Abstract

Summary

We report the case of a 76-year-old male with a remote history of papillary thyroid cancer who developed severe paroxysmal headaches in the setting of episodic hypertension. Brain imaging revealed multiple lesions, initially of inconclusive etiology, but suspicious for metastatic foci. A search for the primary malignancy revealed an adrenal tumor, and biochemical testing confirmed the diagnosis of a norepinephrine-secreting pheochromocytoma. Serial imaging demonstrated multiple cerebral infarctions of varying ages, evidence of vessel narrowing and irregularities in the anterior and posterior circulations, and hypoperfusion in watershed areas. An exhaustive work-up for other etiologies of stroke including thromboembolic causes or vasculitis was unremarkable. There was resolution of symptoms, absence of new infarctions, and improvement in vessel caliber after adequate alpha-adrenergic receptor blockade for the management of pheochromocytoma. This clinicoradiologic constellation of findings suggested that the etiology of the multiple infarctions was reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS). Pheochromocytoma remains a poorly recognized cause of RCVS. Unexplained multifocal cerebral infarctions in the setting of severe hypertension should prompt the consideration of a vasoactive tumor as the driver of cerebrovascular dysfunction. A missed or delayed diagnosis has the potential for serious neurologic morbidity for an otherwise treatable condition.

Learning points:

The constellation of multifocal watershed cerebral infarctions of uncertain etiology in a patient with malignant hypertension should trigger the consideration of undiagnosed catecholamine secreting tumors, such as pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas.

Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome is a serious but reversible cerebrovascular manifestation of pheochromocytomas that may lead to strokes (ischemic and hemorrhagic), seizures, and cerebral edema.

Alpha-adrenergic receptor blockade can reverse cerebral vasoconstriction and prevent further cerebral ischemia and infarctions.

Early diagnosis of catecholamine secreting tumors has the potential for reducing neurologic morbidity and mortality in patients presenting with cerebrovascular complications.

Patient Demographics: Adult, Male, White, United States

Clinical Overview: Adrenal, Adrenal, Noradrenaline, Normetanephrine, Phaeochromocytoma, Hypertension, Papillary thyroid cancer

Diagnosis and Treatment: Headache, Hypertension, Sleep hyperhidrosis, Nausea, Vomiting, Syncope, Blood pressure, MRI, CT scan, Normetanephrine, Norepinephrine, MIBG scan, Echocardiogram, Ultrasound scan, Angiography, Troponin, Haemoglobin A1c, Vanillylmandelic acid (24-hour urine), Chromogranin A, Androstenedione, Cortisol, ACTH, Lymph node dissection, Thyroidectomy, Radiotherapy, Resection of tumour, Alpha-blockers, Phenoxybenzamine, Radioiodine, Diltiazem, Metoprolol, Beta-blockers, Triamterene, Hydrochlorothiazide, Epinephrine

Related Disciplines: Neurology

Publication Details: Unique/unexpected symptoms or presentations of a disease, August, 2020

Background

Pheochromocytomas are a rare neoplasm of the chromaffin cells with an incidence of 0.8–0.95 per 100 000-person years (1). Paroxysmal neurologic symptoms are common, presenting symptoms of patients with pheochromocytomas, occurring in up to 73% of patients (2). Headaches are the most common complaint, although severe neurological manifestations, including intracerebral hemorrhage, cerebral infarction, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES), and intracranial arterial dissection may occur (3, 4). A special consideration in patients with pheochromocytomas is reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS). Diagnostic criteria for RCVS includes the presence of a ‘thunderclap’ or severe recurrent headache, cerebral vasoconstriction on imaging in at least two different cerebral arteries and resolution of vasoconstriction by 3 months (5). Neurological sequelae, including strokes (ischemic and hemorrhagic), seizures, and cerebral edema, have been described as a result of RCVS (6).

Case presentation

We present the case of a 76-year-old male with a remote history of papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) who developed severe paroxysmal headaches, night sweats, nausea, and vomiting, along with elevated systolic blood pressures >200 mmHg during these events. The patient was diagnosed with metastatic PTC with cervical lymph node and intraglandular metastases at the age of 43. He was treated surgically with subtotal thyroidectomy and lymph node dissection followed by post-operative radioactive iodine ablation therapy (100 mCi of I-131). He did well until the age of 63, when he was found to have neck recurrence. A lymph node dissection (5/5 lymph nodes positive for PTC) was performed and once again he received post-operative radioactive iodine for anterior linear uptake in the neck. Subsequently, he had routine cancer surveillance and thyrogen whole body scans performed at the 5- and 10-year mark after his last surgery showed no evidence of disease recurrence.

