Abstract

Introduction

A rapidly evolving evidence suggests that smell dysfunction is a common symptom in COVID-19 infection with paucity of data on its duration and recovery rate.

Objectives

Delineate the different patterns of olfactory disorders recovery in patients with COVID-19.

Methods

This cross-sectional cohort study included 96 patients with olfactory complaint confirmed to be COVID-19 positive with recent onset of anosmia. All patients were inquired for smell recovery patterns using self-assessment questionnaires.

Results

Ninety six patients completed the study with mean age 34.26 ± 11.91 years. Most patients had sudden anosmia 83%. Loss of smell was accompanied by nonspecific inflammatory symptoms as low-grade fever (17%) and generalized body ache (25%). Nasal symptoms were reported by 33% of patients. Some patients reported comorbidities as D.M (16%), hypertension (8%) or associated allergic rhinitis (25%), different patterns of olfactory recovery showed 32 patients experiencing full recovery (33.3%) while, 40 patients showed partial recovery (41.7%) after a mean of 11 days while 24 patients (25%) showed no recovery within one month from onset of anosmia.

Conclusion

The sudden olfactory dysfunction is a common symptom in patients with COVID-19. Hyposmia patients recover more rapidly than anosmic ones while the middle age group carried the best prognosis in olfactory recovery. Females possess better potentiality in regaining smell after recovery and the association of comorbidities worsen the recovery rate of olfactory dysfunction in patients with COVID19.

Level of evidence

Level 2b a cross-sectional cohort study.

Keywords: Hyposmia, Anosmia, Smell disorders, COVID-19, Smell restoration, Corona virus

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19), caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus is a worldwide pandemic which was first reported in China on December 2019 [1]. Till the time of writing this article, more than 6 million confirmed cases are distributed around the globe [2]. The most reported symptoms are fever, cough, dyspnea, myalgia, arthralgia, headache, diarrhea, rhinorrhea, and sore throat [3]. The British association of otolaryngology has recently identified the sudden loss of sense of smell and taste as “significant symptoms” which were found even in the absence of other symptoms [4]. When patients were asked about smell and taste, 85.6% and 88% of them reported olfactory and gustatory dysfunction, respectively [5]. Unlike other viral infections, olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19 patients seems characteristic as it is not associated with rhinorrhea or any other nasal symptoms [5]. The post-viral olfactory dysfunction maybe conductive due to swelling of the mucosa in the olfactory cleft [6]. Nonetheless, the neuroinvasive, neurotropic, and neurovirulent properties of the virus may be able to produce neuronal impairment as well [7]. Treatment options include nasal saline irrigation, topical intranasal corticosteroids, topical nasal decongestants, vitamins and some trace elements [5]. Systemic steroids should be avoided as it may increase the severity of infection [4]. The data obtained from the few available reports suggest that most patients with anosmia or ageusia recovered within 3 weeks with tendency to persist for longer periods in young age groups [8]. Further studies are needed to figure out olfactory recovery in those patients with reviewing their characteristics.

1.1. Aim of the study

The aim of the study is to delineate the different patterns of olfactory disorders recovery in patients with COVID-19.

2. Patients & methods

The sample size was calculated by adjusting the power of the test to 80% and the confidence interval to 95% with margin of error accepted adjusted to 5% calculating sample size equation with 96 patients to take part in the study.

This is a cross-sectional cohort study conducted on 96 patients attending Tanta University hospital with recent olfactory complaint confirmed to be COVID-19(SARS-CoV-2) positive (using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, RT-PCR on nasopharyngeal sample, Cobas® 6800 System - Diagnostics Roche) adopted by the local health ministry. The study was done in April and May 2020 and approved by the Editorial Board Team & the Ethical Committee of Tanta University, Egypt with approval code 30215/04/20. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Written informed consents obtained from all participants before being included in the study.

All the participants (more than 18 years old) have been included in the study once the diagnosis with COVID-19 were confirmed whether subsequently admitted or house-bound.

We excluded anosmia patients with history of olfactory dysfunction, patients not confirmed to be COVID-19 positive, patients with history of nasal surgery or sinonasal tumors, intensive care patients, mentally confused, psychologically disturbed patients and illiterate patients.

