Key Points

Question

What are the trends of utilization and spending on brand-name and generic formulations of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C)–lowering therapies among Medicare beneficiaries between 2014 and 2018?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of the Medicare Part D database, between 2014 and 2018, prescription of LDL-C–lowering therapies increased 23% while total expenditures decreased 46% among Medicare beneficiaries, largely driven by greater use of generic statin formulations. PCSK9 inhibitor use and spending increased 144% and 199%, respectively, over the study period; an additional $2.5 billion could have been saved if generic substitution occurred once available.

Meaning

Medicare expenditures on LDL-C–lowering therapy have declined despite increasing use driven by rapid and sustained uptake of generic formulations; however, further work is needed to ensure cost does not become a barrier to care.

This cross-sectional study evaluates trends in utilization and spending on brand-name and generic low-density lipoprotein cholesterol–lowering therapies and estimates potential savings if all Medicare beneficiaries were switched to available therapeutically equivalent generic formulations.

Abstract

Importance

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C)–lowering therapies are a cornerstone of prevention in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. With the introduction of generic formulations and the release of new therapies, including proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors, contemporary Medicare utilization of these therapies remains unknown.

Objective

To determine trends in utilization and spending on brand-name and generic LDL-C–lowering therapies and to estimate potential savings if all Medicare beneficiaries were switched to available therapeutically equivalent generic formulations.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study analyzed prescription drug utilization and cost trend data from the Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Event data set from 2014 to 2018 for LDL-C–lowering therapies. A total of 11 LDL-C–lowering drugs with 25 formulations, including 16 brand-name and 9 generic formulations, were included. Data were collected and analyzed from October 2019 to June 2020.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Number of Medicare Part D beneficiaries, annual spending, and spending per beneficiary for all formulations.

Results

The total number of Medicare Part D beneficiaries ranged from 37 720 840 in 2014 to 44 249 461 in 2018. The number of Medicare beneficiaries taking LDL-C–lowering therapies increased by 23% (from 20.5 million in 2014 to 25.2 million in 2018), while the associated Medicare expenditure decreased by 46% (from $6.3 billion in 2014 to $3.3 billion in 2018). Lower expenditure was driven by greater uptake of generic statin and ezetimibe and a concurrent rapid decline in the use of their brand-name formulations. Medicare spent $9.6 billion on brand-name statins and ezetimibe and could have saved $2.1 billion and $0.4 billion, respectively, if brand-name formulations were switched to equivalent generic versions when available. The number of beneficiaries using PCSK9 inhibitors since their introduction in 2015 has been modest, although use has increased by 144% (from 25 569 in 2016 to 62 476 in 2018) and total spending has increased by 199% (from $164 million in 2016 to $491 million in 2018).

Conclusions and Relevance

Between 2014 and 2018, LDL-C–lowering therapies were used by 4.8 million more Medicare beneficiaries annually, with an associated $3.0 billion decline in Medicare spending. This cost reduction was driven by the rapid transition from brand-name formulations to lower-cost generic formulations of statins and ezetimibe. Use of PCSK9 inhibitions, although low, increased over time and could have broad implications on future Medicare spending.

Introduction

The landscape of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C)–lowering therapies has evolved over the last few years with the introduction of new generic drugs (rosuvastatin, ezetimibe, fluvastatin extended-release) and brand-name drugs (evolocumab, alirocumab). However, the contemporary patterns of utilization and spending on LDL-C–lowering therapies are unknown. This represents an important knowledge gap, as prescription drug costs contribute significantly to the increasing health system expenditure as well as to the growing burden of out-of-pocket spending among patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).1,2 Accordingly, we evaluated the trends in utilization and spending on different LDL-C–lowering therapies (statin and nonstatin) among Medicare Part D beneficiaries.

