Abstract

Background

Unintended pregnancy has dire consequences on the health and socioeconomic wellbeing of adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) (aged 15–24 years). While most studies tend to focus on lack of access to contraceptive information and services, and poverty as the main contributing factor to early-unintended pregnancies, the influence of sexual violence has received limited attention. Understanding the link between sexual violence and unintended pregnancy is critical towards developing a multifaceted intervention to reduce unintended pregnancies among AGYW in South Africa, a country with high teenage pregnancy rate. Thus, we estimated the magnitude of unintended pregnancy among AGYW and also examined the effect of sexual violence on unintended pregnancy.

Methods

Our study adopted a cross-sectional design, and data were obtained from AGYW in a South African university between June and November 2018. A final sample of 451 girls aged 17–24 years, selected using stratified sampling, were included in the analysis. We used adjusted and unadjusted logistic regression analysis to examine the effect of sexual violence on unintended pregnancy.

Results

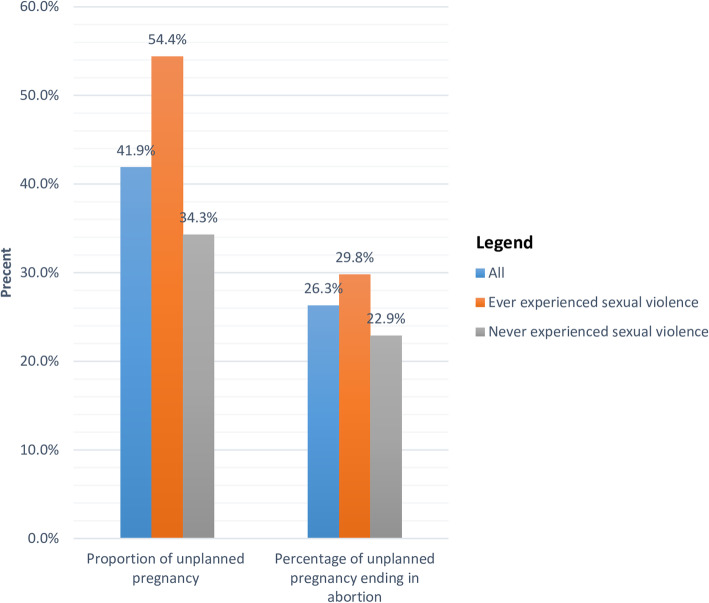

The analysis shows that 41.9% of all respondents had experienced an unintended pregnancy, and 26.3% of those unintended pregnancies ended in abortions. Unintended pregnancy was higher among survivors of sexual violence (54.4%) compared to those who never experienced sexual abuse (34.3%). In the multivariable analysis, sexual violence was consistently and robustly associated with increased odds of having an unintended pregnancy (AOR:1.70; 95% CI: 1.08–2.68).

Conclusion

Our study found a huge magnitude of unintended pregnancy among AGYW. Sexual violence is an important predictor of unintended pregnancy in this age cohort. Thus, addressing unintended pregnancies among AGYW in South Africa requires interventions that not only increase access to contraceptive information and services but also reduce sexual violence and cater for survivors.

Keywords: Unintended pregnancy, Unplanned pregnancy, Survivors, Sexual violence, Contraception, Adolescent and young women, Abortions

Background

Unintended pregnancy, especially among adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) remains a concerning health and social problem in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and worldwide [1, 2]. Between 2010 and 2014, approximately 44.5% of all pregnancies and 23% of births were unintended worldwide [2]. Unintended pregnancy is the main reason for having an abortion [3]. Of the approximately 99 million unintended pregnancies that occur each year, more than half (56%) end in abortion [2]. Unintended pregnancy has deleterious consequences, including a heightened risk of maternal depression [4], and late initiation of antenatal care [5].

Adolescent girls and young women (aged 15–24 years) are at high risk of having an unintended pregnancy because they are far more likely to enter into sexual relationships and also more likely to delay marriage in order to complete school and become better prepared to join the labour force [6]. A study conducted in Uganda shows that sexually active adolescent girls had the highest rate of abortion (76.1 abortions per 1000 women 15–19) of all women within the reproductive age group [7]. Another study in Kenya shows that severe complications of unsafe abortion were most common among adolescent girls [8].

With figures as high as 102.8 pregnant adolescents per 1000 girls aged 15–19 years, SSA has the highest rates of teenage pregnancies in the world [9]. Early unintended pregnancy has dire health and socioeconomic consequences. Globally, pregnancy and childbirth complications are one of the leading causes of death among adolescent girls. Adolescent mothers face an increased risk of perinatal morbidities such as eclampsia, puerperal endometritis, systemic infections, low birth weight, preterm delivery, and severe neonatal conditions [10–12]. Indeed, early adolescent pregnancy has been linked with an increased risk of HIV infection [13]. Furthermore, early childbearing also negatively impacts girls’ socioeconomic development and empowerment, further bolstering the vicious cycle of poverty [14–17].