Studied group was inquired for age, sex, history of general diseases, nasal disease, associated COVID-19 symptoms and smoking. All the participants were interrogated during regular medical visits on a weekly basis for four successive visits, in order to estimate the severity of these sensory dysfunction, we adopted a 10-item questionnaire. These items were adapted from the DyNaCHRON questionnaire [9].

Only those inquiring smell were used in our study. Each item was scored from 0 to 10. Zero was equivalent to absence of symptom and 10 to maximum symptom. Complete recovery was defined by a score between 0 and 5 out of 100. Partial recovery was defined by a score between 5 and the score obtained during the previous visit, no recovery by the 4th week was defined by a score equal or superior to the first score obtained during the 1st visit. We analyze different associated factors affecting the pattern of recovery and the time lapse between partial and complete recovery.

3. Results

Statistical presentation and analysis of the present study was conducted, using the mean, standard deviation, qualitative data was expressed as frequency (number and percentage) by chi-square test and multivariate logistic regression was used to adjust the confounding factors using data (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) where >0.05 non-significant, <0.05* significant and <0.001** highly significant.

96 patients completed the study. 65% were aged under 40 (Fig. 1 ). The mean age of patients was 34.26 ± 11.91 years. They were 56 females and 40 males. 16.7% of patients were smokers.

Fig. 1.

Age distribution of participants of the study.

Most patients had sudden anosmia (80 patients — 83%) while (16 patients — 17%) patients developed gradual loss of smell with 80% of patients had a previous history of contact with anosmic patients. Loss of smell was accompanied by nonspecific inflammatory symptoms as low-grade fever (17% of patients) and generalized body ache (25% of patients). Nasal symptoms (nasal obstruction, sneezing, coryza, purulent rhinorrhea, nasal pruritus and/or nasal burning) were reported by 33% of patients. Some patients reported comorbidities as D.M (16%), hypertension (8%) or associated allergic rhinitis (25%) (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

shows characteristics of COVID-19 patients with resolved or persistent olfactory dysfunction.

| Early recovery (within 1 month from onset) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partial |

Complete |

No recovery |

Chi-square |

|||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | X2 | P-value | |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| <20 | 14 | 35 | 2 | 6.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 60.547 | <0.001** |

| 20–<30 | 2 | 5 | 10 | 31.3 | 4 | 16.7 | ||

| 31–<40 | 16 | 40 | 15 | 46.9 | 1 | 4.2 | ||

| 40–<50 | 8 | 20 | 1 | 3.1 | 6 | 25.0 | ||

| ≥50 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 12.5 | 13 | 54.2 | ||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 24 | 60 | 23 | 71.9 | 7 | 29.2 | 10.557 | 0.005* |

| Male | 16 | 40 | 9 | 28.1 | 17 | 70.8 | ||

| Other COVID-19 manifestation | ||||||||

| Other COVID-19 symptoms | 9 | 22.5 | 2 | 6.3 | 23 | 95.8 | 51.032 | <0.001** |

| No | 31 | 77.5 | 30 | 93.8 | 1 | 4.2 | ||

| Family history of anosmia before or after | ||||||||

| Yes | 31 | 77.5 | 21 | 65.6 | 20 | 83.3 | 2.522 | 0.283 |

| No | 9 | 22.5 | 11 | 34.4 | 4 | 16.7 | ||

| History of general disease | ||||||||

| DM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 33.3 | 51.032 | <0.001** |

| HTN | 3 | 7.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 9 | 37.5 | ||

| No | 36 | 90 | 29 | 90.6 | 7 | 29.2 | ||

| History of nasal diseases | ||||||||

| Allergic | 3 | 7.5 | 2 | 6.3 | 19 | 79.2 | 50.089 | <0.001** |

| No | 37 | 92.5 | 30 | 93.8 | 5 | 20.8 | ||

| Smoking | ||||||||

| Yes | 4 | 10 | 2 | 6.3 | 10 | 41.7 | 14.580 | <0.001** |

| No | 36 | 90 | 30 | 93.8 | 14 | 58.3 | ||

>0.05 non-significant, <0.05* significant and <0.001** highly significant.

