Abstract

Backgrounds and Aims

A major challenge when supporting the development of intercropping systems remains the design of efficient species mixtures. The ecological processes that sustain overyielding of legume-based mixtures compared to pure crops are well known, but their links to plant traits remain to be unravelled. A common assumption is that enhancing trait divergence among species for resource acquisition when assembling plant mixtures should increase species complementarity and improve community performance.

Methods

The Virtual Grassland model was used to assess how divergence in trait values between species on four physiological functions (namely light and mineral N acquisition, temporal development, and C–N use efficiency) affected overyielding and mixture stability in legume-based binary mixtures. A first step allowed us to identify the model parameters that were most important to interspecies competition. A second step involved testing the impact of convergent and divergent parameter (or trait) values between species on virtual mixture performance.

Results

Maximal overyielding was achieved in cases where trait values were divergent for the physiological functions controlling N acquisition and temporal development but convergent for light interception. It was also found that trait divergence should not affect competitive abilities of legume and non-legumes at random. Indeed, random trait combinations frequently led to reduced mixture yields when compared to a perfectly convergent neutral model. Combinations with the highest overyielding also tended to be associated with mixture instability and decreasing legume biomass proportion. Achieving both high overyielding and mixture stability was only found to be possible under low or moderate N levels, using combinations of traits adapted to each environment.

Conclusions

No simple assembly rule based on trait divergence could be confirmed. Plant models able to infer plant–plant interactions can be helpful for the identification of major interaction traits and the definition of ideotypes adapted to a targeted intercropping system.

Keywords: Intercropping, forage mixtures, individual-based model, competition, facilitation, species abundance, overyielding, ideotypes, assembly rules

INTRODUCTION

The use of plant diversity in agriculture is a pillar of agroecology and a major lever to promote resilient and sustainable production systems (Li et al., 2014; Altieri et al., 2015; Gaba et al., 2015). At the field scale, plant diversity is increased by intercropping, i.e. growing at least two crop species together for a significant portion of their growth cycle (Vandermeer, 1989). The advantages of crop mixtures over their corresponding sole crops have long been highlighted in the context of low-input agriculture (for reviews, see Lithourgidis et al., 2011; Bedoussac et al., 2015). Regarding forage production, multi-species grasslands are typically promoted for ruminants in Europe and rely heavily on the ecological and nutritional complementarities between perennial grasses and legumes (Louarn et al., 2010; Lüscher et al., 2014). Similarly, for grain crops, mixing cereals and grain legumes offers potential benefits in terms of production (e.g. grain yield and quality), improvements to soil biogeochemistry, pest control and reducing greenhouse gas emissions (Jeuffroy et al., 2015; Raseduzzaman and Jensen, 2017; Duchene et al., 2017).

A major challenge in terms of supporting the development of such intercropping systems remains the design of efficient species or cultivar mixtures (Wezel et al., 2014; Brooker et al., 2015; Maamouri et al., 2015). Indeed, the objective with these systems is to create cultivated plant communities where natural regulation, plant–plant interactions and plant complementarities in terms of resource requirements (in both space and time) will produce an overall positive effect on agroecosystem functioning and production. This is often achieved in legume-based mixtures as a result of the niche separation for nitrogen (N) offered by legumes, which can fix atmospheric N and improve N cycling in arable soils (Corre-Hellou et al., 2006; Nyfeler et al., 2011). A common measure of overall mixture performance in these situations is the difference between the total yield of the mixture and that of the average of monocultures (i.e. overyielding, OY). When positive, this metric denotes a better use of environmental resources by the mixture. However, if the combination of cultivar, climate and management is not suitable, competition between intercropped species can prevail so that the total yield will be less than the corresponding sole crops (i.e. negative OY; Baxevanos et al., 2017).

In the same way as for single crops, modelling can provide general guidelines to promote favourable designs and management practices for intercropping systems (Malézieux et al., 2009; Evers et al., 2018; Gaudio et al., 2019). In particular, mechanistic models can help to deepen our understanding of the processes at work in cultivated plant communities and to generalize based on the empirical knowledge gathered during numerous separate experiments (Brooker et al., 2015). More importantly, modelling also appears to be the only approach that can address the combinatorics lock-in generated by the analysis of ‘complex mixtures’ in various scientific domains (e.g. chemical interactions in the environmental sciences; Kortenkamp and Altenburger, 1999; Delfosse et al., 2015). For example, a simple binary mixture with six cultivars available for each crop gives rise to 32 (25) combinations when the cultivars are considered independently from each another. Just allowing the possibility of mixing two cultivars of each species (as is common practice with forage and cereal crops; Barot et al., 2017) raises the number to 216 theoretical combinations, which is obviously beyond the reach of conventional empirical approaches. Functional–structural plant modelling (FSPM) therefore has a role to play in delivering efficient screening methods of a plant’s competitive ability that can target experimental efforts on the most promising plant combinations and valorize the computational power offered by numerical models. This approach can take advantage of its ability to simulate the functioning of a mixture and interactions between mixed species based on the integration of local exchanges of plant parts with their abiotic environment (i.e. light, temperature and soil resources), independently of the identity of neighbouring plants. No competitive effects are forced in such models and competition-facilitation effects are an outcome of model functioning (i.e. an emergent property) that is directly derived from the independent plant parameters (or traits) gathered in the plant community (Louarn and Faverjon, 2018; Evers et al., 2018).

With the aim of bridging plant traits with the quantitative performance of grasslands, the ‘Virtual Grassland’ model (VGL) was developed to integrate and analyse the functioning of multi-species forage mixtures in response to light, water and N availability (Louarn et al., 2014). It was recently assessed for legume-based mixtures (Faverjon et al., 2019a), and displayed a good capacity to predict forage yield, N fixation by legumes and changes to species proportions over time. As it successfully integrated the local responses of plants both above and below ground, VGL was able to upscale plant–plant interactions at the community level under contrasting conditions of competition for light and N. This type of model could thus be a complementary tool to the existing empirical rules applied to design grassland mixtures and make the whole process of assembling species and cultivars more efficient. The current assembly rules applied to grassland mixtures are mostly derived from the study of natural communities (i.e. from the ecological processes selecting for or against species and determining local community composition; Drake, 1990; Götzenberger et al., 2012) and are still perfectible. They are driven by general ecological principles that seek to maximize divergence of trait values between species (and supposedly niche complementarity) in order to promote a positive OY (Mosimann et al., 2012; Litrico and Violle, 2015; Goutiers et al., 2016).

Taking Faverjon et al. (2019a) as the starting point, the objective of the present paper was to use a modelling approach to investigate the determinants of overyielding in legume-based forage mixtures. The first aim was to identify the principal plant parameters (i.e. plant traits) involved in carbon (C) and N economy that control total above-ground biomass production and OY in such binary mixtures (which major traits, and do they differ from those in sole crops?). The second aim was to determine whether ‘trait divergence’ for resource acquisition (C and N) was indeed a relevant proxy to maximize species complementarity and overyielding (which trait variations and which combinations between legume and non-legume species?). To achieve this, the VGL model was used to simulate virtual competition experiments in theoretical binary mixtures with and without legumes, under three N management scenarios. The model considered plant competition for light and mineral N, and the facilitation effects caused by legumes through N released into the soil, all previously identified as being critical processes that affect the dynamics of legume-based mixtures (Thornley, 2001). Model outputs relative to forage production, OY and relative species abundance were analysed with respect to the different scenarios and parameter combinations tested.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Overview of the model

The legume population model of VGL was used in this study, for which a detailed description can be found in Louarn and Faverjon (2018; source code freely available at https://sourcesup.renater.fr/projects/l-egume/). Only its principal features are described below. The model deals with 3-D shoot and root morphogenesis for contrasting plant morphotypes, as well as C, water and N exchanges with the environment for each individual in a plant community. It is based on the L-system formalism (Prusinkiewicz and Lindenmayer, 1990) and coupled within VGL to two environmental models dealing with radiation transfer and light interception above ground (Sinoquet et al., 2001) and soil water and mineral N balances below ground (Louarn et al., 2016).

The plant model uses a daily time step to compute the potential morphogenesis of shoots and roots as a result of the functioning of plant meristems and growing tissues. Potential morphogenetic frameworks, adapted from Faverjon et al. (2017) for shoots and Pagès et al. (2014) for roots, are used in the L-system. Total plant dry matter production is determined from light interception by shoots using a radiation use efficiency approach, which in turn defines the water and N required to sustain maximum plant growth. Biomass allocation between shoots and roots is assumed to follow an allometric relationship in the absence of trophic limitations. Relative C demands to sustain maximum organ expansion are then assumed to drive the partitioning of dry matter between shoot leaves and stems.

