Abstract

Background

During adolescence, childhood and adult forms of tuberculosis (TB) overlap, resulting in diverse disease manifestations. Knowing which patient characteristics are associated with which manifestations may facilitate diagnosis and enhance understanding of TB pathophysiology.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, we included 10–19-year-olds in Ukraine's national TB registry who started TB treatment between 2015 and 2018. Using multivariable regression, we estimated associations between patient characteristics and four presentations of TB: pleural, extrathoracic, cavitary and rifampicin-resistant (RR). We also described the epidemiology of adolescent TB in Ukraine.

Results

Among 2491 adolescent TB cases, 88.4% were microbiologically confirmed. RR-TB was confirmed in 16.9% of new and 29.7% of recurrent cases. Of 88 HIV-infected adolescents, 59.1% were not on antiretroviral therapy at TB diagnosis. Among 10–14-year-olds, boys had more pleural disease (adjusted OR (aOR) 2.12, 95% CI: 1.08–4.37). Extrathoracic TB was associated with age 15–19 years (aOR 0.26, 95% CI: 0.18–0.37) and HIV (aOR 3.25, 95% CI: 1.55–6.61 in 10–14-year-olds; aOR 8.18, 95% CI: 3.58–17.31 in 15–19-year-olds). Cavitary TB was more common in migrants (aOR 3.53, 95% CI: 1.66–7.61) and 15–19-year-olds (aOR 4.10, 95% CI: 3.00–5.73); among 15–19-year-olds, it was inversely associated with HIV (aOR 0.32, 95% CI: 0.13–0.70). RR-TB was associated with recurrent disease (aOR 1.87, 95% CI: 1.08–3.13), urban residence (aOR 1.27, 95% CI: 1.01–1.62) and cavitation (aOR 2.98, 95% CI: 2.35–3.78).

Conclusions

Age, sex, HIV and social factors impact the presentation of adolescent TB. Preventive, diagnostic and treatment activities should take these factors into consideration.

Short abstract

Analysing 2491 cases of adolescent tuberculosis in Ukraine, associations were observed between four clinical presentations – cavitary, pleural, extrathoracic and rifampicin-resistant TB – and age, sex, HIV status, prior treatment and social factors. https://bit.ly/2XplZFt

Introduction

Adolescents—defined as people 10–19 years of age—account for an estimated 800 000 incident tuberculosis (TB) cases annually [1]. During adolescence, a transition from childhood forms of TB to adult-type TB occurs [2–7], resulting in diverse clinical presentations. Among adolescents with TB disease, 10–20% have pleural TB, 10–20% have extrathoracic TB, and approximately 25% have lung cavitation [6, 8–11]. The percentage of adolescents with rifampicin-resistant (RR) TB, which includes multidrug-resistant (MDR) TB (combined resistance to isoniazid and rifampicin), is largely unknown; however, data from several former Soviet countries have shown a higher RR-TB risk among adolescents and young adults than older age groups [12–14]. Pleural and extrathoracic TB are challenging to diagnose due to the difficulty of microbiological confirmation and nonspecific clinical presentations [15]. RR-TB is difficult to confirm in adolescents with culture-negative TB and in settings with limited drug susceptibility testing (DST). Both RR and cavitary TB require longer therapies and have worse outcomes. Knowing which patient characteristics are associated with pleural, extrathoracic and RR-TB may help clinicians make these challenging diagnoses. Identifying predictors of cavitary and RR-TB may help elucidate why some adolescents develop these severe disease forms, with the goal of identifying modifiable risk factors and therapeutic targets.

Our current understanding of adolescent TB comes primarily from observational studies conducted before the availability of anti-TB chemotherapy. These reports, along with a few recent publications, have described age- and sex-based patterns in clinical presentation, including more pleural TB in boys and a rise in lung cavitation in mid-adolescence [2–7]. Nonetheless, knowledge gaps remain. First, previous studies were descriptive and did not adjust for covariates. Second, since the pre-chemotherapy era, two major challenges to TB elimination have emerged: HIV and RR-TB [16]. We know little about how infection with HIV or RR Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) strains impacts adolescent TB presentation.

With its high incidence of RR-TB and TB/HIV coinfection, Ukraine is an ideal setting for evaluating the impact of these factors on adolescent TB. Analysing programmatic data from the Ukrainian National TB Program (NTP), we aimed to identify adolescent patient characteristics associated with pleural, extrathoracic, cavitary and RR-TB. As a secondary aim, we described the epidemiology of adolescent TB in Ukraine.

Methods

Setting

In 2018, Ukraine had an estimated TB incidence of 80 per 100 000 population; RR-TB prevalence was 29% among new and 46% among previously treated cases; and HIV-infected people accounted for 23% of all incident TB cases [16]. In a 2013–2014 national survey of anti-TB drug resistance, >40% of MDR-TB cases could be classified further as extensively drug-resistant (XDR) TB (additional resistance to a fluoroquinolone and a second-line injectable agent) or pre-XDR (additional resistance to a fluoroquinolone or a second-line injectable agent) [14].

According to Ukrainian NTP guidelines, evaluation for TB disease should include smear microscopy; mycobacterial culture; Xpert MTB/RIF (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA); DST to rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol, pyrazinamide and streptomycin for culture-positive isolates; HIV testing; and posterior–anterior and lateral chest radiographs (CXRs) [17, 18]. Computed tomography scans are obtained only when CXR results are equivocal. In the absence of microbiological confirmation, TB may be diagnosed based on symptoms, imaging findings and contact with a known TB case. The NTP has no specific guidelines for diagnosing extrapulmonary TB.