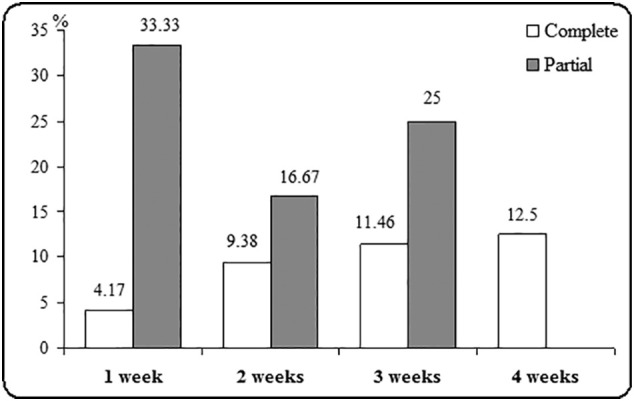

As regard to different patterns of olfactory recovery, 32 patients experienced full recovery (33.3%) while, 40 patients showed partial recovery within one month from loss of olfaction (41.7%) while 24 of patients showed no recovery within 1 month. When there was full recovery, the mean time from partial to complete recovery was 7 days with (SD 5.8). Patients olfactory alteration lasted more than one month in 25% of cases with no improvement. However, most of patients reported resolution of symptoms after a mean of 11 days (partial recovery), 17 days (complete recovery) with different characteristics of patients recovery pattern are shown in Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6 .

Fig. 2.

Duration of recovery from loss of olfaction in patients for COVID-19.

Fig. 3.

Recovery from loss of olfaction in patients for COVID-19 according to age.

Fig. 4.

Recovery from loss of olfaction in patients for COVID-19 according to sex.

Fig. 5.

Pattern of recovery of the patients.

Fig. 6.

Patterns of recovery in relation to comorbidities.

4. Discussion

It is now evident that smell and/or taste loss may be consistent accompanying symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Most observations suggest transient anosmia with recovery after days to weeks, but it remains unclear in how many cases this insult would be permanent [10].

The exact pathogenesis of olfactory upset in such patients is still ambiguous, however, SARS-CoV-2 seems to target non-neural cell types in the peripheral olfactory system rather than directly enter olfactory neurons, and it seems to be enough to generate subsequent harm that would in turn cause impairment of the olfactory neurons function altering the odor transduction which takes place on their cilia [11]. We strongly believe that the short-term COVID-19-linked anosmia reported throughout the literature is based on the hypothesis that SARS-CoV2 affects dramatically the olfactory epithelium, which can quickly renew and recover following the period of viral clearance [12].

In the present study, 96 patients completed the study. The mean age of patients was 34.26 ± 11.91 years 56 females (56.3%) and 40 males with evident female predominance, this goes in accordance with Kosugi et al. [13] who studied 183 olfactory patients of COVID-19 with mean age of 36 years and female predominance 53.1% of their patients, similarly, in a multicentric study of COVID-19 patients performed by Lechien et al. [5] 357 patients were recruited with mean age 37 years and female predominance 63.1%. we attribute this female predominance as regard to olfactory complaint to the fact that females have a greater concern for their health as well as the decreased capacity of men to perceive olfactory disorders [5,13].

In the current study, most patients had sudden anosmia (80 patients — 83%) while (16 patients — 17%) patients developed gradual loss of smell with 80% of patients had a previous history of contact with anosmic patients, olfactory upset was accompanied by nonspecific inflammatory symptoms as low-grade fever (17% of patients) and generalized body ache (25% of patients). Nasal symptoms were reported by 33% of patients. Some patients reported comorbidities as D.M (16%), hypertension (8%) or associated allergic rhinitis (25%), in the same vein a Brazilian study [13] reported sudden anosmia in 83.3% of patients with other nasal symptoms “rhinorrhea, pruritis” in 43.9% of their patients with fever in 49% of patients and myalgia& fatigue in 28% of the affected patients. Also, Beltran-Corbellini et al. [13] stated acute onset olfactory disorder in 71% of their patients with only (12.9%) reported concomitant nasal manifestations, in the same scope, the detailed study by Lechien et al., addressed fever in 48% of their cohort with myalgia in 59% of them, also, they expressed nasal obstruction & rhinorrhea in 32% & 37% of their patients [5,13,14].

