorism crisis of the Boston Marathon bombing using the mayor's posts on Twitter. This current study expands restorative rhetoric knowledge and its use within social media by analyzing communications taking place through Twitter for a natural disaster, specifically Mayor Sylvester Turner's rhetoric during the 2017 Hurricane Harvey crisis.

4. Case history

When Hurricane Harvey hit Texas in August 2017, it was a category 4, the second highest storm rating possible, with wind gusts up to 140 miles per hour (Achenbach and Rein, 2017; Lallensack, 2017). It ‘devastated a swath of Texas stretching from the Houston area into Louisiana,’ (Chokshi and Astor, 2017) dumping more than 50 inches — over four feet — of rain (Chokshi and Astor, 2017; FEMA, 2017; Mosher, 2017) and taking the lives of at least 82 people (Moravec, 2017). The area hit the hardest was Harris County, Texas, including the city of Houston (Mosher, 2017), an area that is home to 6.5 million people (City of Houston, 2017a). Houston is the fourth largest city in the U.S. It is just above sea level and is well known for flooding (Achenbach and Rein, 2017). What made Harvey more disastrous was that the storm stalled over Houston where it pounded the city and surroundings with rain, resulting in a ‘500-year flood’ that left thousands of people stranded on rooftops and homeless (Chokshi and Astor, 2017; Mosher, 2017).

The Coast Guard, FEMA's Urban Search and Rescue, the Department of Defense, the Civil Air Patrol, the Department of Transportation, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the American Red Cross, along with many other federal and private agencies assisted local first responders (FEMA, 2017). A FEMA news release (2017) summarized the devastation:

More than 19 trillion gallons of rainwater fell on parts of Texas, causing widespread, catastrophic flooding. Nearly 80,000 homes had at least 18 inches of floodwater, 23,000 of those with more than 5 feet. The Houston area experienced the largest amount of rainwater ever recorded in the continental United States from a single storm (51.88 inches). Twenty-four hospitals were evacuated, 61 communities lost drinking water capability, 23 ports were closed and 781 roads were impassable. Nearly 780,000 Texans evacuated their homes. In the days after the storm, more than 42,000 Texans were housed temporarily in 692 shelters. Local, state and federal first responders rescued 122,331 people and 5,234 pets.

The disaster also resulted in participation from local citizens and support from across the nation. For example, there weren't enough first responders available during the crisis, so many citizens jumped in, connecting through social media and rescuing others with private boats (Achenbach and Rein, 2017). As Jeff Balke, a Houstonian, reported (Balke, 2017):

There we were, Houstonians of every stripe, pulling strangers out of rising flood waters. The images of people of every color and economic background huddled together on flat-bottomed Jon boats and in the backs of trucks…no thought of anything but the desire to help. We became the example of how to live together, come hell or high water…

Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner maintained a steady stream of communication throughout the crisis through his Twitter account (https://twitter.com/sylvesterturner), providing crucial instructions, updates, reassurance and hope to the storm's victims and keeping others informed throughout the nation and the world. During the Hurricane Harvey crisis, Turner emerged as a dedicated, thoughtful, hard-working leader who put the needs of Houstonians ahead of all else. An analysis of the crisis communications distributed through Mayor Turner's Twitter account could offer guidance to other crisis managers and government leaders in future natural disasters.

5. Research question

This study examines Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner's Twitter communications during the Hurricane Harvey crisis through a restorative rhetoric lens to better understand how social media can be successfully used as a communication tool during a natural disaster.

6. Methods

A case study offers an opportunity to gain insight into a phenomenon (Thomas, 2016). Examining the details of a case can help us understand what worked well and what could have been improved, expanding knowledge of crisis communication for natural disasters, the use of restorative rhetoric and the use of Twitter during a crisis. This study used content analysis to examine the official Twitter account of Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner before, during and following Hurricane Harvey. This includes an examination of the content on Mayor Turner's Twitter page including all posts visible from August 23, 2017, two days before Hurricane Harvey hit landfall, through September 6, 2017, seven days after Harvey was downgraded to a tropical depression. August 23, 2017, was selected as the first day to study tweets on Hurricane Harvey because this is when Harvey was upgraded to a tropical depression in the Gulf of Mexico and became a concern for the City of Houston (National Weather Service, 2017).

The first 15 days of tweets were gathered by scrolling back on Twitter, taking screenshots of tweets and posting them in an Excel spreadsheet for further analysis. An additional eight days of top tweets were analyzed from September 7 through September 14, 2017, during the recovery phase. The tweets during these eight days were pulled from Twitter using Twitter's advanced search feature which provides top tweets rather than every tweet. In all, this research included 23 days of Twitter analysis.

The data were gathered and analyzed by the first researcher, who copied each post manually onto a spreadsheet by date. The tweet content was copied into the spreadsheet to allow for content searching and a screenshot of each tweet included graphics and a record of replies, retweets and likes. Each tweet was categorized based on the five stages of restorative rhetoric and a determination was made as to whether the content was strategic, humanistic, or both. The second researcher reviewed the analysis of the tweets and discussions between the two researchers were held to ensure inter-coder reliability.

Partway through the analysis additional categories were deemed helpful and added, including preparation, positivity, gratitude, and getting back to normal. A separate column was used to capture any links used in each tweet as well as a separate column for the use of hashtags. Additional columns were used to note if a tweet included Spanish language, whether it was a direct tweet or a retweet from another individual or organization, and whether the tweet was related to Hurricane Harvey or not. Each tweet was also identified as to whether it displayed one of the best practices for using social media in crisis communication as described by Lin et al. (2016). These additional best practice analysis points included whether the tweet showed integration into decision making and policy development, if inclusive language was used showing shared purpose, if the tweet showed engagement in online dialogue, if the tweet promoted credible sources or influential gatewatchers, if the tweet focused on handling rumors or misinformation, and whether the tweet was posted directly by Sylvester Turner or not (Mayor Turner clearly used ‘st’ at the end of each tweet that he made directly on his account.)

Data from the first level analysis were gathered into secondary spreadsheets to compare content and activity over the 23-day period. In all, 476 tweets were reviewed and analyzed. The second-level analysis included a list of all hashtags used and when they were used, a study of the percentage of tweets related to Hurricane Harvey during the time period, whether the tweet was direct, a retweet and whether it was posted by the mayor himself, strategic vs humanistic tweets, a view of which restorative rhetoric stage was represented over the course of the time period, whether inclusive language was used, credible sources were included and whether rumors were dispelled. Since this analysis was performed retrospectively, the authors already knew that the management of the crisis was considered successful given that the death toll was low compared to the devastation caused by the hurricane (Moravec, 2017). The challenge was to examine the communications according to restorative rhetoric theory and social media best practices to test if these tools could help explain the success of Mayor Turner's crisis communications and use this knowledge to help future emergency managers plan crisis communications during natural disasters.

