Abstract

Thymoquinone (TQ), a natural anticancer agent exerts cytotoxic effects on several tumors by targeting multiple pathways, including apoptosis. Difluoromethylornithine (DFMO), an irreversible inhibitor of the ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) enzyme, has shown promising inhibitory activities in many cancers including leukemia by decreasing the biosynthesis of the intracellular polyamines. The present study aimed to investigate the combinatorial cytotoxic effects of TQ and DFMO on human acute T lymphoblastic leukemia Jurkat cells and to determine the underlying mechanisms. Here, we show that the combination of DFMO and TQ significantly reduced cell viability and resulted in significant synergistic effects on apoptosis when compared to either DFMO or TQ alone. RNA-sequencing showed that many key epigenetic players including Ubiquitin-like containing PHD and Ring finger 1 (UHRF1) and its 2 partners DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) and histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) were down-regulated in DFMO-treated Jurkat cells. The combination of DFMO and TQ dramatically decreased the expression of UHRF1, DNMT1 and HDAC1 genes compared to either DFMO or TQ alone. UHRF1 knockdown led to a decrease in Jurkat cell viability. In conclusion, these results suggest that the combination of DFMO and TQ could be a promising new strategy for the treatment of human acute T lymphoblastic leukemia by targeting the epigenetic code.

Keywords: thymoquinone, DFMO, apoptosis, gene expression, epigenetics

Introduction

Alpha-Difluoromethylornithine (DFMO) is a potent, selective irreversible inhibitor of a critical regulatory polyamine biosynthetic enzyme-Ornithine decarboxylase (ODC). Endogenous polyamines like Putrescine, Spermidine and Spermine, are synthesized in all the eukaryotic cells at micromolar concentrations. These polyamines are crucial for the normal cell growth, differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis and maintenance of cells.1 However, in tumor cells, the enzyme ODC is highly upregulated leading to the manifold increase in the intracellular concentration of the polyamines.2 Several studies have shown that DFMO exerts inhibitory effects on different cancers such as skin cancer,3 breast cancer,4 leukemia,5 prostate cancer6 and pancreatic cancer.7 The regulation of polyamine metabolism by DFMO has been a target in many previous studies8,9 in addition to cancer investigations. DFMO generally exhibits cytostatic effects, but the excitement was escalated when some cytotoxic effect was observed in promyelocytic leukemia and other cancers.10,11 However, the use of DFMO as a single anti-proliferative agent resulted in ototoxicity12,13 or showed ineffectiveness; attributed in large part to the increased intake of extracellular polyamines via a polyamine transport system.14 Hence, to overcome this limitation, many researchers have suggested combination therapy based on the regulation of polyamine metabolism and enzyme inhibition to devise an effective neoplastic strategy.15,16 Indeed, DFMO has been used in low doses in combination with other anticancer agents5 in the treatment of several tumors including leukemia.5 In tumor therapy, the inhibitory effects of DFMO involve a complex interplay between the polyamine levels, ODC activity and the expression of several oncogenes.17 Many preclinical studies are still in progress which could unravel some essential mechanistic insights of the synergistic effect of DFMO and other anticancer agents. In this context, combining DFMO at low doses with Sunlidac has markedly reduced the recurrences of adenomatous polyps.18

Thymoquinone (TQ) is the most biologically active ingredient of volatile oil extracted from black cumin (N. sativa) seeds.19,20 TQ has been intensively investigated for its anticancerous, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, antihypertensive, antioxidant and hepatoprotective properties.21,22 TQ has been shown to induce apoptosis in leukemia cells involving the downregulation of UHRF1 (Ubiquitin-like containing PHD and Ring Finger 1), DNMT1 (DNA methyltransferase 1), HDAC1 (histone deacetylase 1) and the upregulation of the tumor suppressor gene p16INK4A 23,24 which is epigenetically silenced in acute lymphocytic leukemia.25,26 Other studies have shown the anticancer efficacy of TQ in combination with other drugs in cancer cells such as Cisplatin, Tamoxifen, Docetaxel and 5-fluorouracil.27,28 All these works highlighted the increased importance of combining TQ with other anticancer drugs at low doses to provide both significant efficacy and safety for cancer therapy.

The current study aimed to investigate, whether DFMO and TQ work synergistically to induce apoptosis in human acute T lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) Jurkat cells and to determine the underlying mechanism. In the present study, we found that the combination of DFMO and TQ resulted in significant synergistic effects on cell viability and apoptosis when compared to either DFMO or TQ alone most likely through targeting the epigenetic integrator UHRF1 and its 2 partners DNMT1 and HDAC1.

Materials and methods

Cell Culture and Treatment

The acute T lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) Jurkat cell line was procured from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). The cell line was maintained at 5% CO2 and 37°C in a humidified incubator. For optimal cell growth, Jurkat cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (UFC Biotech, Riyadh, KSA) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (GibcoTM) and 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin (GibcoTM). TQ and DFMO were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich.

Cell Proliferation and Cell Viability Assays

The cytotoxic activity of the TQ and DFMO on tumor cells was evaluated through a rapid coulometric cell proliferation assay using WST-1 reagent (Sigma Aldrich, USA). Jurkat cells were plated at 4 x 104 cells per well and incubated for 24 h in a clear flat bottom 96 well plate. Then, the cells were treated with desired concentrations of either DFMO /TQ or both. After incubation for different periods, WST-1 solution (10 µL) was added to wells and incubated for at least 3 h at 37°C. Finally, the absorbance was recorded at 450 nm with an ELx800™ microplate ELISA reader (Biotek, USA) and the results were analyzed by the Gen5 software (Biotek, USA). The percentage of cell viability was calculated by assuming control (untreated) samples as 100% viable. Jurkat cell viability rate was also determined by cell counting using the trypan blue exclusion method (Invitrogen). The viability rate was obtained by dividing the number of trypan blue-negative cells (living cells) by the total number of cells (dead and living cells).

