Abstract

Background

The drivers of the gap in advancement between men and women faculty in academic Infectious Diseases (ID) remain poorly understood. This study sought to identify key barriers to academic advancement among faculty in ID and offer policy suggestions to narrow this gap.

Methods

During the 2019 IDWeek, we conducted focus groups with women faculty members at all ranks and men Full Professors, then we administered a brief survey regarding work-related barriers to advancement to the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) membership. We report themes from the 4 focus group discussions that are most closely linked to policy changes and descriptive analyses of the complementary survey domains.

Results

Policy change suggestions fell into 3 major categories: (1) Policy changes for IDSA to implement; (2) Future IDWeek Program Recommendations; and (3) Policy Changes for IDSA to Endorse as Best Practices for ID Divisions. Among 790 faculty respondents, fewer women reported that their institutional promotion process was transparent and women Full Professors were significantly more likely to have been sponsored.

Conclusions

Sponsorship and informed advising about institutional promotions tracks may help to narrow the advancement gap. The Infectious Disease Society of America should consider ambitious policy changes within the society and setting expectations for best practices among ID divisions across the United States.

Keywords: achievement, advancement, gender differences, medical faculty

There is a growing evidence base regarding the large and persistent gaps in achievement and advancement between men and women faculty in academic medicine, including in Infectious Diseases (ID) [1–5]. In a recent study of 2016 academic ID physicians in the United States, as of 2014 there was a highly significant 8% adjusted disparity in the rate of advancement to full professorship among women compared to men after adjustment for key demographic and achievement-related metrics including age, sex, years since residency completion, publications, National Institutes of Health grants, and registered clinical trials [1]. Moreover, when analyzed by residency graduation cohort, these sex differences within academic ID remained stable over time [1]. These findings suggested a strong need to identify the underlying causes of these disparities and enact policies to mitigate these differences.

However, although these differences are increasingly well recognized, the barriers responsible for delayed advancement among women faculty compared with their male peers remain poorly understood. The literature to date has begun to explore possible factors that may affect advancement generally in academic medicine, including family leave policies, domestic responsibilities, and negotiation skills, but these studies are largely analyses of single factors and use study populations of faculty physicians from all specialties [6–13]. Given the differences within the field of ID and the need to identify and generate policies to mitigate this gap, we partnered with the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) to explore these questions within its membership [14–16].

The objectives of this study were to (1) identify key barriers to academic advancement overall and by gender among faculty in ID and (2) offer insights regarding proposed policy approaches to remedy the gender differences in advancement in ID. We used a mixed methods approach in which we conducted a series of focus group discussions with women faculty members of all faculty ranks and men faculty members at the rank of Full Professor and concurrently administered a brief quantitative survey regarding overarching work-related barriers to equitable advancement to the 2019 IDWeek attendees and IDSA membership at large. Both of these activities were undertaken with the support of the IDSA and as part of IDSA’s 2019 IDWeek Annual Meeting.

METHODS

Faculty Focus Groups at 2019 IDWeek Annual Meeting

We conducted 4 60-minute focus groups with faculty members in ID during IDWeek 2019. The participants were recruited through the IDSA using email invitations targeted to IDSA members registered to attend IDWeek. To best capture the perspectives of women ID faculty members from diverse backgrounds, we asked potential participants to share their academic affiliation and current academic rank. We then enrolled women from medical schools in each of the 4 geographic regions of the AAMC, from representative academic medical centers on US News and World Report’s 2019–20 Top 20 Best Hospitals Honor Roll and from centers not on the Honor Roll, from Pediatric and/or Adult ID Divisions, and from each level of faculty advancement (Instructor/Assistant, Associate, Full Professor). We assigned participants to focus groups based on their academic rank to have a session exclusively for instructors/assistant professors, one for associate professors, and a third session for full professors. We also conducted a fourth focus group with only men who were Full Professors at US academic medical centers to capture additional perspectives about barriers to advancement and solutions. We chose to organize these groups by rank to minimize social desirability bias across rank (ie, to allow for both junior and senior faculty members to speak freely about barriers to advancement).