Data source

Since 2013, the NTP has required clinicians to enter standardised data for every TB patient into eTB Manager, which is an online case registry. NTP staff downloaded de-identified data from eTB Manager on November 9, 2018. We collected the following variables recorded at treatment initiation: age; sex; HIV status; antiretroviral therapy (ART) start date, if applicable; whether the TB episode is new or recurrent; urban versus rural residence; oblast (Ukrainian equivalent of a province) of residence; migration status; history of incarceration; excess alcohol use; anatomic site(s) of TB disease; and results of imaging, smear microscopy, culture, Xpert and DST. HIV viral loads and CD4 counts are not recorded in eTB Manager and so were unavailable.

Definitions

Consistently with previous studies, we referred to adolescents as “younger” (10–14 years old) and “older” (15–19 years old) [1, 19, 20]. Participants were classified as living in “urban” (cities) or “rural” (suburbs, towns, villages, farms) areas. We grouped internally displaced persons, immigrants and refugees together as “migrants”. “Excess alcohol use” was not defined by any standard criteria and was self-reported. Moreover, data fields pertaining to migration and alcohol were completed only when positive; we assigned negative responses to empty fields. We classified oblasts into “conflict-affected” (Donetsk and Luhansk, sites of armed conflict with Russia since 2015) and “nonconflict-affected” (the rest of Ukraine) [21]. eTB Manager data for conflict-affected oblasts were available from the areas under Ukrainian control only.

We defined “recurrent TB” as disease in a participant who was previously treated for TB, whose most recent anti-TB regimen ended ≥6 months ago, and who was cured or completed treatment at the end of that regimen [22]. We used “intrathoracic” to refer to the lung parenchyma, intrathoracic lymph nodes, pleura and/or pericardium, and “extrathoracic” to refer to any other site [23]. “Cavitary TB” and “pleural TB” were diagnosed by imaging.

“Microbiologic confirmation” was characterised by documentation of positive smear, positive culture, positive Xpert and/or a DST result. We defined “baseline DST” as a DST performed on a sample obtained prior to or ≤30 days after treatment initiation.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included people registered in eTB Manager who started a TB regimen between January 1, 2015 and November 9, 2018, and were 10–19 years old at treatment initiation. We excluded adolescents who began treatment before 2015 due to concerns about data quality during the first 2 years of eTB Manager's implementation. A participant could contribute >1 incident TB case if ≥6 months passed between the cure or treatment completion of one regimen and the initiation of a subsequent regimen.

Analysis

Using World Bank population estimates [24], we calculated the average annual age- and sex-specific reported TB incidence.

Using logistic regression, we estimated associations between patient characteristics at diagnosis and these clinical presentations: 1) TB with pleural involvement, compared to TB without pleural involvement; 2) TB with extrathoracic involvement, compared to exclusively intrathoracic TB; 3) cavitary pulmonary TB, compared to all other forms of TB; and 4) baseline RR-TB, compared to baseline rifampicin-susceptible (including isoniazid-monoresistant) TB. For the fourth outcome, we excluded subjects with no baseline DST result. We assessed the following predictors for all outcomes: age group, sex, HIV status, new versus recurrent TB, conflict-affected versus nonconflict-affected oblast, urban versus rural residence, migration status, history of incarceration and excess alcohol use. For the first three outcomes, we also included baseline rifampicin susceptibility. For the fourth outcome only, we added lung cavitation, which was associated with RR-TB in other former Soviet republics [25, 26].

Because age may modify the effect of sex and HIV infection on immune response to Mtb, we assessed interactions between age group and sex and HIV for all outcomes [27]. As different risk factors have been reported for transmitted versus acquired RR-TB [26, 28], we assessed interactions between DST result and new versus recurrent TB for the first three outcomes and between new versus recurrent TB and all other covariates for the fourth outcome. We built multivariable models by including all covariates and interaction terms with p<0.2 from univariable analysis.

HIV status and urban versus rural residence had small amounts of missing data, and half of the cases with missing HIV status had a documented HIV test date. Therefore, we assumed the lack of these variables was due to clerical errors and conducted complete-case analysis. For missing DST results, we used the missing indicator method to maximise the sample size in multivariable analysis for the first three outcomes. However, we did not report estimates for cases without a DST result because lack of data was mostly an artefact of the outcomes of interest (i.e. the four clinical presentations). Specifically, 289 of 328 (88.1%) cases without baseline DST result lacked documentation of smear or culture positivity; in these cases, we assumed DST could not be performed due to paucibacillary TB – which excludes cavitary disease – or inability to sample extrapulmonary sites. No other variables had missing values.

All analyses were conducted using R version 3.5.1.

Ethics

This study used nonidentifiable data collected during routine clinical care and, therefore, was deemed exempt from institutional review board (IRB) approval by Bogomolets National Medical University (Kyiv, Ukraine), Center for Public Health (Kyiv, Ukraine) and Boston University (Boston, MA, USA). The IRB of The Miriam Hospital (Providence, RI, USA) also approved this study and waived informed consent.

Results

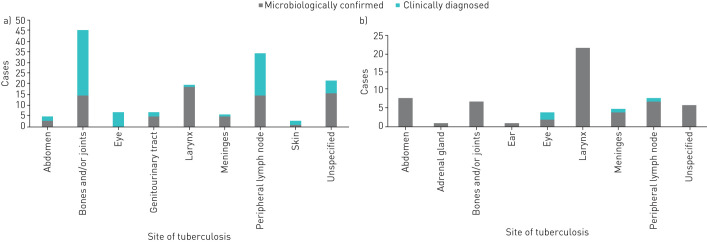

During the study period, the average annual reported adolescent TB incidence was 7.4 per 100 000 for younger adolescents, 27.8 per 100 000 for older adolescents, and 17.7 per 100 000 for all adolescents. TB notification rate increased throughout adolescence for both sexes (figure 1). Notification rates were comparable for girls and boys between ages 10–13 years, higher in girls between ages 14–15 years and higher in boys thereafter.

FIGURE 1.