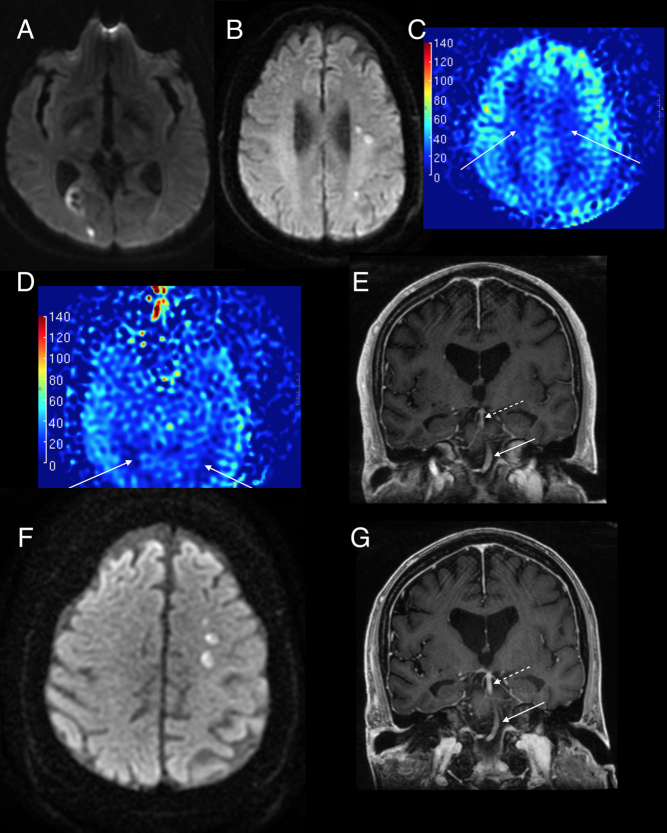

In order to evaluate his severe headaches, he underwent a non-contrast MRI of his brain which revealed multiple foci of increased diffusion and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) signal within the supratentorial brain involving both hemispheres and the anterior and posterior circulations, the largest of which was in the right parieto-occipital region with intrinsic hemorrhage and mild hyperperfusion (Fig. 1A). In addition, cortical-based FLAIR lesions were seen in the border zone between the MCA/PCA territory on the left (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Brain MRI. Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) showing (A) right parieto-occipital lesion (with intrinsic hemorrhage) without restriction on ADC along with contrast enhancement (not shown) indicating they are subacute infarcts and (B) left MCA watershed infarcts in the centrum semiovale. (C) Arterial spin labeling (ASL) perfusion showing hypoperfusion (darker blue) in the bilateral MCA, and bilateral MCA-PCA watershed areas. (D) Corresponding ASL perfusion shows hypoperfusion in the PCA territories (white arrows). (E) The caliber of the distal basilar artery (dotted arrow) is narrower compared to the proximal basilar artery (solid white arrow). (F) New left MCA watershed infarcts in the centrum semiovale while α-blocker (phenoxybenzamine) titration still ongoing. (G) Improvement in the caliber and flow in the terminal basilar artery on serial imaging (12 weeks) after the image (D) as patient’s blood pressures were adequately controlled with phenoxybenzamine.

Investigation

Given the history of metastatic malignancy, this was concerning for intraparenchymal and leptomeningeal metastatic disease prompting consideration of stereotactic brain biopsy with referral to a neurooncological surgeon. Cross-sectional imaging of the neck was unremarkable but CT of the abdomen and pelvis in search of metastatic disease revealed a hypervascular, heterogenous right adrenal mass measuring 6.3 × 5.2 cm. Laboratory work-up (Table 1) was significant for elevated serum normetanephrine of 12 nmol/L (normal <0.9), urine norepinephrine of 522 µg/24 h (normal <80) and urine normetanephrine 2692 µg/24 h (normal <900). A confirmatory metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scan revealed the I-123 MIBG-avid lesion consistent with pheochromocytoma.

Table 1.