7. Results

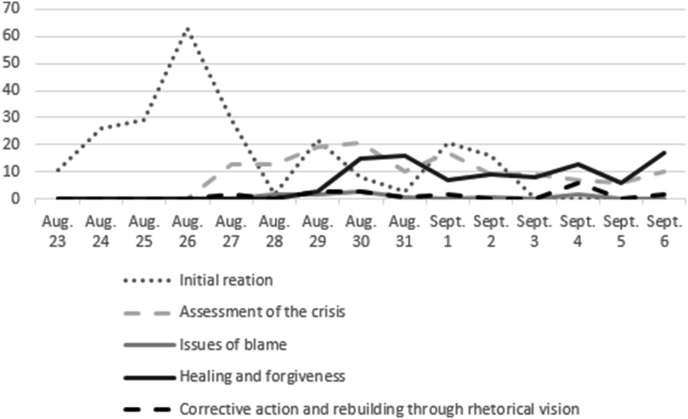

This study examined Mayor Turner's crisis communications through Twitter following the stages of restorative rhetoric. It's important to note that while the rhetorical content in general moved towards the last stage of corrective action and rebuilding as the crisis progressed, the content bounced between stages after the initial event occurred (Figure 1). This happened because there were two secondary crises, one on August 29 and the other on September 1. In each case, the secondary crisis rhetoric returned to the initial reaction stage to deal with the new crisis while the main crisis rhetoric continued to move through the standard stages. As Figure 1 shows, during the period covered by this study most of the rhetorical content was in the initial reaction, assessment of the crisis and healing and forgiveness stages.

Figure 1.

Number of tweets in restorative rhetoric stages in Mayor Turner's Hurricane Harvey Twitter communications.

7.1. Initial reaction – August 23, 2017

As reported by The Associated Press (2017), Harvey started as a tropical storm that faded but returned August 23 as a tropical depression, reaching hurricane status on August 24, 2017. Harvey didn't reach landfall until 10 p.m. on August 25, giving officials almost three full days to prepare for the storm. Mayor Turner took advantage of this time with half of his tweets on August 23 related to Harvey preparations, increasing to 93 and 97 percent respectively for tweets on August 24 and August 25. Beginning August 26, 100 percent of Mayor Turner's tweets were focused on the storm. This focus remained for eight days except for one unrelated tweet on August 30 about a federal ruling impacting local police.

The initial reaction stage includes defining the situation, expressing a level of control over damage through preparation and expressions of sorrow (Griffin Padgett and Allison, 2010). Mayor Turner's rhetoric throughout the crisis included a mix of both strategic and humanistic content, however, there were more strategic tweets with specific action steps at the beginning of the crisis (Griffin Padgett and Allison, 2010; Littlefield and Quenette, 2007; Seeger et al., 2003). Mayor Turner promoted the use of credible sources by telling residents where to find information, which is a social media best practice (Lin et al., 2016). The preparation tweets included retweets from official sources such as the Houston Office of Emergency Management, FEMA and Houston Police Chief Art Acevedo in both English and Spanish with tips for residents and information on how the city was preparing for the storm. Mayor Turner's earliest Harvey tweets urged residents to prepare, to remain calm and told them where to get updates. They also linked to video clips of Mayor Turner in local television interviews and fully televised city news conferences urging residents to remain calm but to be prepared and telling them what to do to get ready for the expected weather event.

Combating misinformation and correcting rumors is another best practice for the use of social media in crisis communications (Lin et al., 2016). Mayor Turner clearly showed this in his efforts to drive residents to official storm information, so they could receive trusted weather reports. On August 24 he tweeted, ‘Please do not get your information from Facebook. Refer to Houstonemergency.org.’ Mayor Turner also addressed the issue of evacuation repeatedly in the initial reaction stage to prevent confusion and dispel rumors. On August 25 he tweeted, ‘Please think twice before trying to leave Houston en masse. No evacuation orders have been issued for the city’ (Turner, 2017d).

The first full day after Hurricane Harvey hit landfall, August 26, 2017, had the highest number of tweets on Mayor Turner's Twitter account with 63 tweets that day, as compared to an average of 31 related tweets per day during the first two weeks of the crisis. Being cautious about message update speed is another social media best practice (Lin et al., 2016). Infrequent posts can get lost in the sea of posts coming through a person's Twitter feed. The average number of tweets per day is a little more than four per Twitter account (Cooper, 2019; Zarrella, 2016). Wang and Zhuang (2017) found that governmental organizations tweeted an average of 5.66 tweets over Hurricane Sandy's 16 days. Mayor Turner tweeted 263 direct tweets related to Hurricane Harvey (not counting retweets) over the 23 days of this study, for an average of 11.43 tweets per day. The message update speed displayed by Mayor Turner was far higher and more than adequate to get noticed by those needing the information and those following the crisis across the nation.

Media coverage included on Mayor Turner's Twitter account expanded from local to national on August 26 due to the size and strength of the storm. During this initial reaction stage of the crisis, Mayor Turner's tweets served as a source for guidance, reassurance and valuable information. He transparently shared information that residents needed, retweeting tornado warnings from the Houston Office of Emergency Management and the closure of schools, the airport, public transportation and specific roads. His tweets included requests for residents to stay home, but if they did have to go out he urged them to watch for flooded roads and #turnarounddontdrown. He also reported when bayous began flooding and shared when the first homes began to flood and the first shelters were opened. ‘There is rain and high water all over the City. Please stay put,’ (Turner, 2017f). Mayor Turner also retweeted live video from Police Chief Art Acevedo as he drove around the city so both residents and others outside the area could view the extreme weather from the safety of their homes. Recognizing a wider audience beyond those immediately impacted is a key component of restorative rhetoric (Griffin Padgett and Allison, 2010; Williams et al., 2017).

