Abstract

Protein arginine methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5) belongs to a family of enzymes that regulate the posttranslational modification of histones and other proteins via methylation of arginine. Methylation of histones is linked to an increase in transcription and regulates a manifold of functions such as signal transduction and transcriptional regulation. PRMT5 has been shown to be upregulated in the tumor environment of several cancer types, and the inhibition of PRMT5 activity was identified as a potential way to reduce tumor growth. Previously, four different modes of PRMT5 inhibition were known—competing (covalently or non-covalently) with the essential cofactor S-adenosyl methionine (SAM), blocking the substrate binding pocket, or blocking both simultaneously. Herein we describe an unprecedented conformation of PRMT5 in which the formation of an allosteric binding pocket abrogates the enzyme’s canonical binding site and present the discovery of potent small molecule allosteric PRMT5 inhibitors.

Keywords: PRMT5, allosteric inhibition, methyltransferase, peptide competitive, SAM competitive, crystal structure

Members of the protein arginine methyl transferase (PRMT) family mono- or dimethylate arginine residues by catalyzing the transfer of a methyl group from the cofactor S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) to a guanidine nitrogen atom. They are categorized into three different classes1 with PRMT5 and PRMT9 belonging to the class II PRMTs that are able to symmetrically dimethylate arginine residues.2 PRMT enzymes regulate a variety of cellular processes including gene expression via histone methylation, signal transduction, mRNA splicing, and DNA repair.3−7

Methylosome protein 50 (MEP50) has been identified as a crucial binding partner for PRMT5, increasing its enzymatic activity.8,9 The PRMT5–MEP50 complex specifically methylates arginine residues on histones H2A, H3, and H45,10 as well as transcription factors and other proteins.7,11 PRMT5 is overexpressed in certain cancer types including lung, colorectal, and liquid tumors,4 and the inhibition of PRMT5 has been linked to tumor regression in mouse models.12,13