A member of the study team facilitated each discussion using a semistructured interview guide consisting of open-ended questions and probes designed to generate discussion about perceived barriers to academic advancement and proposed policy solutions. Open-ended questions were chosen to minimize bias and allow for unanticipated themes to emerge. Focus group discussions explored a range of topics, including the impact of institutional promotions tracks and transparency regarding promotions metrics on the likelihood of advancement, effectiveness and structure of faculty advising about promotions, the role of sponsorship and mentorship, personal challenges affecting faculty promotions, and policy changes suggested by focus group participants to improve gender equity in academic advancement. Discussions were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service.

Infectious Disease Society of America-Sponsored Survey on Equity in Academic Advancement

We assessed work-related barriers to academic advancement using an anonymous web-based survey administered to academic faculty in ID. All ID faculty members were invited and encouraged to respond to the survey. The survey was advertised using IDSA-sponsored communications to IDWeek attendees and by email to members of this society at large between September 18, 2019 and November 8, 2019. In addition, members could complete surveys at computer stations positioned near the registration desk at IDWeek. The survey captured participants’ sociodemographic characteristics and sought to quantify work-related barriers to faculty advancement and achievement, building on prior research. Survey domains included faculty promotion track (research, clinician educator, or other) and a suite of questions about workplace atmosphere and policies related to advancement, including mentoring and sponsorship opportunities, parttime work history, transparency of promotion criteria, and presence of women in positions of leadership. For the purposes of this study, a “sponsor” was defined as a “highly placed individual within an organization who influences decisions regarding appointments to committees, promotions and awards and who advocates for you.”

Mixed Methods Data Analysis

In this this mixed methods study, our analytic approach was to identify and characterize major barriers to academic advancement and potential policies to address these barriers, by integrating the findings from our quantitative survey and qualitative focus group discussions. Our qualitative study explored diverse topics related to women’s experiences with promotion; in this manuscript, we present those themes that align with our survey domains or can directly inform policy recommendations for IDSA, given our overall goal of informing actionable policy changes. We also emphasize those findings that were reinforced in both the qualitative and quantitative arms of the study.

Qualitative data were analyzed using content analysis to summarize and highlight emergent themes [17]. We first used an inductive process to develop a topic codebook guided by our research objectives. We then applied codes to sections of raw data for all study transcripts. Thereafter, 2 members of the study team independently reviewed the coded transcripts to determine emerging themes and then together agreed upon final themes. We report the final themes most closely linked to policy change suggestions for narrowing the advancement gap between genders. For the survey data, we conducted descriptive analyses of survey domains that related to potential policy recommendations or that complemented and enriched our qualitative findings, namely, perceptions of transparency for the promotions process, experiences with sponsorship, and promotion track data. We calculated means and proportions overall and by rank and gender for these items and used standard statistical tests for comparisons as appropriate. All analyses were conducted in STATA version 15.1. The study was determined to be exempt by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Qualitative Focus Group Discussions

Fourteen Assistant Professors, 11 Associate Professors, and 12 Full Professors participated in the respective women faculty focus groups. There were 13 participants in the men Full Professor focus group. Each focus group contained participants from all 4 AAMC-defined regions and from hospitals both on and off the top 20 US News and World Report Honor Roll.

Focus group discussions generated numerous themes regarding barriers and facilitators to academic advancement of women in ID. The spectrum of emergent themes was broad and included difficulty balancing demands of family with career, the contribution of implicit and explicit forms of gender bias to delayed advancement, and differences between genders in negotiation strategies, among others. A summary of the main emergent themes from the focus group analysis are shown in Supplementary Table S1. For the narrow purposes of this report, we intentionally focus only on emergent themes most directly associated with practical policy change recommendations to IDSA that could be implemented by the society or in the workplace to address gender disparity in academic advancement. These 4 themes and representative quotes from the focus group discussions are presented in Table 1. The gender and level of advancement of the quoted participants are specified.

Table 1.

