Abstract

The vascular system is a hierarchically organized network of blood vessels that play crucial roles in embryogenesis, homeostasis and disease. Blood vessels are built by endothelial cells – the cells lining the interior of blood vessels – through a process named vascular morphogenesis. Endothelial cells react to different biomechanical signals in their environment by adjusting their behavior to: (1) invade, proliferate and fuse to form new vessels (angiogenesis); (2) remodel, regress and establish a hierarchy in the network (patterning); and (3) maintain network stability (quiescence). Each step involves the coordination of endothelial cell differentiation, proliferation, polarity, migration, rearrangements and shape changes to ensure network integrity and an efficient barrier between blood and tissues. In this review, we highlighted the relevance and the mechanisms involving endothelial cell migration during different steps of vascular morphogenesis. We further present evidence on how impaired endothelial cell dynamics can contribute to pathology.

Keywords: angiogenesis, vascular disease, vascular remodelling, cell migration, cell polarity

Vasculogenesis, angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis

Delivery of oxygen and nutrients to organs alongside with removal of metabolic waste products and carbon dioxide from tissues in vertebrates is mediated by blood and lymphatic vasculatures – two hierarchically branched tubular networks built by endothelial cells (ECs) (1, 2). The blood vasculature is a closed circulatory system organized in arteries, veins and interconnecting capillaries, in which blood recirculates. The lymphatic vasculature is composed of blind-ended lymphatic capillaries, collecting lymphatic vessels and lymph nodes, in which lymph flows unidirectionally. It regulates tissue hydrostatic pressure, lipid absorption and immune cell trafficking. Both vasculatures are physically connected via the lymphatic thoracic duct, where lymph returns macromolecules and extravasated fluid to the blood circulation.

Blood vessels arise during early embryonic development. De novo formation of blood vessels – vasculogenesis – is achieved through differentiation of mesoderm-derived progenitors (angioblasts) into ECs, which aggregate and fuse to form blood islands and the primary capillary plexus (3, 4). This process generates early major vessels, including dorsal aorta, cardinal vein, cranial vessels and the pharyngeal arch arteries (5, 6). The subsequent progressive expansion and remodeling of this primitive network is accomplished mainly by a different process called angiogenesis. Angiogenesis defines the formation of new blood vessels from pre-existing ones and has been described to occur by two distinct mechanisms: sprouting angiogenesis and intussusceptive angiogenesis. Intussusceptive angiogenesis is a process of microvascular growth through the splitting of an existing vessel in two. This process is achieved by insertion of a cellular pillar into a vascular lumen. It was first described in neonatal rats and, although it occurs in regions of the vascular network with minimal hemodynamic forces, it seems that is not dependent on EC migration, relying rather on cell proliferation and cell rearrangements (7, 8).

Sprouting angiogenesis is characterized by the specification of EC phenotypes – endothelial tip and stalk cells – that form new vessels in response to pro-angiogenic stimuli, such as chemokines and growth factors (e.g. vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA)) (1). Tip cells are highly polarized pro-invasive cells that are responsible for guiding the growth of new vascular sprouts. Adjacent to tip cells, stalk cells proliferate and contribute to sprout extension, ensuring the connection to the main vessel (1, 3). Sprouting angiogenesis also originates a primitive vascular plexus that subsequently remodels in order to form a functional hierarchically organized vascular network, composed of arteries, veins and capillaries, in a process called vascular patterning (1). In adult organisms, although most of the blood vessels remain quiescent, angiogenesis still occurs and has a crucial role during several physiological as well as pathological scenarios, such as tissue regeneration, wound healing and cancer development (9).

In this review, we discuss the importance of EC migration during the process of sprouting angiogenesis and vascular patterning, both in physiological and pathological conditions. For further information on the role of cell migration in lymphatic development, we refer the reader for other reviews (2, 10).

General concepts of cell migration

The mechanism of cell migration involves the coordination between forces generated by the dynamics of the actin cytoskeleton and forces exerted on cell’s substrate and cell–cell interfaces by protein complexes. The actin cytoskeleton is regulated by a large number of proteins that are involved in nucleation, elongation, severing and cross-linking of actin polymers comprehensively reviewed in Pollard (2016) (11). Actin filaments can be assembled either in linear filaments or in branched networks in processes driven by distinct protein complexes. Actin-related proteins 2/3 (ARP2/3) complex drives polymerization of branched actin filaments that promotes lamellipodia formation (12, 13). Formins promote linear actin polymerization, typical of filopodia (14). Non-muscle myosin II (NM-MII) is a motor protein that cross-links to and exerts contractile forces on actin filaments (15). Cells attach to the extracellular matrix (ECM) through focal adhesions – integrin-containing protein complexes. Integrins are heterodimeric transmembrane receptors formed by an α and a β subunit, which bind to specific ECM proteins (16). Focal adhesion complexes, bound to the substrate, transmit contractile actomyosin forces to the ECM, establishing traction forces that drive locomotion, in a model described as the molecular clutch model (17). To allow forward movement of the whole cell, focal adhesions are dynamically forming at the front and disassembling at the rear of the cell (18, 19).

Cells use different modes of migration adapted to their environment. Those modes can be classified as mesenchymal, amoeboid or lobopodial (20). The mode of migration is characterized by the type of cellular protrusions that cells form, which are directly linked to the architecture and contractility status of the actin network (20). ECs preferentially use the mesenchymal mode to migrate during angiogenesis (21), which relies on lamellipodia type of protrusions (20). Effective migration requires persistent movement in response to external stimuli. Cells can respond to a wide range of directional stimulus that can be classified into: chemotaxis, if guided by soluble biologically active chemicals; haptotaxis, if guided by a gradient of immobilized ligands on the ECM; mechanotaxis, if guided by mechanical forces (e.g. the effect of fluid shear stress in ECs); and electrotaxis, if guided by electric fields (22, 23). The directional migratory stimulus triggers local activation of signaling pathways that results in the polarization of cell, generating a front and a rear end of the cell. One of the first molecules that shows a polarized distribution is the phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-triphosphate (PIP3). PIP3 accumulates at the front of the cell due to activation of PI3-kinase (PI3K) by RHOA. PIP3 activates guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) that, in turn, activate small GTPases of the RHO family (CDC42, RAC and RHO) (24, 25, 26). RHO GTPases exert their functions by regulating actin and microtubule cytoskeletons. RAC GTPases and CDC42 are active at the leading edge and regulate the formation of cell protrusions, such as filopodia and lamellipodia, promoting directional movement (21, 27, 28, 29, 30). CDC42 also regulates the localization of the microtubule organization center (MTOC) and Golgi apparatus toward the cell’s front. This polarity contributes to asymmetric delivery of membranes and several associated proteins between front and rear ends of the cell, which is thought to contribute to cell migration persistence (19, 31, 32). At the same time, at the rear of the cell, RHOA-dependent activity promotes actomyosin contraction and facilitates rear retraction and force transmission to the substrate (33). During several biological processes, cells migrate collectively as sheets or clusters, instead of as single cells. Collective cell migration is characterized by an emergent population-level behavior that relies on the communication between migrating neighboring cells (19, 34). This behavior arises by mechanically coupling cadherin-based adhesion and actomyosin-based contraction at the population level, which maintains the integrity of the cell cluster (35, 36, 37). Hierarchical organization of migrating cell clusters is essential for efficient migration. This is established by selecting a population of leaders that sense the mechanical and chemical cues that trigger migration. Then, leader cells transmit information to follower cells via mechanical coupling (19, 38). However, it is important to note that our current understanding of the molecular mechanisms of cell migration and invasion, including for ECs, rely mostly on 2D and 3D in vitro data and that in vivo migratory behaviors often use different modes of migration (20).

Cell migration in vasculogenesis and angiogenesis

In vasculogenesis, angioblasts show properties of individually migrating cells and several cell-autonomous and extrinsic signals control their migratory behavior. Fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) and bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) are crucial for the regulation of mesodermal specification and for angioblast differentiation into ECs, while VEGFA appears to have a primary role in both angioblasts and EC migration and proliferation (4). For instance, sonic hedgehog (SHH) controls VEGFA expression, which acts as a chemoattractant and induces the directed migration of single angioblasts from the lateral plate mesoderm to the midline, where they assemble and form the primitive paired dorsal aortas (39, 40). Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) is mainly expressed in angioblasts, and the VEGFA-VEGFR2 signaling axis is crucial for angioblast migration in mouse and Xenopus laevis (39, 41, 42, 43). However, in zebrafish, VEGFA signaling was associated to the proliferation of angioblasts rather than to their migration. Instead, angioblasts rely on Elabela and Apelin activation of the Apelin receptor (Aplnr) signaling and on EC-specific chemotaxis receptor (Ecscr) in order to migrate to the midline (44, 45). Interestingly, Ecscr KO or Aplnr KO mouse models are viable and fertile (46, 47), indicative of significant differences in angioblast migration between mouse and zebrafish. Somite-derived Semaphorin3a1 (SEMA3A1) signals through its receptor, Neuropilin1a (NRP1A), were also associated with guidance and migration of angioblasts to the midline (48). Yet, in the chicken cornea, SEMA3A acts as a repulsive cue during angioblast migration by inhibiting VEGF-induced angioblast migration (49). Thus, these data suggest that SEMA3A can have both repellent and attractant functions during angioblast migration. The intrinsic ability of angioblasts to migrate is also crucial for the establishment of arterial and venous components of the subintestinal plexus. Here, angioblasts residing in the floor of the posterior cardinal vein are able to expand and migrate in response to BMP and VEGFA (50).

