Key Points

Question

How do US state drug product selection laws vary with regard to how pharmacists can substitute prescriptions for brand-name drugs with small-molecule generic drug or interchangeable biologic equivalents?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of all 50 states and Washington, DC, substantial variation was noted in generic substitution rules for small-molecule drugs, including whether substitution was mandatory or permissive, whether patient consent and notification were required before and after substitution, and whether pharmacists were protected from liability for substitution. Almost all states imposed heightened requirements for interchangeable biologic substitution.

Meaning

The findings of this study suggest a need for optimizing state drug product selection laws to improve medication adherence and reduce drug spending.

Abstract

Importance

Brand-name drugs, including biologics, have been the primary source of increasing prescription drug spending in the US. Each state has drug product selection laws that regulate whether and how pharmacists can substitute prescriptions for brand-name drugs with more affordable equivalents, either small-molecule generic drugs or interchangeable biologics, but the details of these laws can vary.

Objective

To examine the variation in state drug product selection laws with regard to factors that may affect which version of a drug is dispensed.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A cross-sectional analysis was performed, using a legal database, to obtain information on state laws of all states plus Washington, DC, as they existed on September 1, 2019.

Exposures

Whether substitution was mandatory or permissive, patient consent was needed prior to substitution, patient notification of substitution was required independent of the drug’s packaging, and/or pharmacists were protected from special risk of liability for substitution.

Main Outcomes and Measures

For small-molecule and biologic drugs, descriptive statistics were generated for the 4 exposure variables. In addition, for small-molecule drugs, a generic substitution score with a maximum of 1 point was assigned for each exposure variable (range, 0-4 points), with higher scores indicating regulatory requirements limiting substitution.

Results

This cross-sectional analysis of the generic drug substitution regulations in the 50 US states and Washington, DC, found that for small-molecule drugs, 19 states required pharmacists to perform generic substitution; 7 states and Washington, DC, required patient consent; 31 states and Washington, DC, mandated patient notification independent of the drug’s packaging, and 24 states did not explicitly protect pharmacists from greater liability. Nine states and Washington, DC, had a generic substitution score for small-molecule drugs of 3 or higher, and 45 states had more stringent requirements for interchangeable biologic substitution, most commonly mandatory physician notification.

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings of this study suggest that there is a need for optimizing state drug product selection laws to promote generic and interchangeable biologic substitution, which may help improve medication adherence and reduce drug spending.

This cohort study examines the varying policies on substitution of generic drugs for brand-name products throughout the US.

Introduction

The US spends more per capita on prescription drugs than any other country in the world.1 Brand-name drugs account for most of this spending, making up more than 70% of all prescription drug costs but only about 10% of prescriptions.2 Over the past 3 decades, the main counterweight to high brand-name drug spending has been small-molecule generic drugs, which emerge after the brand-name drug’s market exclusivity period and are designated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as being bioequivalent. Between 2007 and 2016, generic drugs saved the US health care system $1.7 trillion.3 Availability of low-cost generic drugs may also promote medication adherence among patients4 and lead to improved clinical outcomes.5,6,7

State laws are key to ensuring reductions in spending and improvements in adherence from generic drugs. In the US, pharmacy practices are managed at the state level, and each state has a set of drug product selection laws that regulate how pharmacists dispense drugs.8 The operation of drug product selection laws helps to determine the efficiency of the generic drug market. For example, when such laws allow pharmacists to automatically substitute a generic drug for its brand-name version, generic manufacturers are incentivized to earn market share by offering their products at as low a cost as possible and do not have to spend resources on marketing or other efforts to differentiate themselves from other manufacturers. This competition results in drug prices decreasing to close to the cost of production after a sufficient number of interchangeable generic drugs becomes available.9

However, state drug product selection laws can vary in important respects, such as whether the substitution is mandatory or permissive and whether patient consent is required. An investigation of Medicaid outpatient dispensing of simvastatin (Zocor) between 2006 and 2007 by Shrank et al10 found that states requiring patient consent had 25% lower generic substitution rates. By undermining efficient dispensing of generic drugs, such variation in state drug product selection laws lead to unnecessary use of expensive brand-name versions. The investigators estimated that eliminating the patient consent requirement would have led to more than $100 million in savings for just 3 medications—atorvastatin (Lipitor), clopidogrel (Plavix), and olanzapine (Zyprexa)—in the year following loss of market exclusivity.

