Abstract

Aims:

Clear cell papillary cystadenoma (CCPC) is associated with von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHLD), but rarely involves mesosalpinx and broad ligament (M/BL). This study provides new data about its behaviour and immunophenotype.

Methods and results:

We performed an analysis of four benign cases of CCPC of M/BL with either characteristic clinical features or genetic markers [loss of heterozygosity (LOH)] of VHLD in patients ranging from 24 to 36 years and a sporadic case in a 52-year-old presenting with peritoneal metastases. All CCPCs were papillary but had solid and tubular areas. Haemorrhage, thrombosis and scarring were constant features and related to an unusual pattern of subepithelial vascularity. All clear or oxyphilic cells coexpressed cytokeratin 7 (CK7), CAM5.2 and vimentin, with strong apical CD10 and nuclear paired box gene 2 (PAX2) immunoreactivity. Three cases also showed positivity for VHL40, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), Wilms’ tumour suppressor gene (WT-1) and cancer antigen 125 (CA125) but only one expressed renal cell carcinoma (RCC) antigen. Vascular plexus overexpressed nuclear and cytoplasmic WT-1.

Conclusion:

The VHLD-associated cases appeared to be benign, but the sporadic case exhibited a low malignant potential. CCPCs show histological and immunophenotypical similarities with the recently reported clear cell papillary RCC, although the previously unreported apical CD10 and nuclear PAX2 expression may be related to their mesonephric origin. CCPC has a distinctive sub-epithelial vascular pattern that is consistent with its pathogenesis.

Keywords: clear cell papillary cystadenoma, clear cell papillary renal cell carcinoma, mesonephric rests, mesosalpinx, sporadic, von Hippel-Lindau disease

Introduction

von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHLD) is a rare inherited autosomal dominant disorder which determines the presence of various types of neoplasms in different organs.1 These associated tumours are found only very rarely in the female genital tract, where they originate from mesonephric remnants2 and, therefore, occur in the mesosalpinx and broad ligament, being the counterparts of the more frequent epididymal neoplasm. Histologically, they usually correspond to clear cell papillary cystoadenomas (CCPC),2–7 although a case of endometrioid cystadenofibroma (ECAF) of the broad ligament has also been reported in association with VHLD.6 These tumours usually have a characteristic morphology when associated with VHLD, although rare sporadic cases have been reported.7

Until now, six of the eight documented cases of CCPC and ECAF reported in the female genital tract were published as single case reports,2–5,7,8 and the remaining two were included in a paper analysing the CCPC immunophenotype in its differential diagnosis with metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (CC-RCC).7

In this paper we describe tumours of mesosalpinx and broad ligament in five patients. Of these, four had either stigmata or genetic markers characteristic of VHLD. However, CCPC and ECAF occurred coincidentally in the fifth patient, who showed no evidence of VHLD.

In this paper, we review and update clinicopathological and immunophenotypical features of CCPC, including the analysis of new markers, emphasizing the differences in results from previous findings.7 We report for the first time a sporadic case of CCPC of the mesosalpinx associated with peritoneal metastases.

Materials and methods

Six tumours of mesosalpinx and broad ligament corresponding to five patients were found in the consultation files of one of the authors (F.F.N.). Clinical and follow-up data were available in all but case 4, which was lost to follow-up. The number of paraffin blocks ranged from eight in case 1 to one in case 3, with an average of four. Frozen section material was also available in case 1.

