Abstract

This cross-sectional study examines the gender distribution of endowed chairs in departments of medicine and the association of gender with holding an endowed chair.

Although women are increasingly represented in academic medicine, gender inequities persist in senior positions. Endowed chairs are among the most distinguished roles in a university setting and typically provide funding that can support salary, novel research, or staff for the chair holder.1 Previous research has documented gender differences in compensation, funding, authorship, and leadership positions in medicine.2,3,4 To our knowledge, no prior studies have examined whether inequities exist in the allocation of endowed chairs within academic medicine. Thus, we examined the gender distribution of endowed chairs in departments of medicine and determined if gender is associated with holding an endowed chair after controlling for other relevant characteristics.

Methods

We considered departments of medicine from the top 10 schools of medicine based on National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding in 2018 (http://www.brimr.org/NIH_Awards/2018/NIH_Awards_2018.htm). Endowed chair and full professor lists were obtained directly from department chairs between November 2019 and January 2020 and subsequently coded using publicly available sources (eg, institutional websites, NIH Reporter, Scopus [Elsevier], and state licensing boards) for gender, graduate degree, years since completion of graduate degree, subspecialty, publication and citation number, H-index, and total NIH grant funding as a principal investigator. Because no identifiable private information was included about the individual members of the organizations who were the participants in the research, the research plan was filed with the University of Michigan institutional review board, which did not consider it to require regulation or informed consent.

After describing full professors with and without endowed chairs by gender, we constructed a multivariable logistic regression model to determine whether gender was independently associated with holding an endowed chair after controlling for other measured characteristics. Given the collinearity of publication number, citations, and H-index, we retained citations as the sole measure of publication productivity in the model after considering the Akaike Information Criterion for model selection. Analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute), and statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Results

Of the 1654 full professors in the sample, 411 (25%) held endowed chairs (of whom 76 [18.5%] were women). On bivariable analysis, full professors with vs without endowed chairs differed significantly for all measured characteristics, as did men vs women full professors (Table).

Table. Characteristics of Male and Female Full Professors With and Without Endowed Chairs at Top 10 US Medical Schoolsa.

| Characteristic | Full professors (N = 1654), No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women (n = 461) | Men (n = 1193) | |||

| With endowed chairs (n = 76 [16.5%]) | Without endowed chairs (n = 385 [83.5%]) | With endowed chairs (n = 335 [28.1%]) | Without endowed chairs (n = 858 [71.9%]) | |

| Subspecialty | ||||

| Cardiology | 7 (14.9) | 40 (85.1) | 67 (26.2) | 189 (73.8) |

| Endocrinology, metabolism, and diabetes | 9 (23.7) | 29 (76.3) | 27 (38.0) | 44 (62.0) |

| Gastroenterology and hepatology | 6 (17.1) | 29 (82.9) | 29 (27.6) | 76 (72.4) |

| General internal medicine and hospital medicine | 9 (9.8) | 83 (90.2) | 31 (22.6) | 106 (77.4) |

| Geriatrics and palliative medicine | 3 (10.0) | 27 (90.0) | 10 (26.3) | 28 (73.7) |

| Hematology and oncology | 13 (23.6) | 42 (76.4) | 58 (33.7) | 114 (66.3) |

| Infectious diseases | 6 (12.2) | 43 (87.8) | 21 (20.0) | 84 (80.0) |

| Nephrology/kidney | 1 (4.5) | 21 (95.5) | 27 (31.8) | 58 (68.2) |

| Other | 4 (12.9) | 27 (87.1) | 18 (39.1) | 28 (60.9) |

| Pulmonary and critical care | 10 (30.3) | 23 (69.7) | 23 (20.4) | 90 (79.6) |

| Rheumatology/allergy/immunology | 8 (27.6) | 21 (72.4) | 24 (36.9) | 41 (63.1) |

| Degree | ||||

| MD or equivalent | 58 (16.2) | 299 (83.8) | 265 (27.7) | 690 (72.3) |

| MD and other doctorate | 11 (30.6) | 25 (69.4) | 54 (36.2) | 95 (63.8) |

| Doctorate, non-MD, or equivalent | 7 (10.4) | 60 (89.6) | 15 (17.6) | 70 (82.4) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) |

