Abstract

Objective.

Alcohol intoxication and dependence are risk factors for suicide, a leading cause of death in the United States. We examined the hours of peak and nadir in completed suicides over a 24-hour period among intoxicated, alcohol-dependent (AD) individuals. We also evaluated suicide-related factors associated with intoxication at different times of the day.

Methods.

We analyzed cross-sectional data from the 2003–2010 National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) provided by 16 U.S. states. In the primary database, the deceased individuals’ AD status was classified as “Yes” or “No or Unknown.” We restricted the analysis to AD individuals with alcohol level data available (N=3,661). The primary outcome measure was the reported time of death. Secondary outcome measures were predisposing and injury-related factors. Individuals were classified based on their blood alcohol level (BAL) as heavy drinking [BALH (≥80 mg/dL)] or non-heavy drinking [BALO (<80 mg/dL)]. The time of injury was divided into 1-hour bins, which were used to compute the incidence of suicide over 24 hours. We evaluated the association between clinical factors and BALH for each of six 4-hour time periods beginning at 00:01 hours.

Results.

The majority (73.4%) of individuals showed evidence of alcohol consumption prior to committing suicide. BALH was observed in 60.7% of all individuals. Peak incidences in suicide were identified at 21:00 and 12:00, with nadirs at 05:00 and 03:00 hours for BALH and BALO, respectively. In a multivariable analysis, between 20:01 and 00:00 hours, BALH was associated with more risk and protective factors than BALO.

Conclusion.

Identifying critical times and associated risk factors for suicidal behavior may contribute to suicide prevention efforts in intoxicated AD individuals.

Introduction

Suicide caused more than 42,000 U.S. deaths in 2014, making it the tenth leading cause of mortality1. In contrast to an overall decrease in the U.S. mortality rate, the incidence of suicide is increasing. In 2014, firearms were the most common means of committing suicide in men (55.4%) and the second most common in women (31%), after poisoning (34.1%)2. Studies have identified multiple suicide risk factors, including being male3, older2, unmarried4; and either unemployed or a blue-collar worker3,5,6; having a history of suicidal ideation or suicide attempts7,8, a chronic medical illness3,9,10, access to firearms11, a psychiatric disorder such as depression, bipolar disorder, or alcohol dependence (AD)3,7,10,12,13; and recent alcohol consumption3.

Approximately one-third of suicide victims show evidence of recent drinking4,14, and heavy drinking, in particular, is linked to an increased risk of suicide13,15–18. Heavy drinking has been defined as the consumption of ≥ 5 drinks per day on ≥ 5 days within the past 30 days19. This drinking pattern is common among individuals with AD, whose suicide rate is 60–120 times that of the general population20. Other risk factors for suicide among AD individuals include psychosocial (marital and occupational) dysfunction and comorbid chronic medical and psychiatric disorders21–23.

Another predictor of suicidal behavior is the time of day. Community-based studies evaluating circadian patterns of suicide have shown peaks and troughs across a 24-hour period. The most consistent timing of the peak has been 09:00 – 11:00 hours24–28. Other reported peaks are 12:00 – 15:0024,26, 15:00 – 18:0029 and 18:00 – 21:0028,30. In contrast, the circadian nadir for suicide has consistently been during the early morning hours (0:00 – 6:00), particularly around 2:00 – 3:0024–27,30,31. Studies have also examined sex, age, and season of the year as potential moderators of these circadian patterns. In one study, the peak incidence for males was 08:01–12:00 hours, whereas for females it was 20:01 – 24:00 hours32. Two studies showed that individuals 65 and older had a peak incidence of suicide at 8:00 – 11:00, with the peak for younger individuals being later in the day26,32. A seasonal effect has also been seen, with peaks between 9:00 – 10:00 during winter and 14:00 – 15:00 during summer27. However, there has been little research on the circadian patterns of suicides in AD individuals, including whether in this population any of the aforementioned risk factors are associated with drinking and suicidal risk at certain times of the day.

Welte and colleagues evaluated the relation between alcohol consumption and a diurnal pattern in 806 individuals who committed suicide between 1972 and 1984 in Erie County, New York. They found that the number of suicides in the subgroup with evidence of recent alcohol consumption was highest at night (N = 47), intermediate in the evening (N = 38) and lowest in the afternoon (N = 27)33. Although 60% of individuals had blood alcohol levels ≥ 0.1%, the authors did not state how many had a diagnosis of AD or how the time periods were defined. In a case series of AD individuals who attempted suicide in India (N = 30), Prasanna and colleagues identified a pattern of suicide attempts across the day34. The highest proportion of attempts occurred during the morning hours (36.7%), followed by nighttime (26.7%) and the afternoon (16.7%).

We found no published data on circadian patterns of suicide in intoxicated AD individuals, associations with suicide risk factors or information on the means of committing suicide. Thus, we examined variation in the incidence of completed suicides across the 24-hour period in AD individuals, using data from the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The availability of blood alcohol level (BAL) data in these individuals allowed us to compare the circadian pattern of suicides in intoxicated and non-intoxicated individuals. Analyzing demographic, clinical, and ballistic information enabled us to evaluate both risk and protective factors in these individuals. We sought to identify periods of increased vulnerability to suicide to focus suicide prevention efforts on the peak periods of risk for this population.

Methods

Dataset.

We obtained detailed case information from the NVDRS to investigate deaths by suicide between 2003–201035. The NVDRS dataset was originally compiled by the CDC from 18 participating U.S. states, but has now been expanded to 32 states35. Michigan and Ohio were among these 18 states and commenced with data collection in 2010. But, because state-level reporting of data commenced in 201136, we excluded the data from these two states from the analysis (n=61), leaving data from 16 states in the analysis.

NVDRS pools information on the same incident from four major sources to provide an accessible, anonymous database. The primary sources of data are death certificates and reports from coroners or medical examiners, law enforcement officials, and forensic laboratories. The information that is collected includes the circumstances related to the suicide (e.g., time of injury, presence of depression and major life stresses like relationship or financial problems)35. The University of Pennsylvania’s Institutional Review Board approved the conduct of this archival analysis project (IRB # 815690).

Subjects.

In the primary database, the deceased individuals’ AD status was classified as “Yes” or “No or Unknown.” We extracted data only for individuals for whom this variable was coded as “present” and for whom blood alcohol data was available (N = 3,722, which was 10.5% of the total sample of 35,332). After deleting the 61 observations from Ohio and Michigan, our final analytic sample comprised 3,661 individuals.