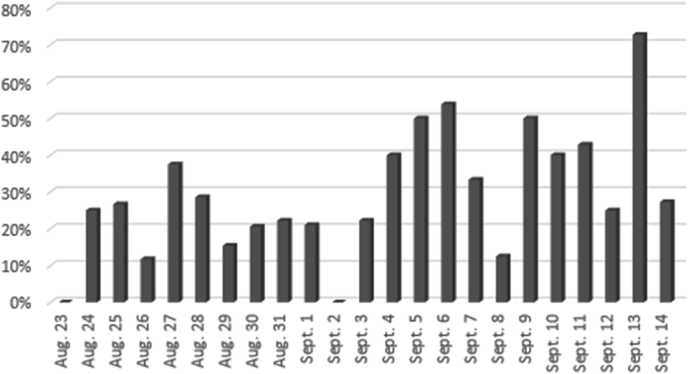

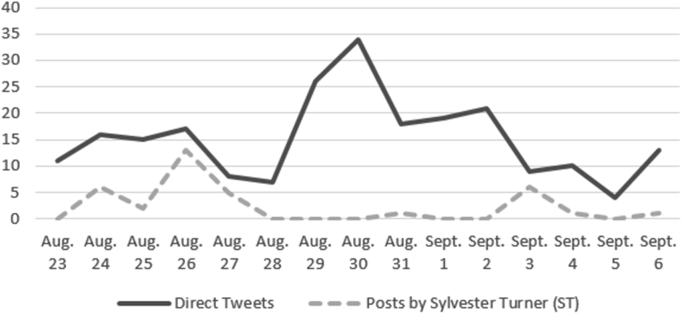

Mayor Turner used inclusive language throughout the crisis (examples in Figure 2). Using ‘we’ and ‘our’ helps to build community resilience and promote a shared purpose (Williams et al., 2017). The percentage of Mayor Turner's direct tweets that used inclusive language increased as the crisis moved into recovery (Figure 3). Determining the best methods for communicating to segmented publics is also important (Veil et al., 2011). Mayor Turner made sure some of his tweets and news conferences were in Spanish, and he always had a translator for the deaf and hearing impaired at news conferences.

Figure 2.

Examples of inclusive language.

Figure 3.

Percentage of tweets with inclusive language or shared purpose.

Figure 2 shows a post with an ‘st’ included at the end. This indicated that the post was written by Mayor Turner directly, rather than one of his staff. Doing this provides transparency and builds trust in Mayor Turner. Figure 4 shows the total direct tweets from Mayor Turner's account compared to the tweets posted directly by the mayor himself (those with an ‘st’.)

Figure 4.

Total direct tweets vs. tweets posted directly by Mayor Turner.

Houstonians reacted to Mayor Turner's tweets by commenting, retweeting and liking the Mayor's tweets. Of the 476 tweets analyzed for this paper, 263 tweets were direct tweets rather than retweets. Of these direct tweets, 107 (or 41%) had high levels of engagement, with over 100 comments, over 200 retweets or over 300 likes, or a combination of these. The initial reaction stage included the tweet that generated the highest number of comments, 594. This was a controversial tweet on August 25, asking citizens to not leave Houston, announcing that no evacuation orders had been issued. Mayor Turner's Twitter account has 125,700 followers, placing Mayor Turner's Twitter account as the third largest following amount U.S. mayors, behind only the Twitter accounts of the mayors of New York and Los Angeles. Most other mayoral Twitter accounts have followers in the 30,000 range.

7.2. Assessment of the crisis – August 27, 2017

The assessment of the crisis stage began August 27, with an assessment of the damage and identification of needs and resources (Griffin Padgett and Allison, 2010). Mayor Turner followed Lin et al. (2016) social media best practices by integrating Twitter into his crisis communication strategy. He did this by keeping Houstonians and the rest of the nation informed by tweeting links to news conferences and separate tweets with weather reports, data on the number of 911 calls and rescues of individuals in flooded areas, available shelters, tips on what to do if your home is flooding, and requests for specific donations and volunteer assistance.

The request for monetary donations began August 27 and was followed by many announcements of contributions including mega donations like $4 million from the Houston Astros, $10 million from the Houston Rockets, and $18 million from Walmart. On August 28, Mayor Turner tweeted a video of his visit to the largest shelter, the George R. Brown convention center, that was housing 5,000 homeless people at the time, later growing to 10,000. He thanked people for donations and put the crisis in perspective by saying, ‘They still have their lives. We can work together…and take things one day at a time’ (Turner, 2017a). In a news conference that was shared via Twitter later that day, Mayor Turner noted that the shelters were providing health care, medications, transportation for dialysis and everything needed. ‘This is a total care operation,’ Mayor Turner said (Turner, 2017e). He also combatted misinformation by reassuring citizens that the water was not impacted, and no papers were necessary to come to a shelter.

The tweets in the assessment of the crisis stage also had high citizen engagement with 40 tweets meeting or exceeding 100 comments, 200 retweets or 300 likes. The tweet with the most likes in this stage occurred on September 8 when Mayor Turner tweeted a photo of him touring a shelter with singer Janet Jackson (63 comments, 1,000 retweets and 2,700 likes). High engagement was also noted in tweets about the curfew (116 comments, 1,100 retweets and 1,900 likes) and Uber offering free rides to and from shelters (39 comments, 1,500 retweets and 1,900 likes).

7.3. Issues of blame – August 28, 2017

The issues of blame stage examines the cause and responsibility for the crisis occurrence and its response (Griffin Padgett and Allison, 2010). While there were no direct issues of blame associated with Hurricane Harvey, as it was a natural disaster, there was some blame and dissent over Mayor Turner's decision to refuse to order a mass evacuation. Mayor Turner used Twitter as his platform to respond to this and other controversial issues associated with his response. In tweets beginning August 28, and in a later news conference, Mayor Turner defended his decision to not evacuate the city by referencing how traffic before Hurricane Rita in 2005 resulted in many deaths from people stranded in flooding freeways. He also tweeted that zoning wouldn't have changed the flooding. Mayor Turner showed personal strength in his August 29 news conference where he said,

We are the fourth largest city in America. Harris county is the third largest county in the U.S. When you combine the two, there are over 6 million people. You cannot put them on the road when you don't know which way the storm is moving. It is absurd. I will let the talking heads talk, but they don't have responsibility for this city. I do. (City of Houston, 2017a)

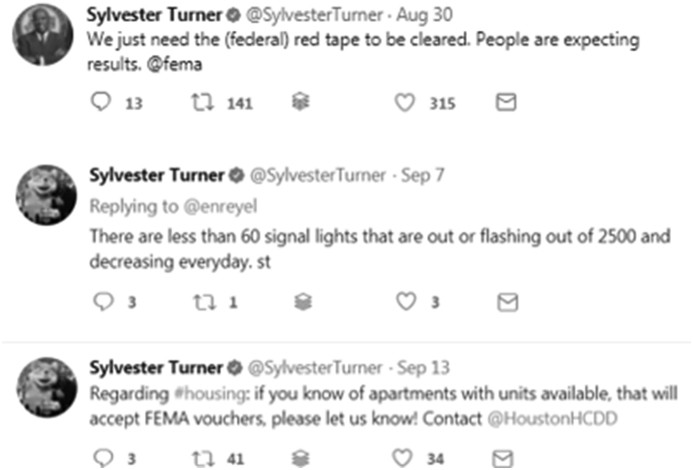

As previously mentioned, Mayor Turner's tweet about not evacuating the city generated 594 comments. Actively engaging in online dialogue is a social media best practice (Lin et al., 2016). Mayor Turner did this by reaching out to the community asking for their input, responding through Twitter, calling out to others using their Twitter user name (the @ symbol), and generating discussion with others commenting on his tweets. Some examples of online dialogue are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Examples of online dialogue.