In South Africa, AGYW continue to get pregnant at alarmingly high rates, with about 28% of girls having begun childbearing by their nineteenth birthday [18]. Contributing factors have been described as multifaceted, and include individual, household, community, and structural factors [19]. At the individual level, the high prevalence of unintended pregnancies has been associated with limited contraceptive knowledge, incorrect and inconsistent contraceptive use, inaccessibility of contraceptives [1, 20–22]. At the household and family level, household poverty, lack of family support, death of parents, lack of communication with parents about sex encounters, and single-parent family structure are associated with early-unintended pregnancies [23–27]. At the community level, community-level poverty, rural residence, cultural norms that foster gender inequality and violence against women are among the factors associated with a higher likelihood of unintended pregnancies [23, 24]. Structural factors associated with the increased level of early unintended pregnancy include restrictive policies - such as laws on age of consent for contraception services, healthcare systems failures, inadequate access to contraception as well as epileptic availability and access to reproductive healthcare services [28, 29].

While several studies have focused on the influence of contraceptive access and poverty on the increased risk of having an unplanned pregnancy [1, 20, 23], the contribution of sexual violence to increased risk of unintended pregnancy particularly among AGYW has received limited attention, with only a few studies from other regions focusing on this link [30–33]. The pathway through which sexual violence could lead to unintended pregnancy is through non-use of contraceptive, underreporting of incidences of sexual violence, and lack of requisite care to address the potential impacts of sexual violence, including unintended pregnancy [34, 35]. Individuals who rape young people are likely not to use condoms, and since the knowledge of emergency contraception is low among AGYW [36, 37], the risk of them having an unintended pregnancy is high. Also, given that victims of sexual violence rarely come forward, the risk of having unintended pregnancy is high as young people are rarely going to know how to prevent pregnancy after exposure to forced and coerced sex.

Several studies have linked sexual violence to increased risk of HIV infection [38, 39], poor mental health outcomes [40, 41], poor self-rated health [41] and non-use of contraceptives [39] among AGYW in South Africa, but sparse attention has been given to the effect of sexual violence and unintended pregnancy. However, studies have examined the link between coerced first sex and unintended pregnancy, reporting contrasting results [13, 42]. Christofides et al. (2014) show that physical abuse is associated with a higher likelihood of unintended pregnancy. But, they found no relationship between coerced first sex and unintended pregnancy in contrast to an earlier study by Maharaj and Munthree (2007). Overall, most studies on unintended pregnancy among AGYW in South Africa focused on the role of gender inequality, socioeconomic inequalities, and lack of contraceptive access and use, with limited attention to the role of sexual violence. As such, the main research question this study examines is: what is the link between sexual violence and unintended pregnancy among AGYW? Our study adds to the growing body of knowledge by determining the magnitude of unintended pregnancies as well as examining the relationship between sexual violence and unintended pregnancies among AGYW in South Africa. The study finding will be useful in developing policies and strategies to improve the sexual and reproductive health outcomes of young people. Specifically, our findings could inform the implementation of youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services in South Africa.

Methods

Study design and setting

The cross-sectional study was conducted among students aged 17–24 years in a South African university located in Eastern Cape province. We selected the university conveniently in a setting with high sexual violence and HIV prevalence [43]. Our focus on AGYW is influenced by the fact that new HIV infection rates were disproportionately high among this cohort in South Africa [44]. University students were recruited because of ease of accessibility and lack of funds for a household survey. The full details of the methodology for the study have been published elsewhere [45, 46]. Only unmarried male and female students aged 15 to 24 years were eligible for the study. Visiting students from another university, married students, and those aged over 24 years were ineligible for selection.

A total of 420 participants were estimated to be the appropriate sample size for this study based on ±5% precision level, a 95% confidence level, and female students’ population of 4000 and 10% possible attrition, using MaCorr Sample Size Calculator. We employed stratified sampling to ensure representativeness. Stratification was based on the following characteristics of students, faculties, and years of study. We drew participants from all faculties based on probability proportionate to the size of the faculty, including social sciences and humanities (n = 138), law (n = 70), health sciences (55), management and commerce (92) and education (155). Students were also stratified by year of study to ensure the final sample is representative of the distribution of study by year of study. We recruited participants from their lecture halls because we were unable to get a comprehensive list of all students.