Annexin V/7-AAD Assay

To study the apoptosis in Jurkat cells, the Annexin V Binding Guava Nexin® (Guava Easycyte Plus HP system) was used according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. In brief, after the desired treatment conditions, the nexin reagent containing annexin V-fluorescein and 7AAD was added (100 µL) and incubated for 20 mins in the dark at room temperature. This assay utilizes dual markers (Annexin V-PE and 7-AAD) to determine the apoptosis rate. The viable cells are negative for both markers and the cells which are positive for Annexin V but negative for 7-AAD are early apoptotic. In contrast, the cells which are positive for both the markers are classified as late apoptotic or necrotic cells. InCyteTM software (Millipore®, Billerica, Massachusetts, USA) was used to plot the results. The forward and side scatter (FSC and SSC) were recorded at 10,000 events for each analysis.

RNA-Seq and Differentially Expressed Genes analysis

Jurkat cells were treated with DFMO at 1 mM for 24 h in triplicates, then RNA-seq was carried out as described elsewhere.29 Briefly, Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy kit Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA, and the RNA concentration was quantified. The 50-bp (base pair) long single-end deep sequencing was performed using Illumina HiSeq 2000 system. The obtained filtered short sequencing reads were mapped to the human genome using TopHat2, and the subsequent gene expression values were quantified using Subreads package Feature Counts function. The differentially expressed gene (DEG) analysis was further performed from the gene expression values after identifying the library size, and appropriate data set dispersion. Differentially expressed genes are determined by log2 fold change (Log2FC) and false discovery rate (FDR; log fold change [LogFC] ⩾0.5 or ⩽−0.5; FDR ⩽ 0.05).

Reverse Transcription and Real-time PCR

The total RNA was isolated and purified from Jurkat cells using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). The cDNA libraries were created from the RNA (Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase, Invitrogen) by using specific primers and Real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Green qPCR (iQ SUPERMIX, BioRad) on ABI7500 system. The qPCR conditions were maintained at 95°C, 30 sec; 60°C, 40 sec; 72°C, 40 sec. The sequences of the primers used for the PCR amplification were: UHRF1 (sense: 5′GTCGAATCATCTTCGTGGAC3′; antisense:5′AGTACCACCTCGCTGGCA 3′); DNMT1(sense:5′GGCCTTTTCACCTCCATCAA3′;antisense:5′GCACAAACTGACCTGCTTCA3′); HDAC1(sense:5′GCTTGCTGTACTCCGACATG-3′;antisense: 5′-GACAAGGCCACCCAATGAAG-3′); GAPDH (sense: 5′- GGTGAAGGTCGGA-GTCAAC-3′, antisense: 5′-AGAGTTAAAAGC-AGCCCTGGTG-3′). The results were normalized to those obtained with GAPDH mRNA.

Western blot Analysis

Jurkat cells were transfected with UHRF1 siRNA for 72 h. The cells were then harvested, centrifuged to discard the medium. After washing with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the cells were resuspended in RIPA buffer (25 mM Tris, pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate and 0.1% SDS; Sigma-Aldrich, St-Louis, MO, USA) containing protease inhibitors and incubated on ice for 15 min. Cell suspensions were sonicated 3 times for 30 sec each 5 min and then were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and the protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad, Marne la Coquette, France). Equal amounts of total protein were taken. After adding Laemmli sample buffer containing 5% mercaptoethanol, protein samples were placed in a water bath at 100°C for 10 min. The proteins were separated on 12% SDS-PAGE and electrophoretically transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane followed with blocking with 5% bovine serum albumin and tween 20 in PBS. The membranes were then incubated with a mouse monoclonal anti-UHRF1 (Proteogenix, Oberhausbergen, France), or mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody (Abcam, Paris, France) according to the manufacturer’s instructions at 4°C overnight. After washing 3 times for 10 min each with PBS, the membranes were thereafter incubated with anti-mouse antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA) at 1:10000 dilution for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were then washed with PBS 5 times. Signals were detected by chemiluminescence using the ECL Plus detection system (Amersham, GE Healthcare UK).

siRNA Transfection

Jurkat cells were transfected with UHRF1 siRNA as previously described.30 The sequence of the siRNA for UHRF1 was 5′-GGUCAAUGAGUACGUCGAUdTdT-3′ (corresponding to nucleotides 408–426 relative to the start codon). The sequence of the scramble siRNA for UHRF1, designed by and obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, was 5′-GGACUCUCGGAUUGUAAGAdTdT-3′. Transfections were performed using lipofectamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The experiments were carried out on cells 72 h after siRNA (100 pmol) transfections at 0, 24 and 48 h.

Statistical Analysis

For the comparison of the multiple groups, the statistical analysis was performed using one way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test using GraphPad Prism 6 software (GraphPad, San Diego, USA) and the significant differences were indicated as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and ****P < .0001. The differences between the control and the treated were analyzed by Student’s t-test (2-tailed) and the significant differences were indicated as ##, p < 0.01, ###, p < 0.001, ####, p < 0.0001 or &&, p < 0.01, &&&, p < 0.001, &&&&, p < 0.0001 versus respective control.

Results

Cytotoxic Effect of TQ and/or DFMO on Jurkat Cells

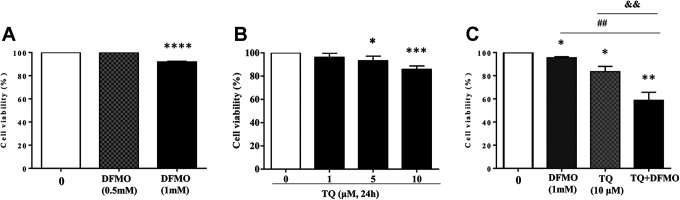

Initially, we evaluated the cytotoxic effect of either DFMO or TQ on Jurkat cell viability by WST-1 staining (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effect of Thymoquinone and/or DFMO on Jurkat cell viability. Cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of DFMO (A) or TQ (B) for 24 h. To evaluate the synergistic effect on cell viability, cells were treated with either DFMO (1 mM) for 48 h or TQ (10 μM) or incubated with 1 mM of DFMO for 24 h before adding 10 μM of TQ for additional 24 h (C). Cell viability rate was assessed by WST-1 assay, as indicated in the methods and materials. The data are representative of 3 different experiments. Values are shown as means ± S.E.M. (n = 3); *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001, ****, p < 0.0001, ##, p < 0.01, &&, p < 0.01 versus respective control.