Two feedback loops are implemented to account for plant plasticity and the regulation of plant growth and morphogenesis by the environment. On the one hand, light quality distribution is deemed to trigger local photo-morphogenetic responses, which down-regulate phytomer production by shoot axes (Baldissera et al., 2014) and modulate organ expansion (Gautier et al., 2000). The trophic effects of light competition are also considered through the application of minimum C costs to achieve maximum tissue expansion in roots (Pagès et al., 2014). On the other hand, the soil resources available to plant roots are compared with water and N requirements in order to scale actual plant growth. Two ratios accounting for water availability (FTSW) and the satisfaction of N demand (NNI) are calculated from plant uptake in the soil. These ratios define two levels of stress that are applied both systemically (whole plant level) and independently (multiplicative effects) in order to regulate plant growth. In the event of insufficient mineral N to meet plant demands, biological N fixation is simulated for legume species. N fixation comes at a C cost associated with nodule formation and turnover (Voisin and Gastal, 2015). Shoot organs and roots are subject to tissue senescence. Dead plant parts enter fresh pools of C and N residues released into the soil that follow a kinetic of mineralization which depends on their C/N composition and on soil conditions (Brisson et al., 2008). The model is thus able to take into account both negative (i.e. competition for light, water and mineral N) and positive (N facilitation) plant–plant interactions. A total of 43 equations with about 120 parameters are defined in the plant model. Only the 28 principal parameters involved in plant morphogenesis and C and N use are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of plant parameters used for the sensitivity analysis and their respective ranges of variation. Light grey, grey, dark grey and white backgrounds indicate parameters associated with shoot morphogenesis, root morphogenesis, C and N use, and N stress responses, respectively.

| Parameter | Description | Unit | Range (min/max) | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Del50 In | Delay before the onset of internode growth within a phytomer | phyllochron | 0/3 | 1, 4 |

| Del50 L | Delay before the onset of leaf growth within a phytomer | phyllochron | 0/1 | 1 |

| Elv L | Average elevation angle of the leaves | ° | 20/70 | 1 |

| L max In | Maximum internode length | cm | 2.5/6 | 1 |

| L max L | Maximum leaf length | cm | 2/5.5 | 1, 4, 5 |

| nsh max | Ceiling number of primary axes | – | 4/50 | 1, 4, 5 |

| Phyllo 1 | Phyllochron for the primary axes | °Cd | 20/60 | 1, 4, 5 |

| q | Parameter controlling optimal temperature | – | 1.5/3.2 | 1, 6 |

| SPAN L | Leaf lifespan for isolated plants | Phyllochron | 10/30 | 1 |

| Tilr | Tillering rate | Per phyllochron | 0.2/1.2 | 1, 4, 5 |

| Alloc FR | Partitioning coefficient between fine roots and taproot | g g–1 | 0.10/0.75 | 2, 4 |

| D min | Minimum root apex diameter | cm | 0.01/0.03 | 2, 3 |

| D max | Maximum root apex diameter | cm | 0.04/0.25 | 2, 3 |

| Dldm | Average ratio between lateral and parent root diameters | – | 0.1/0.45 | 2, 3 |

| Elmax R | Elongation rate of roots at the maximal apex diameter | cm °Cd–1 | 0.07/0.25 | 2, 3 |

| IBD | Average inter-branch distance | cm | 0.20/0.40 | 2, 3 |

| GDs | Root growth duration parameter | °Cd mm−2 mg−1 | 1000/2500 | 2, 3 |

| LDs | Root lifespan parameter | °Cd mm−2 mg−1 | 30 000/100 000 | 2, 3 |

| RTD | Root tissue density | g m−3 | 0.03/0.12 | 2, 3 |

| FIX max | Maximum plant fixation rate | g N kg–1− | 0/36 | 7 |

| NODcost | Relative reduction in RUE for a 100 % fixing plant | – | 0.05/0.35 | 7, 8 |

| RUE | Whole plant radiation use efficiency by non-fixing plants | g MJ PAR−1 | 1.8/3 | 8, 9 |

| VMAX 1 | Maximum rates of absorption achieved by the HATS | µmol cm−1 °Cj−1 | 0.0018/0.018 | 10 |

| VMAX 2 | Maximum rates of absorption achieved by the LATS | µmol cm−1 °Cj−1 | 0.05/0.5 | 10 |

| KMAX 2 | Michaelis affinity constant for the LATS | µmol cm−1 | 25 000/100 000 | 10 |

| NNI50 growth | NNI at which a 50 % reduction in organ growth occurs | – | 0.4/0.6 | 10, 11 |

| NNI50 dev | NNI at which a 50 % reduction in axis development occurs | – | 0.4/0.6 | 10, 11 |

| NNI50 photo | NNI at which a 50 % reduction in photosynthesis occurs | – | 0.3/0.5 | 10, 11 |

| ZETA tresh | ζ threshold inducing a cessation of axis development | – | 0.25/0.45 | 12 |

1: Faverjon et al. (2017); 2: Pagès (2016); 3: Faverjon et al. (2019b); 4: Migault (2015); 5: Nelson (2000); 6: Zaka et al. (2017); 7: Voisin et al., (2015); 8: Gosse et al. (1988); 9: Bélanger et al. (1994); 10: Brisson et al. (2008); 11: Gastal et al. (2015); 12: Baldissera et al. (2014).

Sensitivity analysis

A first step in determining the major traits involved in inter-plant competition was to perform a sensitivity analysis of the plant model in binary species mixtures. The term ‘species mixture’ will be used to refer to the binary mixture between two virtual species defined by two different sets of parameter values. For the sensitivity analysis, a reference plant morphotype was defined as a target competitor. The G- morphotype (i.e. erect crown-former, slightly modified from the alfalfa calibration, Louarn and Faverjon, 2018) was chosen, as it seemed a good candidate to represent productive grassland species under low N environments that are relevant to legume-based grasslands. A simple approach involving the change of one-parameter-at-a-time (OAT) was used to define a range of virtual companion species and quantify the effects of parameter values in the companion species on model outputs (Saltelli et al., 2000). An important step therefore consisted of determining the nominal values and ranges of model parameters for the companion species. The nominal values were taken as being equal to the G-morphotype, thus defining a neutral situation of competition where mixed species were identical in terms of their parameters and equal regarding their prospects for growth, reproduction and death (Chave, 2004). Then, for 28 of the parameters involved in C–N acquisition and use, we synthesized several publications to find an adequate range of variation for each parameter covering an interspecific range of values among herbaceous grassland species (Table 1). Five step values were regularly sampled within this range of variation in order to run the simulations. The sensitivity of model outputs was then measured by monitoring changes to the targeted output values using linear regression with parameter variation. During this screening phase, no interactions between the parameters were considered and only the main effect of each parameter on the variance of model outputs was computed. Two main outputs were targeted during this phase: the total annual production of the community (Ytot) and the relative yield of the companion species in a mixture sown at 50/50 % (p50s). To compare the sensitivity of binary mixtures vs. pure stands, the same sensitivity analysis was performed on a monospecific stand of a single species having the characteristics of the companion species tested.

During this exercise, the simulations were performed for dense plant stands (400 plants m−2) during the first year of production after stand establishment. The plot location was typical of Western European temperate grasslands (Lusignan, 46.26°N, 0.11°E) and we considered 30-year average weather data (1986–2016) as the meteorological inputs for the model. The edaphic conditions used as inputs corresponded to a 1.5-m-deep soil with 1.1 g organic N kg–1 in the upper soil layer. Under low to moderate N fertilization, this soil usually produces N-limiting growing conditions for non-fixing grassland species, even when grown in a mixture (Louarn et al., 2015). Here, the management method applied allowed for moderate N fertilization with 30 kg N ha−1 during each regrowth (i.e. 120 kg N ha−1 year−1) as well as an irrigation schedule matching potential evapotranspiration and crop water requirements. Four harvests were performed during the year according to a fixed schedule (on days of the year numbers 189, 230, 283 and 335). The simulations were replicated five times for each trait combination and sowing proportion in order to integrate the effect of random processes in the model functioning (e.g. stem and leaf angles). The soil and sky conditions were taken as in Louarn and Faverjon (2018).

Virtual experiments

A second step when analysing the role of major plant traits in the performance of grassland mixtures was to build a virtual experiment to test binary mixtures that varied in terms of their trait value composition. This was performed under two possible scenarios: the first dealing with binary mixtures without legumes and the second systematically combining a legume species with a non-legume species. The same plant model was used both for legumes (i.e. FIXmax set at the nominal value of 24 g N kg–1) and non-legumes (i.e. N fixation disabled; FIXmax parameter set at 0 g N kg–1).

To test the relevance of assembly rules based on maximal trait divergence, the role of major plant traits controlling four physiological functions (i.e. light acquisition, mineral N acquisition, growth kinetics and radiation use efficiency) involved in the niche separation of species was examined. Based on the results of the sensitivity analysis (see Results), four model parameters associated with these four physiological functions were selected from the 28 parameters previously tested. They corresponded to the parameters which displayed the strongest effects on model outputs in mixtures for each physiological function. The virtual experiment then consisted of testing a large range of the possible binary mixtures involving combinations of parameter value differences for these four traits under a factorial design with three levels allowed for each trait (sampled in the range between the highest differential in favour of the legume and half of the highest differential in favour of the non-legume; Supplementary Data Fig. S1). This defined a total of 57 possible mixtures, with one of them corresponding to a null model of competition. This latter situation represented the case of a perfect convergence of trait values between the mixed species (i.e. difference of parameter values equal to zero), for which the virtual species differed only by their ability to fix atmospheric N.