Despite their widespread use, generic medications have remained underused in many clinical contexts, including cardiovascular disease management,11 combination products,12 and oral contraceptive medications.13 In addition, in the past decade, costly biologic drugs have become more common in the drug market. Today, biologics represent only 2% of dispensed medications but nearly 40% of spending.14 Biologic drugs had been excluded from generic-style competition until 2010, when the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act created a regulatory process for approving follow-on biologic drugs based on the generic drug approval system.15 Two types of approvals were authorized: biosimilars, which have no clinically meaningful differences in safety, purity, and potency to the originator biologic drug, and interchangeable biologics, which are biosimilar agents that have met additional testing standards demonstrating that they may be safely substituted for the originator biologic without the intervention of the prescribing physician.16 State laws do not allow pharmacist substitution of biosimilar drugs and vary with their approach to interchangeable biologic substitution.17 Although the FDA has yet to designate any biosimilar drugs as interchangeable,18 the first interchangeable biologics may appear soon, with the FDA having begun regulating insulin products as biologics as of March 2020.19 Efficient state drug product selection laws could then be critical to lowering spending on biologic drugs and ensuring optimal use of products, such as interchangeable insulin.20,21 We sought to understand the current landscape of drug product selection laws in the US, including how different states approach interchangeable biologic substitution.

Methods

We searched the legal database Westlaw Edge (Thomson Reuters)22 for all statutes and regulations in each state and Washington, DC, related to pharmacist dispensing of prescription medications between March 1 and March 30, 2019. We used the search terms drug, generic, biologic, biosimilar, follow-on biologic, product, selection, and substitution and reviewed neighboring sections of retrieved statutes and regulations using the database's table of contents tool to develop the range of each state's drug product selection laws. We reassessed the currency of these laws in October 2019, capturing any updates as of September 1, 2019.

Variable Extraction and Data Analysis

We instituted an iterative process to develop the scheme for data extraction. An investigator (A.S.) first reviewed drug product selection laws in 10 states to identify factors that may affect whether a brand-name or generic/interchangeable biologic version of a drug was dispensed. This review resulted in the identification of the following variables: (1) duty to substitute (whether substitution was mandated or permissive), (2) notification (whether patient notification of the substitution independent of the drug’s packaging was required), (3) consent (whether patient consent for the substitution was required, patient consent was not specifically required but refusal was explicitly allowed, or no such reference was made), and (4) liability (whether reference was made that pharmacists incurred no greater risk of liability for substitution than if the brand-name product were dispensed, specific mention was made of possibly increased liability, or no such reference was made). Two of us (C.A.S. and V.L.W.d.W.) then independently reviewed the laws in 50 states and Washington, DC, and extracted those variables as they applied to generic drugs and interchangeable biologics between April 1, 2019, and November 30, 2019. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Variation in these laws was documented using descriptive statistics. For small-molecule drugs, this included developing a generic substitution score for each state and Washington, DC, with a maximum of 1 point assigned for each variable that indicated a regulatory requirement making generic substitution more restrictive (Table 1). For variables with 2 options, a score of 0 or 1 was assigned. For variables with 3 possibilities, a score of 0, 0.5, or 1 was assigned. A lower total score indicates a state regulatory framework more favorable to generic substitution of small-molecule drugs. Differences between requirements for generic and interchangeable biologic substitution within each state were then examined. Institutional review board approval was not required because the study used only public data on state laws and not human participants.

Table 1. Generic Substitution Scoring Scheme for Small-Molecule Drugs.

| Variable | Pointsa |

|---|---|

| Duty to substitute | |

| Yes | 0 |

| No | 1 |

| Patient notification | |

| Not required independent of packaging | 0 |

| Required independent of packaging | 1 |

| Patient consent | |

| Not required | 0 |

| Opportunity for refusal noted | 0.5 |

| Required | 1 |

| Liability for substitution vs not substituting | |

| No greater risk | 0 |

| Not specified | 0.5 |

| Possibly greater risk | 1 |

| Total possible points | 4 |

Possible range of scores is 0 to 4 (with a maximum of 1 point for each of the 4 variables); lower scores reflect a regulatory framework more favorable to substitution.