In the current study, 32 patients experienced full recovery (33.3%) while, 40 patients showed partial recovery within one month from loss of olfaction (41.7%) however, 25% of patients showed no recovery within 4 weeks of onset. When there was full recovery, the mean time from partial to complete recovery was 7 days.

Hyposmia patients showed better recovery than those of complete anosmia especially in the 1st week of follow up 33.33% to 4.17% and we believe that is due to a lesser viral load in hyposmia patients with better status for viral clearing, our results prove to be compatible with Kosugi et al. [13]who reported that the full recovery from sudden hyposmia in positive-COVID-19 patients takes place more frequently than that from sudden anosmia, on the other hand Hopkins et al. [15], in a study with a similar design, showed that 80.1% of their patients with sudden olfactory dysfunction had some degree of olfactory recovery one week after the research, concluding that it is likely that the olfaction would recover well in this COVID-19 pandemic scenario. However, full recovery from sudden olfactory dysfunction was reported by only 11.5% of their patients, and only 5.3% of patients in the study were tested for COVID-19, making it early to extrapolate their results [13,15].

Also, the age group 31–40 years revealed a higher rate of olfactory recovery than other age groups, with 46.9% of total complete recovery and 40% of partial recovery lay in that age group, our results goes hand in hand with those results reported by Voinsky et al. [16] who reviewed 5769 patients and concluded that younger individuals, in addition to be less likely to have severe COVID-19 symptoms requiring intensive care unit hospitalization, are also recovering on average faster from SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Also, in the current study females represent more than 70% of those who completely recovered anosmia and 60% of our cohort who showed partial recovery, the exact aetiology for this sex difference remain unclear, and it has been suggested that this may reflect the fact that androgen hormones, which have higher plasma levels in males compared with females, enhance the transcription of TMPRSS2, the gene coding for the protease necessary for SARS-CoV-2 cell access following the biding of its spike protein to cell membrane ACE2 [17].

In our study, patients with associated COVID-19 symptoms and those suffering comorbidities are associated with a more delayed pattern of recovery than those who do not suffer same conditions, similarly, Wei-jie Guan et al. studied comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with COVID-19 in China and they concluded that diabetic and hypertensive patients would experience worse outcome (34.6% versus 14.3%) & (32.7% versus 12.6%) respectively of cases. They attributed their findings to their belief that those patients with coexisting comorbidities are more likely to have poorer baseline well-being with a reduced recovery potentiality [ (18)].

In the current study we offered no specific treatment for olfactory dysfunction that accompanies Covid-19 infection as early reports suggest rapid recovery within few weeks [15,19]. The European Rhinologic Society (ERS) and the ENT UK association advise against giving systemic corticosteroids to patients with sudden olfactory dysfunction since corticosteroids cause immune suppression by impairing the innate immunity, their use has been largely discouraged because of the fear of worsening of viral propagation [20] However, according to the ARIA-EEACI (Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma & European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology) statement, it is advised to continue intranasal corticosteroids in patients with allergic rhinitis. Even if they become infected by COVID-19, there is no evidence that this could lead to deterioration or a worse outcome [21]. On the other hand, some centers adopt using short course of oral steroid in patients with a persistent loss of smell.

related to COVID-19 and in those patients with persistent loss of sense of smell following covid-19 after at least two weeks since diagnosis, they believe that this protocol seems to give better outcomes than observation [22].

To our knowledge, this is the 1st Egyptian article discussing otorhinolaryngological manifestations of COVID-19 patients with detailed analysis of olfactory dysfunction and their pattern of recovery during COVID-19 pandemic, however, the present study may show some limitation as the authors did not adopt psycho-physical or objective maneuvers in evaluating olfactory dysfunction but we believe that this limitation does not detract from the statistical results obtained lightening different characteristics of patients recovery from this cruel pandemic disease.

5. Conclusion

The sudden olfactory dysfunction is a common symptom in patients with COVID-19. Hyposmia patients recover more rapidly than anosmia patients while the middle age group carried the best prognosis in olfactory recovery. Females possess better potentiality in regaining smell after recovery and the association of comorbidities worsen the recovery rate of olfactory dysfunction in patients with COVID-19.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent

Formal consent was signed by all the participant for sharing in this research.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding

The authors have no funding or financial relationships to disclose.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mohamed A. Amer: Writing - original draft, Formal analysis. Hossam S. El-Sherif: Writing - review & editing. Ahmed S. Abdel-Hamid: Data curation, Formal analysis. Saad El-Zayat: Methodology, Conceptualization, Investigation.