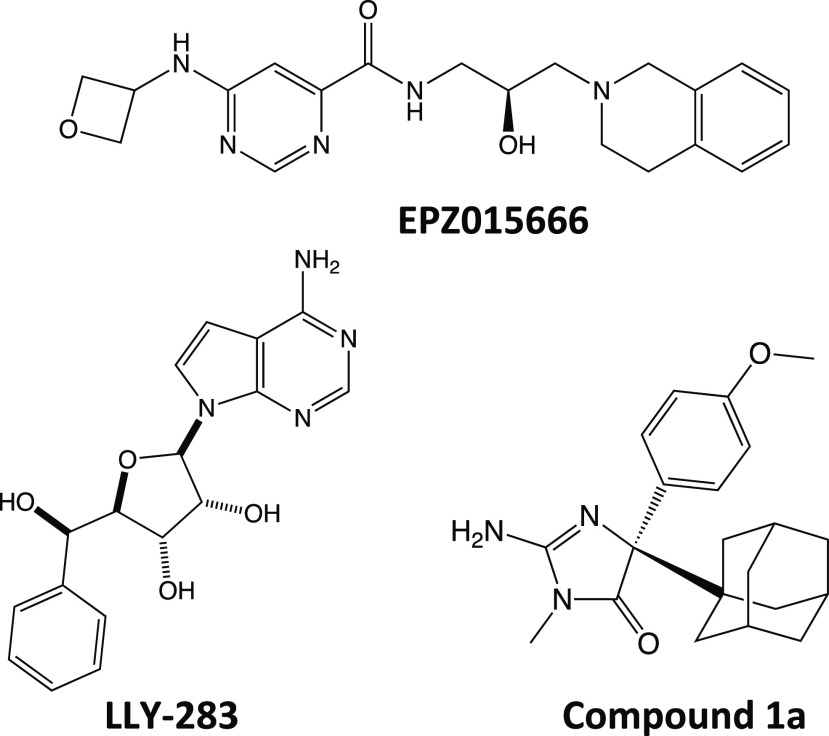

Different modes of PRMT5 inhibition have been reported in the literature, with small molecule inhibitors competing with either the protein substrate or the SAM cofactor. A natural inhibitor of PRMT5 is methylthioadenosine (MTA) which is converted to adenosine and 5-methylthioribose-1-phosphate by the enzyme methylthioadenosine phosphorylase (MTAP).14 In cancer cells, MTAP has been found as one of the more commonly deleted genes resulting in an increased concentration of MTA and partial inhibition of PRMT5 in a SAM-competitive manner.15 Examples for designed small molecule inhibitors include the peptide-competitive inhibitor EPZ015666,16 which binds in the catalytic substrate binding site in a SAM-uncompetitive fashion, and LLY-283,17 a SAM-competitive inhibitor that binds in the SAM binding site (Figure 1). A dual SAM/substrate PRMT5 inhibitor has been described (JNJ-64619178)18 that competes with both the protein substrate as well as SAM by binding in the SAM binding site and extending into the catalytic site of PRMT5, thus prohibiting the binding of the substrate. Additionally, covalent inhibitors have been developed and form a covalent bond with Cys449 in the SAM binding site.19 Here, we describe the binding of an allosteric inhibitor which stabilizes an alternative state of the enzyme in which large portions of the catalytic site are displaced precluding both substrate and SAM from binding.

Figure 1.

Structures of EPZ015666, LLY-283, and 1a.