Immunohistochemistry was performed according to a standard procedure using the antibodies shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Antibodies used in this study

| Antibody | Clone | Vendor |

|---|---|---|

| CK7 | OV-TL 12/30 | DAKO, Glostrup, DK |

| CAM5.2 | CAM 5.2 | Master, Granada, ES |

| Vimentin | V9 | DAKO, Glostrup, DK |

| CD10 | 56C6 | DAKO, Glostrup, DK |

| PAX2 | Z-RX2 | Invitrogen, Camarillo,CA, USA |

| VHL40 | SC-135657 | Santa Cruz, Paso Robles, CA, USA |

| EMA | E29 | DAKO, Glostrup, DK |

| CA125 | OV185:1 | Master, Granada, ES |

| WT-1 | 6F-H2 | DAKO, Glostrup, DK |

| CD56 | 123C3 | DAKO, Glostrup, DK |

| Androgen R | AR441 | Master, Granada, ES |

| HBME-1 | HBME-1 | DAKO, Glostrup, DK |

| RCC | SPM314 | DAKO, Glostrup, DK |

| Calretinin | DAK-calret1 | DAKO, Glostrup, DK |

| α-oestrogen R | SP1 | DAKO, Glostrup, DK |

| Progesterone R | PgR636 | DAKO, Glostrup, DK |

| CD31 | JC70A | DAKO, Glostrup, DK |

R, Receptor.

For loss of heterozygosity (LOH) analysis, 5 μm sections were prepared from routinely processed tissue fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections were taken from the papillary tumours as well as normal adjacent tissue and were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in graded ethanols and lightly stained with haematoxylin and eosin. They were subsequently placed into 10% glycerol solution for at least 1 min [10 mm Tris, 0.1 mm ethylenediamine tetracetic acid (EDTA), pH 8.0, 10% glycerol].

Tumour cells were microdissected under direct light microscopic visualization using a 30-gauge, ½-inch needle attached to a tuberculin syringe. Adjacent non-neoplastic cells were also dissected for comparison. The microdissected cells were placed in a 20-μl proteinase K (DNA extraction) solution [0.1 mg/ml proteinase K (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) in 50 mm Tris-HCl, 1.0 mm EDTA (pH 8.0), 0.5% Tween 20] and incubated overnight at 37°C. The proteinase K was inactivated by incubation at 95°C for 5 min; 1.5 μl of this suspension was used in polymerase chain reactions (PCRs).

Five polymorphic marker regions were evaluated by PCR (Research Genetics, Inc., Huntsville, AL, USA): D3S1038, D3S1597, D3S1317, D3S1560 and D3S1110. Amplification was performed in a Perkin Elmer DNA thermocycler 480 (Foster City, CA, USA). PCR was performed in a 10-μl volume containing 1.5 μl DNA extraction solution, PCR buffer [10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mm KCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 0.01% w/v gelatin], 0.1–0.5 μm primers (forward and reverse), 200 μm each of dCTP, dGTP, dTTP and dATP, 2 μCi (32P) dCTP (6000 Ci/mm) and 0.1 unit AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Perkin Elmer).

Results

LOH OF VHLD GENE

Loss of heterozygosity at VHLD gene locus microsatellite markers was detected in cases 3, 4 and 5. Case 3 was positive for the four markers used in this study, while case four was positive for two and case 5 for only one. In case 2, poor fixation precluded successful demonstration of markers. Case 1 showed no loss of markers.

CLINICAL FINDINGS

The age of patients ranged from 24 to 52 years and except case 1 were all of reproductive age. Other VHLD-related tumours of various organs occurred in cases 2 and 5 (Table 2). However, case 3 displayed four LOH markers of VHLD, but showed neither symptoms nor any associated tumours, the adnexal mass being an incidental finding. In case 4, no history of symptoms was available, but tissue showed two LOH markers. Conversely, case 2 had a classical VHLD phenotype, but demonstration of LOH markers failed most likely due to suboptimal tissue preservation. Additional clinical data included polycystic ovarian disease in case 4. In summary, VHLD was diagnosed in cases 2–5 either by genetic studies or characteristic clinical data.

Table 2.