While there were fewer tweets in the issues of blame stage, several of them garnered substantial citizen engagement. For example, a tweet on August 30 noting that people will evaluate how the recovery was handled referenced the Mayor's struggle with government funding, receiving 17 comments, 154 retweets and 545 likes. Another tweet on the same day, noted that zoning wouldn't have solved the flooding problem (26 comments, 135 retweets and 317 likes).

7.4. Healing and forgiveness – August 29, 2017

The healing and forgiveness stage helps victims handle the ramifications of the crisis by working through their issues (Griffin Padgett and Allison, 2010). This stage began on August 29 when Mayor Turner tweeted that ‘Houston will have the money to address the storm aftermath.’ He also acknowledged those impacted by the storm by tweeting that a moment of silence was held at the city council meeting for those affected. Part of the healing process was getting back to normal. Mayor Turner began announcing a return to normal on August 30 with the airport and public transportation reopening. ‘We are moving back into operation. It is my hope that despite how massive this storm has been, that the City of Houston will quickly move to get back to where we were and then even go beyond that,’ (City of Houston, 2017c). In an interview on Face The Nation shared on Mayor Turner's Twitter, Mayor Turner said, ‘This is a ‘can do’ city. We're not going to engage in a pity party. We're going to take care of each other,’ (Turner, 2017b). Mayor Turner showed his concern for Houstonians by tweeting health and safety tips and instructions for registering for FEMA assistance. The return of regular trash pickup and the reopening of the zoo, shipping channel and schools were each announced as victories in the healing of the city. He also tweeted positive statistics such as reductions in power outages and declining numbers in shelters. One of the big celebrations surrounded the return of baseball with Mayor Turner throwing the first pitch on September 2.

Own the hashtag is one of the social media best practices (Lin et al., 2016). Using a local hashtag is also important for making the tweets easier to find (Lachlan et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2016). This is because national hashtags may have many tweets unrelated to the local issues. Mayor Turner started out using the national hashtag #Harvey, but moved to regularly using local hashtags beginning September 1. The top local hashtags used to celebrate the return to normal were #HoustonRecovers, the shorter #HouRecovers and #HoustonStrong.

One of the two secondary crises happened on August 29 when the death of Police Sergeant Steve Perez was announced. Sergeant Perez drowned in his car trying to get to work on August 27, but dive teams did not find him until August 29. This was announced through a series of news conferences. This was devastating because Sergeant Perez was a first responder who died in the line of duty. This secondary crisis resulted in some rhetoric moving back to the initial reaction stage, explaining what happened, expressing sadness and describing actions citizens could take to reduce the likelihood of similar tragedies. After announcing the death of Sergeant Perez, Mayor Turner used rhetoric to help the community achieve healing and forgiveness.

They say this too shall pass. After the clouds pass the sun will shine. In this city, regardless of the storm clouds, regardless of the rain, in this city the sun will shine…Today we announced the death of Sergeant Steve Perez, and then on this day the sun came out. And I'm just going to say the good Lord did it in honor of Sergeant Perez to let us know that even in our worst moments there is still hope and we will still rise. (City of Houston, 2017c)

The healing and forgiveness stage had 36 tweets with high citizen engagement, with the highest responses coming from tweets referring to the return of professional baseball. One tweet on August 30, stating a desire for the Astros to play again received 71 comments, 957 retweets and 2,900 likes. Another tweet on September 6 with high engagement reported that crime was lower than before the storm (34 comments, 734 retweets and 2,300 likes).

7.5. Corrective action and rebuilding through rhetorical vision – August 27, 2019

The corrective action and rebuilding through rhetorical vision stage is when damage is repaired and the community achieves an improved level of existence (Griffin Padgett and Allison, 2010). As the crisis moved toward recovery more humanistic content helped to frame the event and promote renewal (Griffin Padgett and Allison, 2010; Littlefield and Quenette, 2007; Seeger et al., 2003). Mayor Turner first used rhetoric from the corrective action and rebuilding through rhetorical vision stage on August 27 when he tweeted, ‘This storm will not break our spirit. We are in this together and we will rebuild even greater together after #HurricaneHarvey.’ This tweet had the highest number of retweets and likes of any of Mayor Turner's tweets studied, with 256 comments, 3,600 retweets and 6,300 likes. If we consider Wang and Zhuang's (2017) assertion that one retweet can contribute an average of 7,637 impressions, Mayor Turner's tweet about rebuilding would have garnered over 48 million impressions.

Mayor Turner began regularly speaking about an improved future in a news conference on August 29 linked on Twitter, when he said,

Anyone who underestimates the spirit of this city, that person doesn't know Houston, doesn't know Houstonians. We are a tough bunch. We can fight with one another, but we are still family. We have a competitive spirit. Some say woe is Houston, but that will encourage us to work harder to say a year from now, look at the city now. (City of Houston, 2017c)

He reiterated this the following day saying, ‘We are a “can do” city. Doesn't matter the challenge, we believe we can do it. And if you challenge us, Houstonians are very competitive…I am very proud of this city,’ (City of Houston, 2017b).

During this period of rebuilding, another secondary crisis was announced September 1. Even though the sun returned on August 30 after five days of rain (Sternitzky-Di Napoli, 2017), Mayor Turner announced in a news conference that the continued release of water from bayous required by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was causing more neighborhoods to flood. This resulted in a situation where parts of the city were entering recovery with curfews lifted, while other parts remained in full crisis with initial reaction and crisis assessment occurring. Thus, on September 1 and 2, the bulk of Mayor Turner's tweets returned to the earlier stages of restorative rhetoric and rhetorical vision tweets did not return until September 4.

Mayor Turner made a lot of positive, encouraging statements about Houston's future. When the schools opened, Mayor Turner tweeted, ‘My mom used to say, “God gives the hardest exams to his best students.” After #Harvey, I encourage all our students to rise to the challenge,’ (Turner, 2017c). Since many vehicles were ruined by flood waters, Mayor Turner promoted the use of the city's public transportation. He also held a news conference on September 12 to introduce a video to promote the need for storm surge protection on the Gulf coast to prevent similar devastation in the future.

