Abstract

Over the past decade there has been a surge of interest in the development of endocannabinoid (eCB)-based therapeutic approaches for the treatment of diverse neuropsychiatric conditions. Although initial preclinical and clinical development efforts focused on pharmacological inhibition of fatty-acid amide hydrolase to elevate levels of the eCB anandamide, more recent efforts have focused on inhibition of monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) to enhance signaling of the most abundant and efficacious eCB ligand, 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG). Here we review the biochemistry and physiology of 2-AG signaling and preclinical evidence supporting a role for this system in the regulation of anxiety-related outcomes and stress adaptation. We review preclinical evidence supporting MAGL inhibition for the treatment of affective, trauma and stress-related disorders, describe the current state of MAGL inhibitor drug development, and discuss biological factors that could affect MAGL inhibitor efficacy. Issues related to the clinical advancement of MAGL inhibitors are also discussed. We are cautiously optimistic, as the field of MAGL inhibitor development transitions from preclinical to clinical and theoretical to practical, that pharmacological 2-AG augmentation could represent a mechanistically novel therapeutic approach for the treatment of affective and stress-related neuropsychiatric disorders.

Keywords: cannabinoid, marijuana, anxiety, depression, endocannabinoid, Stress, amygdala

Introduction

Human interest in Cannabis plants has a centuries-long tradition and consumption of cannabis is increasing in the context of growing anti-prohibition movements at the state-level (1). Importantly, stress-coping, relaxation and tension reduction are highly cited cannabis use motives in the general population as well as in clinical populations suffering from anxiety and trauma-related disorders (2–5). In contrast, it has been only within recent decades that we have begun to understand the physiology and function of our endogenous cannabinoid (eCB) signaling systems in the modulation of mood and anxiety and in the regulation of stress adaptation (6–8). Indeed, a growing number of preclinical studies support the notion that harnessing the therapeutic potential of cannabinoid systems by enhancing eCB signaling could represent a novel strategy for the treatment of affective and trauma-related disorders (9, 10). The eCB system consists of 1) endogenous lipid ligands, anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoyl glycerol (2-AG) 2) G protein-coupled receptors, cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) and 2 (CB2) and 3) enzymes involved in biosynthesis, transportation and degradation of endogenous lipid ligands (11, 12). Although there are, in theory, a number of approaches to pharmacological augmentation of eCB signaling systems including direct cannabinoid receptor activation, receptor allosteric modulation, and inhibition of eCB reuptake; enzymatic eCB degradation inhibition has clearly emerged as the front-runner in this regard. Development of efficacious fatty-acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) inhibitors at the turn of the century, which increase central and peripheral AEA signaling (13), propelled this class of compounds into clinical trials for pain and addiction (14, 15), and human experimental studies of anxiety and stress-reactivity (16). However, more recent development of pharmacological and genetic tools to modulate 2-AG signaling combined with robust preclinical efforts has resulted in a surge of interest in advancement of 2-AG augmentation approaches, primarily via monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) inhibition (17, 18), for therapeutics development. Here we review the basic biology of 2-AG signaling, preclinical data supporting a role for 2-AG in stress adaptation and anxiety modulation, and the current state of MAGL inhibitor development. Dynamic determinants of potential drug efficacy and opportunities and potential challenges to the advancement of MAGL inhibitors are also discussed.

Biochemistry and physiology of 2-AG

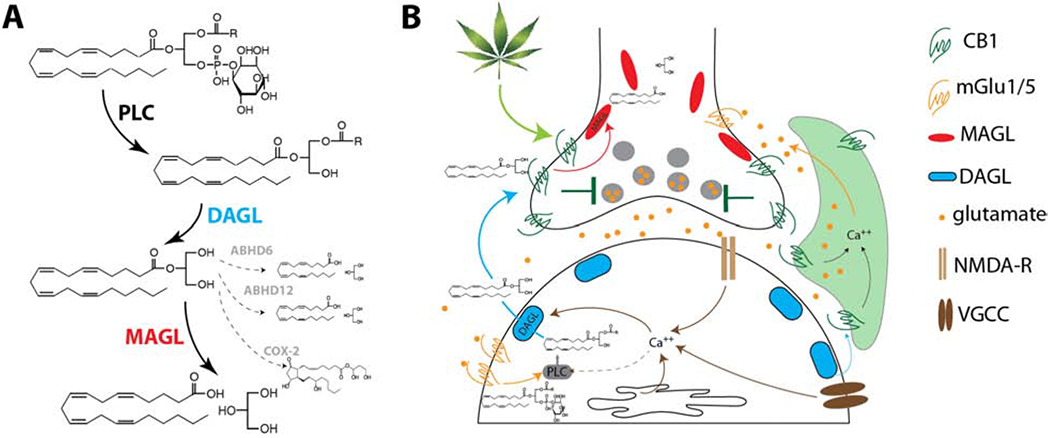

2-AG is a highly abundant neutral eicosanoid identified as an eCB ligand in 1995 (19, 20). The most well-established enzymatic pathway subserving brain 2-AG metabolism is shown in Figure 1A. 2-AG is synthesized primarily by diacylglycerol lipase alpha (DAGLα) in neurons from Sn-2 arachidonic acid-containing diacylglycerols, predominantly Sn1-stearoyl-Sn-2-arachidonoylglycerol (21, 22). 2-AG can also be synthesized by diacylglycerol lipase beta (DAGLβ) within non-neuronal cell-types (23). 2-AG is primarily hydrolyzed by MAGL (24), but can also be hydrolyzed by alpha-beta hydrolase domain-containing protein 6 and 12 (ABHD6 and ABHD12) (25) and oxygenated by cyclooxygenase-2 to generate prostaglandin-glycerols (26); however the contributions of these minor pathways to physiological regulation of 2-AG signaling remains unclear (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, mutations in ABHD12 are linked to the neurodegenerative disorder polyneuropathy, hearing loss, ataxia, retinosis pigmentosa, and cataract (PHARC), which is thought to be related to dysregulated lysophosphatidylserine metabolism (27, 28).

Figure 1. Biochemistry and Synaptic Physiology of 2-AG signaling.

(A) Schematic depiction of enzymatic synthesis and metabolism of 2-AG. Major routs shown with solid arrows, while minor or theoretical metabolic pathways and products shown in dashed arrows. (B) Schematic diagram of synaptic 2-AG signaling at a central glutamatergic synapse. 2-AG is released from post-synaptic neurons in response to calcium influx via multiple routs. Once released, 2-AG travels in retrograde manner to activate CB1 receptors on presynaptic axon terminals. Once active, CB1 signals to reduce the probability of neurotransmitter release, thus acting as a feedback mechanism limiting excess glutamate release. 2-AG can also act on astrocytic CB1 (green cell), or potentially mitochondrial CB1 (not shown), to indirectly regulate glutamate release via release of gliotransmitters including glutamate itself.

2-AG is a full agonist of cannabinoid receptors (CB1 and CB2) and functions as an eCB retrograde signaling molecule (29). Specifically, 2-AG mobilization in neurons occurs through at least three mechanisms; a purely calcium-dependent mechanism, a purely metabotropic Gq-protein-coupled receptor mechanism, and a combined calcium-assisted metabotropic mechanism (30) (Fig. 1B). Once synthesized, 2-AG is released and activates presynaptically located CB1 receptors to reduce neurotransmitter release probability. 2-AG activation of CB1 can result in short-term reversible synaptic depression in the forms of depolarization-induced suppression of excitation/inhibition (DSE/DSI), but also long-term irreversible synaptic depression (LTD) (30, 31). Recent studies have implicated 2-AG signaling in the tonic suppression of neurotransmitter release and in the indirect modulation of neurotransmitter release via activation of astrocytic CB1, which increases intracellular calcium and promotes glial glutamate release (32–34) (Fig. 1B). Importantly, MAGL inhibition can enhance phasic and tonic 2-AG-mediated signaling at central synapses (35–37). 2-AG also serves as a precursor for brain arachidonic acid and thus MAGL activity is a central regulator of free arachidonic acid levels (38), and consequently, prostaglandin signaling in the brain and some peripheral tissues (39). Lastly, MAGL also hydrolyzes several other monoacylglycerols in addition to 2-AG, many of which have unknown biological activity. Given the primary role of MAGL in regulating 2-AG levels and synaptic transmission, pharmacological approaches to augment 2-AG signaling for therapeutic gain has focused primarily on MAGL inhibition thus far.