Results of biochemical work-up undertaken given the history of papillary thyroid cancer and new adrenal mass discovered during evaluation of cerebral lesions.

| Laboratory values | Reference range | Patient |

|---|---|---|

| Thyroid function | ||

| TSH, µIU/mL | 0.27–4.20 | 1.21 |

| Free thyroxine, ng/dL | 0.93–1.70 | 1.58 |

| Thyroglobulin Antibody, IU/mL | <4.0 | <1.0 |

| Thyroglobulin, ng/mL | <50.0 | <0.5 |

| Neuroendocrine | ||

| Chromogranin A, ng/mL | <93 | 403 |

| Adrenal hormones | ||

| Androstenedione, ng/dL | ||

| Males >18 years | 40–190 | 19 |

| DHEA, µg/dL | ||

| Males >60 years | 30–150 | 31.0 |

| ACTH, pg/mL | 7.2–63.3 | 3.6* |

| Cortisol, µg/dL | ≥2.0 | 1.3* |

| Free Normetanephrines, nmol/L | <0.90 | 12 |

| Free Metanephrines, nmol/L | <0.50 | 0.39 |

| 24-h urine studies | ||

| Norepinephrine, µg/24 h | 15–80 | 522 |

| Normetanephrine, µg/24 h | 2692 | |

| Normotensive | 148–560 | |

| Hypertensive | <900 | |

| Epinephrine, µg/24 h | <21 | 14 |

| Metanephrine, µg/24 h | 244 | |

| Normotensive | 44–261 | |

| Hypertensive | <400 | |

| Dopamine, µg/24 h | 65–400 | 101 |

| VMA, mg/24 h | <8 | 18.9 |

| Renal hormones | ||

| Plasma renin activity, ng/mL/h | ||

| Na-replete, upright | <0.6–3 | 2.6 |

| Aldosterone, ng/dL | <21 | <4 |

| Cardiovascular | ||

| Troponin I (peak), ng/mL | <0.055 | 0.231 |

| Creatine kinase, U/L | 39–308 | 83 |

| HbA1c, % | <5.7 | 6.9 |

*These values were measured 2 days after the patient was initiated on oral dexamethasone therapy for newly discovered cerebral lesions on MRI of the brain.

Abnormal values are presented in bold.

ACTH, adrenocorticotrophic hormone; DHEA, DHEA sulfate; HbA1C, glycosylated hemoglobin; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; VMA, vanillylmandelic acid.

Alpha-adrenergic receptor blockade via phenoxybenzamine was prescribed, leading to resolution of initial neurologic symptoms of headaches and presyncope. After 6 weeks of phenoxybenzamine therapy, with incomplete blood pressure control at the time, repeat MRI was performed demonstrating the evolving prior lesions and five additional new small lesions in the left middle cerebral artery watershed areas. As before, some of these areas were enhancing with contrast but did not have restricted diffusion, suggesting subacute infarcts (Fig. 1F). In addition, the arterial spin labeling (ASL) perfusion showed hypoperfusion in the anterior and posterior watershed border zones (Fig. 1C and D). Although a dedicated MR angiogram was not performed, BRAVO sequences showed thready basilar artery and left middle cerebral artery (Fig. 1E). Interval resolution of previously noted enhancement in the right parieto-occipital region and the posterior watershed FLAIR lesions was noted. The patient was seen by stroke neurology who favored subacute infarcts rather than intracranial metastases.

A comprehensive stroke work-up was pursued (Table 2) and the etiology of the strokes was thought to be either embolic or vasospasm from pheochromocytoma induced catecholamine surges. Serial MRIs over a span of 3 months during titration of alpha-blockade did not demonstrate new lesions or growth of prior lesions.

Table 2.

Summary of pertinent cardiovascular and neurovascular pre-operative testing.

| Pre-operative testing | |

|---|---|

| Transthoracic echocardiography | Normal left ventricular size with low normal systolic function (LVEF 50–55%) and moderate left ventricular hypertrophy with stage 1 diastolic dysfunction. Left atrial enlargement. Aortic valve sclerosis without stenosis and mild aortic regurgitation. Normal pulmonary artery pressure. No intracardiac thrombi seen. |

| Cardiac rhythm monitoring | No complex arrhythmia, occasional supraventricular ectopic beats (2.1% burden) |

| Myocardial perfusion scan | No evidence of significant jeopardized viable myocardium or prior myocardial infarction. Mild global hypokinesis. LVEF 43%. |

| Carotid duplex ultrasonography | Mild stable plaque of bilateral carotid arteries with no significant right internal carotid artery stenosis (<50%) |