Clinicopathological, histological and genetic review of female genital tract tumours of von Hippel Lindau disease

| Source | Age | Site | Side & Size | Histology | LOH | VHL disease | Other | Treatment & behaviour |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gersell & King2 | 46 | MS | Lt 3 cm | CCPC | D3S1110, D3S10387 | ReA, Cy (R-L-P), RA | – | LSO, benign |

| Funk & Heiken3 | 46 | BL | Lt 3 cm | CCPC | Not analyzed | RCC, Cy (R-L-P) | Rt ovarian Cyst | LSO, benign |

| Korn et al.4 | 35 | BL | Rt 5, Lt 2 cm | CCPC | Not analyzed | He (C).RCC, Cy (R-P) | – | TC, benign |

| Gaffey et al.5 | 20 | PU | Rt 4 cm | CCPC | Not analyzed | RCC, He (C), Cy (R-P), MET | MET was locally invasive | TC, benign |

| Werness & Guccion6 | 38 | BL | Lt 8 cm | ECAF | D3S1110, 104/1057 | RA, Cy (R-L-P), He (C), Phaeocromocytoma | – | LSO Postop death |

| Aydin et al.7 | 32 | MS | UL/NA | CCPC | Not analyzed | RCC | – | USO, Recurrence, |

| Case 1 | 5 years | |||||||

| Aydin et al.7 Case 2 | NA | MS | UL/NA | CCPC | Not analyzed | Absent | – | USO, benign |

| Zanotelli et al.8 | 23 | MS | Rt 3.5, Lt 0.8 cm | CCPC | Not analyzed | He (Im) | – | BSO, benign |

| Present series Case 1a | 52 | MS & OI | Lt 6, Omental implants 3–2 cm | CCPC | No Loss | Absent | Benign omental implants | TAH-BSO, plus omentectomy A&W 15 yrs |

| Present series Case 1b | 52 | MS | Lt 4 cm | ECAF | No Loss | Absent | – | TAH-BSO, A&W 15 years |

| Present series Case 2 | 35 | BL | UL 3.5 cm | CCPC | Bad data | Massive Cy (R), He (C-Im) | Renal transplant | TC, A&W 7 years |

| Present series Case 3 | 34 | MS | Rt 5.5 cm | CCPC | D3S1110, D3S1038 D3S1317, D3S1597 | Absent | Term pregnancy | RSO, A&W 3 years |

| Present series Case 4 | 24 | MS | Lt 5 cm | CCPC | D3S1038, D3S1597 | NA | PCOD | BSO, LFU |

| Present series Case 5 | 36 | MS | Rt 5.2, Lt 3 cm | CCPC | D3S1560 | Familial VHL. Patient: ReA, RCC, Cy (R-L-P), He (C) | Grandmother, mother and sister died of VHLD-related complications | BSO, A&W 1 year |

Site: MS, Mesosalpinx; BL, broad ligament, PU, Parauterine; OI, Omental implant. Side and Size: UL, unilateral, NA, not available. Histology: CCPC, clear cell papillary cystadenoma; ECAF, endometrioid cystadenofibroma of the broad ligament. Von Hippel Lindau disease: ReA, Retinal angioma; Cy, cysts; R, renal; L, liver; P, pancreas; RA, renal adenoma; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; He, hemangioblastoma; C, cerebellar and (Im) intramedullary; MET, middle ear tumour. Other lesions: PCOD, polycystic ovarian disease. Treatment and behaviour: TC, tumourectomy; USO, unspecified salpingoophorectomy; LSO/RSO, left or right salpingo-oophorectomy; TAH-BSO, total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; A&W, alive and well; LFU, lost to follow-up.

In cases 3 and 4, the tumours were incidental findings during caesarean section and a bilateral ovarian wedge resection procedure for polycystic ovarian disease, respectively. In cases 2 and 5 they were identified, respectively, during diagnostic screening for tumours in VHLD. Only in case 1 did primary symptoms of abdomino-pelvic mass exist. Simple resection was performed in case 2, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) was performed in cases 4 and 5 and a unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in case 3. Total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) with BSO and omentectomy was carried out in case 1.

