The unprecedented speed and scale of spread of the global COVID-19 pandemic has forced policy-makers and clinicians to operate with limited evidence for the relative success of different control measures. In the words of Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte, ‘with 50% of the knowledge we have to make 100% of the decisions’.1 Understanding mortality differences will be a key factor in distinguishing the relative effectiveness of prevention and control measures between countries,2 but as we discuss, comparisons are affected by differences in reporting and testing. Excess mortality can overcome this inherent variation, but without appreciation of its constituent parts, its role in helping us understand why mortality differs between countries remains limited.

Throughout the pandemic, ‘league tables’ have tracked cases and deaths globally. Although these figures quantify the overall scale of disease within a country, they are limited as comparative measures by differences in factors such as population size and demographics. As of 31 July 2020, the USA has the highest number of total COVID-19 deaths, but relative to population size, of countries with at least 100 COVID-19 deaths, the USA ranks eighth, while Belgium has the highest COVID-19 mortality.3 Demographic differences also add to the complexity in drawing comparisons. Increasing age is strongly associated with COVID-19 mortality, and the population age distributions within countries may be very different, impacting on the comparability of COVID-19 statistics between countries.

Limitations to COVID-19 mortality estimates: reporting and testing

Although we can adjust or standardise for these factors, comparisons of COVID-19 mortality remain limited unless we understand how definitions of a death vary. The World Health Organization defines a COVID-19 death as one where COVID-19 is the underlying cause of death, encompassing both confirmed and suspected cases.4 Where COVID-19 is a contributing factor, but not the cause leading directly to death, it is not counted. However, the World Health Organization guidance was introduced in April 2020, by which stage countries may already have introduced their own guidance. Consequently, there are significant differences in how COVID-19 deaths are reported between countries.5

Russia’s case definition for a COVID-19 death, for example, relies solely on results from autopsy, unlike most European countries.6 Death must have been due directly to COVID-19, so it is not counted if a patient was found to have COVID-19 but it did not cause their death.6,7 This will lead to significant underreporting, especially as Russia has one of the highest numbers of COVID-19 cases worldwide and yet has a case fatality rate of only 1.7% as of 31 July 2020.3 Spain’s definition requires a positive polymerase chain reaction or antibody test for COVID-19, with only hospital deaths included in the death count despite a significant number of deaths from COVID-19 in the community and care homes.8,9 Belgium, by contrast, has one of the broadest definitions for a COVID-19 death, including all suspected cases. Care home deaths in Belgium account for around half of all excess deaths, but only 26% of care home deaths were confirmed (rather than suspected) COVID-19,10 leading to possible overcounting relative to other countries.11 Criteria may also differ within country. In the UK, for example, the Department of Health and Social Care and National Health Service England report COVID-19 deaths where the person tested positive, whereas the Office for National Statistics additionally include cases where COVID-19 is mentioned anywhere on a death certificate.12

Availability of, and criteria for, testing will also affect the number of COVID-19 deaths, particularly where only confirmed cases are included. At the start of the pandemic, no ‘off-the-shelf’ method of diagnosing COVID-19 infection was readily available. In the UK, for example, availability of diagnostic tests was limited to hospital settings in March 2020, and reserved for the most unwell, with community testing largely being stopped; however, over time testing has been extended as testing capacity has increased.13 For weeks into the pandemic, particularly outside of the hospital, many patients who died with clinical features consistent with COVID-19 infection will have gone untested. Whether, in the absence of testing, clinicians overestimate or underestimate COVID-19 as a cause of death during the pandemic is unknown, but both are equally plausible. There is wide variation in clinical decision-making and in how doctors complete death certificates based on personal, professional and contextual factors.14 There may be many deaths misattributed to COVID-19 and, conversely, others not attributed to COVID-19 where it was the underlying cause, contributing to uncertainty surrounding the true number of COVID-19 deaths.

Excess mortality

As the pandemic has progressed, there has been a growing focus on excess mortality as a more reliable metric for comparing countries.15 Excess mortality provides an estimate of the additional number of deaths within a given time period in a geographical region (e.g. country), compared to the number of deaths expected (often estimated using the same time period in the preceding year or averaged over several preceding years).15 In encompassing deaths from all causes, excess mortality overcomes the variation between countries in reporting and testing of COVID-19 and in the misclassification of the cause of death on death certificates. Under the assumption that the incidence of other diseases remains steady over time, then excess deaths can be viewed as those caused both directly and indirectly by COVID-19 and gives a summary measure of the ‘whole system’ impact. Excess mortality can also be standardised for age or population size to aid comparability between countries.

