This difference-in-differences cohort study evaluates whether state laws that raised the minimum age to purchase and/or possess a handgun to 21 years were associated with lower rates of firearm homicide perpetrated by young adults aged 18 to 20 years.

Key Points

Question

Are state laws that raise the minimum age to purchase and/or possess a handgun associated with lower rates of firearm homicide perpetrated by young adults?

Findings

In this difference-in-differences analysis of a national cohort, there was no statistically significant change in the rates of homicide perpetrated by young adults aged 18 to 20 in states that implemented stricter minimum age laws compared with those that did not.

Meaning

Implementation of stricter minimum age laws for firearm purchase or possession was not associated with lower rates of firearm homicides perpetrated by young adults; policies limiting access through informal channels may have greater effect.

Abstract

Importance

Laws mandating a minimum age to purchase or possess firearms are viewed as a potentially effective policy tool to reduce homicide by decreasing young adults’ access to firearms.

Objective

To evaluate whether state laws that raised the minimum age to purchase and/or possess a handgun to 21 years were associated with lower rates of firearm homicide perpetrated by young adults aged 18 to 20 years.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this difference-in-differences analysis of a national cohort, young adult–perpetrated homicide rates were compared between states that did and did not implement stricter minimum age laws than the 1994 federal statute, adjusting for state-level factors. Under 1994 US federal law, the minimum age to purchase a handgun from a licensed dealer is 21 years; to purchase a handgun from an unlicensed dealer, 18 years; and to possess a handgun, 18 years. The 12 states that raised the minimum ages to purchase and/or possess a handgun beyond those set by federal law before 1994 were excluded from the stricter implementation group. Data were collected from January 1, 1995, to December 31, 2017, and analyzed from November 7, 2019, to June 23, 2020.

Exposures

Implementation of state law to raise the minimum age to purchase and/or possess a handgun beyond federal minimum age laws. During the study period, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, and Wyoming raised the minimum age from 18 to 21 years to purchase a handgun from all dealers. With the exception of Wyoming, these states also increased the minimum age from 18 to 21 years to possess a handgun.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Firearm homicides perpetrated by young adults aged 18 to 20 years. Homicide data were obtained from the Supplementary Homicide Reports.

Results

During the study period, 35 960 firearm homicides were perpetrated by young adults aged 18 to 20 years. There was no statistically significant change in the rates of homicide perpetrated by this age group in the 5 states that imposed stricter age limits compared with the 32 that did not (crude incidence rate ratio, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.86-1.40). The adjusted incidence rate ratio was 1.14 (95% CI, 0.89-1.45) in states that implemented stricter minimum age laws compared with those that did not.

Conclusions and Relevance

This study found that stricter state minimum age laws were not associated with significantly lower rates of young adult–perpetrated homicide in states that adopted them compared with states that did not, and policy makers should reassess their use.

Introduction

Firearm violence disproportionately involves young adults, both as victims and as perpetrators. In 2017, 11% of those who died due to firearm homicide and 10% of known perpetrators were aged 18 to 20 years, although this age group made up only 4% of the US population.1,2,3 Youth and young adults are at higher risk of violent behavior toward themselves and others, owing in part to biological processes during adolescence and early adulthood; the brain areas that govern capabilities for risk-reward assessment and impulse control are still developing well into the early 20s.4,5

State legislators have enacted several types of laws aimed at deterring easy access to firearms by youth and young adults. For example, state policies promoting safe firearm storage, such as Child Access Prevention Laws, have demonstrated associations with reductions in suicides and unintentional shootings by children and youth.6,7,8 Legislating firearms, however, is a logistically complex and politically contentious undertaking. Effects of youth-focused firearm laws may be dulled by the high prevalence of gun ownership in the United States and the ambient availability of firearms in many households.9 Laws limiting the availability of firearms for sale to young adults have been shown to be associated with decreased gun carrying by youths.10 The effects of many state firearm laws, ostensibly intended to prevent lethal violence using firearms, have not been studied. Evaluating the effect of minimum age laws on firearm homicide perpetrated by young adults can provide legislators with evidence to make informed policy decisions.

