Abstract

This quality improvement study describes representation of women within leadership committees of clinical trials and in lead authorship positions of ensuing cardiovascular trial publications.

It is well documented that women are underrepresented in leadership within academic medicine. In biomedical sciences, they account for almost half of postdoctoral fellows but only 19% of tenured senior investigators.1 Cardiology lags behind other internal medicine specialties with regard to women entering the field and achieving leadership positions.2 However, little is known about women in cardiovascular clinical trial leadership. In this study, we describe their representation within leadership committees of clinical trials, as well as in lead authorship positions of ensuing trial publications.

Methods

Because this quality improvement study did not involve patients, it was not subject to approval per the institutional review board specifications at the Cleveland Clinic. For this study, we included cardiovascular medicine publications presenting clinical trial results published in JAMA, The Lancet, and New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2018. Leadership committees were identified from the publication or trial web page. Steering committees were obtained preferentially and included executive committees when listed separately. Executive committees were used if no steering committee was present. If neither were available, investigators listed under “primary contributors” or “study oversight” were used. These individuals are collectively referred to as leadership committees.

Data were analyzed from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2018. We used Google searches to divide authors and leadership committee members by gender, as identified by photographs, gender pronouns, and presentation of self on institutional websites and social media. Gender grouping was confirmed by 2 reviewers (K.J.D. and N.S.).

Results

We identified 200 cardiovascular medicine trial publications during the study period, including 89 in NEJM, 41 in JAMA, and 70 in The Lancet. Steering and/or executive committees were used in 152 of 200 publications (76.0%). Primary contributors or study oversight committees were used in 48 of 200 studies (24.0%).

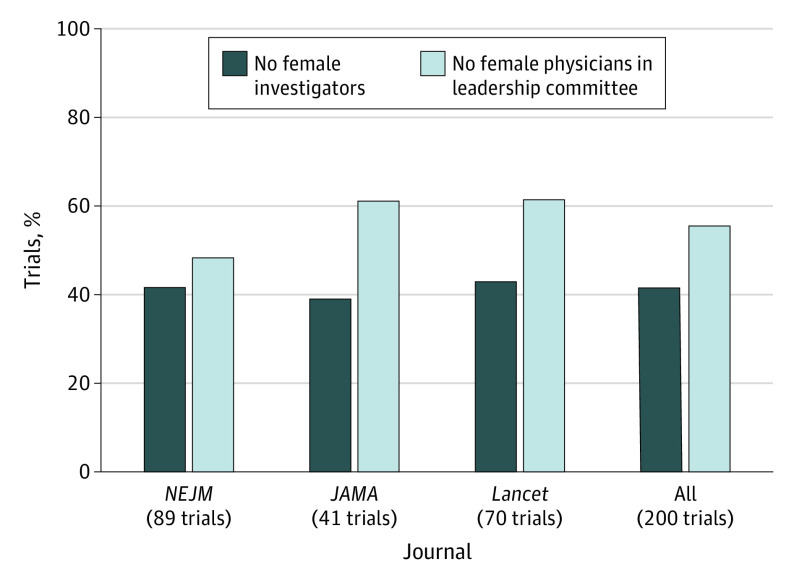

Of 2433 leadership committee members, 270 (11.1%) were women, with women representing a median of 10.1% (range, 0%-57.1%) of committees, including 9.4% for NEJM, 8.9% for The Lancet, and 13.9% for JAMA. Female physicians represented a mean of 5.4% to 6.3% of leadership committees. Among these 200 trials, 83 (41.5%) had no female investigators and 111 (55.5%) had no female physicians on their leadership committees (Figure). Only 19 of 200 trials (9.5%) included greater than 25% women in their leadership committees.

Figure. Proportion of Women as Cardiovascular Clinical Trial Investigators and in Leadership Committees.

NEJM indicates New England Journal of Medicine.

