Abstract

This cross-sectional study uses data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System to assess trends in e-cigarette use in the United States.

e-Cigarettes are generally perceived to be less harmful than traditional cigarettes.1 A considerable public health challenge is their use among young adults who have never smoked and among vulnerable subgroups, including individuals with mental health conditions and pregnant women.2,3,4 The rapidly evolving e-cigarette market, outdated tobacco laws and regulations, and the recent outbreak of e-cigarette or vaping product use–associated lung injuries highlight the need for up-to-date data on e-cigarette use.

Methods

We analyzed 1 156 411 participants from the nationally representative Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System 2016-2018 with information on e-cigarette use, which was categorized as never, former, or current (daily/occasional) use.3,4 We defined sole e-cigarette users as those who never use combustible cigarettes but who currently use e-cigarettes. Participants self-reported demographic information, cigarette smoking status, chronic health conditions, and health-risk behaviors (other tobacco use, heavy alcohol use, marijuana use, and binge drinking, defined elsewhere4). Data were analyzed in October 2019.

Sampling weights and methodology are described elsewhere.3,4 Current e-cigarette use prevalence was analyzed by year, and absolute differences in percentage prevalence were calculated. Trends across the years were tested using logistic regression with survey year as a continuous variable. In 2018, only 33 states had e-cigarette use documented; we therefore conducted subanalysis of trends in only these states. The data used were publicly available and deidentified; thus, this study was exempt from was institutional review board review based on the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects Revised Common Rule. The statistical software used was Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp).

Results

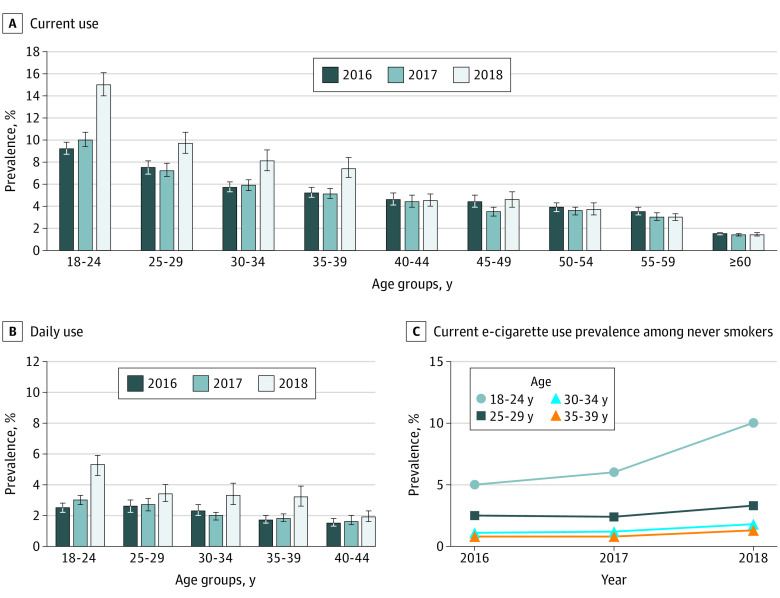

The weighted overall current e-cigarette use prevalence was 4.5% (95% CI, 4.4%-4.6%) in 2016, remained stable at 4.4% (95% CI, 4.3%-4.5%) in 2017, then increased to 5.4% (95% CI, 5.2%-5.6%) in 2018. This translates to approximately 11 200 000 adults using e-cigarettes in the US in 2016, 11 000 000 in 2017, and 13 700 000 in 2018. These trends were similar across sociodemographic subgroups (Table). The youngest age group (18-24 years) had the largest increase in prevalence, from 9.2% in 2016 to 15% in 2018, as did students, whose use increased from 6.3% in 2016 to 12% in 2018 (Figure, A). Among those who never smoked, there was a significant increase in prevalence of e-cigarette use from 1.4% in 2016 to 2.3% in 2018. Participants who participated in health-risk behaviors, including marijuana use, had higher increases in e-cigarette use prevalence compared with those who did not (Table).

