Abstract

Background

Transcatheter stent therapy is as effective as surgery in producing acute hemodynamic improvement in patients with coarctation of aorta (COA). However, left ventricular (LV) remodeling after transcatheter COA intervention has not been systematically investigated. The purpose of this retrospective cohort study was to compare remodeling of LV structure and function after transcatheter stent therapy vs surgical therapy for COA.

Methods

LV remodeling was assessed at 1, 3 and 5-years post-intervention using: LV mass index (LVMI), LV end-diastolic dimension, LV ejection fraction, LV global longitudinal strain (LVGLS), LV e’ and E/e’.

Results

There were 44 and 128 patients in the transcatheter and surgical groups respectively. Compared to the surgical group, the transcatheter group had less regression of LVMI (−4.6[95%CI −5.5 - −3.7] vs −7.3[95%CI −8.4 - −6.6] g/m2, p<0.001), less improvement in LVGLS (2.1[95%CI 1.8 to 2.4] vs 2.9[95%CI 2.6 – 3.2]%, p=0.024) and e’ (1.0 [95%CI 0.7–1.2] vs 1.5 [95%CI 1.3–1.7] cm/s, p=0.009) at 5 years post-intervention. Exploratory analysis showed a correlation between change in LVMI and LVGLS, and between change in LVMI and e’, and this correlations were independent of the type of intervention received.

Conclusions

Transcatheter stent therapy was associated with less remodeling of LV structure and function during mid-term follow-up. As transcatheter stent therapy become more widely used in the adult COA population, there is a need for ongoing clinical monitoring to determine if these observed differences in LV remodeling translates to differences in clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Coarctation of aorta, Transcatheter stent therapy, Left ventricular hypertrophy, Left ventricular remodeling

INTRODUCTION

Coarctation of aorta (COA) is the primary diagnosis in 10% of adults with congenital heart disease, and it is associated with premature cardiovascular mortality.1, 2 COA is characterized by vasculopathy, endothelial dysfunction, and an increased risk of coronary artery disease which ultimately results in maladaptive structural changes in the left ventricle (LV) such as hypertrophy, ischemia, and fibrosis leading to increased risk of heart failure.3–7 These maladaptive structural changes may lead to irreversible LV dysfunction and cardiovascular mortality if untreated over time.3–7 Surgical COA repair results in an acute reduction in LV pressure overload, which interrupts this pathophysiologic process, and may triggered reverse remodeling of LV structure and function.2, 8 It is postulated that the improved long-term survival after COA repair, especially when performed prior to irreversible LV dysfunction, is mediated through this mechanism.2, 8

Transcatheter stent therapy is a safe, effective and less invasive alternative to surgery in COA patients with anatomy suitable for transcatheter intervention, and this practice is based on robust data demonstrating a comparable acute hemodynamic improvement after transcatheter stent therapy.9–13 However unlike surgical therapy which has robust long-term outcome data, there are limited long-term clinical and hemodynamic outcome data after transcatheter stent therapy.9–13 It is postulated that the ‘rigid’ structure of the stent will affect the compliance and flow characteristics of the thoracic aorta, but its clinical relevance such as the net effect on LV afterload and LV reverse remodeling has not been studied.4, 14 The purpose of this study was, therefore, to compare remodeling of LV structure and function for patients undergoing transcatheter stent therapy vs surgical therapy for COA.

METHODS

Study Population

Adult patients (age ≥18 years) that underwent COA repair at Mayo Clinic Rochester, Minnesota from January 1, 2000 through December 31, 2018 were identified from the electronic health records. From this cohort, we excluded the following patients: (1) Patients that had extra-anatomic repair (ascending-to-descending aorta bypass graft) because it was not feasible to reliably assess residual COA gradient post repair. (2) Patients that underwent transcatheter or surgical therapy for the management of aortic aneurysm/pseudo-aneurysm. (3) Patients with significant aortic valve disease defined as prosthetic aortic valve, native aortic valve peak velocity >2 m/sec or >mild aortic regurgitation. (4) Patients with significant mitral valve disease defined as prosthetic mitral valve, native mitral valve mean gradient >3 mmHg or >mild mitral regurgitation. The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board approved this study and waived informed consent for patients that provided research authorization. The choice of surgical versus transcatheter therapy was based on the decision of the primary cardiologist. The patients with discrete COA were typically referred for transcatheter therapy, while those with long segment stenosis and hypoplastic arch were typically referred for surgical therapy.

Study Design

This is a retrospective cohort study comparing remodeling of LV structure, systolic function, and diastolic function after transcatheter stent therapy vs surgical therapy. For LV structure, we assessed LV hypertrophy using LV mass index (LVMI) and LV size using LV end-diastolic dimension (LVEDD). LV systolic function was assessed using LV ejection fraction (LVEF) and LV global longitudinal strain (LVGLS). LV diastolic function was assessed using mitral annular tissue Doppler early velocity (e’) and ratio of mitral inflow pulsed wave Doppler early velocity and e’ (E/e’). LV remodeling was assessed at 3 time points: 1-year, 3-year and 5-year post-intervention. The New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification was used to define symptomatic status, and a patient was considered asymptomatic if in NYHA I or symptomatic if in NYHA II-IV.

Subgroup analyses were performed to assess LV remodeling in the patients without reintervention during follow-up, in patients that had complete follow-up at all intervals, and in the patients that had follow-up ≥5 years post intervention. Exploratory analysis was performed to assess the relationship between remodeling of LV structure and remodeling of LV function.