Emergent Themes From Focus Group Analysis and Representative Quotes

| Theme: Policy change must come from “the top” (people/organizations in positions of leadership/privilege) |

| WFP – At our institution we had a survey that demonstrated real feelings of gender discrimination. As a result the Board of Trustees now wants us to address it…because of the publicity we now have the authority to develop formal recommendations for dealing with gender inequity. AP – Part of the challenge is that we don’t have enough male sponsors who are willing to stick their necks out to be like “This is important to me too. I’m signing onto this.”…you have to have men saying the same thing loudly from their position of privilege if you’re going to make progress. MFP – You can gain strength from enlisting other divisions who are facing the same challenges. So we went to our department and said, this is an issue for us and the department created a task force that is multi-divisional |

| Theme: Advising and transparency about promotions criteria by objective/expert advisors is crucial |

| ACP – It’s a problem if the person you’re going to talk to doesn’t understand promotions…I know promotions better than my section Chief...just because they’re in a position of leadership doesn’t mean they know… WFP – At our institution we’re assigning all junior faculty a mentor, not their research mentor, but a career mentor to meet with twice a year. Look at your CV…This is the track you’re on. What do you need to do? Someone outside of the division Chief that they can get feedback from. |

| Theme: Sponsorship facilitates academic advancement |

| WFP – When I think about the times in my career where I had acceleration, it had to do with people who put themselves out for me, whether it was money or putting me up for something or writing me a letter—if we don’t look below and try to raise other people up, it’s likely not going to happen ACP – We’re mentored to death, but we don’t get sponsorship. So one of my faculty wants to be on a committee and I know who is on the committee. So I sent them an email and wrote everything this woman has done. And she got it! And that’s promoting our faculty. MFP – That’s a really important point about being an influencer. Basically if you’re in a position to promote or nominate your faculty, to really make an intentional effort to do it, just don’t let those opportunities pass. |

| Theme: Women in positions of leadership or at higher levels of advancement should help junior women |

| MFP – I hired an extremely prominent ID woman to be my essentially co-chair and we run the department together. And she is a wonderful mentor to all the young faculty. She’s more than willing to talk, even if I have my head up my ass, and I’ve been more than willing to listen because she’s usually right. AP – Having strong female leadership is really important…our division director is a woman...I know a lot of our associate and assistant professors are women and she’s been very good at putting people up for promotion and being proactive. |

Abbreviations: ACP, Associate Professor; AP, Assistant Professor; CV, CV, curriculum vitae; ID, Infectious Diseases; MFP, men Full Professor; WFP, women Full Professor.

Specific policy change suggestions linked to these themes and representative quotes proposed during focus group discussions are presented in Table 2. We report these policy change suggestions in 3 broad categories: (1) Policy Changes for IDSA to Implement, (2) Future IDWeek Program Recommendations, and (3) Policy Changes for IDSA to Endorse as Best Practices for ID Divisions. These categories recognize the society’s tremendous capacity to effect change through policy initiatives and ID week programming and also to set standards and influence conduct in US academic ID divisions.

Table 2.

Policy Change Suggestions for IDSA From Focus Group Analysis

| Policy Changes for IDSA to Implement | |

|---|---|

| Make nomination process for IDSA committee(s) membership standardized and open to all IDSA Committee chairs should write letters for junior members confirming “national recognition” to support promotion Increase women participation in IDSA Leadership Institute and support other leadership training programs for women Fund awards for early career women investigators at high risk for slowing productivity due to family responsibilities (eg, Claflin Award ecor.mgh.harvard.edu) Ensure gender equality of editorial boards at CID and JID Partner with executive search firms looking for leaders in academic medicine and recommend qualified women faculty Develop IDSA Professional Coaching/Advising program with trained senior faculty mentors to advocate for junior faculty | ACP: IDSA can make it a more transparent process…more women can be put forward, all that helps your CV MFP: When you see somebody contributing, send things back to their division chiefs that they can use to promote them because IDSA has that clout WFP: I would love to see IDSA sending every year at least one woman to ELAM (Executive Leadership in Academic Medicine). ACP: At my hospital they have a grant for women researchers with children…they recognize I have competing priorities and, instead of (making) me cover those up, they’re celebrating. WFP: I think the Associate Editors at the editorial board should represent the proportions of people submitting to them. MFP: The IDSA Leadership Institute should connect with search firms…recommend people who have come through the course. WFP: A way of pairing people with advocates…where people who signed up to be mentors were really senior…committed to this and would be trained a little bit too |