Results

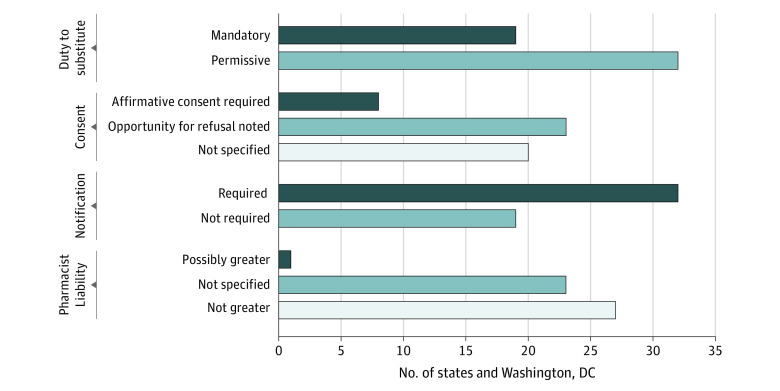

We found substantial variation in drug product selection laws (Figure 1). With regard to small-molecule drugs, less than half of the states (n = 19) mandated generic substitution by pharmacists when generic products were available (noting that pharmacists “shall” substitute). The remaining 31 states and Washington, DC, permitted but did not require substitution (noting that pharmacists “may” substitute); of these jurisdictions, 4 required pharmacies to post notice for patients of the possibility of substitution.

Figure 1. Variation in Generic Substitution Policies.

Variation in generic substitution policies for small-molecule generic drugs related to pharmacist duty to substitute, patient notification and consent, and pharmacist liability adopted by 50 states and Washington, DC.

Seven states and Washington, DC, required that patients consent to substitution, while 23 states noted a right of patients to refuse substitution without requiring that they consent. If substitution was performed, 31 states and Washington, DC, mandated that patients be notified of the action independent of the drug’s packaging.

Most states and Washington, DC (n = 27) explicitly protected pharmacists from greater liability for substitution. By contrast, 23 states did not, while 1 state (Connecticut) noted the possibility of increased liability (“Neither the failure to instruct by the purchaser...nor the fact that a sign has been posted...shall be a defense on the part of a pharmacist against a suit brought by any such purchaser”).23