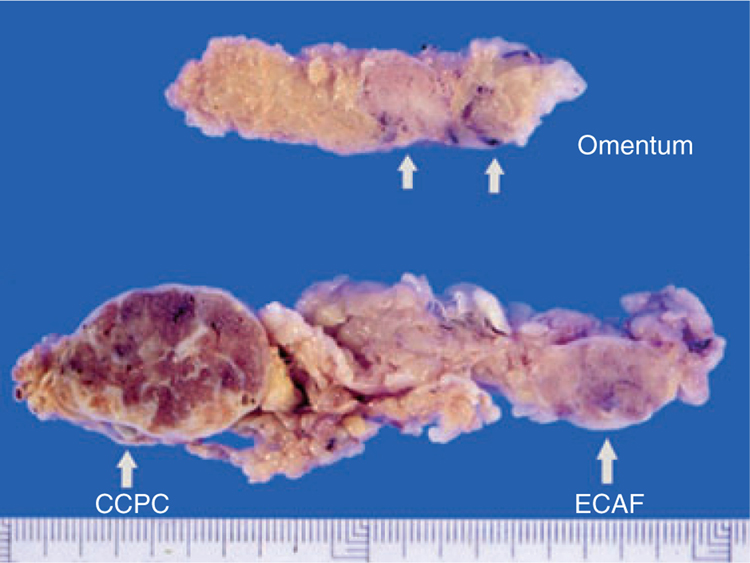

The clinical history of case 1 warrants further description. This previously healthy, obese 52-year-old patient presented with a painful left adnexal mass. On surgical examination, two distinct paraovarian masses were found: the larger mass measured 6 cm and was solid and tan in colour, while the other measured 4 cm and was white and fibrous (Figure 1). Further inspection revealed two 2–3-cm nodular, brown lesions in the omentum. By frozen section, the paraovarian mass was reported as a serous tumour, but the omental metastases were considered to be malignant. TAH, BSO, omentectomy and lymph node dissection were performed subsequently. No distant metastases or VHLD-associated lesions were detected. The patient is alive and well 15 years later without further treatment.

Figure 1.

Two nodular formations corresponding to clear cell papillary cystadenoma (CCPC) and endometrioid cystadenofibroma (ECAF) are present in the mesosalpinx of the obese patient of case 1. Note the brown, scarred appearance of CCPC. In the omentum (above) two nodular metastases are present.

PATHOLOGY

All of the papillary tumours with the exception of that in case 5 were unilateral, ranging from 3 to 6 cm in maximum diameter, with an average of 4.5 cm. Macroscopically, all tumours had a thickened fibrous capsule, often with adhesions, and were seen on cut section to be partly cystic, lobulated and tan in colour, with solid areas with haemorrhagic foci and broad or stellate fibrous scars (Figure 1).

Microscopically, all patients had tumours consistent with a diagnosis of CCPC. Additionally, the patient in case 1 had an associated ECAF (Figure 2A). Mesonephric tubules with prominent smooth muscle cuffs were seen in the peripheral areas of tumours in cases 1, 3 and 4 (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Cystadenofibroma with blunt papillae with endometrioid lining (A). Cystic tubulopapillary tumour from case 3 showing association with peripheral mesonephric rests (arrow) (B).

Cystic tumours contained complex tubulopapillary structures that ranged from broad to finely branching tracts. Their cores were often hyalinized containing old haemorrhagic foci with haemosiderin-laden macrophages (Figure 3A–B). Osseous tissue was found in case 1. Cysts often contained abundant cholesterol clefts or a dense hyaline material (Figure 3A). The papillae and tubules were lined by a uniform cuboidal epithelium which had round, centrally placed nuclei and a clear or eosinophillic cytoplasm (Figure 3B–C). No mitoses or atypia were seen in any case. In cases 1 and 3, the papillary architecture was partially effaced and clear cells were arranged in a solid pattern (Figure 3D) with occasional tubular formation (Figure 3E). The peritoneal metastases of case 1 were superficial and had a tubulopapillary architecture and bland cellularity (Figure 3F).