2-AG signaling in the modulation of anxiety and stress adaptation

There is growing preclinical evidence that 2-AG signaling plays an important role in modulating stress adaptation and anxiety/depressive-like behaviors in rodents. Studies examining the effects of stress exposure on 2-AG levels have uncovered increases in 2-AG levels in the PFC and amygdala after acute and especially repeated homotypic stress exposure (40–44). The primary mechanism mediating 2-AG increases is likely the release of glucocorticoid hormones (45–50) as acute stress-induced increases in amygdala 2-AG positively correlate with the amygdala corticosterone levels (41). In contrast, some forms of chronic stress have been shown to reduce 2-AG levels and 2-AG levels show a delayed deficiency after some forms of stress (51–53). Overall, while acute or repeated homotypic stress may engage 2-AG signaling during stress exposure, 2-AG deficiency may be observed between exposures, and unpredictable forms of stress may more consistently produce 2-AG deficient states. These data highlight the complicated dynamic nature of 2-AG signaling over time as a function of stress-exposure.

Pharmacological and genetic studies suggest important functions of 2-AG signaling in reducing the expression of anxiety-like behaviors, promoting habituation and adaptation under the conditions of repeated stress exposures, and modulating susceptibility to the adverse behavioral consequences of acute stress. For example, genetic and pharmacological inhibition of 2-AG synthesis increases (22, 41, 54, 55), while pharmacological augmentation of 2-AG levels decrease, anxiety-like behavior in rodent models (Table 1). In addition, blockade or genetic deletion of CB1 receptors worsens the adverse behavioral consequences of chronic stress and impairs behavioral and neuroendocrine habituation to repeated stress (40, 44, 56–59), while 2-AG augmentation reduces anxiety- and depressive-like behaviors induced by acute and chronic stress exposure (Table 2). Lastly, genetic and pharmacological inhibition of 2-AG synthesis impairs conditioned fear extinction (55, 60) and promotes the susceptibility to develop anxiety-like behaviors after acute and repeated stress, while 2-AG augmentation promotes resilience to the adverse behavioral effects of stress (61–63). These studies provide compelling support for the notion that 2-AG can counteract some of the adverse behavioral effects of stress. They also suggest some forms of stress, or prolonged stress, can lead to 2-AG deficiency states which could contribute to the expression of stress-induced behavioral dysregulation. A corollary of these conclusions suggests pharmacological augmentation of 2-AG signaling could represent a novel approach to counteracting the deleterious consequences of stress.

Table 1.

Effects of MAGL inhibition on innate anxiety.

| Drug/dose | Mechanism | Test | Animals | Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JZL184 8,16, 40 mg/kg | CB1 mediated effects | Marble burying | C57BL/6j mice | ↓ marble burying | (66) |

| JZL184 16 mg/kg | CB1 mediated effects | Marble burying | CD-1 mice | ↓ marble burying | (76) |

| JZL184 8 mg/kg acute and chronic | CB1 mediated effects | EPM | SD rats | ↑ percentage open-arm time and number of open-arm entries | (67) |

| JZL184 8 mg/kg | CB2 mediated effects | EPM EZM |

Swiss albino, C57BL/6j mice | ↑ percent time in open-area and percent time in open-arms | (65) |

| JZL184 8 and 16 mg/kg | - | EPM OF |

CD-1 mice | ↓ percent time in closed-arm, ↑ percent time on central zone and locomotion in open-field test | (68) |

| JZL184 16 mg/kg | - | EPM | CD-1 mice | ↑ open-arm time and open-arm entries in EPM and CORT synthesis inhibitor blocked anxiolytic effects. | (69) |

| KML29 Intra BLA 200ng | CB1 mediated effects | EPM | SD rats | ↑ percent time in open-arm under low emotional arousal condition | (75) |

| JZL184 5, 10, 15 mg/kg | - | Light/dark box | CD-1 mice | ↑ percent light time and distance travelled in light-zone | (41) |

| JZL184 15 mg/kg | - | NIFS | CD-1 mice | ↓ feeding latency and ↑ consumption | (54) |

Abbreviations: EPM- elevated plus maze; EZM- elevated zero maze; OF- open field; NIFS- novelty induced feeding suppression

Table 2.

Effects of MAGL inhibition on stress-induced behaviors

| Drag/dose | Mechanism | Test | Animals | Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JZL184 16mg/kg 10 days | CB1 mediated effects | NIFS | CD-1 mice | Attenuated chronic restraint stress-induced increase in feeding latency | (76) |

| JZL184 Intra BNST 30 pmol | CB1 mediated effects | Blood pressure, Heart rate | Wistar rats | ↓ restraint-induced increase in heart rate | (130) |

| JZL184 16 mg/kg NF1819 Intra BLA 5 ng | CB1 mediated effects | EPM | SD rats | Inhibited TMT-induced reduction in percent open-arm time and open-arm entries; effects are mediated by BLA | (62) |

| JZL184 16 mg/kg Intra NAc 1 μg | - | EPM | C57BL/6j mice | Normalized social defeat-induced reductions in EPM scores and synaptic depression in NAc in socially defeated mice | (63) |

| JZL184 8 mg/kg | CB1 mediated effects | Light/dark box,NIFS | C57BL/6j mice | ↑ percent light distance traveled in LD and ↓ footshock-induced increase in feeding latency | (61) |

| JZL184 5, 10, 15 mg/kg | CB1 mediated effects | Light/dark box, NIFS and EZM | CD-1 mice | Attenuated restraint-induced decreases in percent light time and percent light distance | (41) |

| JZL184 10 mg/kg | CB1 mediated effects | Light/dark box, NIFS and EZM | CD-1 mice | Attenuated restraint-induced decreases in percent light time and percent light distance in LD Attenuated footshock-induced decreases in open-arm entries and total distance |

(54) |

| MJN110 10, 20 mg/kg JZL184 1, 3 mg/kg | - | EPM | Wistar rats C57BL/6j mice | Normalized alcohol abstinence-induced decrease in percent open-arm time | (73) |

| JZL184 16 mg/kg | - | Open field | Wistar rats | Attenuated TBI-induced decrease in center time Decreased TB-induced GR phosphorylation in CeA |

(74) |

| JZL184 8 mg/kg Chronic | CB1 mediated effects | NIFS FST SPT |

C57BL/6j | Prevented CUS-induced decrease in sucrose preference Prevented CUS-induced increase in feeding latency in NIFS and immobility time in FST Behavioral effects via enhancement of mTOR signaling |

(53) |

| JZL184 8 mg/kg Chronic | - | NIFS FST |

C57BL/6j | Prevented CUS-induced increase in feeding latency in NIFS and immobility time in FST Enhanced adult neurogenesis and long-term synaptic plasticity |

(70) |

| JZL184 5, 15mg/kg KLM29 10 mg/kg |

CB1 mediated effects | FST SPT |

CD-1 mice C57BL/6j | Prevented stress-induced increase in immobility time through glutamatergic LTD LTD induction requires CB1 in astroglial cells |

(71) |

| JZL184 8 mg/kg | CB1 mediated effects | NIFS | C57BL/6j mice | ↓ alcohol abstinence-induced increase in feeding latency | (72) |

| JZL184 0.1 and 1 mg/kg | - | Fear extinction | SD rats | Reduced freezing to trauma-associated context | (131) |

| JZL184 16 mg/kg | - | Fear conditioning | Wistar rats | ↓ freezing time during fear acquisition | (132) |

| MJN110 1 and 5 mg/kg | - | Social interaction | SD rats | ↓ aggressive behavior after post-weaning social isolation | (133) |

| JZL184 8 and 16 mg/kg | CB1 independent effects | Resident/intruder paradigm | CD-1 mice | ↓ aggressive behavior Effects are not blocked by AM251 | (134) |

Abbreviations: NIFS- novelty induced feeding suppression; EPM- elevated-plus maze; BLA- basolateral amygdala; NAc- nucleus accumbens; EZM- elevated-zero maze; OF- open-field; LD- Light/Dark Box test; TBI- traumatic brain injury; GR- glucocorticoid receptor; CeA- central amygdala; CUS- chronic unpredictable stress; FST- forced swim test; SPT- sucrose preference test

Efficacy of MAGL inhibition in preclinical models

Reduction in tension, stress-coping, and anxiolysis are among the most common reasons cited for continued cannabis use in chronic users (5, 64). These observations, combined with expanding understanding of the physiological functions of 2-AG signaling in the regulation of stress adaptation as described above, have led to the investigation of eCB augmentation strategies in preclinical models of anxiety-like behaviors. Numerous studies have recently demonstrated that acute systemic MAGL inhibition decreases anxiety-like behaviors under basal and high environmentally aversive conditions (41, 65–69) (Table 1). Systemic MAGL inhibition also reduces acute and chronic stress-induced anxiety-like and depressive-like behaviors (41, 53, 54, 62, 70, 71) (Table 2). Moreover, MAGL inhibition suppresses the anxiety-like and depressive-like behavior elicited by traumatic brain injury and alcohol abstinence (72–74). Taken together, these data provide substantial evidence that MAGL inhibition exerts anxiolytic and to a lesser extent antidepressant-like effects in validated rodent models.