Handguns, compared with long guns, are much more likely to be used in crime owing to their lower price and easier concealability, and thus are more regulated than long guns.11 Although the federal Gun Control Act of 1968 established a minimum age of 21 years to purchase handguns from licensed dealers, the law did not extend to unlicensed dealers. This changed in 1994, when the federal government established a minimum age of 18 years to purchase a handgun from an unlicensed dealer and to possess a handgun. Since 1994, 5 states have enacted laws that raised the minimum age to purchase a handgun from all sources, including private transfers, to 21 years and/or raised the minimum age to possess a handgun to 21 years. To our knowledge, however, the effect of these minimum age laws on youth homicide perpetration is unknown. Our objective was to evaluate whether state laws that raised the minimum age to purchase and/or possess a handgun to 21 years were associated with lower rates of firearm homicide perpetrated by young adults aged 18 to 20 years.

Methods

Data and Sample

This study used deidentified, publicly available data and so does not meet the definition of human subjects research; therefore it was deemed exempt from institutional review board review and informed consent. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

We conducted a quasi-experimental cohort study using a difference-in-differences (DiD) approach. We used annual, state-level data to evaluate whether implementation of stricter minimum age laws to purchase and/or possess a handgun was associated with a reduction in the rate of firearm homicide perpetrated by young adults aged 18 to 20 years.12 We restricted our study to this age group because this is the population affected by the stricter minimum age laws. Given the 1994 changes to federal minimum age laws, we restricted our analysis to January 1, 1995, through December 31, 2017. The “untreated” group of states for comparison consisted of all US states that did not implement stricter minimum age laws for purchase/possession of handguns after 1994. We excluded 12 states that had stricter minimum age laws in place before the 1994 changes in federal law. Because our objective was to investigate the association between the implementation of a more stringent state minimum age law and firearm homicides, states that already had stricter policies in place did not represent the suitable counterfactual for our exposure (ie, nonimplementation of stricter minimum age laws).

Exposure and Outcome

Our exposure of interest was the implementation of a state law stricter than those established by the federal government with respect to the minimum age needed to purchase and/or possess a handgun. To identify states with stricter minimum age laws, we reviewed firearm law databases compiled by the RAND Corporation13 and Siegel et al.14 When there was not congruence between these 2 data sources, a research assistant (A.G.B.) who was not involved in data analysis adjudicated through original policy research of applicable state statutes. Based on our legal research of state laws, we identified 4 states that implemented both stricter purchase and possession laws from 1995 through 2017: Massachusetts (1998), Maryland (1996), New Jersey (2001), and New York (2000). In addition, Wyoming increased the minimum age to purchase a handgun from any dealer from 18 to 21 years of age in 2010, although it did not also increase the minimum age to possess a handgun.

We created a dummy variable set equal to 1 for years in which the stricter minimum age laws were in effect for at least 6 months and 0 for all other years. In a sensitivity analysis, we allowed for a 2-year washout period after implementation of state laws by setting our dummy variable to 0 for the 2 years after implementation of the law.

Our outcome of interest was annual state totals of homicide perpetrated by young adults aged 18 to 20 years. We obtained data on the number of homicides perpetrated by young adults aged 18 to 20 years from the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Supplementary Homicide Reports (SHR). The SHR is one of the main sources of data on homicide offenders in the United States, although it is not without limitations.15 First, homicide reports are voluntarily submitted by law enforcement agencies, and not all jurisdictions report their data each year. Historically, SHR has captured slightly fewer homicides than those collected in national administrative data abstracted from death certificates; however, the difference between data sources remains stable over time and may be accounted for through slightly mismatched definitions of homicide (eg, inclusion of manslaughter) and coverage of jurisdiction.16 In addition, data on offender characteristics are only available for solved homicides. During our study period, only 68.6% of homicide records included offender age. Despite these limitations, the SHR is widely used in firearm research.17