Following vasculogenesis, the vascular network actively increases due to EC migration, through sprouting angiogenesis, in order to follow and supply embryonic and organ development. During sprouting angiogenesis, tip cells are pro-invasive ECs that extend numerous filopodia protrusions and guide the nascent vascular sprout. Stalk cells proliferate extensively to foster sprout extension and to ensure the connection to the mother vessel (51). VEGFA-VEGFR2 signaling, via FOXC and MEF2 transcription factors, together with WNT/β-catenin signaling, via SOX17, promotes Delta-like-4 (DLL4) expression in tip cells (52, 53, 54). DLL4 expression in tip cells activates NOTCH1 receptor in adjacent stalk cells in order to laterally inhibit the tip cell phenotype (55, 56, 57, 58). In stalk cells, NOTCH activation leads to a decrease in VEGFR2 and VEGFR3 expression and an increase in the expression of VEGFR1, which, overall, renders stalk cells less responsive to VEGFA. Decreased levels of DLL4 or inhibition of NOTCH signaling produces an excessive number of tip cells, leading to a non-functional increase of sprouting, branching and fusion of blood vessels (55, 56, 57, 58). Interestingly, the phenotypic specialization of ECs as tip or stalk cells is reversible and depends on levels of NOTCH and VEGFA signaling pathways (58, 59, 60). However, recent research suggested that, depending on the context, tip or stalk cell states are more stable and do not switch frequently (61, 62) or can be partially controlled by asymmetric cell division (63).

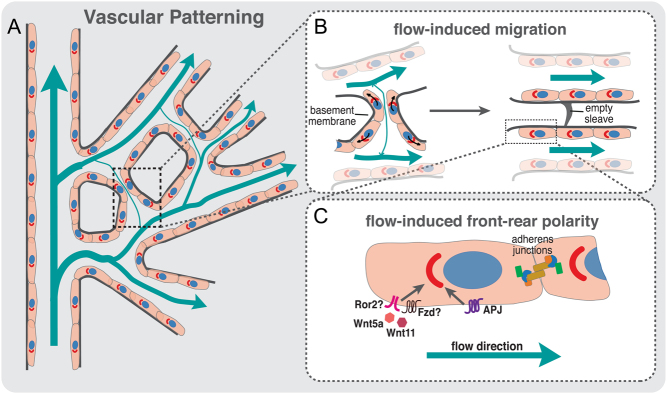

As for the other essential processes in angiogenesis, VEGFA plays a central role in migration. Downstream of VEGFR2 activation, the adaptor proteins NCK1/2 and the RHO GTPase CDC42 regulate EC front-rear polarity of tip cells (64, 65). EC front-rear polarity is also controlled by CAMSAP2, which protects non-centrosomal microtubules and positively regulates sprouting of ECs (66). CDC42 is also fundamental for EC migration and filopodia formation. In mouse, CDC42 regulates filopodia in endothelial tip cells and EC migration, and its inactivation in ECs leads to severe defective angiogenesis in vivo (65, 67). In zebrafish, Cdc42 also controls filopodia formation and tip cell migration via activation of the formin Fmnl3, downstream of BMP and Bmp2r and Alk2/3 receptors (Fig. 1) (68, 69). Interestingly, and contrary to the essential role of Cdc42, genetic deletion of Rac1 or RhoA leads to much milder phenotypes in vivo. RAC1 was shown to be important for EC migration and sprouting in vitro (70, 71); however, Rac1 EC-specific KO only slightly delayed EC migration in vivo (71). Similarly, RHOA was shown to be crucial for EC migration in vitro (72, 73) but is dispensable for physiological angiogenesis in mice in vivo (73). This suggests that EC migration is regulated by additional members of RHO GTPases related to RHOA and RAC1. In accordance, Rho b null mice showed a delay in retinal vascular development (74). Moreover, RHOJ, an EC-enriched small RHO GTPase, was shown to be important for the integration of VEGF and SEMA3E signals, controlling EC migration in vitro, while affecting mildly sprouting angiogenesis in the mouse retina (75, 76). Investigating redundancies between different RHO GTPases could provide further information on the mechanisms fine-tuning EC migratory behavior in vivo.

Figure 1.

Endothelial cell migration during sprouting angiogenesis. Schematic representation of a sprouting front of a vascular plexus with details of a tip cell (in blue) and stalk cells (in red). VEGF/VEGFR2 and BMP/ALK2/3/BMP2R are critical for activation of RHO GTPases, such as CDC42, that controls actin polymerization through formins, such as FMNL3, regulating filopodia and lamellipodia formation. Moreover, VEGF/VEGFR2 activates serum response factor (SRF)-downstream transcription of genes regulating actin cytoskeleton and migration. ROS levels, inside the tip cell, are also important to activate MST1 that phosphorylate FOXO1. Phosphorylated FOXO1 will enter the EC tip nuclei and promote transcription of polarity and migration-related genes. YAP/TAZ transcription factors are crucial for the activation of CDC42 and for adherens junction’s integrity and stabilization. WNT5A/ROR2 signaling pathway is important for the recruitment of vinculin (VCL) to adherens junctions to enhance intercellular force transmission, fundamental to coordinate collective cell polarity and migration. JBLs and JAILs are important for the migration of ECs and junctional stability. Both these structures use RAC1-mediated activation of ARP2/3 in order to promote actin polymerization and lamellipodia extension. These intricate signaling pathways are crucial for the establishment of EC polarity and migration and the collective cell behavior during sprouting angiogenesis.

VEGFA also activates expression of the transcription factor serum response factor (SRF) and its cofactors: myocardin-related transcription factors (MRTF)-A and -B – which are key regulators of the actin cytoskeleton (77). SRF/MRTFs promote the expression of genes involved in actin cytoskeleton dynamics and are critical for EC filopodia formation, tip cell contractility and EC migration (Fig. 1) (78, 79, 80, 81). Curiously, despite the general idea that filopodia are important for angiogenesis, Gerhardt and colleagues showed that inhibition of filopodia formation using low concentrations of latrunculin B, was compatible with the migration and guidance of endothelial tip cells in the intersegmental vessels of zebrafish (82). These observations suggested that ECs do not require filopodia for guidance and migration and thus questioned the real role and function of endothelial filopodia in angiogenesis, a matter still unresolved.

Focal adhesions are also crucial for EC migration. ECs can actively sense and perceive mechanical properties of the ECM, such as stiffness, composition and deformation. These ECM properties, through focal adhesions, lead to an activation of different signaling pathways that regulate migration and proliferation (83). For instance, integrin-linked kinase (ILK) and integrin β1 (ITGB1) have been associated with EC migration, controlling sprouting angiogenesis during retinal angiogenesis (84, 85). Focal adhesion kinase (FAK) seems to be crucial for EC migration since its depletion leads to an inhibition of tumor growth, reduced tumor angiogenesis and impairment of VEGF-induced neovascularization in adult mice (86). In addition, MAP4K4 was associated to promote efficient plasma membrane retraction during EC migration by regulating a signaling pathway linking moesin and ITGB1 (87). The Hippo pathway was also recently shown to be fundamental for EC migration and angiogenesis. The Hippo signaling transcription factors, YES-associated protein (YAP) and transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ), are key regulators of cell proliferation, differentiation and organogenesis (88, 89, 90). In sprouting angiogenesis, YAP and TAZ regulate EC proliferation and migration by directly modulating CDC42 activity and the actin cytoskeleton (Fig. 1) (91, 92, 93). In parallel, a YAP/TAZ-associated kinase – the mammalian sterile 20-like kinase 1 (MST1) – was shown to regulate tip cell behavior through a different transcription factor, FOXO1 (94). The authors showed that MST1 is activated by reactive oxygen species in response to hypoxia, leading to the phosphorylation of FOXO1 and its nuclear import. Nuclear FOXO1 will, in turn, activate the transcription of genes involved in the regulation of cell polarity and directional migration of tip cells toward hypoxic regions (Fig. 1) (94). Curiously, FOXO1 has been previously associated with the regulation of EC metabolism and quiescence (95). How FOXO1 can play such divergent roles remains to be understood, but metabolic control could be a key integrator in EC biology. Metabolism was previously found to regulate EC migration and to be substantially different between tip and stalk cells (96). Endothelial tip cells primarily use glycolysis for ATP production, and abrogation of a key glycolytic regulator phosphofructokinase-2/fructose-2, 6-biphosphatase isoform 3 (PFKFB3) impairs proliferation and migration of ECs (97, 98, 99). Remarkably, glycolytic enzymes are enriched at the leading edge and concentrate along F-actin in membrane ruffles, forming ‘ATP hot spots’, which are thought to generate high levels of ATP (97, 100). These ‘ATP hot spots’ sustain high energy-consuming actin dynamics generating filopodia and lamellipodia and thus tip cell invasion (96). Thus far, the molecular mechanisms described previously have been shown to regulate individual cell behavior; however, sprouting angiogenesis relies on collective cell migration. The mechanisms controlling angiogenic collective behavior are only now starting to be investigated. VE-cadherin plays a central role in the coordination of collective EC migration during sprouting angiogenesis (101, 102) and experiences tensile forces (force transmission between the migrating cells) (Fig. 1) (103). VE-cadherin force transmission was proposed to occur at specialized sub-cellular structures named as cadherin fingers (104). Also, coordination of EC movements were associated with oscillating lamellipodia-like protrusions emerging from EC junctions, so-called junction-associated intermittent lamellipodia (JAIL) and junction-based lamellipodia (JBL) (105, 106). JBLs and JAILs are structurally similar, yet JBLs seem to use cell–cell interaction via VE-cadherin to promote motility, while JAILs favor integrin-based adhesion (Fig. 1) (105, 106). Moreover, YAP/TAZ can integrate mechanical signals with BMP signaling to maintain junctional integrity while controlling EC rearrangements during sprouting angiogenesis (93). In this context, DLC1, a RHO GTPase activating protein, was shown to be a direct target of activated YAP/TAZ in the regulation of collective migration and sprouting angiogenesis (107). Non-canonical WNT signaling also regulates collective cell migration of ECs. WNT5A, a non-canonical WNT signaling ligand, activates CDC42 at cell junctions to reinforce coupling between adherens junctions and the actin cytoskeleton. This junctional coupling occurs by stabilization of vinculin binding to α-catenin, which allows efficient coordination of collective cell migration in sprouting angiogenesis (Fig. 1) (108).