Variables.

a. Demographic variables including age; sex; race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, black/African-American, Hispanic/Latino, Asian, and other); education; and marital, veteran, and homelessness status were extracted from case reports; b. Time of fatal injury was the reported time when the act of suicide occurred. It was rounded to the nearest integer such that any time within the first 59 minutes of a particular hour was categorized as occurring within that hour.36 In addition, we created six 4-hour time bins from the hourly information25,32. The categories were 00:01–04:00, 04:01–08:00, 08:01–12:00, 12:01–16:00, 16:01–20:00, and 20:01–00:0032; c. Blood alcohol level (BAL) obtained from their post-mortem examination records was recorded in mg/dL. The threshold for heavy drinking was set at BAL ≥ 80 mg/dL, i.e., the legal limit for driving in most states and used by the CDC in reporting NVDRS data and in previous studies37–40. Individuals were classified into 1 of 3 drinker categories based on their blood alcohol levels: 1) None: BALneg (0 mg/dL); 2) Moderate: BALmod (>0 and <80 mg/dL), and 3) Heavy: BALH (≥ 80 mg/dL)37–39; d. Drug screen findings were obtained from the post-mortem reports; e. Likely predisposing factors included prior treatment for a mental health problem, mental health diagnoses, current depressed mood, previous suicide attempts, physical health problems, job problems, recent legal problems, and financial problems; f. Suicide injury-related factors included the season of the year and means used. The seasons of the year were Winter (Dec-Feb), Spring (Mar-May), Summer (Jun-Aug), and Fall (Sep-Nov). The means of suicide included a firearm, poisoning, hanging, strangulation, suffocation, and other. Firearm-related variables included the firearm type; caliber; whether the firearm was stolen, stored locked, or stored loaded; and the owner of the gun.

Data Analysis.

Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the frequency of suicides for each hour of injury between BALneg and BALmod groups. Because BALneg and BALmod groups did not differ at any time point at a Bonferroni-adjusted significance level (p <0.002), the two groups were combined into the BALO group, to which BALH was compared in all subsequent analyses.

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the overall sample and stratified into BALH and BAHO subgroups. Fisher’s exact tests, extended Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel statistics, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were employed to compare the subgroups on descriptive variables. Qualitative differences in the temporal patterns of suicides were assessed on an hourly basis using plots for the total sample and for the subgroups, with differences assessed with Fisher’s exact tests. Odds ratios were used to estimate the probability of suicide occurring at each hour for individuals classified as BALH compared to BALO.

We also used socio-demographic variables, predisposing factors, and suicide injury-related factors (the reference group being BALO) to evaluate risk and protective factors for alcohol intoxication (BALH) for the six 4-hour bins of time of injury. Because bivariate analyses revealed multiple associations between characteristics of interest and BALH for the six individual time bins, we used six separate multivariable logistic regression models to evaluate the correlates of BALH for the time bins, using the factors identified as significant (p<0.05) as predictors in the bivariate analyses. We used modified stepwise regression analyses to determine the final model and the likelihood ratio test and Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to select the best model for each time bin. Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel statistics and ANOVAs were used to evaluate differences among the means across the categories of alcohol consumption or 4-hour circadian bin during which the suicide occurred. Data analysis was conducted using SAS© 9.4 software41.

Results

As shown in Table 1, the mean age of the sample was 43 years (SD = 13.3) and it was primarily white (n=3391, 93%) and male (n=3086, 84%). Twenty-five percent (n=929) of the sample had previously attempted suicide. The average BAL at the time of death for the BALH group was 208.7 mg/dL (SD=85.6). The majority (60.7%) of suicide victims were in the BALH category. More than half of the suicides (n=2136, 58%) were committed with a firearm. Among individuals tested for drug use following the suicide (n=2027, 55.4%), 76% tested positive (n=1537) for at least one of the following drugs: amphetamines (n=90, 4%), cocaine (n=278, 11%), marijuana (n=188, 10%), opiates (n=337, 13%), or other drugs (n=975, 44%). Twenty-two percent (n=485) of individuals screened positive for antidepressant use during post-mortem examination. Notably, the BALO group had a significantly higher proportion of individuals with a history of mental health treatment (53% vs. 40%, p<0.0001), a previous suicide attempt (28% vs. 24%, p=.02), and a positive toxicological test at suicide (84% vs. 70%, p<0.0001).

Table 1.

Demographic, predisposing, and lethal self-injury related characteristics of the sample.

| n | Overall (n=3661) | BALH (n=2222) | BALO (n = 1439) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Age mean (S.D.) | 3661 | 42.8 (13.3) | 42.3 (12.8) | 43.5 (14.1) | 0.01 |

| Male | 3661 | 3086 (84.3) | 1893 (85.2) | 1193 (82.9) | 0.07 |

| Race | 3661 | 0.005 | |||

| White | 3391 (92.6) | 2072 (93.3) | 1319 (91.7) | ||

| Black | 142 (3.9) | 68 (3.1) | 74 (5.1) | ||

| Othera | 128 (3.5) | 82 (3.7) | 46 (3.2) | ||

| Hispanic | 3654 | 226 (6.2) | 135 (6.1) | 91 (6.3) | 0.78 |

| Marital Status | 3643 | 0.52 | |||

| Married | 1432 (39.1) | 885 (40.0) | 547 (38.3) | ||

| Never married | 1130 (31.0) | 672 (30.4) | 458 (32.0) | ||

| Otherb | 1081 (29.7) | 656 (29.6) | 425 (29.7) | ||

| Education | 1793e | 0.89 | |||

| Less than HS | 397 (22.1) | 238 (21.3) | 159 (23.6) | ||

| HS graduate | 797 (44.5) | 514 (46.0) | 283 (41.9) | ||

| More than HS | 599 (33.4) | 366 (32.7) | 233 (34.5) | ||

| Veteran | 3501 | 687 (19.6) | 407 (19.1) | 280 (20.5) | 0.34 |

| Homeless | 3557 | 48 (1.4) | 29 (1.4) | 19 (1.4) | 1.00 |

| Likely predisposing factors | |||||

| Previous treatment for mental health problem | 3661 | 1643 (44.9) | 879 (40.0) | 764 (53.1) | <0.0001 |

| Type of First Mental Diagnoses | 1718e | 0.005 | |||

| Depression/dysthymia | 1396 (81.3) | 613 (79.1) | 783 (83.0) | ||

| Bipolar disorder | 172 (10.0) | 95 (12.3) | 77 (8.2) | ||

| Schizophrenia | 36 (2.1) | 24 (3.1) | 12 (1.3) | ||

| Anxiety disorder | 43 (2.5) | 17 (2.2) | 26 (2.8) | ||

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 23 (1.3) | 8 (1.0) | 15 (1.6) | ||

| ADD or hyperactivity disorder | 13 (0.8) | 4 (0.5) | 9 (1.0) | ||

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 4 (0.2) | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| Otherc | 31 (1.8) | 11 (1.4) | 20 (2.1) | ||

| Current depressed mood | 3661 | 1817 (49.6) | 723 (50.2) | 1094 (49.2) | 0.55 |

| Previous suicide attempt | 3661 | 929 (25.4) | 534 (24.0) | 395 (27.5) | 0.02 |

| Physical health problem | 3661 | 552 (15.1) | 313 (14.1) | 239 (16.6) | 0.04 |

| Job problem | 3661 | 710 (19.4) | 447 (20.1) | 263 (18.3) | 0.17 |

| Recent criminal legal problem | 3661 | 580 (15.8) | 330 (14.9) | 250 (17.4) | 0.05 |

| Financial problem | 3661 | 588 (16.1) | 357 (16.1) | 231 (16.1) | 1.00 |

| Suicide injury-related factors | |||||

| BAL (mg/dL) mean(%) | 3661 | 131.4 (117.7) | 208.7 (85.6) | 12.1 (21.6) | N/A |