Methods

We analyzed the publicly available Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Event data set from January 2014 to December 2018,3 which contains outpatient medication expenditures for all Medicare Part D beneficiaries for approximately 70% of the Medicare population (eMethods 1 in the Supplement). This data set contains 3474 formulations and reports the drug-specific total annual spending by Medicare. We extracted number of beneficiaries, annual spending, and spending per beneficiary for all formulations (generic, brand-name, and combination drugs) of statins, ezetimibe, and the proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors alirocumab and evolocumab. We identified annual Medicare Part D utilization (overall and per 10 000 beneficiary rate) and spending trends of LDL-C–lowering therapies. If an identical generic formulation was available for a given year, we estimated the possible savings with the following formula: (per-beneficiary brand-name spending − per-beneficiary generic spending) × beneficiaries taking brand-name formulation. Annual spending and savings were adjusted for inflation and reported in 2018 US dollars. Postrebate spending was estimated using the 2014 cardiovascular brand-name rebate rate of 26.3% (eMethods 2 in the Supplement).4 The yearly aggregate total cost share for statins incurred by beneficiaries (with and without low-income subsidies) was obtained from the publicly available Medicare Part D Prescriber National Summary Report5 files for 2013 to 2017 (eMethods 3 in the Supplement). The study used publicly available data and was considered exempt from institutional review board review and approval. All analyses were performed in Microsoft Excel version 16.0 (Microsoft) and GraphPad Prism version 7.0 (GraphPad Software).

Results

The total number of Medicare Part D beneficiaries ranged from 37 720 840 in 2014 to 44 249 461 in 2018. This analysis included 11 drugs with 25 formulations, including 16 brand-name formulations and 9 generic formulations (Table). Between 2014 to 2018, the total number of Medicare Part D enrollees increased by 17% (from 37.7 million in 2014 to 44.2 million in 2018). Total prescriptions for LDL-C–lowering therapies increased by 23% (from 20.5 million in 2014 to 25.2 million in 2018), which corresponded to a 5.2% increase in the prescription rate per 10 000 Medicare beneficiaries (from 5391 per 10 000 beneficiaries in 2014 to 5671 per 10 000 beneficiaries in 2018). The total Medicare expenditure on LDL-C–lowering therapies declined by 46% (from $6.3 billion in 2014 to $3.3 billion in 2018).

Table. Utilization of Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol–Lowering Therapies and Associated Cost Among Medicare Part D Beneficiaries From 2014 to 2018.

| Drug name | Brand-name or generic formulation | Years analyzed | Beneficiaries, No. in thousands | Total spending, $ in millionsa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First full year of availability | 2018 | Average annual change, % | First full year of availability | 2018 | Average annual change, % | |||

| Statin therapies | ||||||||

| Lipitor (atorvastatin) | Brand-name | 2014-2018 | 39.3 | 24.0 | −10 | 54.2 | 75.8 | 11 |

| Atorvastatin calcium | Generic | 2014-2018 | 6741.2 | 11 863.3 | 15 | 828.1 | 881.1 | 2 |

| Lescol XL (fluvastatin ER) | Brand-name | 2014-2018 | 10.7 | 0.8 | −45 | 19.2 | 2.1 | −40 |

| Fluvastatin ER | Generic | 2016-2018 | 5.2 | 4.6 | −6 | 7.2 | 6.2 | −7 |

| Fluvastatin sodium | Generic | 2014-2018 | 10.2 | 8.1 | −6 | 9.0 | 6.7 | −7 |

| Altoprev (lovastatin) | Brand-name | 2014-2018 | 1.1 | 0.4 | −20 | NAb | 2.2 | NA |

| Lovastatin | Generic | 2014-2018 | 1226.8 | 1016.7 | −5 | 93.2 | 54.1 | −12 |

| Pravachol (pravastatin) | Brand-name | 2014-2018 | 2.0 | 1.3 | −11 | 2.4 | 1.6 | −9 |

| Pravastatin sodium | Generic | 2014-2018 | 3031.2 | 2920.4 | −1 | 499.6 | 307.7 | −11 |

| Crestor (rosuvastatin) | Brand-name | 2014-2018 | 1752.7 | 56.1 | −43 | 2832.6 | 77.3 | −44 |