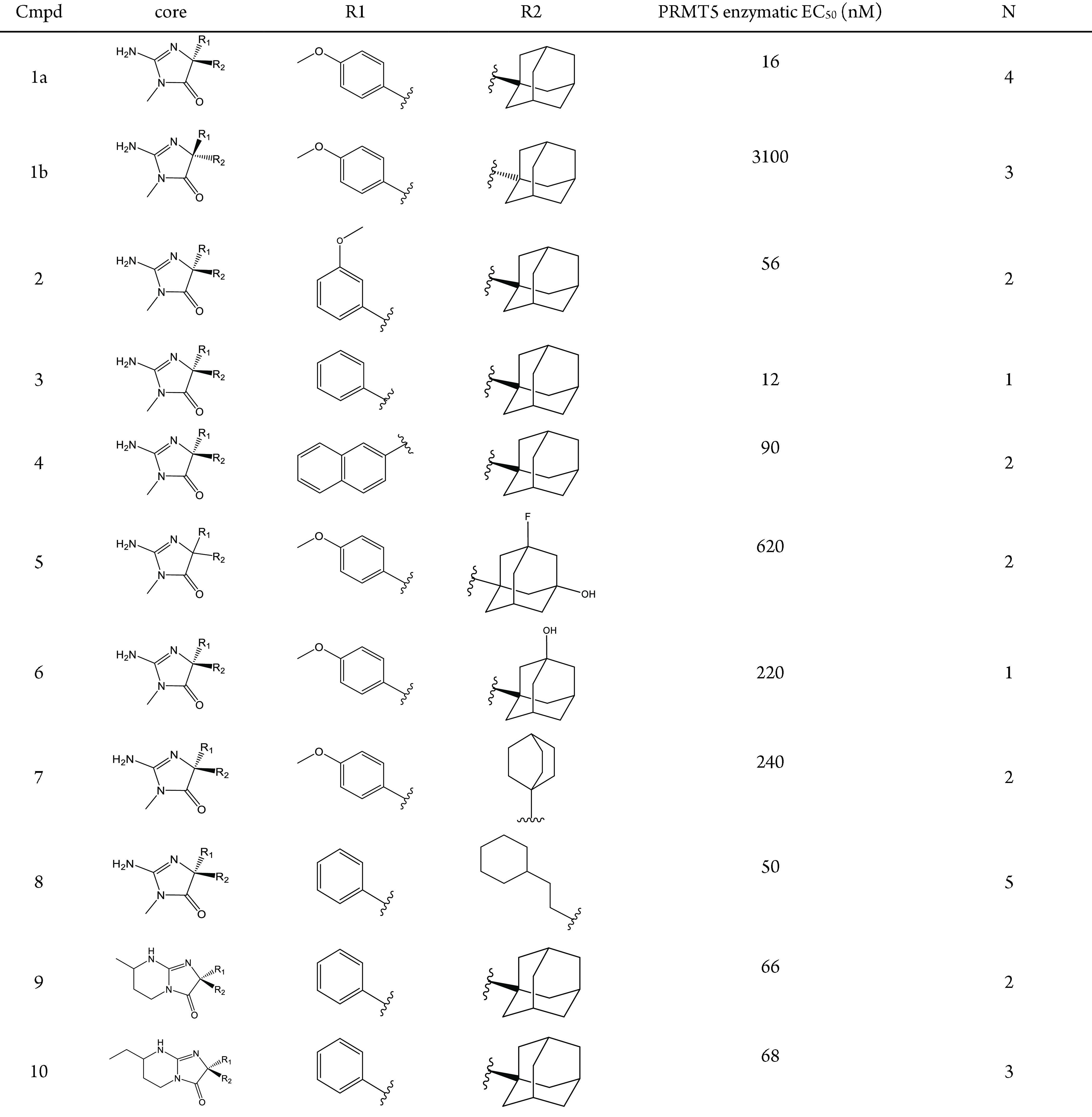

Compound 1a (Figure 1) was previously described as a BACE1 and BACE2 inhibitor20 and was also identified as a potent PRMT5 inhibitor through a high throughput screening campaign. 1a showed on-target potency with an EC50 of 16 nM in a biochemical methylation assay (Table 1; raw data curves in Figure S1). Cell-based inhibition of 4.6 μM EC50 was measured in MCF7 cells via quantitation of symmetrically dimethylated nuclear protein levels using high content imaging technology (methods in Supporting Information; high-content cellular images shown in Figure S2). This compound exhibited slow binding kinetics with an approximate on-rate of ka = ∼1000 M–1 s–1 (Figure S3) which is nearly 4 orders of magnitude slower than a typical fast binding step (instrumental upper limit is 5 × 107 M–1 s–1).21 While the (S)-enantiomer 1b was described as the more potent inhibitor of BACE1 and BACE2, the (R)-enantiomer (1a) is nearly 200-fold more potent than the (S)-enantiomer for PRMT5 in the biochemical assay. 1a and related analogs were prepared as described in the Supporting Information.

Table 1. Allosteric Inhibitor Biochemical Data.