The study instrument was self-designed and included in Supplementary file 1. Well-trained research assistants administered the survey using ODK collect installed on android devices. The research assistants were postgraduate students and were trained on using the ODK collect application, ethical considerations guiding the research, and participants’ selection. We trained them to select a pre-specified number of students at a particular level and faculty of study. They were instructed to select every tenth student in the classroom and skip participants who refuse to participate. The ODK collect application ensured privacy. Participants were approached and informed about the study purpose. To minimise social desirability bias and further ensure privacy, consenting students completed the survey using either their personal mobile phones or the research assistants’ mobile device in private spaces earmarked for the study on campus. No personal identifying information was collected, and they were shown how to operate the ODK App for android and navigate the survey questions. The study was conducted between June and November 2018. We conducted training of research assistants and pilot testing of study instruments among 30 students using a different university before the study commenced. The response rate was 88% among the female participants included in this study.

The University of Fort Hare ethical review body approved this study (Reference number: GON011). All participants gave written consent indicating that they voluntarily and willingly took part in the study and affirmed that they understood the study purpose, process, and usage of findings. Anonymity and confidentiality of the information provided were ensured throughout the study. We followed all the IRB guidelines for using human subjects in research.

Measures

Our dependent variable is the lifetime experience of unintended pregnancy, which we defined as becoming pregnant at a time a person is not prepared to become pregnant or intended to have children. We measured this by asking participants if they have ever been pregnant when they never wanted to get pregnant. We used a binary response of “yes” or “no” to categorise participants’ responses. We followed the question up by asking what action was taken when they found that they were pregnant. The actions were classified as terminated the pregnancy and carried the pregnancy to term.

Our main independent variable of interest is sexual violence. Sexual violence is defined in this study as any sexual act or attempts to obtain a sexual act by violence or coercion by any person irrespective of their relationship to the victim [47]. We asked respondents if they have ever experienced sexual abuse, such as forced sex or rape and touching of genitals without proper consent. We favoured a narrow definition of sexual violence in this study by excluding verbal sexual assault, which may not lead to unintended pregnancy. Also, we asked if they experienced this sexual abuse before the age of sixteen. The responses were classified as yes or no.

We included three sets of covariates, individual level, behavioural and household, and family level covariates based on existing literature [48–51]. The individual-level covariates include age, religion, and parity. Age was measured as a continuous variable by asking respondents to state their age at their last birthday. We later categorised the ages into late-adolescent girls (17–19 years) and young women (20–24 years). Religiosity was measured by asking participants to rate their level of religiosity out of ten. We classified those who rated themselves 8 to 10 as very religious, those who rated themselves from 5 to 7 as moderately religious, and 1 to 4 as not religious. Lastly, we asked respondents to state how many children they have ever had.

The behavioural factors include recreational drug use and relationship status. We asked participants to indicate if they ever used drugs such as dagga, codeine, cannabis, and/or tramadol for pleasure or to ease tension or stress. Also, we asked respondents if they are single or cohabiting. We classified their responses as yes or no. We included several family/household level factors, including family structure, family support, death of parents, communication of sexual encounters with parents, and parenting type. Family structure was classified as single-parent, polygamous, both parents, and foster family.

Family support was used as a proxy to measure parents’ socioeconomic status. We asked participants to rate the level of support they received from their family as adequate, moderate, insufficient, and no support. Family support relates to financial support and not psychological support. Also, we measured communication with parents regarding sexual encounters by asking respondents if they have ever discussed sex with any or both of their parents. Lastly, we measured parenting style by asking respondents to describe their parents as strict and not strict.

Statistical analysis

The analytical sample of the current paper begins with 510 AGYW, who took part in the survey. From this number, we remove 59 respondents who refused to answer the questions on sexual behaviours, unintended pregnancy, sexual violence, and HIV testing. These sets of participants exercised their right to refuse to answer any questions they feel uncomfortable answering and to drop out of the study at any time. We examined the characteristics of these sets of respondents and did not find any significant difference between them and those included in our analysis. We, therefore, analysed data from 451 AGYW who returned with complete responses representing a response rate of 88.4% among female participants. We performed descriptive statistics of all variables included in this study. We present mean and standard deviation for age. To determine whether sexual violence was associated with a higher likelihood of unintended pregnancy, we fitted two logistic regression models. The first model was a baseline model with no covariates, which was used to estimate the unadjusted odds ratio of the association between the main independent variable and the dependent variables. The second model is a multivariable model, where we included all relevant covariates, including individual, behavioural and family, and household level factors. Alpha level of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Descriptive findings