Echocardiography

Two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography was performed according to contemporary guidelines.15 All digital images were reviewed and off-line measurements performed by two experienced sonographers (JW and KT). The last echocardiogram performed within 1 month prior to intervention was used at the baseline echocardiogram. The echocardiograms performed at 9–15 months, 33–39 months, and 57–63 months were used for the 1-year, 3-year and 5-year follow-up respectively. Using the pre-intervention echocardiogram as the reference, LV remodeling during follow-up was calculated as the difference between pre-intervention and post-intervention (1-year, 3-year, and 5-year) echocardiographic indices.

LVEDD, LVMI, LVEF were assessed using 2-D echocardiographic linear measurements of LV diastolic diameter, systolic diameter and wall thickness obtained from the parasternal long-axis view.15 Mitral E velocity and e’ velocity were measured from the apical 4-chamber view, and we used the averaged value of the septal and lateral e’ velocities for this study.16

LV speckle tracking strain imaging was obtained using Vivid E9 and E95 (General Electric Co, Fairfield, Connecticut) with M5S and M5Sc-D transducers (1.5–4.6 MHz) at frame rate of 40 to 80 Hz.17 Three-beat cine-loop clips were obtained from parasternal short-axis views at the papillary muscle level and from 3 apical views (2-chamber, 3-chamber, and 4-chamber). These images were exported and then analyzed offline with syngo VVI software (Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc., Malvern, Pennsylvania). Offline analysis involved manual endocardial to mid-wall tracing of a single frame at end-systole by a point-click approach, with a region of interest that covers at least 90% of the myocardial wall thickness. The periodic displacement of the tracing was automatically tracked in subsequent frames. Tissue velocity was determined by the software, according to a shift of the points divided by time between B-mode frames, and the software automatically calculated peak longitudinal systolic strain and strain rate from the velocity.

Transcatheter Therapy

Transcatheter balloon dilation and stent implantation were performed via femoral artery access under general anesthesia. Pressure measurements were obtained proximal and distal to the site of COA. Contrast angiography was performed for measurements of the aortic arch, smallest dimension at COA site and descending aorta at the level of the diaphragm. The procedural details for transcatheter COA therapy have been described.11–13 Procedural complication was defined as aortic wall injury (dissection, intimal tear, aneurysm), femoral/access site hematoma, and death prior to hospital discharge.11–13 Reintervention was defined as re-do surgical COA repair, transcatheter balloon dilation or stent therapy. Reintervention was classified as anticipated reintervention if it was performed as part of a staged approach or unanticipated reintervention if it was performed because of recurrent COA.11–13

Statistical Analysis

Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile range), count (%) or mean difference (95% confidence interval [CI]). Between-group differences were assessed with unpaired t-test, Wilcoxon ranked sum test, and Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. We used propensity score method to adjust for between-group differences in baseline characteristics. First we calculated a propensity score for treatment (transcatheter stent therapy vs surgical therapy) using logistic regression, and adjusting for the following variables: current age, sex, aortic valve peak velocity, aortic isthmus peak velocity and baseline systolic blood pressure. The propensity score was then used in all regression analyses. Linear regression analysis was used to assess correlation between continuous variable, and correlation coefficients (r) were compared using Meng test. A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with JMP software (version 14.1.0; SAS Institute Inc, Cary NC).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

The cohort comprised of 172 patients of which 44 patients received transcatheter stent therapy while 128 patients received surgical therapy. The indication for intervention was for recurrent COA in 35 (81%) and 102 (80%) patients in the transcatheter stent therapy and surgical groups respectively. Compared to the surgical group, the transcatheter group was younger, had higher COA peak gradient, and a lower prevalence of long segment COA (Table 1).

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics

| Stent (n=44) | Surgery (n=128) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 26 (18–42) | 32 (22–45) | 0.012 |

| Male | 26 (59%) | 74 (58%) | 0.879 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28±3 | 29±5 | 0.328 |

| SBP, mmHg | 134±18 | 140±21 | 0.109 |

| ULE-SBP gradient, mmHg | 36±11 | 31±19 | 0.218 |

| Hypertension | 35 (80%) | 109 (85%) | 0.282 |

| NYHA II-IV | 37 (84%) | 116 (91%) | 0.233 |

| Peak VO2, % | 66±12 [n=31] | 64±15 [n=88] | 0.504 |

| SBP at peak exercise, mmHg | 191±26 [n=31] | 187±39 [n=88] | 0.597 |

| Medications | |||

| Thiazide diuretics | 6 (14%) | 24 (18%) | 0.554 |

| Beta blockers | 15 (34%) | 46 (36%) | 0.723 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 6 (14%) | 13 (10%) | 0.596 |

