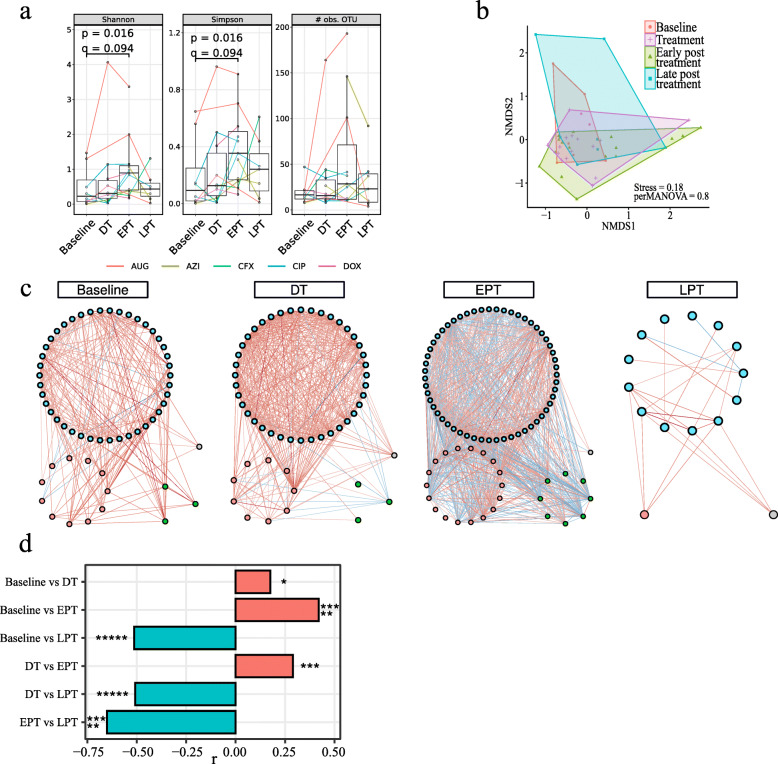

Fig. 1.

Antibiotic treatment induces fungal competition. Statistical testing by Wilcoxon signed-rank tests with p values adjusted for multiple testing using false discovery rate (FDR) (q = FDR[p]). Not significant, ns: q ≥ 0.05; *q < 0.05; **q < 0.01; ***q < 1e− 3; ****q < 1e− 4; *****q < 1e− 5. a, b Diversity analysis of samples from treated participants using PIPITS operational taxonomic units (OTU) relative abundances. a Boxplots showing Shannon (left) and Gini-Simpson indexes (middle) and species richness (right) with median (centerlines), first and third quartiles (box limits), and 1.5× interquartile range (whiskers). No significant changes were observed (q < 0.05). b Non-metric dimensional scaling of Bray-Curtis distance as a measure of beta diversity. No significant differences (p < 0.05) were found between time points using PERMANOVA. c, d Co-abundance network analysis using BAnOCC. Only OTUs with prevalence 10% and significant correlations (95% credibility interval) with |r| ≥ 0.3 were used for network construction. Networks were created independently for baseline, during (DT), early post (EPT), and late post treatment (LPT) to show temporal changes in fungal communities. c Fungal networks. Node colour indicates fungal phyla. Blue, Ascomycota; red, Basidiomycota; green, Mucoromycotina; grey, unknown. Edge colour indicates correlation type. Red, positive; blue, negative. d Network properties. Bar plots show number of nodes that increased and decreased in node degree centrality