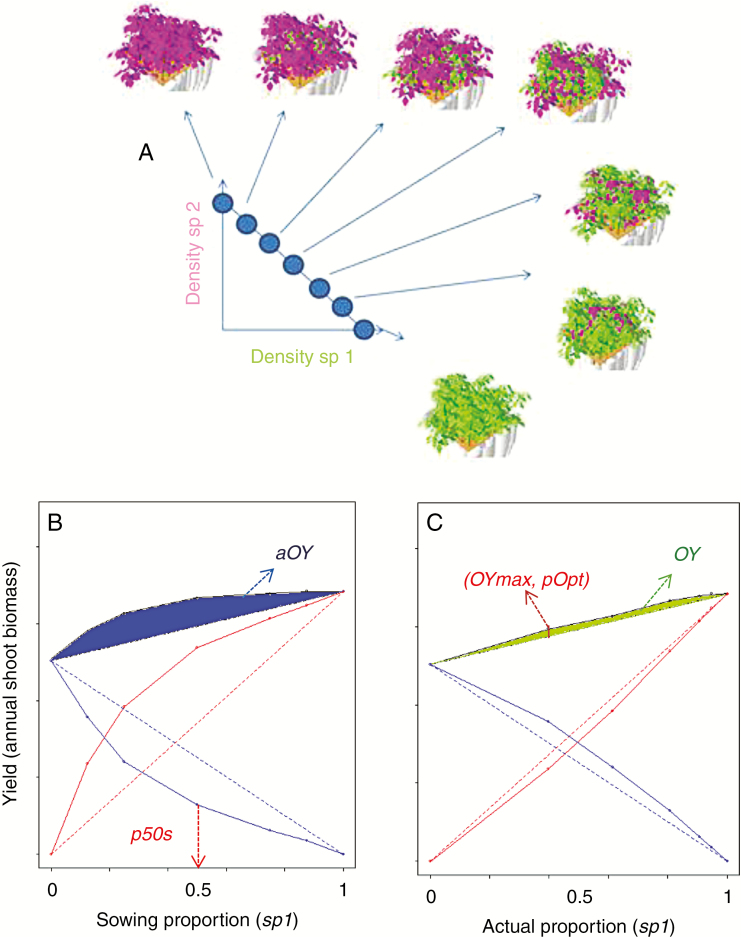

As the outcome of competition experiments is usually affected by intra- and inter-specific competition, and is thus sensitive to both absolute and relative plant densities (Hamilton, 1994), each binary mixture was analysed using a whole set of simulations at high density considering different proportions of species according to a classic replacement design (de Wit, 1960). Seven relative densities were tested for each species (i.e. 100, 87.5, 75, 50, 25, 12.5 and 0 %; Fig. 1A). This allowed us to properly disentangle the effects of plant traits, initial species proportions and actual species proportions on the overall annual production of the community.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of de Wit’s replacement design simulated for each virtual binary mixture (A) and of the assessment criteria derived from the yield relationships obtained with sowing proportions (B) and actual proportions in the mixture (C). aOY: average apparent overyielding; OY: average overyielding; p50s: actual proportion achieved with 50/50 sowing; OYmax: maximum overyielding; pOpt: proportion at maximum overyielding. Virtual species 1 (in blue) and species 2 (red) are plotted in different colours in B and C.

During this virtual experiment, the simulations were performed using the same location, climate, soil and management data as in the sensitivity analysis described above. However, to test the dependency of the conclusions on soil N fertility, three different mineral N application scenarios were tested, corresponding to zero (0N), moderate (120N, 120 kg N ha−1 year−1) and high (400N, 400 kg N ha−1 year−1) fertilization rates. Approximately 12 000 independent simulations were run for this study.

Assessment of mixture performance

The simulations of de Wit’s replacement designs made it possible to compute different indices characterizing resource acquisition and overyielding for each of the trait combinations tested. Plotting partial yields of the mixed species (Ypi,j; Ypj,i) and total annual production (Ytot = Ypi,j + Ypj,i) against species proportions at sowing (psow,i) made it possible to compute an apparent overyielding (aOY) for each species proportion using the total annual yields of the two pure species as a reference (Yi,i, Yj,j):

| (1) |

An average value for this apparent overyielding () could be determined over the whole range of sowing proportions at a given N level (Fig. 1B) and was used as a global metric of mixture performance under these conditions. In addition, the stability of the mixture was assessed by determining the shift of species proportions that occurred after 1 year at a 50/50 sowing (p50s = Ypi,j/Ytot). This index is related to the relative crowding coefficient proposed by de Wit (1960), but it does not scale with the relative yields of pure species (Harper, 1977). Thus a 0.5 value for p50s indicated that the proportions did not change and could define a reference objective independently of pure species yields.

In addition, actual overyielding (OY) was determined for each mixture by plotting partial yields of the mixed species and total annual production against the species biomass proportions actually achieved in the mixture at harvest (pi):

| (2) |

Maximal (OYmax) and average overyielding () values could also be determined (Fig. 1C). Finally the species proportion at which maximal overyielding was achieved (pOpt) was also taken as a supplementary criterion of mixture performance. For a stable mixture (p50s close to 0.5), pOpt could indicate the sowing proportion to be targeted in order to achieve maximum overyielding.

Similar indices were also computed regarding N uptake by the plants (including mineral N and atmospheric fixation ) and N overyielding with the different mixtures ().

RESULTS

Comparison of sensitive parameters in pure and mixed stands

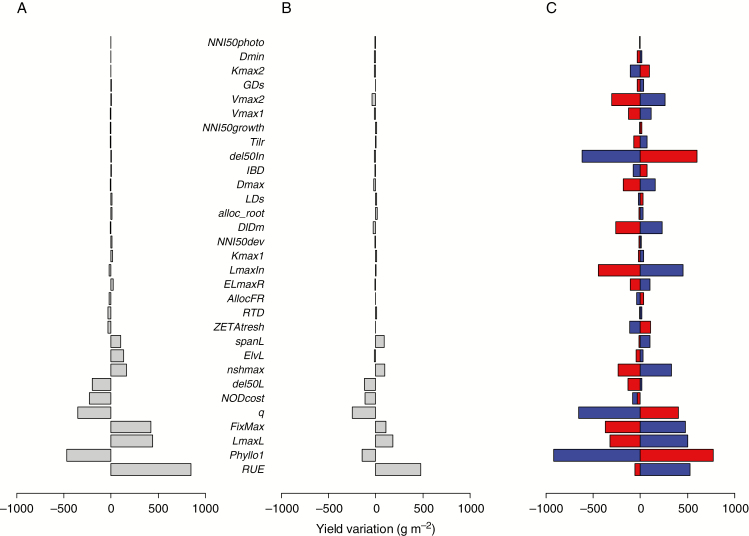

Figure 2 presents the impact of single parameter variations on the total annual yield predicted by the model in pure and mixed stands. The parameters that most affected yield in pure stands (Fig. 2A) were related to the kinetics of canopy development (phyllo1, LmaxL, q) and to radiation use efficiency (RUE, FixMax, NODcost). Despite the low N availability, a greater sensitivity of yield to the parameters involved in shoot morphogenesis could be noted when compared to the root morphogenesis, root functioning and N stress response parameters. The total annual yield of the community in mixed stands displayed a pattern of sensitive parameters remarkably similar to that of the pure stands (Fig. 2B). The same four parameters had the strongest influence (i.e. RUE, q, LmaxL and phyllo1). However, for all the parameters tested, the sensitivity of total annual yield to parameter variations appeared to be lower in mixed than in pure stands (y = 0.48x, r2 = 0.89).

Fig. 2.

Main effects of individual plant parameters on variations in total annual yield in a monospecific stand (A), on total annual yield in a 50/50 binary mixture (B) and on partial yields of the associated species (C). The parameter bars are ranked according to their influence on yield in a monospecific stand. In a mixture, changes to parameter values affected species 1 (in blue), whereas species 2 (red) retained identical parameter values. The sign and magnitude of yield variations result from an increase in parameter values as indicated by the range in Table 1.

Remarkably, the partial yields of the two companion species in a mixture showed a much broader range of variation than total annual yield in response to the imposed changes in model inputs (Fig. 2C). This indicated (1) that the mixture composition was much more sensitive to trait values than community productivity, and (2) that compensatory effects occurred between the associated species (as indicated by the opposite signs of their yield variations), thus explaining the buffered effect on biomass production at the community level. The parameters that most affected community productivity were also associated with strong effects on the partial yields of species (i.e. RUE, q, LmaxL, phyllo1 and FixMax). However, several other parameters also displayed marked effects on partial yields and mixture balance without effects on community productivity. For example, this was the case for parameters involved in stem elongation (LmaxIn, Del50In), root growth (DlDm, Dmax) and mineral N uptake (Vmax2, Vmax1). The impact of these parameters on competition in a mixture was further analysed by examining their effects on the acquisition of limiting resources (Supplementary Data Fig. S2). This confirmed that the parameters affecting species balance were those with significant effects on light and/or soil N capture efficiency. Interestingly, the parameters with the strongest impact on mixture balance (q, Phyllo1, LmaxIn, del50In, FixMax) generally affected both competition for light and soil mineral N. Some parameters were more specific to light (e.g. LmaxL) or mineral N (e.g. Vmax2, Dldm, Dmax, Vmax1) competition, the latter being those with the weakest influence on mixture balance.

As a result of this sensitivity analysis, four model parameters (i.e. the most sensitive for each of the four physiological functions) were selected on the basis of their effects on total productivity in a binary mixture and resource competition. These parameters belonged to the phenotypic axes listed in Table 1 that represented growth kinetics (q), light acquisition (LmaxIn), mineral N acquisition (Vmax2) and radiation use efficiency (RUE). Parameters involved in N stress responses had little effect on model outputs under the conditions tested and were not considered in subsequent analyses.