Average annual tuberculosis notification rates in adolescents, stratified by age and sex, Ukraine, 2015–2017. Confidence intervals are omitted from this figure as we are presenting the actual notification rate rather than drawing inferences. Data from 2018 were excluded from this figure because there may be a delay of up to 3 months for entering cases into eTB Manager. As a result, even though the data for this analysis were downloaded from eTB Manager in November 2018, the number of notified adolescent TB cases in 2018 cannot be estimated with confidence. Of note, due to the lack of age- and sex-specific data on adolescent HIV prevalence in Ukraine, we could not stratify this analysis by HIV status.

We included 2491 incident TB cases among 2472 adolescents, of whom 19 (0.8%) contributed two cases each and therefore were considered twice in the cohort. Median age at treatment initiation was 17 years (interquartile range: 15–18). Sixty-nine of 2491 (2.8%) cases occurred in participants who received previous treatment for TB disease before the study period and/or before age 10 years. Among the 2385 cases with known HIV status, 88 (3.7%) were HIV-infected, of whom 52 (59.1%) were not on ART at TB treatment initiation. Table 1 further describes the cohort.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and baseline clinical features of adolescent tuberculosis cases, Ukraine, 2015–2018 (n=2491)

| Ages 10–14 years | Ages 15–19 years | Ages 10–19 years | |

| Subjects n (row %) | 557 (22.4) | 1934 (77.6) | 2491 (100) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 280 (50.3) | 901 (46.6) | 1181 (47.4) |

| Male | 277 (49.7) | 1033 (53.4) | 1310 (52.6) |

| HIV status | |||

| Infected, no ART start date documented | 1 (0.2) | 9 (0.5) | 10 (0.4) |

| Infected, not on ART at start of TB treatment | 29 (5.2) | 23 (1.2) | 52 (2.1) |

| Infected, on ART at start of TB treatment | 13 (2.3) | 13 (0.7) | 26 (1.0) |

| Uninfected | 479 (86.0) | 1818 (94.0) | 2297 (92.2) |

| Unknown | 35 (6.3) | 71 (3.6) | 106 (4.3) |

| Urban or rural residence | |||

| Urban | 292 (52.4) | 1137 (58.8) | 1429 (57.4) |

| Rural | 262 (47.1) | 784 (40.5) | 1046 (42.0) |

| Unknown | 3 (0.5) | 13 (0.7) | 16 (0.6) |

| Migration status | |||

| Migrant | 6 (1.1) | 26 (1.3) | 32 (1.3) |

| Nonmigrant | 551 (98.9) | 1908 (98.7) | 2469 (98.7) |

| Oblast | |||

| Conflict-affected | 28 (5.0) | 99 (5.1) | 127 (5.1) |

| Not conflict-affected | 529 (95.0) | 1835 (94.9) | 2364 (94.9) |

| History of alcohol use | |||

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 17 (0.9) | 17 (0.7) |

| No | 557 (100.0) | 1917 (99.1) | 2474 (99.3) |

| History of incarceration | |||

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 24 (1.2) | 24 (1.0) |

| No | 557 (100.0) | 1910 (98.8) | 2467 (99.0) |

| Probable source case identified | |||

| Yes | 110 (19.7) | 214 (11.1) | 324 (13.0) |

| No | 447 (80.3) | 1720 (88.9) | 2167 (87.0) |

| Case classification | |||

| New | 537 (96.4) | 1863 (96.3) | 2400 (96.3) |

| Recurrent | 20 (3.6) | 71 (3.7) | 91 (3.7) |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Microbiological | 446 (80.1) | 1756 (90.8) | 2202 (88.4) |

| Clinical | 111 (19.9) | 178 (9.2) | 289 (11.6) |

| Site of disease | |||

| Exclusively intrathoracic | 455 (81.7) | 1824 (94.3) | 2279 (91.5) |

| Exclusively extrathoracic | 85 (15.3) | 66 (3.4) | 151 (6.1) |

| Intra- and extrathoracic | 17 (3.1) | 44 (2.3) | 61 (2.4) |

| Lung cavitation | |||

| Cavitary pulmonary TB | 56 (10.1) | 638 (33.0) | 694 (27.9) |

| Noncavitary pulmonary TB | 264 (47.4) | 1076 (55.6) | 1340 (53.8) |

| No pulmonary TB | 237 (42.5) | 220 (11.4) | 457 (18.3) |

| Pleural TB | |||

| Isolated pleural | 30 (5.4) | 131 (6.8) | 161 (6.5) |

| Pleural+pulmonary | 12 (2.2) | 45 (2.3) | 57 (2.3) |

| No pleural involvement | 515 (92.4) | 1758 (90.9) | 2273 (91.2) |

| Baseline drug resistance profile | |||

| INH- and RIF-susceptible | 379 (68.0) | 1289 (66.6) | 1668 (67.0) |

| INH-monoresistant | 11 (2.0) | 108 (5.6) | 119 (4.8) |

| RR but not pre-XDR | 20 (3.6) | 153 (0.8) | 173 (6.8) |

| RR, no SLD DST | 11 (2.0) | 63 (3.3) | 74 (3.0) |

| Pre-XDR but not XDR | 12 (2.1) | 73 (10.8) | 85 (3.4) |

| XDR | 6 (1.1) | 38 (2.0) | 44 (1.8) |

| No result# | 118 (21.2) | 210 (10.9) | 328 (13.2) |

Data are presented as n (column %), unless otherwise stated. ART: antiretroviral therapy; TB: tuberculosis; INH: isoniazid; RIF: rifampicin; RR: rifampicin-resistant; SLD: second-line drug; DST: drug susceptibility testing; XDR: extensively drug-resistant. #: DST result was not documented in 39 (1.8%) of 2202 microbiologically confirmed cases.