| Future IDWeek Program Recommendations | |

| Deliver specific gender equity education to all ID Division Chiefs so “critical actors” have information needed to effect change Achieve gender equity in IDWeek presenters, moderators and panel discussants Create named lectures for women leaders in ID Design gender bias symposia/workshops to encourage attendees of all genders and backgrounds | MFP: Mandate ID leaders to take courses on diversity, equity, gender gap because people might not be aware of the statistics MFP: A directive that came from the board that there had to be equal representation on panels at IDWeek…and it’s working so you need that kind of goal setting ACP: It’s always a guy lecture name. I’m thinking a lecture named after a woman where they spend the first 10 minutes saying how she advanced the field MFP: Yesterday at the gender gap symposium there were a lot of women but (only) four men…I was looking around the room thinking these women aren’t the people who need this |

| Policy Changes for IDSA to Endorse as Best Practices for Academic ID Divisions | |

| Structured reviews addressing action plan for faculty promotion should be conducted/documented at least annually Faculty advisors should be trained/supported to provide local institutional expertise in advancement tracks/metrics Faculty advisors should have no conflicts of interest; promotions advisors outside of ID division should be cultivated Women role models of successful academic advancement should be supported/trained as promotions advisors Standardized and adequate parental leave policies should be developed for birth and nonbirth parents Engage departments, boards, hospital leadership in policy change – change needs to come “from the top” | WFP: I review their years in rank and we talk specifically and I put a letter that summarizes the review, the promotion plan… WFP: We’re assigning all junior faculty a career mentor to meet with, look at your CV. This is the track you’re on. What do you need to do? ACP: My institution has a mentoring committee…it’s three people, all external to your division and their job is to advocate to your division chief for what (you) need for promotion AP: We have strong female leadership and one of their projects is to identify women who aren’t progressing—I got an email from a female mentor to set up a meeting to discuss promotion plans. MFP: We still don’t have a maternity leave policy. Women are free to take leave but they have to make up their RVUs or continue to churn out papers. AP: We have a Faculty Review Commission, independent of different departments, that did a promotion review that resulted in women being advanced ahead of schedule. |

Abbreviations: ACP, Associate Professor; AP, Assistant Professor; CID, Clinical Infectious Diseases; CV, curriculum vitae; ID, Infectious Diseases; IDSA, Infectious Disease Society of America; JID, Journal of Infectious Diseases; MFP, man Full Professor; WFP, woman Full Professor.

Quantitative Survey

Among 1028 survey respondents, 161 were excluded because they did not self-identify as academic faculty and 32 were part of a planned subanalysis of allied health professionals or pharmacists. This left a sample of 835 individuals, among whom 790 provided both a gender and a faculty rank and were thus retained in the final analytic dataset. Among these 790 participants, there were 322 men (40.7%), 458 women (58.0%), 8 individuals who preferred not to provide a gender, and 2 individuals who self-described their gender (1.3%). These 790 respondents represent 35% of the 2251 IDSA members who hold a medical degree and are academic faculty in ID. There were 47 Instructors (5.9%), 305 Assistant Professors (38.6%), 198 Associate Professors (25.1%), and 240 Full Professors (30.4%). Instructors and Assistant Professors were grouped in our analyses. Academic ID faculty from both Pediatric and Adult ID Divisions were invited to participate in the survey, although respondents were not asked to identify their training pathway. Table 3 summarizes the sample stratified by rank and gender, which was almost identical to the gender and rank distribution of academic ID physicians per the AAMC in 2014 except for slightly greater representation of women Full Professors. We conducted the descriptive analyses with those who did not provide a gender or preferred to self-describe (“Other”) grouped with men (shown) and separately, excluding these 10 participants, and found no difference in the results.

Table 3.