Treatment

The patient ultimately required 140 mg/day of phenoxybenzamine in addition to diltiazem 120 mg twice daily, metoprolol 25 mg twice daily and triamterene-hydrochlorothiazide 37.5/25 mg daily before blood pressures were at goal. Given adequate control of symptoms and stability of neuroimaging, his adrenal tumor was resected 3 months after diagnosis. Despite excellent pre-operative alpha-blockade, the patient’s blood pressure was very labile during tumor manipulation with systemic systolic blood pressure >200 mmHg. As embolic stroke was on the differential for patient’s initial neurologic findings, an intra-operative transesophageal echocardiogram was performed showing no evidence of left atrial appendage thrombus, valvular vegetation, or intra-atrial shunt.

Outcome and follow-up

Patient was extubated uneventfully but required vasopressin and epinephrine infusions for post-resection shock. By post-operative day 1, he was off vasoactive support. CT angiography on post-operative day 4 demonstrated no flow-limiting stenosis, occlusion, or aneurysm in the intracranial and extracranial circulations. However, this did show a few areas of residual small vessel irregularities in the distal branches of the left middle cerebral artery and posterior cerebral arteries. An insertable cardiac monitoring system was placed, which after 6 months showed no evidence of atrial fibrillation. MRI performed 3 months after tumor resection showed no abnormal enhancement, intracranial infarcts, or hemorrhage. There was an improvement in caliber and flow in the terminal basilar artery on imaging 12 weeks after resection (Fig. 1G).

Discussion

Pheochromocytoma is often described as the great mimic and while paroxysmal neurological symptoms like headaches are common, cerebral infarctions remain a rare manifestation. Cerebrovascular manifestations in pheochromocytoma can be broken down into two categories; one where blood pressure surges test the boundaries of cerebral autoregulation leading to hyperperfusion induced endothelial injury, vasogenic edema and hemorrhage, and the other where catecholamine excess leads to cerebral vasoconstriction resulting in hypoperfusion, ischemia, and vasogenic edema. Elevated circulating catecholamines also enhance platelet aggregation increasing the risk of thrombosis and ischemic stroke. A survey of the cerebrovascular pathology seen in pheochromocytomas is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Review of cerebrovascular disease in pheochromocytoma.

| Case | Age, years | Sex | Cerebrovascular findings | Suspected/theorized pathology | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 31 | F | Multiple foci of intracranial vascular narrowing improved after tumor resection | RCVS | English et al. (7) |

| 2 | 13 | F | Hyperintense signals on bilateral caudate, lentiform, dentate nuclei and periventricular and deep white matter + subacute and chronic in globus pallidus and external capsule respectively | PRES | Serter et al. (16) |

| 3 | 40 | M | Segmental constriction of multiple secondary and tertiary cerebral vessels | Cerebral vasoconstriction | Armstrong et al. (11) |

| 4 | 44 | F | Multiple cerebral infarctions in bilateral frontal-parietal lobes and left occipital lobe. Arteriography with vessel wall irregularity and stenosis. Occlusion of left ICA at its origin | Cerebral vasospasm | Ueda et al. (4) |

| 5 | 45 | F | Multifocal narrowing in the branches of pericallosal, anterior + posterior cerebral arteries | Cerebral vasoconstriction | Anderson et al. (2) |

| 6 | 32 | F | T2 hyperintensities with restricted diffusion in bilateral occipital and left parietal lobe. Reduction in right MCA caliber. Subarachnoid hemorrhage. | RCVS with cerebral infarction | Anderson et al. (2) |

| 7 | 15 | F | Left parieto-occipital hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage. T2 hyperintensity in white matter of bilateral cerebral hemispheres | PRES | Anderson et al. (2) |

| 8 | 34 | F | Multifocal bilateral narrowing in the anterior and posterior circulation | RCVS (pseudovasculitis) | Razavi et al. (12) |

| 9 | 54 | F | Thrombotic occlusions of right middle cerebral and bilateral intracranial carotid arteries, multiple hemorrhages and infarctions in cerebrum, cerebellum, and brainstem | DIC, cerebral vasospasm | Hill et al. (8) |