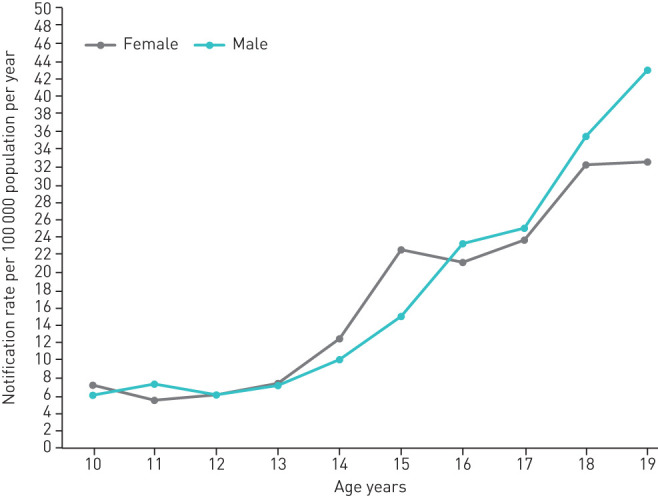

Of 2340 cases with intrathoracic involvement, 1900 (81.2%) involved lungs only; 160 (6.9%) involved pleura only; 145 (6.2%) involved intrathoracic lymph nodes only; 58 (2.5%) involved lungs and an extrathoracic site; 57 (2.4%) involved lungs and pleura; 17 (0.7%) involved lungs and intrathoracic lymph nodes; and three (0.1%) involved intrathoracic lymph nodes and an extrathoracic site. There were no cases of pericardial TB. Figure 2 shows the distribution of extrathoracic sites in the 212 cases with extrathoracic involvement.

FIGURE 2.

Frequency of extrathoracic sites involved in a) exclusively extrathoracic adolescent tuberculosis cases (n=151) and b) cases with both intra- and extrathoracic involvement (n=61), Ukraine, 2015–2018. There are no data on the site from which the specimen was obtained for microbiological confirmation (i.e. specimen could have been obtained from the respiratory tract or the extrathoracic site). Only one reported case involved >1 extrathoracic site, the abdomen and bones and/or joints.

Tables 2–4 show the patient characteristics associated with pleural, extrathoracic and cavitary TB. Among 10–14-year-olds, we observed more pleural disease in boys than girls (adjusted OR (aOR) 2.12, 95% CI: 1.08–4.37). Pleural TB was inversely associated with RR-TB (aOR 0.44, 95% CI: 0.25–0.74). Extrathoracic TB was less common among 15–19-year-olds (aOR 0.26, 95% CI: 0.18–0.37) and more common among HIV-infected participants (aOR 3.25, 95% CI: 1.55–6.61 in 10–14-year-olds; aOR 8.18, 95% CI: 3.58–17.31 in 15–19-year-olds). Cavitary TB was associated with age 15–19 years (aOR 4.10, 95% CI: 3.00–5.73) and, in 15–19-year-olds only, inversely associated with HIV (aOR 0.32, 95% CI 0.13–0.70). We also observed higher odds of cavitation in migrants (aOR 3.53, 95% CI: 1.66, 7.61) and participants who reported excess alcohol use (aOR 3.29, 95% CI: 1.20, 9.52).

TABLE 2.

Predictors of pleural disease among all tuberculosis cases (n=2491)

| n (% of subgroup) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age group | |||||

| 10–14 years | 42 (7.5) | Ref | |||

| 15–19 years | 176 (9.1) | 1.26 (0.89, 1.82) | 0.20 | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Female (10–14 years) | 14 (5.0) | Ref | |||

| Male (10–14 years) | 28 (10.1) | 2.14 (1.12, 4.27) | 0.025 | 2.12 (1.08, 4.37) | 0.034# |

| Female (15–19 years) | 72 (8.0) | Ref | |||

| Male (15–19 years) | 104 (10.1) | 1.29 (0.94, 1.77) | 0.14 | 1.29 (0.93, 1.80) | 0.13 |

| HIV status | |||||

| Uninfected | 206 (9.0) | Ref | |||

| Infected | 3 (3.4) | 0.36 (0.11, 1.14) | 0.083 | 0.41 (0.10, 1.13) | 0.14 |

| Case classification | |||||

| New | 214 (8.9) | Ref | |||

| Recurrent | 3 (3.3) | 0.35 (0.11, 1.11) | 0.074 | 0.38 (0.09, 1.03) | 0.10 |

| Oblast | |||||

| Not conflict-affected | 208 (8.8) | Ref | |||

| Conflict-affected | 9 (7.1) | 0.79 (0.37, 1.49) | 0.51 | ||

| Home setting | |||||

| Suburban/rural | 101 (9.0) | Ref | |||

| Urban | 115 (8.0) | 0.81 (0.61, 1.07) | 0.14 | 0.89 (0.67, 1.19) | 0.44 |

| Migration status | |||||

| Nonmigrant | 218 (8.9) | Ref | |||

| Migrant | 0 (0.0) | N/A | |||

| History of incarceration | |||||

| No | 217 (8.8) | Ref | |||

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | N/A | |||

| Excess alcohol use | |||||

| No | 216 (8.7) | Ref | |||

| Yes | 1 (5.9) | 0.65 (0.04, 3.22) | 0.68 | ||

| Baseline rifampicin susceptibility | |||||

| Susceptible | 153 (8.6) | Ref | |||

| Resistant | 15 (4.0) | 0.44 (0.25, 0.74) | 0.003 | 0.44 (0.25, 0.74) | 0.003# |

Only significant interactions are reported. N/A: not available. #: statistically significant using a cut-off of p<0.05.

TABLE 4.