Cooperating with the public and other organizations is a social media best practice according to Lin et al. (2016). Throughout the crisis, Mayor Turner retweeted other mayors, organizations and prominent influential individuals from the local area and the nation. Some examples included former U.S. President Barack Obama, retired astronaut Scott Kelly who lives in Houston, Houston Rockets basketball player James Harden, local television reporter Sonia Gutierrez, Houston Chronicle sports columnist Brian T. Smith, Amber Mostyn, wife of a prominent local attorney and donor, and Floresta Stewart, a Houston Astros fan with many social media followers. Retweeting others promotes community cooperation and sharing, allowing individuals to participate in the conversation about the crisis (Lin et al., 2016).

Tweets with high citizen engagement in the corrective action and rebuilding through rhetorical vision stage included a statement about Houston rebuilding and winning again, like the Astros (baseball team) with 31 comments, 316 retweets and 1,100 likes. Although they didn't know it at the time of the tweet, the Astros would go on to win the World Series in 2017, further helping to heal the city devastated by Hurricane Harvey. Other tweets with high engagement included announcements that the convention center would soon be ready for visitors and suggestions that citizens try out public transit.

8. Discussion

While other research has studied crisis management with a natural disaster using traditional media (Griffin Padgett and Allison, 2010) and a terrorism crisis using social media (Williams et al., 2017), this is the first study applying restorative rhetoric with a natural disaster using social media. This analysis shows Mayor Turner's use of Twitter during the Hurricane Harvey crisis to be a good example of successful use of restorative rhetoric in a natural disaster. The communications included a mix of strategic and humanistic rhetoric (Griffin Padgett and Allison, 2010; Williams et al., 2017) with an emphasis on strategic communications in the initial reaction stage with specific instructions to reduce risk and improve public safety, as this was crucial to saving lives. After the hurricane hit, Mayor Turner incorporated more humanistic rhetoric to help citizens understand what had happened, help them heal and provide them with a vision for the future. Mayor Turner's Twitter account focused on the needs of the local community, but also kept the nation and the world apprised of the situation. Including the larger audience beyond those directly impacted by the crisis is an important aspect of the response effort (Griffin Padgett and Allison, 2010; Williams et al., 2017). In this case, it helped with gathering donations of funding, resources and volunteers to assist those impacted.

A leader's response is essential to the management of a crisis, particularly after a natural disaster where the threat to human life is heightened. What is unique about this response is not only the use of social media to communicate with stakeholders about the extent of damage and recovery efforts, but also to promote a sense of unity. Mayor Turner's tweets revealed a set of key messages, including “we're in this together” and “stay safe” in the wake of his order that residents stay put and ride out the storm. Officials didn't know exactly where the hurricane would make landfall and no one wanted a repeat of the tragic losses in the aftermath of Hurricane Rita, where “dozens of people died on the road – in a horrific bus fire, in traffic accidents, and of heat stroke” (Dononoske, 2017). Turner's approach was similar to former New Orleans mayor Ray Nagin after Hurricane Katrina. He remained highly visible as the days after the crisis turned into weeks and assured his residents that he would make sure that everyone was rescued, building trust and offering hope. He also appealed to residents' sense of humanity by focusing them on helping each other until help arrived. His communication triggered a sense of community as support for the recovery effort came in many forms, including charitable events to support the recovery effort and positive messaging on Twitter. Mayor Turner's Twitter account engaged readers as shown by their responses to his tweets. An analysis of the direct tweets related to Hurricane Harvey (removing retweets) during this study period shows an average of 20 comments, 216 retweets and 447 likes per tweet.

This research confirms what Williams et al. (2017) found, that the stages of restorative rhetoric are not sequential and overlap. In fact, this research found that after the crisis hit, there were tweets categorized in the initial reaction, assessment of the crisis and healing and forgiveness stages all in the same day. While the content generally moved toward the last stage of corrective action and rebuilding, the content often moved between stages, particularly when secondary crises occurred that moved the rhetoric, at least temporarily, back to the initial reaction stage. This happened twice during Hurricane Harvey, with the death of a first responder and the release of water from bayous that flooded areas not impacted earlier in the crisis. Mayor Turner handled each of these secondary crises well by explaining the situation, expressing sorrow and providing guidance to protect citizens and their property.

This study also confirms the Williams et al. (2017) assertion that the application of this theory may vary depending on the crisis. In a natural disaster, there is no one to blame, so the issues of blame stage becomes less important unless there are concerns about the way the crisis was managed, as there were with Hurricane Katrina (Griffin Padgett and Allison, 2010). Hurricane Harvey was a weather event for which no one was to blame. Crisis response was handled well with cooperation between government entities and the community resulting in rescues, shelters and resources saving many lives. As a result, forgiveness was not needed in this crisis. The only controversy discussed during this crisis was whether the city should have been evacuated. Mayor Turner defended his position that citizens were safer staying at home and he backed that up with statistics from Hurricane Rita which resulted in more deaths from individuals who drowned in their cars trying to exit the city. Mayor Turner's explanation resolved the concern and allowed rhetoric to focus on the needs of the community rather than blame.

This research found a huge focus on positivity, gratitude and returning to normal with many examples exhibited in Mayor Turner's tweets. Because of their prevalence, they were added as specific items tracked during the content analysis. Statements of positivity, gratitude and returning to normal began during the assessment of the crisis stage and continued as the city moved into the corrective action and rebuilding through rhetorical vision stage. These themes were key to Mayor Turner's rhetoric. Throughout the crisis, Mayor Turner's positivity gave the community hope that they could get through the storm. He also continually expressed gratitude to the first responders, to citizens who heeded curfews, to volunteers who offered their services or brought food, clothing and necessities to the shelters, and to donors who responded with funding to help the city meet the needs of storm victims and rebuild. Tweets focusing on returning to normal began August 30. Since most services and businesses across the city had shut down during the hurricane, the reopening of each was celebrated as a success. As a result, for natural disasters, the healing and forgiveness stage of restorative rhetoric may be better named healing, expressions of positivity and gratitude, and returning to normal.

Preparation may also benefit from being recognized as a full stage in restorative rhetoric for natural disasters. Unlike many acts of terrorism, in some natural disasters like Hurricane Harvey, there is some forewarning and the opportunity to take precautions before the crisis hits. When preparation is possible, it may be better served as its own stage in the theory, so it can be studied separately from the initial reaction. In the example of Hurricane Harvey, preparation tweets offered warnings of the approaching storm, reminded residents about what to do in case of an emergency and offered tips on preparation, such as stocking an emergency kit, updating emergency contacts on cell phones, making sure the car has gas, checking on neighbors, following only trusted sources for information, and staying away from flooded areas.