Data obtained from 24 h treatment of Jurkat cells showed that DFMO did not affect cell viability at a concentration of 0.5 mM (Figure 1A). However, when the level of DFMO was increased to 1 mM, the cell viability was significantly reduced to 92% (Figure 1A). Our previous findings using MTS and trypan blue assays have shown that TQ decreased Jurkat cell viability in a dose-dependent mechanism.23 We further explored the effect of different concentrations of TQ on Jurkat cell viability using WST-1 staining for 24 h of treatment (Figure 1B). As expected, TQ showed a significant decrease in the cell viability starting from 5 µM (93%) and reached 85.8% at 10 µM (Figure 1B). However, Jurkat cell viability was reduced to 95.4% and 83.4% using DFMO (1 mM) and TQ (10 µM) respectively (Figure 1C). Interestingly, the combination of both the drugs under similar experimental conditions resulted in drastic cell viability reduction which reached to 58.7% (Figure 1C) indicating that TQ and DFMO exhibit true synergism to inhibit Jurkat cell viability which could be due to the improvement of the pro-apoptotic effect of both the drugs.

Pro-Apoptotic Effect of TQ and/or DFMO on Jurkat Cells

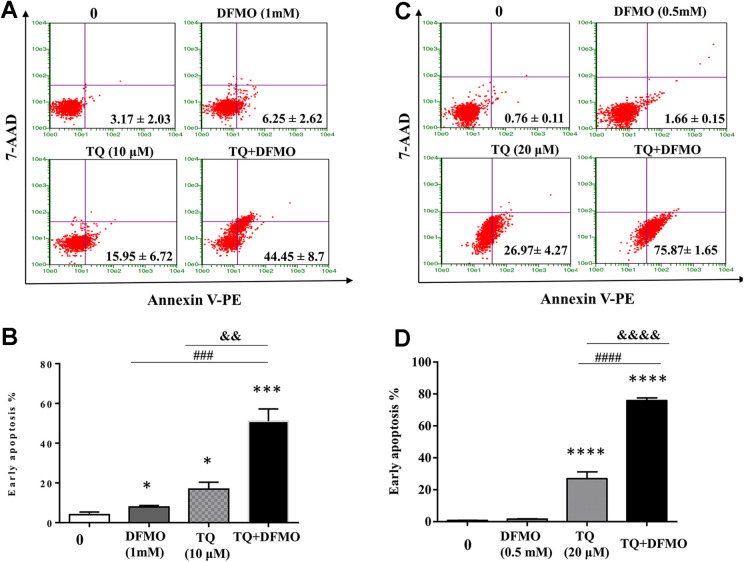

To study the hypothesis that TQ and DMFO synergize to induce apoptosis in Jurkat cells, we performed annexin V staining to detect the apoptosis stages in Jurkat cells treated with individual TQ or DFMO drug as well as in combination. The data obtained from annexin V staining of Jurkat cells showed that apoptotic rate was significantly increased to 8% in DFMO at 1 mM (P < 0.05) and to 16.8% (P < 0.05) using TQ at 10 µM. Interestingly, the combination of 2 drugs significantly increased the percentage of early apoptotic cells to 44.45 ± 8.7% (P < 0.001) (Figure 2A and B) suggesting a synergistic effect of TQ and DFMO on apoptosis of Jurkat cells. To confirm the synergistic effect of TQ and DFMO on apoptosis of Jurkat cells, we also performed annexin V staining to detect the apoptosis stages in Jurkat cells treated with individual TQ or DFMO drug as well as in combination using DFMO at a concentration of 0.5 mM (which DFMO did not affect cell viability as shown in Figure 1) and TQ at a concentration of 20 µM. The data obtained showed that DFMO at a concentration of 0.5 mM did not induce apoptosis while the early apoptotic rate was significantly increased to 26.97 ± 4.27% (P < 0.001) using TQ at 20 µM. Interestingly, the combination of 2 drugs significantly increased the percentage of early apoptotic cells to 75.87 ± 1.65% (P < 0.001) (Figure 2C & D) confirming the synergistic effect of TQ and DFMO on apoptosis of Jurkat cells.

Figure 2.

DFMO and Thymoquinone synergize to induce apoptosis in Jurkat cells. To evaluate the synergistic effect on apoptosis, cells were treated with either DFMO at 1 mM for 48 h or TQ at 10 μM or incubated with 1 mM of DFMO for 24 h before adding TQ at (10 μM) for additional 24 h (A & B). To confirm the synergistic effect of TQ and DFMO, cells were treated with either DFMO at 0.5 mM for 48 h or TQ at 20 μM or incubated with 0.5 mM of DFMO for 24 h before adding TQ at (20 μM) for additional 24 h. Apoptosis in Jurkat cells was assessed by flow cytometry using the Annexin V/7AAD staining apoptosis assay (A, B, C & D). Values are shown as means ± S.E.M. (n = 3); *, p < 0.05, ***, p < 0.001, ****, p < 0.0001, ###, p < 0.001, ####, p < 0.0001, &&, p < 0.01, &&&&, p < 0.0001 versus respective control.

Pro-Apoptotic Effects of DFMO Involve Regulation of Several Epigenetic Pathways

Our previous study showed that the TQ-induced apoptosis in Jurkat involves the modulations of several writer and readers. To evaluate whether DFMO can also induce apoptosis in the same way as TQ, we analyzed the gene expression in Jurkat incubated for 24 h with 1 mM of DFMO. Then, RNA-Seq was done using next-generation sequencing as described in Materials and Methods. RNA-Seq data showed that the epigenetic integrator UHRF1, HDAC4 and DNMT1 were significantly down-regulated in DFMO-treated Jurkat cells (Table 1).

Table 1.