Covariates

We obtained annual data for several state-level variables identified as being plausible confounders of the association between minimum age laws and firearm homicide. We collected data on per capita alcohol consumption from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism18 and the proportions of the population that were male, Black, and Hispanic from Census Bridged Race Population estimates.19 The Census Bureau does not calculate annual estimates of the proportion of the population that lives in rural areas, so we used linear interpolation to fill in data between census years.20 We obtained annual poverty rates from National Welfare Data compiled by the University of Kentucky Center for Poverty Research21 and annual unemployment data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.22 We used data from the Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System to calculate the proportion of suicides that are firearm suicides, which is a widely accepted proxy for firearm ownership.23 Finally, data on other state firearm policies were obtained from Siegel’s State Firearms Laws Database.24 Specifically, for each state-year, we included indicator variables for state firearm laws that may have affected the homicide rate, including minimum age of 18 years to purchase a long gun, a minimum age of 16 years to possess a long gun, minimum age of 18 years to possess a long gun, exceptions to minimum age laws for hunting, universal background checks to purchase a handgun, and background checks through universal permit requirements for handgun sales. We elected to include specific firearm laws as covariates, rather than an overall rating of the state firearm law environment, to ensure that we controlled for differences in state policies that may affect firearm acquisition by young adults aged 18 to 20 years.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed from November 7, 2019, to June 23, 2020. In this DiD analysis, we compared firearm homicides perpetrated by young adults aged 18 to 20 years between states that implemented stricter minimum age laws and those that did not. Difference-in-differences analyses are a common tool for evaluation of policy.25,26 We calculated annual and summary (before and after implementation) crude homicide rates for each state included in our primary analysis. Firearm and nonfirearm homicide rates were calculated and modeled as separate outcomes.

For our primary analysis, we used negative binomial regression models to model the difference in the change in annual state total of homicides perpetrated by young adults aged 18 to 20 years between states that did and did not implement stricter minimum age laws after 1994. To estimate incidence rate ratios (IRRs), we included annual estimates for state population (all ages) as an offset term.27 We conducted similar analyses using linear regression models to model absolute changes in the rate of homicide perpetrated by young adults aged 18 to 20 years.

Consistent with other evaluations of public policy using a DiD approach, we included fixed effects for state and year in all models.26 Clustering of observations over time by state was accounted for using robust Huber-White sandwich standard errors.28 We further included the following covariates in the models: proportions of the state population that were male, Black, and Hispanic and lived in rural areas; the poverty rate; the unemployment rate; per capita alcohol consumption; and our proxy for firearm ownership.23 We also included a set of indicator covariates for state firearm laws that may affect the rates of homicides perpetrated by young adults aged 18 to 20 years as described above. We conducted all analyses in Stata, version 15.1 (StataCorp LLC) and used RStudio, version 1.2.5042 (RStudio, Inc) to create the Figure.

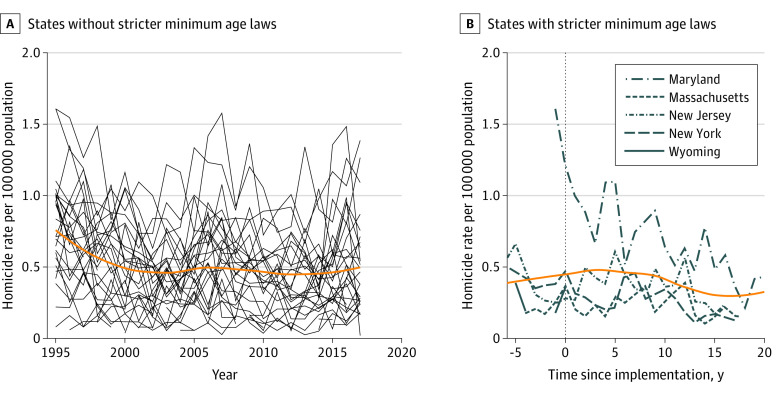

Figure. Crude Rates of Firearm Homicides Perpetrated by Youth Aged 18 to 20 Years by State.

Thirty-two states were included in the comparator group of states that did not enact stricter minimum age laws after the federal statute of 1994 (A). Five states enacted stricter laws (Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Wyoming) (B). The orange line indicates LOESS smoother. Wyoming line has discontinuity owing to missing data in some years.