| Rosuvastatin calciumc | Generic | 2016-2018 | 1224.0 | 2705.7 | 50 | 382.8 | 527.3 | 22 |

| Zocor/FloLipid (simvastatin) | Brand-name | 2014-2018 | 6.1 | 1.8 | −25 | 8.3 | 3.3 | −19 |

| Simvastatin | Generic | 2014-2018 | 6769.3 | 5531.7 | −5 | 377.4 | 208.3 | −13 |

| Livalo/Zypitamag (pitavastatin) | Brand-name | 2014-2018 | 57.4 | 71.3 | 6 | 58.5 | 135.1 | 23 |

| All brand-name statins (aggregate) | Brand-name | 2014-2018 | 1869.3 | 155.7 | −36 | 2975.2 | 297.5 | −33 |

| All generic statins (aggregate) | Generic | 2014-2018 | 17 778.6 | 24 050.4 | 8 | 1807.3 | 1991.3 | 3 |

| Cholesterol absorption inhibitors | ||||||||

| Zetia (ezetimibe) | Brand-name | 2014-2018 | 687.4 | 28.8 | −34 | 1152.6 | 36.5 | −30 |

| Ezetimibe | Generic | 2017-2018 | 586.1 | 798.7 | 36 | 461.9 | 392.7 | −15 |

| Combinations | ||||||||

| Vytorin (ezetimibe/simvastatin) | Brand-name | 2014-2018 | 199.1 | 8.6 | −41 | 329.3 | 17.8 | −39 |

| Ezetimibe/simvastatin | Generic | 2018 | NAb | 70.5 | NA | NAb | 71.8 | NA |

| PCSK9 inhibitors | ||||||||

| Praluent (alirocumab) | Brand-name | 2016-2018 | 15.9 | 24.1 | 23 | 102.1 | 211.9 | 46 |

| Repatha (evolocumab) | Brand-name | 2016-2018 | 9.7 | 38.4 | 101 | 61.5 | 278.8 | 115 |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9.

Annual spending and savings were adjusted for inflation and reported in 2018 US dollars.

Data not reported in Medicare data set.

Rosuvastatin calcium was available starting in the second quarter of 2016.