To understand the binding mode of this novel PRMT5 inhibitor PRMT5:MEP50 was cocrystallized with 1a. The structure was solved at 2.7 Å resolution with one PRMT5:MEP50 complex in the asymmetric unit, unambiguous ligand density, and an overall Rmerge of 0.07 (Table S1). Additional details of crystallization protocols and structural statistics can be found in the Supporting Information. Atomic coordinates and structure factor files have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (6UXX).

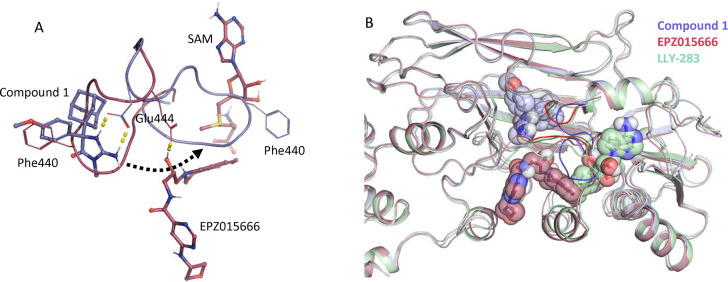

The cocrystal structure of the PRMT5:MEP50 complex with 1a reveals a unique binding mode and significant structural changes in the protein backbone (Figure 2A). An 11 amino acid loop consisting of residues Glu435 through Leu445 is displaced by up to 16.5 Å opening a new binding pocket. This movement causes the residues of the loop to both occupy the SAM binding site and occlude the substrate binding site so that neither SAM nor peptide substrate would be expected to bind. This conformational change was unexpected as published structures of PRMT enzymes both with and without orthosteric inhibitors bound reveal the relative stability of this loop. Despite sharing low sequence homology the backbone atoms of this amino acid loop for PRMT1-PRMT8 are positioned within 1.29 ± 0.57 Å RMSD (Figure S4, Figure S5, and Table S2). We hypothesize that the slow on rate for this compound is due to the required large loop movement needed for formation of the allosteric pocket.