Table. Characteristics and Trends of e-Cigarette Use Prevalence Among Adults in the US, 2016-2018.

| Variable | Weighted % (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2016 vs 2017 | 2017 vs 2018 | |

| Overall current e-cigarette use | 4.5 (4.4 to 4.6) | 4.4 (4.3 to 4.5) | 5.4 (5.2 to 5.6) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 5.6 (5.3 to 5.8) | 5.4 (5.2 to 5.7) | 6.9 (6.5 to 7.2) | −0.1 (−0.4 to 0.2) | 1.4 (1.0 to 1.9) |

| Female | 3.5 (3.4 to 3.7) | 3.4 (3.2 to 3.6) | 4.1 (3.9 to 4.4) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.0) |

| Age, y | |||||

| 18-24 | 9.2 (8.7 to 9.8) | 10.0 (9.4 to 10.7) | 15.0 (14.0 to 16.1) | 0.8 (−0.1 to 1.7) | 5.0 (3.8 to 6.2) |

| 25-29 | 7.5 (6.9 to 8.1) | 7.2 (6.7 to 7.9) | 9.7 (8.8 to 10.7) | −0.2 (−1.0 to 0.6) | 2.5 (1.3 to 3.6) |

| 30-34 | 5.7 (5.3 to 6.2) | 5.9 (5.4 to 6.4) | 8.1 (7.2 to 9.1) | 0.2 (−0.5 to 0.9) | 2.2 (1.1 to 3.3) |

| 35-39 | 5.2 (4.8 to 5.7) | 5.1 (4.7 to 5.6) | 7.4 (6.6 to 8.4) | −0.1 (−0.8 to 0.6) | 2.3 (1.3 to 3.4) |

| 40-44 | 4.6 (4.1 to 5.2) | 4.4 (3.9 to 5.0) | 4.5 (4.0 to 5.1) | −0.2 (−1.0 to 0.6) | 0.1 (−0.7 to 0.9) |

| 45-49 | 4.4 (3.9 to 5.0) | 3.5 (3.1 to 3.9) | 4.6 (3.9 to 5.3) | −0.9 (−1.6 to −0.3) | 1.1 (0.3 to 1.9) |

| 50-54 | 3.9 (3.5 to 4.3) | 3.6 (3.2 to 3.9) | 3.7 (3.2 to 4.3) | −0.3 (−0.9 to 0.3) | 0.1 (−0.5 to 0.8) |

| 55-59 | 3.5 (3.2 to 3.9) | 3.0 (2.7 to 3.4) | 3.0 (2.7 to 3.3) | −0.5 (−1.0 to 0.03) | −0.1 (−0.5 to 0.4) |

| ≥60 | 1.5 (1.4 to 1.6) | 1.4 (1.3 to 1.5) | 1.4 (1.3 to 1.6) | −0.1 (−0.4 to 0.3) | −0.2 (−0.7 to 0.3) |

| Race | |||||

| White | 5.1 (4.9 to 5.2) | 5.0 (4.8 to 5.2) | 5.8 (5.6 to 6.1) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.1) |

| Black or African American | 3.4 (3.1 to 3.8) | 3.2 (2.8 to 3.6) | 3.7 (3.2 to 4.2) | −0.2 (−0.8 to 0.3) | 0.5 (−0.2 to 1.1) |

| Hispanic | 2.9 (2.6 to 3.3) | 2.9 (2.6 to 3.3) | 4.9 (4.2 to 5.7) | 0.0 (−0.4 to 0.5) | 1.9 (1.1 to 2.7) |

| Other | 4.9 (4.4 to 5.5) | 4.4 (3.9 to 4.9) | 6.4 (5.7 to 7.2) | −0.5 (−1.3 to 0.3) | 1.9 (1.0 to 2.8) |

| Sexual orientation | |||||

| Heterosexual | 4.2 (4.0 to 4.4) | 4.0 (3.8 to 4.2) | 5.1 (4.9 to 5.4) | −0.2 (−0.4 to 0.1) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.4) |

| Lesbian/gay | 7.2 (5.7 to 9.1) | 6.9 (5.4 to 8.6) | 10.7 (8.2 to 13.9) | −0.3 (−2.7 to 2.0) | 3.8 (0.6 to 7.1) |

| Bisexual | 11.0 (9.3 to 13.0) | 9.5 (7.9 to 11.4) | 12.5 (10.7 to 14.6) | −1.6 (−4.1 to 1.0) | 3.0 (0.4 to 5.6) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 2.9 (2.7 to 3.0) | 2.8 (2.6 to 2.9) | 3.1 (2.9 to 3.3) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) | 0.3 (0.04 to 0.6) |