Cell migration in vascular patterning

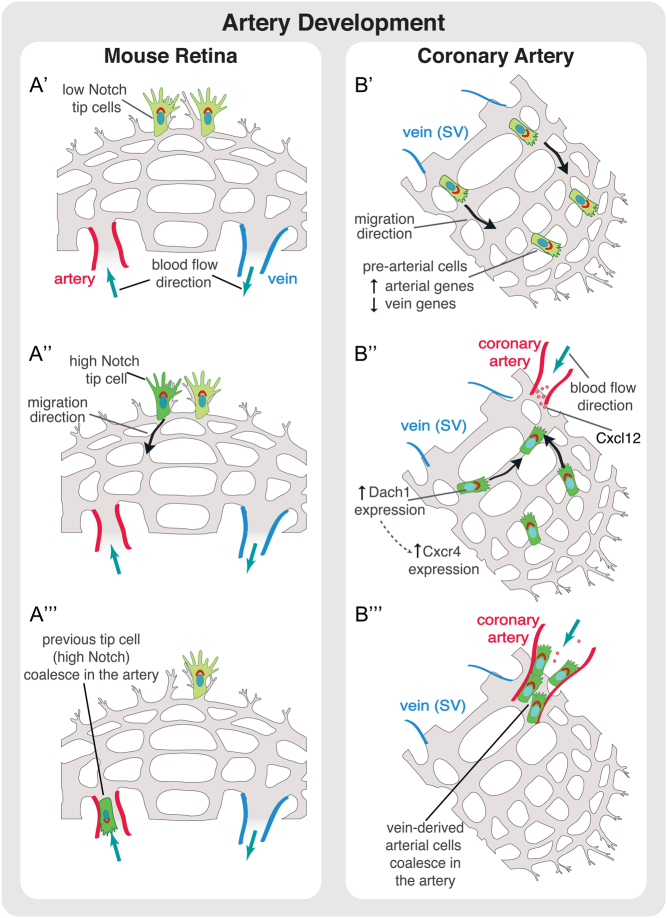

The endpoint of vascular patterning is the formation of a hierarchically organized vascular network according to tissue demands. A key aspect of vascular patterning is vessel regression, through which previously established vessel segments are removed. Some examples are the extensive vessel regression that occurs in the corpus luteum during luteolysis, the hyaloid vessels and pupillary vasculature in the eye, and the mammary gland during post-lactation involution (109). This type of vessel regression relies on EC apoptosis. Although the role of apoptosis in those cases is very well established, the contribution of apoptosis during vascular patterning is now considered to be minimal. To distinguish it from generalized vessel regression as in hyaloid vessels, we will use the term ‘vessel pruning’ for this type of vessel regression. Vessel pruning removes superfluous vessel connections generated by sprouting angiogenesis. Thus, vessel pruning decreases vascular complexity and increases vessel diameter, which is pivotal in the shaping of the arterial tree (110). Studies using mice and zebrafish showed that vessel pruning relies on EC migration rather than apoptosis (110, 111, 112, 113). In accordance, inhibition of EC apoptosis by deletion of the apoptosis effector proteins BAK and BAX did not alter the efficiency of vessel pruning or vascular patterning (114). The mechanisms regulating cell migration during vessel pruning remain elusive, although blood flow seems to be key. For instance, vessel pruning occurs in regions of no- or low flow (111, 112) and depends largely in the ability of ECs to polarize (front-rear polarity) against the flow direction (112, 115). In accordance, vascular pruning does not occur in mouse mutants where the coronary artery is not correctly connected to the aorta, its blood flow source (116, 117, 118). Additionally, modulation of blood flow using angiotensin II – a potent vasoconstrictor – interferes with vascular patterning and pruning (115, 119). The current concept suggests that, in response to blood flow, ECs migrate from low-flow/no-flow segments toward high-flow segments. This net movement of ECs toward high-flow branches leads to the regression of low-flow branches and stabilization of the high-flow branches (112) (Fig. 2). This concept implies the existence of flow-sensitive set-points determining both vessel pruning and vessel stability. In accordance with this notion, loss of the non-canonical WNT ligands WNT5A and WNT11 decreases the sensitivity of ECs to polarize against the blood flow direction promoting premature and excessive vessel pruning in mouse retina (115) (Fig. 2). VEGFR3 also modulates the EC sensitivity to fluid shear stress (120), but its role in vascular patterning has not been identified yet. In addition, Aplnr controls EC polarization against the flow direction, in zebrafish (121) (Fig. 2). Moreover, EC polarization against the flow was also shown to be affected in low-flow vessels upon PAR3 loss (122).

Figure 2.

Vascular patterning depends on blood flow and directional migration. (A) Schematic representation of a vessel network in a developing retina; flow direction and intensity in the plexus are indicated by blue arrows; EC polarity is indicated by the axis of polarity between the nucleus and Golgi complex. (B) Schematic representation of vessel pruning during vascular patterning. Increased levels of shear stress in vessels near the artery induce strong polarization (front-rear polarity) of ECs against the flow direction. The presence of asymmetries in shear stress between juxtaposed vessel segments leads to the migration of ECs away from low-/no-flow vessel segments toward high-flow vessels (black arrows). The directed migration of ECs toward high-flow segments leads to the stabilization of the newly formed vessels and pruning of low-flow vessel segments, detected by the presence of a basement membrane empty sleeve. (C) Molecules involved in flow-induced front-rear polarity. Proper polarization of ECs against flow direction is regulated by non-canonical WNT ligands, WNT5A and WNT11 and by the expression of APLNR (APJ) at EC membrane. Downregulation of these molecules leads to polarity and vascular remodeling defects.

Cellular contractility is also essential for vascular patterning. For instance, PI3K regulates actomyosin contractility to control EC rearrangement and vascular patterning in embryonic and postnatal angiogenesis (123, 124). Similarly, sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor-1 (S1P1/S1PR1), an activator of PI3K and RAC1 that stabilizes AJs, can be induced by laminar shear stress and promotes vascular homeostasis and stability of blood vessels in a flow-dependent way (125, 126). In zebrafish, the mechanosensitive transcription factor YAP translocates to the nucleus in response to blood flow and promotes the transcription of different genes involved in cell migration and proliferation. Deletion of YAP leads to vessel regression and excessive lumen stenosis (127). Additionally, primary cilia have been identified as flow sensors in ECs (128, 129, 130) and to regulate vascular patterning in a flow-dependent manner (131).

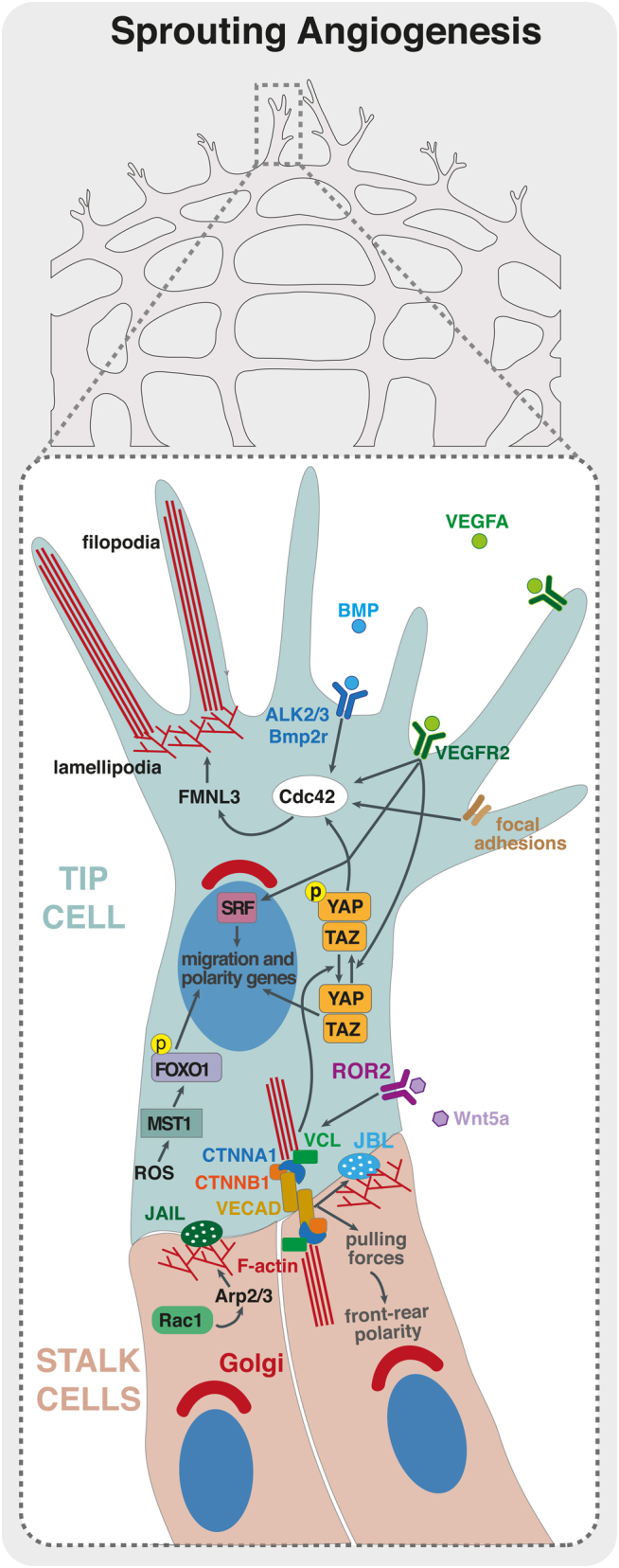

Remarkably, EC migration was also recently associated with artery formation, a process relying on migration against the flow direction. In zebrafish, vein-derived EC tip cells migrate to emerging arteries during zebrafish caudal regeneration, using CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling (132). Moreover, NOTCH-dependent activation of CXCR4 was also shown to be important for tip cell fusion with existing arteries (133). In the retinal vasculature, EC tip cells incorporate into developing arteries by migrating against the flow direction, coupling sprouting angiogenesis and artery formation. In the mouse retina, the mechanism seems to be dependent on NOTCH but independent of CXCR4 (61) (Fig. 3). A similar phenomenon appears to occur in coronary vessel development. Sprouting cells from venous origin give rise to pre-artery cells that aggregate and form coronary arteries – a process that requires blood flow (134) (Fig. 3). In heart, the transcription factor DACH1 regulates EC polarity and migration against flow direction during coronary artery remodeling through modulation of the chemokine CXCL12/SDF1. Deletion of Dach1 led to reduced caliber of coronary arteries without the correct hierarchical reduction in lumen size from proximal to distal regions (135).