Figure 3.

Low magnification of tumour in case 2 (A) shows thick fronds with fine papillary component, broad areas of fibrosis and abundant cholesterol clefts. Papillary, clear cell component with fibrosis (B). Papillae may also show cuboidal eosinophilic epithelial lining and a rich vascular plexus (C). Prominent solid (D) and tubular (E) patterns can be seen. Omental metastasis from case 1 (F).

In all cases, subepithelial tumour vessels were prominent, some arterioles showing different stages of thrombotic occlusion.

Clinicopathological and genetical findings are summarized in Table 2.

IMMUNOHISTOCHEMISTRY

The clear or eosinophilic cuboidal epithelium diffusely coexpressed vimentin, cytokeratin 7 (CK7) and was positive with the monoclonal antibody CAM5.2. Nuclear paired box gene 2 (PAX2) (Figure 4A) and apical CD10 immunoreactivity (Figure 4B) was present in all cases. Three of five cases showed membranous staining for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) (Figure 4C), CA125, CD56, VHL40 (Figure 4D) and nuclear localization for Wilms’ tumour suppressor gene (WT-1). HMBE1 and androgen receptors were positive in two cases. Both calretinin and RCC showed focal isolated staining in one case each. All cases were negative for α-inhibin, oestrogen and progesterone receptors. Relevant results are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 4.

Selected immunophenotypical features: nuclear positivity for paired box gene 2 (PAX2) (A), strongapical free surface membranous positivity for CD10 (B) and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) (C). von Hippel-Lindau (VHL)40 (D) delineates epithelial membranes. Marked subepithelial vascularity is highlighted by both CD31 (E) and by positivity of Wilms’ tumour suppressor gene (WT-1) in both capillary nuclei and cytoplasms (F).

Table 3.

Immunophenotype of clear cell papillary cystadenoma of mesosalpinx and broad ligament

| Antibodies | Case 1a* | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK7 | + | + | + | + | + | 5/5 |

| Cam5.2 | + | + | + | + | + | 5/5 |

| Vimentin | + | + | + | + | + | 5/5 |

| CD10 | + | + | + | + | + | 5/5 |

| PAX2 | + | + | + | + | + | 5/5 |

| VHL40 | + | + | − | − | + | 3/5 |

| EMA | − | − | + | + | + | 3/5 |

| CA125 | + | + | + | − | − | 3/5 |

| WT-1 | + | + | − | − | + | 3/5 |

| AR | − | − | + | − | + | 2/5 |

| HBME-1 | + | + | − | − | − | 2/5 |

| Calretinin | + | − | − | − | − | 1/5 |

| RCC | − | − | + | − | − | 1/5 |

AR, Androgen receptor.

Similar results for both primary and implants.

A striking feature common to all cases was the presence of an extensive subepithelial capillary network, which was immunohistochemically highlighted by both membranous CD31 (Figure 4E) and strong WT-1 cytoplasmic and nuclear positivities (Figure 4F).

Discussion

Mutations of the VHL tumour suppressor gene determine loss of VHL protein function, which is related to high levels of expression and activity of hypoxia-inducible factors 1α and 2α,9,10 leading to an overproduction of angiogenic factors. These cause a complex vascularity, which is responsible for the frequent phenomena of haemorrhage, thrombosis, scarring and haemosiderin pigmentation which are common to all VHLD tumours including CCPC, as exemplified by all our cases. We were able to demonstrate an unusual vascular pattern consisting of a dense subepithelial plexus which was markedly highlighted when stained for WT-1: our antibody stained not only the endothelial cell nuclei, but also their cytoplasm. Cytoplasmic WT-1 staining is a phenomenon of unknown significance that has been reported as non-artefactual in some tumours.11 This sub-epithelial vascular pattern and atypical WT-1 positivity were constant and helps to differentiate CCPC from other papillary tumours of this area.

