Abstract

This cohort study reports outcomes of long-term follow-up in patients with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody–associated disorder.

Data on long-term outcomes of patients with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) immunoglobulin G (IgG)–associated disorder (MOGAD) are scarce.1,2 We report outcomes in a single-institution cohort with long-term follow-up.

Methods

Patient Ascertainment

We retrospectively identified 11 adult and 18 pediatric (onset age younger than 18 years) Mayo Clinic patients from January 1, 2000, through May 31, 2019, with (1) MOGAD clinical phenotype3; (2) MOG-IgG 1 seropositivity (median titer, 1:100; range, 1:20-1:1000; 8 of 13 serial samples persistently positive)3; and (3) 9 or more years’ follow-up from onset. The study was approved by the Mayo Foundation Institutional Review Board (IRB No. 08.006647). Written informed consent was provided by patients or parents.

Outcome Measures

The annualized relapse rate, Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score, ophthalmology evaluation (including visual acuity evaluation), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were assessed at last follow-up (S.L., M.B., J.J.C.). Persistent visual field defects were defined by confrontation testing or mean deviation greater than −3 dB on Humphrey testing, and funduscopic examination was used to assess for optic atrophy.

Results

Clinical Course and Disability

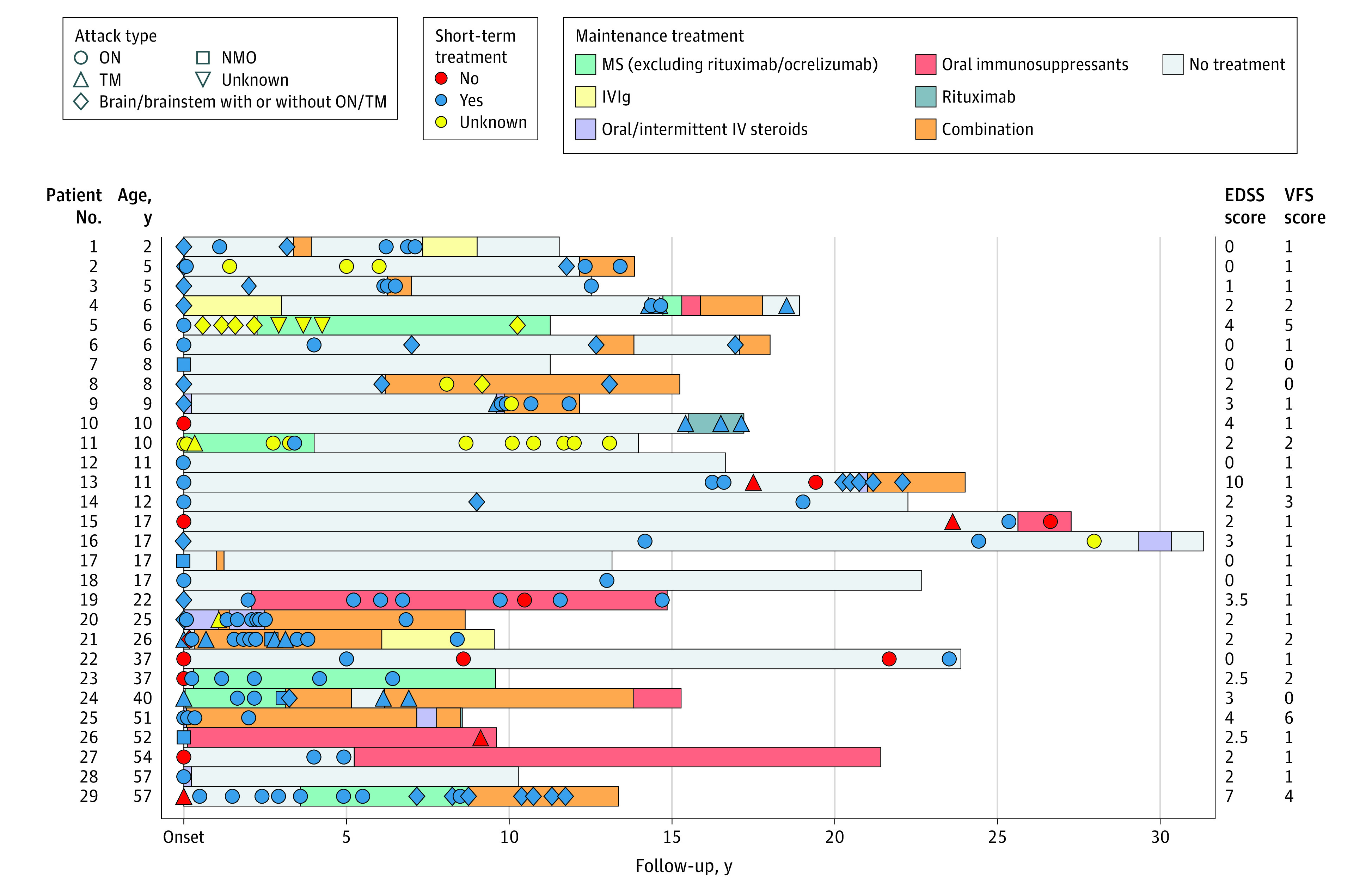

A total of 29 patients were included (Table, Figure). The temporal distribution and types of attacks (total attacks, 172; median [range] per patient, 5 [1-16]) and short-term and maintenance immunotherapy are illustrated in the Figure. The median (range) follow-up duration was 14 (9-31) years; 4 patients (14%) were monophasic. The median (range) annualized relapse rate was 0.33 (0.06-1.47). Eight of 15 (53%) with brain/spinal cord involvement required a wheelchair at initial attack nadir. The median (range) EDSS score at last follow-up was 2 (0-10), and 2 patients (7%) had an EDSS score of 6 or greater (1 died of MOGAD). No patients had secondary progression. Seven patients had residual bowel/bladder dysfunction. In patients with relapsing disease, the postrecovery median (range) EDSS score after the first attack was lower than at last follow-up (0 [0-3] vs 2 [0-10]; P = .001; paired t test).

Table. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics and Outcome of Patients With Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Immunoglobulin G–Associated Disorders.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cohort (N = 29) | Pediatric cohort (n = 18) | Adult cohort (n = 11) | ||