Downregulated Genes Triggered in DFMO-Treated Jurkat Cells as Compared with Untreated Cells.

| Gene | Gene symbol | LogFc* | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression and Chromatin Regulation | Ubiquitin Like With PHD And Ring Finger Domains1 | UHRF1 | −1.24 | 0.00135 |

| DNA Methyltransferase 1 | DNMT1 | −1.36 | 0.000346 | |

| DNA Methyltransferase 3 Alpha | DNMT3A | −0.57 | 0.151911 | |

| DNA Methyltransferase 3 Beta | DNMT3B | −0.31 | 0.441236 | |

| Histone Deacetylase 1 | HDAC1 | −0.20 | 0.591253 | |

| Histone Deacetylase 4 | HDAC4 | −1.30 | 0.00086 | |

| Lysine Demethylase 1A | KDM1A | −0.34 | 0.363192 | |

| Lysine Demethylase 1B | KDM1B | −0.35 | 0.327579 | |

| Lysine Methyltransferase 2D | KMT2D | −0.71 | 0.061992 | |

| Lysine Demethylase 2B | KDM2B | −0.66 | 0.085492 | |

| Lysine Demethylase 3B | KDM3B | −0.58 | 0.123981 | |

| Lysine Demethylase 8 | KDM8 | −0.75 | 0.1994049 | |

| Lysine Demethylase 4C | KDM4C | −0.36 | 0.3233588 | |

| Lysine Methyltransferase 2A | KMT2A | −0.51 | 0.1761255 | |

| Lysine Methyltransferase 2B | KMT2B | −1.20 | 0.1436984 | |

| Lysine Methyltransferase 2C | KMT2C | −0.14 | 0.6599847 | |

| Lysine Methyltransferase 2E | KMT2E | −0.11 | 0.7236951 | |

| Forkhead Box O6 | FOXO6 | −0.70 | 0.2141747 |

*fold change treated vs untreated.

Interestingly, several tumor suppressor genes known to be epigenetically silenced in various tumors such as DDIT3, PPARGC1A and DLC1 were significantly up-regulated (Table 2), along with a significant increase in the expression of the pro-apoptotic genes BAD and CARD6 (Table 3) suggesting that DFMO-induced up-regulation of TSGs leading to apoptosis in Jurkat cells also involves epigenetic mechanisms in the same way like TQ.31

Table 2.

Upregulated Tumor Suppressor Genes in DFMO-Treated Jurkat Cells as Compared With Untreated Cells.

| Gene | Gene symbol | LogFc* | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor suppressor genes | CDKN2A Interacting Protein N-Terminal Like | DDIT3 | 3.26 | 7.57E-11 |

| PPARG Coactivator 1 Alpha | PPARGC1A | 2.64 | 0.000108 | |

| DLC1 Rho GTPase Activating Protein | DLC1 | 1.07 | 0.0345 | |

| Spalt Like Transcription Factor 4 | SALL4 | 4.44 | 0.607086 | |

| Suppression Of Tumorigenicity 7 | ST7 | 0.62 | 0.165587 | |

| Lysine Demethylase 3A | KDM3A | 0.77 | 0.0732 | |

| Lysine Demethylase 6A | KDM6A | 0.533 | 0.2491 | |

| Lysine Demethylase 7A | KDM7A | 0.90 | 0.0498 | |

| Tet Methylcytosine Dioxygenase 2 | TET2 | 0.34 | 0.4935 | |

| Cytochrome P450 Family 1 Subfamily B Member 1 | CYP1B1 | 0.79 | 0.5608 |

*fold change treated vs untreated.

Table 3.

Upregulated Pro-Apoptotic Genes in DFMO-Treated Jurkat Cells as Compared With Untreated Cells.

| Gene | Gene symbol | LogFc* | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pro-Apoptotic | BCL2 Associated agonist of Cell Death | BAD | 0.78 | 0.0674 |

| Caspase Recruitment Domain Family Member 6 | CARD6 | 2.810 | 0.02479 | |

| BCL2 Interacting Killer | BIK | 0.63 | 0.1427 |

*Fold change Treated vs Untreated.

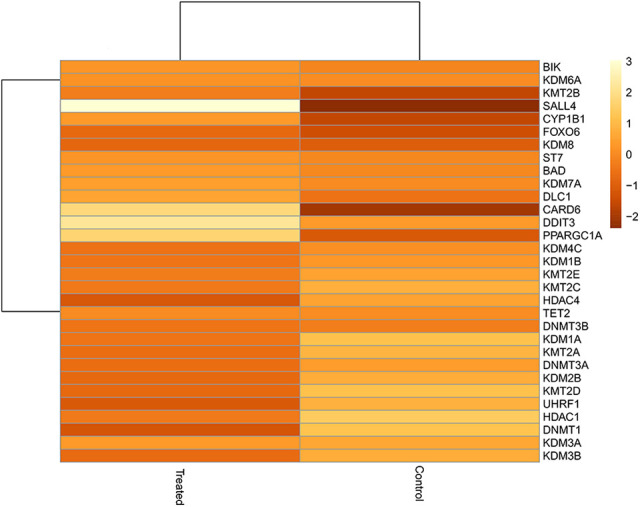

The heatmap presented in Figure 3 gives an overall overview of the expression of the modulated gene concerning both Log2-fold change (LogFC) in treated versus control cells.

Figure 3.

Heat map of the deregulated genes in treated versus control cells. The signature of the deregulated genes are represented in the intensity of color; with the alteration of LogFC (fold change) from -1 to +3 in DFMO-treated Jurkat cells as compared to the untreated cells.

Gene Expression Analysis of TQ and/or DFMO on Jurkat Cells

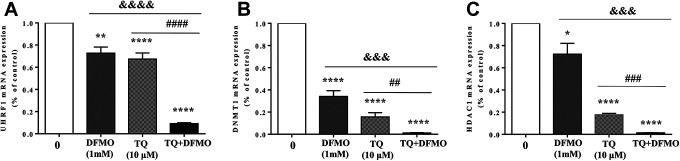

Our previous study has shown that TQ-induced apoptosis in Jurkat cells is associated with a down-regulation of the expression of a UHRF1/DNMT1/HDAC1 protein complex.23 Thus, we studied the combinatorial effect of DFMO and TQ on the interpretation of that complex using RT-qPCR (Figure 4). We found that the expression of all the 3 genes UHRF1, DNMT1 and HDAC1 were significantly decreased in Jurkat, treated with either DFMO or TQ compared to control (Figure 4). Interestingly, the combination of 2 drugs induced a significant reduction in the expression of target genes (P < 0.001) compared to either DFMO or TQ alone (Figure 4) suggesting a significant role of these epigenetic regulators in the synergistic pro-apoptotic effects of TQ and DFMO.