| ACEI/ARB | 15 (34%) | 41 (32%) | 0.733 |

| Use of anti-hypertensive drug | 36 (82%) | 108 (84%) | 0.128 |

| Use of ≥2 anti-hypertensive drug | 10 (23%) | 32 (25%) | 0.326 |

| COA hemodynamics | |||

| COA peak velocity, (CWD) m/s | 3.4±0.8 | 3.2±0.9 | 0.043 |

| COA proximal velocity (PWD), m/s | 1.0±0.3 | 0.9±0.3 | 0.653 |

| COA peak gradient, mmHg | 47±14 | 43±16 | 0.041 |

| COA corrected peak gradient, mmHg | 29±9 | 24±6 | 0.037 |

| COA mean gradient, mmHg | 27±13 | 25±14 | 0.396 |

| Thoracic aorta dimensions | |||

| Proximal arch, mm | 20±3 | 18±2 | 0.093 |

| Distal arch, mm | 18±3 | 16±4 | 0.087 |

| Isthmus, mm | 9±3 | 8±2 | 0.663 |

| Descending aorta at diaphragm, mm | 17±2 | 17±3 | 0.254 |

| Isthmus/descending aorta ratio | 0.7±0.1 | 0.6±0.1 | 0.109 |

| Hypoplastic arch* | 19 (43%) | 56 (44%) | 0.773 |

| Long segment stenosis** | 8 (18%) | 46 (36%) | 0.019 |

COA: Coarctation of aorta; SBP: Systolic blood pressure; ULE-SBP: Upper-to-lower extremity systolic blood pressure gradient; ACEI: Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB: Angiotensin II receptor blocker; CWD: Continuous wave Doppler; PWD: Pulsed wave Doppler; NYHA: New York Heart Association; VO2: Oxygen consumption.

Only VO2 data from treadmill exercise test with respiratory exchange ratio >1.0 performed within 6 months of the date of intervention were analyzed

Data expressed a mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile range) or count (%)

Hypoplastic aortic arch was defined as a ratio of the distal transverse arch dimension divided by descending aorta measured at the level of the diaphragm <0.6.13

Discrete and long segment COA were defined as COA segments measuring ≤5 mm vs >5 mm respectively. 13

LV Structure and Function

Table 2 shows a between-group comparison of echocardiographic indices of LV structure, systolic function, and diastolic function. Compared to the surgical group, the transcatheter group had less LV hypertrophy (LVMI 102±24 g/m2 vs 109±29, p=0.011). Otherwise, there were no other significant between-group differences. Interestingly, both groups had reduced LVGLS (−15±4 in the transcatheter group vs −14±5 in the surgical group, p=0.118) despite having normal LVEF (63±6 vs 62±7%) suggesting the presence of subclinical LV systolic dysfunction.

Table 2:

LV Structure and Function

| Stent (n=44) | Surgery (n=128) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LV structure | |||

| LV end-diastolic dimension, mm | 50±5 | 50±6 | 0.126 |

| LV end-systolic dimension, mm | 31±6 | 30±6 | 0.392 |

| LV mass index, g/m2 | 102±24 | 109±29 | 0.011 |

| LV systolic function | |||

| LV ejection fraction, % | 63±6 | 62±7 | 0.494 |

| LV global longitudinal strain, % | (-)15±4 | (-)14±5 | 0.118 |

| LV diastolic function | |||

| Mitral E velocity, m/s | 1.1±0.3 | 1.2±0.3 | 0.314 |

| Septal e’ velocity, cm/s | 9±3 | 9±4 | 0.402 |

| Lateral e’ velocity, cm/s | 12±4 | 11±5 | 0.328 |

| Averaged e’ velocity, cm/s | 11±4 | 10±5 | 0.118 |

| Averaged E/e’ | 11±3 | 12±3 | 0.088 |

| Other indices | |||

| LA volume index, ml/m2 | 29±8 | 31±10 | 0.232 |

| LV end-diastolic volume index, ml/m2 | 63±10 | 65±12 | 0.322 |

| LV end-systolic volume index, ml/m2 | 26±7 | 28±9 | 0.182 |

LV: Ventricle; LA: Left atrium; E: Mitral early diastolic velocity; e’: Mitral annular tissue Doppler early velocity;

Data expressed a mean ± standard deviation

Interventions

The types of stents and surgical repair techniques used in this cohort are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Among the patients that received transcatheter stent therapy, there was a significant reduction in COA peak-to-peak gradient from 22 (12–29) to 3 (0–6) mmHg (p<0.001) with corresponding increase in aortic isthmus dimension from 9±3 to 17±2 (p=0.002) after stent implantation. There were no procedural complications. Both groups had similar acute reduction in Doppler peak gradient, Doppler gradient mean, and systolic blood pressure (Table 3). The length of hospital stay was significantly longer in the surgical group, 5 (4–7) vs 1 (1–2) days, p<0.001, and there were no in-hospital deaths in both groups.

Table 3:

Doppler Gradient and Blood Pressure at Hospital Discharge

| Transcatheter group (N=44) | Surgical group (N=128) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doppler peak gradient at discharge, mmHg | 18±5 | 15±4 | 0.054 |

| Acute reduction in peak gradient, mmHg | 28 (20–35) | 27 (23–31) | 0.655 |

| Doppler mean gradient at discharge, mmHg | 9±4 | 8±3 | 0.484 |

| Acute reduction in mean gradient, mmHg | 18 (12–23) | 17 (13–226 phd1) | 0.412 |

| SBP at discharge, mmHg | 122±7 | 125±8 | 0.367 |

| Acute reduction in SBP, mmHg | 12 (9–15) | 15 (10–19) | 0.216 |

SBP: systolic blood pressures. Data expressed a mean ± standard deviation, mean difference (95% confidence interval)

There were no reinterventions in the surgical group. On the other hand, 3 (7%) of the 44 patients in the transcatheter stent therapy group had reinterventions. These reinterventions involved re-dilation of a Palmaz Genesis 2910 XD stent at 9 months post-implantation (anticipated reintervention), re-dilation of a 36 mm EV3 Max LD stent at 12 months post-implantation (anticipated reintervention), and implantation of a second stent at 91 months post implantation of Palmaz Genesis 2910 XD stent (unanticipated reintervention).