Impact of soil N fertility and legume introduction on the neutral situation of competition in mixed stands

To analyse the impact of trait combinations on mixture performance, a neutral situation of competition was defined for binary mixtures with and without legumes (i.e. perfect trait convergence between the companion species: all parameters with identical values except for FixMax in legume-based mixtures). Figure 3 presents these neutral situations of competition in the different N fertility scenarios tested. In the absence of N-fixing species (Fig. 3A–C), this perfect trait convergence was equivalent to a mono-specific stand, so the sowing proportion had no effect on the total yield of the mixture and total yield was always equal to the average of the two pure stands (i.e. zero overyielding). Soil N fertility affected the two species in the same way (i.e. annual yield increasing from 450 to 1450 g m−2 between 0N and 300N treatments for non-legume stands) and the total yield of the mixtures remained unchanged irrespective of sowing proportions. Apparent overyielding (aOY) was also equal to actual overyielding (OY) irrespective of sowing proportions and N levels (Supplementary Data Fig. S3).

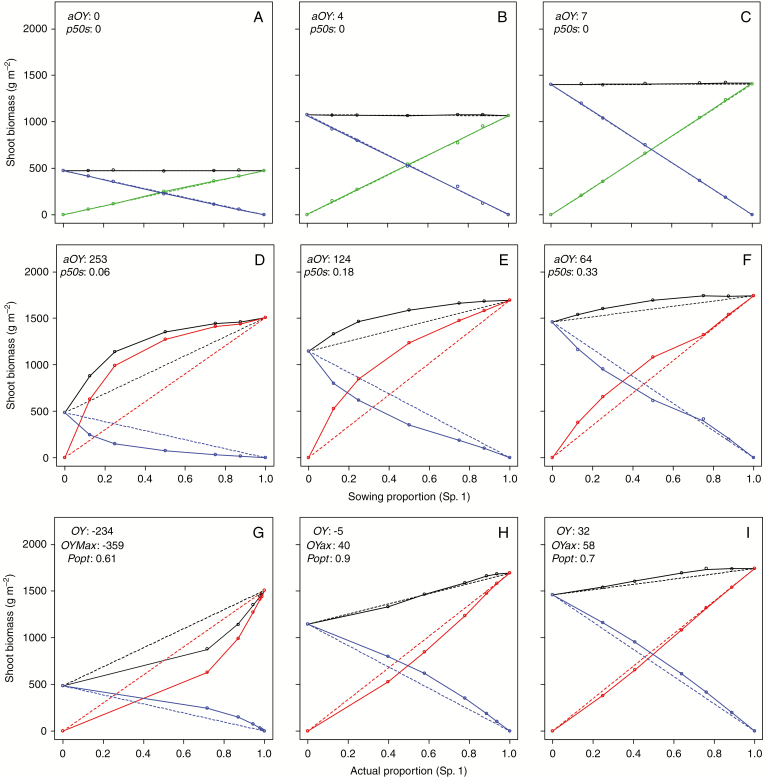

Fig. 3.

Variations in total yields (black) and partial yields of species with a binary mixture representing a neutral situation of competition between two non-legumes (green and blue) or a legume (red) and non-legume (blue) (i.e. exactly the same trait value, except for N fixation) tested using Wit’s replacement design. Panels ADG, BEH and CFI are for 0N, 120N and 400N treatments, respectively. The dashed lines represent the yields that would be achieved proportionally to the pure crop yields. Each point is the average of five simulations.

By contrast, in legume-based mixtures the two species behaved quite differently with respect to N responses (Fig. 3D–F). Irrespective of the N treatments, pure legume stands showed higher productivity than non-legume stands (i.e. annual yield increasing from 1500 to 1650 g m−2 between 0N and 400N treatments). However, the differential of productivity between the two pure species decreased in line with N fertilization from ~1000 g m−2 at 0N to <200 g m−2 at 120N. Remarkably, for all N treatments and species proportions, the neutral model of a legume-based mixture systematically achieved a total dry matter production that was higher than expected from the weighted average of the pure species stands computed at sowing. The average was maximum in the absence of fertilization (253 g m−2 at 0N), still significant under moderate N (124 g m−2 at 400N) but quite low under high N (64 g m−2 at 300N). In all these situations, aOY resulted from an increase in legume production and proportion. Thus, aOY was also associated with an imbalance in the mixture that tended to shift towards an increased proportion of the legume species under low N (i.e. p50s increasing from 0.66 to 0.95 between 400N and 0N). By contrast, the actual overyielding () of this neutral model was minimum, and even negative, under low N (−234 g m−2), almost equal to zero under moderate N and maximum under high N fertilization (32 g m−2, Fig. 3G–I). This indicates that the increase in legume proportion which was noted with such a convergent mixture was not able to overcompensate for the simulated reduction of production by the non-legume in all situations, and more particularly under scarce mineral N availability.

Impact of soil N fertility and species proportion on overyielding achieved by mixed stands

Figure 4 compares the overyielding achieved by the binary mixtures tested vs. their respective neutral situations of competition. In the absence of N-fixing species (Fig. 4A–C), the aOY and OY values were equal to their difference from the neutral model (because zero overyielding was found for the neutral model) and showed a similar overall response to N and sowing proportions (not shown). The distribution of aOY and OY values in these situations changed with N fertility levels. At low N, aOY was lower but almost always positive. At high N, aOY could be higher but the values were unevenly distributed, about half of the combinations resulting in negative aOY or OY (i.e. underyielding of the mixture).

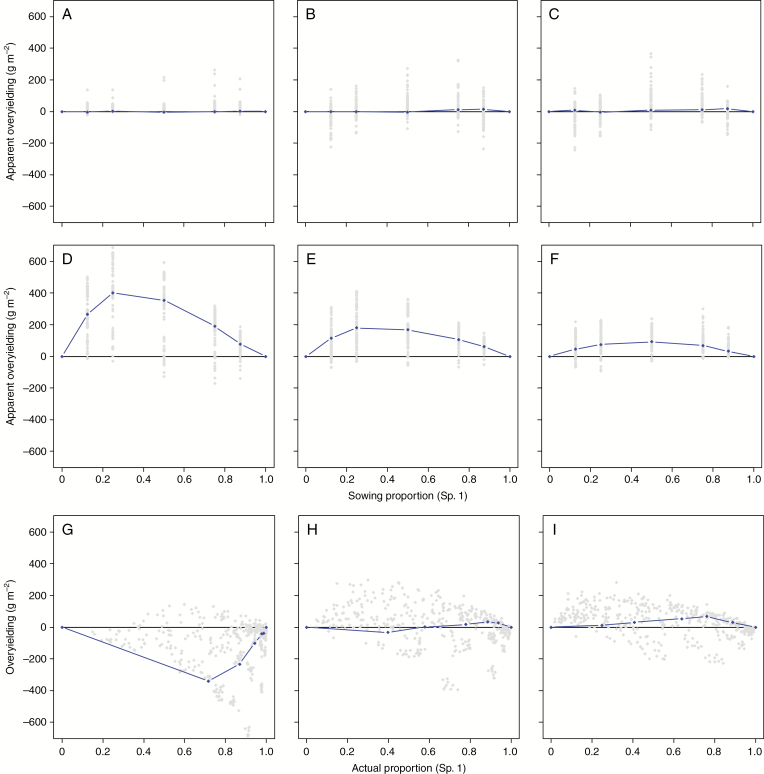

Fig. 4.

Variations in apparent overyielding (A–F) and actual overvielding (G–I) with respect to species proportions for binary mixtures of two non-legumes (A–C) or a legume and a non-legume (D–I). Apparent overyielding is expressed with respect to species proportion at sowing whereas actual overyielding is expressed against the biomass proportion at harvest. Panels ADG, BEH and CFI are for N0, N120 and N400 treatments, respectively. The blue line represents the neutral situation of competition in each situation.

Legume-based mixtures (Fig. 4D–F) presented a dramatically different picture. A positive aOY was almost systematically achieved, irrespective of N fertility levels. However, the magnitude of aOY was dependent on N availability. It ranged from 0 to 600 g m−2 at low N, but was limited to 300 g m−2 at high N. However, the difference from the neutral model in all situations showed that only about half of the binary mixtures tested performed better than a perfectly convergent mixture. This proportion was higher under high N (70 %) vs. low N (40 %) environments. The actual OY of legume-based mixtures displayed similar patterns at 400N, but very different results were obtained at low N, for which reduced (and frequently negative) OY (up to −500 g m−2) was noted compared to aOY. Despite the presence of legumes, most trait combinations actually produced less than expected from the proportions they achieved under these conditions. Nevertheless, many still produced more than the neutral model, which was negative at all proportions. Very low mineral N availability favoured legume development but at the same time limited the possibilities of complementarity regarding N sources. Trait combinations maximizing OY and with the highest frequency above the neutral model were found at intermediate N levels and achieved up to 250–300 g m−2.