Figure 2.

(A) Superposition of PRMT5:MEP50 cocrystal structures highlights the significant 11 amino acid loop movement. The currently reported structure with 1a is shown in slate blue overlaid with the EPZ015666-bound structure in maroon. (B) An overlay of the 1a-bound structure (slate blue), EPZ015666-bound structure (maroon), and LLY-283-bound structure (green) shows the localized nature of the 11-residue loop movement (shown in brighter colors) as the rest of the PRMT5 protein fold remains unaffected.

Figure 2B shows the binding mode of this novel allosteric inhibitor in the context of the other known modes of inhibition, specifically substrate-competitive and SAM-competitive inhibitors. While significant, the loop movement is highly localized and no other large-scale changes in protein conformation are seen between the three structures.

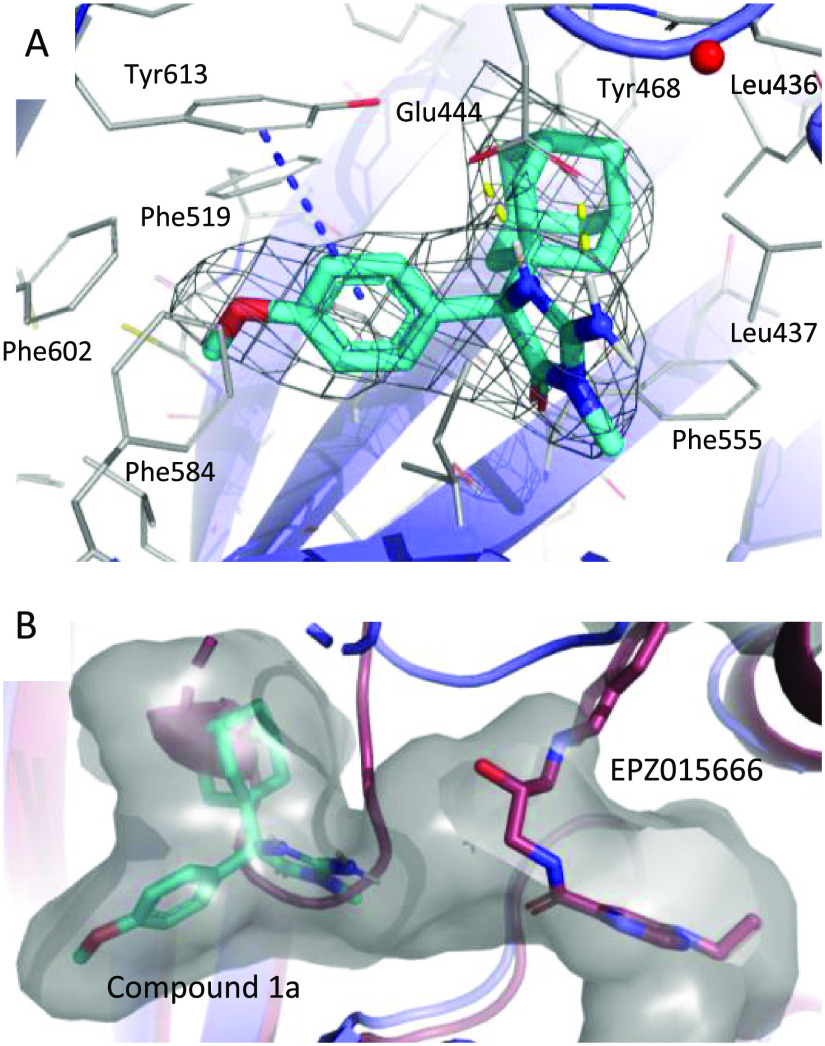

1a was observed to form several key interactions with nearby protein residues in the allosteric site (Figure 3). The adamantane moiety of 1a binds in a mostly hydrophobic pocket and is surrounded by two leucine residues (Leu436 and Leu437), two phenylalanines (Phe519 and Phe555), and a tyrosine residue (Tyr468). The methoxyphenyl group of 1a is buried between several aromatic residues (Phe519, Phe584, Phe602) and is engaged in an edge to face stacking interaction with Tyr613. Interestingly, the methoxyphenyl substituent replaces a phenylalanine (Phe440) of PRMT5 present in the EPZ015666-bound crystal structure (Figure 2A) while the center of mass of Phe440 is displaced roughly 22 Å to occupy the canonical SAM binding site. The amine of the iminohydantoin core is interacting via a hydrogen bond with Glu444, one of the key catalytic residues involved in the methylation of substrates (Figure 3A). Compared to the EPZ015666-bound crystal structure, the Cα of Glu444 is only shifted about 2 Å; however, the overall loop movement and rotation of Glu444 relocates the side chain carboxyl by approximately 4.5 Å to form the interaction with 1a.

Figure 3.

(A) Closeup view of 1a in the allosteric binding pocket of PRMT5. 1a shown as cyan sticks in the 2fo-fc electron density contoured to 1σ. (B) Superposition of 1a and EPZ015666-bound structures shown in cyan/slate blue and maroon, respectively. The solvent-accessible channel is shown in gray, highlighting the open channel between 1a and the canonical substrate binding pocket.

Visual inspection of the binding site revealed additional space between the adamantyl group and several of the surrounding residues enabling future inhibitor design (Figure 3). To further test the flexibility of the allosteric pocket, analogs with substituents at both positions off the iminohydantoin core were prepared (Table 1). Moving the methoxy group from the para to the meta position of the benzene ring at R1 is tolerated, though a small loss in biochemical potency is observed (2). Furthermore, the methoxyphenyl ring could be replaced by a naphthalene (4) and retain potency as well as the binding position within the allosteric pocket (data not shown). Simplifying the R1 substituent to an unsubstituted phenyl resulted in 3, which retained its biochemical potency.

Introducing additional polar groups on the adamantyl moiety was not well tolerated; for example, addition of an alcohol group to the adamantyl moiety resulted in a loss of potency (Table 1, Compounds 5 and 6). Replacing the adamantane with other hydrophobic groups was tolerated but resulted in a loss of potency. Substituting a bicyclo[2.2.2]octane (7) resulted in a 16-fold loss of potency in the biochemical assay compared to 1a. Similar observations were made when replacing the adamantane with a propylcyclohexane. In the context of the des-methoxy R1 substituent, 8 lost 5-fold potency in the biochemical assay.

The crystal structure of 1a also revealed the opening of a small channel from the allosteric binding site toward the canonical substrate binding site, offering the opportunity to grow the molecule in this direction (Figure 3B). Cyclization of the core allowed the introduction of small substitutions along a trajectory predicted to access this channel, resulting in 9 and 10. Both 9 and 10 lost about 5- to 6-fold biochemical potency compared to parent 3.