| Season of the year | 3661 | 0.88 | |||

| Summer (Jun-Aug) | 1026 (28.0) | 636 (28.6) | 390 (27.1) | ||

| Spring (Mar-May) | 906 (24.8) | 540 (24.3) | 366 (25.4) | ||

| Fall (Sep-Nov) | 868 (23.7) | 525 (23.6) | 343 (23.8) | ||

| Winter (Dec-Feb) | 861 (23.5) | 521 (23.5) | 340 (23.6) | ||

| Weapon used | 3656 | <0.0001 | |||

| Firearm | 2136 (58.4) | 1409 (63.5) | 727 (50.6) | ||

| Hanging, strangulation, suffocation | 771 (21.1) | 464 (20.9) | 307 (21.4) | ||

| Poisoning | 481 (13.2) | 208 (9.4) | 273 (19.0) | ||

| Otherd | 268 (7.3) | 139 (6.3) | 129 (9.0) | ||

| Positive for any drug other than alcohol* | 2027e | 1537 (75.8) | 845 (70.0) | 692 (84.4) | <0.0001 |

| Opiates | 2536 | 337 (13.3) | 153 (10.0) | 184 (18.2) | <0.0001 |

| Cocaine | 2554 | 278 (10.9) | 168 (10.9) | 110 (10.8) | 0.95 |

| Marijuana | 1899 | 188 (9.9) | 121 (10.0) | 67 (9.7) | 0.81 |

| Amphetamines | 2424 | 90 (3.7) | 43 (2.9) | 47 (5.0) | 0.01 |

| Other drugs | 2210 | 975 (44.1) | 512 (39.4) | 463 (50.9) | <0.0001 |

| Antidepressants | 2221 | 485 (21.8) | 249 (18.4) | 236 (27.3) | <0.0001 |

Includes, but is not limited to: American Indian, Asian/Pacific Islander.

Includes widowed, divorced, married but separated, and single (not otherwise specified).

Specific data for this category was not available.

Includes, but is not limited to: non-powder gun, sharp instrument, blunt instrument, fall, explosive, drowning, fire or burns, motor vehicle (e.g., buses, motorcycles), other transport vehicle (e.g., trains, planes, boats).

Greater than 10% of responses are missing, therefore excluded from univariable and multivariable analyses.

HS: High School, BAL: Blood Alcohol Level

Percentage displayed is the percentage of individuals tested who had a positive result.

Bold indicates significance at α=0.05.

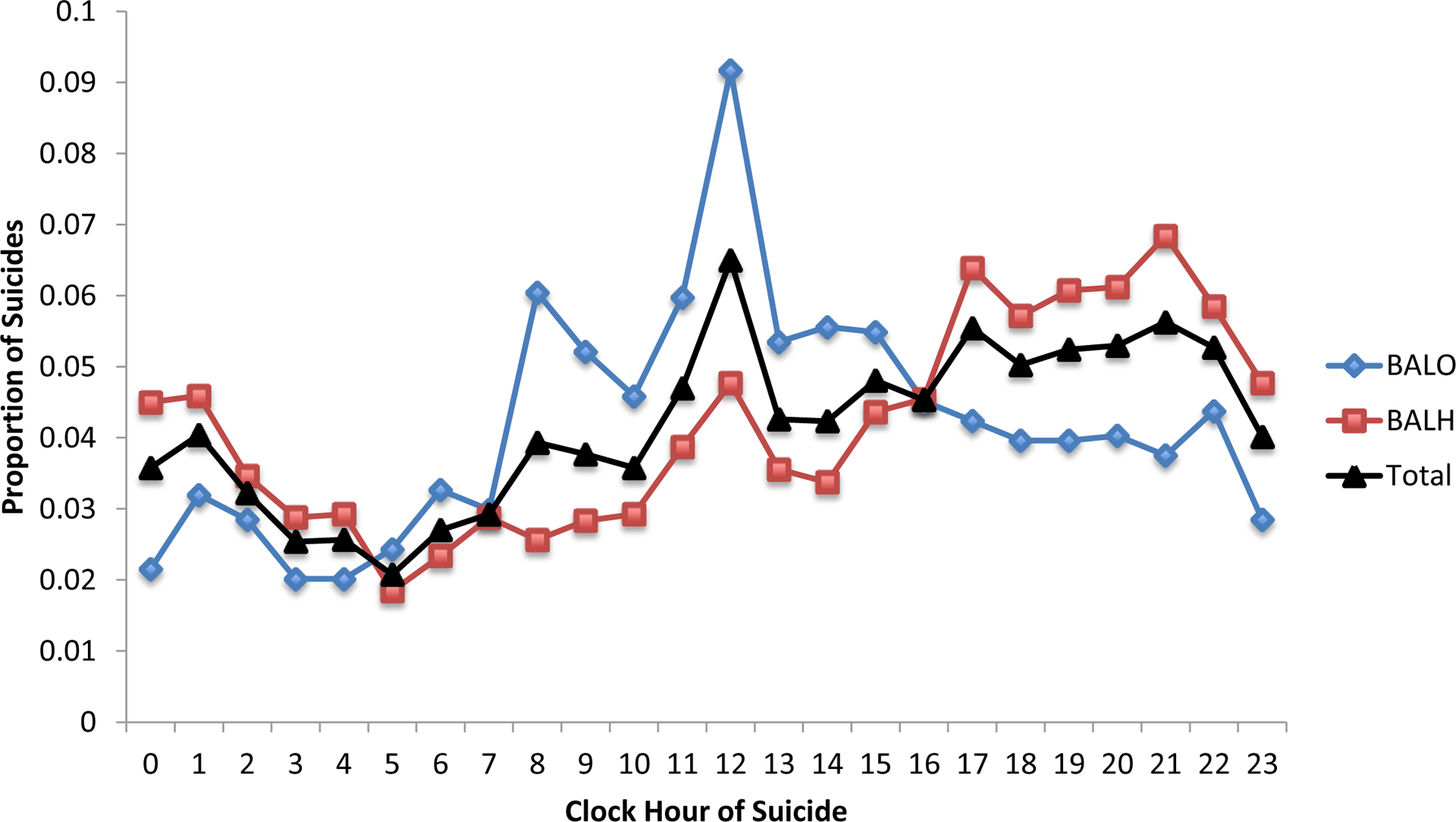

As shown in Figure 1, overall, the highest proportion of suicides occurred in the latter half of the day (i.e., between 12:00 and 23:00) with the primary peak at 12:00 (7% of all suicides) and secondary peaks at 17:00 (6%) and 21:00 (6%). The lowest proportion of suicides occurred in the early morning at 05:00 (2%).

Figure 1. Proportion of suicides that occur per hour by BAL at death.

BAL: Blood Alcohol Level (in mg/dL); BAL O: combined subgroups BALneg (0 mg/dL) and moderate BALmod, i.e., >0 and <80 mg/dL (N = 1439); BAL H: intoxicated alcohol-dependent individuals, i.e., ≥ 80 mg/dL (N = 2222); Total: total sample of alcohol-dependent individuals (N = 3661).