The average age of respondents was 21.03 (SD: 1.61) years. As shown in Table 1, most respondents were aged 20–24 years (79.6%), single (97.8%), had no children (65.4%), and never drank alcohol (66.5%). Only 38.8% were from a two-parent family. While a majority live their mother (75.4%), only two-fifth of them live with their father. Only a few respondents described their parents as strict (father 30.8%, mother 26.4%). While most of the respondents have discussed sex with their mother (61.6%), only a few of them have talked about sex with their father (10.4%). Over a third of the respondents (37.9%) have ever experienced sexual violence, and 17.7% did before the age of 16.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic, behavioural and household characteristics of respondents

| Variable | Frequency | Percentages |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 17–19 | 92 | 20.4 |

| 20–24 | 359 | 79.6 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Single | 441 | 97.8 |

| Cohabiting | 10 | 2.2 |

| Parity | ||

| None | 295 | 65.4 |

| One | 150 | 33.3 |

| More than one | 6 | 1.3 |

| Family support | ||

| Adequate | 168 | 37.3 |

| Moderate | 202 | 44.8 |

| Insufficient support | 81 | 18.0 |

| Religiosity rating | ||

| Not religious | 139 | 32.0 |

| Moderately religious | 197 | 45.4 |

| Very religious | 98 | 22.6 |

| Family structure | ||

| Two parents family | 175 | 38.8 |

| Single parent family | 196 | 43.5 |

| Living with grandparents | 49 | 10.9 |

| Living with foster parents | 31 | 6.9 |

| Mother alive | 377 | 83.6 |

| Father alive | 282 | 62.5 |

| Live with dad | 190 | 42.1 |

| Live with mum | 340 | 75.4 |

| Talk sex to dad | 47 | 10.4 |

| Talk sex to mum | 278 | 61.6 |

| Strict father | 139 | 30.8 |

| Strict mother | 119 | 26.4 |

| Ever drank alcohol | 300 | 66.5 |

| Current alcohol users | 201 | 44.6 |

| Drank alcohol last week | 108 | 23.9 |

| Ever used drugs | 138 | 30.6 |

| Currently use drugs | 51 | 11.3 |

| Lifetime experience of sexual abuse | 171 | 37.9 |

| Past year experience of sexual abuse | 114 | 25.3 |

| Childhood sexual abuse | 80 | 17.7 |

As presented in Fig. 1, 41.9% of all respondents had experienced an unintended pregnancy, and 26.3% of those unintended pregnancies ended in abortions. Unintended pregnancy was higher among young women (20–24 years) (47.1%), those who received no or insufficient support (58.0%), those who rated themselves not religious (54.7%), those who had ever consumed alcohol (48%), and survival of sexual violence (54.4%) compared to adolescent girls (21.7%), those who received adequate support (33.9%), those that rated themselves as very religious (30.6%), those who never drank alcohol (29.8%), and those never experienced sexual assault (34.3%) respectively (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Unintended pregnancy and related abortion among adolescent and young women

Table 2.

Chi-square statistics showing factors associated with having had an unintended pregnancy

| Variables | Never had an unintended pregnancy | Ever had an unintended pregnancy | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime experience of sexual abuse | |||

