Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic is causing a catastrophic increase in US mortality. How does the scale of this pandemic compare to another US catastrophe: racial inequality? Using demographic models, I estimate how many excess White deaths would raise US White mortality to the best-ever (lowest) US Black level under alternative, plausible assumptions about the age patterning of excess mortality in 2020. I find that 400,000 excess White deaths would be needed to equal the best mortality ever recorded among Blacks. For White mortality in 2020 to reach levels that Blacks experience outside of pandemics, current COVID-19 mortality levels would need to increase by a factor of nearly 6. Moreover, White life expectancy in 2020 will remain higher than Black life expectancy has ever been unless nearly 700,000 excess White deaths occur. Even amid COVID-19, US White mortality is likely to be less than what US Blacks have experienced every year. I argue that, if Black disadvantage operates every year on the scale of Whites’ experience of COVID-19, then so too should the tools we deploy to fight it. Our imagination should not be limited by how accustomed the United States is to profound racial inequality.

Keywords: racial inequality, mortality, COVID-19

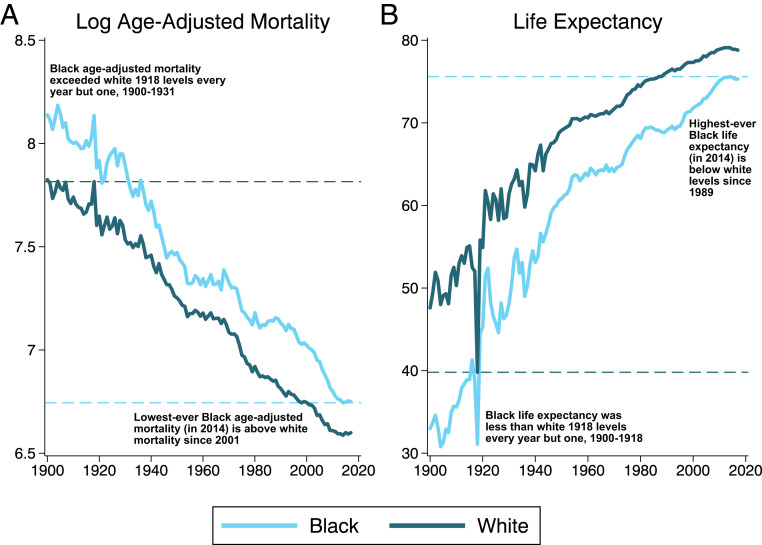

The COVID-19 pandemic is likely to kill people in the United States on a scale not seen in a century, since the 1918 flu. That catastrophic flu killed tens of millions worldwide and over half a million in the United States. Yet mortality levels that, for White Americans, were unprecedented nevertheless were lower than mortality for US Blacks in any given (nonpandemic) year. Past research has shown that the infectious mortality experienced by urban Whites in 1918 was lower than the infectious mortality of urban nonwhites in every documented year through 1920 (1). Fig. 1 shows that a similar pattern pertains to Whites’ and Blacks’ age-adjusted total mortality and life expectancy. Whites’ life expectancy in 1918 was far lower than in other twentieth century years—yet higher than Black life expectancy in all years but one between 1900 and 1918. Similarly, Whites’ age-adjusted mortality in 1918 was lower than Black mortality in all years but one from 1900 to 1931. By all major mortality measures—infectious mortality, total mortality, and life expectancy—in the early decades of the twentieth century, Blacks in the United States experienced a scale of death comparable to Whites’ experience of the 1918 flu every year.

Fig. 1.

US Black and White (A) logged deaths per 100,000 and (B) life expectancy, 1900–2017.

A century later, stark inequalities in survival persist. Will graphs of the early twenty-first century look like graphs of the early twentieth century, with a deadly pandemic causing a spike in mortality for Whites that nevertheless remains lower than the mortality Blacks experience routinely, outside of any pandemic? This question cannot be answered definitively until the final toll of COVID-19 is known. As a framework for answering it, I estimate how many White deaths from COVID-19 would be required for White mortality in 2020 to reach the levels of Black mortality in its best recorded year.

The results provide context for understanding the scale of racial inequality in mortality in the United States. Despite recent scholarly focus on rising White mortality (2), that racial inequality remains extreme. As Fig. 1 underscores, best-ever Black age-adjusted mortality and life expectancy are equivalent to White rates from, respectively, nearly 20 or 30 y earlier. For COVID-19 to raise mortality as much as racial inequality does, it would need to erase two to three decades of mortality progress for Whites.