When stratified by BAL, different patterns emerged. The BALH group had higher rates of suicide from 17:00 to 01:00, with a peak at 21:00. In contrast, the BALO group had substantially higher rates of suicide than the BALH group from 08:00 to 15:00, with a peak at around 12:00. The groups had similar rates of suicide between 02:00 and 07:00, with the nadir of suicide for BALH and BALO at 05:00 and 03:00, respectively.

Using a Bonferroni-adjusted significance level of 0.002, there were 6 time points at which the BALH group (n=2222) differed significantly from the BALO group (n=1439). When suicides occurred at 21:00 or 00:00, the individual was more likely to be in the BALH category. In contrast, suicides at 08:00, 09:00, 12:00, or 14:00 were more likely to be in the BALO category. Predictors of BALH in individual bivariate analyses within each 4-hr time bin of the day are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Predictors of BALH within each 4-hr time bin of the day in individual bivariate analyses

| (00:01 – 04:00) | (4:01 – 08:00) | (8:01 – 12:00) | (12:01 – 16:00) | (16:01 – 20:00) | (20:01 – 00:00) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=495) | OR (95% CI) | (N=375) | OR (95% CI) | (N=660) | OR (95% CI) | (N=657) | OR (95% CI) | (N=755) | OR (95% CI) | (N=719) | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Demographics | |||||||||||||

| Age mean (S.D.) | 37.3 (13.2) | 0.99 (0.98 – 1.01) | 41.5 (13.8) | 0.97 (0.95 – 0.98) | 45.4 (12.9) | 0.99 (0.98 – 1.01) | 44.8 (12.8) | 1.01 (1.00 – 1.02) | 44.4 (13.1) | 1.02 (1.00 – 1.03) | 41.4 (12.9) | 1.00 (0.98 – 1.01) | <0.0001 |

| Male % (N) | 86.1% (426) | 0.91 (0.51 – 1.60) | 83.7% (314) | 1.17 (0.68 – 2.03) | 84.2% (556) | 0.97 (0.63 – 1.47) | 80.4% (528) | 1.22 (0.83 – 1.80) | 84.9% (641) | 1.39 (0.92 – 2.10) | 86.4% (6210 | 1.13 (0.72 – 1.80) | 0.7277 |

| Whitea % (N) | 89.9% (445) | 0.93 (0.49, 1.79) | 88.3% (331) | 0.62 (0.32 – 1.19) | 94.6% (624) | 1.38 (0.69 – 2.75) | 92.9% (610) | 1.17 (0.65 – 2.13) | 93.5% (706) | 2.41 (1.35 – 4.32) | 93.9% (675) | 1.91 (1.03 – 3.55) | 0.0012 |

| Hispanic % (N) | 6.9% (34) | 0.99 (0.46 – 2.12) | 10.2% (38) | 0.98 (0.50 – 1.93) | 7.6% (50) | 1.51 (0.85 – 2.70) | 4.4% (29) | 0.50 (0.23 – 1.09) | 5.2% (39) | 0.92 (0.46 – 1.82) | 5.0% (36) | 1.08 (0.51 – 2.29) | 0.0023 |

| Marital Status | 0.3097 | ||||||||||||

| Married % (N) | 33.4% (165) | REF | 37.8% (141) | REF | 38.5% (254) | REF | 40.4% (264) | REF | 42.9% (321) | REF | 40.1% (287) | REF | |

| Never married % (N) | 43.7% (216) | 1.25 (0.80 – 1.96) | 35.1% (131) | 1.87 (1.15 – 3.03) | 26.3% (173) | 1.15 (0.78 – 1.70) | 27.1% (177) | 0.74 (0.51 – 1.09) | 27.0% (202) | 0.59 (0.40 – 0.86) | 32.3% (231) | 0.52 (0.36 – 0.77) | |

| Otherb % (N) | 22.9% (113) | 1.07 (0.64 – 1.80) | 27.1% (101) | 1.20 (0.72 – 2.00) | 35.2% (232) | 1.13 (0.79 – 1.61) | 32.5% (212) | 0.99 (0.69 – 1.42) | 30.1% (225) | 0.89 (0.61 – 1.30) | 27.7% (198) | 0.84 (0.56 – 1.28) | |

| Veteran % (N) | 13.5% (65) | 0.91 (0.51 – 1.60) | 19.4% (70) | 0.66 (0.39 – 1.11) | 19.6% (125) | 1.08 (0.73 – 1.60) | 19.7% (123) | 1.01 (0.68 – 1.50) | 21.0% (150) | 1.19 (0.80 – 1.78) | 22.6% (154) | 0.66 (0.45 – 0.97) | 0.0004 |

| Homeless % (N) | 1.2% (6) | 0.82 (0.15, 4.52) | 1.9% (7) | 2.01 (0.39 – 10.51) | 2.2% (14) | 1.16 (0.40 – 3.34) | 1.1% (7) | 0.73 (0.16 – 3.29) | 1.0% (7) | 1.17 (0.23 – 6.06) | 1.0% (7) | 1.06 (0.20 – 5.51) | 0.1771 |

| Likely predisposing factors | |||||||||||||

| Previous treatment for mental health problem % (N) | 39.6% (196) | 0.46 (0.31 – 0.68) | 41.9% (157) | 0.63 (0.41 – 0.95) | 41.2% (318) | 0.76 (0.56 – 1.03) | 50.7% (333) | 0.52 (0.39 – 0.72) | 43.6% (329) | 0.67 (0.49 – 0.91) | 43.1% (310) | 0.54 (0.39 – 0.74) | 0.3785 |

| Current depressed mood % (N) | 46.9% (232) | 0.79 (0.54 – 1.16) | 46.9% (176) | 0.62 (0.41 – 0.93) | 55.5% (366) | 1.46 (1.07 – 1.99) | 51.5% (338) | 1.06 (0.78 – 1.43) | 48.3% (365) | 0.91 (0.67 – 1.23) | 47.3% (340) | 1.14 (0.82 – 1.57) | 0.6822 |

| Previous suicide attempts % (N) | 25.3% (125) | 0.73 (0.47 – 1.12) | 23.7% (89) | 0.97 (0.60 – 1.56) | 26.1% (172) | 1.14 (0.81 – 1.62) | 27.7% (182) | 0.79 (0.56 – 1.11) | 23.1% (174) | 0.76 (0.53 – 1.09) | 26.0% (187) | 0.76 (0.53 – 1.09) | 0.9793 |

| Physical health problem % (N) | 12.1% (60) | 0.74 (0.42 – 1.31) | 14.9% (56) | 0.54 (0.31 – 0.97) | 15.3% (101) | 0.96 (0.63 – 1.47) | 16.9% (111) | 0.88 (0.58 – 1.32) | 16.2% (122) | 1.07 (0.70 – 1.63) | 14.2% (102) | 0.73 (0.47 – 1.13) | 0.2804 |

| Job problem % (N) | 19.8% (98) | 1.04 (0.64 – 1.70) | 16.8% (63) | 0.79 (0.46 – 1.35) | 22.0% (145) | 1.10 (0.76 – 1.60) | 19.9% (131) | 1.07 (0.73 – 1.57) | 18.9% (143) | 1.23 (0.82 – 1.84) | 18.1% (130) | 1.83 (1.15 – 2.91) | 0.5155 |