Potential mechanisms of action of MAGL inhibition in the CNS

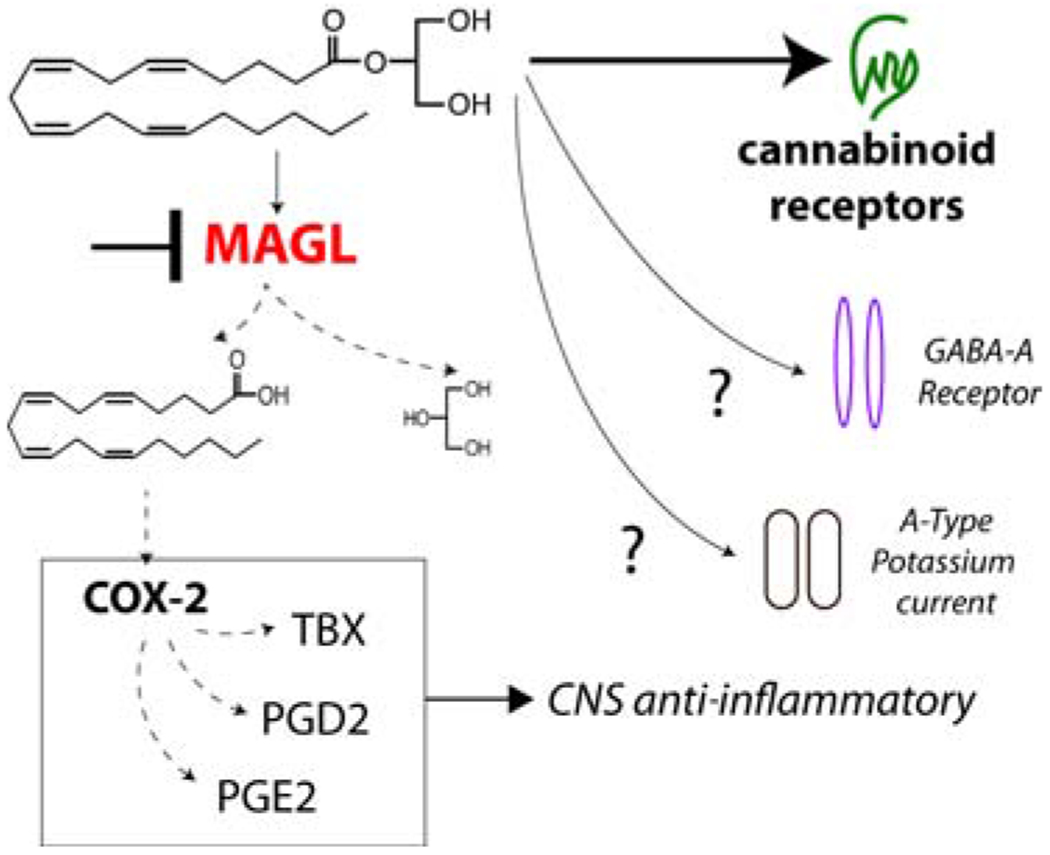

Despite the strong preclinical research base supporting the anxiolytic and stress-adaptive effects of MAGL inhibition, significantly less is known regarding the downstream molecular mechanisms mediating these effects. Figure 2 illustrates potential molecular mechanisms that could subserve therapeutic effects of MAGL inhibition. Canonically, MAGL inhibition elevates 2-AG levels and subsequent activity at cannabinoid receptors. Indeed, the anxiolytic effects of MAGL inhibition have been shown to be blocked by CB1 (41, 61, 68, 69, 75, 76), and to a lesser degree CB2 (65), antagonists. MAGL inhibition has also been shown to normalize stress-induced decreases in mTOR signaling, glucocorticoid receptor phosphorylation, neurogenesis and long-term synaptic plasticity (53, 70, 74). However, there are a number of other potential mechanisms by which MAGL inhibition could exert effects on brain function and behavior. For example, within the CNS, MAGL is a critical regulator of free arachidonic acid levels, and consequently prostaglandin synthesis (38, 39). Indeed, near complete MAGL inhibition reduces prostaglandin levels in the brain. These data suggest MAGL could exert anti-inflammatory effects in the CNS and/or reduce prostaglandin-mediated synaptic signaling, a process that could be amplified under neuroinflammatory conditions. Lastly, some studies have suggested other molecular targets by which 2-AG could regulate neuronal function including allosteric modulation of GABAa receptors (77) and inhibition of A-type potassium currents (78). The extents to which these non-canonical mechanisms contribute to the behavioral and physiological effects of MAGL inhibition remain to be experimentally determined.

Figure 2. Potential Mechanisms by Which MAGL Inhibition Exerts Pharmacological Effects.

MAGL inhibition (red) results in buildup of 2-AG (and other monoacylglycerols; not shown), which can activate CB1/2 cannabinoid receptors and potentially engage other receptor targets such as GABA-A receptors and potassium channels. Concomitantly, MAGL inhibition can reduce arachidonic acid levels and thereby reduce synthesis of prostaglandins via cyclooxygenase enzymes (i.e. COX-2). It is possible that this reduction in prostaglandin production after MAGL inhibition could exert anti-inflammatory effects and contribute the therapeutic profile of MAGL inhibitors under some conditions.

Endocannabinoid signaling dynamics in the consideration of MAGL inhibitor efficacy

Preclinical studies have identified potentially important factors related to the dynamic nature of eCB signaling that could affect the efficacy of 2-AG modulation approaches for the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. These include changes in CB1 receptor function/expression and 2-AG metabolism as a function of pathological state and drug administration. Understanding these dynamic changes associated with pathological conditions will be important for selection of clinical indications and patient populations when designing clinical efficacy trials of MAGL inhibitors.

The most well-established factor that could affect MAGL efficacy is the reduction in CB1 receptor signaling and/or expression observed after repeated or chronic stress exposure often used to model specific biobehavioral domains of affective disorders including avoidance behaviors and anhedonia. For example, repeated restraint stress and chronic unpredictable stress both reduce CB1 receptor density, expression, and CB1-mediated synaptic signaling in several brain regions including the striatum (79–82), hippocampus (51, 79, 83, 84), hypothalamus (49, 85) and amygdala (86). Similar effects have been observed after chronic stress and corticosterone treatment at the level of CB1 receptor binding in several brain regions (87). Interestingly, studies in the hypothalamus indicate that this effect is reversible with time (49) but also rapidly upon exposure to novel stressors after repeated homotypic stress exposure (85). These data suggest that after relatively short-lived homotypic stress exposure, synaptic CB1 receptor function may be impaired by reversible mechanisms such as receptor internalization; however, whether prolonged stress results in more persistent or less rapidly reversible CB1 loss-of-function is not known. Consistent with well-established concepts of agonist-induced receptor desensitization (88), repeated high-dose MAGL inhibitor treatment in rodents also results in a dose-dependent CB1 downregulation/desensitization in a heterogenous regional pattern (89), suggesting tolerance could be a limiting factor in advancement of MAGL inhibitors.

Taken together, these data raise several important questions. First, is stress-induced down-regulation of CB1 mediated via increased 2-AG release known to occur in response to homotypic stress exposure, or does it occur independently of elevations in 2-AG. Given that glucocorticoids have been shown to decrease CB1 receptor transcription (90), it is also possible that these effects are primarily driven by genomic actions of glucocorticoids. Second, is the reduced CB1 expression/signaling after stress exposure associated with reduced efficacy of MAGL inhibition-induced anxiolytic action, or does this downregulation provide an opportunity to increase CB1 function via MAGL inhibition in an attempt to normalize deficient eCB signaling. Relevantly, work by Zhang et al. and Sumislawski et al. has demonstrated chronic/repeated MAGL inhibition can reduce anxiety-like and depressive-like behaviors after chronic unpredictable, or repeated restraint, stress exposure (70, 76), paradigms previously associated with CB1 downregulation (49, 51, 86), supporting the latter hypothesis. However, replication and confirmation of these effects will be required before strong conclusions could be drawn on this issue.

Development of human CB1 PET ligands have also begun to elucidate differences in CB1 availability across a variety of relevant pathological conditions and behavioral states. Reversible CB1 receptor downregulation has been demonstrated in chronic cannabis users (91–93), consistent with the notion of CB1 agonist-induced receptor desensitization observed with high-dose MAGL inhibition (see above). Recent studies have also detected increased CB1 availability in healthy male relative to female volunteers, suggesting careful consideration of sex in clinical trials of eCB modulators is warranted (94). With regard to CB1 availability changes in patients with affective and trauma-related disorders, Neumeister and colleagues found reduced CB1 availability in all brain regions examined in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) relative to trauma exposed and healthy controls (95). Alterations in CB1 availability have also been documented in a variety of psychiatric conditions including alcohol use disorder, eating disorders, and schizophrenia [see (96)].