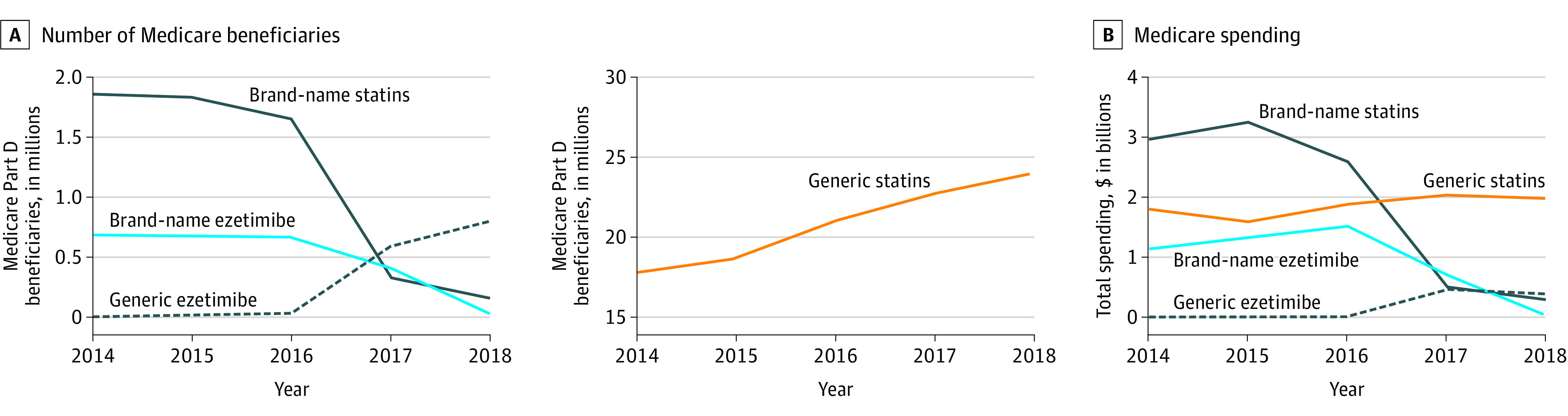

Statins

Between 2014 and 2018, statin use increased by 23% (from 19.6 million beneficiaries in 2014 to 24.2 million beneficiaries in 2018), with a 35% increase in use of generic formulations (from 17.8 million in 2014 to 24 million in 2018) and a 92% decline in use of brand-name formulations (from 1.9 million in 2014 to 155 711 in 2018) (Figure 1A). Similar trends were noted in prescription rates (per 10 000 Medicare beneficiaries) of generic and brand-name formulations (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Overall spending on statins declined by 52% (from $4.8 billion in 2014 to $2.3 billion in 2018), and per-beneficiary spending decreased by 61% (from $243 in 2014 to $95 in 2018) (Figure 1B). Despite these declines, Medicare spent $9.6 billion on brand-name statins during the study period and could have saved an additional $2.1 billion ($1.4 billion with rebates) by switching to equivalent generic options when available.

Figure 1. Temporal Trends in Statin and Ezetimibe Use and Spending From 2014 to 2018 Among Medicare Beneficiaries.

A, Number of Medicare Part D beneficiaries receiving a statin or ezetimibe prescription from January 2014 to December 2018. B, Total Medicare spending on statins and ezetimibe from January 2014 to December 2018. Annual spending and savings were adjusted for inflation and reported in 2018 US dollars.

For statins with available generic formulations before 2014 (lovastatin, pravastatin, simvastatin, and atorvastatin), the proportional use of brand-name formulations in 2014 was low (0.5% or less) and amounted to less than 10% of each drug’s total expenditures. Following release of generic rosuvastatin in 2016, the total spending and number of beneficiaries prescribed brand-name rosuvastatin decreased by 97% (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). Furthermore, the annual aggregate total cost paid by beneficiaries with and without the low-income subsidy for statins decreased by 14% and 24%, respectively, between 2013 and 2017 (eFigure 3 in the Supplement). As of 2018, brand-name statins represented 0.6% of all statin prescriptions and 13% of statin expenditures.

Nonstatins

Between 2014 and 2018, the number of beneficiaries prescribed ezetimibe increased by 20% (from 687 000 in 2014 to 827 000 in 2018). Following the release of generic ezetimibe in 2016, prescriptions for brand-name ezetimibe declined by 96% (Figure 1A). Similar trends were noted in prescription rates for brand-name ezetimibe (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Total spending on ezetimibe decreased by 62% (from $1.2 billion in 2014 to $429 million in 2018), with a corresponding 69% decrease in per-beneficiary spending (from $1677 in 2014 to $519 in 2018). Medicare spent $5.6 billion on brand-name ezetimibe over the study period, and switching to generic ezetimibe when available (starting in 2017) could have saved $0.4 billion ($0.2 billion with rebates).