Results

During the study period, 275 171 firearm homicides occurred nationally (67.9% of all homicides), of which 35 960 (13.1%) were perpetrated by young adults aged 18 to 20 years. The national rate of firearm homicides perpetrated by young adults declined during our study period from 0.87 per 100 000 population in 1995 to 0.44 per 100 000 population in 2017. Trends in firearm homicide committed by young adults in the intervention and untreated states are shown in the Figure.

In states that implemented stricter minimum age laws, the mean rate of firearm homicide perpetrated by young adults in the years before implementation ranged from 0.21 per 100 000 population in Massachusetts to 1.74 per 100 000 population in Maryland. Although the means were slightly lower, these rates were similar to rates of firearm homicide perpetrated by young adults in states that did not implement stricter purchase or possession laws over the study period (ranging from 0.11 per 100 000 population in Maine to 1.11 per 100 000 population in Louisiana). After implementation, the young adult–perpetrated firearm homicide rates in each state ranged from 0.23 per 100 000 population in Massachusetts to 0.67 per 100 000 population in Maryland (Table 1).

Table 1. Crude Rates of Firearm-Related Homicide per 100 000 Population Perpetrated by Youth Aged 18 to 20 Years Among States With and Without Minimum Age Laws for Purchase and Possession of Handguns Stricter Than the Federal Lawa.

| State | No stricter purchase and possession laws | Stricter purchase and possession laws | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State-years | No. of firearm-related homicides | Total population | Firearm homicide rate per 100 000 population | State-years | No. of firearm-related homicides | Total population | Firearm homicide rate per 100 000 population | |

| Alabama | 22 | 567 | 101 848 236 | 0.56 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Alaska | 22 | 84 | 14 835 898 | 0.57 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Arizona | 23 | 568 | 134 950 758 | 0.42 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Arkansas | 23 | 487 | 64 473 823 | 0.76 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Colorado | 23 | 424 | 109 066 841 | 0.39 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Florida | 23 | 1470 | 409 413 498 | 0.36 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Idaho | 18 | 57 | 25 620 926 | 0.22 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Indiana | 23 | 642 | 145 044 584 | 0.44 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Kansas | 18 | 224 | 50 638 019 | 0.44 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Kentucky | 23 | 308 | 96 740 527 | 0.32 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Louisiana | 23 | 1157 | 103 805 492 | 1.11 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Maine | 13 | 18 | 16 832 328 | 0.11 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Maryland | 1 | 88 | 5 070 033 | 1.74 | 22 | 825 | 123 598 986 | 0.67 |

| Massachusetts | 4 | 51 | 24 819 097 | 0.21 | 19 | 289 | 124 365 141 | 0.23 |

| Michigan | 23 | 1595 | 228 342 528 | 0.70 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Minnesota | 23 | 300 | 118 390 918 | 0.25 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Mississippi | 23 | 489 | 66 723 038 | 0.73 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Montana | 13 | 21 | 12 452 917 | 0.17 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Nebraska | 19 | 69 | 34 013 015 | 0.20 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Nevada | 23 | 265 | 55 096 738 | 0.48 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| New Hampshire | 7 | 9 | 8 886 275 | 0.10 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| New Jersey | 6 | 205 | 49 529 277 | 0.41 | 17 | 555 | 148 571 467 | 0.37 |

| New Mexico | 23 | 237 | 44 762 716 | 0.53 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| New York | 5 | 373 | 93 407 741 | 0.40 | 18 | 911 | 348 110 237 | 0.26 |

| North Carolina | 23 | 1381 | 204 572 241 | 0.68 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| North Dakota | 4 | 4 | 2 804 931 | 0.14 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Oklahoma | 23 | 5160 | 83 334 714 | 0.62 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Oregon | 23 | 114 | 84 344 244 | 0.14 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Pennsylvania | 23 | 1501 | 287 807 625 | 0.52 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| South Dakota | 8 | 17 | 6 431 200 | 0.26 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Tennessee | 23 | 1416 | 139 452 453 | 1.02 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Texas | 23 | 3186 | 540 407 202 | 0.59 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Utah | 23 | 188 | 58 560 121 | 0.32 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Vermont | 4 | 8 | 2 436 718 | 0.33 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Virginia | 23 | 1377 | 175 460 286 | 0.78 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| West Virginia | 21 | 97 | 38 424 793 | 0.25 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Wisconsin | 22 | 685 | 122 208 212 | 0.56 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Wyoming | 5 | 7 | 2 585 288 | 0.27 | 2 | 5 | 1 146 606 | 0.44 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