In addition to changes in CB1 receptor availability/signaling, 2-AG levels in the brain are also highly dynamic. As discussed above, acute and repeated stress produce transient increases in 2-AG levels in limbic brain regions, whereas a delayed deficiency state has also been observed, and chronic unpredictable stress has also been shown to reduce 2-AG levels. The recent development of DAGL inhibitors and DAGLα KO mice has further increased our knowledge of the role of 2-AG signaling in stress and anxiety-related behaviors. Specifically, pharmacological or genetic depletion of 2-AG increases anxiety- and depressive-like behaviors and impairs fear extinction (22, 41, 55, 60). In line with this, amygdala-specific DAGLα deletion (61) and overexpression of MAGL in hippocampus (97), both of which decreases 2-AG levels, produce anxiety-like states in mice. Blockade of 2AG/CB1 receptor signaling has been shown to prolong the neuroendocrine stress response and impair normal adaptation to the repeated stress exposure (40, 44, 45). These data suggest MAGL inhibitor efficacy would be maximal under conditions of 2-AG deficiency, thus elucidating specific pathological conditions under which central 2-AG deficiency occurs in humans represents a critical area for further research. Data examining this issue thus far have shown that peripheral 2-AG levels are reduced in the patients with major depression (98) and PTSD (99), however opposite results are also reported (100). Another study found that low circulating levels of 2-AG predict rates of depression after cardiac surgery (101), and a more recent study revealed that healthy volunteers exposed to chronic stressor of isolation and confinement exhibited reduced blood concentrations of 2-AG (102). Despite these data, the interpretability of peripheral 2-AG as a biomarker for central 2-AG-mediated eCB signaling is questionable based on recent mouse data demonstrating normal peripheral 2-AG levels in DAGLα KO mice, which have robustly reduced brain 2-AG levels (22). In this context, analysis of cerebrospinal fluid 2-AG, if detectable, may be more informative then peripheral measures. Lastly, changes in 2-AG levels associated with specific disorders of course do not imply causal roles for dysregulated 2-AG signaling in disease processes.

Current status of clinical MAGL inhibitor development

Pharmaceutical companies and academic institutions have reported ~22 patents describing development of potent MAGL inhibitors (https://patentscope.wipo.int/). A list of MAGL inhibitors and associated recent MAGL inhibitor patents is compiled in Table S1 and Table S2, respectively (and see (103)). Initially developed MAGL inhibitors had modest potency and lacked selectivity over FAAH (104–106). By using competitive activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) assays, Cravatt and colleagues discovered the irreversible, potent, and selective inhibitor JZL184, which exhibited good selectivity over FAAH without off-target effects at cannabinoid receptors or other catalytic serine-containing enzymes (107). JZL184 was a valuable tool used to confirm that MAGL is a primary degradation enzyme for 2-AG; however, JZL184 did show some cross-reactivity with FAAH at higher doses (40mg/kg) and showed some species differences in MAGL inhibition efficacy (107). To further optimize selectivity, Cravatt and colleagues developed KLM29 and MJN110, which displayed in vivo activity in several pain models without showing cross-reactivity with FAAH or cannabimimetic side effects (108).

To support the clinical investigation of 2-AG modulation, Abide Therapeutics (recently purchased by H. Lundbeck A/S) developed and tested an advanced irreversible MAGL inhibitor ABD-1970. ABD-1970 blocked 2-AG hydrolysis in human tissue by 95% (109). Similarly, ex vivo ABD-1970 treatment inhibited MAGL in blood cells and elevated 2-AG levels in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human whole blood. The concentration dependent inhibition of MAGL in peripheral blood mononuclear cells provided a valuable biomarker to measure peripheral target engagement in human subjects (109). Recently, the same company has developed a highly potent, selective and orally available CNS-penetrant MAGL inhibitor, ABX-1431, with excellent drug-like properties suitable for once-per-day oral administrations (18). ABX-1431 is a potent human MAGL inhibitor with an average IC50 of 14 nM and only shows off target activity against ABHD6 (>100-fold selectivity), PLA2G7 (>200-fold selectivity) and some carboxyesterases (18). ABX-1431 was shown to be well-tolerated and safe in a single-dose phase 1 clinical study. An exploratory phase 1b study suggests MAGL inhibition may have the potential to treat symptoms of Tourette syndrome in adult patients (110). Advanced clinical trials with this drug are expected in the coming years.

Most recently, Aida et al. described the first potent, selective, and in vivo bioactive reversible MAGL inhibitor, R-3t (111). R-3t was able to increase brain 2-AG levels after oral administration, providing the first evidence that reversible MAGL inhibition can result in elevations of brain 2-AG. Reversible enzymatic inhibition could confer pharmacokinetic advantages over irreversible inhibition, and thus these findings represent a significant advance in the field of MAGL drug development. Future clinical studies will be required to determine whether reversible MAGL inhibition provides a substantial advantage with regard to safety, tolerability, or efficacy, relative to drugs with irreversible modes of enzymatic inhibition.

Potential adverse effects of MAGL inhibitors

The recent clinical studies using ABX-1431 showed that it is well-tolerated and safe in humans. The most common reported side effects are headache, somnolence, and fatigue (17). In this section, we discuss possible adverse effects of chronic MAGL inhibition that might not have been apparent in early phase clinical studies. In theory, it is possible that chronic MAGL inhibition could cause typical cannabimimetic effects including cognitive and coordination impairment, and sedation (112). However, a number of preclinical studies have demonstrated efficacy of MAGL inhibitors without overt cannabimimetic side effects (54, 65, 113, 114). Relevant to potential use of MAGL inhibitors in stress-related and affective disorders, some studies have demonstrated increases in anxiety/fear-related behaviors (115, 116), while amygdala-specific 2-AG synthesis inhibition was shown to decrease anxiety-like behavior after acute stress in rats (47), suggesting acute increases in fear and anxiety-related behaviors may also be present after MAGL inhibition. In this context, it has been suggested that CB1 receptors expressed on distinct GABAergic versus glutamatergic nerve terminals may contribute to the anxiogenic versus anxiolytic actions of eCBs, respectively (116, 117). The conditions under which these seemingly paradoxical effects would be manifested remains unclear. MAGL inhibition has also been shown to enhance dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens and elicits premature reward seeking (118), suggesting the possibility of abuse/dependence liability. In this context however, MAGL inhibitors do not substitute for THC in drug discrimination assays (113) (but CB1 receptor can mediate MAGL inhibitor discriminative stimulus (119)), raising the intriguing possibility that MAGL inhibitors may have relatively lower abuse liability then cannabis products or THC. Lastly, dose titration will likely be a critical parameter in subsequent clinical trials as preclinical data clearly demonstrated desensitization of CB1 receptors at near complete levels of MAGL inhibition (see above). As clinical trials with MAGL inhibitors are in their infancy, careful analysis of adverse effects after long-term MAGL inhibition will be of significant interest to the scientific and clinical community.

Advancing MAGL inhibitors for the treatment of anxiety and stress-related disorders

The development of CNS drugs is an extremely challenging process that has seen considerable divestment in recent years (120). Some reasons for the failure of CNS drugs in clinical studies include inadequate target engagement, poor pharmacological activity, and lack of translation of preclinical efficacy (120, 121). Non-invasive imaging of MAGL via PET will likely play a crucial role in the evaluation of promising drug candidates targeting MAGL. PET neuroimaging could be used to directly measure tissue exposure and target engagement and help build pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) models (121). PET imaging of MAGL will allow for a deeper understanding of the dynamic nature of MAGL under pathological conditions, which is currently not well understood. In this context, several reversible and irreversible MAGL-targeted PET tracers are now available for in vivo studies (122–126). Additionally, peripheral and central biomarkers of target engagement and pharmacological effect (i.e. increases in 2-AG and related monoacylglycerols) will be critical to advancement of clinical candidates. Although, we have previously shown that peripheral 2-AG levels are positively correlated with the brain 2-AG levels after MAGL inhibition in mice (41), whether this effect or relationship is present or detectable in humans is not known. Alternatively, measures of cerebral spinal fluid 2-AG and related lipids will be required to build PK-PD relationships between MAGL occupancy and 2-AG elevation, or other surrogate behavioral or physiological biomarkers.