Figure 3.

Cell migration during artery development. (A) Proposed model of artery development during angiogenesis in the mouse retina. (A’) Tip cells are activated at the sprouting front by VEGF signaling. (A‘‘) Some tip cells are activated by Notch signaling that promotes their migration away from the sprouting front in direction of the artery. (A‘‘‘) These previous tip cells coalesce in the artery leading to artery growth. (B) Proposed model for coronary artery development. (B’) Vein ECs derived from sinus venosus (SV) sprout by angiogenesis. (B‘‘ During this stage, and prior to the onset of blood flow, some SV-derived ECs start to increase the expression of arterial markers reducing the expression of venous ones. This genetic profile modification, accompanied to the onset of blood flow, induces migration of these pre-arterial cells. The migration of EC against flow direction is regulated by the transcription factor DACH1. DACH1 stimulates expression of CXCR4 in pre-arterial cells enabling these cells to respond to CXCL12, which is expressed by arterial cells. (B‘‘‘) ECs connect to the coronary artery leading to its growth and development.

Despite several evidences for the involvement of EC migration in vascular patterning, which we have highlighted in this review, a comprehensive understanding of the impact of EC polarity and EC migration for the different steps of vascular patterning is lacking. Moreover, we still miss a basic understanding of the mechanistic details of how ECs migrate within the vascular network during this process. In addition, other cellular processes, such as shape changes and cellular intercalation events, could contribute to vascular patterning without the requirement for effective cell migration (136, 137, 138). Finally, it is also important to underline that blood flow, vascular morphogenesis and EC polarity are tightly interlinked. Thus, genetic deletions affecting blood flow can feedback into EC polarity and migration, therefore, making it more difficult to distinguish between primary and secondary effects.

Endothelial cell migration in disease

The formation of a functional network of blood vessels is directly associated to the specific needs of each tissue, producing organotypic vasculatures (139). Disruption of this process causes severe pathologies, such as diabetic retinopathy, arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), cancer, atherosclerosis and cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs). In such a diverse spectrum of diseases, we subdivided the contribution of EC migration into two categories: (1) EC migration is influenced by extrinsic factors. EC migration in pathological conditions, such as in diabetic retinopathy, cancer and ischemic-related pathologies, plays a similar function as in developmental vessel formation. We propose that EC migratory behavior can only be compromised because of imbalances in pro- and anti-angiogenic molecules in the disease state. (2) EC migration is influenced by intrinsic factors. In this case, key genes regulating EC migration are defective and this leads to altered EC behavior that is causative of disease. In this section, we will present evidence on this second class of vascular pathologies.

Arteriovenous malformations

One clear example of the contribution of defective EC migration for disease is in AVM formation. AVMs arise due to the enlargement of direct connections between arteries and veins, bypassing an intervening capillary bed and leading to blood flow shunting (140). AVM formation is particularly sensitive to deficiencies in BMP signaling. Mutations or gene inactivation of BMP9 and BMP10, the BMP receptor activin receptor-like kinase 1 (ACVRL1/ALK1), its co-receptor endoglin (ENG) and the downstream signaling mediator cytosolic sterile alpha motif domain-containing 4A (Smad4), leads to the formation of AVMs (141, 142). In zebrafish, Corti et al. showed that Alk1 is important to sense hemodynamic forces and to control vessel caliber in nascent arteries (143). Further studies showed that loss of Alk1 imbalances EC migration against the blood flow direction. Alk1 deficiency leads to a reduction in EC numbers in the arterial segments close to the heart, causing a reduction in the caliber of proximal arteries and a concomitant dilation of distal vessels (144). These observations directly link cell migration and vessel caliber regulation under control of BMP/ALK1 signaling, and disruption of this pathway causes AVMs due to improper distribution of ECs in the vascular network (143, 144). Similar findings were observed in mouse. Eng-deficient ECs fail to polarize and migrate against blood flow direction. This results in the enlargement of arterioles that expand progressively to adjacent veins, forming the AV shunt, which suggests that these cells are not able to follow migratory cues from blood flow direction, pointing out an arteriole origin of ENG-related AVMs (145). Eng-deficiency was also associated with cell shape changes, suggesting that BMP signaling could also be important to determine the optimal vessel diameter via modulation of EC shape (140). How BMP instructs or regulates EC migration is still unclear. A study suggested that BMP signaling upregulates connexin 37 (CX37), a gap junction protein, which promotes migration in response to blood flow (146). Interestingly, BMP signaling is also influenced by blood flow, which sensitizes ECs to BMP9 by promoting ligand-independent interactions between ENG and ALK1 (147). Despite these data of the involvement of cell migration in AVM formation, further development and enlargement seems to be mediated by EC proliferation. Inhibition of pro-proliferative PI3K/AKT signaling in Eng- or Alk1-deficient mice significantly reduced the severity and frequency of AVMs (145, 148). Additionally, in Eng-deficient mice, VEGFR2 kinase inhibitor SU5416 reduced severity and frequency of AVMs by diminishing EC migration (145).

Vascular occlusion disease

Cell migration is also fundamental to reshape the vascular network upon artery occlusion. In these ischemic conditions, collateral arteries develop as a compensatory mechanism working as a functional bypass for blood flow. Two models explaining this mechanism exist: opening of pre-existent collateral vessels, which enlarge and functionalized to allow higher flow rates; and de novo formation of arteries upstream of the arterial occlusion. Using lineage-tracing methods, Bin Zhou group demonstrated that collaterals, upon arterial occlusion, developed exclusively by existing arterial ECs (149). However, how existing arterial ECs contributed to collateral opening and enlargement remained unclear. In this context, Kristy Red-Horse group found that EC migration is crucial in the formation of collateral vessels upon arterial occlusion in neonatal mouse (150), which was termed as ‘artery reassembly’. This model proposes that arterial ECs, downstream of the occlusion site, migrate away from obstructed arteries along existing capillaries to reassemble new collateral arteries. Remarkably, CXCR4-CXCL12 signaling is fundamental to guide the migration of arterial ECs (150). This mechanism seems to work only in the neonatal stage but can be reactivated by exogenous expression of CXCL12 in adult hearts (150).

Cerebral cavernous malformationsr

CCM is another vascular disease that occurs in the venous vasculature of the brain and the retina (151). The hereditary form is an autosomal dominant disease induced by the loss-of-function mutation in CCM1 (KRIT1), CCM2 (OSM) or CCM3 (PDCD10) (151). Inactivation of any of the CCM genes leads to the upregulation of Kruppel-like factor (KLF)2/4 transcription factors, downstream of enhanced extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 (ERK5) signaling pathway. Genetic inactivation of Klf2 or Klf4 rescues CCM formation in different mouse models (152, 153, 154). However, how this upregulation translates into the formation of CCM lesions remains poorly understood. Clonal expansion and impaired distribution of ECs that proliferate in venous regions have been proposed to drive CCM development. Clonal expansion and proliferation of Ccm1 and Ccm3 mutant cells have been linked to a process called endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT) (155). Through EndMT, similar to the original epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), ECs acquire mesenchymal-like phenotypic characteristics, such as an elongated morphology, increased motility and invasive capacity, which are a consequence of alterations in the actin cytoskeleton and in intercellular junctions (156). TGFβ signaling is a potent inducer of EndMT, promoting the expression of canonical EndMT transcription factors, such as SNAI1, SNAI2, and TWIST1 (157). Blockage of TGFβ or BMP prevents EndMT in vivo and decreases CCM lesion size (155). Interestingly, CCM1 and CCM2 proteins have also been suggested to control cell–cell junctions and cell–ECM adhesions by negatively regulating RhoA-dependent contractility activity (158), while CCM3 has been suggested to have a role in maintaining Golgi stability through the regulation of CDC42 signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans (159). In agreement with this observation, EC-specific deletion of CDC42 leads to CCM-like lesions in retina and brain (65, 154). This has led to the hypothesis that Cdc42 deficiency impairs the migration of ECs away from sites of enhanced proliferation, such as veins, and that impaired distribution of ECs within the vascular network would lead to a local accumulation of mutant cells that drives CCM development (65, 154). However, despite the established relationship among EndMT, EC contractility, and CDC42 with the process of cell migration in several other contexts, no direct link has yet been established between EC migration and CCM formation.