Beyond excess mortality

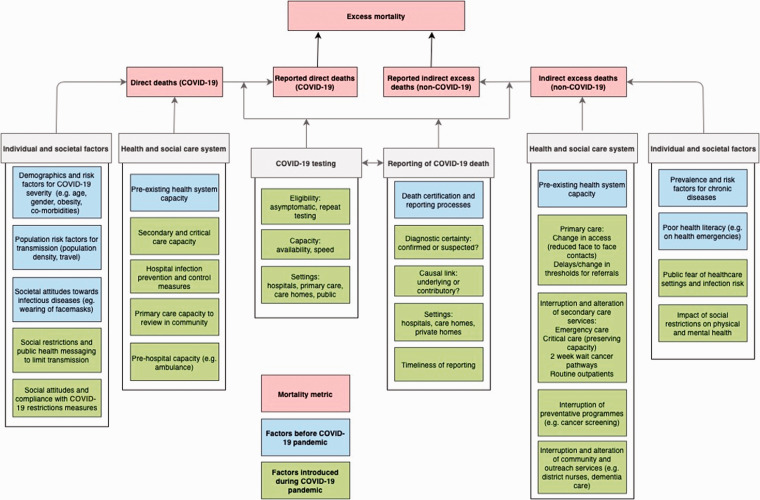

Despite this, when seeking to understand the full impact of deaths due to COVID-19 and explain why excess deaths vary, there is a need to distinguish the component parts – of direct COVID-19 and indirect, non-COVID-19 deaths. Figure 1 summarises the multiple factors impacting on COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 deaths during the pandemic, ranging from individual risk factors and attitudes to restriction measures, to public health policies and changes to health systems. Individual fears of contracting the disease or of overburdening the system may alter health-seeking behaviours and lead to increased deaths from non-COVID-19 causes: for example, the number of patients presenting with heart attacks and stroke has declined in the USA during the outbreak.16,17 Urgent referrals for suspected cancer have fallen in the many countries,18 which may reflect a decrease in patients presenting with ‘red flag’ symptoms or changes to clinician thresholds for referral due to health system pressures, leading to both short- and long-term impacts on indirect mortality.19 Overburdening of the health system and changes to clinical pathways as a response to prioritising COVID-19 cases may leave deficiencies in standard care pathways.19 Globally, the World Health Organization has found that 42% of countries have experienced disruptions to cancer services, 49% for diabetes and 31% for cardiovascular disease services.20 Concerns about the efficacy of the pandemic response will arise if deaths from COVID-19 are limited only at the expense of deaths from other causes. Excess mortality has limitations in explaining differences between countries; and in understanding why excess mortality differs, we must differentiate the cause of death.

Figure 1.

Factors impacting on excess mortality, COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 excess deaths.

Variation between countries

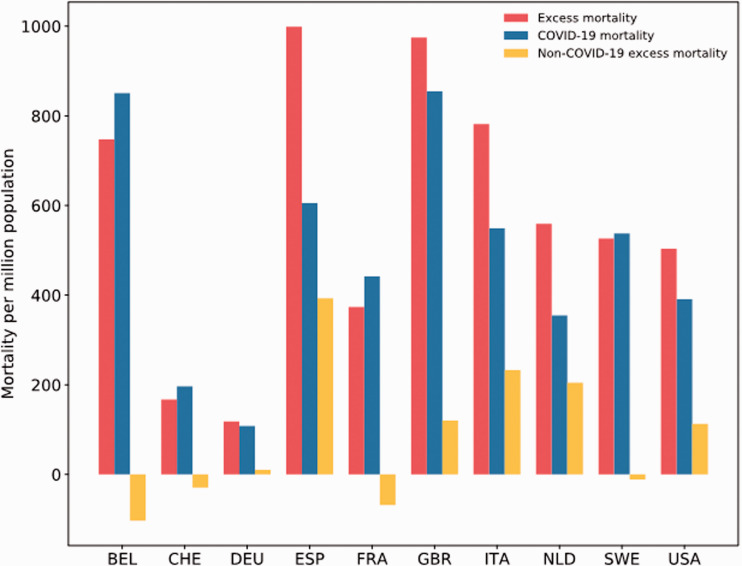

There is significant variation in total excess deaths, and in the relative contributions from COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 excess deaths between countries, as shown in Figure 2. Data on weekly all-cause deaths and COVID-19 deaths were sourced from the Human Mortality Database21 and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control3 (Office for National Statistics for England and Wales22), respectively. We selected the 10 countries with the highest total COVID-19 deaths of those with data on all-cause deaths. Cumulative excess deaths were calculated as the number of deaths per week in 2020 minus the number of deaths per week averaged across 2015–2019 (2016–2019 for Germany) starting from the week of the first reported COVID-19 death. Non-COVID-19 deaths were calculated as the number of excess deaths minus the number of COVID-19 deaths. Figures are reported as counts per million to account for population size. Reporting time frames are not uniform across countries, and data were censored when mortality fell below 90% of the historic average to account for possible reporting delays.