| NIH grant funding level as a PI, millions, $b | ||||

| 1-<2.5 | 9 (13.4) | 58 (86.6) | 36 (18.4) | 160 (81.6) |

| 2.5-<8.0 | 16 (18.0) | 73 (82.0) | 44 (23.2) | 146 (76.8) |

| 8.0-<20.0 | 22 (26.5) | 61 (73.5) | 63 (33.0) | 128 (67.0) |

| ≥20.0 | 23 (44.2) | 29 (55.8) | 135 (59.0) | 94 (41.0) |

| Not applicable/none reported | 6 (3.5) | 164 (96.5) | 57 (14.7) | 330 (85.3) |

| Total publicationsc | ||||

| Not available | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) |

| 0-60 | 9 (6.4) | 131 (93.6) | 29 (12.6) | 202 (87.4) |

| 61-120 | 23 (17.2) | 111 (82.8) | 60 (20.4) | 234 (79.6) |

| 121-210 | 23 (19.5) | 95 (80.5) | 92 (30.5) | 210 (69.5) |

| ≥211 | 21 (31.3) | 46 (68.7) | 153 (42.3) | 209 (57.7) |

| Total citationsc | ||||

| Not available | 0 (0) | 12 (100) | 1 (6.7) | 14 (92.3) |

| 0-2400 | 11 (7.6) | 133 (92.4) | 32 (13.8) | 200 (86.2) |

| 2401-6300 | 21 (15.7) | 113 (84.3) | 47 (16.7) | 234 (83.3) |

| 6301-12 750 | 20 (19.0) | 85 (81.0) | 90 (28.8) | 223 (61.2) |

| ≥12 751 | 24 (36.4) | 42 (63.6) | 165 (46.9) | 187 (53.1) |

| H-indexc | ||||

| Not available | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) |

| 0-23 | 7 (4.6) | 145 (95.4) | 30 (12.2) | 215 (87.8) |

| 24-38 | 26 (18.3) | 116 (81.7) | 49 (17.6) | 229 (82.4) |

| 39-54 | 21 (22.6) | 72 (77.4) | 93 (28.9) | 229 (71.1) |

| ≥55 | 22 (30.6) | 50 (69.4) | 162 (47.1) | 182 (52.9) |

| Years since completion of graduate degree, mean (SD) [range] | ||||

| Continuous (+1 y) | 32.33 (8.84) [12.00-57.00] | 34.38 (9.33) [5.00-68.00] | 36.23 (9.01) [16.00-63.00] | 29.93 (7.84) [12.00-54.00] |

Abbreviations: NIH, National Institutes of Health; PI, principal investigator.

Schools were selected for being within the top 10 as ranked using the Blue Ridge Institute for Medical Research rankings (ranking tables of NIH funding to US medical schools in 2018; http://www.brimr.org/NIH_Awards/2018/NIH_Awards_2018.htm).

The NIH grant funding amount was based on all available fiscal years for each PI from NIH reporter (https://projectreporter.nih.gov/).

Total publications, citations, and H-index were determined using Scopus (Elsevier; https://www.scopus.com/freelookup/form/author.uri).