Conclusions

In this review, we described the relevance and the mechanisms involved in the regulation of EC migration during vascular morphogenesis and disease. Recent research has highlighted the extensive dynamics of ECs in all steps of vascular morphogenesis, which was previously only believed to occur during sprouting angiogenesis. Yet, we are only now starting to uncover the regulators and the mechanics of EC migration. A large number of mutants demonstrate defects in sprouting angiogenesis, with little effects on vascular patterning. The opposite is also true. Thus, despite the actin cytoskeleton being at the core of cell motility, these observations imply the existence of different modes of motility within the vasculature. Which biochemical and mechanical signals influence EC behavior and promote a switch in migration modes within the network? Which modes of migration do ECs use during sprouting or patterning? Moreover, how ECs sense and integrate diverse pro-motility cues remain unclear. In addition, ECs need to perform extensive cellular rearrangements without disrupting junction integrity and vessel barrier function. VE-cadherin dynamics are regulated by the actomyosin cytoskeleton and local turnover of junctional molecules needs to be tightly controlled, and eventually coupled, to exert protrusive behavior. JAILs and JBLs are promising discoveries; however, we still lack mechanistic details of the interface between the actin cytoskeleton and junctions in cell migration. Interestingly, VE-cadherin is key in the regulation of collective motility of ECs, and recent research demonstrated collective behaviors, highlighted by EC polarity patterns, both in sprouting angiogenesis and vascular patterning. Yet, artery and collateral formation indicate that ECs migrate as single cells. Can ECs switch between single and collective cell migration mode? What factors could control this switch in behavior?

Answering these questions could lead to fundamental leaps in our understanding of physiological angiogenesis. The emergent relevance of EC migration for the onset of vascular malformations further broadens the relevance of studying the basic mechanisms of EC motility.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of this review.

Funding

C A F was supported by European Research Council Starting Grant (AXIAL.EC; 679368), the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia funding (grants: IF/00412/2012; EXPL/BEX-BCM/2258/2013; PTDC/MED-PAT/31639/2017; PTDC/BIA-CEL/32180/2017), and a grant from the Fondation Leducq (17CVD03).