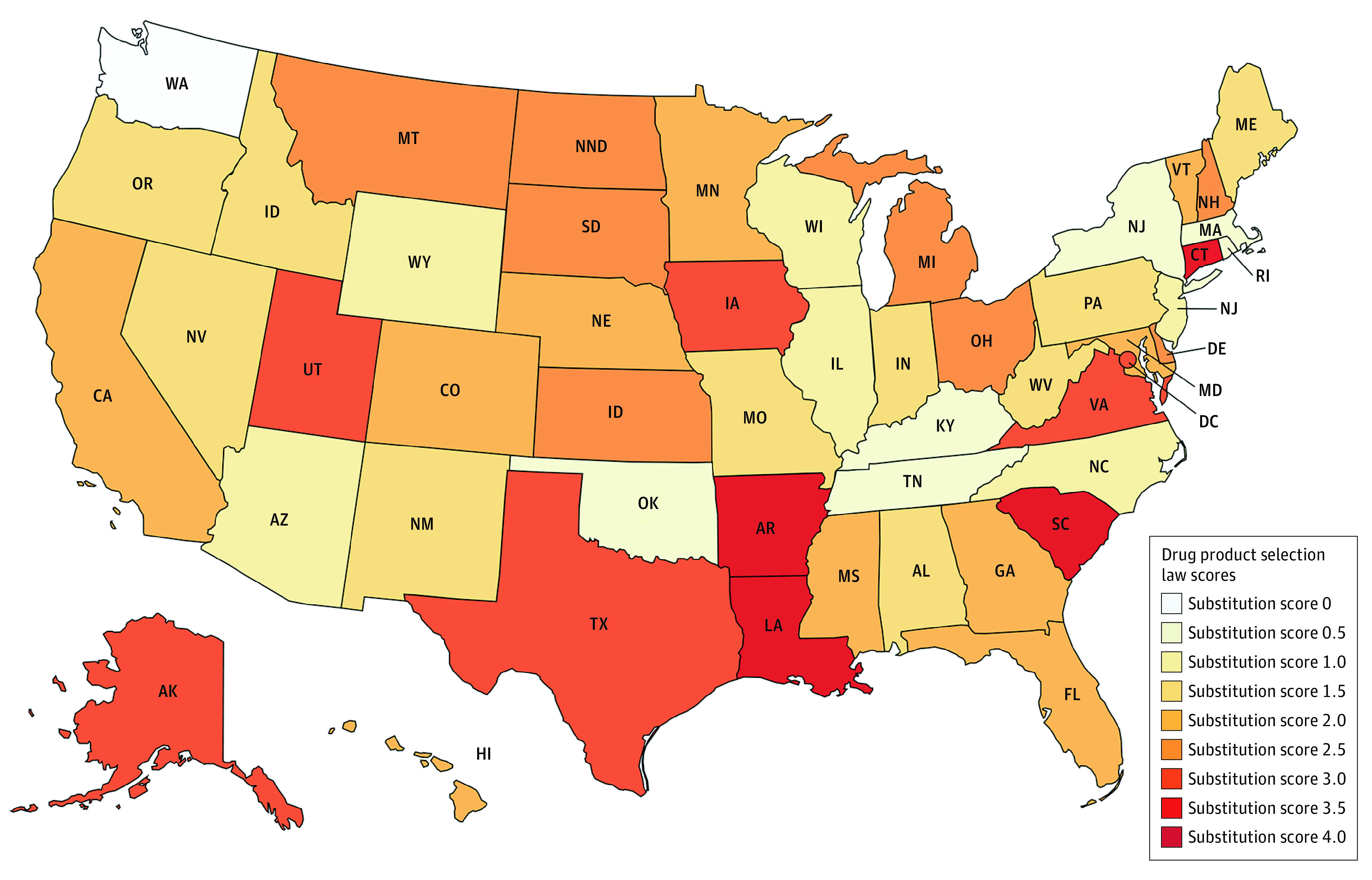

Figure 2 shows the generic substitution score assigned to each state and Washington, DC. Thirteen states (Arizona, Illinois, Kentucky, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Washington, Wisconsin, and Wyoming) had scores between 0 and 1, reflecting few restrictions for generic substitution of small-molecule drugs. By contrast, 9 states (Alaska, Arkansas, Connecticut, Iowa, Louisiana, South Carolina, Texas, Utah, and Virginia) and Washington, DC, had scores of 3 or higher, indicating greater barriers to generic substitution.

Figure 2. Heat Map of Generic Substitution Scores.

Heat map showing range of small-molecule generic drug substitution scores across all 50 states and Washington, DC. Possible range of scores is 0 to 4, with lower scores reflecting regulatory frameworks more favorable to substitution.

Ninety percent of the states (n = 45) had more stringent requirements for substitution of interchangeable biologics than for substitution of generic drugs (Table 2). The most common heightened requirement—enacted by 45 states—was a mandate that physicians be notified of substitution. For example, California stipulated that within 5 days of dispensing, the pharmacist must communicate the substitution through “an entry that can be electronically accessed by the prescriber.”24 Nine states (Alabama, Arizona, Illinois, Massachusetts, Missouri, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oregon, and Rhode Island) did not have patient notification requirements for generic substitution but did have them for interchangeable biologic substitution. Six states (Florida, Indiana, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee) that mandated generic drug substitution made interchangeable biologic substitution permissive.

Table 2. Variation in Policy Changes for Interchangeable Biologic Substitution Compared With Each State’s Generic Drug Substitution Policies.

| Policy change for interchangeable biologic vs generic substitution | States enacting the policy changea |

|---|---|

| Antisubstitution changes | |

| From mandatory to permissive substitution | Florida, Indiana, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Tennessee |

| From no patient notification to patient notification requirement | Alabama, Arizona, Illinois, Massachusetts, Missouri, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oregon, Rhode Island |

| From no physician notification to physician notification requirement | Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, Nevada, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming |

| Prosubstitution changes | |

| From no statement about liability for substitution to statement that pharmacists have no greater liability for substitution | New Jersey |

| Neutral changes | |

| From pharmacist determination of interchangeability to FDA determination of interchangeability | Alabama, Alaska, California, Connecticut, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Washington |

Abbreviation: FDA, US Food and Drug Administration.