Remodeling of LV Structure and Function

The median follow-up was longer in the surgical group, 63 (41–94) vs 46 (27–81) months, p<0.001. All the patients in transcatheter group had echocardiographic follow-up 1 year, while 38 (86%) and 21 (48%) patients had follow-up at 3 and 5 years respectively. In the Surgical group, 126 (98%), 96 (75%) and 79 (62%) had echocardiographic follow-up at 1, 3, and 5 years respectively. There was no significant between-group differences in aortic valve peak velocity at baseline (1.4±0.2 vs 1.4±0.3 mmHg, p=0.943), 1-year (1.5±0.2 vs 1.5±0.3 mmHg, p=0.911), 3-year (1.5±0.3 vs 1.6±0.3 mmHg, p=0.125), and 5-year (1.5±0.3vs 1.5±0.3 mmHg, p=0.268) follow-up. This suggests that any observed between-group difference in LV remodeling was not due to LVOT obstruction.

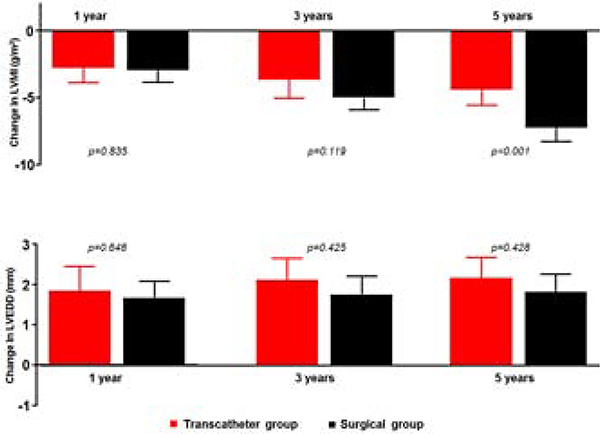

There was a net regression of LV hypertrophy during follow-up, and the rate of regression was similar between the 2 groups at 1 and 3 years, but became more pronounced in the surgical group at 5 years (−7.3 [95%CI −8.4 - −6.6] vs −4.6 [95%CI −5.5 - −3.7] g/m2, p<0.001). Both groups had a similar net increase in LV size, without significant between-group differences in the extent of LV size remodeling at all stages of follow-up, Central illustration.

Central illustration: Box-and-whisker plot comparing changes in left ventricular mass index (LVMI) and left ventricular end-diastolic dimension (LVEDD) between the transcatheter stent therapy group (red) and surgical group (black). Data expressed as mean difference (95% confidence interval).

Figure highlights between-group differences in LVMI and LVEDD

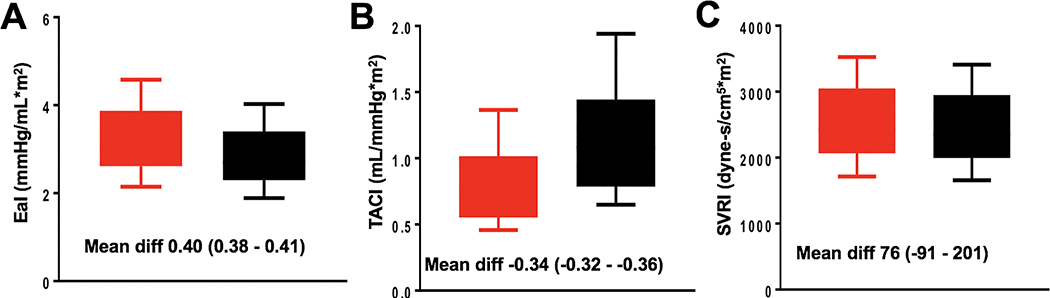

There was net improvement in LVGLS during follow-up, and the rate of improvement was similar at 1 and 3 years post intervention, but became significantly higher in the surgical group at 5 years (2.9 [95%CI 2.6–3.2] vs 2.1 [95%CI 1.8–2.4] %, p=0.024), Figure 1. In contrast, there was no net improvement in LVEF in both groups at all stages of follow-up.

Figure 1: Box-and-whisker plot comparing changes in left ventricular global longitudinal strain (LVGLS) and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) between the transcatheter stent therapy group (red) and surgical group (black).