Figure 2.

Total excess deaths with relative contribution of COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 excess deaths per million population for 10 countries.

Note. Data on weekly mortality from the Human Mortality Database.21 COVID-19 deaths from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.3 COVID-19 deaths for England and Wales from the Office for National Statistics.22

BEL: Belgium; CHE: Switzerland; DEU: Germany; ESP: Spain; FRA: France; GBR: England and Wales; ITA: Italy; NLD: Netherlands; SWE: Sweden; USA: United States of America.

The highest excess mortality per million population is seen in Spain, followed by England and Wales. The majority of these excess deaths are caused by COVID-19, but a significant proportion of 39% in Spain are not directly related to COVID-19. Data from Belgium, France and Switzerland suggest that non-COVID-19 deaths could be lower than expected. This may reflect the broader case definition for COVID-19 deaths in Belgium, resulting in some non-COVID-19 deaths being misclassified as COVID-19 deaths. In the case of France, following the peak of the pandemic in April, mortality from 1 to 18 May 2020 was 6% lower than in the same period in 2019, with larger reductions in mortality in younger age groups.23 Although this may represent delays in reporting of deaths, rather than a genuine decline in non-COVID-19 deaths, analyses from the Office for National Statistics have shown a similar effect in many European countries: by the end of May, cumulative mortality returned to expected levels, or even lower-than-expected levels, particularly in the under-65 s.24

Some vulnerable individuals who died of COVID-19 might otherwise have died from alternate causes, a concept known as ‘mortality displacement’. Short-term increases in mortality due to COVID-19 may result in a relative reduction in mortality from other causes in subsequent weeks and a gradual fall in total excess mortality over time. However, mortality displacement is unlikely to explain the falls in mortality in younger age groups where mortality from COVID-19 is low. Factors such as a lowering of air pollution during the pandemic may have had positive impacts on mortality.25 Deaths from suicide, injury and poisoning are the leading causes of death in younger adults in England and Wales, and social restrictions may have led to falls in deaths from these causes.26 However, registration of these deaths can take many months, often following a coroner’s inquest, so it will be some time before we understand whether any suspected reductions in mortality in younger people are real.27

In the UK, the Office for National Statistics has begun to investigate the causes of non-COVID-19 excess deaths.27 Up until 1 May 2020, 28% of excess deaths did not involve COVID-19, with significant numbers of non-COVID-19 deaths occurring in care homes or in private homes, and a corresponding decline in non-COVID-19 excess deaths in hospitals. Dementia, along with old age and frailty, was among the most common causes of non-COVID-19 deaths. A recent study of deaths in four UK care homes found that 43% of residents testing positive for COVID-19 had no symptoms in the two weeks before death, and 18% had atypical symptoms only, suggesting that identification of disease may be more difficult in this setting and that some COVID-19 deaths have gone unrecognised.28 Social isolation in older adults is known to be associated with increased all-cause mortality,29 and the social restrictions imposed to limit transmission may have had the unintended effect of increasing mortality from non-COVID-19 causes in this age group.

Measuring the impact of COVID-19: beyond mortality statistics

In measuring the impact of COVID-19 and considering control strategies, mortality is only one of many factors. Even in ‘mild’ cases not requiring hospitalisation, symptoms can be long-lasting, and pulmonary30 and cardiac31 complications are common, affecting quality of life and ability to work. The enforcement of social restrictions may have negative health consequences, with mental health problems increasing during the pandemic.32 Beyond the effects on health, the pandemic has disrupted all aspects of society – many countries have experienced record economic recessions, while school closures may impact children’s educational attainment. Mortality, and, specifically, excess mortality, should not therefore be used as the only measure of the impact of COVID-19.