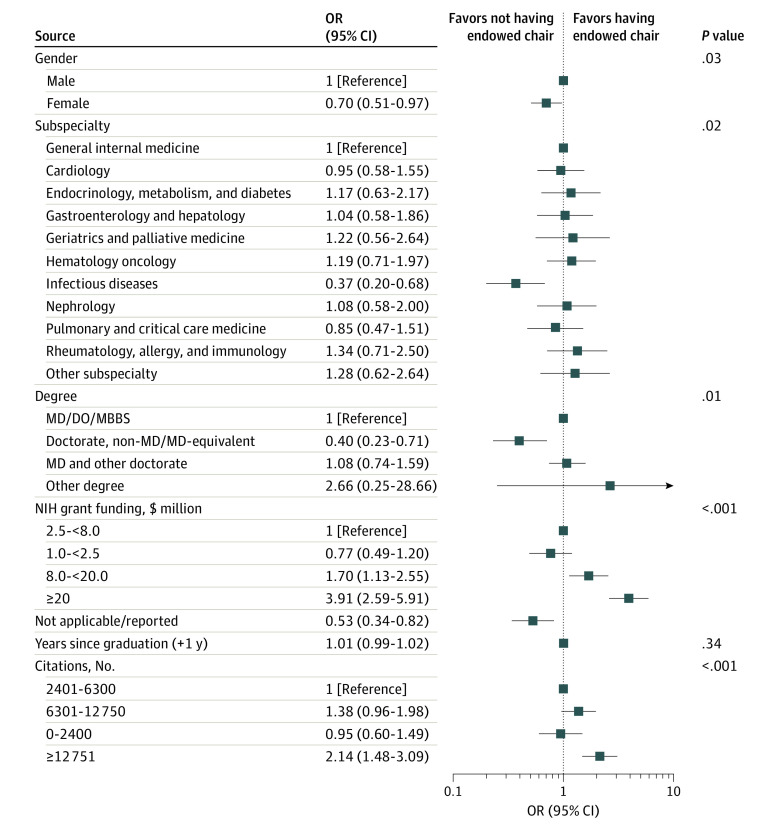

On multivariable analysis (Figure), factors independently associated with holding an endowed chair were specialty, having an MD, higher funding, higher citations, and male gender. Women full professors were significantly less likely to hold endowed chairs than men, even after adjustment for differences in specialty, degree, citations, funding, and graduation year (odds ratio [OR], 0.70; 95% CI, 0.51-0.97; P = .03). The magnitude of the gender difference was consistent when adding institution as a random effect (OR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.56-0.97; P = .03) or fixed effect (OR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.64-1.02; P = .07). We found no significant interactions between gender and the other model covariates.

Figure. Multivariable Logistic Regression Model Explaining Having an Endowed Chair for Full Professors.

The model includes 1598 individuals with complete data on covariates listed. NIH indicates National Institutes of Health; OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

Within top-tier US medicine departments, women full professors are less likely to hold endowed chairs than their male counterparts. Although endowed chairs are allocated, at least in part, on the basis of objective scholarly performance, this study observed persistent gender differences even after adjustment for such relevant factors. Other factors may affect the selection of endowed chairs. For example, women may be less likely to receive sponsorship from predominantly male faculty who interface with philanthropists, and women may feel less comfortable with philanthropic solicitation,5 potentially decreasing their chances of securing an endowed chair. Women faculty may also face gender-biased evaluations6 that require them to have greater professional achievements to be awarded an endowed chair.2

Study limitations include the inability to control for faculty track (eg, clinical vs tenure) or quality of medical/graduate school where professors received their degree. We did not have access to information on endowment amounts or include quasiendowments provided through state lines. Finally, we lacked information on race, ethnicity, sexuality, or other characteristics that may affect selection.

Nevertheless, the results of this study suggest the under-representation of women among endowed chairs compared with their male peers is unlikely to be because of differences in merit alone. Given the considerable prestige and resources that accompany endowed chairs, greater transparency in the allocation of these positions is necessary to understand and reduce gender inequities.

References

- 1.Treviño LJ, Gomez-Mejia LR, Balkin DB, Mixon FG Jr. Meritocracies or masculinities? the differential allocation of named professorships by gender in the academy. J Manage. 2018;44(3):972-1000. doi: 10.1177/0149206315599216 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mangurian C, Linos E, Urmimala S, Rodriguez C, Jagsi R What’s holding women in medicine back from leadership. Accessed March 1, 2020. https://hbr.org/2018/06/whats-holding-women-in-medicine-back-from-leadership?utm_source=twitter&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=hbr

- 3.Jagsi R, Means O, Lautenberger D, et al. Women’s representation among members and leaders of national medical specialty societies. Acad Med. 2020;95(7):1043-1049. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mensah M, Beeler W, Rotenstein L, et al. Sex differences in salaries of department chairs at public medical schools. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(5):789-792. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.7540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walter JK, Griffith KA, Jagsi R. Oncologists’ experiences and attitudes about their role in philanthropy and soliciting donations from grateful patients. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(32):3796-3801. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.6804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinpreis RE, Anders KA, Ritzke D. The impact of gender on the review of the curricula vitae of job applicants and tenure candidates: a national empirical study. Sex Roles. 1999;41(7-8):509-528. doi: 10.1023/A:1018839203698 [DOI] [Google Scholar]