Predictors of cavitary pulmonary tuberculosis among all tuberculosis cases (n=2491)

| n (% of subgroup) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age group | |||||

| 10–14 years | 56 (10.1) | Ref | |||

| 15–19 years | 638 (33.0) | 4.40 (3.32, 5.95) | <0.001 | 4.10 (3.00, 5.73) | <0.001# |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 313 (26.5) | Ref | |||

| Male | 381 (29.1) | 1.14 (0.95, 1.36) | 0.15 | 1.11 (0.91, 1.34) | 0.30 |

| HIV status | |||||

| Uninfected (10–14 years) | 47 (9.8) | Ref | |||

| Infected (10–14 years) | 7 (16.3) | 1.79 (0.70, 4.02) | 0.19 | 1.77 (0.67, 4.08) | 0.21 |

| Uninfected (15–19 years) | 605 (33.3) | Ref | |||

| Infected (15–19 years) | 8 (17.8) | 0.43 (0.19, 0.89) | 0.033 | 0.32 (0.13, 0.70) | 0.007# |

| Case classification | |||||

| New | 661 (27.5) | Ref | |||

| Recurrent | 33 (36.3) | 1.50 (0.96, 2.30) | 0.070 | 1.48 (0.91, 2.39) | 0.11 |

| Oblast | |||||

| Not conflict-affected | 655 (27.7) | Ref | |||

| Conflict-affected | 39 (30.7) | 1.16 (0.78, 1.69) | 0.46 | ||

| Home setting | |||||

| Suburban/rural | 288 (27.5) | Ref | |||

| Urban | 403 (28.2) | 1.03 (0.87, 1.24) | 0.71 | ||

| Migration status | |||||

| Nonmigrant | 677 (27.5) | Ref | |||

| Migrant | 17 (53.1) | 2.98 (1.48, 6.08) | 0.002 | 3.53 (1.66, 7.61) | 0.001# |

| History of incarceration | |||||

| No | 688 (27.9) | Ref | |||

| Yes | 6 (25.0) | 0.86 (0.31, 2.07) | 0.75 | ||

| Excess alcohol use | |||||

| No | 684 (27.6) | Ref | |||

| Yes | 10 (58.8) | 3.74 (1.43, 10.33) | 0.008 | 3.29 (1.20, 9.52) | 0.022# |

| Baseline rifampicin susceptibility | |||||

| Susceptible | 462 (25.9) | Ref | |||

| Resistant | 197 (52.4) | 3.16 (2.51, 3.97) | <0.001 | 2.98 (2.35, 3.78) | <0.001# |

Only significant interactions are reported. #: statistically significant using a cut-off of p<0.05.

TABLE 3.

Predictors of extrathoracic involvement among all tuberculosis cases (n=2491)

| n (% of subgroup) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age group | |||||

| 10–14 years | 99 (17.8) | Ref | |||

| 15–19 years | 91 (4.7) | 0.23 (0.17, 0.31) | <0.001 | 0.26 (0.18, 0.37) | <0.001# |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 84 (7.1) | Ref | |||

| Male | 106 (8.1) | 1.15 (0.85, 1.55) | 0.36 | ||

| HIV status | |||||

| Uninfected (10–14 years) | 79 (16.5) | Ref | |||

| Infected (10–14 years) | 15 (34.9) | 2.71 (1.36, 5.25) | 0.004 | 3.25 (1.55, 6.61) | <0.001# |

| Uninfected (15–19 years) | 76 (4.2) | Ref | |||

| Infected (15–19 years) | 10 (22.2) | 6.55 (2.98, 13.26) | <0.001 | 8.18 (3.58, 17.31) | <0.001# |

| Case classification | |||||

| New | 182 (7.6) | Ref | |||

| Recurrent | 8 (8.8) | 1.17 (0.52, 2.32) | 0.67 | ||

| Oblast | |||||

| Not conflict-affected | 186 (7.9) | Ref | |||

| Conflict-affected | 4 (3.1) | 0.38 (0.14, 1.04) | 0.060 | 0.36 (0.12, 1.09) | 0.070 |

| Home setting | |||||

| Suburban/rural | 87 (8.3) | Ref | |||

| Urban | 102 (7.1) | 0.85 (0.63, 1.14) | 0.28 | ||

| Migration status | |||||

| Nonmigrant | 190 (7.7) | Ref | |||

| Migrant | 0 (0.0) | NA | NA | ||

| History of incarceration | |||||

| No | 189 (7.7) | Ref | |||

| Yes | 1 (4.2) | 0.52 (0.03, 2.51) | 0.53 | ||

| Excess alcohol use | |||||

| No | 188 (7.6) | Ref | |||

| Yes | 2 (11.8) | 1.62 (0.25, 5.80) | 0.52 | ||

| Baseline rifampicin susceptibility | |||||

| Susceptible | 98 (5.5) | Ref | |||

| Resistant | 12 (3.2) | 0.57 (0.29, 1.00) | 0.069 | 0.64 (0.32, 1.14) | 0.16 |

Only significant interactions are reported. #: statistically significant using a cut-off of p<0.05.

Of 2163 cases with a baseline DST result, the isolate was isoniazid- and rifampicin-susceptible in 1668 (77.1%); isoniazid-resistant but rifampicin-susceptible in 119 (7.1%); and RR in 376 (17.4%). Of the 302 RR-TB cases with second-line drug resistance profiles, 129 (42.7%) could be further classified as pre-XDR or XDR. At baseline, 16.9% of new and 29.7% of recurrent TB cases had confirmed rifampicin resistance. Stratified by age group, the percentages of RR-TB among new and recurrent cases, respectively, were 10.6% and 28.6% in younger adolescents and 18.6% and 30.0% in older adolescents. Table 5 shows the patient characteristics associated with RR-TB: recurrent TB (aOR 1.87, 95% CI: 1.08–3.13), urban residence (aOR 1.27, 95% CI: 1.01–1.62) and cavitary TB (aOR 2.98, 95% CI: 2.35–3.78). There were no significant interactions between new versus recurrent TB and the other predictors.

TABLE 5.