Figure 4.

Synergistic effect of TQ and DFMO on the expression of UHRF1, DNMT1 and HDAC1 mRNA levels in Jurkat cells. To evaluate the synergistic effect on the expression of UHRF1, DNMT1 and HDAC1 genes, cells were treated with either DFMO (1 mM) for 48 h or TQ (10 μM) or incubated with 1 mM of DFMO for 24 h before adding 10 μM of TQ for additional 24 h. The histograms show the quantification data of mRNA expressions of UHRF1 (A), DNMT1 (B) and HDAC1 (C), as assessed by real-time PCR. Results are means of 3 separate experiments performed in triplicate. Values are shown as means ± S.E.M. (n = 3); *, p < 0.05, ***, p < 0.001, ****, p < 0.0001, ##, p < 0.01, ###, p < 0.001, &&&, p < 0.001, ###, p < 0.001, &&&&, p < 0.0001 versus respective control.

UHRF1 Downregulation Mimics the Effect of TQ on Cell Viability in Jurkat Cells

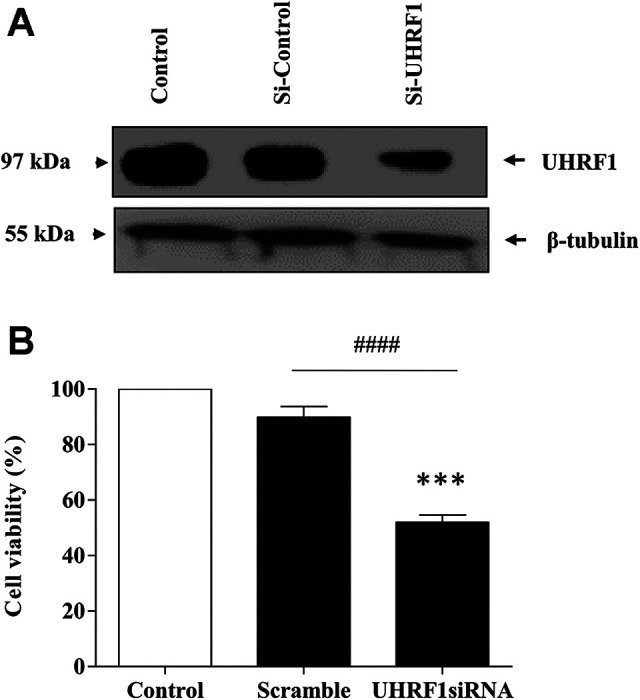

Several previous studies have shown that UHRF1 overexpression observed in many human cancers is a primary event in the initiation and the development of cancer through regulating several signaling pathways.32-37 To investigate whether UHRF1 can enhance cell proliferation in Jurkat cells, we examined the effect of UHRF1 knockdown on cell viability. The knockdown of UHRF1 in Jurkat cells (Figure 5A) led to a considerable decrease in the cell viability (Figure 5B) mimicking the effect of TQ on cell viability as shown in Figure 1B. This data indicates that UHRF1 promotes cell proliferation and could be a promising target for TQ in human acute T lymphoblastic leukemia.

Figure 5.

Effect of the depletion of UHRF1 cell viability. Jurkat cells were transfected with siRNA against UHRF1 for 72 h. (A): Western blot was then performed using an anti-UHRF1 antibody as described in materials and methods. (B): Cell viability was calculated using trypan blue as indicated in materials and methods. Data are shown as mean ± SE of 3 independent experiments (####P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001 versus respective control).

Discussion

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is considered as one of the most common childhood cancers with a high rate of mortality and morbidity accompanied by inferior prognosis.38,39 Nearly 25% of childhood ALL patients show a relapse within 5 years of treatment.40,41 Therefore, there is a persistent demand to find more efficient anti-leukemic drugs with low toxicity. An essential idea of worth consideration is that the combination of several drugs at small doses could minimize the undesirable effects of chemopreventive drugs by synergistic action.

Both the anticancer agents DFMO and TQ have been evaluated for synergistic effect with other anticancer drugs on many tumors,5,42,43 including leukemia.44,45 In the present study, we evaluated the synergistic effect of TQ and DFMO on Jurkat cells-an established cell line for acute T cell leukemia since the 1970s.46 The combination of DFMO and TQ dramatically decreased the expression of UHRF1, DNMT1 and HDAC1 genes in comparison to either DFMO or TQ alone. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first time that DFMO and TQ are used in combination for cancer therapy.

Real-time qPCR showed that the combination of DFMO and TQ significantly decreased the expression of UHRF1 gene and its partners DNMT1 and HDAC1 genes in comparison to either DFMO or TQ alone which could explain the high apoptosis rate of Jurkat, treated with both drugs in contrast to each one individually. This observation is in agreement with the previous studies which underlined the importance of UHRF1 downregulation in the induction of apoptosis in cancer cells in response to several natural products including TQ and epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG).23,29,31,47,48 Several in vitro and in vivo highlighted the potential of TQ as an anti-leukemic agent.49-51 Interestingly, TQ was shown to exhibit selective cytotoxicity toward cells 52-54 rendering this natural compound, a promising antitumor agent.

Several studies have demonstrated the contribution of the bone marrow stromal microenvironment in the survival of leukemia cells and the resistance to chemotherapy.55,56 This protective role was suggested to be attributed to the high expression levels of the cell surface receptor CXCR4 (chemokine receptor type 4) rendering the inhibition of this receptor as a potential target to overcome the leukemic resistance to chemotherapy.55 Interestingly, TQ was shown to decrease the expression of CXCR4 on multiple myeloma (MM) cells57 and breast cancer cells.58 Many studies have suggested that the altered phenotype of tumor-associated stromal cells could be primarily attributed to epigenetic mechanism including DNA methylation and histone modifications.59 In this context, hypermethylation-mediated epigenetic silencing of the tumor suppressor gene PTEN was observed in activated hepatic stellate cells60 and stromal fibroblasts.61 Interestingly, TQ was shown to increase the expression of PTEN gene in gastric cancer both in vitro and in vivo,62 triple-negative breast cancer63 and thyroid cancers64 supporting the idea that TQ could be efficient anti-leukemic drug through targeting the epigenetic code of tumor-associated stromal cells increasing the sensitivity to chemotherapy.