| Divorced | 5.8 (5.4 to 6.2) | 5.0 (4.6 to 5.4) | 6.3 (5.7 to 6.9) | −0.8 (−1.4 to −0.3) | 1.3 (0.6 to 2.0) |

| Widowed | 2.1 (1.9 to 2.3) | 1.9 (1.7 to 2.2) | 1.7 (1.5 to 2.1) | −0.2 (−0.5 to 0.2) | −0.1 (−0.6 to 0.3) |

| Single | 7.3 (7.0 to 7.6) | 7.5 (7.2 to 7.8) | 10.3 (9.8 to 10.8) | 0.2 (−0.3 to 0.7) | 2.8 (2.2 to 3.4) |

| Education | |||||

| <High school | 4.8 (4.4 to 5.3) | 4.6 (4.2 to 5.0) | 5.4 (4.8 to 6.1) | −0.2 (−0.8 to 0.4) | 0.8 (0.1 to 1.6) |

| High school and some college | 5.5 (5.3 to 5.7) | 5.5 (5.3 to 5.7) | 6.6 (6.3 to 6.9) | −0.03 (−0.3 to 0.3) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.5) |

| College graduate | 2.2 (2.1 to 2.3) | 2.0 (1.9 to 2.1) | 2.8 (2.6 to 3.0) | −0.2 (−0.3 to 0.0) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.1) |

| Employment status | |||||

| Employed | 4.9 (4.8 to 5.1) | 4.7 (4.6 to 4.9) | 6.1 (5.8 to 6.4) | −0.2 (−0.5 to 0.1) | 1.4 (1.0 to 1.7) |

| Unemployed | 5.6 (5.3 to 6.0) | 5.5 (5.2 to 5.9) | 5.9 (5.4 to 6.4) | −0.1(−0.5 to 0.3) | 0.4 (−0.2 to 1.0) |

| Student | 6.3 (5.6 to 7.0) | 7.2 (6.4 to 8.0) | 12.0 (10.6 to 13.6) | 0.9 (−0.2 to 1.9) | 4.8 (3.1 to 6.5) |

| Retired | 1.4 (1.3 to 1.5) | 1.3 (1.2 to 1.4) | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.7) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.0) | 0.1 (−0.1 to 0.4) |

| Income | |||||

| Below poverty line | 5.4 (5.0 to 5.8) | 5.3 (4.9 to 5.8) | 6.9 (6.3 to 7.5) | −0.1 (−0.7 to 0.5) | 1.5 (0.8 to 2.3) |

| Within 100%-200% above poverty line | 5.2 (5.0 to 5.5) | 4.6 (4.3 to 4.9) | 6.1 (5.6 to 6.6) | −0.7 (−1.1 to −0.2) | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.1) |

| >200% above poverty line | 4.0 (3.8 to 4.2) | 3.8 (3.6 to 4.0) | 5.0 (4.7 to 5.2) | −0.2 (0.4 to 0.0) | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.5) |

| Metropolitan area | |||||

| Center city | 2.8 (2.6 to 3.1) | 2.4 (2.1 to 2.7) | 2.4 (2.0 to 2.8) | −0.4 (−0.8 to −0.1) | 0.0 (−0.4 to 0.5) |

| Same county as center city | 2.7 (2.4 to 3.0) | 2.2 (1.9 to 2.6) | 3.4 (2.5 to 4.5) | −0.5 (−0.9 to 0.0) | 1.1 (0.1 to 2.2) |

| Suburban county | 3.0 (2.6 to 3.3) | 2.7 (2.3 to 3.1) | 2.9 (2.4 to 3.4) | −0.3 (−0.8 to 0.2) | 0.2(−0.4 to 0.8) |

| Outside metropolitan area | 3.5 (3.1 to 4.0) | 3.1 (2.7 to 3.5) | 2.5 (2.1 to 2.9) | −0.5 (−1.1 to 0.1) | −0.6 (−1.1 to 0.0) |

| Combustible cigarette smoking | |||||

| Never | 1.4 (1.3 to 1.5) | 1.5 (1.4 to 1.6) | 2.3 (2.1 to 2.5) | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.3) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.0) |

| Former | 5.3 (5.0 to 5.6) | 5.3 (5.0 to 5.6) | 6.9 (6.4 to 7.4) | 0.0 (−0.4 to 0.4) | 1.6 (1.0 to 2.2) |