| Recent criminal legal problem % (N) | 13.5% (67) | 1.26 (0.70 – 2.26) | 14.1% (53) | 0.73 (0.41 – 1.31) | 21.2% (140) | 0.93 (0.64 – 1.36) | 16.4% (108) | 0.65 (0.43 – 0.99) | 14.0% (106) | 0.76 (0.50 – 1.17) | 14.7% (106) | 1.26 (0.78 – 2.01) | 0.6282 |

| Financial problem % (N) | 17.8% (88) | 1.13 (0.67 – 1.89) | 14.4 (54) | 0.59 (0.33 – 1.05) | 17.3% (114) | 1.41 (0.94 – 2.12) | 16.4% (108) | 0.85 (0.57 – 1.29) | 15.8% (119) | 0.89 (0.59 – 1.35) | 14.6% (105) | 1.24 (0.77 – 1.98) | 0.2308 |

| Suicide injury related factors | |||||||||||||

| Season of the year | 0.1120 | ||||||||||||

| Winter (Dec-Feb) % (N) | 26.3% (130) | 0.76 (0.43 – 1.32) | 21.9% (82) | 1.05 (0.58 – 1.91) | 25.9% (171) | 0.83 (0.53 – 1.31) | 21.8% (143) | 1.12 (0.72 – 1.72) | 24.2% (183) | 1.12 (0.72 – 1.72) | 21.1% (152) | 0.88 (0.55 – 1.41) | |

| Spring (Mar-May) % (N) | 23.4% (116) | REF | 25.6% (96) | REF | 20.3% (134) | REF | 29.8% (196) | REF | 24.4% (184) | REF | 25.0% (180) | REF | |

| Summer (Jun-Aug) % (N) | 27.7% (137) | 0.76 (0.44 – 1.32) | 25.1% (94) | 0.75 (0.42 – 1.32) | 31.1% (205) | 1.23 (0.80 – 1.91) | 26.6% (175) | 1.17 (0.78 – 1.76) | 27.4% (207) | 1.17 (0.78 – 1.76) | 28.9% (208) | 1.35 (0.86 – 2.14) | |

| Fall (Sep-Nov) % (N) | 22.6% (112) | 0.91 (0.51 – 1.64) | 27.5% (103) | 1.00 (0.57 – 1.75) | 22.7% (150) | 1.08 (0.67 – 1.72) | 21.8% (143) | 1.44 (0.93 – 2.21) | 24.0% (181) | 1.44 (0.93 – 2.21) | 24.9% (179) | 0.75 (0.48 – 1.17) | |

| Weapon used | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||

| Firearm % (N) | 54.9% (270) | 1.17 (0.56 – 2.48) | 50.7% (190) | 1.81 (0.84 – 3.87) | 53.6% (353) | 1.83 (0.92 – 3.61) | 57.5% (378) | 1.62 (0.92 – 2.85) | 65.0% (491) | 1.62 (0.92 – 2.85) | 63.2% (454) | 2.50 (1.32 – 4.71) | |

| Hanging, strangulation, suffocation % (N) | 25.8% (127) | 0.89 (0.40 – 1.96) | 26.9% (101) | 2.32 (1.03 – 5.23) | 22.0% (145) | 1.99 (0.96 – 4.12) | 19.3% (127) | 1.26 (0.67 – 2.37) | 16.2% (122) | 1.26 (0.67 – 2.37) | 20.8% (149) | 1.46 (0.74 – 2.90) | |

| Poisoning % (N) | 11.2% (55) | 0.37 (0.15 – 0.88) | 13.9% (52) | 1.84 (0.76 – 4.50) | 18.4% (121) | 0.99 (0.47 – 2.09) | 14.6% (96) | 0.54 (0.27 – 1.06) | 11.4% (86) | 0.54 (0.27 – 1.06) | 9.9% (71) | 0.78 (0.37 – 1.67) | |

| Otherc % (N) | 8.1% (40) | REF | 8.5% (32) | REF | 6.1% (40) | REF | 8.5% (56) | REF | 7.4% (56) | REF | 6.1% (44) | REF | |

OR: odds ratio with BALO as the reference group; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; REF: reference group.

Compared to a combined race category, which includes, but is not limited to: black, American Indian, Asian/Pacific Islander.

Includes widowed, divorced, married but separated, and single (not otherwise specified).

Includes, but is not limited to: non-powder gun, sharp instrument, blunt instrument, fall, explosive, drowning, fire or burns, motor vehicle (e.g., buses, motorcycles), other transport vehicle (e.g., trains, planes, boats).

P-value corresponds to differences between time bin groups.

Bold indicates a significant bivariate association at α=0.05.

Predictors of BALH within each 4-hr time bin of the day in multivariable analyses

a) (00:01–04:00). Prior mental health treatment and suicide by poisoning were associated with decreased odds of having a BALH at the time of death (Table 3); b) (04:01–08:00). Younger age and depressed mood around the time of suicide were associated with decreased odds of having a BALH at the time of death; c) (08:01–12:00). Depressed mood around the time of suicide was associated with an increased probability of having a BALH at the time of death; d) (12:01–16:00). A recent criminal legal problem was associated with decreased odds of having a BALH at the time of death; e) (16:01–20:00). Being white was associated with nearly 2.5 times the odds of having a BALH at the time of death compared to non-white individuals, whereas previous treatment for a mental health problem was associated with a decreased odds of having a BALH at the time of death; f) (20:01–0:00). Individuals who were never married, veterans, and those with previous mental health treatment had a decreased probability of having a BALH at the time of death. Having a problem at work and using a firearm to commit suicide were associated with an increased probability of having BALH at the time of death.

Table 3.

Predictors of BALH within each 4-hr time bin of the day in multivariable analyses

| Variable | aOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| (00:01–04:00) | Previous treatment for mental health problem** | 0.51 (0.34 – 0.77) |

| Weapon used* | ||

| Firearm | 1.05 (0.49 – 2.25) | |

| Poisoning | 0.39 (0.16 – 0.93) | |

| Hanging, strangulation, suffocation | 0.77 (0.34 – 1.71) | |

| Othera | REF | |

| (04:01–08:00) | Age*** | 0.97 (0.95–0.98) |

| Current depressed mood* | 0.59 (0.39–0.90) | |

| (08:01–12:00) | Current depressed mood* | 1.46 (1.07–1.99) |

| (12:01–16:00) | Recent criminal legal problem* | 0.65 (0.43–0.99) |

| (16:01–20:00) | White** | 2.49 (1.38–4.47) |

| Previous treatment for mental health problem** | 0.66 (0.48–0.90) | |

| (20:01–00:00) | Marital status** | |

| Married | REF | |

| Never married | 0.56 (0.37–0.83) | |

| Otherb | 0.94 (0.60–1.47) | |

| Veteran** | 0.52 (0.35–0.79) | |

| Previous treatment for mental health problem* | 0.63 (0.44–0.90) | |

| Job problem* | 1.78 (1.08–2.93) | |

| Weapon used*** | ||

| Firearm | 2.47 (1.25–4.91) | |

| Poisoning | 0.92 (0.41–2.06) | |

| Hanging, strangulation, suffocation | 1.41 (0.68–2.95) | |

| Othera | REF |

aOR = adjusted Odds Ratio; p values correspond to Type III analysis of effects;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001;

Includes, but is not limited to: non-powder gun, sharp instrument, blunt instrument, fall, explosive, drowning, fire or burns, motor vehicle (e.g., buses, motorcycles), other transport vehicle (e.g., trains, planes, boats);

Includes widowed, divorced, married but separated, and single (not otherwise specified).