Mayor Turner's Twitter communications exemplified each of the best practices for the use of social media in crisis communications as recommended by Lin et al. (2016). The flow of information through the Twitter account studied exceeded average communication levels markedly – with more than seven times the average number of posts on a Twitter account. This high rate of message update speed helped impart necessary information to the community (Lin et al., 2016). Mayor Turner already had a presence within social media and Twitter prior to the crisis, so the community knew where to look for information (Ulmer et al., 2011; Veil et al., 2011). The Mayor's office clearly incorporated social media into their crisis management processes with adequate staffing to maintain high levels of communication. They ensured that all news conferences were linked from the Twitter account and used the medium to listen and respond to community concerns and dispel rumors (Lin et al., 2016; Veil et al., 2011).

Mayor Turner's account also retweeted many credible sources during the crisis, such as the Houston Office of Emergency Management, the Chief of Police Art Acevedo and the City of Houston (Lin et al., 2016; Veil et al., 2011). This meant that Mayor Turner's Twitter followers could use his Twitter account as their main source for trusted information. Mayor Turner also retweeted from influential gatekeepers such as former President Barack Obama, local sports stars and other prominent citizens, allowing the community to participate in the conversation (Lin et al., 2016). In addition, he made sure to communicate to segmented publics (Veil et al., 2011) including Spanish speaking and deaf and hearing-impaired residents, and he built trust through transparency by adding his initials to personally-written tweets.

There were a few opportunities for improvement based on Lin's best practices (2016), including the use of hashtags and inclusive language. Mayor Turner's Twitter account used the national hashtag #Harvey at the beginning of the crisis and daily through September 3. #Harvey was the most used hashtag on Mayor Turner's Twitter account during the period studied. While Mayor Turner's Twitter first used a local hashtag, #Houston, August 25, regular uses of a local hashtag didn't begin until September 1, when #HoustonRecovers and #HoustonStrong began to be used. Local hashtags would have been useful at the beginning of the crisis as they help local community members find the information they need without sorting through national comments about the topic (Lachlan et al., 2015; Spence et al., 2015). Understanding that the national hashtag helps the larger national audience find and follow the crisis, and may have helped boost donations of funding, goods and volunteers, including both local and national hashtags would have blended the needs of the local citizens with the need to keep the nation informed.

The use of inclusive language in Mayor Turner's Twitter, such as ‘we’ and ‘our’, should have been increased. While inclusive language was evident throughout the crisis, it was more prevalent as the crisis moved into recovery and would have been helpful in the early days of the crisis to help build community resilience. For instance, rather than this tweet from August 24, ‘What you can do is minimize your traveling this weekend and avoid intersections in streets that you know flood and exercise common sense’ (Turner, 2017g), the tweet could have been reworded to be more inclusive by saying, ‘Houstonians, we must minimize our travel this weekend and avoid intersections in streets we know flood and exercise common sense.’ The use of ‘we’ and ‘our’ communicates a shared experience, builds relationships and offers a sense of community (Klann, 2003; Williams et al., 2017).

9. Conclusion

The study of Mayor Turner's communications through his Twitter account during the Hurricane Harvey crisis improves our understanding of the use of restorative rhetoric with natural disasters. This study also suggests that some revisions to the theory of restorative rhetoric may be beneficial when used with natural disasters. First, the issues of blame stage is less important with natural disasters unless there are concerns about how the crisis manager handles the situation. Second, the healing and forgiveness stage may benefit from being renamed healing, expressions of positivity and gratitude, and returning to normal. Finally, the addition of a preparation stage would allow for more focus on the period before the crisis hits, a phenomenon that is applicable to natural disasters but not acts of terrorism.

Examining how Mayor Turner's use of Twitter during Hurricane Harvey met social media best practices for crisis communications (Lin et al., 2016; Veil et al., 2011) offers suggestions to emergency managers and government leaders on how to improve their use of social media in times of crisis. This study shows the importance of having an established social media account before the crisis and having adequate staffing to provide frequent messaging so the community can find the information they need within the sea of tweets. It also shows the importance of incorporating social media into the communications strategy and linking to all news conferences from social media. In addition, using social media to listen and respond to the community, dispel rumors and correct inaccurate information, helping the community find credible sources of information, and participating with other influential citizens on social media to widen the conversation were all key elements to managing the crisis successfully. Using inclusive language, such as ‘we’ and ‘our’ to promote a sense of community, translating communications to specific languages needed by the community, and building trust by indicating when a tweet is written by the person whose name is on the account were also important, as were incorporating both local and national hashtags throughout the crisis to meet the needs of both the local citizens directly impacted as well as interested individuals across the nation and world who may be willing to offer assistance. In the case of Hurricane Harvey, Mayor Turner did an exemplary job of communicating through Twitter but could have included more tweets with inclusive language and more local hashtags earlier in the crisis.

This research only covers the first 23 days of the Hurricane Harvey crisis. Additional research would be helpful to examine more fully the corrective action and rebuilding through rhetorical vision stage which covered many months beyond the period studied for this paper. Additional research looking at the #Harvey hashtag communications could also help explain how easy or difficult it may have been to locate the initial tweets from Mayor Turner during this crisis. It would also be helpful to study how many of the donors and volunteers who stepped in to help after the crisis did so at least partially due to hearing about the crisis through social media. Extending our knowledge of the use of social media in crisis communication could offer guidance to crisis managers in preparing for, communicating during, and moving forward following future natural disasters.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

C. Vera-Burgos: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

D. G. Padgett: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Contributor Information

Catherine M. Vera-Burgos, Email: df3536@wayne.edu, cathy@vbfamily.com.

Donyale R. Griffin Padgett, Email: drpadge@wayne.edu.