Using excess mortality to inform policy

Usefully comparing COVID-19 mortality between different countries requires systems that are standardised, a significant shift from the status quo. To harness the potential of excess mortality in informing and guiding pandemic responses, data must be timely and comprehensive, including out-of-hospital deaths and reporting of all causes of deaths. Where countries have robust systems to collect this data, they should be reported, ideally in real time, to show trends within country. Further in-depth reporting such as that from the Office for National Statistics in the UK is urgently needed for all nations impacted by COVID-19. This will allow a robust assessment of the direct and indirect impact and help to guide national or local public health policy. It will also allow comparison of the effectiveness of different control, suppression and mitigation policies, which in turn will allow countries to prepare better for a second wave of infection or a future pandemic from a different pathogen. Experience to date suggests that countries that responded rapidly to implement suppression measures, such as South Korea, have fared considerably better than the UK.33

Conclusion

Excess mortality is a measure that encompasses all causes of death and provides a metric of the overall mortality impact of COVID-19. When seeking to draw comparisons between countries, it is necessary to understand why mortality varies, through disentangling the constituent parts – of direct COVID-19 deaths and indirect, non-COVID-19 excess deaths – and there is urgent need for national bodies to report all-cause mortality. Where data collection and reporting systems are timely and comprehensive, excess mortality, used alongside cause-specific mortality, can be useful to monitor trends within and between countries and inform international, national and local public health policies.

Declarations

Competing Interests

None declared.

Funding

TB, VJ and DS are supported by National Institute for Health Research Academic Clinical Fellowships. AM is supported by the National Institute for Health Research Northwest London Applied Research Collaboration Programme. The views expressed in the article are those of the authors.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Guarantor

TB.

Contributorship

TB conceived the article and undertook analyses using routinely available data. VJ, JMC and TB created the figures. All authors contributed to the drafting and revision of the manuscript and approved the final submission.

Provenance

Not commissioned; peer-reviewed by Frank Lichtenberg and Graham Kirkwood.

Acknowledgements

None.

References

- 1.Lodge M and Boin A. Making Sense of an Existential Crisis: The Ultimate Leadership Challenge | LSE Government Blog. See https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/government/2020/03/26/making-sense-of-an-existential-crisis-the-ultimate-leadership-challenge/ (last checked 10 June 2020).

- 2.Pearce N, Lawlor DA and Brickley EB. Comparisons between countries are essential for the control of COVID-19. Int J Epidemiol. Epub ahead of print 29 June 2020. DOI: 10.1093/ije/dyaa108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Geographic Distribution of Covid-19 Cases Worldwide as of 31 July 2020. See https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/download-todays-data-geographic-distribution-covid-19-cases-worldwide (last checked 31 July 2020).

- 4.World Health Organization. International Guidelines for Certification and Classification (Coding) of COVID-19 as Cause of Death Based on ICD International Statistical Classification of Diseases. See https://www.who.int/classifications/icd/Guidelines_Cause_of_Death_COVID-19-20200420-EN.pdf (last checked 10 June 2020).

- 5.International Observatory of Human Rights. China, Russia, Brazil and the Underreporting of Covid-19 Cases. See https://observatoryihr.org/news/china-russia-brazil-and-the-underreporting-of-covid-19-cases/ (last checked 10 June 2020).

- 6.Reuters. Russia Says Many Coronavirus Patients Died of Other Causes. Some Disagree. See https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-russia-casualties/russia-says-many-coronavirus-patients-died-of-other-causes-some-disagree-idUSKBN22V1Q7 (last checked 16 June 2020).

- 7.The New York Times. A Coronavirus Mystery Explained: Moscow Has 1,700 Extra Deaths. See https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/11/world/europe/coronavirus-deaths-moscow.html (last checked 16 June 2020).

- 8.EL PAÍS. Coronavirus Crisis in Spain: Spain’s Coronavirus Crisis: Why the Numbers Are Failing to Show the Full Picture. See https://english.elpais.com/society/2020-04-05/spains-coronavirus-crisis-why-the-numbers-are-failing-to-show-the-full-picture.html (last checked 18 June 2020).

- 9.Catalan News. Why Is Spain as a Whole Reporting Fewer New Covid-19 Deaths Than Catalonia? See https://www.catalannews.com/society-science/item/why-is-spain-as-a-whole-reporting-fewer-new-covid-19-deaths-than-catalonia (last checked 15 June 2020).

- 10.Federal Public Service (FPS) Health Food Chain Safety and Environment. Coronavirus COVID-19: Latest News: 12-06-2020: 108 New Infections. See https://www.info-coronavirus.be/en/news/108-new-infections/ (last checked 16 June 2020).

- 11.Deutsche Welle. Belgium’s Coronavirus (Over)Counting Controversy. See https://www.dw.com/en/belgiums-coronavirus-overcounting-controversy/a-53660975 (last checked 16 June 2020).

- 12.Raleigh V. Deaths from Covid-19 (coronavirus): how are they counted and what do they show? The King’s Fund. See https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/deaths-covid-19 (last checked 16 June 2020).