Weapons, alcohol consumption and circadian pattern.

The most common class of weapons used to commit suicide was handguns, followed by shotguns and rifles. However, no differences were observed for type, caliber or other weapon-related variables when compared across alcohol consumption categories. When suicides were examined across circadian bins, gun ownership status was a significant predictor (p=0.04), with the victim being more likely to be the owner of the gun, Table 4.

Table 4.

Weapon-related details and circadian bins

| Circadian bin | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (00:01–04:00) (N=270) | (04:01–08:00) (N=190) | (08:01–12:00) (N=353) | (12:01–16:00) (N=378) | (16:01–20:00) (N=491) | (20:01–00:00) (N=454) | p | |

| Firearm type | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | .20 |

| Handgun | 176 (65.2) | 128 (67.4) | 235 (66.6) | 267 (70.6) | 342 (69.7) | 324 (71.4) | |

| Shotgun | 38 (14.1) | 26 (13.7) | 53 (15.0) | 64 (16.9) | 74 (15.1) | 67 (14.8) | |

| Rifle | 49 (18.1) | 32 (16.8) | 59 (16.7) | 43 (11.4) | 67 (13.6) | 55 (12.1) | |

| Other | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (0.8) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Combination | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Not reported | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Unknown | 6 (2.2) | 2 (1.1) | 3 (0.8) | 3 (0.8) | 7 (1.4) | 8 (1.8) | |

| Firearm caliber | N=187 | N=143 | N=266 | N=273 | N=345 | N=336 | .26 |

| Mean (SD) (in) | .33 (.08) | .34 (.08) | .33 (.08) | .34 (.07) | .34 (.07) | .34 (.07) | |

| Median (IQR) (in) | .35 (.16) | .36 (.11) | .36 (.16) | .36 (.09) | .36 (.10) | .36 (.08) | |

| Range (in) | .22–.50 | .22–.54 | .22–.50 | .22–.46 | .17–.45 | .22–.50 | |

| Stolen firearm | .54 | ||||||

| No | 36 (13.3) | 35 (18.4) | 48 (13.6) | 44 (11.6) | 58 (11.8) | 55 (12.1) | |

| Yes | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Not applicable | 7 (2.6) | 2 (1.1) | 6 (1.7) | 10 (2.6) | 10 (2.0) | 14 (3.1) | |

| Unknown | 226 (83.7) | 152 (80.0) | 297 (84.1) | 322 (85.2) | 420 (85.6) | 385 (84.8) | |

| Stored gun locked | .66 | ||||||

| Not locked | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.1) | 5 (1.4) | 1 (0.3) | 4 (0.8) | 4 (0.9) | |

| Locked | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.6) | 3 (0.8) | 3 (0.6) | 3 (0.7) | |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Not applicable | 64 (23.7) | 51 (26.8) | 74 (21.0) | 89 (23.5) | 113 (23.0) | 107 (23.6) | |

| Unknown | 204 (75.5) | 137 (72.1) | 272 (77.1) | 285 (75.4) | 371 (75.5) | 339 (74.6) | |

| Stored gun loaded | .28 | ||||||

| Unloaded | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.8) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.9) | |

| Loaded | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | |

| Not applicable | 63 (23.3) | 51 (26.8) | 72 (20.4) | 89 (23.5) | 113 (23.0) | 107 (23.6) | |

| Unknown | 207 (76.6) | 138 (72.6) | 276 (78.2) | 287 (75.9) | 377 (76.7) | 341 (75.1) | |

| Gun owner | .04 | ||||||

| Shooter | 30 (11.1) | 15 (7.9) | 39 (11.0) | 29 (7.7) | 45 (9.2) | 36 (7.9) | |

| Parent | 5 (1.9) | 1 (0.5) | 5 (1.4) | 2 (0.5) | 5 (1.0) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Other family member | 2 (0.7) | 2 (1.1) | 9 (2.5) | 5 (1.3) | 2 (0.4) | 9 (2.0) | |

| Friend/acquaintance | 4 (1.5) | 6 (3.2) | 6 (1.7) | 6 (1.6) | 4 (0.8) | 11 (2.4) | |

| Stranger | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 7 (1.4) | 3 (0.7) | |

| Unknown | 228 (84.5) | 166 (87.4) | 293 (83.0) | 335 (88.6) | 427 (87.0) | 394 (86.8) | |

Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel statistics used for categorical variables (row mean scores differ for the general association statistic for the circadian bin); ANOVAs used for the continuous variable (caliber)

Discussion

Despite evidence of a circadian pattern of suicides in the general population and both alcohol use and dependence being established risk factors for suicide, little is known about the circadian pattern of suicides in AD individuals. Here, we found that, overall, suicides peaked at 12:00, with a nadir at 05:00. A majority of individuals who committed suicide had a high BAL (≥ 80 mg/dL) and a later peak time of completed suicide (21:00) than un-intoxicated individuals (12:00). Intoxicated individuals who committed suicide later in the evening had more risk and protective factors than intoxicated individuals who committed suicide at other times. Finally, intoxicated individuals who committed suicide in the afternoon or evening were more likely to do so with a gun.

We found that suicide was more likely to occur at midday in our AD sample, which is in line with prior community-based studies25–27. Suicides in intoxicated individuals peaked in the evening and were more likely to involve a gun, also consistent with prior findings33 and with the notion that people are more likely to drink alcohol later in the day, which predisposes them to impulsive and suicidal behavior33. Our findings differ from those of Prasanna and colleagues, who found that suicide attempts in intoxicated AD individuals occurred most often in the morning (36.7%) and at night-time (26.7%)34. The disparity between their study results and ours may be due to their small sample size (N = 30). Alternatively, lethal suicidal intent may be associated with different peak times than non-lethal intent.

Multiple factors influence the later time for the peak incidence of suicides in individuals who are intoxicated. Animal studies have shown a greater sensitivity to the depressant effects of alcohol around the usual sleep time42,43, which may lead to more unpredictable and impulsive behavior33,44,45. Heavy drinking may also be associated with mood disturbance, a sense of hopelessness15,44,46 and problematic interactions with family or friends, especially in the evening, when people usually socialize. Recurrent drinking, stress, and maladaptive behavior could lead to a repetitive cycle from which suicide is viewed as an escape15,47.

Psychiatric disorders commonly co-occur with AD23 and treating both disorders can decrease suicide risk in AD individuals44. The most common psychiatric disorders in individuals in this study were depressive disorder and dysthymic disorder. About half of the AD individuals had a depressed mood prior to suicide, a powerful risk factor for suicide in AD individuals with depressive disorder and heavy drinking44. Depressed mood may fluctuate across the day in distressed individuals, with the greatest intensity in the morning, and a gradual improvement over the course of the day48. Thus, an association between depressed mood and BALH in the 8:00–12:00 bin is not surprising.