| Yes | 78 (45.6) | 93 (54.4) | < 0.001 |

| No | 184 (65.7) | 96 (34.3) | |

| Age | |||

| 17–19 | 72 (78.3) | 20 (21.7) | < 0.001 |

| 20–24 | 190 (52.9) | 169 (47.1) | |

| Family support | |||

| Adequate | 111 (66.1) | 57 (33.9) | 0.001 |

| Moderate | 117 (57.9) | 85 (42.1) | |

| No or insufficient support | 34 (42.0) | 47 (58.0) | |

| Family structure | |||

| Two parents family | 106 (54.1) | 90 (45.9) | 0.304 |

| Single parent family | 109 (62.3) | 66 (37.7) | |

| Living with grand parents | 31 (63.3) | 18 (36.7) | |

| Living with foster parents | 16 (51.6) | 15 (48.4) | |

| Religiosity rating | |||

| Not religious | 63 (45.3) | 76 (54.7) | < 0.001 |

| Moderately religious | 123 (62.4) | 74 (37.6) | |

| Very religious | 68 (69.4) | 30 (30.6) | |

| Parity | |||

| None | 248 (84.1) | 47 (15.9) | < 0.001 |

| At least one | 14 (9.0) | 142 (91.0) | |

| Ever drank alcohol | |||

| Yes | 156 (52.0) | 144 (48.0) | < 0.001 |

| No | 106 (70.2) | 45 (29.8) | |

| Ever used drugs for recreational purposes | |||

| Yes | 70 (50.7) | 68 (49.3) | 0.023 |

| No | 192 (61.3) | 121 (38.7) | |

| Life time experience of sexual abuse | |||

| Yes | 49 (43.0) | 65 (57.0) | < 0.001 |

| No | 213 (63.2) | 124 (36.8) | |

| Strict father | |||

| Yes | 81 (68.1) | 38 (31.9) | 0.007 |

| No | 181 (54.5) | 151 (45.5) | |

| Strict mother | |||

| Yes | 91 (65.5) | 48 (34.5) | 0.021 |

| No | 171 (54.8) | 141 (45.2) | |

| Sex talk with father | |||

| Yes | 35 (74.5) | 12 (25.5) | 0.011 |

| No | 227 (56.2) | 177 (43.8) | |

| Sex talk with mother | |||

| Yes | 153 (55.0) | 125 (45.0) | 0.058 |

| No | 109 (63.0) | 64 (37.0) | |

Multivariable findings

As shown in Model 1, sexual violence was associated with higher odds of having an unintended pregnancy (Table 3). In Model 2, we included individual, behavioural and family, and household-level covariates. After adjusting for all covariates, the magnitude of the effect reduced, but the direction of effect persists, showing that when adolescents and young adults reported having experienced sexual violence, they are more likely to have also had an unintended pregnancy. Alcohol use and increasing age were also significantly associated with a lifetime experience of unintended pregnancy. However, family structure, family support, religiosity, and parenting style were not significantly associated with unintended pregnancy.

Table 3.

Logistic regression models of the association between sexual violence and unintended pregnancy

| Variables | Unadjusted model | Adjusted model |

|---|---|---|

| Life experience of sexual abuse | ||

| Yes | 2.29 (1.55–3.37)*** | 1.70 (1.08–2.68)* |

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Age | ||

| 20–24 | 3.29 (1.83–5.93)*** | |

| 17–19 | 1 | |

| Family support | ||

| Adequate | 0.71 (0.39–1.30) | |

| Moderate | 0.65 (0.34–1.24) | |

| No or insufficient support | 1 | |

| Family structure | ||

| Two parents family | 0.92 (0.36–2.37) | |

| Single parent family | 0.89 (0.33–2.40) | |

| Living with grand parents | 0.79 (0.36–2.37) | |

| Living with foster parents | 1 | |

| Religiosity rating | ||

| Poor | 1.76 (0.96–3.23) | |

| Average | 1.09 (0.62–1.90) | |

| Good | 1 | |

| Ever drank alcohol | ||

| Yes | 1.68 (1.03–2.73)* | |

| No | 1 | |

| Ever used drugs for recreational purposes | ||

| Yes | 0.94 (0.58–1.54) | |

| No | 1 | |

| Strict father | ||

| Yes | 0.64 (0.37–1.10) | |

| No | 1 | |

| Strict mother | ||

| Yes | 0.66 (0.41–1.04) | |

| No | 1 | |

| Sex talk with father | ||

| Yes | 0.68 (0.32–1.45) | |

| No | 1 | |

| Sex talk with mother | ||

| Yes | 1.26 (0.75–2.12) | |

| No | 1 | |

*pvalues <0.05 ***pvalues <0.001

Discussion of findings

This study examines the relationship between sexual violence and unintended pregnancies among AGYW in South Africa. We found a high prevalence of unintended pregnancy (41.5%) among AGYW in our study setting, with a quarter of all unintended pregnancies resulting in abortions. Over 91% of pregnancies among AGYW are unintended in our study cohort. Our findings further add to the growing body of knowledge, showing a high prevalence of unintended pregnancy among AGYW in South Africa. Underuse of contraceptives has been attributed to the high rate of unintended pregnancy among AGYW in SSA [20]. Thus, addressing unintended pregnancy among AGYW in South Africa will require increasing access to contraceptive information and services.

Our result, consistent with previous studies [30–33], demonstrates clear, consistent, and robust evidence supporting our proposition that AGYW with lived experiences of sexual violence (AOR:1.76, 95% CI:1.07–2.90) are more likely to report unintended pregnancies. The pathway through which sexual violence could lead to unintended pregnancy is through non-use of contraceptive, underreporting of incidences of sexual violence, and lack of requisite care to address the potential impacts of sexual violence, including unintended pregnancy. It is clear from extant studies that most victims of sexual violence do not officially report rape incidence or even mention it to other people [34]. Lack of reporting of sexual violence incidences may mean survivors will not receive the necessary care needed. Also, it is well established that most perpetrators of sexual violence are close to the survivors, with friends and boyfriends being the most likely culprits, making the incidence more frequent and the consequences severe [35]. For example, the prevalence of forced sexual initiation ranges from 4 to 31% [40]. AGYW are also at a disadvantage because they have low knowledge of after sex contraception [36, 37], implying that if they fail to report or seek care, their risk of unintended pregnancy increases.