von Hippel-Lindau disease is associated with the presence of a wide variety of tumours in various organs. However, involvement of the reproductive tract is unusual; the epidydimis12 is affected more frequently than the broad ligament or the mesosalpinx and CCPC is the neoplasm characteristically found, originating from mesonephric structures, such as the epididymis in males and vestigial rests in females.5 A close relationship between CCPC and mesonephric (Wolffian) rests was confirmed in three of our cases. Another tumour type, ECAF of the broad ligament, has also been described in association with VHLD.6 Curiously, one of our cases showed the simultaneous occurrence of both tumours. Furthermore, two cases of ovarian steroid cell tumour associated with VHLD have also been reported.13

All but one6 of the seven previously reported instances of CCPC in the female have been associated with VHLD.2–5,7,8 Comparatively, in the males, only one-third12 of cases of CCPC involving the epididymis were found in association with the disease, the rest being apparently sporadic. These data should be considered carefully, as in many cases there may not have been either adequate follow-up or clinical investigations leading to demonstration of VHLD and eventual development of other neoplasms at a later age. Four of our cases had either characteristic VHL genetic markers or stigmata of the disease. Case 1 had neither, and no tumours in other organs were detected. Case 3 is of particular interest, as here CCPC was an incidental finding during a caesarean section, prompting genetic investigation of VHLD which was corroborated by the presence of four LOH markers of the disease. It is known that pregnancy accelerates VHLD lesions.14 Case 4 had genetic markers, but clinical data of VHLD were not provided. Case 5 had one LOH marker, a fully expressed disease and a family history involving the grandmother, mother and sister.

Low-grade malignant behaviour of CCPC with peritoneal metastases occurred only in a patient lacking both VHLD symptoms and LOH markers of VHLD. No further metastases were found during a long follow-up of 15 years. This is the first reported case in the female genital tract with this aggressive course. Its clinicopathological profile, showing unilateral involvement, larger size, low-grade malignancy and occurrence in an older patient, contrasts with that found in VHLD patients, where there is occasional bilateral involvement, small tumour size, benign behaviour and occurrence at an earlier age. A similar distribution between sporadic and syndrome-associated tumours can be seen in ovarian and testicular tumours associated with the Peutz Jegher syndrome15 or Carney’s complex:16 tumours associated with the syndromes are bilateral, small and usually benign, while unilateral, large, malignant tumours are of sporadic type.

Clear cell papillary cystadenomas very rarely display aggressive behaviour. There are only two such reports, one in the epididymis of a 82-year-old patient17 and the other in the mesosalpinx of a 32-year-old female, which recurred 5 years after salpingectomy. Neither of these patients was known to have VHLD.7

Similar low-grade malignant behaviour is present in the recently described clear cell tubulopapillary renal cell carcinoma (CCTP-RCC),18,19 a tumour which has a similar histology, with bland clear cells arranged in a cystic, tubuloacinar and papillary architecture19,20 as well as an association with VHLD.19,20 These common features would make the differential diagnosis of CCPC with metastatic CCTP-RCC particularly difficult on morphology alone, as CCPC can also contain acinic or solid areas or tubular formations with dense colloid contents. This occurred in two of our cases, one of them associated with peritoneal metastases. However, the correct diagnosis is facilitated by its location in the mesosalpinx or broad ligament, a rare site for metastases, and its frequent association with mesonephric rests.

Immunophenotype has been analysed especially in order to differentiate it from metastatic CC-RCC. Aydin et al.7 showed that CCPC of both epididymis and mesosalpinx were positive for EMA and CK7, but negative for RCC antigen. Only one of their five cases was positive for CD10. This immunophenotype contrasted with the usual profile of CC-RCC, which is usually negative for CK7 and positive for RCC antigen, vimentin and CD10.21 These differences proved helpful in ruling out metastatatic CC-RCC.7