Figure highlights between-group differences in LVGLS and LVEF

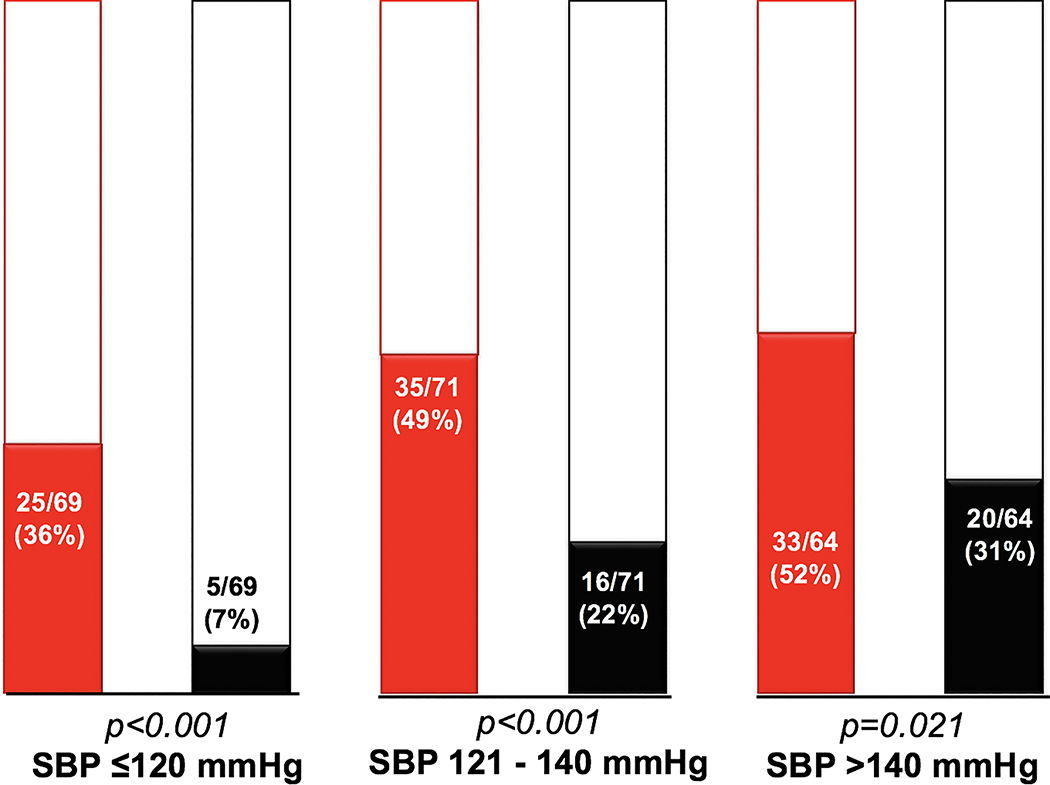

The transcatheter group had more significant improvement in LV myocardial relaxation at 1 year as shown by a more prominent improvement in averaged e’ (0.9 [95%CI 0.7–1.1] vs 0.4 [95%CI 0.2–0.6] cm/s), p=0.032. The net improvement in averaged e’ plateaued at 3 years in the transcatheter group, but continued to increase in the surgical group resulting in a significantly higher net increase in the surgical group at 5 years (1.5 [95%CI 1.3–1.7] vs 1.0 [95%CI 0.7–1.2] cm/s, p=0.009), Figure 2. In contrast, there was no net improvement in LV filling pressure (averaged E/e’) in both groups at all stages of follow-up. Using the pre-intervention left atrial volume index as the reference, there was significant reduction in at 3-year (31±10 vs 28±6, ml/m2, p=0.019) and 5-year (31±10 vs 28±6, ml/m2, p=0.024) follow-up in the surgical group. A similar reduction was also observed at 3-year (29±8 vs 27±6, ml/m2, p=0.188) and 5-year (31±10 vs 27±8, ml/m2, p=0.437) follow-up in the transcatheter group but this was not statistically significant likely due to a smaller sample size. Concordant with the observed changes in left atrial volume and left heart diastolic function indices, there were fewer symptomatic patients (NYHA II-IV) in the surgical group during follow-up (pre-intervention 116/128 [91%] vs 1-year follow-up 11/126 [9%] vs 3-year follow-up 9/96 [9%], vs 5-year follow-up 7/79 [9%], p<0.001). A similar reduction in the number of symptomatic patients was also observed in the transcatheter group (pre-intervention 37/44 [84%] vs 1-year follow-up 3/44 [7%] vs 3-year follow-up 4/38 [11%], vs 5-year follow-up 2/21 [10%], p<0.001).

Figure 2: Box-and-whisker plot comparing changes in left ventricular e’ velocity and E/e’ between transcatheter stent therapy group (red) and surgical group (black).

Figure highlights between-group differences in e’ and E/e’

Subgroup Analyses

Three pre-specified sets of subgroup analyses were performed. First, we excluded the 3 patients that have reinterventions, and then repeated the between-group comparisons of LV remodeling in all 6 domains (LVMI, LVEDD, LVEF, LVGLS, e’ and E/e’). The remodeling of LV structure and function observed in this subgroup was similar to the results observed in the entire cohort in all 6 domains at all stages of follow-up.

Another subgroup analysis was performed in the patients that had assessment at all 3 intervals (transcatheter group n=21 and surgical group n=79). There was no significant between-group differences in systolic blood pressure at baseline (138±14 vs 133±13 mmHg, p=0.143), 1-year (125±10 vs 122±8 mmHg, p=0.207), 3-year (120±8 vs 123±7 mmHg, p=0.121), and 5-year (120±6 vs 123±8 mmHg, p=0.129), follow-up. Similarly, there was no significant between-group differences in aortic isthmus (COA) peak velocity at baseline (3.3±0.5 vs 3.3±0.8 m/s, p=0.983), 1-year (1.9±0.2 vs 2.0±0.3 m/s, p=0.071), and 3-year (1.9±0.3 vs 2.0±0.4 m/s, p=0.211) follow-up. However the transcatheter group had a higher aortic isthmus peak velocity at 5-year follow-up (1.9±0.3 vs 2.1±0.4 m/s, p=0.013). Similar to the pattern observed in the entire cohort, the rate of regression of LVMI was similar between the 2 groups at 1 and 3 years, but became more pronounced in the surgical group at 5 years (−7.1 [95%CI −8.7 - −6.2] vs −4.5 [95%CI −5.8 - −3.4] g/m2, p=0.003). We observed a negative correlation (r= −0.34, p=0.042) when we plotted aortic isthmus peak velocity vs change in LVMI at each follow-up interval, suggesting that the between-group differences in the rate of regression of LVMI at 5-years may be related to LV pressure overload from residual/recurrent coarctation.