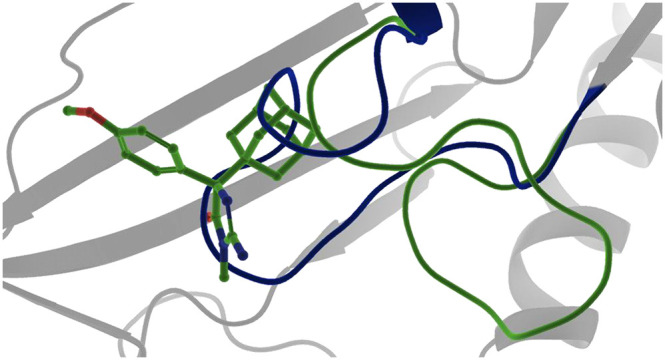

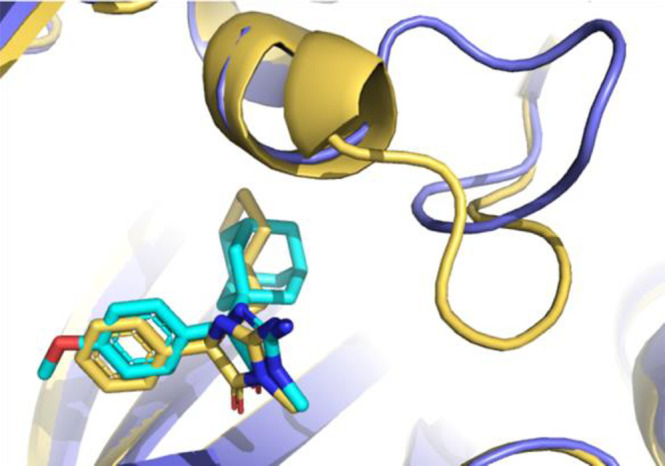

Interestingly, structural insight into the binding mode of 8 revealed that alternative configurations of the 11 amino acid long loop can be stabilized by the allosteric inhibitors (Figure 4; PDB ID 6UXY). 8 binds to an intermediate state of the loop which resides between the substrate-bound conformation and the conformation that is stabilized by 1a. This indicates that although this loop appears conformationally inflexible in the presence of orthosteric inhibitors a configurational landscape might exist in which different loop conformations can be stabilized depending on the allosteric inhibitor present. In both cases for which we have structural data, the loop prohibits the binding of SAM. However, alternative configurations in which both an allosterically binding molecule and SAM are bound seem possible.

Figure 4.

Overlay of the structures bound to 1a (cyan/slate blue) and 8 (yellow) revealing a configurational landscape of stable loop conformations.

In summary, we report to our knowledge the first allosteric dual substrate- and SAM-competitive inhibitor of PRMT5. Compared to EPZ015666 and LLY-283, these allosteric inhibitors bind to a PRMT5 conformation in which an 11 amino acid loop is displaced by several Ångströms, blocking the SAM binding site and abrogating the substrate binding site. We believe that this rearrangement is both energetically unfavorable and conformationally rare and may be the contributing factor to the observed slow on-rate. Additional design of analogs showed tractable SAR and revealed that additional loop conformations exist to which small molecules can bind. We report here two crystal structures with resolutions 2.7 Å or better that shed light on the molecular interactions of the allosteric inhibitors with the receptor. Previously, selective small molecule allosteric inhibitors for PRMT3 were identified22 to occupy a pocket aside of the substrate or SAM binding sites (see Figure S6) and were shown to be noncompetitive.23 In contrast to 1a, the known PRMT3 inhibitors do not induce large scale changes of the protein backbone24 (see Figure S7). Recently, an allosteric inhibitor of PRMT6 was developed by the Structural Genomics Consortium (SGC).25 Our results add PRMT5 to the list of known allosterically inhibitable PRMTs and combined with substrate-competitive (EPZ015666), SAM-competitive (LLY-283), dual SAM/substrate inhibitors (JNJ-64619178), and covalent SAM-competitive inhibitors (Prelude Therapeutics), this marks the fifth reported mode of inhibition for PRMT5.

Acknowledgments

We thank Charles Lesburg for helpful comments on the manuscript. We thank Donovon Adpressa and Xiao Wang for their work to determine the absolute stereochemistry of compounds 1a and 1b. We thank Viva Biotech for help with crystallography and data collection. We thank Lianyun Zhao and the WuXi AppTech chemistry team for help with the compound syntheses discussed in this article. We would also like to thank the reviewers for their thoughtful comments and efforts toward improving our manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- PRMT5

protein arginine methyl transferase

- SAM

S-adenosylmethionine

- MEP50

methylosome protein 50

- MTA

methylthioadenosine

- MTAP

methylthioadenosine phosphorylase

- BACE

beta-sacretase

- RMSD

root-mean-square deviation

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00525.