- 13.NHS Providers. 2020: Coronavirus Briefing 19 May Spotlight on Recent NHS Discharges Into Care Homes. See https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8302039/Hospitals-probed-sending-elderly-care-homes- (last checked 16 June 2020).

- 14.Crowcroft N, Majeed A. Improving the certification of death and the usefulness of routine mortality statistics. Clin Med 2001; 1: 122–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krelle H, Barclay C and Tallack C. Understanding excess mortality: what is the fairest way to compare COVID-19 deaths internationally? The Health Foundation. See https://www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/charts-and-infographics/understanding-excess-mortality-the-fairest-way-to-make-international-comparisons (last checked 16 June 2020).

- 16.Solomon MD, McNulty EJ, Rana JS, Leong TK, Lee C, Sung S, et al. The Covid-19 pandemic and the incidence of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 691--693. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Kansagra AP, Goyal MS, Hamilton S and Albers GW. Collateral effect of Covid-19 on stroke evaluation in the United States. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 400--401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Richards M, Anderson M, Carter P, Ebert BL, Mossialos E. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer care. Nat Cancer 2020; 1: 565–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai A, Pasea L, Banerjee A, Denaxas S, Katsoulis M, Chang WH, et al. Estimating excess mortality in people with cancer and multimorbidity in the COVID-19 emergency. medRxiv. Epub ahead of print 29 April 2020. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.34254.82242.

- 20.World Health Organization. COVID-19 Significantly Impacts Health Services for Noncommunicable Diseases. See https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/01-06-2020-covid-19-significantly-impacts-health-services-for-noncommunicable-diseases (last checked 16 June 2020).

- 21.Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Germany) and University of California Berkeley (USA). Human Mortality Database: Short-Term Mortality Fluctuations (STMF) Data Series. See https://www.mortality.org (last checked 31 July 2020).

- 22.Office for National Statistics. Deaths Registered Weekly in England and Wales, Provisional. 2020: Up To Week Ending 17 July 2020. See https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/datasets/weeklyprovisionalfiguresondeathsregisteredinenglandandwales (last checked 31 July 2020).

- 23.Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques. Number of Daily Deaths: Evolution of Deaths Since 1 May 2020. See https://www.insee.fr/en/statistiques/4493806?sommaire=4493845 (last checked 31 July 2020).

- 24.Office for National Statistics. Comparisons of All-Cause Mortality Between European Countries and Regions: January to June 2020. See https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/articles/comparisonsofallcausemortalitybetweeneuropeancountriesandregions/januarytojune2020 (last checked 3 August 2020).

- 25.Chen K, Wang M, Huang C, Kinney PL, Anastas PT. Air pollution reduction and mortality benefit during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Lancet Planet Health 2020; 4: e210–e212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Office for National Statistics. Deaths Registered in England and Wales: 2019. See https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsregistrationsummarytables/2019 (last checked 3 August 2020).

- 27.Office for National Statistics. Analysis of Death Registrations Not Involving Coronavirus (COVID-19), England and Wales: 28 December 2019 to 1 May 2020. See https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/articles/analysisofdeathregistrationsnotinvolvingcoronaviruscovid19englandandwales28december2019to1may2020/technicalannex (last checked 16 June 2020).

- 28.Graham NSN, Junghans C, Downes R, Sendall C, Lai H, McKirdy A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection, clinical features and outcome of COVID-19 in United Kingdom nursing homes. J Infect 2020; 81: 411–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elovainio M, Hakulinen C, Pulkki-Råback L, Virtanen M, Josefsson K, Jokela M, et al. Contribution of risk factors to excess mortality in isolated and lonely individuals: an analysis of data from the UK Biobank cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2017; 4: e260–e266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao Y, Shang Y, Song W, Li Q, Xie H, Xu Q, et al. Follow-up study of the pulmonary function and related physiological characteristics of COVID-19 survivors three months after recovery. EClinicalMedicine. Epub ahead of print 3 August 2020. DOI: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Puntmann VO, Carerj ML, Wieters I, Fahim M, Arendt C, Hoffmann J, et al. Outcomes of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in patients recently recovered from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. Epub ahead of print 27 July 2020. DOI: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Daly M, Sutin A and Robinson E. Longitudinal changes in mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from the UK household longitudinal study. PsyArXiv. See https://psyarxiv.com/qd5z7/ (last checked 3 August 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Majeed A, Seo Y, Heo K, Lee D. Can the UK emulate the South Korean approach to Covid-19? BMJ 2020; 369: m2084–m2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]