Maine, Oklahoma, and Washington, DC are not represented in the table as they had not enacted interchangeable biologic substitution carve outs as of September 1, 2019.

Discussion

Our findings highlight considerable room for optimizing state drug product selection laws to promote generic and interchangeable biologic substitution. Nearly two-thirds of states did not require pharmacists to perform substitution with an FDA-approved generic when physicians prescribe a brand-name small-molecule drug. In addition, 15% of states required patient consent. When interchangeable biosimilar drugs reach the US market, possibly as soon as late 2020, they will encounter important limits on substitution.

Prior analyses suggest that these state policy choices are important. In a national survey conducted to understand beliefs and practices related to narrow therapeutic index drug substitution, the odds of pharmacists in mandatory substitution states with a patient consent requirement not substituting initial prescriptions were nearly twice (odds ratio, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.1-3.3) those of pharmacists in mandatory substitution states without a patient consent requirement.25 In the Medicaid study by Shrank et al10 of simvastatin, substitution rates in 2006-2007 were nearly 20% higher in states with mandatory vs permissive substitution policies. Our data show that more than one-third of states still require pharmacists to notify patients of substitutions independent of the package labeling, and almost half did not explicitly protect pharmacists from liability for substitution. Research is needed to quantify the effects of these variables on pharmacists’ current practices and patient outcomes.

Overall, the variation we observed highlights an opportunity not only to reduce health system spending, but also to improve population health. Generic drugs are clinically equivalent to their brand-name counterparts and have been associated with improved medication adherence and health outcomes. For example, a study of 6 classes of medications prescribed for long-term use between 2001 and 2003 reported 13% greater adherence among patients who initiated treatment with a generic rather than a brand-name drug.5 More recently, researchers found a 6% absolute increase in the proportion of days covered (a measure of adherence) and an 8% relative reduction in all-cause mortality and hospitalization for acute coronary syndrome or stroke among initiators of generic instead of brand-name statins.6 Over time, as payers have shifted more drugs onto coinsurance tiering and more costs onto patients through higher deductible plans, the individual burden of higher drug prices has only increased.26,27,28

Optimizing state laws to facilitate generic drug substitution as the default option is an important lever to increase medication adherence and reduce excess drug spending. For the rare patients who require a brand-name drug when an interchangeable generic is available, all states allow prescribers to indicate dispense as written on prescriptions, ensuring that a brand-name drug is dispensed.29 In addition, some states have created special substitution rules for some drug classes, such as immunomodulators used in patients who have undergone transplantation or are receiving antiepileptic drugs, based on concerns that some clinicians and patients have about generic interchangeability.24 In the case of antiepileptics, well-controlled observational studies have not shown increased risk of adverse patient outcomes from generic substitution.30,31

Of special concern are the heightened requirements most states have imposed on interchangeable biosimilar substitution, in particular, the permissive substitution standard. The adoption of these laws reflects in part well-documented efforts of originator biologic manufacturers with state legislators,32 which generally have looser lobbying and transparency standards than the federal government.33 When interchangeable biosimilar agents enter the market, it will be important to assess the extent to which heightened substitution requirements suppress their uptake.

The requirement for physician authorization for substitution of refills may also have important ramifications. Because most biologics are intended for long-term use, many patients with the indicated condition will be receiving the original biologic when an interchangeable biosimilar reaches the market. Drug therapy in these patients will need to be switched—or at least be capable of being switched—to achieve the full cost-savings potential of interchangeable biosimilar agents.34

In addition, the requirement in nearly all states that pharmacists notify physicians about interchangeable biologic substitution may pose administrative challenges. For example, the logistics required to implement such a notification and acknowledgment process may vary for different electronic medical record systems and may introduce workflow challenges that pose an additional barrier to widespread use. At a minimum, states may need to be flexible about the mode and timing of this communication.