However, the inverse relationship between depressed mood and BALH in the 04:01–8:00 time bin may have been due to the interaction between sleep-related problems and a circadian variation in mood. That is, because interrupted sleep and early morning awakening are common symptoms of alcohol use and depressive disorder49,50, individuals could have awakened depressed and, lacking access to alcohol, they could not use it for self-medication.

Mental health treatment is another area where some unique findings were obtained on post-hoc analysis. Only 22% of the total sample and 13% of those with a history of psychiatric disorders screened positive for antidepressant medication on toxicological testing. This may reflect nonadherence (with psychiatric care, psychotropic medications, or both) or a poor treatment response from the medication. The Nordic Cochrane Center conducted a recent meta-analytic review of data from 70 clinical trials of antidepressant medications51. Their results demonstrated the lack of an association between suicidal behavior and antidepressant medications in adults. It is possible that suicidal behavior emerging during treatment may be secondary to the worsening of mood and anxiety symptoms because of a lack of a therapeutic response from an antidepressant medication rather than a direct side effect from it, as shown before52. Thus, improving access to psychiatric treatment and monitoring treatment compliance and effectiveness53 could reduce the risk of suicide in this population.

The BALO subgroup had a significantly higher proportion of individuals with prior mental health treatment (53% vs. 40%) and individuals with positive toxicology screens for antidepressants were more likely to have a BALO within the hours of 20:01 and 08:00. Thus, individuals receiving psychiatric treatment may have drunk less than those who needed treatment but were not receiving it. However, their conduct of suicide raises questions about other possible risk factors such as problematic social supports, comorbid medical disorders21–23 and possibly antidepressant medications themselves54–56.

Our finding that firearms were the most common means of suicide is highly consistent with both prior literature and recent CDC findings demonstrating this association2. The association between firearms and alcohol intoxication in the evening may reflect impulsivity augmented by intoxication, which in the absence of lethal means (e.g., firearms) may not result in death. Other risk factors that were associated with alcohol intoxication at the time of death included being white and having job-related problems, established risk factors for both heavy drinking and suicidal behavior4,5,57. The association between current job problems and alcohol intoxication seen in the late evening hours may be a particularly relevant set of co-occurring risk factors, as seen previously39.

Limitations of the current investigation include the fact that the time of death was based on the time of injury, which is not always the same. The selection of an enriched sample of AD individuals with available BAL level data may have introduced a selection bias. These AD individuals may not be representative of all AD individuals who completed suicide. In addition, some of them may have been over-classified or under-classified as being AD individuals. It is also possible that the BAL at the time of death may not reflect the individuals’ habitual drinking patterns. The current employment status of most of the individuals was unavailable. Therefore, we used job-related problems at the time of death as an indicator that an individual was occupied and as a measure of work-associated problems. However, we do not know how correlated current employment status and job-related problems were. Intoxicated individuals had relatively fewer health problems and past suicide attempts but more job-related problems. Although comorbid mood and anxiety disorders are prevalent in AD23, fewer medical and psychiatric problems identified in intoxicated individuals may reflect an ascertainment bias, or the lack of an adequate clinical history. The toxicological evidence of antidepressant medications may have been an underestimate due to partial or complete non-adherence with these medications58,59. In addition, the duration of antidepressant medication use is unclear for individuals who tested positive for them. Finally, we were unable to adjust for the proportion of AD individuals awake at each hour60, and unable to assess how different factors such as social isolation, occupational problems, alcohol consumption and access to weapons acted either alone or in combination to increase the risk of suicide.

Several directions are available for future research. Considering the novel findings in this study, an attempt should be made to replicate these findings. Future studies should also account for the role of associated factors such as sleep continuity disturbance, circadian patterns of alcohol metabolism and executive functioning, and how psychological stress and social problems interact with alcohol use to increase risk of suicide.

Conclusion

The peak incidence of suicide among AD individuals was later in the day for those who were intoxicated than those with moderate or no recent alcohol consumption. In addition, intoxication in the evening may represent a greater risk for suicide, particularly using lethal means such as firearms.

Clinical Points.

We sought to identify periods of increased vulnerability to suicide during the 24-hour period in alcohol dependent individuals, a population at a higher risk for suicide, in order to optimize suicide prevention efforts

More intoxicated individuals as compared to non-intoxicated persons committed suicide between 20:01–00:00 hours and they had more associated risk and protective factors for intoxication

Acknowledgments:

We thank the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, GA for providing access to the NVDRS dataset. We also express our gratitude to the following individuals who helped with the data analysis and also provided intellectual assistance with the draft: 1) Dr. Ninad Chaudhary, MBBS MPH, University of Alabama at Birmingham; and, 2) Dr. Kachina Allen PhD, Princeton University. Neither Dr. Chaudhary not Dr. Allen have any conflict of interest with the manuscript draft. The content of this publication does not represent the views of the University of Pennsylvania, Department of Veterans Affairs, the United States Government, or any other institution. Some of the results from this study were presented at the Sleep 2016 annual meeting in Denver, CO.

Funding/Support: The study was not supported by any independent grant funding. Partial salary support was provided by the following grants (grant awardee): VA grant IK2CX000855 (S.C.), NIH grants K23 HL110216 and NIH R21 ES022931 (M.A.G.); 4R01AG041783 (M.L.P.) and 1R56AG050620 (M.L.P.); 5R01AA023192 (H.R.K.) and 4R01AA021164 (H.R.K.).

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interests: The authors certify that they have no actual or potential conflict of interest with this investigation.

References

- 1.CDC. Preventing suicide. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/Features/PreventingSuicide/index.html. Accessed May 15, 2017.