Women accounted for 18.5 of 200 first authors (9.3%) and 20 last authors (10.0%), ranging from 5 of 70 (7.1%) for The Lancet to 5 of 41 (12.2%) for JAMA for first authors and from 6 of 70 (8.6%) for The Lancet to 7 of 41 (17.1%) for JAMA for last authors. In large and procedurally oriented trials, even fewer women were represented in first and last author positions, with 2 (6.7%) JAMA to 4 (8.9%) NEJM first authors and 2 (4.3%) NEJM to 4 (13.3%) JAMA last authors (Table).

Table. Comparison of First and Last Authors by Journal.

| Journal | No. of trials | No. (%) of trials with female authors | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First author | Last author | ||

| Total trials | |||

| JAMA | 41 | 5 (12.2) | 7 (17.1) |

| The Lancet | 70 | 5 (7.1) | 6 (8.6) |

| NEJM | 89 | 8.5 (9.6) | 7 (7.9) |

| Total | 200 | 18.5 (9.3) | 20 (10.0) |

| Large trialsa | |||

| JAMA | 25 | 4 (16.0) | 2 (8.0) |

| The Lancet | 46 | 2 (4.3) | 3 (6.5) |

| NEJM | 77 | 7.5 (9.7) | 6 (7.8) |

| Total | 148 | 13.5 (9.1) | 11 (7.4) |

| Procedural trialsb | |||

| JAMA | 30 | 2 (6.7) | 4 (13.3) |

| The Lancet | 45 | 4 (8.9) | 3 (6.7) |

| NEJM | 47 | 2.5 (5.3) | 2 (4.3) |

| Total | 122 | 8.5 (7.0) | 9 (7.4) |

Abbreviation: NEJM, New England Journal of Medicine.

Indicates more than 500 participants.

Includes those in the fields of interventional cardiology and electrophysiology.

Discussion

Analysis of the representation of women leaders in cardiovascular clinical trials revealed the following. First, women constituted only 10.1% of clinical trial leadership committees; this is substantially lower than the already low proportion of women physicians or investigators in the cardiovascular therapeutic area. Second, 55.5% of leadership committees had no female representation. Third, cardiovascular clinical trial publications had women in only 9.3% of the first or 10.0% of the last author position.

Our findings provide additional evidence of gender disparities in scientific leadership. Prior research suggests that research teams with gender heterogeneity may produce higher quality research.3 Greater visibility of women in clinical trial leadership positions can enhance recruitment of female trial participants and attract more female investigators to cardiovascular clinical research. Although we did not study causality, unconscious biases may lead to discrimination in clinical trial leader selection on the basis of gender.4 A vicious cycle has been observed for women in academic medicine, with the exclusion of women leading to further exclusion, lack of recognition, and slow rates of promotion.5 Many of these factors are likely contributory; this disparity and lack of inclusion is a multifactorial problem that warrants further research.

This study has limitations, including human error in gender determination and a binary gender system. Authorship and trial committees are components of leadership and may overestimate or underestimate the true presence of women in clinical trial leadership roles.

References

- 1.Martinez ED, Botos J, Dohoney KM, et al. Falling off the academic bandwagon. Women are more likely to quit at the postdoc to principal investigator transition. EMBO Rep. 2007;8(11):977-981. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lau ES, Wood MJ. How do we attract and retain women in cardiology? Clin Cardiol. 2018;41(2):264-268. doi: 10.1002/clc.22921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell LG, Mehtani S, Dozier ME, Rinehart J. Gender-heterogeneous working groups produce higher quality science. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e79147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duch J, Zeng XH, Sales-Pardo M, et al. The possible role of resource requirements and academic career-choice risk on gender differences in publication rate and impact. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e51332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hasebrook J. Medicine goes female: threat or chance for hospitals—an international perspective In: Hahnenkamp K, Hasebrook J, eds. Rund auf eckig: Die Junge Ärztegeneration im Krankenhaus. Medhochzwei; 2015:109-127. [Google Scholar]