| 10 | 43 | F | Multifocal diffuse narrowing of right middle cerebral artery and narrowing of distal basilar artery, bilateral occipital hyperintensities on T2-weighted FLAIR | PRES + RCVS with cerebral infarction | Majic et al. (3) |

| 11 | 14 | F | Severe stenosis of left internal carotid artery, occlusion of anterior cerebral artery and occlusion of descending branch of middle cerebral artery | RCVS | Inatomi et al. (9) |

| 12 | 47 | F | Multifocal infarcts in multiple vascular territories, multiple segments of stenosis of intracranial arteries, multifocal parenchymal hemorrhages with areas of hypodensity suggestive of ischemia | RCVS | Rupala et al. (10) |

DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy; PRES, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome; RCVS, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome.

Our patient sought care for severe paroxysmal headaches and brain imaging revealed multiple lesions of unclear etiology. Due to a remote history of malignancy, these were initially thought to be metastatic foci. Evaluation for extracerebral metastatic disease revealed an adrenal mass. Once the diagnosis of pheochromocytoma was made, alpha-blockade was initiated and repeat imaging several weeks into therapy showed the evolution of lesions, now favored to be infarcts of varying ages. The puzzling MRI findings especially watershed distribution raised the suspicion for cerebral vasospasm as opposed to embolic etiologies of stroke including artery to artery embolism, atrial fibrillation, valvular vegetation, severe cardiomyopathy with intracardiac thrombus, and intra-atrial shunt. No new lesions were found after appropriate alpha-blockade, and there was no recurrence of neurological symptoms or new cerebral infarcts after tumor resection.

Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction has been attributed as the cause of multifocal infarctions in pheochromocytoma (2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 9, 10). Diagnosis of RCVS requires the presence of thunderclap headaches or recurrent severe headaches along with angiographic evidence of segmental vessel constriction in at least 2 arteries that is reversible within 3 months in the absence of cerebral vasculitis and aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (5). Non-traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage has been seen in RCVS as focal lesions in high convexity sulci.

The first case of cerebral vasoconstriction in pheochromocytoma was described by Armstrong and Hayes in 1961 (11) and while the patient did not consent to angiography after tumor resection, 2-year follow-up revealed no further neurologic symptoms suggestive that the pathophysiology was reversible with the resolution of catecholamine excess. Further, it has been reported that alpha-1-receptor antagonism improves and halts the progression of cerebral vasculopathy seen in pheochromocytomas (9, 12). Interestingly, the angiographic pattern of diffuse cerebral vasoconstriction has been previously thought to be due to cerebral vasculitis (2, 3, 12) and treated with steroids, a therapy that has been linked to acute crises in pheochromocytoma (3, 13). This obviously creates a circumstance where the incorrect diagnosis and treatment may exacerbate the real pathology. Further, glucocorticoid therapy has independently been associated with clinicoradiologic worsening of RCVS and poor outcomes (14).

In a case series of 93 pheochromocytoma patients, cerebral angiography was performed in two patients showing multifocal cerebral vasoconstriction, which in one of those patients was initially attributed to vasculitis (2). The series reported another case of a postpartum patient with seizures and progressive coma who was found to have a narrowed MCA and large infarct with ‘wild swings’ in blood pressure who unfortunately passed away before treatment for pheochromocytoma. The series proposes that most strokes in patients with pheochromocytoma may be due to RCVS (2).

While our patient did not have dedicated vessel imaging pre-operatively, the post-contrast BRAVO sequences showed thready vessels in the anterior and posterior circulations, multiple cerebral infarctions of varying ages with a watershed zone predominance, hypoperfusion in the anterior and posterior watershed areas, absence of new lesions after adequate alpha-blockade, and absence of any other obvious stroke etiology after exhaustive work-up. This is strongly suggestive of cerebral vasoconstriction related cerebral ischemia. Interestingly, the largest lesion on initial MRI was in the right parieto-occipital region with signs of mild hyperperfusion along with cortical posterior watershed FLAIR lesions suggestive of PRES, a condition that has significant overlap with RCVS. Our patient’s calculated RCVS2 score, an approach developed by Rocha et al. (15) to distinguish RCVS from other intracranial arteriopathies, is 9 points (5 for recurrent severe headache, 3 for the presence of vasoconstrictive trigger, and 1 for subarachnoid hemorrhage). A score of 5 or higher was shown to have a positive predictive value of 98% for RCVS (sensitivity 94%, specificity 86%).