All states with less than 23 total years of data had missing firearm homicide data in select years. We excluded 12 states that had stricter minimum age laws in place before the 1994 changes in federal law because they did not represent the suitable counterfactual for our exposure (ie, nonimplementation of stricter minimum age laws).

Implementation of stricter minimum age laws to purchase and/or possess a handgun was not associated with a significant change in the rate of homicides perpetrated by young adults aged 18 to 20 years (crude IRR, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.86-1.40). After controlling for state-level variables, results were null for both firearm-related (adjusted IRR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.89-1.45) and non–firearm-related homicide (adjusted IRR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.94-1.22) (Table 2). Incidence rate differences produced from linear regression models were similar (eTable in the Supplement).

Table 2. Association of Minimum Age Laws With Homicides Perpetrated by Young Adults Aged 18 to 20 Years.

| Model | IRR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Firearm-related homicide | Non–firearm-related homicide | |

| Crude | 1.10 (0.86-1.40) | 1.05 (0.88-1.25) |

| Adjusteda | 1.14 (0.89-1.45) | 1.07 (0.94-1.22) |

Abbreviation: IRR, incidence rate ratio.

Adjusted for proportion of the population that is male, Black, Hispanic, lives in rural areas, and is unemployed; the poverty rate; the ratio of adult firearm suicide to suicide; per capita alcohol consumption among persons 14 years and older; law establishing minimum age of 18 years to purchase a long gun; law requiring universal background check to purchase a handgun; and law requiring a universal background check to obtain a permit to purchase a handgun.

When we repeated the adjusted analysis without Wyoming (because it was the only state to not also increase the age for handgun possession to 21 years), our results were similar (IRR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.88-1.44). Results were also similar in a sensitivity analysis with a 2-year lag or washout period after the state law went into effect (adjusted IRR for firearm-related homicide, 1.11 [95% CI, 0.83-1.47]; adjusted IRR for non–firearm-related homicide, 1.08 [95% CI, 0.95-1.22]) (Table 3).

Table 3. Sensitivity Analysis With 2-Year Washouta.

| Model | IRR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Firearm-related homicide | Non–firearm-related homicide | |

| Crude | 1.07 (0.81-1.41) | 1.06 (0.89-1.27) |

| Adjustedb | 1.11 (0.83-1.47) | 1.08 (0.95-1.22) |

Abbreviation: IRR, incidence rate ratio.

Includes year of implementation and 1 year after.

Adjusted for proportion of the population that is male, Black, Hispanic, lives in rural areas, and is unemployed; the poverty rate; the ratio of adult firearm suicide to suicide; per capita alcohol consumption among persons 14 years and older; law establishing minimum age of 18 years to purchase a long gun; law requiring universal background check to purchase a handgun; and law requiring a universal background check to obtain a permit to purchase a handgun.

Discussion

We found that implementation of stricter minimum age laws was not associated with a significant change in the rate of firearm homicides perpetrated by young adults aged 18 to 20 years. This finding suggests that state-level minimum age laws for handgun purchase and/or possession that are more comprehensive than the federal laws are not likely to significantly prevent firearm homicide perpetration by the affected age group.