Given that early-unintended pregnancies worsen the socioeconomic outcomes of AGYW [14–17], there is a need for research that examines how sexual violence against women could worsen gender inequalities and female poverty. Aside from providing access to contraceptive information and services, there is a need for holistic efforts to expand young people’s knowledge and awareness around female sexual and reproductive health rights. Furthermore, it is vital that sex education, which highlights the damaging effects of sexual violence, discourages hegemonic masculinity, and encourages responsible sexual decision making, be included in schools’ curriculums, and be made an integral part of religious/community body events to ensure that out-of-school children are not left out. Parents, caregivers, and guardians should additionally assume the responsibilities of teaching these important lessons at home. As social pressure or fear of stigma may mean that sexual violence cases are underreported, it is crucial that responsible authorities launch appropriate investigations when cases of sexual assaults are reported, and ensure justice served accordingly in addition to providing judgment-free victim support, which will encourage other victims to speak up.

Strength and limitations

Our study provides needed evidence on the link between sexual violence and unintended, which could provide the basis for future studies and intervention to tackle sexual violence and unintended pregnancy among AGYW in South Africa and beyond. However, our study is not without limitations. The use of cross-sectional data means causal inference could not be drawn between sexual violence and unintended pregnancy. Also, underreporting of unintended pregnancy and sexual violence could not be ruled out given the sensitive nature of the topic. However, the use of ODK collect for android offers privacy for participants, thereby limiting the effect of social desirability bias. Also, our use of secondary dataset means that our study did not include all potential confounding factors, including knowledge of emergency contraception and access to emergency contraception. Lastly, our focus on university students may not adequately portray a real-world situation for the target age bracket, and thus limits our study’s generalizability. University students are generally more educated compared with the general population of AGYW. Also, our study is limited to only unmarried AGYW; as such, the findings are not generalizable to married AGYW.

Conclusions

Consistent with previous research in sub-Saharan Africa, our study found a high prevalence of unintended pregnancy among adolescents and young women, suggesting that despite improved access to contraceptives in South Africa, the magnitude of unintended pregnancy remains high. We also found that sexual violence is associated with a higher likelihood of unintended pregnancy. As such, addressing unintended pregnancies among AGYW in South Africa requires interventions that not only increase access to contraceptive information and services but also reduce sexual violence and cater for survivors. Future studies should examine the link between sexual violence and unintended pregnancy among out of school girls as well as the potential link between exposure to sexual violence and gender inequality and female poverty.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgments

We express our profound gratitude to our study participants and research assistants for their generous contributions to this study.

Abbreviations

- AGYW

Adolescent girls and young women

- SSA

Sub-Saharan Africa

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

Authors’ contributions

AIA conceptualised the study, managed the data collection, and perform the statistical analysis. HCE and AIA contributed to drafting the manuscript. All authors revised and approved the final draft.

Funding

We did not obtain any specific funding for this study.

Availability of data and materials

The data analysed will be made available by the corresponding author upon request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The University of Fort Hare’s ethical review body approved this study (Reference number: GON011). All participants gave written consent, indicating that they voluntarily and willingly took part in the study and affirmed that they understood the study purpose, process, and usage of findings. Anonymity and confidentiality of the information provided were ensured throughout the study. We followed all the IRB guidelines for using human subjects in research.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The first author is an associate editor at BMC Public Health. The second author has no competing interests to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Anthony Idowu Ajayi, Email: ajayianthony@gmail.com.

Henrietta Chinelo Ezegbe, Email: hettie103@gmail.com.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12889-020-09488-6.