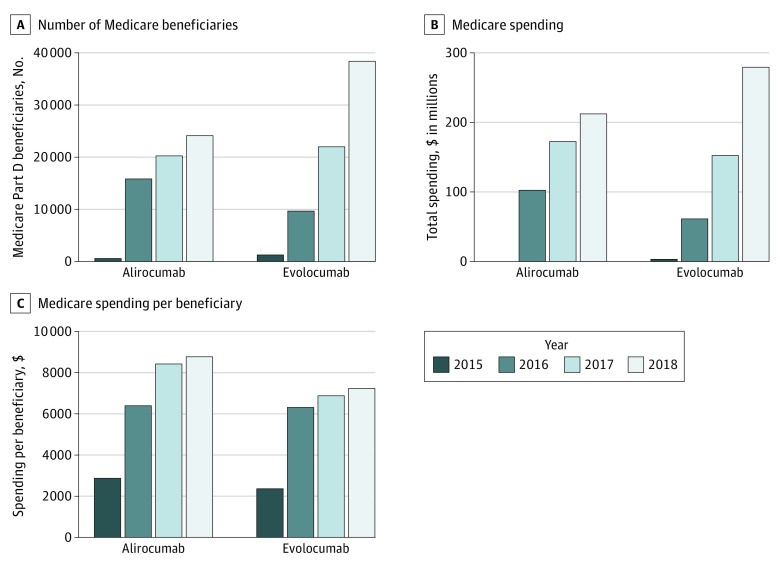

The number of beneficiaries using PCSK9 inhibitors was low and increased by 144% between 2016 and 2018 (from 25 569 in 2016 to 62 476 in 2018) (Figure 2A), which corresponded to a 2-fold increase in the prescription rate per 10 000 beneficiaries (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). The total spending on PCSK9 inhibitors increased by 199% (from $164 million in 2016 to $491 million in 2018), translating to a 23% increase in average per-beneficiary spending (from $6399 in 2014 to $7853 in 2018) (Figure 2B and C). In 2018, the average spending per Medicare beneficiary was $8746 for alirocumab and $7267 for evolocumab (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Temporal Trends in PCSK9 Inhibitor Use and Spending From 2015 to 2018 Among Medicare Beneficiaries.

A, Number of Medicare Part D beneficiaries receiving a PCSK9 inhibitor prescription from January 2015 to December 2018. B, Total Medicare spending on PCSK9 inhibitors from January 2015 to December 2018. C, Medicare spending per beneficiary for those receiving a PCSK9 inhibitor prescription from January 2015 to December 2018. Annual spending and savings were adjusted for inflation and reported in 2018 US dollars.

Discussion

We observed that the Medicare expenditures on LDL-C–lowering therapies have declined despite a substantial increase in their use driven by rapid uptake of generic formulations of statins and ezetimibe. These findings are particularly relevant as prescription drug costs contribute to the high health care expenditure burden and associated medication nonadherence among patients with ASCVD.2,6 Substitution of costly brand-name drugs with therapeutically comparable generic formulations has been proposed as an effective strategy to lower medication cost and improve adherence.7,8 Our study provides evidence in support of this notion by demonstrating substantial uptake of generic formulations over therapeutically equivalent brand-name counterparts and a concurrent reduction in the associated Medicare and beneficiary expenditure.

The increasing uptake of statins has important public health implications in reducing the burden of ASCVD. The rates of ASCVD events have declined over the past 2 decades, with some plateauing noted over the past few years.9,10 While a causal association between rates of statin and ASCVD events may not be established based on these observations,11 future studies linking Medicare Part D data with patient-level data may provide more insights.

There does appear to be a lag in the time needed for full transition from brand-name to generic formulations. However, within 2 years of the release of generic rosuvastatin, more than 99% of Medicare beneficiaries prescribed a statin were taking a generic formulation. Reasons for the small fraction of ongoing brand-name use are not well established and may be due to patient preference, clinician inertia, or other plan-specific factors.12 As this small fraction represents a disproportionate amount of total spending on statins (13%), efforts should be made to further decrease brand-name statin use.

Among newer therapies, the overall use of PCSK9 inhibitors was low immediately after approval but increased over time. The pattern of uptake of PCSK9 inhibitors among Medicare beneficiaries is similar to that observed for other novel cardiovascular therapies.13 The increasing use may be related to greater coverage of PCSK9 inhibitors by Medicare plans and improved ease of prescribing.14 However, the price of PCSK9 inhibitors remains high, and future studies are needed to determine if the recent manufacturer-proposed price reductions may accelerate its uptake.15

Limitations

The major limitations of our study include the lack of patient-level data on indications for LDL-C–lowering therapies, incidence of ASCVD events, and associated out-of-pocket expenditure. Furthermore, Medicare individual drug rebates are unavailable; thus, we used aggregate rebate amounts for adjusting the drug costs.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this cross-sectional study found that overall spending on LDL-C–lowering therapies is decreasing despite increasing use due to the rapid uptake of generic formulations of statins and ezetimibe. In contrast, Medicare spending on PCSK9 inhibitors is increasing, and the future implications of these and other novel, expensive LDL-C–lowering therapies on the care practices in our health system remains to be determined.