Experimental procedures for the biochemical assay, cell-based assay, SPR studies, chemical syntheses, NMR and ECD studies for the determination of absolute stereochemistry, protein expression and purifications, and X-ray crystallography. Also included is the crystallography data collection and refinement statistics, PRMT loop comparisons, and SPR raw data. (PDF)

Accession Codes

Compound 1a, 6UXX; compound 8, 6UXY.

Author Contributions

Rachel L. Palte and Sebastian E. Schneider contributed equally to the manuscript.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): All authors are or were employees of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

Supplementary Material

References

- Bedford M. T.; Clarke S. G. Protein arginine methylation in mammals: who, what, and why. Mol. Cell 2009, 33, 1–13. 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe T. L.; Frankel A.; Lee J. H.; Cook J. R.; Yang Z. H.; Pestka S.; Clarke S. PRMT5 (Janus kinase-binding protein 1) catalyzes the formation of symmetric dimethylarginine residues in proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 32971–32976. 10.1074/jbc.M105412200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson M.; Durant S. T.; Cho E. C.; Sheahan S.; Edelmann M.; Kessler B.; La Thangue N. B. Arginine methylation regulates the p53 response. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008, 10, 1431. 10.1038/ncb1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.; Bedford M. T. Protein arginine methyltransferases and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 37–50. 10.1038/nrc3409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q.; Rank G.; Tan Y. T.; Li H.; Moritz R. L.; Simpson R. J.; Cerruti L.; Curtis D. J.; Patel D. J.; Allis C. D.; Cunningham J. M. PRMT5-mediated methylation of histone H4R3 recruits DNMT3A, coupling histone and DNA methylation in gene silencing. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009, 16, 304–311. 10.1038/nsmb.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auclair Y.; Richard S. The role of arginine methylation in the DNA damage response. DNA Repair 2013, 12, 459–465. 10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karkhanis V.; Hu Y. J.; Baiocchi R. A.; Imbalzano A. N.; Sif S. Versatility of PRMT5-induced methylation in growth control and development. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2011, 36, 633–641. 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho M. C.; Wilczek C.; Bonanno J. B.; Xing L.; Seznec J.; Matsui T.; Carter L. G.; Onikubo T.; Kumar P. R.; Chan M. K.; Brenowitz M. Structure of the arginine methyltransferase PRMT5-MEP50 reveals a mechanism for substrate specificity. PLoS One 2013, 8, e57008 10.1371/journal.pone.0057008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonysamy S.; Bonday Z.; Campbell R. M.; Doyle B.; Druzina Z.; Gheyi T.; Han B.; Jungheim L. N.; Qian Y.; Rauch C.; Russell M. Crystal structure of the human PRMT5: MEP50 complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012, 109, 17960–17965. 10.1073/pnas.1209814109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ancelin K.; Lange U. C.; Hajkova P.; Schneider R.; Bannister A. J.; Kouzarides T.; Surani M. A. Blimp1 associates with Prmt5 and directs histone arginine methylation in mouse germ cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006, 8, 623–630. 10.1038/ncb1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tee W. W.; Pardo M.; Theunissen T. W.; Yu L.; Choudhary J. S.; Hajkova P.; Surani M. A. Prmt5 is essential for early mouse development and acts in the cytoplasm to maintain ES cell pluripotency. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 2772–2777. 10.1101/gad.606110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik S.; Liu F.; Veazey K. J.; Gao G.; Das P.; Neves L. F.; Lin K.; Zhong Y.; Lu Y.; Giuliani V.; Bedford M. T. Genetic deletion or small-molecule inhibition of the arginine methyltransferase PRMT5 exhibit anti-tumoral activity in mouse models of MLL-rearranged AML. Leukemia 2018, 32, 499–509. 10.1038/leu.2017.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan-Penebre E.; Kuplast K. G.; Majer C. R.; Boriack-Sjodin P. A.; Wigle T. J.; Johnston L. D.; Rioux N.; Munchhof M. J.; Jin L.; Jacques S. L.; West K. A. A selective inhibitor of PRMT5 with in vivo and in vitro potency in MCL models. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015, 11, 432–437. 10.1038/nchembio.1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kryukov G. V.; Wilson F. H.; Ruth J. R.; Paulk J.; Tsherniak A.; Marlow S. E.; Vazquez F.; Weir B. A.; Fitzgerald M. E.; Tanaka M.; Bielski C. M. MTAP deletion confers enhanced dependency on the PRMT5 arginine methyltransferase in cancer cells. Science 2016, 351, 1214–1218. 10.1126/science.aad5214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavrakis K. J.; McDonald E. R.; Schlabach M. R.; Billy E.; Hoffman G. R.; deWeck A.; Ruddy D. A.; Venkatesan K.; Yu J.; McAllister G.; Stump M. Disordered methionine metabolism in MTAP/CDKN2A-deleted cancers leads to dependence on PRMT5. Science 2016, 351, 1208–1213. 10.1126/science.aad5944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan K. W.; Rioux N.; Boriack-Sjodin P. A.; Munchhof M. J.; Reiter L. A.; Majer C. R.; Jin L.; Johnston L. D.; Chan-Penebre E.; Kuplast K. G.; Porter Scott M. Structure and property guided design in the identification of PRMT5 tool compound EPZ015666. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 162–166. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonday Z. Q.; Cortez G. S.; Grogan M. J.; Antonysamy S.; Weichert K.; Bocchinfuso W. P.; Li F.; Kennedy S.; Li B.; Mader M. M.; Arrowsmith C. H. LLY-283, a potent and selective inhibitor of arginine methyltransferase 5, PRMT5, with antitumor activity. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 612–617. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T.; Brehmer D.; Beke L.; Boeckx A.; Diels G. S.; Gilissen R. A.; Lawson E. C.; Pande V.; Parade M. C.; Schepens W. B.; Thuring J. W.; inventors Novel 6–6 bicyclic aromatic ring substituted nucleoside analogues for use as prmt5 inhibitors. United States patent application US 2018, 15/755, 475. [Google Scholar]