Results

I used official US life tables (3) and demographic models to estimate how many additional deaths due to COVID-19 would be required for age-adjusted, non-Hispanic White mortality in 2020 to rise to the minimum recorded age-adjusted, non-Hispanic Black mortality, and, similarly, how many additional deaths would be required for non-Hispanic White mortality to fall to the highest recorded Black life expectancy. Mortality comparisons between Blacks and Whites require age standardization (4) because Whites are older than Blacks (median age 43 y vs. 33 y). The estimates also require an assumed age pattern of the excess deaths, which presumably reflect both COVID-19 directly and other pathways associated with, for example, hospital avoidance (5). I make two alternative assumptions: first, that White excess mortality is proportional over age to White all-cause mortality and, second, that White excess mortality throughout 2020 matches empirical estimates of the age patterning of COVID-19 mortality (6). This results in two alternative models for each outcome, one drawing on White COVID-19 data, and the other drawing only on pre-COVID White mortality.

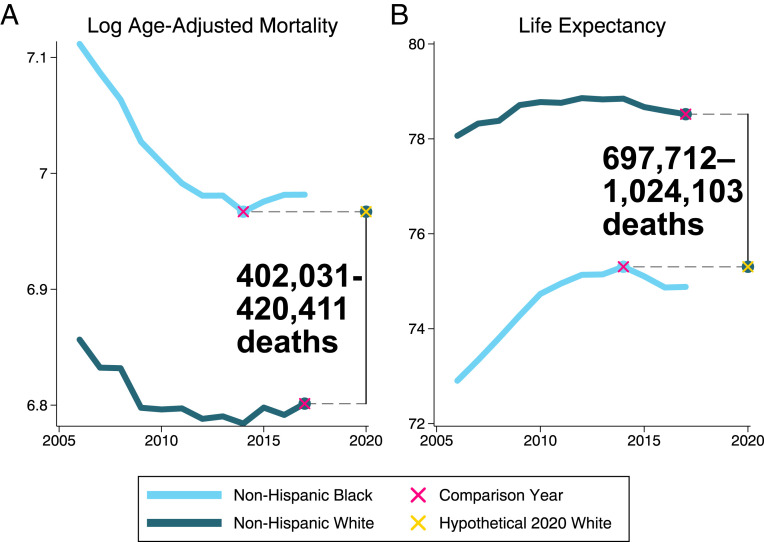

These models estimate how many deaths in 2020 would raise White mortality, or lower White lifespan, to the year of the best recorded Black rates. Fig. 2 illustrates the gap between the best mortality year for Black Americans, 2014, and the most recent year with life table estimates for White Americans, 2017, which the models translate into hypothetical death counts for the White 2020 population. The lower estimates reflect the scenario in which white excess mortality in 2020 is proportional over age to White all-cause mortality in 2017; the higher numbers reflect the scenario in which White excess mortality is proportional to White COVID-19 mortality. For hypothetical White age-adjusted mortality to equal the lowest recorded Black age-adjusted mortality, about 400,000 to 420,000 excess White deaths are needed. For White life expectancy in 2020 to fall to the level of the best-recorded Black life expectancy would require an estimated 700,000 to 1 million excess White deaths.

Fig. 2.

Hypothetical excess White mortality that would raise White mortality, or lower White life expectancy, to best-ever Black levels. (A) Logged deaths per 100,000 and (B) life expectancy for non-Hispanic Blacks and Whites, 2006 to 2017, representing all years with official US life tables for these populations. The bolded numbers represent the number of excess White deaths in 2020 needed to raise the most recent documented White mortality to the lowest-ever Black mortality, or lower the most recent documented White life expectancy to the highest-ever Black life expectancy, respectively.

The low-end estimate of about 400,000 excess White deaths is about 5.7 times the current confirmed COVID-19 deaths among Whites, representing an 18% increase in White mortality from prepandemic levels. For comparison, this estimate implies that, to reach the best-ever prepandemic Black mortality rates, the full US White population would need to experience a level of excess mortality comparable to 90% of the official COVID-19 death rate (for all racial groups) in New York City to date (7).

Discussion

These estimates make it plausible that, even in the COVID-19 pandemic, White mortality will remain lower than the lowest recorded Black mortality in the United States. If fewer than 400,000 excess White deaths occur in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic for Whites will be less consequential to overall White mortality than racial inequality is for Black mortality every year. And unless 2020 sees 700,000 to 1 million excess White deaths—a 31 to 46% mortality increase from recent years—life expectancy for Whites, even amid COVID-19, will remain higher than it has ever been for Blacks.

The legal and structural contexts that produce racial inequality have shifted dramatically since the early twentieth century, creating a more economically heterogeneous Black population (8). Yet, a century after the 1918 flu, the basic fact endures that Black disadvantage is on the scale of the worst pandemics in modern US history.

In reality, COVID-19 deaths themselves are highly disproportionately experienced by Black Americans and will almost certainly further widen the racial mortality gap (9). To date, age-adjusted confirmed COVID deaths are more than 2.5 times higher for Blacks than Whites. These deaths alone would increase the disparity between the most recent White and the best-ever Black age-adjusted mortality, shown in Fig. 2, by 27%. The results portrayed in Fig. 2 underscore that this extreme inequality in COVID deaths is layered on top of stark disparities that have existed every year.