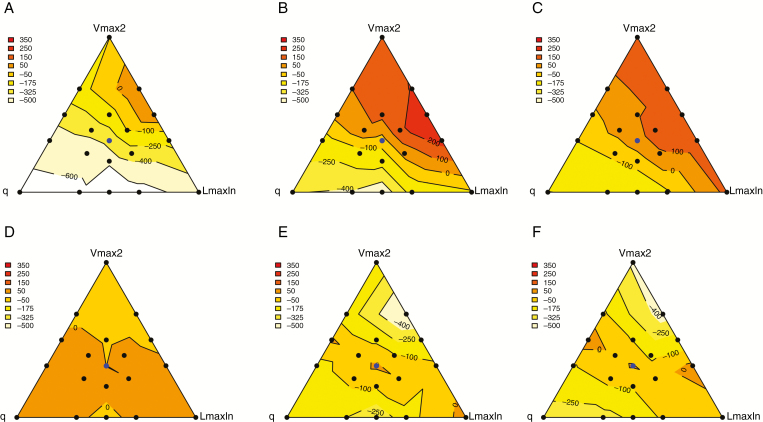

Impact of trait combinations on maximum overyielding in mixtures

Analysing the relationship between OY and trait combinations was achieved by projecting model outputs in triangular planes defined by the differences in parameter values between the mixed species, as described in Supplementary Data Fig. S1. In these projection planes, the neutral situation of competition is at the incentre of the triangle (i.e. all parameter differences equal to zero, blue point). Single parameter differences are represented on the internal angle bisectors, the largest differences in parameter values in favour of the reference species and associated species being at the corner and the centre of the opposite side, respectively. Because OYmax and were strongly correlated under all the scenarios (r2 > 0.96), only OYmax is presented here. In legume-based mixtures (Fig. 5A–C), the lowest OY performances occurred close to the q corner whereas the highest values were achieved close to the side opposite q, irrespective of N availability. This indicated that q differences, which shaped the response to temperature and the relative temporal growth of the mixed species, had the strongest impact on OYmax. Diverging temporal growth thus led to both the best and the worst situations. Within the range of situations tested, only divergences that led to a favoured establishment of the non-legume with respect to the legume enabled maximization of the outcome in terms of OY. OYmax values were also influenced in legume-based mixtures by the differences affecting the Vmax2 parameter. They were lower close to the side opposite Vmax2 and higher close to the Vmax2 corner (more particularly under 0N and 120N), indicating that the efficiency of mineral N uptake had to be divergent and in favour of the non-legume species to achieve the highest OY in N-limiting environments. Finally, differences in Len parameter values displayed weaker effects that changed slightly with N fertilization rates. The highest OYmax values were achieved at intermediate positions in the triangle (i.e. difference of parameter values close to zero) under 0N and 120N and closer to the Len corner with increasing N. For this latter parameter involved in vertical light competition, a convergence rather than a divergence of trait value appeared to favour OY performance of the mixture. These general conclusions were not affected by the fourth parameter studied, as no interaction between net RUE and the three other parameters were noted (Fig. S4). Light use efficiency essentially acted as a scaling factor for dry matter production and OYmax in these simulations.

Fig. 5.

Distribution of OYmax values in triangular planes summarizing the influence of q–Vmax2–LmaxIn parameters for legume-based mixtures (A–C) and binary mixtures without legumes (D–F) at 0N (A, D), 120N (B, E) and 400N (C, F). Data are for situations of convergent radiation use efficiency values between the two species.

The distributions of favourable combinations of traits in binary mixtures without legumes proved to differ markedly (Fig. 5D–F). As a general trend, the highest OYmax values were found on the bisector of the LmaxIn angle, and the lowest close to the Vmax2 and q corners. The overall triangular plane looked much more symmetrical with respect to the relative impact of the two mixed species and suggested that a balance had to be found between a degree of divergence for N acquisition in favour of one species and temporal growth or light competition in favour of the other in order to achieve OY.

Impact of trait combinations on the balance between species in mixtures

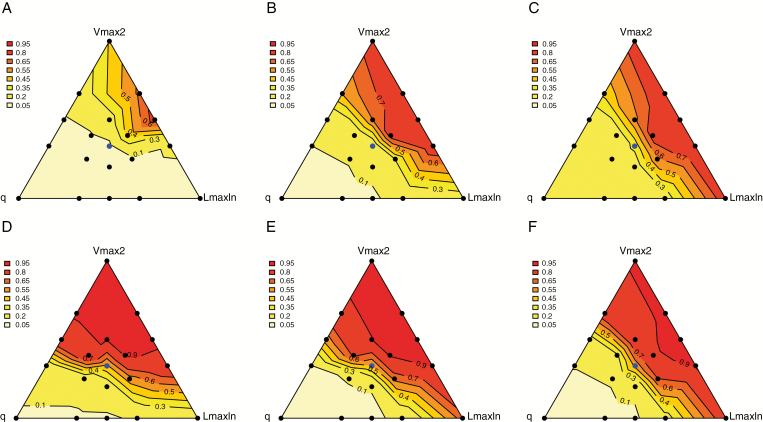

The impact of trait combinations on the stability of the mixtures assessed through p50s is presented in Fig. 6. In legume-based mixtures, stable situations (i.e. with a p50s of between 0.4 and 0.6) were found at positions that changed in line with the N fertilization level (Fig. 6A–C). They were close to the Vmax2 corner at 0N, and situated on a narrow band parallel to the side opposite the q corner at 120N and 400N. This band was closer to the q corner at high N. The majority of the triangular plane displayed unbalanced mixture situations shifting either in favour of the legume species (close to the q corner) or in favour of the non-legume species (side opposite the q corner). In mixtures without legumes (Fig. 6D–F), the balanced situations were all found close to the bisector of the LmaxIn corner. Remarkably, at 400N, the patterns of distribution for mixture balance appeared to be very similar between legume-based mixtures and mixtures without legumes, suggesting a weaker impact of N fixation on mixture composition under ample mineral N availability.

Fig. 6.

Distribution of the shift of species proportions assessed through p50s values in triangular planes summarizing the influence of q–Vmax2–LmaxIn parameters for legume-based mixtures (A–C) and binary mixtures without legumes (D–F) at 0N (A, D), 120N (B, E) and 400N (C, F). Data are for situations of convergent radiation use efficiency values between the two species.

The performances of mixtures were also examined in terms of species balance at maximum overyielding (pOpt, Supplementary Data Fig. S5). In legume-based mixtures, balanced situations at OYmax (i.e. with a 0.4–0.6 fraction of legumes) were found close to the incentre of the triangle representing the neutral situation of competition and at intermediate positions opposite the q corner. The majority of the triangular plane showed that OYmax was achieved for unbalanced mixtures, in favour of the legume species close to the q corner and in favour of the non-legume opposite the q corner.

DISCUSSION

Plant traits associated with performance in mixtures partly differed from sole crops

There is a long-standing debate regarding the need to select specific plant phenotypes for use in crop mixtures (Hill, 1996; Davies, 2001; Litrico and Violle, 2015; Maamouri et al., 2017; Annicchiarico et al., 2019). Whereas in practice, grassland species are selected on the basis of their performance in monospecific stands, their actual use is mostly in mixtures (Capitaine et al., 2008). The hypothesis underlying this practice is that a good variety in monoculture will also be a good variety in a mixture (Charles and Lehmann, 1989), and that important plant traits favourable in one particular condition will also be favourable in the other. The results of our sensitivity analysis highlighted consistent trait rankings in pure and mixed stands regarding the whole community productivity. The major sensitive traits identified for pure crops were also consistent with those reported for dynamic crop models based on similar modelling principles (e.g. STICS, Ruget et al., 2002): a strong influence of phenology (temperature response, q), leaf area deployment (phyllo1, LmaxL) and radiation use efficiency (RUE, NODcost) was noted. Remarkably, model outputs at the community level were less sensitive to variations in parameter values in mixed stands, consistent with numerous reports of more stable community productivity in mixtures compared to sole crops (Tilman et al., 2006; Prieto et al., 2015). The companion species plasticity acted as a buffer to any changes to the parameters tested in the target species, reducing the influence of this parameter at the community level (i.e. about 0.50 reduction for a 50/50 mixture). By contrast, our results also clearly showed that the partial yields of mixture components, and hence the composition of the community, were more sensitive to parameter variations than sole crops. The parameters that were sensitive in pure stands were also sensitive in mixtures, but a range of new parameters appeared to exert a strong influence on modulating the balance between species. These parameters had little effect on whole-community productivity, but were all linked to the relative competitive ability of the tested species with respect to their neighbours. They had an impact through the partitioning of resources (light and soil mineral N) between the mixture components. For instance, internode length (LmaxIn) and the delay in internode expansion (del50In) affected the vertical distribution of leaf area, which is one of the most important factors determining light partitioning in plant canopies (Louarn et al., 2012). Similarly, the maximum absorption rate by nitrate transporters (Vmax2) was found to strongly affect mineral N acquisition, as reported by Ruget et al. (2002). The branching ability of roots (DlDm), which affects both total root density and its vertical distribution in the root profile (Pagès et al., 2014; Faverjon et al., 2019b), also had a marked effect on the rate of soil resource acquisition. These ‘new’ traits, accounting for relative plant competitive ability, and thus acting mainly in a mixture, need to be considered in selection schemes and for assembly rules if these conditions are targeted. Some of these traits may already have been taken into account indirectly by breeders (e.g. plant height, integrating internode length and Lin parameter, is a proxy for above-ground production in pure stands of many species; Volenec et al., 1987), but most are yet to be integrated. This is most likely the case of root traits that have received less attention (Lynch, 2007) and where a degree of independence from shoot traits is now recognized (Dubabin et al., 2003; Faverjon et al., 2019b).