Next we analyzed only the patients that had follow-up beyond 5 years, and this comprised of 21 patients in the transcatheter group and 79 patients in the surgical group. Compared to the patients without 5-year follow-up (n=72), the patients with 5-year follow-up (n=100) were older 31 (22–43) vs 27 (19–41) years, p=0.046, but otherwise there were no other significant between-group differences in the baseline clinical and echocardiographic characteristics. Again, the results from the subgroup analyses were similar to that of the entire cohort (Supplementary Table 2). Both groups had similar regression of LVMI at 1 and 3 years but the remodeling in the transcatheter group seemed to plateau afterwards in contrast to the surgical group that had ongoing remodeling up to 5 years. Similarly the temporal improvement in LVGLS and e’ also plateaued within the first 3 years in the transcatheter group, in contrast to the surgical group that had ongoing remodeling up to 5 years.

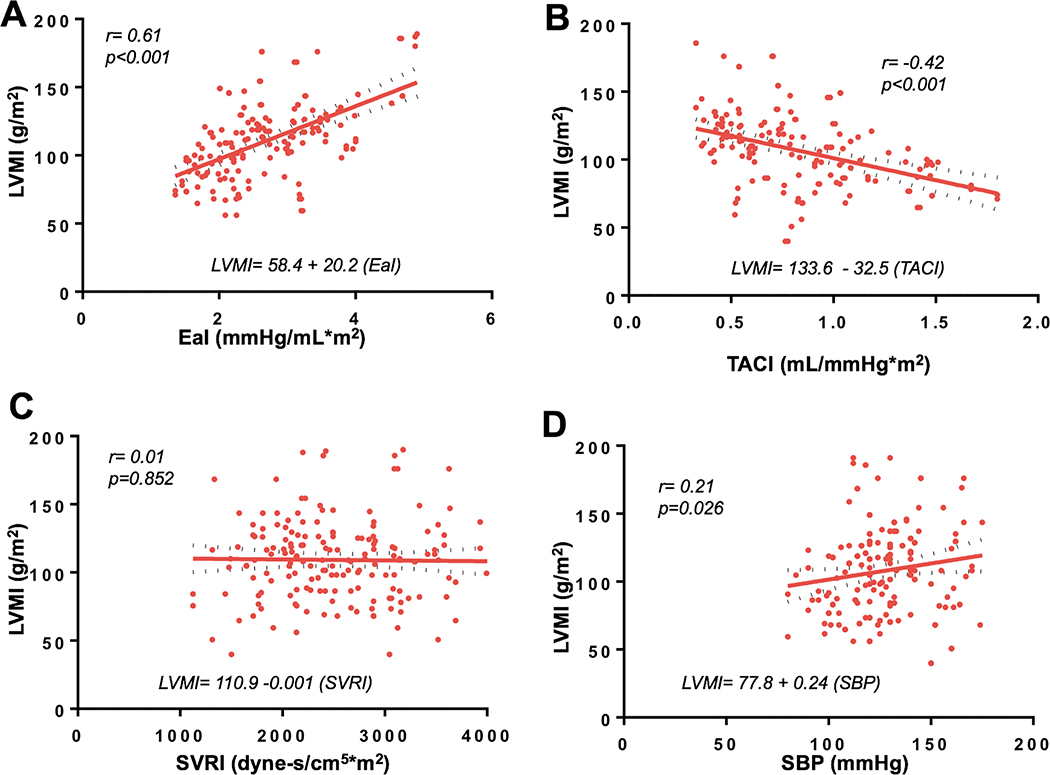

Exploratory analysis showed a correlation between change in LVMI and LVGLS, and also a correlation between change in LVMI and e’ after adjustment for propensity score, Figure 3. The strength of correlation was not different between the 2 groups both for LVMI vs LVGLS relationship (Meng test p=0.105) and LVMI vs e’ relationship (Meng test p=0.344). This suggests that the relationship between remodeling of LV function and remodeling LV structure was independent of the type of intervention received.

Figure 3: Linear regression of changes in LVMI vs changes in LVGLS (A), and changes in LVMI vs changes in LV e’ (B). Change in LVMI was plotted as absolute values (even the net change was negative).

Figure highlights change in LVMI per unit change in LVGLS and LV e’

DISCUSSION

Remodeling of LV Structure

In this cohort study comparing remodeling of LV structure and function after COA intervention, both the transcatheter and surgical groups had similar net regression of LV hypertrophy up to 3 years post intervention. Regression of LV hypertrophy plateaued in the transcatheter group afterwards while the surgical group had ongoing remodeling up to 5 years post-intervention. The LV size increased in both groups, without any between-group differences in the extent of remodeling.

Several studies have reported acute reduction in COA gradient, systolic blood pressure, and ongoing requirement for antihypertensive therapy after transcatheter stent therapy for native and recurrent COA.11, 13, 18–21 Some of the studies compared hemodynamic improvement between surgery and transcatheter stent therapy,13, 18, 22 some studies compared hemodynamic improvement between different types of stent,23 while other studies reported outcomes of specific stent types such as the Cheatham Platinum stent and the self-expandable uncovered stents.19, 21 All these studies provide robust evidence that transcatheter stent therapy is as effective as surgery in producing acute hemodynamic improvement after COA intervention. However LV adaptation to these hemodynamic improvements post transcatheter COA intervention, and how this compares to surgical therapy have not been systematically investigated, hence the current study.