References

- Achenbach J., Rein L. FEMA director says Harvey is probably the worst disaster in Texas history. Wash. Post. 2017 https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/fema-director-says-harvey-is-probably-the-worst-disaster-in-texas-history/2017/08/27/ef01600a-8b3f-11e7-8df5-c2e5cf46c1e2_story.html?utm_term=.f7bdd15aa797 August 27, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker M., van Bommel M., Kerstholt J.H., Giebels E. The interplay between governmental communications and fellow citizens’ reactions via twitter: experimental results of a theoretical crisis in The Netherlands. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2019;27(3):265–271. [Google Scholar]

- Balke J. How hurricane Harvey taught the world about Houston. Houston Press. 2017 http://www.houstonpress.com/arts/hurricane-harvey-taught-the-world-about-houston-9766973 September 7, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit W.L. State University of New York Press; Albany, NY: 1995. Accounts, Excuses and Apologies. [Google Scholar]

- Cassa C.A., Chunara R., Mandl K., Brownstein J.S. Twitter as a sentinel in emergency situations: lessons from the Boston Marathon explosions. PLOS Currents Disasters. 2013 doi: 10.1371/currents.dis.ad70cd1c8bc585e9470046cde334ee4b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatfield A.T., Scholl H.J., Brajawidagda U. Tsunami early warnings via Twitter in government: net-savvy citizens’ co-production of time-critical public information services. Govern. Inf. Q. 2013;30:377–386. [Google Scholar]

- Chokshi N., Astor M. Hurricane Harvey: the devastation and what comes next. The New York Times. 2017 https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/28/us/hurricane-harvey-texas.html Aug. 28, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- City of Houston . 2017. #Harvey Update [video File]https://www.pscp.tv/houstontxdotgov/1YpKkmmqQaPJj?t=215 August 29, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- City of Houston . 2017. Mayor’s #Harvey Update W/special Announcement from @Walmart [video File]https://www.pscp.tv/houstontxdotgov/1LyGBEEXlbEKN?t=49 August 30, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- City of Houston . 2017. Update on #Harvey [video File]https://www.pscp.tv/houstontxdotgov/1RDxlmmdgNoKL?t=325 August 29, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs W.T. Attribution Theory as a guide for post-crisis communication research. Publ. Relat. Rev. 2007;33(2):135–139. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper P. 2019. 28 Twitter Statistics All Marketers Need to Know in 2019. Hootsuite.https://blog.hootsuite.com/twitter-statistics/ Jan. 16, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Crunchbase . 2020. Twitter.https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/twitter#section-overview Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Dononoske C. 2017. Why Didn’t Officials Order the Evacuation of Houston? NPR.https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/08/28/546721363/why-didn-t-officials-order-the-evacuation-of-houston August 28, Retrieved online June 24, 2020 from. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson M. On-line strategic crisis communication: in search of a descriptive model approach. Int. J. Strat. Commun. 2012;5(4):309–327. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson M., Olsson E. Facebook and twitter in crisis communication: a comparative study of crisis communication professionals and citizens. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2016;24(4):198–208. [Google Scholar]

- Facebook . 2020. Newsroom.https://newsroom.fb.com/company-info/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Fearn-Banks K. fifth ed. Routledge; New York, NY: 2017. Crisis Communications: A Casebook Approach. [Google Scholar]

- FEMA . 2017. Historic Disaster Response to Hurricane Harvey in Texas.https://www.fema.gov/news-release/2017/09/22/historic-disaster-response-hurricane-harvey-texas September 22, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Finch K.C., Snook K.R., Duke C.H., Fu K., Tse Z.T., Adhikari A., Fung I.C. Public health implications of social media use during natural disasters, environmental disasters, and other environmental concerns. Nat. Hazards. 2016;83:729–760. [Google Scholar]

- Fink S. AMACOM; New York: 1986. Crisis Management: Planning for the Inevitable. [Google Scholar]

- Fox S. The social life of health information, 2011. Pew Research Center Internet & Technology. 2011 http://www.pewinternet.org/2011/05/12/the-social-life-of-health-information-2011/ May 12, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin D.R., Allison D. Paper Presented at the Annual Conference of the Eastern Communication Association, Providence, RI. 2007, April. Making a case for restorative rhetoric: a comparative analysis of Mayor Ray Nagin and Rudolph Giuliani’s response to disaster. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin Padgett D.R., Allison D. Making a case for restorative rhetoric: mayor Rudolph Giuliani & mayor Ray Nagin’s response to disaster. Commun. Monogr. 2010;77(3):376–392. [Google Scholar]

- Hermann C.F. Some consequences of crisis which limit the viability of organizations. Adm. Sci. Q. 1963;8:61–82. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan A.M., Haenlein M. Users of the world, unite! the challenges and opportunities of social media. Bus. Horiz. 2010;53(1):59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Klann G. 2003. Crisis Leadership: Using Military Lessons, Organizational Experiences, and the Power of Influence to Lessen the Impact of Chaos on the People You Lead [E-Reader Version]https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/wayne/reader.action?docID=3007579&ppg=7 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Lachlan K.A., Spence P.R., Lin X., Del Greco M. Screaming into the wind: twitter use during hurricane Sandy. Commun. Stud. 2014;65(5):500–518. [Google Scholar]

- Lachlan K.A., Spence P.R., Lin X., Najarian K., Del Greco M. Social media and crisis management: CERC, search strategies, and Twitter content. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015;54:647–652. [Google Scholar]

- Lallensack R. Hurricanes Harvey and Irma send scientists scrambling for data. International weekly journal of science. 2017;549(7673):439–440. doi: 10.1038/549439a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X., Spence P.R., Sellnow T.L., Lachlan K.A. Crisis communication, learning and responding: best practices in social media. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016;65:601–605. [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield R.S., Quenette A.M. Crisis leadership and Hurricane Katrina: the portrayal of authority by the media in natural disasters. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2007;35(1):26–47. [Google Scholar]

- Liu B.F., Jin Y., Briones R., Kuch B. Managing turbulence in the blogosphere: evaluating the blog-mediated crisis communication model with the American red Cross. J. Publ. Relat. Res. 2012;24:353–370. [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y., Jiang H., Kulemeka O. Strategic social media management and public relations leadership: insights from industry leaders. Int. J. Strat. Commun. 2015;9(3):167–196. [Google Scholar]

- Moravec E.R. Texas officials: hurricane Harvey death toll at 82, ‘mass casualties have absolutely not happened’. Wash. Post. 2017 https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/texas-officials-hurricane-harvey-death-toll-at-82-mass-casualties-have-absolutely-not-happened/2017/09/14/bff3ffea-9975-11e7-87fc-c3f7ee4035c9_story.html?utm_term=.329c0ba85637 September 14, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Mosher D. The crucial reason Houston officials didn’t order evacuations before Harvey made landfall. Business Insider. 2017 http://www.businessinsider.com/hurricane-evacuations-traffic-jam-drowning-deaths-2017-8 August 31, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- National Weather Service . 2017. Hurricane Harvey & its Impacts on Southeast Texas (August 25-29, 2017)https://www.weather.gov/hgx/hurricaneharvey Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Norris F.H., Stevens S.P., Pfefferbaum B., Wyche K.F., Pfefferbaum R.L. Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008;41(1-2):127–150. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palen L., Starbird K., Vieweg S., Hughes A. Twitter-based information distribution during the 2009 Red River Valley flood threat. Bull. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2010;36(5):13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center . 2018. Internet, Social media Use and Device Ownership in U.S. Have Plateaued after Years of Growth.https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/09/28/internet-social-media-use-and-device-ownership-in-u-s-have-plateaued-after-years-of-growth/ September 28, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovich A., Morton T.A. Unquestioned answers or unanswered questions: beliefs about science guide responses to uncertainty in climate change risk communication. Risk Anal. 2012;32(6):992–1002. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2012.01771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeger M.W. Best practices in crisis communication: an expert panel process. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2006;34(3):232–244. [Google Scholar]