eMethods 1. Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Event Dataset.

eMethods 2. Medicare Part D and manufacturer drug rebates.

eMethods 3. Medicare Part D Prescriber National Summary report.

eFigure 1. Temporal trends in prescription rates (per 10 000 Medicare beneficiaries) for LDL-lowering therapies between 2014 and 2018.

eFigure 2. Proportion of beneficiaries or spending on brand-name formulations relative to combined brand-name and generic formulations.

eFigure 3. Trends in annual aggregate cost sharing of Medicare Part D beneficiaries for statin prescriptions with and without the low-income subsidy.

References

- 1.Shaw LJ, Goyal A, Mehta C, et al. 10-Year resource utilization and costs for cardiovascular care. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(10):1078-1089. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.12.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khera R, Valero-Elizondo J, Okunrintemi V, et al. Association of out-of-pocket annual health expenditures with financial hardship in low-income adults with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the United States. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(8):729-738. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.1813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Medicare Part D Drug Spending Dashboard & data. Accessed May 16, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Information-on-Prescription-Drugs/MedicarePartD

- 4.Turnbull FM, Abraira C, Anderson RJ, et al. ; Control Group . Intensive glucose control and macrovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2009;52(11):2288-2298. Published correction appears in Diabetologia. 2009;52(1):2470. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1470-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Part D prescriber data CY 2017. Accessed May 1, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Provider-Charge-Data/PartD2017

- 6.Khera R, Valero-Elizondo J, Das SR, et al. Cost-related medication nonadherence in adults with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the United States, 2013 to 2017. Circulation. 2019;140(25):2067-2075. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.041974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warraich HJ, Salami JA, Khera R, Valero-Elizondo J, Okunrintemi V, Nasir K. Trends in use and expenditures of brand-name atorvastatin after introduction of generic atorvastatin. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(5):719-721. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gagne JJ, Choudhry NK, Kesselheim AS, et al. Comparative effectiveness of generic and brand-name statins on patient outcomes: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(6):400-407. doi: 10.7326/M13-2942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, et al. ; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics—2020 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141(9):e139-e596. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chi GC, Kanter MH, Li BH, et al. Trends in acute myocardial infarction by race and ethnicity. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(5):e013542. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Heart Association; American Stroke Association . Cardiovascular disease: a costly burden for America: projections through 2035. Accessed October 4, 2018. https://healthmetrics.heart.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Cardiovascular-Disease-A-Costly-Burden.pdf

- 12.Luo J, Kesselheim AS. Delayed generic market saturation after patent expiration—a billion-dollar problem. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(5):721-722. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sumarsono A, Vaduganathan M, Ajufo E, et al. Contemporary patterns of Medicare and Medicaid utilization and associated spending on sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine in heart failure. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;5(3):336-339. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.4982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kazi DS, Lu CY, Lin GA, et al. Nationwide coverage and cost-sharing for PCSK9 inhibitors among Medicare Part D plans. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(10):1164-1166. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.3051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dangi-Garimella S. Amgen announces 60% reduction in list price of PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab. Accessed March 3, 2020. https://www.ajmc.com/view/amgen-announces-60-reduction-in-list-price-of-pcsk9-inhibitor-evolocumab

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods 1. Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Event Dataset.

eMethods 2. Medicare Part D and manufacturer drug rebates.

eMethods 3. Medicare Part D Prescriber National Summary report.

eFigure 1. Temporal trends in prescription rates (per 10 000 Medicare beneficiaries) for LDL-lowering therapies between 2014 and 2018.

eFigure 2. Proportion of beneficiaries or spending on brand-name formulations relative to combined brand-name and generic formulations.

eFigure 3. Trends in annual aggregate cost sharing of Medicare Part D beneficiaries for statin prescriptions with and without the low-income subsidy.