There are several possible reasons why we did not observe an association of minimum age laws with lethal firearm violence perpetrated by young adults aged 18 to 20 years. First, this population may not be acquiring guns used in crimes through formal purchase. Young adults younger than 21 years may have relatively easy access to guns through informal channels. A study of youth with self-inflicted firearm injuries showed that most of the time, the firearm was taken from a household member.29 In a study of gun acquisitions among delinquent youth aged 14 to 18 years, all respondents who possessed firearms acquired their initial gun from someone they knew, and 83% paid less than $100 for it.30 Although we specifically studied minimum age laws that apply to all dealers, including private transfers, preventing illegal transfers of firearms to persons prohibited from owning a gun, including youth, is difficult, and a diverse array of options exists for illegal acquisition of firearms.31,32 Because most handguns used in crimes by young adults aged 18 to 20 years are acquired from sources unlikely to be affected by statutory restrictions, it is not surprising that we found no association between state laws and homicide perpetration in this age group.

Second, firearm dealers may be liable to sell handguns in a “straw purchase,” a situation in which someone purchases a gun on behalf of someone who is prohibited from owning firearms. Firearm dealers shoulder the burden of compliance with minimum age laws to determine whether a potential buyer is of legal age, and they have broad leeway in the identification of possible straw purchases, especially when enforcement is lax.33 Some firearm dealers are more likely than others to be the most recent source of diverted firearms, through illegal sales or allowing straw purchasing.11 Most guns (57.5%) recovered by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) were traced to first purchase from a small minority (1.2%) of federally licensed firearm dealers.34 Moreover, a national telephone survey asked firearm dealers if they would be willing to sell a gun that the interviewer stated would be given to someone else and found that more than half were willing to sell a firearm to the potential customer, even when it would be illegal to do so.33

Third, state laws may have incomplete enforcement, particularly in smaller states or in counties that lie along state borders. Stringent gun laws in one state may be easily circumvented by acquiring firearms in neighboring states with looser gun laws. Some evidence suggests that county-level homicide rates are affected by the strictness of gun laws in neighboring states.35 There are also well-known interstate illegal trafficking routes for guns used to commit crime, including the “iron pipeline” that runs along Interstate-95 carrying guns from Southern states with less restrictive gun laws to New England.36 Indeed, only 23% of firearms recovered from homicides in New Jersey was traced by the ATF to initial purchase in that state.37 Juveniles (aged <18 years) and young adults (aged 18-24 years) are involved in 42% of firearms trafficking investigations by the ATF, underscoring the fact that many delinquent youth and young adults acquire firearms from informal transfers instead of traditional retail sales.32,34,38

Our study is in line with the few studies that have examined the effects of minimum age laws on firearm homicides and suicides among older adolescents and young adults.8,39 Rosengart et al39 found no significant evidence that minimum age laws decreased youth mortality from suicide or homicide from 1979 to 1998. In 2004, Webster et al8 studied the effect of state-level changes in minimum age laws on suicide rates among youth aged 14 to 20 years using data from 1976 to 2001, and their findings were mixed. Only 3 states increased the minimum age for handgun possession to 21 years during this study period; when restricting to these states, the authors found no significant association between that policy and suicides among those aged 18 to 20 years.8 However, among the 21 states that increased the minimum purchase age to 21 years, Webster et al8 found a 9.0% decrease in firearm suicide among youth aged 18 to 20 years.

Limitations

Our study is subject to some limitations. As an ecologic study, it could not measure individual changes in behavior in response to the laws. Generalizability may be limited because Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, and New Jersey have some of the most stringent gun laws in the United States, whereas Wyoming is one of the least strict states for firearm regulations.40 However, because our DiD analysis studied within-state change, time-invariant factors should not confound our findings. Our findings may be also subject to information bias owing to underreporting of homicides in states with fewer resources to solve homicides. The SHR contains only information about homicide offenders when the offense is cleared or the offender is identified. According to an analysis of factors related to clearance rates of homicides in the United States, the age of those killed (grouped as 13-58 years) was associated with decreased likelihood of being solved.41 The same analysis found homicides involving a noncontact weapon, such as a handgun, were also less likely to be cleared than homicides involving contact weapons (such as a knife).41 In Wyoming, where stricter minimum age laws were implemented for handgun purchase but not handgun possession, there was at least 1 homicide with a known offender age for only 7 years during the study period (compared with ≥20 years of data for other states in the intervention group). Additional limitations include the potential for residual confounding from using a proxy measure for gun ownership, as well as covariates derived from data that are not collected annually (ie, population estimates).