Predictors of rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis among incident cases with baseline drug susceptibility test results (n=2163)

| n (% of subgroup) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age group | |||||

| 10–14 years | 49 (11.2) | Ref | |||

| 15–19 years | 327 (19.0) | 1.86 (1.36, 2.59) | <0.001 | 1.33 (0.96, 1.88) | 0.094 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 165 (15.9) | Ref | |||

| Male | 211 (18.7) | 1.22 (0.97, 1.52) | 0.09 | 1.19 (0.95, 1.50) | 0.14 |

| HIV status | |||||

| Uninfected | 360 (17.9) | Ref | |||

| Infected | 15 (20.0) | 1.15 (0.62, 1.99) | 0.64 | ||

| Case classification | |||||

| New | 354 (16.9) | Ref | |||

| Recurrent | 22 (29.7) | 2.07 (1.22, 3.41) | 0.005 | 1.87 (1.08, 3.13) | 0.021# |

| Oblast | |||||

| Not conflict-affected | 355 (17.3) | Ref | |||

| Conflict-affected | 21 (19.6) | 1.17 (0.70, 1.87) | 0.53 | ||

| Home setting | |||||

| Suburban/rural | 139 (15.4) | Ref | |||

| Urban | 234 (18.8) | 1.27 (1.01, 1.61) | 0.039 | 1.27 (1.01, 1.62) | 0.047# |

| Migration status | |||||

| Nonmigrant | 369 (17.3) | Ref | |||

| Migrant | 7 (25.9) | 1.68 (0.65, 3.82) | 0.24 | ||

| History of incarceration | |||||

| No | 370 (17.3) | Ref | |||

| Yes | 6 (26.1) | 1.69 (0.61, 4.09) | 0.27 | ||

| Excess alcohol use | |||||

| No | 371 (17.3) | Ref | |||

| Yes | 5 (35.7) | 2.66 (0.81, 7.75) | 0.08 | 2.07 (0.62, 6.26) | 0.21 |

| Cavitary tuberculosis | |||||

| No | 163 (12.5) | Ref | |||

| Yes | 197 (30.0) | 2.98 (2.36, 3.77) | <0.001 | 2.81 (2.21, 3.58) | <0.001# |

| Not applicable (no lung involvement) | 16 (7.9) | 0.60 (0.35, 1.03) | 0.063 | 0.64 (0.36, 1.07) | 0.11 |

Only significant interactions are reported. #: statistically significant using a cut-off of p<0.05.

Discussion

In this study, we have estimated independent associations between patient characteristics and clinical presentations of adolescent TB. We also have described the epidemiology of adolescent TB in Ukraine. Several of our results—such as the age- and sex-related patterns in lung cavitation and pleural TB—confirm previous descriptive reports, but our analysis adjusted for covariates [2–7]. In our cohort, the steepest rise in TB incidence in girls occurs right after the average age of menarche in Ukraine, which is 12.9 years [29]. These findings suggest interactions between pubertal hormones and host response to Mtb; other factors, including increased exposure to TB, may also contribute. Evidence for and against these and other explanations for age- and sex-related patterns in TB presentation have been extensively reviewed elsewhere [27].

To our knowledge, previous studies have not examined the impact of HIV coinfection, RR or social factors on adolescent TB presentation. In our cohort, two-thirds of HIV-infected participants with known ART start date had not received ART before TB diagnosis. This finding raises concern for gaps in adolescent HIV care, and means that HIV coinfection is a reasonable surrogate for immunosuppression in this group. The rise in cavitary TB incidence during adolescence is believed to be caused by the bolstering of host response to Mtb by pubertal hormones [27]. Our observation of an inverse association between HIV coinfection and lung cavitation in older adolescents—which mirrors findings from studies in adults—supports this hypothesis [30, 31]. The low number of 10–14-year-olds with cavitary TB may explain the lack of association between HIV and cavitation in the younger group. Unsurprisingly, in both age groups, HIV was associated with extrathoracic TB, which arises from progression or re-activation of distal sites of infection attributable to immunological failure to contain Mtb in the lungs.

We observed that compared to adolescents with rifampicin-susceptible TB, those with RR-TB had three-times the odds of lung cavitation at diagnosis. As resistance-conferring mutations in the Mtb genome occur at fixed frequencies, the higher bacillary load found in cavities predisposes to de novo resistance [32]. Another possible explanation for this observation is that Mtb genotype is a confounder associated with both cavitary disease and RR-TB. A study from Russia found an association between radiographically advanced disease, including widespread cavitation and Beijing-family strains—which are associated with RR-TB [33]. Studies from other locations did not find an association between Beijing-family strains and cavitation [34, 35]; however, Beijing subtypes in former Soviet republics may have a different predilection for causing cavities or another Mtb strain may be responsible. Because eTB Manager does not include data on genotype, we could not assess its relationship with clinical presentation. We also found that participants with baseline RR-TB had half the odds of pleural TB. The same hypotheses may explain this inverse association: because pleural TB is paucibacillary, de novo resistance may be less likely to emerge or Mtb genotype may be a confounder.

We observed associations between social factors and RR-TB and cavitary TB. Urban residents had higher odds of RR-TB compared to rural residents. Previous studies have reported this association among adults in Ukraine [36, 37]. Therefore, compared to adolescents living in rural areas, those in urban areas have a higher risk of exposure to RR-TB. In our cohort, migrants and excess alcohol users had increased odds of cavitary TB; however, these results should be interpreted with caution, given the limitations in how migration and excess alcohol use were reported. In Ukraine, both migrants and excess alcohol users face healthcare barriers [38–40]. Treatment delay, which has been associated with lung cavitation in adults with TB, may explain our finding [41, 42]. It is also possible that alcohol—or another factor associated with alcohol use, such as cigarette smoking—alters host response to Mtb in a way that predisposes to cavitation. Further investigation is needed to confirm and elucidate the relationships that we observed between social factors and severe forms of TB.