References

- 1.Mchunu G, Peltzer K, Tutshana B, Seutlwadi L. Adolescent pregnancy and associated factors in south African youth. Afr Health Sci. 2012;12(4):426–434. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v12i4.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bearak J, Popinchalk A, Alkema L, Sedgh G. Global, regional, and subregional trends in unintended pregnancy and its outcomes from 1990 to 2014: estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(4):e380–e389. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30029-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taft AJ, Shankar M, Black KI, Mazza D, Hussainy S, Lucke JC. Unintended and unwanted pregnancy in Australia: a cross-sectional, national random telephone survey of prevalence and outcomes. Med J Aust. 2018;209(9):407–408. doi: 10.5694/mja17.01094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faisal-Cury A, Menezes PR, Quayle J, Matijasevich A. Unplanned pregnancy and risk of maternal depression: secondary data analysis from a prospective pregnancy cohort. Psychol Health Med. 2017;22(1):65–74. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2016.1153678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Exavery A, Kanté AM, Hingora A, Mbaruku G, Pemba S, Phillips JF. How mistimed and unwanted pregnancies affect timing of antenatal care initiation in three districts in Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13(1):35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh S, Remez L, Sedgh G, Kwok L, Onda T. Abortion worldwide 2017: uneven Progress and unequal access. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sully EA, Atuyambe L, Bukenya J, Whitehead HS, Blades N, Bankole A. Estimating abortion incidence among adolescents and differences in postabortion care by age: a cross-sectional study of postabortion care patients in Uganda. Contraception. 2018;98(6):510–516. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2018.07.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Izugbara C, Kimani E, Mutua M, Mohamed S, Ziraba A, Egesa C, Gebreselassie H, Levandowski B, Singh S, Bankole A. Incidence and complications of unsafe abortion in Kenya: key findings of a national study. Nairobi, Kenya: African Population and Health Research Center, Ministry of Health, Kenya, Ipas, and Guttmacher Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.United Nations DoEaSA, Population Division . World Population Prospects: the 2017 Revision. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO . Global health estimates 2015: deaths by cause, age, sex, by country and by region, 2000–2015. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grønvik T, Sandøy IF. Complications associated with adolescent childbearing in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0204327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jonas K, Crutzen R, van den Borne B, Sewpaul R, Reddy P. Teenage pregnancy rates and associations with other health risk behaviours: a three-wave cross-sectional study among south African school-going adolescents. Reprod Health. 2016;13(1):50. doi: 10.1186/s12978-016-0170-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christofides NJ, Jewkes RK, Dunkle KL, Nduna M, Shai NJ, Sterk C. Early adolescent pregnancy increases risk of incident HIV infection in the eastern cape, South Africa: a longitudinal study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17(1):18585. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.18585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yazdkhasti M, Pourreza A, Pirak A, Abdi F. Unintended pregnancy and its adverse social and economic consequences on health system: a narrative review article. Iran J Public Health. 2015;44(1):12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korenman S, Fales S. The socioeconomic effects of teenage childbearing: a review of the recent literature. New York City: Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faisal-Cury A, Tabb KM, Niciunovas G, Cunningham C, Menezes PR, Huang H. Lower education among low-income Brazilian adolescent females is associated with planned pregnancies. Int J Women's Health. 2017;9:43. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S118911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee D. The early socioeconomic effects of teenage childbearing: a propensity score matching approach. Demogr Res. 2010;23:697–736. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Health NDo, Africa SS, Council SAMR, ICF . South Africa Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Pretoria, South Africa, and Rockville: NDoH, Stats SA, SAMRC, and ICF; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kilanowski JF. Breadth of the socio-ecological model. Am Psychol. 2017;32:513–531. doi: 10.1080/1059924X.2017.1358971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bellizzi S, Pichierri G, Menchini L, Barry J, Sotgiu G, Bassat Q. The impact of underuse of modern methods of contraception among adolescents with unintended pregnancies in 12 low-and middle-income countries. J Glob Health. 2019;9(2):020429. doi: 10.7189/jogh.09.020429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chanda MM, Ortblad KF, Mwale M, Chongo S, Kanchele C, Kamungoma N, Barresi LG, Harling G, Bärnighausen T, Oldenburg CE. Contraceptive use and unplanned pregnancy among female sex workers in Zambia. Contraception. 2017;96(3):196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sutton MY, Zhou W, Frazier EL. Unplanned pregnancies and contraceptive use among HIV-positive women in care. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0197216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lambani MN. Poverty the cause of teenage pregnancy in Thulamela municipality. J Sociology Social Anthropol. 2015;6(2):171–176. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Izugbara CO, Ochako R, Izugbara C. Gender scripts and unwanted pregnancy among urban Kenyan women. Culture, Health Sexuality. 2011;13(9):1031–1045. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.598947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Odimegwu C, Mkwananzi S. Factors associated with teen pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa: a multi-country cross-sectional study. Afr J Reprod Health. 2016;20(3):94–107. doi: 10.29063/ajrh2016/v20i3.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thobejane TD. Factors contributing to teenage pregnancy in South Africa: the case of Matjitjileng Village. J Sociology Social Anthropol. 2015;6(2):273–277. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mushwana L, Monareng L, Richter S, Muller H. Factors influencing the adolescent pregnancy rate in the greater Giyani municipality, Limpopo Province–South Africa. Int J Africa Nurs Sci. 2015;2:10–18. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yarrow E, Anderson K, Apland K, Watson K. Can a restrictive law serve a protective purpose? The impact of age-restrictive laws on young people’s access to sexual and reproductive health services. Reprod Health Matters. 2014;22(44):148–156. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(14)44809-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mbeba RM, Mkuye MS, Magembe GE, Yotham WL, Obeidy Mellah A, Mkuwa SB. Barriers to sexual reproductive health services and rights among young people in Mtwara district, Tanzania: a qualitative study. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;13(Suppl 1):13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Acharya K, Paudel YR, Silwal P. Sexual violence as a predictor of unintended pregnancy among married young women: evidence from the 2016 Nepal demographic and health survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):196. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2342-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cripe SM, Sanchez SE, Perales MT, Lam N, Garcia P, Williams MA. Association of intimate partner physical and sexual violence with unintended pregnancy among pregnant women in Peru. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2008;100(2):104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gomez AM. Sexual violence as a predictor of unintended pregnancy, contraceptive use, and unmet need among female youth in Colombia. J Women's Health. 2011;20(9):1349–1356. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller E, Jordan B, Levenson R, Silverman JG. Reproductive coercion: connecting the dots between partner violence and unintended pregnancy. Contraception. 2010;81(6):457–459. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Machisa M, Jewkes R, Morna C, Rama K. The war at home: Gender based violence indicators project. In: Gauteng research report. Johannesburg: Gender Links & South African Medical Research Council; 2011:1–16.