These results were obtained using alfalfa calibration as a reference during the sensitivity analysis, with a range of parameter variations broadly defined from inter-specific variability in forage species. As a result, the sensitive parameters identified might be more specific of the morphology and functioning of this species. Nevertheless, a degree of genericity could be expected from this analysis regarding the important processes at work to control plant interactions in intercrops. This is supported by the key traits currently used to select white clover in mixtures and consistent with our findings (Annicchiarico, 2003): vertical competition for light (through selection for petiole length; equivalent to LmaxIn) and regrowth vigour (i.e. related to earliness and stolon development; equivalent to q and phyllo1) were indeed identified empirically. The OAT method used during the sensitivity analysis presents the obvious limitation of not testing possible interactions between the parameters. Complementing the study with a global sensitivity approach could allow us to identify faster important trait combinations (Saltelli et al., 2000). Future work should also target systems more narrowly defined at the specific level in order to tackle a more realistic parameter space in mixture (e.g. alfalfa–tall fescue in Maamouri et al., 2017) while considering the range of parameter variability that is actually available to each species (e.g. for the q parameter: large interspecific variability, but low intraspecific variability; Zaka et al., 2017).

A simple divergence of trait values was not sufficient to ensure positive OY in legume-based mixtures

One of the most interesting features of modelling approaches is that they enable the use of theoretical references against which it is possible to benchmark actual observations and virtual experiments. For instance, the development of dynamic crop models has paved the way towards model-assisted ‘yield gap analysis’, which has helped the ranking of limiting factors in various crop production systems (Van Ittersum et al., 2013). Similarly, in ecology, the use of neutral models has been promoted to test the role of stochastic and ecological processes in community assembly (Chave, 2004; Gotelli and McGill, 2006). The modelling approach used during this study to simulate the functioning of plant communities enabled us to define a reference situation that respected the main assumptions of a neutral model of community assembly, namely: (1) neutrality could be defined at the individual plant level, and (2) all individuals in the community were assumed to be equivalent regarding their prospects for growth, reproduction and death (Chave, 2004). This situation corresponded to the case of a perfectly convergent binary mixture (i.e. all individuals with exactly the same parameter values) in our analysis. It produced the expected pattern of pure species behaviour in a de Wit’s replacement design, with no OY and no modifications to the species balance generated by a change to the mixture proportions (Fig. 2A–C). Remarkably, the same behaviour was found regarding neutral models defined by mixing two non-legumes or two legumes together (not shown). On the other hand, when setting just one of the two species as a fixing legume and the other as a perfectly equivalent non-legume, the thus-defined neutral model produced a dramatically different response to the mixture proportion and displayed systematic positive aOY values that were related to legume dominance under low and moderate N (Fig. 2D–F). Nevertheless, the actual OY appeared to be positive with this perfectly convergent mixture only at 120N and 400N. Affecting N fixation induced changes in N cycling that were sufficient to render OY only with a minimum soil N level being available to support niche separation for N. Moreover, introducing further divergent traits regarding both light and mineral N acquisition could produce mixtures with a higher or lower OY relative to the neutral model. At all N levels, it was possible to completely offset the minimum OY permitted by the neutral model and achieve a negative OY by choosing the worst combinations of divergent traits. This demonstrates that assembling mixture components on the basis of trait divergence for resource acquisition is a risky strategy if applied blindly to legume-based mixtures, supporting preliminary empirical evidence (Turnbull et al., 2005). At least, the strategy is not a sufficient criterion to ensure the assemblage of a community with good performance. To explain this, our results suggest that the two components played an asymmetric role in the functioning of the legume-based mixture and that an important part of OY was directly related to the N-fixing ability of legumes which had to be preserved, and was even reinforced because of the competition exerted by neighbouring species. Thus, acting on the same trait, but favouring one or other of the species, could produce opposing and asymmetric responses by the mixture, making it very important to affect positively the mixture component that has the strongest influence. This had previously been noted with respect to light competition, where the tallest species was shown to have dramatically more effect on light partitioning in the mixture than the subordinate species (Barillot et al., 2014). Although purely theoretical, the neutral models used in this study provided valuable references to assist with clarifying the strength and sense of the variations needed for the major plant traits in mixture under different growing conditions. It defined an objective minimum OY threshold, potentially different from zero and adapted to the mixed species and growing conditions, against which it would become possible to quantify the impact of trait combinations (de Bello, 2012).

Non-random trait assembly: adapting the differentials of trait values to the targeted environment and neighbouring species

For each growing condition, a large number of trait combinations produced OY values that were higher than the minimum line defined by the neutral model (consistent with Beckage and Gross, 2006). The OYmax values predicted in these situations ranged from ~0 to 100–300 g m−2 year−1 depending on the N level, consistent with experimental reports on mixed grasslands (e.g. 0–400 g m−2 in Finn et al., 2013; 150–450 g m−2 in Nyfeler et al., 2009). Furthermore, the response to the proportion of legumes (i.e. maximum impact within the 40–70 % range) and N fertilization rates (maximum OY response under moderate N fertilization) were also in line with existing syntheses (Nyfeler et al., 2009; Fitton et al., 2019), thus suggesting the model satisfactorily captures the processes at work and the patterns resulting from competition for light and N.

The combinations of traits that achieved the highest OY appeared to differ depending on the growing conditions. Temporal complementarity between the species (assessed through differences in the q parameter) exerted the strongest influence under all the N scenarios, confirming its potential role regarding community productivity highlighted by several field experiments (e.g. Morin et al., 2014; Husse et al., 2016; Meilhac et al., 2019). However, in our simulations, the effect of asynchronous development was only associated with positive OYmax values when diverging trait values resulted in earlier grass/non-legume development. This conclusion was in line with empirical evidence on sown grasslands, where associating Southern varieties of grasses with Northern legume varieties has been shown to boost mixture yield compared to mixtures of the same origin (Gastal et al., 2015). The second axis of niche differentiation concerned the acquisition of mineral N (through differences in the Vmax2 parameter), and only displayed positive effects on OYmax when diverging trait values favoured N acquisition by the non-legume. Because legumes can fix atmospheric N, this could have been expected from niche theory (Silvertown and Law, 1987). It strongly supports the idea of a beneficial specialization of N foraging on different resources by the intercrop species in legume-based mixtures (Corre-Hellou et al., 2006). Finally, the third axis, which analysed spatial light acquisition (through LmaxIn), did not demonstrate any positive effects of trait divergence on OY. On the contrary, mixtures that were balanced in terms of plant height performed better than the most divergent mixtures. Due to the negative effect of N limitation on shoot growth and development (which was a plastic response taken into account by the model; Faverjon et al., 2019a), this implied that different LmaxIn values achieved this balance at different N fertility levels and that the best performing combination of traits changed depending on N fertility. Chauvet et al. (2017) reached similar conclusions with respect to forest communities where they found assembly rules to be driven by a convergence of the traits involved in light competition, this effect being stronger on sites with fertile soils. A dispersion of shoot growth traits could indeed induce competitive exclusion and reduce diversity in plant communities (Fukami et al., 2005; Herben and Goldberg, 2014).

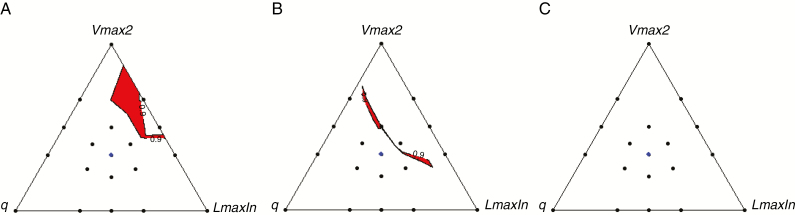

Overall, the best combinations of traits to favour OY in legume-based mixtures were not necessarily found for divergent trait values (i.e. convergence of canopy height), and when divergence mattered, it was not applied at random on the two species. They were not found either with trait combinations presenting the greatest mixture stability, but were positively associated with mixtures shifting towards non-legume dominance (i.e. declining legume proportions). In all conditions, high OY values were indeed sustained by the capacity of the mixture to increase N cycling and nitrogen overyielding (OYN), much more than with the N fixation capacity of the legume (Supplementary Data Fig. S6). This is in line with empirical results which suggested that more recycling of N in favour of non-legumes improved mixture performance in mixed grasslands (e.g. Beuselink et al., 1994; Louarn et al., 2015). Nevertheless, a multi-criterion analysis showed that an intersection domain did exist at low and moderate N levels when designing binary mixtures that were both relatively stable and efficient with respect to resource use and forage production (Fig. 7). The two domains differed between N levels, and also proved different from mixtures with an equivalent non-legume as a neighbour (not shown). At high N, the two criteria finally appeared to be mutually exclusive, offering no solution to the productivity–stability trade-off and indicating that significant OY could only be achieved at the expense of a marked legume decline under high N availability (Nyfeler et al., 2009).

Fig. 7.