Only a few publications have reported the burden of RR-TB in adolescence [12, 43]. In our cohort, 17% of new adolescent TB cases had RR-TB, compared to 29% reported for all ages [16]. We are unsure of the reasons behind this difference in prevalence, particularly because the national drug resistance survey reported higher adjusted odds of RR-TB among 14–24-year-olds than in older age groups [14]. One potential explanation is that the finding in the national survey was driven by young adults 20–24 years of age. In Ukraine, the number of HIV infections is seven-times higher in 20–24-year-olds than in 10–19-year-olds, and HIV is an independent risk factor for RR-TB [14, 44, 45]. Another possibility is that compared to young adults, adolescents have less exposure to groups with more RR-TB—including not only HIV-infected people but also drug users and individuals with a history of incarceration. As a result, they are at lower risk for becoming infected with RR Mtb strains. These hypotheses warrant further investigation.

There was an even larger gap between the 30% of RR-TB among recurrent cases in our cohort and the 46% reported for all ages, but additional factors may have contributed to this difference [16]. First, the previously treated cases reported among all ages included patients who started a new regimen after the previous regimen ended in treatment failure or loss to follow-up. In contrast, our definition of recurrent TB did not include these patients, who are more likely to have RR-TB. Second, the drug resistance survey showed that, among previously treated patients, 35–54-year-olds had a higher risk of RR-TB than 15–24-year-olds [14]. Therefore, the higher prevalence of RR-TB in the general population likely is driven by older age groups.

This study has limitations. First, due to the lack of HIV viral load and CD4 count data, we could not further characterise the immunosuppression of HIV-infected participants and its relationship with clinical presentation. Second, excess alcohol use and migrant status were self-reported and data fields for these variables were completed only when positive. This limitation likely led to an underestimation of the prevalence of these factors. Third, as in any study that uses programmatic data, clerical errors may have occurred. We excluded TB cases reported before 2015 (during the eTB Manager roll-out period) to reduce this possibility. Fourth, the high proportion of microbiologically confirmed cases raises concern for the underdiagnosis of paucibacillary disease, including childhood-type pulmonary TB and extrathoracic TB. Last, the lack of NTP guidelines on extrapulmonary TB diagnosis and limited access to sampling procedures and advanced imaging may have contributed to misdiagnoses.

Despite these limitations, we have identified independent associations between patient characteristics and clinical manifestations of TB in a large adolescent cohort. These findings inform clinicians evaluating adolescents for TB, provide clues to TB pathophysiology and suggest targets for intervention to improve outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jeffrey Starke (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA), Joseph Hogan (Brown School of Public Health, Providence, RI, USA), Molly Franke (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA) and Elisabeth Lualdi (Brown University, Providence, RI, USA).

Footnotes

Author contributions: S.S. Chiang, M. Dolynska, N.R. Rybak, O. Aibana and H.E. Jenkins conceptualised the study. M. Dolynska, Y. Sheremeta, V. Petrenko, A. Mamotenko and I. Terleieva collected the data. S.S. Chiang and H.E. Jenkins conducted the analyses. S.S. Chiang, M. Dolynska, N.R. Rybak, A.T. Cruz, C.R. Horsburgh Jr and H.E. Jenkins interpreted the findings. S.S. Chiang drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed, revised and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of interest: S.S. Chiang reports grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study.

Conflict of interest: M. Dolynska has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: N.R. Rybak has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: A.T. Cruz has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: O. Aibana has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: Y. Sheremeta has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: V. Petrenko has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: A. Mamotenko has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: I. Terleeva has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: C.R. Horsburgh Jr has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: H.E. Jenkins reports grants from the US National Institutes of Health (R01GM122876) during the conduct of the study.

Support statement: This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (K01TW010829 to S.S. Chiang) and (R01GM122876 to H.E. Jenkins). Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.Snow KJ, Sismanidis C, Denholm J, et al. The incidence of tuberculosis among adolescents and young adults: a global estimate. Eur Respir J 2018; 51:1901007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brailey M. Mortality in the children of tuberculous households. Am J Public Health Nations Health 1940; 30: 816–823. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.30.7.816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bentley FJ, Grzybowski S, Benjamin B. Tuberculosis in Childhood and Adolescence: with Special Reference to the Pulmonary Forms of the Disease. London, The National Association for the Prevention of Tuberculosis, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lincoln EM, Sewell EM. Tuberculosis in Children. New York, McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frost WH. The age selection of mortality from tuberculosis in successive decades. 1939. Am J Epidemiol 1995; 141: 4–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weber HC, Beyers N, Gie RP, et al. The clinical and radiological features of tuberculosis in adolescents. Ann Trop Paediatr 2000; 20: 5–10. doi: 10.1080/02724930091995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sant'Anna C, March MF, Barreto M, et al. Pulmonary tuberculosis in adolescents: radiographic features. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2009; 13: 1566–1568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snow KJ, Cruz AT, Seddon JA, et al. Adolescent tuberculosis. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2020; 4: 68–79. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30337-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cruz AT, Hwang KM, Birnbaum GD, et al. Adolescents with tuberculosis: a review of 145 cases. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2013; 32: 937–941. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3182933214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Pontual L, Balu L, Ovetchkine P, et al. Tuberculosis in adolescents: a French retrospective study of 52 cases. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2006; 25: 930–932. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000237919.53123.f4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furin J, Cox H, Pai M. Tuberculosis. Lancet 2019; 393: 1642–1656. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30308-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jenkins HE, Plesca V, Ciobanu A, et al. Assessing spatial heterogeneity of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in a high-burden country. Eur Respir J 2013; 42: 1291–1301. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00111812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skrahina A, Hurevich H, Zalutskaya A, et al. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Belarus: the size of the problem and associated risk factors. Bull World Health Organ 2013; 91: 36–45. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.104588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO Regional Office for Europe. Anti-tuberculosis drug resistance among tuberculosis patients in Ukraine and risk factors for MDR-TB: results of the first national survey, 2013–2014. Copenhagen, World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaaf HS, Garcia-Prats AJ. Diagnosis of the most common forms of extrathoracic tuberculosis in children In: Starke JR, Donald PR, eds. Handbook of Child & Adolescent Tuberculosis. New York, Oxford University Press, 2016; pp. 177–199. [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2019. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ministry of Health of Ukraine. Order of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine No. 1091: On approval and implementation of medical technological documents for the standardization of medical aid for tuberculosis. Kyiv, Ukraine, 2012.