Conclusion

The findings of this study suggest that implementation of state-level laws that increase the minimum age to purchase and/or possess a handgun beyond the minimum age imposed by the federal government may not be effective in their intent to decrease firearm homicide, and the limitations of these laws should be understood by policy makers. Future research should explore further the informal channels through which youth and young adults acquire guns, and policy makers should explore more effective enforcement strategies. Policies limiting firearm access through informal channels may have a greater effect.

eTable. Incidence Rate Differences for the Association of Minimum Age Laws With Homicides Perpetrated by Youth Aged 18 to 20 Years

References

- 1.US Census Bureau National population by characteristics: 2010-2019. Revised June 17, 2020. Accessed May 19, 2020. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-national-detail.html

- 2.Centers for Disease Control WISQARS (Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System). Reviewed July 1, 2020. Accessed May 19, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html

- 3.Kaplan J. Jacob Kaplan’s concatenated files: Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) program data: supplementary homicide reports, 1976-2017. Modified October 10, 2018. Accessed May 19, 2019. https://www.openicpsr.org/openicpsr/project/100699/version/V7/view

- 4.Arain M, Haque M, Johal L, et al. Maturation of the adolescent brain. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:449-461. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S39776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinberg L. Risk taking in adolescence. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2007;16(2):55-59. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00475.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rivara FP. Youth suicide and access to guns. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(5):429-430. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azad HA, Monuteaux MC, Rees CA, et al. Child access prevention firearm laws and firearm fatalities among children aged 0 to 14 years, 1991-2016. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(5):1-8. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.6227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Webster DW, Vernick JS, Zeoli AM, Manganello JA. Association between youth-focused firearm laws and youth suicides. JAMA. 2004;292(5):594-601. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.5.594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xuan Z, Hemenway D. State gun law environment and youth gun carrying in the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(11):1024-1031. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.2116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Timsina LR, Qiao N, Mongalo AC, Vetor AN, Carroll AE, Bell TM. National instant criminal background check and youth gun carrying. Pediatrics. 2020;145(1):e20191071. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koper CS. Crime gun risk factors: buyer, seller, firearm, and transaction characteristics associated with gun trafficking and criminal gun use. J Quant Criminol. 2014;30(2):285-315. doi: 10.1007/s10940-013-9204-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dimick JB, Ryan AM. Methods for evaluating changes in health care policy: the difference-in-differences approach. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2401-2402. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.16153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cherney S, Morral A, Schell T, Smucker S. RAND State Firearm Law Database. RAND Corporation; 2019. Updated April 15, 2020. Accessed December 19, 2019. https://www.rand.org/pubs/tools/TL283-1.html doi: 10.7249/TL283-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siegel M, Pahn M, Xuan Z, et al. Firearm-related laws in all 50 US states, 1991-2016. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(7):1122-1129. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox JA. Missing data problems in the SHR: imputing offender and relationship characteristics. Homicide Stud. 2004;8(3):214-254. doi: 10.1177/1088767904265592 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bureau of Justice Statistics The nation’s two measures of homicide. Published July 2014. Accessed May 20, 2020. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ntmh.pdf

- 17.Zeoli AM, McCourt A, Buggs S, Frattaroli S, Lilley D, Webster DW. Analysis of the strength of legal firearms restrictions for perpetrators of domestic violence and their associations with intimate partner homicide. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(11):2365-2371. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwy174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haughwout SP, Slater ME Apparent per capita alcohol consumption: national, state, and regional trends, 1977-2016. Published April 2018. Accessed November 9, 2019. https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/surveillance110/CONS16.htm

- 19.US Census Bureau US Census populations with bridged race categories. Reviewed June 20, 2019. Accessed November 9, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/bridged_race.htm

- 20.US Census Bureau American Community Survey Data. Revised September 26, 2019. Accessed November 9, 2019. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/data.html

- 21.University of Kentucky Center for Poverty Research National Welfare data, 1980-2018. Updated June 5, 2019. Accessed November 9, 2019. http://ukcpr.org/resources/national-welfare-data