The present study has analysed a higher number of CCPC cases in the female and with a more extensive antibody panel, including PAX2, VHL40 and WT-1, than previous studies.7,12,22 While our results confirm the conspicuous co-expression of CK7 and vimentin,22 they differ from earlier reports, as all our cases showed a strong apical positivity for CD10 and one was positive for the RCC antigen. CD10 has been reported as negative in all reports but one of CCPC.7 In our cases, CD10 shows similar apical positivity to the one found in the mesonephric rests of mesosalpinx and cervix,23 which seems to be the structure from which CCPC are derived. Apical positivity differs from the cytoplasmic positivity of CC-RCC but is, however, similar to that occurring in the usual type of papillary RCC.21

Clear cell tubulopapillary renal cell carcinoma and CCPC exhibit not only histological similarities, but also share some immunohistochemical features such as co-expression of CK7 and vimentin as well as negativity for the RCC antigen.24 The latter, however, was positive in only one of our cases as well as in a previous case occurring in the epidydimis.12 Furthermore, it should be borne in mind that six of 36 cases studied by Aydin et al.19 were positive for CD10.

Paired box gene 2, a nuclear transcription factor, is present in Müllerian-derived organs and lymphoid cells and represents a good marker for renal tumours.21 PAX2 is also constantly expressed by mesonephric remnants,25 which would be also consistent with the presumed mesonephric origin of CCPC.

VHL40,26 a monoclonal antibody against Elongin III (SIII), a functional target of the VHL protein, was strongly positive in tumour cells but is non-specific, as it is also broadly expressed in many tissues,26 including the nearby fallopian tube (FFN, PG) (personal observation).

WT-1, EMA and CA125 immunostaining showed marked positivity in three of five tumours, and therefore their immunophenotype does not differentiate them from serous papillary lesions. This may prove problematic, as the latter should be included in the differential diagnosis, especially in frozen section. Indeed, it led to an incorrect diagnosis initially in one of our cases and in a previously published case.7 However, the differential diagnosis is straightforward on paraffin-embedded material, due to the overall tubulopapillary architecture, rather than the finely branching papillae and characteristic bland clear cells and vascularity seen in CPCC. Both ovarian clear cell carcinomas and CPCC have a clear cytoplasm and hyalinized stroma, but the former show marked atypicality, different vascular pattern and immunophenotype.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Drs Eladio Mendoza (Seville, Spain) and Manuel Moreira (San José, Costa Rica) for their help in the preparation of this paper.

Abbreviations:

- BSO

bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

- CCPC

clear cell papillary cystadenoma

- CK7

cytokeratin 7

- ECAF

endometrioid cystadenofibroma

- EMA

epithelial membrane antigen

- LOH

loss of heterozygosity

- M/BL

mesosalpinx and broad ligament

- PAX2

paired box gene 2

- RCC

renal cell carcinoma

- TSH

total abdominal hysterectomy

- VHLD

von Hippel-Lindau disease

References

- 1.Maher ER, Neumann HP, Richard S. von Hippel-Lindau disease: a clinical and scientific review. Eur. J. Hum. Genet 2011; 19; 617–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gersell DJ, King TC. Papillary cystadenoma of the mesosalpinx in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Am. J. Surg. Pathol 1988; 12; 145–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Funk KC, Heiken JP. Papillary cystadenoma of the broad ligament in a patient with von Hippel-Lindau disease. Am. J. Roentgenol 1989; 153; 527–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korn WT, Schatzki SC, DiSciullo AJ et al. Papillary cystadenoma of the broad ligament in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 1990; 163; 596–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaffey MJ, Mills SE, Boyd JC. Aggressive papillary tumor of middle ear/temporal bone and adnexal papillary cystadenoma. Manifestations of von Hippel-Lindau disease. Am. J. Surg. Pathol 1994; 18; 1254–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Werness BA, Guccion JG. Tumor of the broad ligament in von Hippel-Lindau disease of probable mullerian origin. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol 1997; 16; 282–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aydin H, Young RH, Ronnett BM et al. Clear cell papillary cystadenoma of the epididymis and mesosalpinx: immunohistochemical differentiation from metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol 2005; 29; 520–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zanotelli DB, Bruder E, Wight E et al. Bilateral papillary cystadenoma of the mesosalpinx: a rare manifestation of Von Hippel-Lindau disease. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet 2010; 282; 343–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Paulsen N, Brychzy A, Fournier MC et al. Role of transforming growth factor-alpha in von Hippel-Lindau (VHL)(−/−) clear cell renal carcinoma cell proliferation: a possible mechanism coupling VHL tumor suppressor inactivation and tumorigenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 2001; 98; 1387–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frew IJ, Minola A, Georgiev S et al. Combined VHLH and PTEN mutation causes genital tract cystadenoma and squamous metaplasia. Mol. Cell. Biol 2008; 28; 4536–4548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bing Z, Pasha TL, Acs G et al. Cytoplasmic overexpression of WT-1 in gastrointestinal stromal tumor and other soft tissue tumors. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol 2008; 16; 316–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Odrzywolski KJ, Mukhopadhyay S. Papillary cystadenoma of the epididymis. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med 2010; 134; 630–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner M, Browne HN, Marston Linehan W et al. Lipid cell tumors in two women with von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Obstet. Gynecol 2010; 116(Suppl. 2); 535–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayden MG, Gephart R, Kalanithi P et al. Von Hippel-Lindau disease in pregnancy: a brief review. J. Clin. Neurosci 2009; 16; 611–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young RH, Welch WR, Dickersin GR et al. Ovarian sex cord tumor with annular tubules: review of 74 cases including 27 with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and four with adenoma malignum of the cervix. Cancer 1982; 50; 1384–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plata C, Algaba F, Andujar M et al. Large cell calcifying Sertoli cell tumour of the testis. Histopathology 1995; 26; 255–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurihara K, Oka A, Mannami M et al. Papillary adenocarcinoma of the epididymis. Acta Pathol. Jpn 1993; 43; 440–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gobbo S, Eble JN, Grignon DJ et al. Clear cell papillary renal cell carcinoma: a distinct histopathologic and molecular genetic entity. Am. J. Surg. Pathol 2008; 32; 1239–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aydin H, Chen L, Cheng L et al. Clear cell tubulopapillary renal cell carcinoma: a study of 36 distinctive low-grade epithelial tumors of the kidney. Am. J. Surg. Pathol 2010; 34; 1608–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rohan SM, Xiao Y, Liang Y et al. Clear-cell papillary renal cell carcinoma: molecular and immunohistochemical analysis with emphasis on the von Hippel-Lindau gene and hypoxia-inducible factor pathway-related proteins. Mod. Pathol 2011; 24; 1207–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Truong LD, Shen SS. Immunohistochemical diagnosis of renal neoplasms. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med 2011; 135; 92–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilcrease MZ, Schmidt L, Zbar B et al. Somatic von Hippel-Lindau mutation in clear cell papillary cystadenoma of the epididymis. Hum. Pathol 1995; 26; 1341–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ordi J, Romagosa C, Tavassoli FA et al. CD10 expression in epithelial tissues and tumors of the gynecologic tract: a useful marker in the diagnosis of mesonephric, trophoblastic, and clear cell tumors. Am. J. Surg. Pathol 2003; 27; 178–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adam J, Couturier J, Molinie V et al. Clear-cell papillary renal cell carcinoma: 24 cases of a distinct low-grade renal tumour and a comparative genomic hybridization array study of seven cases. Histopathology 2011; 58; 1064–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rabban JT, McAlhany S, Lerwill MF et al. PAX2 distinguishes benign mesonephric and mullerian glandular lesions of the cervix from endocervical adenocarcinoma, including minimal deviation adenocarcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol 2010; 34; 137–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakashita N, Takeya M, Kishida T et al. Expression of von Hippel-Lindau protein in normal and pathological human tissues. Histochem. J 1999; 31; 133–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]