The present study also showed that UHRF1 knockdown led to cell proliferation inhibition indicating that UHRF1 has an oncogenic role in cell proliferation, which supports the idea that UHRF1 downregulation in response to natural products including TQ could be sufficient to trigger apoptosis. In our previous study, we have shown that TQ induces apoptosis by producing intracellular ROS and triggers apoptosis in Jurkat cells through the activation of the tumor suppressor gene p73 followed by a downregulation of UHRF1. These observations suggest that TQ induces intracellular ROS production leading to the deregulation of epigenetic regulators including UHRF1 and subsequent apoptosis in Jurkat cells.

Like several solid tumors, leukemia could be initiated by rare leukemic stem cells (LSCs) and the inefficient therapy of this type of cancers could be mainly attributed to the failure of elimination of LSCs. Thus, understanding how LSCs initiate leukemia will help develop new therapies which can enable us to selectively eliminate LSCs. Through targeting several stem cell regulatory pathways, TQ could be a promising candidate to eliminate leukemic stem/initiating cells and its combination with DMFO could enhance its activity. In line with our hypothesis, TQ was shown to induce apoptosis in both in vitro and in vivo studies and inhibit the tumor growth in pancreatic cancer stem cells.65 Moreover, the combination of TQ with the anticancer agent 5-fluorouracil has been shown to downregulate 2 stem cell regulatory signaling pathways WNT/ß-Catenin and PI3K/AKT and was able to eliminate CD133+ cancer stem cells population.66

It is intriguing to note that apart from many biosynthetic inhibitors available, DFMO has been the choice of study in vitro and in vivo 67,68 and preclinical trials.69,70 Many studies have been reported wherein DFMO was used alone or in combination with many anticancer agents5,42,43,71 for chemoprevention in a panel of different cell lines including leukemia.45 The present study showed that DFMO at low dose did not affect apoptosis. In contrast, a significant increase in apoptosis rate was found when DFMO was used in combination with TQ under similar conditions.

In conclusion, the present study shows that the combination of DFMO and TQ resulted in apoptosis of Jurkat cells through epigenetic mechanisms which could be promising to devise strategies for the treatment of human acute T lymphoblastic leukemia shortly.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR), at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, under grant no. (D-99-130-1438). The authors, therefore, gratefully acknowledge the technical and financial support from DSR.

ORCID iD: Syed Shoeb I. Razvi  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6590-2871