Distribution of parameter combinations matching both mixture stability (p50s in the 0.4–0.6 range) and high overyielding (top quartile of OYmax) in legume-based mixtures projected in the triangular plane summarizing the influence of q- q–Vmax2–LmaxIn parameters at 0N (A), 120N (B) and 400N (C). Data include all possible combinations with the radiation use efficiency parameter.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite the obvious limitations of such a modelling exercise (Passioura, 1996), the heuristic value conferred by FSPMs to infer plant–plant interactions and break down complex phenotypes into a set of measurable traits can assist us in reinforcing logical and quantitative thinking in the design of assembly rules and selection methods for intercropping systems. For instance, the assumption of maximal trait divergence within a local pool of species, which is sometimes promoted as a rule of thumb to maximize complementarity between species in sown grasslands, was shown to perform poorly in legume-based mixtures. Similarly, the simulation results showed that the trait that mattered the most to control mixture proportion (i.e. interaction traits) were different from those displaying the most influence on yield in pure stands. Linking multi-criterion achievements as illustrated in this study (e.g. productivity, persistency and stability in the composition) with trait composition could lay the foundations for the definition of mixture ideotypes that may differ from those used in pure crops (Evers et al., 2018; Gaudio et al., 2019). Assuming a stable mixture could be found, the modelling approach could also help to screen favourable management options as illustrated here by the results for moderate N fertilization.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at https://academic.oup.com/aob and consist of the following.

Fig. S1: Illustration of the 19 trait combinations sampled in a triangular plane defined by parameters Vmax2, LmaxIn and q.

Fig. S2: Main effects of individual plant parameters on variations in light interception efficiency and mineral N uptake efficiency in a binary mixture.

Fig. S3: Variations in total yields and partial yields of species with a binary mixture.

Fig. S4: Distribution of OYmax values and p50s values in triangular planes.

Fig. S5: Distribution of pOpt values, the species proportion achieved at maximum overyielding, in triangular planes.

Fig. S6: Relationships between the different criteria used to assess virtual mixture performance.

FUNDING

This study was supported by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (PRAISE project, ANR-13-BIOADAPT-0015) and INRA’s Environment and Agronomy Division (IMPULSE Project).

LITERATURE CITED

- Annicchiarico P. 2003. Breeding white clover for increased ability to compete with associated grasses. The Journal of Agricultural Science 140: 255–266. [Google Scholar]

- Annicchiarico P, Collins RP, De Ron AM, Firmat C, Litrico I, Hauggaard-Nielsen H. 2019. Do we need specific breeding for legume-based mixtures? Advance in Agronomy 157: 141–215. [Google Scholar]

- Altieri MA, Nicholls CI, Henao A, Lana MA. 2015. Agroecology and the design of climate change-resilient farming systems. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 35: 869–890. [Google Scholar]

- Baldissera TC, Frak E, de Faccio Carvalho PC, Louarn G. 2014. Plant development controls leaf area expansion in alfalfa plants competing for light. Annals of Botany 113: 145–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barillot R, Escobar-Gutiérrez AJ, Fournier C, Huynh P, Combes D. 2014. Assessing the effects of architectural variations on light partitioning within virtual wheat–pea mixtures. Annals of Botany 114: 725–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barot S, Allard V, Cantarel A, et al. 2017. Designing mixtures of varieties for multifunctional agriculture with the help of ecology. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 37: 13. [Google Scholar]

- Baxevanos D, Tsialtas IT, Vlachostergios DΝ, et al. 2017. Cultivar competitiveness in pea–oat intercrops under Mediterranean conditions. Field Crops Research 214: 94–103. [Google Scholar]

- Beckage B, Gross LJ. 2006. Overyielding and species diversity: what should we expect? New Phytologist 172: 140–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedoussac L, Journet E-P, Hauggaard-Nielsen H, et al. 2015. Ecological principles underlying the increase of productivity achieved by cereal-grain legume intercrops in organic farming. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 35: 911–935. [Google Scholar]

- Bélanger G, Gastal F, Warembourg FR. 1994. Carbon balance of tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea Schreb.): effects of nitrogen fertilization and the growing season. Annals of Botany 74: 653–659. [Google Scholar]

- Brisson N, Launay M, Mary B, Beaudoin N. 2008. Conceptual basis, formalisations and parameterization of the STICS crop model. Versailles: Quae Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Brooker RW, Bennett AE, Cong WF, et al. 2015. Improving intercropping: a synthesis of research in agronomy, plant physiology and ecology. New Phytologist 206: 107–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitaine M, Pelletier P, Hubert F. 2008. Les prairies multispécifiques en France: histoire, réalités et valeurs attendues. Fourrages 194: 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Charles JP, Lehmann J. 1989. Intérêt des mélanges de graminées et de légumineuses pour la production fourragère en Suisse. Fourrages 119: 311–320. [Google Scholar]

- Chauvet M, Kunstler G, Roy J, Morin X. 2017. Using a forest dynamics model to link community assembly processes and traits structure. Functional Ecology 31: 1452–1461. [Google Scholar]

- Chave J. 2004. Neutral theory and community ecology. Ecology Letters 7: 241–253. [Google Scholar]

- Corre-Hellou G, Fustec J, Crozat Y. 2006. Interspecific competition for soil N and its interaction with N2 fixation, leaf expansion and crop growth in pea–barley intercrops. Plant and Soil 282: 195–208. [Google Scholar]

- Davies A. 2001. Competition between grasses and legumes in established pastures. In: Tow PG, Lazenby A, eds. Competition and succession in pastures. Wallingford: CABI Publishing, 63–83. [Google Scholar]

- de Bello F. 2012. The quest for trait convergence and divergence in community assembly: are null‐models the magic wand? Global Ecology and Biogeography 21: 312–317. [Google Scholar]

- de Wit CT. 1960. On competition. Versl Landbouwkd Onderz 66: 1–82. [Google Scholar]

- Delfosse V, Le Maire A, Balaguer P, Bourguet W. 2015. A structural perspective on nuclear receptors as targets of environmental compounds. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 36: 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake JA. 1990. The mechanics of community assembly and succession. Journal of Theoretical Biology 147: 213–233. [Google Scholar]

- Duchene O, Vian JF, Celette F. 2017. Intercropping with legume for agroecological cropping systems: complementarity and facilitation processes and the importance of soil microorganisms. A review. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 240: 148–161. [Google Scholar]

- Dunbabin V, Diggle A, Rengel Z. 2003. Is there an optimal root architecture for nitrate capture in leaching environments? Plant, Cell & Environment 26: 835–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers JB, Van Der Werf W, Stomph TJ, Bastiaans L, Anten NP. 2018. Understanding and optimizing species mixtures using functional–structural plant modelling. Journal of Experimental Botany 70: 2381–2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosse G, Varlet-Grancher C, Bonhomme R, Chartier M, Allirand JM, Lemaire G.. 1986. Maximum dry matter production and solar radiation intercepted by a canopy. Agronomie 6: 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Faverjon L, Escobar-Gutiérrez AJ, Litrico I, Louarn G. 2017. A conserved potential development framework applies to shoots of legume species with contrasting morphogenetic strategies. Frontiers in Plant Science 8: 405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faverjon L, Escobar-Gutiérrez A, Litrico I, Julier B, Louarn G. 2019a A generic individual-based model can predict yield, nitrogen content, and species abundance in experimental grassland communities. Journal of Experimental Botany 70: 2491–2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faverjon L, Escobar-Gutiérrez A, Pagès L, Migault V, Louarn G. 2019b Root growth and development do not directly relate to shoot morphogenetic strategies in temperate forage legumes. Plant and Soil 435: 277–294. [Google Scholar]

- Finn JA, Kirwan L, Connolly J, et al. 2013. Ecosystem function enhanced by combining four functional types of plant species in intensively managed grassland mixtures: a 3‐year continental‐scale field experiment. Journal of Applied Ecology 50: 365–375. [Google Scholar]

- Fitton N, Bindi M, Brilli L, et al. 2019. Modelling biological N fixation and grass-legume dynamics with process-based biogeochemical models of varying complexity. European Journal of Agronomy 106: 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Fukami T, Martijn Bezemer T, Mortimer SR, van der Putten WH. 2005. Species divergence and trait convergence in experimental plant community assembly. Ecology Letters 8: 1283–1290. [Google Scholar]

- Gaba S, Lescourret F, Boudsocq S, et al. 2015. Multiple cropping systems as drivers for providing multiple ecosystem services: from concepts to design. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 35: 607–623. [Google Scholar]

- Gastal F, Fernandez L, Louarn G, et al. 2015. Les mélanges de variétés méditerranéennes/tempérées comme stratégie d’adaptation des espèces fourragères au changement climatiques? In: Durand J-L, Enjalbert J, Hazard L, et al., eds. Actes Du Colloque Présentant Les méthodes Et résultats Du Projet Climagie, 223. Poitiers: INRA Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudio N, Escobar-Gutiérrez AJ, Casadebaig P, et al. 2019. Current knowledge and future research opportunities for modeling annual crop mixtures. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 39: 20. [Google Scholar]

- Gautier H, Měch R, Prusinkiewicz P, Varlet-Grancher C. 2000. 3D architectural modelling of aerial photomorphogenesis in white clover (Trifolium repens L.) using L-systems. Annals of Botany 85: 359–370. [Google Scholar]

- Gotelli NJ, McGill BJ. 2006. Null versus neutral models: what’s the difference? Ecography 29: 793–800. [Google Scholar]