The increased complexity of biologic drugs, such as monoclonal antibodies, clotting factors, and hormones, is often presented as the justification for these heightened requirements. However, the experience of other nations that found higher biosimilar uptake compared with the US offers substantial evidence of the safety of biosimilars35 and their ability to yield cost savings.36

To best facilitate generic and interchangeable biologic use, optimization of state drug product selection laws should be coupled with educational outreach to prescribers and patients. The US Department of Health and Human Services has endorsed such efforts,37 which can help improve public confidence in the safety and efficacy of generic drugs and interchangeable biologics. Academic detailing, which uses an interactive individualized approach to convey to physicians the most current, evidence-based information on optimal care decisions, is one strategy that has been shown in randomized clinical trials to improve prescribing patient outcomes and cost containment.38,39,40 Among other benefits, well-designed and deployed educational interventions may decrease the likelihood of physicians writing dispense-as-written prescriptions and increase their likelihood of using nonproprietary names in their clinical practice.

Limitations

Limitations of our investigation warrant discussion. Although the examined variables were determined after review of literature findings and laws in a subset of states, there may have been relevant points of variation that we did not identify. It is also possible that different pharmacy state boards interpret and enforce similar laws differently. In addition, insurance management tools, such as tiering and prior authorization requirements, play a role in modifying the effect of state drug product selection laws but were not assessed in this investigation.

Conclusions

State laws governing pharmacist dispensing practices represent an important policy lever to contain increasing drug costs and improve health outcomes. The substantial variation in these laws provides opportunities to further evaluate and implement policies that promote generic and interchangeable biologic substitution.

References

- 1.Papanicolas I, Woskie LR, Jha AK. Health care spending in the United States and other high-income countries. JAMA. 2018;319(10):1024-1039. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kesselheim AS, Avorn J, Sarpatwari A. The high cost of prescription drugs in the United States: origins and prospects for reform. JAMA. 2016;316(8):858-871. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Association for Accessible Medicines The case for competition: 2019. generic drug & biosimilars access & savings in the US report. Accessed June 7, 2020. https://accessiblemeds.org/sites/default/files/2019-09/AAM-2019-Generic-Biosimilars-Access-and-Savings-US-Report-WEB.pdf

- 4.Shrank WH, Hoang T, Ettner SL, et al. The implications of choice: prescribing generic or preferred pharmaceuticals improves medication adherence for chronic conditions. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(3):332-337. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.3.332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gagne JJ, Choudhry NK, Kesselheim AS, et al. Comparative effectiveness of generic and brand-name statins on patient outcomes: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(6):400-407. doi: 10.7326/M13-2942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lo-Ciganic WH, Donohue JM, Jones BL, et al. Trajectories of diabetes medication adherence and hospitalization risk: a retrospective cohort study in a large state Medicaid program. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(9):1052-1060. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3747-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khunti K, Seidu S, Kunutsor S, Davies M. Association between adherence to pharmacotherapy and outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(11):1588-1596. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greene JA. Generic: The Unbranding Of Modern Medicine. Johns Hopkins University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dave CV, Hartzema A, Kesselheim AS. Prices of generic drugs associated with numbers of manufacturers. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(26):2597-2598. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1711899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shrank WH, Choudhry NK, Agnew-Blais J, et al. State generic substitution laws can lower drug outlays under Medicaid. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(7):1383-1390. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Growdon ME, Sacks CA, Kesselheim AS, Avorn J. Potential Medicare savings from generic substitution and therapeutic interchange of ACE inhibitors and angiotensin-II-receptor blockers. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(12):1712-1714. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sacks CA, Lee CC, Kesselheim AS, Avorn J. Medicare spending on brand-name combination medications vs their generic constituents. JAMA. 2018;320(7):650-656. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.11439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chee M, Zhang JX, Ngooi S, Moriates C, Shah N, Arora VM. Generic substitution rates of oral contraceptives and associated out-of-pocket cost savings between January 2010 and December 2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(4):561-563. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.IQVIA Medicine use and spending in the US: a review of 2017 and outlook to 2022. Published April 19, 2018. Accessed June 7, 2020. https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/medicine-use-and-spending-in-the-us-review-of-2017-outlook-to-2022

- 15.Sarpatwari A, Barenie R, Curfman G, Darrow JJ, Kesselheim AS. The US biosimilar market: stunted growth and possible reforms. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019;105(1):92-100. doi: 10.1002/cpt.1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Regulation of biological products. 42 USC §262(i) (2018).