These estimates also pose a deeper challenge. Although specific policies are highly contested, we have radically reorganized how we live to minimize the risks associated with COVID-19, with relatively high social consensus (10) and lifesaving effects (11). Yet calls to radically reorganize social institutions in order to minimize racial disparities (12–17)—such as by providing various forms of reparations, greatly expanding and universalizing social programs, defunding the police, altering school assignment mechanisms and zoning laws to combat educational and residential segregation, and increasing wages and workplace democracy—remain highly contentious (18). These results should reframe these debates away from which transformations are politically tenable to, simply, which transformations will be effective in preventing harms associated with racism. If Black disadvantage operates every year on the scale of Whites’ experience of COVID-19, then so too should the tools we deploy to fight it. Our imagination and social ambition should not be limited by how accustomed the United States is to profound racial inequality.

Materials and Methods

Historical data are from the National Center for Health Statistics (3, 19). Population denominators are from the American Community Survey, via IPUMS-USA (20), and the Census Bureau (21), and employ algorithms to allocate multiracial individuals (22). COVID-19 mortality data are from the Centers for Disease Control (6). Equations for equalizing age-adjusted mortality and life expectancy were developed by the author. Equations and their derivations, software code, and other detailed methods are available at https://osf.io/bzkcw/ (23).

Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge feedback provided by Robert Chung, Felix Elwert, Kathryn Grace, Michelle Niemann, Jenna Nobles, Matthew Plummer, Jane Sumner, and Julia Wrigley. This research was supported by the Minnesota Population Center, which is funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Award P2C HD041023), and the Fesler-Lampert Chair in Aging Studies at the University of Minnesota.

Footnotes

The author declares no competing interest.

Data Availability.

Software code, equations, and data have been deposited in Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/bzkcw/.

References

- 1.Feigenbaum J. J., Muller C., Wrigley-Field E., Regional and racial inequality in infectious disease mortality in U.S. cities, 1900-1948. Demography 56, 1371–1388 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Case A., Deaton A., Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, (Princeton University Press, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arias E., United States life tables, 2017. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 68, 1–66 (2019). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Preston S. H., Heuveline P., Guillot M., Demography: Measuring and Modeling Population Processes, (Blackwell, Oxford, United Kingdom, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lange S. J. et al., Potential indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on use of emergency departments for acute life-threatening conditions—United States, January–May 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 69, 795–800 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) , Provisional death counts for coronavirus disease 2019. (COVID-19). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid_weekly/index.htm. Accessed 29 July 2020.

- 7.City New York. Department of Health, NYC coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) data. https://github.com/nychealth/coronavirus-data. Accessed 30 July 2020.

- 8.Katz M. B., Stern M. J., Fader J. J., The new African American inequality. J. Am. Hist. 92, 75–108 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Subbaraman N., How to address the coronavirus’s outsized toll on people of colour. Nature 581, 366–367 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Igielnik R., Majority of Americans who lost a job or wages due to COVID-19 concerned states will reopen too quickly. Fact Tank (2020). https://pewrsr.ch/2Z7enZJ. Accessed 10 July 2020.

- 11.Flaxman S. et al.; Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team , Estimating the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in Europe. Nature 584, 257−261 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coates T., The case for reparations. Atlantic 313, 54–73 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Darity W. J., Kirsten Muller A., From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the Twenty-First Century, (University of North Carolina Press, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis A., Are Prisons Obsolete?, (Seven Stories, New York, NY, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franke K., Repair: Redeeming the Promise of Abolition, (Haymarket, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hannah-Jones N., What is owed. NY Times Magazine, 24 June 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/06/24/magazine/reparations-slavery.html. Accessed 30 June 2020.

- 17.Kaba M., Yes, we mean literally abolish the police. NY Times, 12 June 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/12/opinion/sunday/floyd-abolish-defund-police.html. Accessed 12 June 2020.

- 18.Williams C., Nasir N., AP-NORC poll: Most Americans oppose reparations for slavery. Associated Press, 25 October 2019. https://apnews.com/76de76e9870b45d38390cc40e25e8f03. Accessed 1 July 2020.

- 19.National Center for Health Statistics , NCHS - Death rates and life expectancy at birth. https://data.cdc.gov/NCHS/NCHS-Death-rates-and-life-expectancy-at-birth/w9j2-ggv5. Accessed 27 May 2020.

- 20.Ruggles S., IPUMS USA: Version 10.0. 10.18128/D010.V10.0. Accessed 27 May 2020. [DOI]

- 21.Census Bureau , Quick facts. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/RHI825218. Accessed 1 July 2020.

- 22.Liebler C. A., Halpern-Manners A., A practical approach to using multiple-race response data: A bridging method for public-use microdata. Demography 45, 143–155 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wrigley-Field E., U.S. Racial inequality may be as deadly as Covid-19 (replication package). Open Science Framework. https://osf.io/bzkcw/. Deposited 11 August 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Software code, equations, and data have been deposited in Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/bzkcw/.