- Götzenberger L, de Bello F, Bråthen KA, et al. 2012. Ecological assembly rules in plant communities—approaches, patterns and prospects. Biological Reviews 87: 111–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goutiers V, Moirez-Charron MH, Deo M, Hazard L. 2016. Capflor (R): a tool for designing species mixtures and thus creating diversified grasslands. Fourrages 228: 243–252. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton NRS. 1994. Replacement and additive designs for plant competition studies. Journal of Applied Ecology 31: 599–603. [Google Scholar]

- Harper JL. 1977. Population biology of plants. London: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Herben T, Goldberg DE. 2014. Community assembly by limiting similarity vs. competitive hierarchies: testing the consequences of dispersion of individual traits. Journal of Ecology 102: 156–166. [Google Scholar]

- Hill J. 1996. Breeding components for mixture performance. Euphytica 92: 135–138. [Google Scholar]

- Husse S, Huguenin-Elie O, Buchmann N, Lüscher A. 2016. Larger yields of mixtures than monocultures of cultivated grassland species match with asynchrony in shoot growth among species but not with increased light interception. Field Crops Research 194: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Jeuffroy MH, Biarnès V, Cohan JP, et al. 2015. Performances agronomiques et gestion des légumineuses dans les systèmes de productions végétales. In: Schneider A, Huyghe C, eds. Les légumineuses pour des systèmes agricoles et alimentaires durables. France: Editions Quae, 139–223. [Google Scholar]

- Kortenkamp A, Altenburger R. 1999. Approaches to assessing combination effects of oestrogenic environmental pollutants. Science of the Total Environment 233: 131–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Tilman D, Lambers H, Zhang F-S. 2014. Plant diversity and overyielding: insights from belowground facilitation of intercropping in agriculture. New Phytologist 203: 63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lithourgidis AS, Dordas CA, Damalas CA, Vlachostergios DN. 2011. Annual intercrops: an alternative pathway for sustainable agriculture. Australian Journal of Crop Science 5: 396–410. [Google Scholar]

- Litrico I, Violle C. 2015. Diversity in plant breeding: a new conceptual framework. Trends in Plant Science 20: 604–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louarn G, Corre-Hellou G, Fustec J, et al. 2010. Déterminants écologiques et physiologiques de la productivité et de la stabilité des associations graminées-légumineuses. Innovations Agronomiques 11: 79–99. [Google Scholar]

- Louarn G, Da Silva D, Godin C, Combes D. 2012. Simple envelope-based reconstruction methods can infer light partitioning among individual plants in sparse and dense herbaceous canopies. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 166: 98–112. [Google Scholar]

- Louarn G, Escobar-Gutiérrez AJ, Migault V, Faverjon L, Combes D. 2014. “Virtual grassland”: an individual-based model to deal with grassland community dynamics under fluctuating water and nitrogen availability. Grassland Science in Europe 19: 242–244. [Google Scholar]

- Louarn G, Pereira-Lopès E, Fustec J, et al. 2015. The amounts and dynamics of nitrogen transfer to grasses differ in alfalfa and white clover-based grass-legume mixtures as a result of rooting strategies and rhizodeposit quality. Plant and Soil 389: 289–305. [Google Scholar]

- Louarn G, Faverjon L, Migault V, Escobar-Gutiérrez AJ, Combes D. 2016. Assessment of ‘3DS’, a soil module for individual-based models of plant communities. In: IEEE International Conference on Functional-Structural Plant Growth Modeling, Simulation, Visualization and Applications (FSPMA), Qingdao, 2016, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Louarn G, Faverjon L. 2018. A generic individual-based model to simulate morphogenesis, C–N acquisition and population dynamics in contrasting forage legumes. Annals of Botany 121: 875–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüscher A, Mueller‐Harvey I, Soussana JF, Rees RM, Peyraud JL. 2014. Potential of legume‐based grassland–livestock systems in Europe: a review. Grass and Forage Science 69: 206–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JP. 2007. Roots of the second green revolution. Australian Journal of Botany 55: 493–512. [Google Scholar]

- Maamouri A, Louarn G, Gastal F, Béguier V, Julier B. 2015. Effects of lucerne genotype on morphology, biomass production and nitrogen content of lucerne and tall fescue in mixed pastures. Crop and Pasture Science 66: 192–204. [Google Scholar]

- Maamouri A, Louarn G, Béguier V, Julier B. 2017. Performance of lucerne genotypes for biomass production and nitrogen content differs in monoculture and in mixture with grasses and is partly predicted from traits recorded on isolated plants. Crop and Pasture Science 68: 942–951. [Google Scholar]

- Malézieux E, Crozat Y, Dupraz C, et al. 2009. Mixing plant species in cropping systems: concepts, tools and models: a review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 29: 43–62. [Google Scholar]

- Meilhac J, Durand JL, Beguier V, Litrico I. 2019. Increasing the benefits of species diversity in multispecies temporary grasslands by increasing within-species diversity. Annals of Botany 123: 891–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migault V. 2015. Insertion de la morphogenèse racinaire dans L-grass, un modèle structure-fonction de graminées fourragères. PhD Thesis, Poitiers University. [Google Scholar]

- Morin X, Fahse L, de Mazancourt C, Scherer‐Lorenzen M, Bugmann H. 2014. Temporal stability in forest productivity increases with tree diversity due to asynchrony in species dynamics. Ecology Letters 17: 1526–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosimann E, Frick R, Suter D, Rosenberg E. 2012. Mélanges standard pour la production fourragère - revision 2013–2016. Recherche Agronomique Suisse 3: 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CJ. 2000. Shoot morphological plasticity of grasses: leaf growth vs. tillering. Grassland Ecophysiology and Grazing Ecology 101–126. [Google Scholar]

- Nyfeler D, Huguenin‐Elie O, Suter M, Frossard E, Connolly J, Lüscher A. 2009. Strong mixture effects among four species in fertilized agricultural grassland led to persistent and consistent transgressive overyielding. Journal of Applied Ecology 46: 683–691. [Google Scholar]

- Nyfeler D, Huguenin-Elie O, Suter M, Frossard E, Lüscher A. 2011. Grass–legume mixtures can yield more nitrogen than legume pure stands due to mutual stimulation of nitrogen uptake from symbiotic and non-symbiotic sources. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 140: 155–163. [Google Scholar]

- Pagès L, Bécel C, Boukcim H, Moreau D, Nguyen C, Voisin AS. 2014. Calibration and evaluation of ArchiSimple, a simple model of root system architecture. Ecological Modelling 290: 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Pagès L. 2016. Branching patterns of root systems: comparison of monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous species. Annals of Botany 118: 1337–1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passioura JB. 1996. Simulation models: science, snake oil, education, or engineering? Agronomy Journal 88: 690–694. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto I, Violle C, Barre P, Durand JL, Ghesquiere M, Litrico I. 2015. Complementary effects of species and genetic diversity on productivity and stability of sown grasslands. Nature Plants 1: 15033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusinkiewicz P, Lindenmayer A. 1990. The algorithmic beauty of plants. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Raseduzzaman M, Jensen ES. 2017. Does intercropping enhance yield stability in arable crop production? A meta-analysis. European Journal of Agronomy 91: 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ruget F, Brisson N, Delécolle R, Faivre R. 2002. Sensitivity analysis of a crop simulation model, STICS, in order to choose the main parameters to be estimated. Agronomie 22: 133–158. [Google Scholar]

- Saltelli A, Chan K, Scott EM. 2000. Sensitivity analysis. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Silvertown J, Law R. 1987. Do plants need niches? Some recent developments in plant community ecology. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2: 24–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinoquet H, Le Roux X, Adam B, Ameglio T, Daudet FA. 2001. RATP: a model for simulating the spatial distribution of radiation absorption, transpiration and photosynthesis within canopies: application to an isolated tree crown. Plant, Cell & Environment 24: 395–406. [Google Scholar]

- Tilman D, Reich PB, Knops JMH. 2006. Biodiversity and ecosystem stability in a decade-long grassland experiment. Nature 441: 629–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornley JHM. 2001. Simulating grass–legume dynamics: a phenomenological submodel. Annals of Botany 88: 905–913. [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull LA, Rahm S, Baudois O, Eicherberger-Glinz S, Wacker L, Schmid B. 2005. Experimental invasion by legumes reveals non‐random assembly rules in grassland communities. Journal of Ecology 93: 1062–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ittersum MK, Cassman KG, Grassini P, Wolf J, Tittonell P, Hochman Z. 2013. Yield gap analysis with local to global relevance—a review. Field Crops Research 143: 4–17. [Google Scholar]

- Vandermeer JH. 1989. The ecology of intercropping. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Voisin AS, Gastal F. 2015. Nutrition azotée et fonctionnement agrophysiologique spécifique des légumineuses. In: Scheider A, Huyghe C, eds. Les Légumineuses pour des systèmes agricoles et alimentaires durables. Versailles: Quae, 79–138. [Google Scholar]

- Volenec JJ, Cherney JH, Johnson KD. 1987. Yield components, plant morphology, and forage quality of Alfalfa as influenced by plant population. Crop Science 27: 321–326. [Google Scholar]

- Wezel A, Casagrande M, Celette F, et al. 2014. Agroecological practices for sustainable agriculture. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 34: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zaka S, Ahmed LQ, Escobar-Gutiérrez AJ, Gastal F, Julier B, Louarn G. 2017. How variable are non-linear developmental responses to temperature in two perennial forage species? Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 232: 433–442. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.