Declaration of competing interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard, WHO, viewed 03 June 2020. https://covid19.who.int

- 3.Young B.E., Ong S.W.X., Kalimuddin S. Epidemiologic features and clinical course of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Singapore. JAMA. 2020;323(15):1488–1494. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hopkins C., Surda P., Whitehead E., Kumar B.N. Early recovery following new onset anosmia during the COVID-19 pandemic — an observational cohort study. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;49(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s40463-020-00423-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lechien J.R., Chiesa-Estomba C.M., De Siati D.R. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild-to-moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multicenter European study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-05965-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seiden A.M., Duncan H.J. The diagnosis of a conductive olfactory loss. Laryngoscope. 2001;111(1):9–14. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200101000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meessen-Pinard M., Le Coupanec A., Desforges M., Talbot P.J. Pivotal role of receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 and mixed lineage kinase domain-like in neuronal cell death induced by the human Neuroinvasive coronavirus OC43. J Virol. 2016;91(1):e01513–e01516. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01513-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee Y., Min P., Lee S., Kim S.W. Prevalence and duration of acute loss of smell or taste in COVID-19 patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(18):e174. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kacha S., Guillemin F., Jankowski R. Development and validity of the DyNaChron questionnaire for chronic nasal dysfunction. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;269(1):143–153. doi: 10.1007/s00405-011-1690-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marinosci A., Landis B.N., Calmy A. Possible link between anosmia and COVID-19: sniffing out the truth. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-05966-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brann DH, Tsukahara T, Weinreb C, Lipovsek M, Van den Berge K, Gong B, et al. Non-neuronal expression of SARS-CoV-2 entry genes in the olfactory system suggests mechanisms underlying COVID-19-associated anosmia. bioRxiv. (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Yan C.H., Faraji F., Prajapati D.P., Boone C.E., DeConde A.S. Association of chemosensory dysfunction and Covid-19 in patients presenting with influenza-like symptoms. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/alr.22579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kosugi E.M., Lavinsky J., Romano F.R. Incomplete and late recovery of sudden olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;86(4):490–496. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beltrán-Corbellini Á., Chico-García J.L., Martínez-Poles J. Acute-onset smell and taste disorders in the context of COVID-19: a pilot multicentre polymerase chain reaction based case-control study. Eur J Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1111/ene.14273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hopkins C., Surda P., Whitehead E., Kumar B.N. Early recovery following new onset anosmia during the COVID-19 pandemic an observational cohort study. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;49:26. doi: 10.1186/s40463-020-00423-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voinsky I., Baristaite G., Gurwitz D. Effects of age and sex on recovery from COVID-19: Analysis of 5769 Israeli patients. J Infect. 2020;81(2):e102–e103. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wambier C.G., Goren A. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection is likely to be androgen mediated. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(1):308–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guan W.J., Liang W.H., Zhao Y. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with COVID-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(5) doi: 10.1183/13993003.00547-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vroegop A.V., Eeckels A.S., Van Rompaey V. COVID-19 and olfactory dysfunction - an ENT perspective to the current COVID-19 pandemic. B-ENT. 2020;16(1):81–85. https://www.europeanrhinologicsociety.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.Isidori A.M., Arnaldi G., Boscaro M., Falorni A., Giordano R. COVID-19 infection and glucocorticoids: update from the Italian Society of Endocrinology Expert Opinion on steroid replacement in adrenal insufficiency. J Endocrinol Invest. April 2020 doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01266-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bousquet J., Akdis C., Jutel M. Intranasal corticosteroids in allergic rhinitis in COVID-19 infected patients: An ARIA-EAACI statement [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 31] Allergy. 2020 doi: 10.1111/all.14302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walker A., Pottinger G., Scott A., Hopkins C. Anosmia and loss of smell in the era of covid-19. BMJ. 2020;370 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.