- 35.Krebs CP, Lindquist CH, Warner TD, Fisher BS, Martin SL. Campus sexual assault (CSA) study, final report (2007) 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ajayi AI, Nwokocha EE, Adeniyi OV, Goon D, Akpan W. Unplanned pregnancy-risks and use of emergency contraception: a survey of two Nigerian universities. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):382. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2328-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ajayi AI, Nwokocha EE, Akpan W, Adeniyi OV. Use of non-emergency contraceptive pills and concoctions as emergency contraception among Nigerian University students: results of a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1046. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3707-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pitpitan EV, Kalichman SC, Eaton LA, Sikkema KJ, Watt MH, Skinner D. Gender-based violence and HIV sexual risk behavior: alcohol use and mental health problems as mediators among women in drinking venues, Cape Town. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(8):1417–1425. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Speizer IS, Pettifor A, Cummings S, MacPhail C, Kleinschmidt I, Rees HV. Sexual violence and reproductive health outcomes among south African female youths: a contextual analysis. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(S2):S425–S431. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.136606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stockman JK, Lucea MB, Campbell JC. Forced sexual initiation, sexual intimate partner violence and HIV risk in women: a global review of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(3):832–847. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0361-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Decker MR, Peitzmeier S, Olumide A, Acharya R, Ojengbede O, Covarrubias L, Gao E, Cheng Y, Delany-Moretlwe S, Brahmbhatt H. Prevalence and health impact of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence among female adolescents aged 15–19 years in vulnerable urban environments: a multi-country study. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(6):S58–S67. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maharaj P, Munthree C. Coerced first sexual intercourse and selected reproductive health outcomes among young women in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Biosoc Sci. 2007;39(2):231. doi: 10.1017/S0021932006001325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zuma K, Shisana O, Rehle TM, Simbayi LC, Jooste S, Zungu N, Labadarios D, Onoya D, Evans M, Moyo S. New insights into HIV epidemic in South Africa: key findings from the national HIV prevalence, incidence and behaviour survey, 2012. Afr J AIDS Res. 2016;15(1):67–75. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2016.1153491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.UNICEF: Turning the tide against AIDS will require more concentrated focus on adolescents and young people. UNICEF data; 2020 [https://data.unicef.org/topic/hivaids/adolescents-young-people/]. Accessed 24 Apr 2020.

- 45.Ajayi A, Mudefi E, Adeniyi O, Goon D. Achieving the first of the joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 90-90-90 targets: understanding the influence of HIV risk perceptions, knowing one’s partner’s status and discussion of HIV/sexually transmitted infections with a sexual partner on uptake of HIV testing. Int Health. 2019;11(6):425–431. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihz056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ajayi AI, Mudefi E, Yusuf MS, Adeniyi OV, Rala N, Ter Goon D. Low awareness and use of pre-exposure prophylaxis among adolescents and young adults in high HIV and sexual violence prevalence settings. Medicine. 2019;98(43):e17716. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000017716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.World Health Organization. Understanding and addressing violence against women: intimate partner violence. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012.

- 48.Ikamari L, Izugbara C, Ochako R. Prevalence and determinants of unintended pregnancy among women in Nairobi, Kenya. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13(1):69. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kassa GM, Arowojolu A, Odukogbe A, Yalew AW. Prevalence and determinants of adolescent pregnancy in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):195. doi: 10.1186/s12978-018-0640-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ameyaw EK, Budu E, Sambah F, Baatiema L, Appiah F, Seidu A-A, Ahinkorah BO. Prevalence and determinants of unintended pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa: a multi-country analysis of demographic and health surveys. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0220970. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bain LE, Zweekhorst MB, de Cock Buning T. Prevalence and Determinants of Unintended Pregnancy in Sub–Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. Afr J Reprod Health. 2020;24(2):187–205. doi: 10.29063/ajrh2020/v24i2.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data analysed will be made available by the corresponding author upon request.