| Demographic data | ||||

| Female sex | 20 (69) | 15 (83) | 5 (45) | .048b |

| Age at onset, median (range), y | 17 (2-57) | 9.5 (2-17) | 40 (22-57) | NA |

| Initial clinical manifestationc | ||||

| Isolated TM | 3 (10) | 0 | 3 (27) | .045b |

| Isolated ON | 14 (48) | 9 (50) | 5 (46) | .81 |

| NMO (ON and TM) | 3 (10) | 2 (11) | 1 (9) | >.99 |

| Brain/brainstem with or without ON/TM | 9 (31) | 7 (39) | 2 (18) | .41 |

| Types of recurrent attacks in those relapsingc | ||||

| Isolated TM | 17 (12) | 10 (13) | 7 (10) | .85 |

| Isolated ON | 92 (64) | 43 (57) | 49 (73) | .09 |

| NMO (ON and TM) | 2 (1) | 0 | 2 (3) | .07 |

| Brain/brainstem with or without ON/TM | 29 (20) | 20 (26) | 9 (13) | .39 |

| Unknown | 3 (2) | 3 (4) | 0 | NA |

| Overall types of demyelinating attacks (initial manifestation or relapse)c | ||||

| Isolated TM | 20 (12) | 10 (11) | 10 (13) | .48 |

| Isolated ON | 106 (62) | 52 (55) | 54 (69) | .07 |

| NMO (ON and TM) | 5 (3) | 2 (2) | 3 (4) | .29 |

| Brain/brainstem with or without ON/TM | 38 (22) | 27 (29) | 11 (14) | .26 |

| Unknown | 3 (2) | 3 (3) | 0 | NA |

| No. of total demyelinating attacks (initial manifestation or relapse), median (range) | 5 (1-16) | 5 (1-12) | 6 (1-16) | .34 |

| No. of optic neuritis attacks, median (range) | 3 (0-11) | 2 (0-11) | 5 (0-8) | .07 |

| Bilateral optic nerve involvement | 24 (86) | 15 (88) | 9 (82) | .94 |

| LogMAR VA at last follow-up, median (range)d | 0 (0-1.7)d | 0 (0-0.6)d | 0 (0-1.7)d | .65 |

| Visual function system score at last follow-up, median (range) | 1 (0-6) | 1 (0-5) | 1 (0-6) | .45 |

| EDSS score at last follow-up | 2 (0-10) | 2 (0-10) | 2.5 (0-7) | .12 |

| Follow-up period, median (range), y | 14 (9-31) | 16 (11-31) | 10 (9-24) | .03b |

Abbreviations: EDSS, Expanded Disability Status Scale; MOGAD, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein immunoglobulin G–associated disorder; NA, not applicable; NMOSD, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder; ON, optic neuritis; TM, transverse myelitis; VA, visual acuity.

For categorical variables, P values are from χ2 test or Fisher exact test; for continuous variables, P values are from Wilcoxon rank sum test.

P value is significant.

Percentage reflects number of attacks divided by total attacks for each group. Percentages might not total 100 because of rounding.

Visual acuity scores converted to LogMAR for statistical comparison.

Figure. Temporal Distribution and Types of Attacks, Treatments Used, and Disability at Last Follow-up for Each Patient.