- 22.Bureau of Labor Statistics Local area unemployment statistics home page. Updated February 28, 2019. Accessed November 9, 2019. https://www.bls.gov/lau/

- 23.Azrael D, Cook PJ, Miller M. State and local prevalence of firearms ownership measurement, structure, and trends. J Quant Criminol. 2004;20(1):43-62. doi: 10.1023/B:JOQC.0000016699.11995.c7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siegel M. State firearms laws database. Updated 2020. Accessed July 12, 2019. http://statefirearmlaws.org/

- 25.French B, Heagerty PJ. Analysis of longitudinal data to evaluate a policy change. Stat Med. 2008;27(24):5005-5025. doi: 10.1002/sim.3340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wing C, Simon K, Bello-Gomez RA. Designing difference in difference studies: best practices for public health policy research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39:453-469. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics Reviewed July 16, 2020. Accessed January 29, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/index.htm

- 28.Primo DM, Jacobsmeier ML, Milyo J. Estimating the impact of state policies and institutions with mixed-level data. State Polit Policy Q. 2007;7(4):446-459. doi: 10.1177/153244000700700405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grossman DC, Reay DT, Baker SA. Self-inflicted and unintentional firearm injuries among children and adolescents: the source of the firearm. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(8):875-878. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.8.875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Webster DW, Freed LH, Frattaroli S, Wilson MH How delinquent youths acquire guns: initial versus most recent gun acquisitions. J Urban Health. 2002;79(1):60-69. doi: 10.1093/jurban/79.1.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Braga AA, Wintemute GJ, Pierce GL, Cook PJ, Ridgeway G. Interpreting the empirical evidence on illegal gun market dynamics. J Urban Health. 2012;89(5):779-793. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9681-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vittes KA, Vernick JS, Webster DW. Legal status and source of offenders’ firearms in states with the least stringent criteria for gun ownership. Inj Prev. 2013;19(1):26-31. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2011-040290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorenson SB, Vittes KA. Buying a handgun for someone else: firearm dealer willingness to sell. Inj Prev. 2003;9(2):147-150. doi: 10.1136/ip.9.2.147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco & Firearms Following the gun: enforcing federal laws against firearms traffickers. Published June 2000. Accessed January 28, 2020. http://everytown.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Following-the-Gun_Enforcing-Federal-Laws-Against-Firearms-Traffickers.pdf

- 35.Kaufman EJ, Morrison CN, Branas CC, Wiebe DJ. State firearm laws and interstate firearm deaths from homicide and suicide in the United States: a cross-sectional analysis of data by county. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(5):692-700. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yablon A, Nass D. Potential gun trafficking hubs revealed in ATF data Published October 24, 2019. Accessed May 20, 2020. https://www.thetrace.org/2019/10/gun-trafficking-hubs-atf-time-to-crime/

- 37.Collins T, Greenberg R, Siegel M, et al. State firearm laws and interstate transfer of guns in the USA, 2006-2016. J Urban Health. 2018;95(3):322-336. doi: 10.1007/s11524-018-0251-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Webster DW, Vernick JS, Bulzacchelli MT. Effects of state-level firearm seller accountability policies on firearm trafficking. J Urban Health. 2009;86(4):525-537. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9351-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosengart M, Cummings P, Nathens A, Heagerty P, Maier R, Rivara F. An evaluation of state firearm regulations and homicide and suicide death rates. Inj Prev. 2005;11(2):77-83. doi: 10.1136/ip.2004.007062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giffords Law Center Minimum age to purchase & possess. Updated November 2019. Accessed November 9, 2019. https://lawcenter.giffords.org/gun-laws/policy-areas/who-can-have-a-gun/minimum-age/

- 41.Roberts A. Predictors of homicide clearance by arrest: an event history analysis of NIBRS incidents. Homicide Stud. 2007;11(2):82-93. doi: 10.1177/1088767907300748 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Incidence Rate Differences for the Association of Minimum Age Laws With Homicides Perpetrated by Youth Aged 18 to 20 Years