- 17.Gabay M. Biosimilar substitution laws. Hosp Pharm. 2017;52(8):544-545. doi: 10.1177/0018578717726995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.US Food and Drug Administration FDA-approved biosimilar products. Accessed June 7, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/biosimilars/biosimilar-product-information

- 19.Luo J, Kesselheim AS, Sarpatwari A. Insulin access and affordability in the USA: anticipating the first interchangeable insulin product. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(5):360-362. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30105-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.US Food and Drug Administration Considerations in demonstrating interchangeability with a reference product. Updated May 2019. Accessed June 7, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/considerations-demonstrating-interchangeability-reference-product-guidance-industry

- 21.US Food and Drug Administration Clinical immunogenicity considerations for biosimilar and interchangeable insulin products. Published November 2019. Accessed June 7, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/clinical-immunogenicity-considerations-biosimilar-and-interchangeable-insulin-products

- 22.Reuters T. WestLaw Edge legal database. Accessed June 7, 2020. https://legal.thomsonreuters.com/en/products/westlaw

- 23.Connecticut General Statutes. Substitution of generic drugs and biological products. Definitions. Interchangeable biological products. Prescribing practitioners. Pharmacy signs. Dispensing. Records. Regulations. § 20-619(h).

- 24.Cal. Com. Code § 4073.5(b).

- 25.Sarpatwari A, Lee MP, Gagne JJ, et al. Generic versions of narrow therapeutic index drugs: a national survey of pharmacists’ substitution beliefs and practices. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;103(6):1093-1099. doi: 10.1002/cpt.884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.González López-Valcárcel B, Librero J, García-Sempere A, et al. Effect of cost sharing on adherence to evidence-based medications in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Heart. 2017;103(14):1082-1088. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-310610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heidari P, Cross W, Crawford K. Do out-of-pocket costs affect medication adherence in adults with rheumatoid arthritis? a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018;48(1):12-21. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karter AJ, Parker MM, Solomon MD, et al. Effect of out-of-pocket cost on medication initiation, adherence, and persistence among patients with type 2 diabetes: the Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). Health Serv Res. 2018;53(2):1227-1247. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shrank WH, Liberman JN, Fischer MA, et al. The consequences of requesting “dispense as written.” Am J Med. 2011;124(4):309-317. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gagne JJ, Avorn J, Shrank WH, Schneeweiss S. Refilling and switching of antiepileptic drugs and seizure-related events. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;88(3):347-353. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kesselheim AS, Bykov K, Gagne JJ, Wang SV, Choudhry NK. Switching generic antiepileptic drug manufacturer not linked to seizures: a case-crossover study. Neurology. 2016;87(17):1796-1801. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sarpatwari A, Avorn J, Kesselheim AS. Progress and hurdles for follow-on biologics. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(25):2380-2382. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1504672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whyte LE, Wieder B Amid federal gridlock, lobbying rises in the states. The Center for Public Integrity. Updated May 18, 2016. Accessed June 7, 2020. https://publicintegrity.org/politics/state-politics/amid-federal-gridlock-lobbying-rises-in-the-states/

- 34.Hakim A, Ross JS. Obstacles to the adoption of biosimilars for chronic diseases. JAMA. 2017;317(21):2163-2164. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.5202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.European Medicines Agency and European Commission. Biosimilars in the EU: information guide for healthcare professionals. Updated February 10, 2019. Accessed June 7, 2020. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/leaflet/biosimilars-eu-information-guide-healthcare-professionals_en.pdf

- 36.Troein P, Netwon M, Patel J, Scott K The impact of biosimilar competition in Europe. IQVIA. Published October 2019. Accessed May 19, 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/38461/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native

- 37.US Department of Health and Human Services American patients first: the Trump Administration blueprint to lower drug prices and reduce out-of-pocket costs. Published May 2018. Accessed June 7, 2020. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/AmericanPatientsFirst.pdf

- 38.Avorn J, Soumerai SB. Improving drug-therapy decisions through educational outreach: a randomized controlled trial of academically based “detailing.” N Engl J Med. 1983;308(24):1457-1463. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198306163082406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Avorn J, Soumerai SB, Everitt DE, et al. A randomized trial of a program to reduce the use of psychoactive drugs in nursing homes. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(3):168-173. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199207163270306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD000409. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000409.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]