Short-term treatments were undertaken within 6 weeks and included 1 or more of corticosteroids (oral/intravenous [IV]), intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg), or plasma exchange. Maintenance treatments with multiple sclerosis (MS) medications included any current or prior approved MS medications except rituximab and ocrelizumab. Oral immunosuppressants included azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, or mycophenolate mofetil. Twenty-three patients received 1 or more maintenance attack-prevention treatments, including MS medications excluding rituximab/ocrelizumab (n = 6); IVIg (n = 3); oral/intermittent IV steroids (n = 5); rituximab (n = 1); oral immunosuppressants (n = 6); or a combination (n = 14). Of 14 patients who received combination treatment, the combinations included steroids and oral immunosuppressant, 13; steroids and rituximab, 5; steroids and IVIg, 4; rituximab and oral immunosuppressant, 1; and steroids and plasma exchange, 1. Triple combinations were also used: steroids, rituximab, and IVIg, 2; steroids, rituximab, and oral immunosuppressant, 1 (7%). EDSS indicates Expanded Disability Status Scale; NMO, neuromyelitis optica; ON, optic neuritis; TM, transverse myelitis; VFS, visual functional system.

Visual Outcomes

Optic neuritis occurred in 28 patients (97%; multiple episodes, 21; single episode, 7) (Figure, Table). At last follow-up, the median (range) visual acuity was 20/20 (20/20 to count fingers), and 26 of 29 patients (90%) had visual acuity of 20/40 or better bilaterally. Persistent visual field deficit occurred in 8 of 26 patients (31%), and optic atrophy was noted in 24 of 25 patients (96%; 8 with unilateral and 16 with bilateral atrophy).

MRI Findings

Follow-up brain MRI (median [range] time from onset, 6 [1-11] years) was available in 25 patients and revealed no residual demyelination in 18 patients (72%) and residual demyelinating T2 hyperintensities in 7 patients (28%; 3 with atrophy). All 6 follow-up spine MRI scans were normal.

Discussion

We found that most patients with MOGAD had a favorable long-term outcome without secondary progression despite frequent relapses, differing from that reported with multiple sclerosis (MS) and aquaporin-4–IgG neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSDs).

Our finding of just 7% having an EDSS score of 6 or greater and 7% unilaterally blind or worse after a median of 14 years of follow-up is similar to outcomes in previous studies with shorter follow-up.1,2,4 While some long-term deficit was accumulated from the presenting attack (similar to prior reports),1 additional attack-related EDSS score worsening in most patients suggests that attack prevention may be associated with lower long-term disability in relapsing MOGAD. Disability is less than with aquaporin-4–IgG NMOSD, with 65% being unilaterally blind or worse and 30% having an EDSS score of 6 or greater after a median of 8.3 years in a prior study.5 These contrasting outcomes support biomarker-based over syndromic-based diagnostic criteria, as NMOSD prognosis with MOG IgG differs markedly from prognosis with aquaporin-4 IgG.

A normal MRI (brain/spine) despite multiple radiologically confirmed relapses favors MOGAD over MS where residual T2 lesions are almost universal. No patients with MOGAD developed secondary progression, and a previous study of 200 patients with progressive MS found no MOG IgG seropositives,6 but younger age and frequent immunosuppressant use in this study could be associated with longer time to progression. Thus, more studies with longer follow-up are needed.

Our limitations include risk of acquisition bias from irregular follow-up, overrepresentation of severe cases from referral bias, and underrepresentation of monophasic or milder cases less likely to undergo follow-up. Nonetheless, the inclusion of additional patients with milder disease would support our conclusion that outcomes are good.

References

- 1.Jurynczyk M, Messina S, Woodhall MR, et al. . Clinical presentation and prognosis in MOG-antibody disease: a UK study. Brain. 2017;140(12):3128-3138. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cobo-Calvo A, Ruiz A, Maillart E, et al. ; OFSEP and NOMADMUS Study Group . Clinical spectrum and prognostic value of CNS MOG autoimmunity in adults: the MOGADOR study. Neurology. 2018;90(21):e1858-e1869. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.López-Chiriboga AS, Majed M, Fryer J, et al. . Association of MOG-IgG serostatus with relapse after acute disseminated encephalomyelitis and proposed diagnostic criteria for MOG-IgG-associated disorders. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(11):1355-1363. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.1814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramanathan S, Mohammad S, Tantsis E, et al. ; Australasian and New Zealand MOG Study Group . Clinical course, therapeutic responses and outcomes in relapsing MOG antibody-associated demyelination. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018;89(2):127-137. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-316880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiao Y, Fryer JP, Lennon VA, et al. . Updated estimate of AQP4-IgG serostatus and disability outcome in neuromyelitis optica. Neurology. 2013;81(14):1197-1204. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a6cb5c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jarius S, Ruprecht K, Stellmann JP, et al. . MOG-IgG in primary and secondary chronic progressive multiple sclerosis: a multicenter study of 200 patients and review of the literature. J Neuroinflammation. 2018;15(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s12974-018-1108-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]