- Seeger M.W., Griffin Padgett D.R. From image restoration to renewal: approaches to understanding postcrisis communication. Rev. Commun. 2010;10(2):127–141. [Google Scholar]

- Seeger M.W., Sellnow T.L., Ulmer R.R. Praeger Publishers; Westport, CT: 2003. Communication and Organizational Crisis. [Google Scholar]

- Shankar K. Wind, water, and wi-fi: new trends in community informatics and disaster management. Inf. Soc. 2008;24(2):116–120. [Google Scholar]

- Spence P.R., Lachlan K.A., Lin X., del Greco M. Variability in twitter content across the stages of a natural disaster: implications for crisis communication. Commun. Q. 2015;63(2):171–186. [Google Scholar]

- Spence P.R., Lachlan K.A., Rainear A.M. Social media and crisis research: data collection and directions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016;54:667–672. [Google Scholar]

- Sternitzky-Di Napoli D. Hurricane Harvey timeline for those who don’t know what day it is. Houst. Chron. (Houst. TX) 2017 http://www.chron.com/news/houston-weather/hurricaneharvey/article/Hurricane-Harvey-timeline-12169265.php#photo-13818477 September 2, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes C., Senkbeil J.C. Facebook and Twitter, communication and shelter, and the 2011 Tuscaloosa tornado. Disasters. 2016;41(1):194–208. doi: 10.1111/disa.12192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton J., Palen L., Shklovski I. Proceedings of the 5th International ISCRAM Conference, Washington, DC. 2008. Backchannels on the front lines: emergent uses of social media in the 2007 Southern California wildfires. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi B., Tandoc E.C., Jr., Carmichael C. Communicating on twitter during a disaster: an analysis of tweets during Typhoon haiyan in the phillipines. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015;50:392–398. [Google Scholar]

- The Associated Press . 2017. The Latest: Texas Cities Start Assessing hurricane Damage.http://broadstripe.net/news/read/article/the_associated_press-the_latest_hurricane_harvey_strengthens_off_texas-ap August 26, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas G. Sage Publications Ltd; London: 2016. How to Do Your Case Study.https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=CMiICwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=case+study+method&ots=ykOzFqlwBV&sig=j6inOv2d9tHRo3-oeKawWXiXmvQ#v=onepage&q=case%20study%20method&f=false Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Turner S., SylvesterTurner . 2017. Greeting Houstonians at @GRBCC [video File]https://www.pscp.tv/SylvesterTurner/1LyxBEEVRnpJN?t=133 August 28, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Turner S., SylvesterTurner . 2017. In My Interview with @FaceTheNation, I Mentioned How #Houston Is a ‘can Do’ City and that We Are Open for #business [Tweet] [Video File]https://twitter.com/twitter/statuses/904333845830434816 September 3, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Turner S., SylvesterTurner . 2017. My Mom Used to Say ‘God Gives the Hardest Exams to His Best students.’ after #Harvey, I Encourage All Our Students to Rise to the challenge [Tweet]https://twitter.com/SylvesterTurner September 11, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Turner S., SylvesterTurner . 2017. Please think twice before trying to leave Houston en masse. No evacuation orders have been issued for the city. #Harvey [Tweet]https://twitter.com/SylvesterTurner August 25, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Turner S., SylvesterTurner . 2017. Press Conference at @GRBCC [video File]https://www.pscp.tv/SylvesterTurner/1OdJrookXDexX?t=181 August 28, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Turner S., SylvesterTurner . 2017. There Is Rain and High Water All over the City. Please Stay put.-st [Tweet]https://twitter.com/SylvesterTurner August 26, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Turner S., SylvesterTurner . 2017. What You Can Do Is Minimize Your Traveling This Weekend and Avoid Intersections in Streets that You Know Flood and Exercise Common Sense. St [Tweet]https://twitter.com/SylvesterTurner August 24, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Twitter Help Center . 2020. Retweet FAQs.https://help.twitter.com/en/using-twitter/retweet-faqs#:∼:text=A%20Retweet is a re,re%2Dposting someone else's content Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Twitter Help Center . 2020. About Your Activity Dashboard.https://help.twitter.com/en/managing-your-account/using-the-tweet-activity-dashboard Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Ulmer R.R., Sellnow T.L., Seeger M.W. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2011. Effective Crisis Communication: Moving from Crisis to Opportunity. [Google Scholar]

- Veil S.R., Bishop B.W. Opportunities and challenges for public libraries to enhance community resilience. Risk Anal. 2014;34:721–734. doi: 10.1111/risa.12130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veil S.R., Buehner T., Palenchar M. A work in-process literature review: incorporating social media in risk and crisis communication. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2011;19:110–122. [Google Scholar]

- Ware B.L., Linkugel W.A. They spoke in defense of themselves: on the generic criticism of apologia. Q. J. Speech. 1973;59(3):273–283. [Google Scholar]

- Williams G.A., Woods C.L., Staricek N.C. Restorative rhetoric and social media: an examination of the Boston Marathon bombing. Commun. Stud. 2017;68(4):385–402. [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Zhuang J. Crisis information distribution on Twitter: a content analysis of tweets during Hurricane Sandy. Nat. Hazards. 2017;89:161–181. [Google Scholar]

- Zarrella D. Is 22 tweets-per-day the optimum? HubSpot. 2016 https://blog.hubspot.com/blog/tabid/6307/bid/4594/Is-22-Tweets-Per-Day-the-Optimum.aspx Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Drake W., Li Y., Zobel C., Cowell M. Proceedings of the ISCRAM 2015 Conference, Kristiansand. 2015. Fostering community resilience through adaptive learning in a social media age: municipal Twitter use in New Jersey following Hurricane Sandy.http://idl.iscram.org/files/yangzhang/2015/1236_YangZhang_etal2015.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Zou L., Lam N., Cai H., Qiang Y. Mining Twitter data for improved understanding of disaster resilience. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2018;108(5):1422–1441. [Google Scholar]