Although there are multiple reports of cerebrovascular disease in patients with pheochromocytoma, RCVS with cerebral infarctions remains a rare manifestation of a rare disease. The clinical constellation of severe hypertension and unexplained cerebrovascular events (especially multifocal infarctions) should raise the index of suspicion for a pheochromocytoma. Timely diagnosis and treatment can significantly impact neurologic morbidity and improve outcomes.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector

Patient consent

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient for publication of this article and accompanying images.

Author contribution statement

J M, A K, and F G M were involved in the perioperative management of the patient including pre-operative titration of alpha-blockade, work-up of cerebral lesions, intra-operative management, and the writing and editing of the manuscript. C V was involved in the writing of the manuscript, review of neurological imaging, and creation of the figure.

References

- 1.Beard CM, Sheps SG, Kurland LT, Carney JA, Lie JT. Occurrence of pheochromocytoma in Rochester, Minnesota, 1950 through 1979. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 1983. 58 802–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson NE, Chung K, Willoughby E, Croxson MS. Neurological manifestations of phaeochromocytomas and secretory paragangliomas: a reappraisal. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 2013. 84 452–457. ( 10.1136/jnnp-2012-303028) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Majic T, Aiyagari V. Cerebrovascular manifestations of pheochromocytoma and the implications of a missed diagnosis. Neurocritical Care 2008. 9 378–381. ( 10.1007/s12028-008-9105-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ueda N, Satoh S, Kuroiwa Y. Multiple cerebral infarction and cardiomyopathy with pheochromocytoma. Neurologist 2011. 17 34–37. ( 10.1097/NRL.0b013e3181d35c76) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burton TM, Bushnell CD. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. Stroke 2019. 50 2253–2258. ( 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.024416) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calabrese LH, Dodick DW, Schwedt TJ, Singhal AB. Narrative review: reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes. Annals of Internal Medicine 2007. 146 34–44. ( 10.7326/0003-4819-146-1-200701020-00007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.English SW, Nasr DM. Thunderclap headache and cerebral vasoconstriction secondary to pheochromocytoma. JAMA Neurology 2019. 76 502–503. ( 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.0001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill JB, Schwartzman RJ. Cerebral infarction and disseminated intravascular coagulation with pheochromocytoma. Archives of Neurology 1981. 38 395 ( 10.1001/archneur.1981.00510060097025) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inatomi Y, Yonehara T, Fujioka S, Uchino M. alpha-Blocker is effective in the improvement of cerebral angiopathy in a patient with pheochromocytoma. Cerebrovascular Diseases 2002. 13 76–77. ( 10.1159/000047753) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rupala K, Mittal V, Gupta R, Yadav R. Atypical presentation of pheochromocytoma: central nervous system pseudovasculitis. Indian Journal of Urology 2017. 33 82–84. ( 10.4103/0970-1591.195760) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armstrong FS, Hayes GJ. Segmental cerebral arterial constriction associated with pheochromocytoma: report of a case with arteriograms. Journal of Neurosurgery 1961. 18 843–846. ( 10.3171/jns.1961.18.6.0843) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Razavi M, Bendixen B, Maley JE, Shoaib M, Zargarian M, Razavi B, Adams HP. CNS pseudovasculitis in a patient with pheochromocytoma. Neurology 1999. 52 1088–1090. ( 10.1212/wnl.52.5.1088) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosas AL, Kasperlik-Zaluska AA, Papierska L, Bass BL, Pacak K, Eisenhofer G. Pheochromocytoma crisis induced by glucocorticoids: a report of four cases and review of the literature. European Journal of Endocrinology 2008. 158 423–429. ( 10.1530/EJE-07-0778) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singhal AB, Topcuoglu MA. Glucocorticoid-associated worsening in reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. Neurology 2017. 88 228–236. ( 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003510) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rocha EA, Topcuoglu MA, Silva GS, Singhal AB. RCVS2 score and diagnostic approach for reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. Neurology 2019. 92 e639–e647. ( 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006917) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serter A, Alkan A, Aralasmak A, Kocakoc E. Severe posterior reversible encephalopathy in pheochromocytoma: importance of susceptibility-weighted MRI. Korean Journal of Radiology 2013. 14 849–853. ( 10.3348/kjr.2013.14.5.849) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a