| Current | 14.7 (14.1 to 15.2) | 13.6 (13.1 to 14.2) | 14.7 (13.9 to 15.5) | −1.0 (−1.7 to −0.2) | 1.0 (0.1 to 2.0) |

| Use of other tobacco productsa | |||||

| No | 4.3 (4.2 to 4.4) | 4.2 (4.0 to 4.3) | 5.2 (5.0 to 5.4) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.0) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) |

| Yes | 9.4 (8.5 to 10.4) | 10.1 (9.1 to 11.2) | 11.0 (9.7 to 12.4) | 0.7 (−0.7 to 2.0) | 0.9 (−0.8 to 2.6) |

| Heavy alcohol use | |||||

| No | 4.2 (4.1 to 4.3) | 4.1 (4.0 to 4.3) | 4.9 (4.7 to 5.2) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.1) |

| Yes | 8.6 (7.9 to 9.3) | 8.1 (7.4 to 8.8) | 11.5 (10.5 to 12.6) | −0.5 (−1.5 to 0.5) | 3.4 (2.1 to 4.6) |

| Marijuana use | |||||

| No | 3.9 (3.7 to 4.2) | 2.6 (2.3 to 2.8) | 3.7 (3.4 to 4.0) | −1.4 (−1.7 to −1.0) | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.6) |

| Yes | 16.2 (14.4 to 18.2) | 11.2 (9.4 to 13.3) | 21.3 (18.9 to 23.9) | −5.0 (−7.7 to −2.2) | 10.1 (6.9 to 13.2) |

| Binge drinking | |||||

| No | 3.7 (3.5 to 3.8) | 3.6 (3.5 to 3.7) | 4.2 (4.0 to 4.4) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) | 0.6 (0.3 to 0.8) |

| Yes | 8.6 (8.2 to 9.1) | 8.2 (7.8 to 8.7) | 11.8 (11.1 to 12.6) | −0.4 (−1.0 to 0.2) | 3.6 (2.8 to 4.5) |

| Cardiovascular diseaseb,c | |||||

| No | 4.7 (4.6 to 4.8) | 4.6 (4.5 to 4.8) | 6.1 (5.9 to 6.4) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.8) |

| Yes | 7.1 (6.0 to 8.3) | 7.3 (5.8 to 9.2) | 6.4 (5.2 to 7.9) | 0.3 (−1.7 to 2.3) | −0.9(−3.1 to 1.2) |

| Cancerc | |||||

| No | 4.8 (4.6 to 4.9) | 4.7 (4.5 to 4.8) | 6.1 (5.9 to 6.4) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.7) |

| Yes | 6.5 (5.6 to 7.5) | 6.6 (5.5 to 7.8) | 8.0 (6.4 to 10.0) | 0.1 (−1.4 to 1.5) | 1.5(−0.7 to 3.6) |

| Asthmac | |||||

| No | 4.5 (4.4 to 4.7) | 4.4 (4.3 to 4.6) | 5.8 (5.6 to 6.1) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.2) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.7) |

| Yes | 6.7 (6.2 to 7.2) | 6.2 (5.7 to 6.8) | 7.7 (6.9 to 8.5) | −0.5 (−1.2 to 0.3) | 1.5 (0.5 to 2.5) |

| COPDc | |||||

| No | 4.5 (4.4 to 4.7) | 4.5 (4.3 to 4.6) | 5.9 (5.7 to 6.1) | −0.05 (−0.3 to 0.2) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.7) |

| Yes | 10.2 (9.2 to 11.2) | 9.3 (8.3 to 10.4) | 11.7 (10.2 to 13.4) | −0.9 (−2.4 to 0.5) | 2.4 (0.5 to 4.3) |

| Diabetesc | |||||

| No | 4.8 (4.7 to 5.0) | 4.7 (4.5 to 4.8) | 6.2 (5.9 to 6.4) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.8) |

| Prediabetes | 5.0 (3.8 to 6.4) | 5.2 (3.5 to 7.6) | 8.4 (5.4 to 12.9) | 0.2 (−2.2 to 2.6) | 3.2 (−1.0 to 7.4) |

| Yes | 5.0 (4.4 to 5.7) | 5.8 (4.7 to 7.1) | 6.2 (4.9 to 7.7) | 0.8 (−0.6 to 2.1) | 0.4 (−1.4 to 2.2) |