Author contribution statement

P B, C G F and C A F wrote, reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Francisca Vasconcelos and Yulia Carvalho for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Potente M, Mäkinen T. Vascular heterogeneity and specialization in development and disease. Nature Reviews: Molecular Cell Biology 2017. 18 477–494. ( 10.1038/nrm.2017.36) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaahtomeri K, Karaman S, Mäkinen T, Alitalo K. Lymphangiogenesis guidance by paracrine and pericellular factors. Genes and Development 2017. 31 1615–1634. ( 10.1101/gad.303776.117) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herbert SP, Stainier DYR. Molecular control of endothelial cell behaviour during blood vessel morphogenesis. Nature Reviews: Molecular Cell Biology 2011. 12 551–564. ( 10.1038/nrm3176) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcelo KL, Goldie LC, Hirschi KK. Regulation of endothelial cell differentiation and specification. Circulation Research 2013. 112 1272–1287. ( 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300506) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paffett-Lugassy N, Singh R, Nevis KR, Guner-Ataman B, O’Loughlin E, Jahangiri L, Harvey RP, Burns CG, Burns CE. Heart field origin of great vessel precursors relies on nkx2.5-mediated vasculogenesis. Nature Cell Biology 2013. 15 1362–1369. ( 10.1038/ncb2862) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Proulx K, Lu A, Sumanas S. Cranial vasculature in zebrafish forms by angioblast cluster-derived angiogenesis. Developmental Biology 2010. 348 34–46. ( 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.08.036) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mentzer SJ, Konerding MA. Intussusceptive angiogenesis: expansion and remodeling of microvascular networks. Angiogenesis 2014. 17 499–509. ( 10.1007/s10456-014-9428-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karthik S, Djukic T, Kim JD, Zuber B, Makanya A, Odriozola A, Hlushchuk R, Filipovic N, Jin SW, Djonov V. Synergistic interaction of sprouting and intussusceptive angiogenesis during zebrafish caudal vein plexus development. Scientific Reports 2018 8 1–15. ( 10.1038/s41598-018-27791-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in life, disease and medicine. Nature 2005. 438 932–936. ( 10.1038/nature04478) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ulvmar MH, Mäkinen T. Heterogeneity in the lymphatic vascular system and its origin. Cardiovascular Research 2016. 111 310–321. ( 10.1093/cvr/cvw175) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pollard TD. Actin and actin-binding proteins. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2016. 8 a018226 ( 10.1101/cshperspect.a018226) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goley ED, Welch MD. The Arp2/3 complex: an actin nucleator comes of age. Nature Reviews: Molecular Cell Biology 2006. 7 713–726. ( 10.1038/nrm2026) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rotty JD, Wu C, Bear JE. New insights into the regulation and cellular functions of the Arp2/3 complex. Nature Reviews: Molecular Cell Biology 2013. 14 7–12. ( 10.1038/nrm3492) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young LE, Heimsath EG, Higgs HN. Cell type-dependent mechanisms for formin-mediated assembly of filopodia. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2015. 26 4646–4659. ( 10.1091/mbc.E15-09-0626) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vicente-Manzanares M, Ma X, Adelstein RS, Horwitz AR. Non-muscle myosin II takes centre stage in cell adhesion and migration. Nature Reviews: Molecular Cell Biology 2009. 10 778–790. ( 10.1038/nrm2786) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huttenlocher A, Horwitz AR. Integrins in cell migration. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2011. 3 a005074 ( 10.1101/cshperspect.a005074) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elosegui-Artola A, Trepat X, Roca-Cusachs P. Control of mechanotransduction by molecular clutch dynamics. Trends in Cell Biology 2018. 28 356–367. ( 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.01.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parsons JT, Horwitz AR, Schwartz MA. Cell adhesion: integrating cytoskeletal dynamics and cellular tension. Nature Reviews: Molecular Cell Biology 2010. 11 633–643. ( 10.1038/nrm2957) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayor R, Etienne-Manneville S. The front and rear of collective cell migration. Nature Reviews: Molecular Cell Biology 2016. 17 97–109. ( 10.1038/nrm.2015.14) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamada KM, Sixt M. Mechanisms of 3D cell migration. Nature Reviews: Molecular Cell Biology 2019. 20 738–752. ( 10.1038/s41580-019-0172-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lamalice L, Le Boeuf F, Huot J. Endothelial cell migration during angiogenesis. Circulation Research 2007. 100 782–794. ( 10.1161/01.RES.0000259593.07661.1e) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter SB. Haptotaxis and the mechanism of cell motility. Nature 1967. 213 256–260. ( 10.1038/213256a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li S, Huang NF, Hsu S. Mechanotransduction in endothelial cell migration. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 2005. 96 1110–1126. ( 10.1002/jcb.20614) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iijima M, Huang YE, Devreotes P. Temporal and spatial regulation of chemotaxis. Developmental Cell 2002. 3 469–478. ( 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00292-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiner OD. Regulation of cell polarity during eukaryotic chemotaxis: the chemotactic compass. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 2002. 14 196–202. ( 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00310-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benard V, Bohl BP, Bokoch GM. Characterization of Rac and Cdc42 activation in chemoattractant-stimulated human neutrophils using a novel assay for active GTPases. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1999. 274 13198–13204. ( 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13198) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Etienne-Manneville S, Hall A. Cell polarity: Par6, aPKC and cytoskeletal crosstalk. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 2003. 15 67–72. ( 10.1016/S0955-0674(02)00005-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang C, Svitkina T. Filopodia initiation: focus on the Arp2/3 complex and formins. Cell Adhesion and Migration 2011. 5 402–408. ( 10.4161/cam.5.5.16971) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamazaki D, Suetsugu S, Miki H, Kataoka Y, Nishikawa SI, Fujiwara T, Yoshida N, Takenawa T. WAVE2 is required for directed cell migration and cardiovascular development. Nature 2003. 424 452–456. ( 10.1038/nature01770) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blanchoin L, Boujemaa-Paterski R, Sykes C, Plastino J. Actin dynamics, architecture, and mechanics in cell motility. Physiological Reviews 2014. 94 235–263. ( 10.1152/physrev.00018.2013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palazzo AF, Cook TA, Alberts AS, Gundersen GG. mDia mediates Rho-regulated formation and orientation of stable microtubules. Nature Cell Biology 2001. 3 723–729. ( 10.1038/35087035) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee JSH, Chang MI, Tseng Y, Wirtz D. Cdc42 mediates nucleus movement and MTOC polarization in Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts under mechanical shear stress. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2005. 16 871–880. ( 10.1091/mbc.e03-12-0910) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pandya P, Orgaz JL, Sanz-Moreno V. Modes of invasion during tumour dissemination. Molecular Oncology 2017. 11 5–27. ( 10.1002/1878-0261.12019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vitorino P, Meyer T. Modular control of endothelial sheet migration. Genes and Development 2008. 22 3268–3281. ( 10.1101/gad.1725808) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friedl P, Mayor R. Tuning collective cell migration by cell-cell junction regulation. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2017. 9 a029199 ( 10.1101/cshperspect.a029199) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lecuit T, Yap AS. E-cadherin junctions as active mechanical integrators in tissue dynamics. Nature Cell Biology 2015. 17 533–539. ( 10.1038/ncb3136) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Charras G, Yap AS. Tensile forces and mechanotransduction at cell–cell junctions. Current Biology 2018. 28 R445–R457. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2018.02.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Pascalis C, Etienne-Manneville S. Single and collective cell migration: the mechanics of adhesions. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2017. 28 1833–1846. ( 10.1091/mbc.E17-03-0134) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cleaver O, Krieg PA. VEGF mediates angioblast migration during development of the dorsal aorta in Xenopus. Development 1998. 125 3905–3914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lawson ND, Vogel AM, Weinstein BM. Sonic hedgehog and vascular endothelial growth factor act upstream of the notch pathway during arterial endothelial differentiation. Developmental Cell 2002. 3 127–136. ( 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00198-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shalaby F, Rossant J, Yamaguchi TP, Gertsenstein M, Wu XF, Breitman ML, Schuh AC. Failure of blood-island formation and vasculogenesis in Flk-1-deficient mice. Nature 1995. 376 62–66. ( 10.1038/376062a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferrara N, Carver-Moore K, Chen H, Dowd M, Lu L, O’Shea KS, Powell-Braxton L, Hillan KJ, Moore MW. Heterozygous embryonic lethality induced by targeted inactivation of the VEGF gene. Nature 1996. 380 439–442. ( 10.1038/380439a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carmeliet P, Ferreira V, Breier G, Pollefeyt S, Kieckens L, Gertsenstein M, Fahrig M, Vandenhoeck A, Harpal K, Eberhardt C, et al. Abnormal blood vessel development and lethality in embryos lacking a single VEGF allele. Nature 1996. 380 435–439. ( 10.1038/380435a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verma A, Bhattacharya R, Remadevi I, Li K, Pramanik K, Samant GV, Horswill M, Chun CZ, Zhao B, Wang E. et al. Endothelial cell-specific chemotaxis receptor (ecscr) promotes angioblast migration during vasculogenesis and enhances VEGF receptor sensitivity. Blood 2010. 115 4614–4622. ( 10.1182/blood-2009-10-248856) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Helker CSM, Schuermann A, Pollmann C, Chng SC, Kiefer F, Reversade B, Herzog W. The hormonal peptide Elabela guides angioblasts to the midline during vasculogenesis. eLife 2015. 4 e06726. ( 10.7554/eLife.06726) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roberts EM, Newson MJF, Pope GR, Landgraf R, Lolait SJ, O’Carroll AM. Abnormal fluid homeostasis in apelin receptor knockout mice. Journal of Endocrinology 2009. 202 453–462. ( 10.1677/JOE-09-0134) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kilari S, Cossette S, Pooya S, Bordas M, Huang YW, Ramchandran R, Wilkinson GA. Endothelial cell surface expressed chemotaxis and apoptosis regulator (ECSCR) regulates lipolysis in white adipocytes via the PTEN/AKT signaling pathway. PLoS One 2015. 10 e0144185 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0144185) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Semaphorin SW, Isogai S, Sato-Maeda M, Obinata M, Kuwada JY. Semaphorin3a1 regulates angioblast migration and vascular development in zebrafish embryos. Development 2003. 130 3227–3236. ( 10.1242/dev.00516) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McKenna CC, Ojeda AF, Spurlin J, Kwiatkowski S, Lwigale PY. Sema3A maintains corneal avascularity during development by inhibiting vegf induced angioblast migration. Developmental Biology 2014. 391 241–250. ( 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.04.017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hen G, Nicenboim J, Mayseless O, Asaf L, Shin M, Busolin G, Hofi R, Almog G, Tiso N, Lawson ND, et al. Venous-derived angioblasts generate organ-specific vessels during zebrafish embryonic development. Development 2015. 142 4266–4278. ( 10.1242/dev.129247) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adams RH, Alitalo K. Molecular regulation of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nature Reviews: Molecular Cell Biology 2007. 8 464–478. ( 10.1038/nrm2183) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hayashi H, Kume T. Foxc transcription factors directly regulate DII4 and hey2 expression by interacting with the VEGF-notch signaling pathways in endothelial cells. PLoS One 2008. 3 1–9. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0002401) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Corada M, Orsenigo F, Morini MF, Pitulescu ME, Bhat G, Nyqvist D, Breviario F, Conti V, Briot A, Iruela-Arispe ML, et al. Sox17 is indispensable for acquisition and maintenance of arterial identity. Nature Communications 2013. 