- 2.Curtin SC, Warner M, Hedegaard H. Increase in Suicide in the United States, 1999–2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2016(241):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crump C, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, Winkleby MA. Sociodemographic, psychiatric and somatic risk factors for suicide: a Swedish national cohort study. Psychol Med. 2014;44(2):279–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heikkinen ME, Isometsa ET, Marttunen MJ, Aro HM, Lonnqvist JK. Social factors in suicide. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167(6):747–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang SS, Stuckler D, Yip P, Gunnell D. Impact of 2008 global economic crisis on suicide: time trend study in 54 countries. BMJ. 2013;347:f5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milner A, Spittal MJ, Pirkis J, LaMontagne AD. Suicide by occupation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;203(6):409–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haukka J, Suominen K, Partonen T, Lonnqvist J. Determinants and outcomes of serious attempted suicide: a nationwide study in Finland, 1996–2003. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(10):1155–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pokorny AD. Prediction of suicide in psychiatric patients. Report of a prospective study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40(3):249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kontaxakis VP, Christodoulou GN, Mavreas VG, Havaki-Kontaxaki BJ. Attempted suicide in psychiatric outpatients with concurrent physical illness. Psychother Psychosom. 1988;50(4):201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juurlink DN, Herrmann N, Szalai JP, Kopp A, Redelmeier DA. Medical illness and the risk of suicide in the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(11):1179–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helmkamp JC. Occupation and suicide among males in the US Armed Forces. Ann Epidemiol. 1996;6(1):83–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tidemalm D, Langstrom N, Lichtenstein P, Runeson B. Risk of suicide after suicide attempt according to coexisting psychiatric disorder: Swedish cohort study with long term follow-up. BMJ. 2008;337:a2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mukamal KJ, Kawachi I, Miller M, Rimm EB. Drinking frequency and quantity and risk of suicide among men. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42(2):153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.CDC. Toxicology testing and results for suicide victims - 13 states, 2004. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(46):1245–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berglund M, Ojehagen A. The influence of alcohol drinking and alcohol use disorders on psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22(7 Suppl):333S–345S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klatsky AL, Armstrong MA. Alcohol use, other traits, and risk of unnatural death: a prospective study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1993;17(6):1156–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andreasson S, Allebeck P, Romelsjo A. Alcohol and mortality among young men: longitudinal study of Swedish conscripts. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1988;296(6628):1021–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borges G, Cherpitel CJ, MacDonald S, Giesbrecht N, Stockwell T, Wilcox HC. A case-crossover study of acute alcohol use and suicide attempt. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65(6):708–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hedden SL, Kennet J, Lipari R, et al. Behavioral Health Trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. SAMHSA;2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy GE, Wetzel RD. The lifetime risk of suicide in alcoholism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47(4):383–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller WR, Tonigan JS, Longabaugh R. The Drinker Inventory Of Consequences (DrInC): An Instrument for Assessing Adverse Consequences of Alcohol Abuse. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Project MATCH Monograph Series 1995; Available from: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/ProjectMatch/match04.pdf]. Accessed May 15, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mannelli P, Pae CU. Medical comorbidity and alcohol dependence. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007;9(3):217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(8):807–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams P, Tansella M. The time for suicide. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1987;75(5):532–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altamura C, VanGastel A, Pioli R, Mannu P, Maes M. Seasonal and circadian rhythms in suicide in Cagliari, Italy. J Affect Disord. 1999;53(1):77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Preti A, Miotto P. Diurnal variations in suicide by age and gender in Italy. Journal of affective disorders. 2001;65(3):253–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Houwelingen CA, Beersma DG. Seasonal changes in 24-h patterns of suicide rates: a study on train suicides in The Netherlands. Journal of affective disorders. 2001;66(2):215–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erazo N, Baumert J, Ladwig KH. Sex-specific time patterns of suicidal acts on the German railway system. An analysis of 4003 cases. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;83(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vollen KH, Watson CG. Suicide in relation to time of day and day of week. American Journal of Nursing. 1975;75(2):263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gallerani M, Avato F, Dal Monte D, Caracciolo S, Fersini C, Manfredini R. The time for suicide. Psychological medicine. 1996;26(04):867–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barraclough BM. Time of day chosen for suicide. Psychological Medicine. 1976;6(2):303–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maldonado G, Kraus JF. Variation in Suicide Occurrence by Time of Day, Day of the Week, Month, and Lunar Phase. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior. 1991;21(2):174–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Welte JW, Abel EL, Wieczorek W. The role of alcohol in suicides in Erie County, NY, 1972–84. Public Health Rep. 1988;103(6):648–652. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prasanna CA, Gandhibabu R, Asok Kumar M. Risk Factors in Suicide among Male Alcohol Dependents. Journal of Evolution of Medical and Dental Sciences. 2014;3(52):12073–12088. [Google Scholar]

- 35.CDC. National Violent Death Reporting system (NVDRS). Violence Prevention 2013; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/nvdrs/]. Accessed May 15, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hempstead KA, Phillips JA. Rising suicide among adults aged 40–64 years: the role of job and financial circumstances. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(5):491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.NIAAA. Drinking Levels Defined. http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking, 2017.

- 38.Lange JE, Voas RB. Defining binge drinking quantities through resulting BACs. Annu Proc Assoc Adv Automot Med. 2000;44:389–404. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caetano R, Kaplan MS, Huguet N, et al. Precipitating Circumstances of Suicide and Alcohol Intoxication Among U.S. Ethnic Groups. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39(8):1510–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.NVDRS. National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS): Guidelines for data users.: CDC; 2013:1–225. [Google Scholar]

- 41.SAS© [computer program]. Version 9.4 for Windows Cary, NC, USA: SAS Institute Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brick J, Pohorecky LA, Faulkner W, Adams MN. Circadian variations in behavioral and biological sensitivity to ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1984;8(2):204–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sturtevant RP, Garber SL. Circadian rhythm of blood ethanol clearance rates in rats: response to reversal of the L/D regimen and to continuous darkness and continuous illumination. Chronobiol Int. 1988;5(2):137–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sher L Alcohol consumption and suicide. QJM. 2006;99(1):57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Danel T, Touitou Y. Chronobiology of alcohol: from chronokinetics to alcohol-related alterations of the circadian system. Chronobiol Int. 2004;21(6):923–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sher L Risk and protective factors for suicide in patients with alcoholism. ScientificWorldJournal. 2006;6:1405–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Preuss UW, Schuckit MA, Smith TL, et al. Comparison of 3190 alcohol-dependent individuals with and without suicide attempts. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2002;26(4):471–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daly M, Delaney L, Doran PP, Maclachlan M. The role of awakening cortisol and psychological distress in diurnal variations in affect: a day reconstruction study. Emotion. 2011;11(3):524–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arnedt JT, Rohsenow DJ, Almeida AB, et al. Sleep following alcohol intoxication in healthy, young adults: effects of sex and family history of alcoholism. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2011;35(5):870–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murphy MJ, Peterson MJ. Sleep Disturbances in Depression. Sleep Med Clin. 2015;10(1):17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sharma T, Guski LS, Freund N, Gotzsche PC. Suicidality and aggression during antidepressant treatment: systematic review and meta-analyses based on clinical study reports. BMJ. 2016;352:i65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Courtet P, Jaussent I, Lopez-Castroman J, Gorwood P. Poor response to antidepressants predicts new suicidal ideas and behavior in depressed outpatients. European neuropsychopharmacology : the journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;24(10):1650–1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zalsman G, Hawton K, Wasserman D, et al. Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(7):646–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brent DA. Antidepressants and Suicidality. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(3):503–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Braun C, Bschor T, Franklin J, Baethge C. Suicides and Suicide Attempts during Long-Term Treatment with Antidepressants: A Meta-Analysis of 29 Placebo-Controlled Studies Including 6,934 Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Psychother Psychosom. 2016;85(3):171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bielefeldt AO, Danborg PB, Gotzsche PC. Precursors to suicidality and violence on antidepressants: systematic review of trials in adult healthy volunteers. J R Soc Med. 2016;109(10):381–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Case A, Deaton A. Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(49):15078–15083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Isacsson G, Bergman U, Rich CL. Antidepressants, depression and suicide: an analysis of the San Diego study. J Affect Disord. 1994;32(4):277–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marzuk PM, Tardiff K, Leon AC, et al. Use of prescription psychotropic drugs among suicide victims in New York City. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(10):1520–1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Perlis ML, Grandner MA, Brown GK, et al. Nocturnal Wakefulness as a Previously Unrecognized Risk Factor for Suicide. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(6):e726–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]