Several behavioral and neuroimaging-based biomarkers appear to be ideally suited to be used as intermediate endpoints in the development of MAGL inhibitors for the treatment of affective and stressor-related disorders. For example, it has recently been demonstrated that inhibition of FAAH in humans can attenuate autonomic, subjective self-report and affective-related facial muscle changes in response to acute stress challenge (16). Additionally, inhibition of FAAH was also found to enhance fear extinction by increasing extinction recall and reducing fear expression in healthy humans (16). These findings are consistent with preclinical rodent reports that elevating eCB signaling can dampen aspects of stress and fear and suggest that these outcome measures may act as endpoints which can provide proof-of-concept data as to whether inhibiting MAGL could have similar effects to FAAH inhibition and thus possess potential utility as an agent to treat stress- and anxiety-related psychiatric disorders.

Patient selection for early phase clinical studies for psychiatric disorders can be critical to a successful trial. Based on the preclinical and clinical data reviewed above, several theoretical opportunities exist to optimize patient selection for MAGL inhibitor trials. First, as several studies have found reduced levels of 2-AG in some patients afflicted with mood, anxiety or trauma-related disorders, measurements of basal 2-AG levels or elevated MAGL activity/binding may help to determine if someone has lower than average levels of 2-AG and thus may benefit more greatly from MAGL inhibition. Second, given the evidence that elevating 2-AG signaling can dampen excitatory drive to the amygdala (33, 61), neuroimaging studies of threat-related amygdala reactivity/habituation and ventromedial-prefrontal cortex-amygdala coupling (127–129) may also be a screening tool that could help to select subjects who may particularly benefit from MAGL inhibition. Elevated levels of baseline arousal and hyperactivity of the amygdala could indicate a phenotype that elevating 2-AG signaling may provide significant benefit to. Third, given the consistent reports of cannabinoids in reducing sleep-related disturbances associated with trauma-related disorders, such as PTSD (7), selection of patients with disruptions in sleep architecture, sleep-fragmentation or prominent nightmares could increase the likelihood of detecting positive symptom domain-specific signals in clinical trials.

Summary and conclusion

Data reviewed here indicate a prominent role for 2-AG signaling in the regulation of anxiety and stress adaptation and reveal considerable preclinical support for the advancement of MAGL inhibitors for treatment of anxiety, trauma-related and other affective disorders. Early phase clinical trials indicate acute MAGL inhibition is generally well-tolerated in humans, however the effects of chronic MAGL inhibition in humans are not known. We review a number of dynamic variables including CB1 expression and endogenous 2-AG levels, which could in theory influence the efficacy of MAGL inhibition for the treatment of anxiety disorders, and describe behavioral and neuroimaging-based biomarker approaches that could be used as outcomes in proof-of-concept studies in this regard. While there is substantial optimism that MAGL inhibitors could represent a novel class of anxiolytics, non-opioid analgesics, or antiepileptics, the efficacy of MAGL inhibition remains to be determined in clinical trials. Similarly, the long-term consequences of MAGL inhibition at optimized dosing including tolerance, abuse liability, and adverse effects remain to be determined.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors were supported by NIH grants MH107435 and AA026186 (S.P.) and funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (M.N.H). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures

SP is a paid consultant for Psy Therapeutics, H. Lundbeck A/S, and Sophren Therapeutics, and has received research contract support from H. Lundbeck A/S within the past 3 years. MNH is a paid consultant for Sophren Therapeutics. GB reports no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ren M, Tang Z, Wu X, Spengler R, Jiang H, Yang Y, et al. (2019): The origins of cannabis smoking: Chemical residue evidence from the first millennium BCE in the Pamirs. Sci Adv. 5:eaaw1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Betthauser K, Pilz J, Vollmer LE (2015): Use and effects of cannabinoids in military veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 72:1279–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonn-Miller MO, Vujanovic AA, Feldner MT, Bernstein A, Zvolensky MJ (2007): Posttraumatic stress symptom severity predicts marijuana use coping motives among traumatic event-exposed marijuana users. J Trauma Stress. 20:577–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keyhani S, Steigerwald S, Ishida J, Vali M, Cerda M, Hasin D, et al. (2018): Risks and Benefits of Marijuana Use: A National Survey of U.S. Adults. Ann Intern Med. 169:282–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dworkin ER, Kaysen D, Bedard-Gilligan M, Rhew IC, Lee CM (2017): Daily-level associations between PTSD and cannabis use among young sexual minority women. Addict Behav. 74:118–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lisboa SF, Gomes FV, Terzian AL, Aguiar DC, Moreira FA, Resstel LB, et al. (2017): The Endocannabinoid System and Anxiety. Vitam Horm. 103:193–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hill MN, Campolongo P, Yehuda R, Patel S (2018): Integrating Endocannabinoid Signaling and Cannabinoids into the Biology and Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 43:80–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lutz B, Marsicano G, Maldonado R, Hillard CJ (2015): The endocannabinoid system in guarding against fear, anxiety and stress. Nat Rev Neurosci. 16:705–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel S, Hill MN, Cheer JF, Wotjak CT, Holmes A (2017): The endocannabinoid system as a target for novel anxiolytic drugs. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 76:56–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunduz-Cinar O, Hill MN, McEwen BS, Holmes A (2013): Amygdala FAAH and anandamide: mediating protection and recovery from stress. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 34:637–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu SS, Mackie K (2015): Distribution of the Endocannabinoid System in the Central Nervous System. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 231:59–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Micale V, Drago F (2018): Endocannabinoid system, stress and HPA axis. Eur J Pharmacol. 834:230–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kathuria S, Gaetani S, Fegley D, Valino F, Duranti A, Tontini A, et al. (2003): Modulation of anxiety through blockade of anandamide hydrolysis. Nat Med. 9:76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huggins JP, Smart TS, Langman S, Taylor L, Young T (2012): An efficient randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial with the irreversible fatty acid amide hydrolase-1 inhibitor PF-04457845, which modulates endocannabinoids but fails to induce effective analgesia in patients with pain due to osteoarthritis of the knee. Pain. 153:1837–1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D'Souza DC, Cortes-Briones J, Creatura G, Bluez G, Thurnauer H, Deaso E, et al. (2019): Efficacy and safety of a fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitor (PF-04457845) in the treatment of cannabis withdrawal and dependence in men: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group, phase 2a single-site randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 6:35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayo LMAA, Linde J, Morena M, Haataja R, Hammar V, Augier G, Hill MN, Heilig M (2019): Elevated anandamide, enhanced recall of fear extinction, and attenuated stress responses following inhibition of fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH): a randomized, controlled experimental medicine trial. Biological psychiatry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang M, van der Stelt M (2018): Activity-Based Protein Profiling Delivers Selective Drug Candidate ABX-1431, a Monoacylglycerol Lipase Inhibitor, To Control Lipid Metabolism in Neurological Disorders. J Med Chem. 61:9059–9061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cisar JS, Weber OD, Clapper JR, Blankman JL, Henry CL, Simon GM, et al. (2018): Identification of ABX-1431, a Selective Inhibitor of Monoacylglycerol Lipase and Clinical Candidate for Treatment of Neurological Disorders. J Med Chem. 61:9062–9084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mechoulam R, Ben-Shabat S, Hanus L, Ligumsky M, Kaminski NE, Schatz AR, et al. (1995): Identification of an endogenous 2-monoglyceride, present in canine gut, that binds to cannabinoid receptors. Biochemical pharmacology. 50:83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sugiura T, Kondo S, Sukagawa A, Nakane S, Shinoda A, Itoh K, et al. (1995): 2-Arachidonoylglycerol: a possible endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligand in brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 215:89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jung KM, Astarita G, Zhu C, Wallace M, Mackie K, Piomelli D (2007): A key role for diacylglycerol lipase-alpha in metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent endocannabinoid mobilization. Molecular pharmacology. 72:612–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shonesy BC, Bluett RJ, Ramikie TS, Baldi R, Hermanson DJ, Kingsley PJ, et al. (2014): Genetic disruption of 2-arachidonoylglycerol synthesis reveals a key role for endocannabinoid signaling in anxiety modulation. Cell reports. 9:1644–1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao Y, Vasilyev DV, Goncalves MB, Howell FV, Hobbs C, Reisenberg M, et al. (2010): Loss of retrograde endocannabinoid signaling and reduced adult neurogenesis in diacylglycerol lipase knock-out mice. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 30:2017–2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blankman JL, Simon GM, Cravatt BF (2007): A comprehensive profile of brain enzymes that hydrolyze the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol. Chemistry & biology. 14:1347–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Savinainen JR, Saario SM, Laitinen JT (2012): The serine hydrolases MAGL, ABHD6 and ABHD12 as guardians of 2-arachidonoylglycerol signalling through cannabinoid receptors. Acta physiologica (Oxford, England). 204:267–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morgan AJ, Kingsley PJ, Mitchener MM, Altemus M, Patrick TA, Gaulden AD, et al. (2018): Detection of Cyclooxygenase-2-Derived Oxygenation Products of the Endogenous Cannabinoid 2-Arachidonoylglycerol in Mouse Brain. ACS Chem Neurosci. 9:1552–1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blankman JL, Long JZ, Trauger SA, Siuzdak G, Cravatt BF (2013): ABHD12 controls brain lysophosphatidylserine pathways that are deregulated in a murine model of the neurodegenerative disease PHARC. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110:1500–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fiskerstrand T, H’Mida-Ben Brahim D, Johansson S, M’Zahem A, Haukanes BI, Drouot N, et al. (2010): Mutations in ABHD12 cause the neurodegenerative disease PHARC: An inborn error of endocannabinoid metabolism. Am J Hum Genet. 87:410–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katona I, Freund TF (2012): Multiple functions of endocannabinoid signaling in the brain. Annual review of neuroscience. 35:529–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohno-Shosaku T, Kano M (2014): Endocannabinoid-mediated retrograde modulation of synaptic transmission. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 29:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castillo PE, Younts TJ, Chavez AE, Hashimotodani Y (2012): Endocannabinoid signaling and synaptic function. Neuron. 76:70–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Navarrete M, Araque A (2008): Endocannabinoids mediate neuron-astrocyte communication. Neuron. 57:883–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramikie TS, Nyilas R, Bluett RJ, Gamble-George JC, Hartley ND, Mackie K, et al. (2014): Multiple mechanistically distinct modes of endocannabinoid mobilization at central amygdala glutamatergic synapses. Neuron. 81:1111–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Navarrete M, Diez A, Araque A (2014): Astrocytes in endocannabinoid signalling. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 369:20130599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Makara JK, Mor M, Fegley D, Szabo SI, Kathuria S, Astarita G, et al. (2005): Selective inhibition of 2-AG hydrolysis enhances endocannabinoid signaling in hippocampus. Nature neuroscience. 8:1139–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pan B, Wang W, Long JZ, Sun D, Hillard CJ, Cravatt BF, et al. (2009): Blockade of 2-arachidonoylglycerol hydrolysis by selective monoacylglycerol lipase inhibitor 4-nitrophenyl 4-(dibenzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl(hydroxy)methyl)piperidine-1-carboxylate (JZL184) Enhances retrograde endocannabinoid signaling. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 331:591–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Straiker A, Wager-Miller J, Hu SS, Blankman JL, Cravatt BF, Mackie K (2011): COX-2 and fatty acid amide hydrolase can regulate the time course of depolarization-induced suppression of excitation. British journal of pharmacology. 164:1672–1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Long JZ, Nomura DK, Cravatt BF (2009): Characterization of monoacylglycerol lipase inhibition reveals differences in central and peripheral endocannabinoid metabolism. Chemistry & biology. 16:744–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nomura DK, Morrison BE, Blankman JL, Long JZ, Kinsey SG, Marcondes MC, et al. (2011): Endocannabinoid hydrolysis generates brain prostaglandins that promote neuroinflammation. Science. 334:809–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hill MN, McLaughlin RJ, Bingham B, Shrestha L, Lee TT, Gray JM, et al. (2010): Endogenous cannabinoid signaling is essential for stress adaptation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107:9406–9411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bedse G, Hartley ND, Neale E, Gaulden AD, Patrick TA, Kingsley PJ, et al. (2017): Functional Redundancy Between Canonical Endocannabinoid Signaling Systems in the Modulation of Anxiety. Biological psychiatry. 82:488–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bluett RJ, Gamble-George JC, Hermanson DJ, Hartley ND, Marnett LJ, Patel S (2014): Central anandamide deficiency predicts stress-induced anxiety: behavioral reversal through endocannabinoid augmentation. Translational psychiatry. 4:e408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hill MN, McLaughlin RJ, Morrish AC, Viau V, Floresco SB, Hillard CJ, et al. (2009): Suppression of amygdalar endocannabinoid signaling by stress contributes to activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 34:2733–2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patel S, Roelke CT, Rademacher DJ, Hillard CJ (2005): Inhibition of restraint stress-induced neural and behavioural activation by endogenous cannabinoid signalling. Eur J Neurosci. 21:1057–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hill MN, McLaughlin RJ, Pan B, Fitzgerald ML, Roberts CJ, Lee TT, et al. (2011): Recruitment of prefrontal cortical endocannabinoid signaling by glucocorticoids contributes to termination of the stress response. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 31:10506–10515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Balsevich G, Petrie GN, Hill MN (2017): Endocannabinoids: Effectors of glucocorticoid signaling. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology. 