| Chronic kidney diseasec | |||||

| No | 4.8 (4.6 to 4.9) | 4.7 (4.6 to 4.9) | 6.1 (5.9 to 6.4) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.8) |

| Yes | 6.5 (5.3 to 8.0) | 5.9 (4.6 to 7.5) | 7.1 (5.0 to 9.8) | −0.7 (−2.6 to 1.3) | 1.2 (−1.5 to 4.0) |

| Depressionc | |||||

| No | 3.9 (3.8 to 4.1) | 3.8 (3.7 to 4.0) | 5.2 (4.9 to 5.5) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.7) |

| Yes | 9.1 (8.7 to 9.5) | 8.5 (8.1 to 8.9) | 10.2 (9.6 to 10.8) | −0.6 (−1.2 to −0.06) | 1.7 (1.0 to 2.4) |

Abbreviation: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Defined as current use of chewing tobacco, snuff, or snus every day or some days.

Defined as history of myocardial infarction, stroke, angina, or coronary heart disease.

Age standardized estimates are shown.

Figure. e-Cigarette Use Among Adults in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2016 to 2018.

Trends in current e-cigarette use prevalence by age (A); trends in daily e-cigarette use by age (B), in which the proportion of current users (daily to current use ratio) increased from 2016 to 2018; and trends in e-cigarette prevalence by age (C), including current e-cigarette use prevalence among those who have never smoked. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Daily and occasional use prevalence increased from 2016 to 2018, with the largest change observed among 18- to 24-year-olds. The proportion of current users who used e-cigarettes daily (daily to current use ratio) also increased (Figure, B). Among those who never smoked, current e-cigarette use prevalence increased from 1.4% in 2016 to 2.3% in 2018, translating to approximately 3 500 000 adults in 2016 and 5 800 000 adults in 2018. The group of 18- to 24-year-olds had the highest prevalence of sole use each year (Figure, C). Trends in e-cigarette use in the 50 states and 3 territories included in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System were heterogenous but showed generally similar trends; trend analysis in the 33 states with complete data were consistent with the overall findings of this study.

Discussion

Findings from this nationally representative sample of US adults, including state-level analysis, show stable e-cigarette use prevalence between 2016 and 2017, followed by a marked increase from 2017 to 2018. We observed a shift toward daily use and sole e-cigarette use, and a significant increase in use among younger adults, especially students.

While our study is the largest analysis to date that assesses the trends in current e-cigarette and sole e-cigarette use in U.S. adults, it has a few limitations. All data were also self-reported, so we cannot exclude some misclassification and information bias. Additionally, social desirability and recall bias may have led to underreporting of e-cigarette use and cigarette smoking status.

Previous studies report a strong association between exposure to e-cigarette marketing and its subsequent use.5 We speculate that increased e-cigarette advertisement expenditure over the years and increased social media presence correlates with increased e-cigarette use, especially in the youngest age group. The significant increase in daily e-cigarette use suggests that more users are becoming dependent on e-cigarettes rather than merely experimenting with them. This is concerning among younger adults because early use of e-cigarettes has been associated with subsequent cigarette smoking, as well as drug and alcohol use.6 The increase in e-cigarette use among individuals exhibiting other health-risk behaviors, particularly marijuana use, is concerning especially in light of the outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injuries that has been linked to the vaping of tetrahydrocannabinoids.

References

- 1.Goniewicz ML, Lingas EO, Hajek P. Patterns of electronic cigarette use and user beliefs about their safety and benefits: an internet survey. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2013;32(2):133-140. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00512.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu B, Xu G, Rong S, et al. National estimates of e-cigarette use among pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age in the United States, 2014-2017. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(6):600-602. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Obisesan OH, Mirbolouk M, Osei AD, et al. Association between e-cigarette use and depression in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2016-2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(12):e1916800. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.16800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mirbolouk M, Charkhchi P, Kianoush S, et al. Prevalence and distribution of e-cigarette use among U.S. adults: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2016. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):429-438. doi: 10.7326/M17-3440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pierce JP, Sargent JD, Portnoy DB, et al. Association between receptivity to tobacco advertising and progression to tobacco use in youth and young adults in the PATH study. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(5):444-451. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.5756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silveira ML, Conway KP, Green VR, et al. Longitudinal associations between youth tobacco and substance use in waves 1 and 2 of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;191:25-36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.06.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]