COA creates LV pressure overload, and LV hypertrophy is barometer that reflects the severity and/or duration of LV pressure overload.3, 5 Regression of LV hypertrophy should therefore provide a good metric for assessing the net hemodynamic benefit from COA intervention.3–5 There are three potential explanations for the between-group difference in regression of LV hypertrophy observed in this study. One explantation is that the surgical group had more LV hypertrophy at baseline and hence had more regression of hypertrophy during follow-up. However, this may not be the only explanation because a subgroup analysis of patients that had 5-year follow-up showed that although both groups had similar LVMI prior to intervention; the surgical group had more significant regression LV hypertrophy at 5 years similar to the result from the entire cohort.

The second explanation is that, although both groups had similar residual COA gradient and systolic blood pressure immediately after intervention, the transcatheter group had a higher LV pressure overload during follow-up. Our speculation is supported by data from previous studies showing that transcatheter stent therapy was associated with more than 3-fold increase in the risk of reintervention during follow-up compared to surgery.24 Similar estimates of reintervention risk have also been reported in the Congenital Cardiovascular Interventional Study Consortium (CCISC) observational study and the more recent multicenter Coarctation of Aorta Stent Trial (COAST) 13, 19 However it is important to emphasize that some of these reinterventions were anticipated reinterventions either to deal with somatic growth in the younger patient or as part of a staged approach.

The third potential explanation may be related to the presence of residual systemic hypertension during follow-up which can occur in the absence of significant COA restenosis. In a long-term outcome study 404 patient that underwent surgical COA repair, 57% had persistent hypertension of which only 13% were related to COA restenosis.25 Although 57% of the cohort had persistent hypertension, only 25% of the patients remained on antihypertensive therapy after COA repair suggesting that persistent hypertension is an under-recognized and under-treated problem in this population.

Remodeling of LV Function

Both groups had net improvement in LV systolic and diastolic function as shown by improvement in LVGLS and e’, but no change in LVEF and LV filling pressures (E/e’). Similar to the pattern of remodeling for LVMI, the temporal improvement in LVGLS and e’ seemed to plateau after 3 years post intervention in the transcatheter stent group in contrast to the surgical group resulting in an overall better remodeling at 5 years in the surgical group. We postulate that the improvement in systolic and diastolic function may be related to regression of LV hypertrophy as shown by the correlation between changes in LVMI, LVGLS and e’. Since LV myocardial deformation and relaxation is related to LV afterload,26, 27 it will be logical to speculate that the surgical group had more regression of LVMI, and hence more improvement in LVGLS and e’ because they had lower LV afterload during follow-up.

Limitations

Several factors such as systemic hypertension, residual COA stenosis, and vascular/endothelial dysfunction affect LV afterload, and these factors typically changed over time. A limitation of this study was that we only assessed systolic blood pressure and residual COA stenosis post intervention, without factoring in potential temporal changes in these variables over time. Hence the current study lacks mechanistic data to explain the observed differences in remodeling of LV hypertrophy and function. Additionally we did not control for between-group differences in age and duration of hypertension, and these factors could potentially have influenced the observed results. The duration of follow-up was not long enough to assess for differences in clinical outcomes, hence it is unclear whether these statistically significant differences in LV remodeling indices will result in clinically significant differences in outcomes.

Conclusions

Although both transcatheter and surgical therapy resulted in a similar acute hemodynamic improvement, the transcatheter group had less regression of LV hypertrophy and less improvement in LV systolic and diastolic function indices during mid-term follow-up. The remodeling of LV structure correlated with remodeling of LV systolic and diastolic function indices. However these observed between-group differences in LV remodeling are subtle, and are of unclear clinical significance. Therefore as transcatheter stent therapy become more widely used in the adult COA population, there is a need for ongoing clinical monitoring to determine if these observed differences in LV remodeling translates to differences in clinical outcomes. Further studies are required to identify factors responsible for LV remodeling post intervention, and to explore medical and interventional strategies to promote normalization of the structure and function after COA intervention.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE (Competency in Medical Knowledge).

Coarctation of aorta (COA) creates maladaptive left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy and dysfunction, and the goal of COA intervention is to halt this pathophysiologic process. Reverse remodeling of LV structure and function should therefore provide a good metric for assessing the net hemodynamic benefit from COA intervention. In this study, we observed that compared to surgical COA repair, transcatheter stent therapy was associated with less regression of LV hypertrophy, and less improvement in LV systolic and diastolic function indices during mid-term follow-up.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK.

As transcatheter stent therapy become more widely used in the adult COA population, there is a need for ongoing clinical monitoring to determine if these observed differences in LV remodeling translates to differences in clinical outcomes. Further studies are required to identify factors responsible for LV remodeling post intervention, and to explore medical and interventional strategies to promote normalization of the structure and function after COA intervention.

Acknowledgement

James Welper and Katrina Tollefsrud for performing offline measurements of the echocardiographic indices used in this study.

Funding: Dr. Egbe is supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) grant K23 HL141448-01.