47:86–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Di S, Itoga CA, Fisher MO, Solomonow J, Roltsch EA, Gilpin NW, et al. (2016): Acute Stress Suppresses Synaptic Inhibition and Increases Anxiety via Endocannabinoid Release in the Basolateral Amygdala. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 36:8461–8470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Di S, Malcher-Lopes R, Marcheselli VL, Bazan NG, Tasker JG (2005): Rapid glucocorticoid-mediated endocannabinoid release and opposing regulation of glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid inputs to hypothalamic magnocellular neurons. Endocrinology. 146:4292–4301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wamsteeker JI, Kuzmiski JB, Bains JS (2010): Repeated stress impairs endocannabinoid signaling in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 30:11188–11196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang M, Hill MN, Zhang L, Gorzalka BB, Hillard CJ, Alger BE (2012): Acute restraint stress enhances hippocampal endocannabinoid function via glucocorticoid receptor activation. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England). 26:56–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hill MN, Patel S, Carrier EJ, Rademacher DJ, Ormerod BK, Hillard CJ, et al. (2005): Downregulation of endocannabinoid signaling in the hippocampus following chronic unpredictable stress. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 30:508–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Qin Z, Zhou X, Pandey NR, Vecchiarelli HA, Stewart CA, Zhang X, et al. (2015): Chronic stress induces anxiety via an amygdalar intracellular cascade that impairs endocannabinoid signaling. Neuron. 85:1319–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhong P, Wang W, Pan B, Liu X, Zhang Z, Long JZ, et al. (2014): Monoacylglycerol lipase inhibition blocks chronic stress-induced depressive-like behaviors via activation of mTOR signaling. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 39:1763–1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bedse G, Bluett RJ, Patrick TA, Romness NK, Gaulden AD, Kingsley PJ, et al. (2018): Therapeutic endocannabinoid augmentation for mood and anxiety disorders: comparative profiling of FAAH, MAGL and dual inhibitors. Translational psychiatry. 8:92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jenniches I, Ternes S, Albayram O, Otte DM, Bach K, Bindila L, et al. (2016): Anxiety, Stress, and Fear Response in Mice With Reduced Endocannabinoid Levels. Biological psychiatry. 79:858–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Litvin Y, Phan A, Hill MN, Pfaff DW, McEwen BS (2013): CB1 receptor signaling regulates social anxiety and memory. Genes Brain Behav. 12:479–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rabasa C, Pastor-Ciurana J, Delgado-Morales R, Gomez-Roman A, Carrasco J, Gagliano H, et al. (2015): Evidence against a critical role of CB1 receptors in adaptation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and other consequences of daily repeated stress. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 25:1248–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hill MN, Hillard CJ, McEwen BS (2011): Alterations in corticolimbic dendritic morphology and emotional behavior in cannabinoid CB1 receptor-deficient mice parallel the effects of chronic stress. Cereb Cortex. 21:2056–2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beyer CE, Dwyer JM, Piesla MJ, Platt BJ, Shen R, Rahman Z, et al. (2010): Depression like phenotype following chronic CB1 receptor antagonism. Neurobiol Dis. 39:148–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cavener VS, Gaulden A, Pennipede D, Jagasia P, Uddin J, Marnett LJ, et al. (2018): Inhibition of Diacylglycerol Lipase Impairs Fear Extinction in Mice. Front Neurosci. 12:479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bluett RJ, Baldi R, Haymer A, Gaulden AD, Hartley ND, Parrish WP, et al. (2017): Endocannabinoid signalling modulates susceptibility to traumatic stress exposure. Nature communications. 8:14782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lim J, Igarashi M, Jung KM, Butini S, Campiani G, Piomelli D (2016): Endocannabinoid Modulation of Predator Stress-Induced Long-Term Anxiety in Rats. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 41:1329–1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bosch-Bouju C, Larrieu T, Linders L, Manzoni OJ, Laye S (2016): Endocannabinoid-Mediated Plasticity in Nucleus Accumbens Controls Vulnerability to Anxiety after Social Defeat Stress. Cell reports. 16:1237–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gentes EL, Schry AR, Hicks TA, Clancy CP, Collie CF, Kirby AC, et al. (2016): Prevalence and correlates of cannabis use in an outpatient VA posttraumatic stress disorder clinic. Psychol Addict Behav. 30:415–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Busquets-Garcia A, Puighermanal E, Pastor A, de la Torre R, Maldonado R, Ozaita A (2011): Differential role of anandamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol in memory and anxiety-like responses. Biological psychiatry. 70:479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kinsey SG, O’Neal ST, Long JZ, Cravatt BF, Lichtman AH (2011): Inhibition of endocannabinoid catabolic enzymes elicits anxiolytic-like effects in the marble burying assay. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 98:21–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sciolino NR, Zhou W, Hohmann AG (2011): Enhancement of endocannabinoid signaling with JZL184, an inhibitor of the 2-arachidonoylglycerol hydrolyzing enzyme monoacylglycerol lipase, produces anxiolytic effects under conditions of high environmental aversiveness in rats. Pharmacological research. 64:226–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Aliczki M, Balogh Z, Tulogdi A, Haller J (2012): The temporal dynamics of the effects of monoacylglycerol lipase blockade on locomotion, anxiety, and body temperature. Behavioural pharmacology. 23:348–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Aliczki M, Zelena D, Mikics E, Varga ZK, Pinter O, Bakos NV, et al. (2013): Monoacylglycerol lipase inhibition-induced changes in plasma corticosterone levels, anxiety and locomotor activity in male CD1 mice. Hormones and behavior. 63:752–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang Z, Wang W, Zhong P, Liu SJ, Long JZ, Zhao L, et al. (2015): Blockade of 2-arachidonoylglycerol hydrolysis produces antidepressant-like effects and enhances adult hippocampal neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity. Hippocampus. 25:16–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang Y, Gu N, Duan T, Kesner P, Blaskovits F, Liu J, et al. (2017): Monoacylglycerol lipase inhibitors produce pro- or antidepressant responses via hippocampal CA1 GABAergic synapses. Molecular psychiatry. 22:215–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Holleran KM, Wilson HH, Fetterly TL, Bluett RJ, Centanni SW, Gilfarb RA, et al. (2016): Ketamine and MAG Lipase Inhibitor-Dependent Reversal of Evolving Depressive-Like Behavior During Forced Abstinence From Alcohol Drinking. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 41:2062–2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Serrano A, Pavon FJ, Buczynski MW, Schlosburg J, Natividad LA, Polis IY, et al. (2018): Deficient endocannabinoid signaling in the central amygdala contributes to alcohol dependence-related anxiety-like behavior and excessive alcohol intake. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 43:1840–1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fucich EA, Mayeux JP, McGinn MA, Gilpin NW, Edwards S, Molina PE (2019): A Novel Role for the Endocannabinoid System in Ameliorating Motivation for Alcohol Drinking and Negative Behavioral Affect after Traumatic Brain Injury in Rats. Journal of neurotrauma. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Morena M, Leitl KD, Vecchiarelli HA, Gray JM, Campolongo P, Hill MN (2016): Emotional arousal state influences the ability of amygdalar endocannabinoid signaling to modulate anxiety. Neuropharmacology. 111:59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sumislawski JJ, Ramikie TS, Patel S (2011): Reversible gating of endocannabinoid plasticity in the amygdala by chronic stress: a potential role for monoacylglycerol lipase inhibition in the prevention of stress-induced behavioral adaptation. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 36:2750–2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bakas T, van Nieuwenhuijzen PS, Devenish SO, McGregor IS, Arnold JC, Chebib M (2017): The direct actions of cannabidiol and 2-arachidonoyl glycerol at GABAA receptors. Pharmacological research. 119:358–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gantz SC, Bean BP (2017): Cell-Autonomous Excitation of Midbrain Dopamine Neurons by Endocannabinoid-Dependent Lipid Signaling. Neuron. 93:1375–1387 e1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hill MN, Carrier EJ, McLaughlin RJ, Morrish AC, Meier SE, Hillard CJ, et al. (2008): Regional alterations in the endocannabinoid system in an animal model of depression: effects of concurrent antidepressant treatment. J Neurochem. 106:2322–2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rossi S, De Chiara V, Musella A, Kusayanagi H, Mataluni G, Bernardi G, et al. (2008): Chronic psychoemotional stress impairs cannabinoid-receptor-mediated control of GABA transmission in the striatum. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 28:7284–7292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rossi S, De Chiara V, Musella A, Sacchetti L, Cantarella C, Castelli M, et al. (2010): Preservation of striatal cannabinoid CB1 receptor function correlates with the antianxiety effects of fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibition. Molecular pharmacology. 78:260–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang W, Sun D, Pan B, Roberts CJ, Sun X, Hillard CJ, et al. (2010): Deficiency in endocannabinoid signaling in the nucleus accumbens induced by chronic unpredictable stress. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 35:2249–2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Reich CG, Taylor ME, McCarthy MM (2009): Differential effects of chronic unpredictable stress on hippocampal CB1 receptors in male and female rats. Behav Brain Res. 203:264–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee TT, Hill MN (2013): Age of stress exposure modulates the immediate and sustained effects of repeated stress on corticolimbic cannabinoid CB(1) receptor binding in male rats. Neuroscience. 249:106–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wamsteeker Cusulin JI, Senst L, Teskey GC, Bains JS (2014): Experience salience gates endocannabinoid signaling at hypothalamic synapses. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 34:6177–6181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Patel S, Kingsley PJ, Mackie K, Marnett LJ, Winder DG (2009): Repeated homotypic stress elevates 2-arachidonoylglycerol levels and enhances short-term endocannabinoid signaling at inhibitory synapses in basolateral amygdala. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 34:2699–2709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bowles NP, Hill MN, Bhagat SM, Karatsoreos IN, Hillard CJ, McEwen BS (2012): Chronic, noninvasive glucocorticoid administration suppresses limbic endocannabinoid signaling in mice. Neuroscience. 204:83–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rajagopal S, Shenoy SK (2018): GPCR desensitization: Acute and prolonged phases. Cell Signal. 41:9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schlosburg JE, Blankman JL, Long JZ, Nomura DK, Pan B, Kinsey SG, et al. (2010): Chronic monoacylglycerol lipase blockade causes functional antagonism of the endocannabinoid system. Nature neuroscience. 13:1113–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mailleux P, Vanderhaeghen JJ (1993): Glucocorticoid regulation of cannabinoid receptor messenger RNA levels in the rat caudate-putamen. An in situ hybridization study. Neurosci Lett. 156:51–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.D’Souza DC, Cortes-Briones JA, Ranganathan M, Thurnauer H, Creatura G, Surti T, et al. (2016): Rapid Changes in Cannabinoid 1 Receptor Availability in Cannabis-Dependent Male Subjects After Abstinence From Cannabis. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 1:60–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ceccarini J, Kuepper R, Kemels D, van Os J, Henquet C, Van Laere K (2015): [18F]MK-9470 PET measurement of cannabinoid CB1 receptor availability in chronic cannabis users. Addict Biol. 20:357–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hirvonen J, Goodwin RS, Li CT, Terry GE, Zoghbi SS, Morse C, et al. (2012): Reversible and regionally selective downregulation of brain cannabinoid CB1 receptors in chronic daily cannabis smokers. Molecular psychiatry. 17:642–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Laurikainen H, Tuominen L, Tikka M, Merisaari H, Armio RL, Sormunen E, et al. (2019): Sex difference in brain CB1 receptor availability in man. NeuroImage. 184:834–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Neumeister A, Normandin MD, Pietrzak RH, Piomelli D, Zheng MQ, Gujarro-Anton A, et al. (2013): Elevated brain cannabinoid CB1 receptor availability in post-traumatic stress disorder: a positron emission tomography study. Molecular psychiatry. 18:1034–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sloan ME, Grant CW, Gowin JL, Ramchandani VA, Le Foll B (2019): Endocannabinoid signaling in psychiatric disorders: a review of positron emission tomography studies. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 40:342–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Guggenhuber S, Romo-Parra H, Bindila L, Leschik J, Lomazzo E, Remmers F, et al. (2015): Impaired 2-AG Signaling in Hippocampal Glutamatergic Neurons: Aggravation of Anxiety-Like Behavior and Unaltered Seizure Susceptibility. The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology. 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hill MN, Miller GE, Carrier EJ, Gorzalka BB, Hillard CJ (2009): Circulating endocannabinoids and N-acyl ethanolamines are differentially regulated in major depression and following exposure to social stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 34:1257–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hill MN, Bierer LM, Makotkine I, Golier JA, Galea S, McEwen BS, et al. (2013): Reductions in circulating endocannabinoid levels in individuals with post-traumatic stress disorder following exposure to the World Trade Center attacks. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 38:2952–2961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hauer D, Schelling G, Gola H, Campolongo P, Morath J, Roozendaal B, et al. (2013): Plasma concentrations of endocannabinoids and related primary fatty acid amides in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder. PloSone. 8:e62741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hauer D, Weis F, Campolongo P, Schopp M, Beiras-Fernandez A, Strewe C, et al. (2012): Glucocorticoid-endocannabinoid interaction in cardiac surgical patients: relationship to early cognitive dysfunction and late depression. Rev Neurosci. 23:681–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yi B, Nichiporuk I, Nicolas M, Schneider S, Feuerecker M, Vassilieva G, et al. (2016): Reductions in circulating endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol levels in healthy human subjects exposed to chronic stressors. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry. 67:92–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Granchi C, Caligiuri I, Minutolo F, Rizzolio F, Tuccinardi T (2017): A patent review of Monoacylglycerol Lipase (MAGL) inhibitors (2013–2017). Expert Opin Ther Pat. 27:1341–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hohmann AG, Suplita RL, Bolton NM, Neely MH, Fegley D, Mangieri R, et al. (2005): An endocannabinoid mechanism for stress-induced analgesia. Nature. 435:1108–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bisogno T, Ortar G, Petrosino S, Morera E, Palazzo E, Nalli M, et al. (2009): Development of a potent inhibitor of 2-arachidonoylglycerol hydrolysis with antinociceptive activity in vivo. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1791:53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.King AR, Dotsey EY, Lodola A, Jung KM, Ghomian A, Qiu Y, et al. (2009): Discovery of potent and reversible monoacylglycerol lipase inhibitors. Chemistry & biology. 16:1045–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Long JZ, Li W, Booker L, Burston JJ, Kinsey SG, Schlosburg JE, et al. (2009): Selective blockade of 2-arachidonoylglycerol hydrolysis produces cannabinoid behavioral effects. Nature chemical biology. 5:37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gil-Ordonez A, Martin-Fontecha M, Ortega-Gutierrez S, Lopez-Rodriguez ML (2018): Monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) as a promising therapeutic target. Biochemical pharmacology. 157:18–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Clapper JR, Henry CL, Niphakis MJ, Knize AM, Coppola AR, Simon GM, et al. (2018): Monoacylglycerol Lipase Inhibition in Human and Rodent Systems Supports Clinical Evaluation of Endocannabinoid Modulators. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 367:494–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pilon P (2017): Abide Therapeutics Reports Positive Topline Data from Phase 1b Study of ABX-1431 in Tourette Syndrome. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Aida J, Fushimi M, Kusumoto T, Sugiyama H, Arimura N, Ikeda S, et al. (2018): Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of Piperazinyl Pyrrolidin-2-ones as a Novel Series of Reversible Monoacylglycerol Lipase Inhibitors. J Med Chem. 61:9205–9217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pava MJ, Makriyannis A, Lovinger DM (2016): Endocannabinoid Signaling Regulates Sleep Stability. PloS one. 11:e0152473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hruba L, Seillier A, Zaki A, Cravatt BF, Lichtman AH, Giuffrida A, et al. (2015): Simultaneous inhibition of fatty acid amide hydrolase and monoacylglycerol lipase shares discriminative stimulus effects with Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol in mice. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 353:261–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Long JZ, Nomura DK, Vann RE, Walentiny DM, Booker L, Jin X, et al. (2009): Dual blockade of FAAH and MAGL identifies behavioral processes regulated by endocannabinoid crosstalk in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106:20270–20275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hartley ND, Gunduz-Cinar O, Halladay L, Bukalo O, Holmes A, Patel S (2016): 2-arachidonoylglycerol signaling impairs short-term fear extinction. Translational psychiatry. 6:e749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Llorente-Berzal A, Terzian AL, di Marzo V, Micale V, Viveros MP, Wotjak CT (2015): 2-AG promotes the expression of conditioned fear via cannabinoid receptor type 1 on GABAergic neurons. Psychopharmacology. 232:2811–2825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Rey AA, Purrio M, Viveros MP, Lutz B (2012): Biphasic effects of cannabinoids in anxiety responses: CB1 and GABA(B) receptors in the balance of GABAergic and glutamatergic neurotransmission. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 37:2624–2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wenzel JM, Cheer JF (2014): Endocannabinoid-dependent modulation of phasic dopamine signaling encodes external and internal reward-predictive cues. Front Psychiatry. 5:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Owens RA, Mustafa MA, Ignatowska-Jankowska BM, Damaj MI, Beardsley PM, Wiley JL, et al. (2017): Inhibition of the endocannabinoid-regulating enzyme monoacylglycerol lipase elicits a CB1 receptor-mediated discriminative stimulus in mice. Neuropharmacology. 125:80–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Goetghebeur PJ, Swartz JE (2016): True alignment of preclinical and clinical research to enhance success in CNS drug development: a review of the current evidence. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England). 30:586–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Gunn RN, Rabiner EA (2017): Imaging in Central Nervous System Drug Discovery. Semin NuclMed. 47:89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hattori Y, Aoyama K, Maeda J, Arimura N, Takahashi Y, Sasaki M, et al. (2019): Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of (4 R)-1-{3-[2-((18)F)Fluoro-4-methylpyridin-3-yl]phenyl}-4-[4-(1,3-thiazol-2-ylcarbo nyl)piperazin-1-yl]pyrrolidin-2-one ([(18)F]T-401) as a Novel Positron-Emission Tomography Imaging Agent for Monoacylglycerol Lipase. J Med Chem. 62:2362–2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Chen Z, Mori W, Deng X, Cheng R, Ogasawara D, Zhang G, et al. (2019): Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of Reversible and Irreversible Monoacylglycerol Lipase Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Tracers Using a “Tail Switching” Strategy on a Piperazinyl Azetidine Skeleton. J Med Chem. 62:3336–3353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Cheng R, Mori W, Ma L, Alhouayek M, Hatori A, Zhang Y, et al. (2018): In Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation of (11)C-Labeled Azetidinecarboxylates for Imaging Monoacylglycerol Lipase by PET Imaging Studies. J Med Chem. 61:2278–2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ahamed M, Attili B, van Veghel D, Ooms M, Berben P, Celen S, et al. (2017): Synthesis and preclinical evaluation of [(11)C]MA-PB-1 for in vivo imaging of brain monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL). European journal of medicinal chemistry. 136:104–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wang L, Mori W, Cheng R, Yui J, Hatori A, Ma L, et al. (2016): Synthesis and Preclinical Evaluation of Sulfonamido-based [(11)C-Carbonyl]-Carbamates and Ureas for Imaging Monoacylglycerol Lipase. Theranostics. 6:1145–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Hariri AR, Gorka A, Hyde LW, Kimak M, Halder I, Ducci F, et al. (2009): Divergent effects of genetic variation in endocannabinoid signaling on human threat-and reward-related brain function. Biological psychiatry. 66:9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hammoud MZ, Peters C, Hatfield JRB, Gorka SM, Phan KL, Milad MR, et al. (2019): Influence of Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol on long-term neural correlates of threat extinction memory retention in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 44:1769–1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Gunduz-Cinar O, MacPherson KP, Cinar R, Gamble-George J, Sugden K, Williams B, et al. (2013): Convergent translational evidence of a role for anandamide in amygdala-mediated fear extinction, threat processing and stress-reactivity. Molecular psychiatry. 18:813–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Gomes-de-Souza L, Oliveira LA, Benini R, Rodella P, Costa-Ferreira W, Crestani CC (2016): Involvement of endocannabinoid neurotransmission in the bed nucleus of stria terminalis in cardiovascular responses to acute restraint stress in rats. British journal of pharmacology. 173:2833–2844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Morena M, Berardi A, Colucci P, Palmery M, Trezza V, Hill MN, et al. (2018): Enhancing Endocannabinoid Neurotransmission Augments The Efficacy of Extinction Training and Ameliorates Traumatic Stress-Induced Behavioral Alterations in Rats. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 43:1284–1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Balogh Z, Szente L, Biro L, Varga ZK, Haller J, Aliczki M (2019): Endocannabinoid interactions in the regulation of acquisition of contextual conditioned fear. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry. 90:84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Fontenot J, Loetz EC, Ishiki M, Bland ST (2018): Monoacylglycerol lipase inhibition alters social behavior in male and female rats after post-weaning social isolation. Behav Brain Res. 341:146–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Aliczki M, Varga ZK, Balogh Z, Haller J (2015): Involvement of 2-arachidonoylglycerol signaling in social challenge responding of male CD1 mice. Psychopharmacology. 232:2157–2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.