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6590-2871

References

- 1. Gerner EW, Meyskens FL. Polyamines and cancer: old molecules, new understanding. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(10):781–792. doi:10.1038/nrc1454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shantz LM, Levin VA. Regulation of ornithine decarboxylase during oncogenic transformation: mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Amino Acids. 2007;33(2):213–223. doi:10.1007/s00726-007-0531-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Elmets CA, Athar M. Targeting ornithine decarboxylase for the prevention of nonmelanoma skin cancer in humans. Cancer Prev Res. 2010;3(1):8–11. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xu H, Washington S, Verderame MF, Manni A. Role of non-receptor and receptor tyrosine kinases (TKs) in the antitumor action of alpha-difluoromethylornithine (DFMO) in breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;112(2):255–261. doi:10.1007/s10549-007-9866-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xie S, Liu G, Ma Y, et al. Synergistic antitumor effects of anthracenylmethyl homospermidine and alpha-difluoromethylornithine on promyelocytic leukemia HL60 cells. Toxicol In Vitro. 2008;22(2):352–358. doi:10.1016/j.tiv.2007.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arisan ED, Obakan P, Coker-Gurkan A, Calcabrini A, Agostinelli E, Unsal NP. CDK inhibitors induce mitochondria-mediated apoptosis through the activation of polyamine catabolic pathway in LNCaP, DU145 and PC3 prostate cancer cells. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20(2):180–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mohammed A, Janakiram NB, Madka V, et al. Eflornithine (DFMO) prevents progression of pancreatic cancer by modulating ornithine decarboxylase signaling. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2014;7(12):1198–1209. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-14-0176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Song H-P, Li R-L, Zhou C, Cai X, Huang H-Y. Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz stimulates intestinal epithelial cell migration through a polyamine dependent mechanism. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;159:23–35. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2014.10.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thomas T, MacKenzie SA, Gallo MA. Regulation of polyamine biosynthesis by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD). Toxicol Lett. 1990;53(3):315–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Luk GD, Civin CI, Weissman RM, Baylin SB. Ornithine decarboxylase: essential in proliferation but not differentiation of human promyelocytic leukemia cells. Science. 1982;216(4541):75–77. doi:10.1126/science.6950518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Luk GD, Goodwin G, Gazdar AF, Baylin SB. Growth-inhibitory effects of DL-alpha-difluoromethylornithine in the spectrum of human lung carcinoma cells in culture. Cancer Res. 1982;42(8):3070–3073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lao CD, Backoff P, Shotland LI, et al. Irreversible ototoxicity associated with difluoromethylornithine. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(7):1250–1252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Croghan MK, Aickin MG, Meyskens FL. Dose-related alpha-difluoromethylornithine ototoxicity. Am J Clin Oncol. 1991;14(4):331–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ajani JA, Ota DM, Grossie VBJ, et al. Evaluation of continuous-infusion alpha-difluoromethylornithine therapy for colorectal carcinoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1990;26(3):223–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang C, Delcros J-G, Biggerstaff J, Phanstiel O., IV Synthesis and biological evaluation of N1-(anthracen-9-ylmethyl)triamines as molecular recognition elements for the polyamine transporter. J Med Chem. 2003;46(13):2663–2671. doi:10.1021/jm030028w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang C, Delcros J, Biggerstaff J, Phanstiel O. Molecular requirements for targeting the polyamine transport system . synthesis and biological evaluation of polyamine—anthracene conjugates molecular requirements for targeting the polyamine transport system. J Med Chem. 2003;46(13):2672–2682. doi:10.1021/jm020598 g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Laukaitis CM, Gerner EW. DFMO: targeted risk reduction therapy for colorectal neoplasia. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25(4):495–506. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2011.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Meyskens FLJ, McLaren CE, Pelot D, et al. Difluoromethylornithine plus sulindac for the prevention of sporadic colorectal adenomas: a randomized placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2008;1(1):32–38. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Banerjee S, Padhye S, Azmi A, et al. Review on molecular and therapeutic potential of thymoquinone in cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2010;62(7):938–946. doi:10.1080/01635581.2010.509832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gholamnezhad Z, Havakhah S, Boskabady MH. Preclinical and clinical effects of Nigella sativa and its constituent, thymoquinone: a review. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;190:372–386. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2016.06.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ebrahimi SS, Oryan S, Izadpanah E, Hassanzadeh K. Thymoquinone exerts neuroprotective effect in animal model of Parkinson’s disease. Toxicol Lett. 2017;276:108–114. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2017.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yang Y, Bai T, Yao Y-L, et al. Upregulation of SIRT1-AMPK by thymoquinone in hepatic stellate cells ameliorates liver injury. Toxicol Lett. 2016;262:80–91. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2016.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Alhosin M, Abusnina A, Achour M, et al. Induction of apoptosis by thymoquinone in lymphoblastic leukemia Jurkat cells is mediated by a p73-dependent pathway which targets the epigenetic integrator UHRF1. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;79(9):1251–1260. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2009.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Alhosin M, Omran Z, Zamzami MA, et al. Signalling pathways in UHRF1-dependent regulation of tumor suppressor genes in cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2016;35(1):174 doi:10.1186/s13046-016-0453-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hsiao P-C, Liu M-C, Chen L-M, et al. Promoter methylation of p16 and EDNRB gene in leukemia patients in Taiwan. Chin J Physiol. 2008;51(1):27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bodoor K, Haddad Y, Alkhateeb A, et al. DNA hypermethylation of cell cycle (p15 and p16) and apoptotic (p14, p53, DAPK and TMS1) genes in peripheral blood of leukemia patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(1):75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lei X, Lv X, Liu M, et al. Thymoquinone inhibits growth and augments 5-fluorouracil-induced apoptosis in gastric cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;417(2):864–868. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.12.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dirican A, Atmaca H, Bozkurt E, Erten C, Karaca B, Uslu R. Novel combination of docetaxel and thymoquinone induces synergistic cytotoxicity and apoptosis in DU-145 human prostate cancer cells by modulating PI3K–AKT pathway. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17(2):145–151. doi:10.1007/s12094-014-1206-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Razvi SS, Choudhry H, Hasan MN, et al. Identification of deregulated signaling pathways in Jurkat cells in response to a novel acylspermidine analogue-N(4)-erucoyl spermidine. Epigenetics insights. 2018;11:2516865718814543 doi:10.1177/2516865718814543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Achour M, Jacq X, Rondé P, et al. The interaction of the SRA domain of ICBP90 with a novel domain of DNMT1 is involved in the regulation of VEGF gene expression. Oncogene. 2008;27(15):2187–2197. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1210855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Qadi SA, Hassan MA, Sheikh RA, et al. Thymoquinone-induced reactivation of tumor suppressor genes in cancer cells involves epigenetic mechanisms. Epigenetics insights. 2019;12:2516865719839011 doi:10.1177/2516865719839011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ashraf W, Ibrahim A, Alhosin M, et al. The epigenetic integrator UHRF1: on the road to become a universal biomarker for cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(31):51946–51962. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.17393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Choudhry H, Zamzami MA, Omran Z, et al. Targeting microRNA/UHRF1 pathways as a novel strategy for cancer therapy. Oncol Lett. 2018;15(1):3–10. doi:10.3892/ol.2017.7290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hasan MN, Razvi SS, Choudhry H, et al. Gene ontology and expression studies of strigolactone analogues on a hepatocellular carcinoma cell line. Anal Cell Pathol (Amst). 2019;2019:1598182 doi:10.1155/2019/1598182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Foster BM, Stolz P, Mulholland CB, et al. Critical role of the UBL domain in stimulating the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of UHRF1 toward chromatin. Mol Cell. 2018;72(4):739–752. e9 doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2018.09.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Xue B, Zhao J, Feng P, Xing J, Wu H, Li Y. Epigenetic mechanism and target therapy of UHRF1 protein complex in malignancies. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:549–559. doi:10.2147/OTT.S192234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vaughan RM, Rothbart SB, Dickson BM. The finger loop of the SRA domain in the E3 ligase UHRF1 is a regulator of ubiquitin targeting and is required for the maintenance of DNA methylation. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(43):15724–15732. doi:10.1074/jbc.RA119.010160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cooper SL, Brown PA. Treatment of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2015;62(1):61–73. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2014.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pui C-H, Carroll WL, Meshinchi S, Arceci RJ. Biology, risk stratification, and therapy of pediatric acute leukemias: an update. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(5):551–565. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.30.7405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bhojwani D, Pui C-H. Relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(6):e205–217. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70580-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ma H, Sun H, Sun X. Survival improvement by decade of patients aged 0-14 years with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a SEER analysis. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4227 doi:10.1038/srep04227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wattenberg LW, Wiedmann TS, Estensen RD. Chemoprevention of cancer of the upper respiratory tract of the Syrian golden hamster by aerosol administration of difluoromethylornithine and 5-fluorouracil. Cancer Res. 2004;64(7):2347–2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Burns MR, Graminski GF, Weeks RS, Chen Y, O’Brien TG. Lipophilic lysine-spermine conjugates are potent polyamine transport inhibitors for use in combination with a polyamine biosynthesis inhibitor. J Med Chem. 2009;52(7):1983–1993. doi:10.1021/jm801580w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mostofa AGM, Hossain MK, Basak D, Bin Sayeed MS. Thymoquinone as a potential adjuvant therapy for cancer treatment: evidence from preclinical studies. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:295 doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Alexiou GA, Lianos GD, Ragos V, Galani V, Kyritsis AP. Difluoromethylornithine in cancer: new advances. Future Oncol. 2017;13(9):809–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schneider U, Schwenk HU, Bornkamm G. Characterization of EBV-genome negative “null” and “T” cell lines derived from children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and leukemic transformed non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Int J cancer. 1977;19(5):621–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Achour M, Mousli M, Alhosin M, et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate up-regulates tumor suppressor gene expression via a reactive oxygen species-dependent down-regulation of UHRF1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;430(1):208–212. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.11.087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ibrahim A, Alhosin M, Papin C, et al. Thymoquinone challenges UHRF1 to commit auto-ubiquitination: a key event for apoptosis induction in cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2018;9(47):28599–28611. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.25583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nichols WW. Continuous cardiac output derived from the aortic pressure waveform: a review of current methods. Biomed Eng (NY). 1973;8(9):376–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pang J, Shen N, Yan F, et al. Thymoquinone exerts potent growth-suppressive activity on leukemia through DNA hypermethylation reversal in leukemia cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8(21):34453–34467. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.16431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Alhosin M. Thymoquinone is a novel potential inhibitor of SIRT1 in cancers with p53 mutation: role in the reactivation of tumor suppressor p73. World Acad Sci J. 2020;4(23):1–8. doi:10.3892/wasj.2020.49 [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gali-Muhtasib HU, Abou Kheir WG, Kheir LA, Darwiche N, Crooks PA. Molecular pathway for thymoquinone-induced cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in neoplastic keratinocytes. Anticancer Drugs. 2004;15(4):389–399. doi:10.1097/00001813-200404000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ivankovic S, Stojkovic R, Jukic M, Milos M, Milos M, Jurin M. The antitumor activity of thymoquinone and thymohydroquinone in vitro and in vivo. Exp Oncol. 2006;28(3):220–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Alhosin M, Ibrahim A, Boukhari A, et al. Anti-neoplastic agent thymoquinone induces degradation of α and β tubulin proteins in human cancer cells without affecting their level in normal human fibroblasts. Invest New Drugs. 2012;30(5):1813–1819. doi:10.1007/s10637-011-9734 -1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sison EAR, Brown P. The bone marrow microenvironment and leukemia: biology and therapeutic targeting. Expert Rev Hematol. 2011;4(3):271–283. doi:10.1586/ehm.11.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Houshmand M, Blanco TM, Circosta P, et al. Bone marrow microenvironment: the guardian of leukemia stem cells. World J Stem Cells. 2019;11(8):476–490. doi:10.4252/wjsc.v11.i8.476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Badr G, Lefevre EA, Mohany M. Thymoquinone inhibits the CXCL12-induced chemotaxis of multiple myeloma cells and increases their susceptibility to Fas-mediated apoptosis. PLoS One. 2011;6(9): e23741 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Shanmugam MK, Ahn KS, Hsu A, et al. Thymoquinone inhibits bone metastasis of breast cancer cells through abrogation of the CXCR4 signaling axis. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1294 doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.01294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Marks DL, Olson R Lo, Fernandez-Zapico ME. Epigenetic control of the tumor microenvironment. Epigenomics. 2016;8(12):1671–1687. doi:10.2217/epi-2016-0110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bian E-B, Huang C, Ma T-T, et al. DNMT1-mediated PTEN hypermethylation confers hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrogenesis in rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012;264(1):13–22. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2012.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Trimboli AJ, Cantemir-Stone CZ, Li F, et al. Pten in stromal fibroblasts suppresses mammary epithelial tumours. Nature. 2009;461(7267):1084–1091. doi:10.1038/nature08486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ma J, Hu X, Li J, et al. Enhancing conventional chemotherapy drug cisplatin-induced anti-tumor effects on human gastric cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo by thymoquinone targeting PTEN gene. Oncotarget. 2017;8(49):85926–85939. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.20721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Barkat MA, Harshita, Ahmad J, Khan MA, Beg S, Ahmad FJ. Insights into the targeting potential of thymoquinone for therapeutic intervention against triple-negative breast cancer. Curr Drug Targets. 2018;19(1):70–80. doi:10.2174/1389450118666170612095959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ozturk SA, Alp E, Yar Saglam AS, Konac E, Menevse ES. The effects of thymoquinone and genistein treatment on telomerase activity, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and survival in thyroid cancer cell lines. J Cancer Res Ther. 2018;14(2):328–334. doi:10.4103/0973-1482.202886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Mu G-G, Zhang L-L, Li H-Y, Liao Y, Yu H-G. Thymoquinone pretreatment overcomes the insensitivity and potentiates the antitumor effect of gemcitabine through abrogation of Notch1, PI3K/Akt/mTOR regulated signaling pathways in pancreatic cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(4):1067–1080. doi:10.1007/s10620-014-3394-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ndreshkjana B, Çapci A, Klein V, et al. Combination of 5-fluorouracil and thymoquinone targets stem cell gene signature in colorectal cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10(6):379 doi:10.1038/s41419-019-1611-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Reddy BS, Nayini J, Tokumo K, Rigotty J, Zang E, Kelloff G. Chemoprevention of colon carcinogenesis by concurrent administration of piroxicam, a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug with D, L-alpha-difluoromethylornithine, an ornithine decarboxylase inhibitor, in diet. Cancer Res. 1990;50(9):2562–2568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Li H, Schut HA, Conran P, et al. Prevention by aspirin and its combination with alpha-difluoromethylornithine of azoxymethane-induced tumors, aberrant crypt foci and prostaglandin E2 levels in rat colon. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20(3):425–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Lynch PM, Burke CA, Phillips R, et al. An international randomised trial of celecoxib versus celecoxib plus difluoromethylornithine in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut. 2016;65(2):286–295. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Simoneau AR, Gerner EW, Nagle R, et al. The effect of difluoromethylornithine on decreasing prostate size and polyamines in men: results of a year-long phase IIb randomized placebo-controlled chemoprevention trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(2):292–299. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Weeks RS, Vanderwerf SM, Carlson CL, et al. Novel lysine-spermine conjugate inhibits polyamine transport and inhibits cell growth when given with DFMO. Exp Cell Res. 2000;261(1):293–302. doi:10.1006/excr.2000.5033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]