4 2609 ( 10.1038/ncomms3609) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sacilotto N, Chouliaras KM, Nikitenko LL, Lu YW, Fritzsche M, Wallace MD, Nornes S, García-Moreno F, Payne S, Bridges E, et al. MEF2 transcription factors are key regulators of sprouting angiogenesis. Genes and Development 2016. 30 2297–2309. ( 10.1101/gad.290619.116) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hellström M, Phng LK, Hofmann JJ, Wallgard E, Coultas L, Lindblom P, Alva J, Nilsson AK, Karlsson L, Gaiano N, et al. Dll4 signalling through Notch1 regulates formation of tip cells during angiogenesis. Nature 2007. 445 776–780. ( 10.1038/nature05571) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Suchting S, Freitas C, le Noble F, Benedito R, Breant C, Duarte A, Eichmann A. The Notch ligand Delta-like 4 negatively regulates endothelial tip cell formation and vessel branching. PNAS 2007. 104 3225–3230. ( 10.1073/pnas.0611177104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Siekmann AF, Lawson ND. Notch signalling and the regulation of angiogenesis. Cell Adhesion and Migration 2007. 1 104–106. ( 10.4161/cam.1.2.4488) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jakobsson L, Franco CA, Bentley K, Collins RT, Ponsioen B, Aspalter IM, Rosewell I, Busse M, Thurston G, Medvinsky A, et al. Endothelial cells dynamically compete for the tip cell position during angiogenic sprouting. Nature Cell Biology 2010. 12 943–953. ( 10.1038/ncb2103) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bentley K, Franco CA, Philippides A, Blanco R, Dierkes M, Gebala V, Stanchi F, Jones M, Aspalter IM, Cagna G, et al. The role of differential VE-cadherin dynamics in cell rearrangement during angiogenesis. Nature Cell Biology 2014. 16 309–321. ( 10.1038/ncb2926) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Arima S, Nishiyama K, Ko T, Arima Y, Hakozaki Y, Sugihara K, Koseki H, Uchijima Y, Kurihara Y, Kurihara H. Angiogenic morphogenesis driven by dynamic and heterogeneous collective endothelial cell movement. Development 2011. 138 4763–4776. ( 10.1242/dev.068023) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pitulescu ME, Schmidt I, Giaimo BD, Antoine T, Berkenfeld F, Ferrante F, Park H, Ehling M, Biljes D, Rocha SF, et al. Dll4 and Notch signalling couples sprouting angiogenesis and artery formation. Nature Cell Biology 2017. 19 915–927. ( 10.1038/ncb3555) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hasan SS, Tsaryk R, Lange M, Wisniewski L, Moore JC, Lawson ND, Wojciechowska K, Schnittler H, Siekmann AF. Endothelial Notch signalling limits angiogenesis via control of artery formation. Nature Cell Biology 2017. 19 928–940. ( 10.1038/ncb3574) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Costa G, Harrington KI, Lovegrove HE, Page DJ, Chakravartula S, Bentley K, Herbert SP. Asymmetric division coordinates collective cell migration in angiogenesis. Nature Cell Biology 2016. 18 1292–1301. ( 10.1038/ncb3443) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dubrac A, Genet G, Ola R, Zhang F, Pibouin-Fragner L, Han J, Zhang J, Thomas JL, Chedotal A, Schwartz MA, et al. Targeting NCK-mediated endothelial cell front-rear polarity inhibits neovascularization. Circulation 2016. 133 409–421. ( 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017537) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Laviña B, Castro M, Niaudet C, Cruys B, Álvarez-Aznar A, Carmeliet P, Bentley K, Brakebusch C, Betsholtz C, Gaengel K. Defective endothelial cell migration in the absence of Cdc42 leads to capillary-venous malformations. Development 2018. 145 dev161182 ( 10.1242/dev.161182) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martin M, Veloso A, Wu J, Katrukha EA, Akhmanova A. Control of endothelial cell polarity and sprouting angiogenesis by non-centrosomal microtubules. eLife 2018. 7 e33864 ( 10.7554/eLife.33864) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fantin A, Lampropoulou A, Gestri G, Raimondi C, Senatore V, Zachary I, Ruhrberg C. NRP1 regulates CDC42 activation to promote filopodia formation in endothelial tip cells. Cell Reports 2015. 11 1577–1590. ( 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.05.018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hetheridge C, Scott AN, Swain RK, Copeland JW, Higgs HN, Bicknell R, Mellor H. The formin FMNL3 is a cytoskeletal regulator of angiogenesis. Journal of Cell Science 2012. 125 1420–1428. ( 10.1242/jcs.091066) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wakayama Y, Fukuhara S, Ando K, Matsuda M, Mochizuki N. Cdc42 mediates Bmp – induced sprouting angiogenesis through Fmnl3-driven assembly of endothelial filopodia in zebrafish. Developmental Cell 2015. 32 109–122. ( 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.11.024) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tan I, Yong J, Dong JM, Lim L, Leung T. A tripartite complex containing MRCK modulates lamellar actomyosin retrograde flow. Cell 2008. 135 123–136. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nohata N, Uchida Y, Stratman AN, Adams RH, Zheng Y, Weinstein BM, Mukouyama YS, Gutkind JS. Temporal-specific roles of Rac1 during vascular development and retinal angiogenesis. Developmental Biology 2016. 411 183–194. ( 10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.02.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zeng H, Zhao D, Mukhopadhyay D. KDR stimulates endothelial cell migration through heterotrimeric G protein Gq/11-mediated activation of a small GTPase RhoA. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002. 277 46791–46798. ( 10.1074/jbc.M206133200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zahra FT, Sajib MS, Ichiyama Y, Akwii RG, Tullar PE, Cobos C, Minchew SA, Doçi CL, Zheng Y, Kubota Y, et al. Endothelial RhoA GTPase is essential for in vitro endothelial functions but dispensable for physiological in vivo angiogenesis. Scientific Reports 2019 9 1–15. ( 10.1038/s41598-019-48053-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Adini I, Rabinovitz I, Sun JF, Prendergast GC, Benjamin LE. RhoB controls Akt trafficking and stage-specific survival of endothelial cells during vascular development. Genes and Development 2003. 17 2721–2732. ( 10.1101/gad.1134603) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Leszczynska K, Kaur S, Wilson E, Bicknell R, Heath VL. The role of RhoJ in endothelial cell biology and angiogenesis. Biochemical Society Transactions 2011. 39 1606–1611. ( 10.1042/BST20110702) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fukushima Y, Nishiyama K, Kataoka H, Fruttiger M, Fukuhara S, Nishida K, Mochizuki N, Kurihara H, Nishikawa SI, Uemura A. RhoJ integrates attractive and repulsive cues in directional migration of endothelial cells. EMBO Journal 2020. 39 e102930 ( 10.15252/embj.2019102930) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gau D, Roy P. SRF’ing and SAP’ing – the role of MRTF proteins in cell migration. Journal of Cell Science 2018. 131 jcs218222 ( 10.1242/jcs.218222) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chai J, Jones MK, Tarnawski AS. Serum response factor is a critical requirement for VEGF signaling in endothelial cells and VEGF‐induced angiogenesis. FASEB Journal 2004. 18 1264–1266. ( 10.1096/fj.03-1232fje) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Franco CA, Mericskay M, Parlakian A, Gary-Bobo G, Gao-Li J, Paulin D, Gustafsson E, Li Z. Serum response factor is required for sprouting angiogenesis and vascular integrity. Developmental Cell 2008. 15 448–461. ( 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.07.019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Franco CA, Blanc J, Parlakian A, Blanco R, Aspalter IM, Kazakova N, Diguet N, Mylonas E, Gao-Li J, Vaahtokari A, et al. SRF selectively controls tip cell invasive behavior in angiogenesis. Development 2013. 140 2321–2333. ( 10.1242/dev.091074) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Weinl C, Riehle H, Park D, Stritt C, Beck S, Huber G, Wolburg H, Olson EN, Seeliger MW, Adams RH, et al. Endothelial SRF/MRTF ablation causes vascular disease phenotypes in murine retinae. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2013. 123 2193–2206. ( 10.1172/JCI64201) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Phng L-K, Stanchi F, Gerhardt H. Filopodia are dispensable for endothelial tip cell guidance. Journal of Cell Science 2013. 126 e1–e1. ( 10.1242/dev.097352) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.DuFort CC, Paszek MJ, Weaver VM. Balancing forces: architectural control of mechanotransduction. Nature Reviews: Molecular Cell Biology 2011. 12 308–319. ( 10.1038/nrm3112) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Park H, Yamamoto H, Mohn L, Ambühl L, Kanai K, Schmidt I, Kim KP, Fraccaroli A, Feil S, Junge HJ, et al. Integrin-linked kinase controls retinal angiogenesis and is linked to Wnt signaling and exudative vitreoretinopathy. Nature Communications 2019. 10 5243 ( 10.1038/s41467-019-13220-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yamamoto H, Ehling M, Kato K, Kanai K, van Lessen M, Frye M, Zeuschner D, Nakayama M, Vestweber D, Adams RH. Integrin β1 controls VE-cadherin localization and blood vessel stability. Nature Communications 2015. 6 6429 ( 10.1038/ncomms7429) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tavora B, Batista S, Reynolds LE, Jadeja S, Robinson S, Kostourou V, Hart I, Fruttiger M, Parsons M, Hodivala-Dilke KM. Endothelial FAK is required for tumour angiogenesis. EMBO Molecular Medicine 2010. 2 516–528. ( 10.1002/emmm.201000106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vitorino P, Yeung S, Crow A, Bakke J, Smyczek T, West K, McNamara E, Eastham-Anderson J, Gould S, Harris SF, et al. MAP4K4 regulates integrin-FERM binding to control endothelial cell motility. Nature 2015. 519 425–430. ( 10.1038/nature14323) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Piccolo S, Dupont S, Cordenonsi M. The biology of YAP/TAZ: hippo signaling and beyond. Physiological Reviews 2014. 94 1287–1312. ( 10.1152/physrev.00005.2014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Boopathy GTK, Hong W. Role of hippo pathway-YAP/TAZ signaling in angiogenesis. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2019. 7 49 ( 10.3389/fcell.2019.00049) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zanconato F, Cordenonsi M, Piccolo S. YAP and TAZ: a signalling hub of the tumour microenvironment. Nature Reviews: Cancer 2019. 19 454–464. ( 10.1038/s41568-019-0168-y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sakabe M, Fan J, Odaka Y, Liu N, Hassan A, Duan X, Stump P, Byerly L, Donaldson M, Hao J, et al. YAP/TAZ-CDC42 signaling regulates vascular tip cell migration. PNAS 2017. 114 10918–10923. ( 10.1073/pnas.1704030114) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kim J, Kim YH, Kim J, Park DY, Bae H, Lee DH, Kim KH, Hong SP, Jang SP, Kubota Y, et al. YAP/TAZ regulates sprouting angiogenesis and vascular barrier maturation. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2017. 127 3441–3461. ( 10.1172/JCI93825) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Neto F, Klaus-Bergmann A, Ong YT, Alt S, Vion AC, Szymborska A, Carvalho JR, Hollfinger I, Bartels-Klein E, Franco CA, et al. YAP and TAZ regulate adherens junction dynamics and endothelial cell distribution during vascular development. eLife 2018. 7 e31037 ( 10.7554/eLife.31037) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kim YH, Choi J, Yang MJ, Hong SP, Lee CK, Kubota Y, Lim DS, Koh GY. A MST1–FOXO1 cascade establishes endothelial tip cell polarity and facilitates sprouting angiogenesis. Nature Communications 2019. 10 838 ( 10.1038/s41467-019-08773-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wilhelm K, Happel K, Eelen G, Schoors S, Oellerich MF, Lim R, Zimmermann B, Aspalter IM, Franco CA, Boettger T, et al. FOXO1 couples metabolic activity and growth state in the vascular endothelium. Nature 2016. 529 216–220. ( 10.1038/nature16498) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.De Bock K, Georgiadou M, Carmeliet P. Role of endothelial cell metabolism in vessel sprouting. Cell Metabolism 2013. 18 634–647. ( 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.08.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.De Bock K, Georgiadou M, Schoors S, Kuchnio A, Wong BW, Cantelmo AR, Quaegebeur A, Ghesquière B, Cauwenberghs S, Eelen G, et al. Role of PFKFB3-driven glycolysis in vessel sprouting. Cell 2013. 154 651–663. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.037) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Vandekeere S, Dewerchin M, Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis revisited: an overlooked role of endothelial cell metabolism in vessel sprouting. Microcirculation 2015. 22 509–517. ( 10.1111/micc.12229) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yetkin-Arik B, Vogels IMC, Nowak-Sliwinska P, Weiss A, Houtkooper RH, Van Noorden CJF, Klaassen I, Schlingemann RO. The role of glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration in the formation and functioning of endothelial tip cells during angiogenesis. Scientific Reports 2019. 