- 18.Ministry of Health of Ukraine. Order of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine No. 620: On approval and implementation of medical technological documents for the standardization of medical aid for tuberculosis. Kyiv, Ukraine, 2014.

- 19.Snow K, Hesseling AC, Naidoo P, et al. Tuberculosis in adolescents and young adults: epidemiology and treatment outcomes in the Western Cape. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2017; 21: 651–657. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.16.0866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mulongeni P, Hermans S, Caldwell J, et al. HIV prevalence and determinants of loss-to-follow-up in adolescents and young adults with tuberculosis in Cape Town. PLoS ONE 2019; 14: e0210937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The dynamics of migration in Ukraine: where the largest number of migrants are registered www.slovoidilo.ua/2019/06/13/infografika/suspilstvo/dynamika-mihracziyi-ukrayini-zareyestrovano-najbilshe-pereselencziv Date last accessed: November 19, 2019.

- 22.World Health Organization. Definitions and Reporting Framework for Tuberculosis - 2013 Revision. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiseman CA, Gie RP, Starke JR, et al. A proposed comprehensive classification of tuberculosis disease severity in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2012; 31: 347–352. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318243e27b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The World Bank. Data: health, nutrition and population statistics: population estimates and projections. Date last accessed: August 30, 2019 datatopics.worldbank.org/hnp/popestimates.

- 25.Shin SS, Keshavjee S, Gelmanova IY, et al. Development of extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis during multidrug-resistant tuberculosis treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 182: 426–432. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200911-1768OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jenkins HE, Crudu V, Soltan V, et al. High risk and rapid appearance of multidrug resistance during tuberculosis treatment in Moldova. Eur Respir J 2014; 43: 1132–1141. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00203613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seddon JA, Chiang SS, Esmail H, et al. The wonder years: what can primary school children teach us about immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis? Front Immunol 2018; 9: 2946. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Odone A, Calderon R, Becerra MC, et al. Acquired and transmitted multidrug resistant tuberculosis: the role of social determinants. PLoS ONE 2016; 11: e0146642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yermachenko A, Dvornyk V. UGT2B4 previously implicated in the risk of breast cancer is associated with menarche timing in Ukrainian females. Gene 2016; 590: 85–89. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2016.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Padyana M, Bhat RV, Dinesha M, et al. HIV-tuberculosis: a study of chest x-ray patterns in relation to CD4 count. N Am J Med Sci 2012; 4: 221–225. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.95904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kistan J, Laher F, Otwombe K, et al. Pulmonary TB: varying radiological presentations in individuals with HIV in Soweto, South Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2017; 111: 132–136. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trx028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gillespie SH. Evolution of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: clinical and molecular perspective. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002; 46: 267–274. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.2.267-274.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drobniewski F, Balabanova Y, Nikolayevsky V, et al. Drug-resistant tuberculosis, clinical virulence, and the dominance of the Beijing strain family in Russia. JAMA 2005; 293: 2726–2731. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.22.2726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feng JY, Su WJ, Liu LY, et al. Radiological presentation of pulmonary tuberculosis infected by the W-Beijing Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2009; 13: 1387–1392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chatterjee A, D'Souza D, Vira T, et al. Strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from western Maharashtra, India, exhibit a high degree of diversity and strain-specific associations with drug resistance, cavitary disease, and treatment failure. J Clin Microbiol 2010; 48: 3593–3599. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00430-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Merker M, Nikolaevskaya E, Kohl TA, et al. Multidrug- and extensively drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing clades, Ukraine, 2015. Emerging Infect Dis 2020; 26: 481–490. doi: 10.3201/eid2603.190525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pavlenko E, Barbova A, Hovhannesyan A, et al. Alarming levels of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Ukraine: results from the first national survey. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2018; 22: 197–205. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.17.0254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Acosta CD, Kaluski DN, Dara M. Conflict and drug-resistant tuberculosis in Ukraine. Lancet 2014; 384: 1500–1501. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61914-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dudnyk A, Rzhepishevska O, Rogach K, et al. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Ukraine at a time of military conflict. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2015; 19: 492–493. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Werf MJ, Chechulin Y, Yegorova OB, et al. Health care seeking behaviour for tuberculosis symptoms in Kiev City, Ukraine. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2006; 10: 390–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheng S, Chen W, Yang Y, et al. Effect of diagnostic and treatment delay on the risk of tuberculosis transmission in Shenzhen, China: an observational cohort study, 1993–2010. PLoS ONE 2013; 8: e67516. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Getnet F, Demissie M, Worku A, et al. Delay in diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis increases the risk of pulmonary cavitation in pastoralist setting of Ethiopia. BMC Pulm Med 2019; 19: 201. doi: 10.1186/s12890-019-0971-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moore BK, Anyalechi E, van der Walt M, et al. Epidemiology of drug-resistant tuberculosis among children and adolescents in South Africa, 2005–2010. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2015; 19: 663–669. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dubrovina I, Miskinis K, Lyepshina S, et al. Drug-resistant tuberculosis and HIV in Ukraine: a threatening convergence of two epidemics? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2008; 12: 756–762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kyselyova G, Martsynovska V, Volokha A, et al. Young people in HIV care in Ukraine: a national survey on characteristics and service provision. F1000Res 2019; 8: 323. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.18573.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]