- Lin H.; Wang M.; Zhang Y. W.; Tong S.; Leal R. A.; Shetty R.; Vaddi K.; Luengo J. I. Discovery of potent and selective covalent protein arginine methyl-transferase 5 (PRMT5) inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 1033–1038. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamas M. S.; Erdei J.; Gunawan I.; Turner J.; Hu Y.; Wagner E.; Fan K.; Chopra R.; Olland A.; Bard J.; Jacobsen S. Design and synthesis of 5, 5′-disubstituted aminohydantoins as potent and selective human β-secretase (BACE1) inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 1146–1158. 10.1021/jm901414e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GE Healthcare Life Sciences. Biacore T200. Available at https://www.gelifesciences.com/en/us/shop/protein-analysis/spr-label-free-analysis/systems/biacore-t200-p-05644 (accessed 2019-10-30).

- Liu F.; Li F.; Ma A.; Dobrovetsky E.; Dong A.; Gao C.; Korboukh I.; Liu J.; Smil D.; Brown P. J.; Frye S. V. Exploiting an allosteric binding site of PRMT3 yields potent and selective inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 2110–2124. 10.1021/jm3018332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaniskan H.Ü.; Szewczyk M. M.; Yu Z.; Eram M. S.; Yang X.; Schmidt K.; Luo X.; Dai M.; He F.; Zang I.; Lin Y. A potent, selective and cell-active allosteric inhibitor of protein arginine methyltransferase 3 (PRMT3). Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 5166–5170. 10.1002/anie.201412154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaniskan H. U.; Eram M. S.; Zhao K.; Szewczyk M. M.; Yang X.; Schmidt K.; Luo X.; Xiao S.; Dai M.; He F.; Zang I. Discovery of potent and selective allosteric inhibitors of protein arginine methyltransferase 3 (PRMT3). J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 1204–1217. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SGC6870 A chemical probe for PRMT6. Retrieved (2020-01-07) from https://www.thesgc.org/chemical-probes/SGC6870.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.