9 12608 ( 10.1038/s41598-019-48676-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Culic O, Gruwel MLH, Schrader J. Energy turnover of vascular endothelial cells. American Journal of Physiology 1997. 273 C205–C213. ( 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.1.C205) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Taha AA, Taha M, Seebach J, Schnittler H-J. ARP2/3-mediated junction-associated lamellipodia control VE-cadherin-based cell junction dynamics and maintain monolayer integrity. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2013. 25 245–256. ( 10.1091/mbc.e13-07-0404) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sauteur L, Krudewig A, Herwig L, Ehrenfeuchter N, Lenard A, Affolter M, Belting HG. Cdh5/VE-cadherin promotes endothelial cell interface elongation via cortical actin polymerization during angiogenic sprouting. Cell Reports 2014. 9 504–513. ( 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.024) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lagendijk AK, Gomez GA, Baek S, Hesselson D, Hughes WE, Paterson S, Conway DE, Belting HG, Affolter M, Smith KA. et al. Live imaging molecular changes in junctional tension upon VE-cadherin in zebrafish. Nature Communications 2017. 8 1402 ( 10.1038/s41467-017-01325-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hayer A, Shao L, Chung M, Joubert LM, Yang HW, Tsai FC, Bisaria A, Betzig E, Meyer T. Engulfed cadherin fingers are polarized junctional structures between collectively migrating endothelial cells. Nature Cell Biology 2016. 18 1311–1323. ( 10.1038/ncb3438) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Paatero I, Sauteur L, Lee M, Lagendijk AK, Heutschi D, Wiesner C, Guzmán C, Bieli D, Hogan BM, Affolter M. et al. Junction-based lamellipodia drive endothelial cell rearrangements in vivo via a VE-cadherin-F-actin based oscillatory cell-cell interaction. Nature Communications 2018. 9 3545 ( 10.1038/s41467-018-05851-9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cao J, Ehling M, März S, Seebach J, Tarbashevich K, Sixta T, Pitulescu ME, Werner AC, Flach B, Montanez E. et al. Polarized actin and VE-cadherin dynamics regulate junctional remodelling and cell migration during sprouting angiogenesis. Nature Communications 2017. 8 2210 ( 10.1038/s41467-017-02373-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.van der Stoel M, Schimmel L, Nawaz K, van Stalborch AM, de Haan A, Klaus-Bergmann A, Valent ET, Koenis DS, van Nieuw Amerongen GP, de Vries CJ, et al. DLC1 is a direct target of activated YAP/TAZ that drives collective migration and sprouting angiogenesis. Journal of Cell Science 2020. 133 jcs239947 ( 10.1242/jcs.239947) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Carvalho JR, Fortunato IC, Fonseca CG, Pezzarossa A, Barbacena P, Dominguez-Cejudo MA, Vasconcelos FF, Santos NC, Carvalho FA, Franco CA. Non-canonical Wnt signaling regulates junctional mechanocoupling during angiogenic collective cell migration. eLife 2019. 8 e45853 ( 10.7554/eLife.45853) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Watson EC, Grant ZL, Coultas L. Endothelial cell apoptosis in angiogenesis and vessel regression. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2017. 74 4387–4403. ( 10.1007/s00018-017-2577-y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Udan RS, Vadakkan TJ, Dickinson ME. Dynamic responses of endothelial cells to changes in blood flow during vascular remodeling of the mouse yolk sac. Development 2013. 140 4041–4050. ( 10.1242/dev.096255) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chen Q, Jiang L, Li C,, Hu D, Bu J wen, Cai D, Du J. Haemodynamics-driven developmental pruning of brain vasculature in zebrafish. PLoS Biology 2012. 10 e1001374 ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001374) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Franco CA, Jones ML, Bernabeu MO, Geudens I, Mathivet T, Rosa A, Lopes FM, Lima AP, Ragab A, Collins RT. et al. Dynamic endothelial cell rearrangements drive developmental vessel regression. PLoS Biology 2015. 13 e1002125 ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002125) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lenard A, Daetwyler S, Betz C, Ellertsdottir E, Belting HG, Huisken J, Affolter M. Endothelial cell self-fusion during vascular pruning. PLoS Biology 2015. 13 e1002126 ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002126) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Watson EC, Koenig MN, Grant ZL, Whitehead L, Trounson E, Dewson G, Coultas L. Apoptosis regulates endothelial cell number and capillary vessel diameter but not vessel regression during retinal angiogenesis. Development 2016. 143 2973–2982. ( 10.1242/dev.137513) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Franco CA, Jones ML, Bernabeu MO, Vion AC, Barbacena P, Fan J, Mathivet T, Fonseca CG, Ragab A, Yamaguchi TP, et al. Non-canonical Wnt signalling modulates the endothelial shear stress flow sensor in vascular remodelling. eLife 2016. 5 e07727 ( 10.7554/eLife.07727) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chen HI, Poduri A, Numi H, Kivela R, Saharinen P, Mckay AS, Raftrey B, Churko J, Tian X, Zhou B, et al. VEGF-C and aortic cardiomyocytes guide coronary artery stem development. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2014. 124 4899–4914. ( 10.1172/JCI77483) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ivins S, Chappell J, Vernay B, Suntharalingham J, Martineau A, Mohun TJ, Scambler PJ. The CXCL12/CXCR4 axis plays a critical role in coronary artery development. Developmental Cell 2015. 33 455–468. ( 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.03.026) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Volz KS, Jacobs AH, Chen HI, Poduri A, McKay AS, Riordan DP, Kofler N, Kitajewski J, Weissman I, Red-Horse K. Pericytes are progenitors for coronary artery smooth muscle. eLife 2015. 4 1–22. ( 10.7554/eLife.10036) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lobov IB, Cheung E, Wudali R, Cao J, Halasz G, Wei Y, Economides A, Lin HC, Papadopoulos N, Yancopoulos GD, et al. The DII4/notch pathway controls postangiogenic blood vessel remodeling and regression by modulating vasoconstriction and blood flow. Blood 2011. 117 6728–6737. ( 10.1182/blood-2010-08-302067) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Baeyens N, Nicoli S, Coon BG, Ross TD, Van Den Dries K, Han J, Lauridsen HM, Mejean CO, Eichmann A, Thomas JL, et al. Vascular remodeling is governed by a vegfr3-dependent fluid shear stress set point. eLife 2015. 4 1–35. ( 10.7554/eLife.04645) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kwon HB, Wang S, Helker CSM, Rasouli SJ, Maischein HM, Offermanns S, Herzog W, Stainier DY. In vivo modulation of endothelial polarization by apelin receptor signalling. Nature Communications 2016. 7 11805 ( 10.1038/ncomms11805) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hikita T, Mirzapourshafiyi F, Barbacena P, Riddell M, Pasha A, Li M, Kawamura T, Brandes RP, Hirose T, Ohno S. et al. PAR‐3 controls endothelial planar polarity and vascular inflammation under laminar flow. EMBO Reports 2018. 19 e45253 ( 10.15252/embr.201745253) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Graupera M, Guillermet-Guibert J, Foukas LC, Phng LK, Cain RJ, Salpekar A, Pearce W, Meek S, Millan J, Cutillas PR, et al. Angiogenesis selectively requires the p110α isoform of PI3K to control endothelial cell migration. Nature 2008. 453 662–666. ( 10.1038/nature06892) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Angulo-Urarte A, Casado P, Castillo SD, Kobialka P, Kotini MP, Figueiredo AM, Castel P, Rajeeve V, Milà-Guasch M, Millan J, et al. Endothelial cell rearrangements during vascular patterning require PI3-kinase-mediated inhibition of actomyosin contractility. Nature Communications 2018. 9 4826 ( 10.1038/s41467-018-07172-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Jung B, Obinata H, Galvani S, Mendelson K, Ding BS SR, Skoura A, Kinzel B, Brinkmann V, Rafii S, Evans T. et al. Flow-regulated endothelial S1P receptor-1 signaling sustains vascular development. Developmental Cell 2012. 23 600–610. ( 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.07.015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Gaengel K, Niaudet C, Hagikura K, Siemsen BL, Muhl L, Hofmann JJ, Ebarasi L, Nyström S, Rymo S, Chen LL, et al. The sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor S1PR1 restricts sprouting angiogenesis by regulating the interplay between VE-cadherin and VEGFR2. Developmental Cell 2012. 23 587–599. ( 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.08.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Nakajima H, Yamamoto K, Agarwala S, Terai K, Fukui H, Fukuhara S, Ando K, Miyazaki T, Yokota Y, Schmelzer E. et al. Flow-dependent endothelial YAP regulation contributes to vessel maintenance. Developmental Cell 2017. 40 523.e6–536.e6. ( 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.02.019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Traub O, Berk BC. Brief review. Archives of Internal Medicine 1977. 137 1262 ( 10.1001/archinte.1977.03630210128042) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Goetz JG, Steed E, Ferreira RR, Roth S, Ramspacher C, Boselli F, Charvin G, Liebling M, Wyart C, Schwab Y. et al. Endothelial cilia mediate low flow sensing during zebrafish vascular development. Cell Reports 2014. 6 799–808. ( 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.01.032) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Baeyens N, Schwartz MA. Biomechanics of vascular mechanosensation and remodeling. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2016. 27 7–11. ( 10.1091/mbc.E14-11-1522) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Vion AC, Alt S, Klaus-Bergmann A, Szymborska A, Zheng T, Perovic T, Hammoutene A, Oliveira MB, Bartels-Klein E, Hollfinger I, et al. Primary cilia sensitize endothelial cells to BMP and prevent excessive vascular regression. Journal of Cell Biology 2018. 217 1651–1665. ( 10.1083/jcb.201706151) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Xu C, Hasan SS, Schmidt I, Rocha SF, Pitulescu ME, Bussmann J, Meyen D, Raz E, Adams RH, Siekmann AF. Arteries are formed by vein-derived endothelial tip cells. Nature Communications 2014. 5 5758 ( 10.1038/ncomms6758) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Hasan SS, Tsaryk R, Lange M, Wisniewski L, Moore JC, Lawson ND, Wojciechowska K, Schnittler H, Siekmann AF. Endothelial Notch signalling limits angiogenesis via control of artery formation. Nature Cell Biology 2017. 19 928–940. ( 10.1038/ncb3574) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Su T, Stanley G, Sinha R, D’Amato G, Das S, Rhee S, Chang AH, Poduri A, Raftrey B, Dinh TT, et al. Single-cell analysis of early progenitor cells that build coronary arteries. Nature 2018. 559 356–362. ( 10.1038/s41586-018-0288-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Chang AH, Raftrey BC, D’Amato G, Surya VN, Poduri A, Chen HI, Goldstone AB, Woo J, Fuller GG, Dunn AR. et al. DACH1 stimulates shear stress-guided endothelial cell migration and coronary artery growth through the CXCL12-CXCR4 signaling axis. Genes and Development 2017. 31 1308–1324. ( 10.1101/gad.301549.117) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Guirao B, Bellaïche Y. Biomechanics of cell rearrangements in Drosophila. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 2017. 48 113–124. ( 10.1016/j.ceb.2017.06.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Herrera-Perez RM, Kasza KE. Biophysical control of the cell rearrangements and cell shape changes that build epithelial tissues. Current Opinion in Genetics and Development 2018. 51 88–95. ( 10.1016/j.gde.2018.07.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Goodwin K, Nelson CM. Branching morphogenesis. Development 2020. 147 dev184499 ( 10.1242/dev.184499) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Augustin HG, Koh GY. Organotypic vasculature: from descriptive heterogeneity to functional pathophysiology. Science 2017. 357 1–22. ( 10.1126/science.aal2379) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Sugden WW, Meissner R, Aegerter-Wilmsen T, Tsaryk R, Leonard EV, Bussmann J, Hamm MJ, Herzog W, Jin Y, Jakobsson L, et al. Endoglin controls blood vessel diameter through endothelial cell shape changes in response to haemodynamic cues. Nature Cell Biology 2017. 19 653–665. ( 10.1038/ncb3528) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Peacock HM, Caolo V, Jones EAV. Arteriovenous malformations in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: looking beyond ALK1-NOTCH interactions. Cardiovascular Research 2016. 109 196–203. ( 10.1093/cvr/cvv264) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Cunha SI, Magnusson PU, Dejana E, Lampugnani MG. Deregulated TGF-β/BMP signaling in vascular malformations. Circulation Research 2017. 121 981–999. ( 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.309930) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]