Abbreviations

- COA

Coarctation of aorta

- LV

Left ventricle

- LVMI

Left ventricular mass index

- LVEDD

Left ventricular end-diastolic dimension

- LVGLS

Left ventricular global longitudinal strain

- LVEF

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- e’

mitral annular tissue Doppler early velocity

- E/e’

ratio of mitral inflow pulsed wave Doppler early velocity and e’

- CI

Confidence interval

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: none

Disclosures: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zomer AC, Vaartjes I, van der Velde ET, et al. Heart failure admissions in adults with congenital heart disease; risk factors and prognosis. International journal of cardiology. 2013;168:2487–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown ML, Burkhart HM, Connolly HM, et al. Coarctation of the aorta: lifelong surveillance is mandatory following surgical repair. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013;62:1020–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rinnstrom D, Dellborg M, Thilen U, et al. Left ventricular hypertrophy in adults with previous repair of coarctation of the aorta; association with systolic blood pressure in the high normal range. International journal of cardiology. 2016;218:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lombardi KC, Northrup V, McNamara RL, Sugeng L and Weismann CG. Aortic stiffness and left ventricular diastolic function in children following early repair of aortic coarctation. The American journal of cardiology. 2013;112:1828–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Divitiis M, Pilla C, Kattenhorn M, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure, left ventricular mass, and conduit artery function late after successful repair of coarctation of the aorta. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2003;41:2259–2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egbe AC, Rihal CS, Thomas A, et al. Coronary Artery Disease in Adults With Coarctation of Aorta: Incidence, Risk Factors, and Outcomes. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e012056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pickard SS, Gauvreau K, Gurvitz M, Gagne JJ, Opotowsky AR, Jenkins KJ and Prakash A. A National Population-based Study of Adults With Coronary Artery Disease and Coarctation of the Aorta. The American journal of cardiology. 2018;122:2120–2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vriend JW and Mulder BJ. Late complications in patients after repair of aortic coarctation: implications for management. International journal of cardiology. 2005;101:399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stout KK, Daniels CJ, Aboulhosn JA,et al. 2018 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Adults With Congenital Heart Disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019;73:e81–e192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baumgartner H, Bonhoeffer P, et al. : ESC Guidelines for the management of grown-up congenital heart disease (new version 2010). European heart journal. 2010;31:2915–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forbes TJ, Garekar S, Amin Z, et al. Procedural results and acute complications in stenting native and recurrent coarctation of the aorta in patients over 4 years of age: a multi-institutional study. Catheterization and cardiovascular interventions. 2007;70:276–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forbes TJ, Moore P, Pedra CA, et al. Intermediate follow-up following intravascular stenting for treatment of coarctation of the aorta. Catheterization and cardiovascular interventions. 2007;70:569–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forbes TJ, Kim DW, Du W, et al. Comparison of surgical, stent, and balloon angioplasty treatment of native coarctation of the aorta: an observational study by the CCISC (Congenital Cardiovascular Interventional Study Consortium). Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2011;58:2664–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forbes TJ and Gowda ST. Intravascular stent therapy for coarctation of the aorta. Methodist DeBakey cardiovascular journal. 2014;10:82–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell C, Rahko PS, Blauwet LA, et al. Guidelines for Performing a Comprehensive Transthoracic Echocardiographic Examination in Adults: Recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2019;32:1–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagueh SF, Smiseth OA, Appleton CP, et al. Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2016;29:277–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voigt JU, Pedrizzetti G, Lysyansky P, et al. Definitions for a common standard for 2D speckle tracking echocardiography: consensus document of the EACVI/ASE/Industry Task Force to standardize deformation imaging. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2015;28:183–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeaw X, Murdoch DJ, Wijesekera V, Comparison of surgical repair and percutaneous stent implantation for native coarctation of the aorta in patients >/= 15 years of age. International journal of cardiology. 2016;203:629–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meadows J, Minahan M, McElhinney DB, McEnaney K, Ringel R and Investigators* C. Intermediate Outcomes in the Prospective, Multicenter Coarctation of the Aorta Stent Trial (COAST). Circulation. 2015;131:1656–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang L, Chua X, Rajgor DD, Tai BC and Quek SC. A systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes of transcatheter stent implantation for the primary treatment of native coarctation. International journal of cardiology. 2016;223:1025–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kische S, D’Ancona G, Stoeckicht Y, Ortak J, Elsasser A and Ince H. Percutaneous treatment of adult isthmic aortic coarctation: acute and long-term clinical and imaging outcome with a self-expandable uncovered nitinol stent. Circulation Cardiovascular interventions. 2015;8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haji Zeinali AM, Sadeghian M, Qureshi SA and Ghazi P. Midterm to long-term safety and efficacy of self-expandable nitinol stent implantation for coarctation of aorta in adults. Catheterization and cardiovascular interventions 2017;90:425–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Butera G, Manica JL, Marini D, Piazza L, Chessa M, Filho RI, Sarmento Leite RE and Carminati M. From bare to covered: 15-year single center experience and follow-up in transcatheter stent implantation for aortic coarctation. Catheterization and cardiovascular interventions 2014;83:953–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carr JA. The results of catheter-based therapy compared with surgical repair of adult aortic coarctation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2006;47:1101–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hager A, Kanz S, Kaemmerer H, Schreiber C and Hess J. Coarctation Long-term Assessment (COALA): significance of arterial hypertension in a cohort of 404 patients up to 27 years after surgical repair of isolated coarctation of the aorta, even in the absence of restenosis and prosthetic material. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2007;134:738–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kheiwa A, Aggarwal S, Forbes TJ, Turner DR and Kobayashi D. Impact of Transcatheter Intervention on Myocardial Deformation in Patients with Coarctation of the Aorta. Pediatr Cardiol. 2016;37:1590–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borlaug BA, Melenovsky V, Redfield MM, Kessler K, Chang HJ, Abraham TP and Kass DA. Impact of arterial load and loading sequence on left ventricular tissue velocities in humans. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;50:1570–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.