IDSA Equity in Advancement Survey Participants by Gender and Faculty Rank, 2019

| Rank | All (N = 790) | Men (N = 322) | Women (N = 458) | Other (N = 10) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assistant | 352 (44.5) | 113 (32.1) | 235 (66.8) | 4 (1.1) | <.001 |

| Associate | 198 (25.1) | 76 (38.4) | 121 (61.1) | 1 (0.5) | .547 |

| Full | 240 (30.4) | 133 (55.4) | 102 (42.5) | 5 (2.1) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: IDSA, Infectious Disease Society of America.

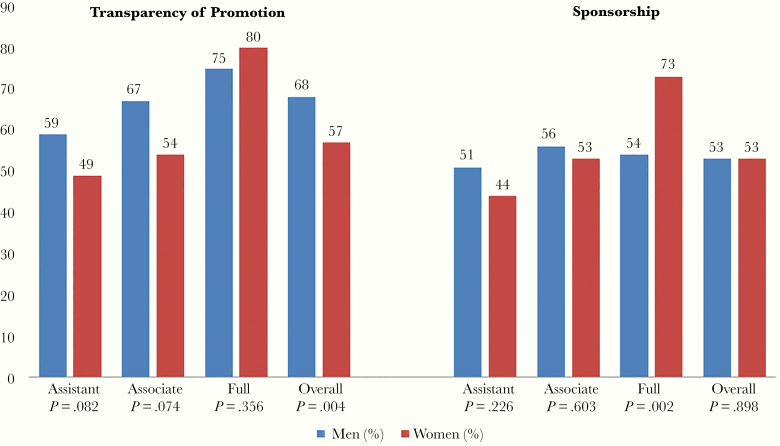

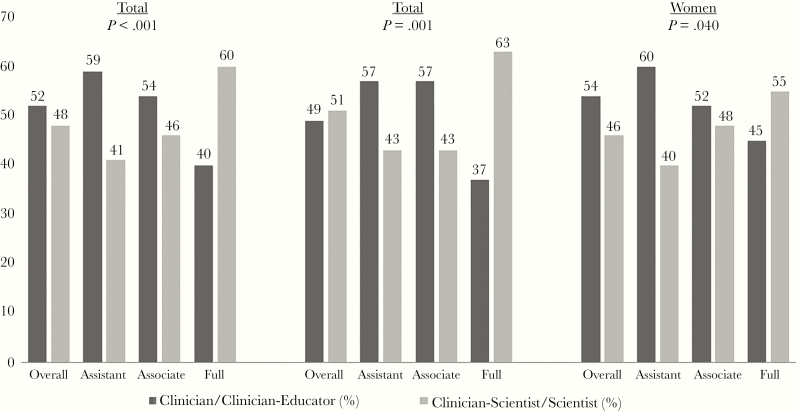

With the exception of women Full Professors, fewer women than men faculty reported that the promotion process in their institution was transparent (Figure 1). In terms of sponsorship, women Full Professors were significantly more likely to report that they had been sponsored compared with men Full Professors (men, 54%; women, 73%; P = .002) (Figure 1); there were no sex differences in sponsorship experiences for other academic ranks. With respect to differences in advancement by promotion track, those who identified as a Clinician or Clinician-Educator comprised a much larger proportion of Assistant (59%) and Associate Professors (54%) and a much smaller proportion of Full Professors (40%) than those who identified as a Clinician-Scientist or Scientist (Assistant, 41%; Associate, 46%; Full, 60%). This trend was statistically significant overall (P < .001) and within each gender (men, P = .001; women, P = .040), but it did not differ significantly between men and women (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Transparency of promotion criteria and sponsorship by faculty rank and gender among academic Infectious Disease physicians, 2019.

Figure 2.

Promotion track breakdown by faculty rank and gender among academic Infectious Disease physicians, 2019.

DISCUSSION

This study identified several perceived barriers to academic advancement in ID, at least 2 of which—a lack of transparency in the promotions process and receiving career sponsorship—seemed to affect women more than men. Our study also identified numerous policy recommendations that IDSA may consider in its efforts to foster greater equity in advancement. First, transparency of promotion, including the need for objective and expert advising in the communication of promotion requirements, emerged as important in both the qualitative and quantitative arms of the study and is a barrier to advancement that was previously highlighted in the literature regarding equity in academic ID [15]. Furthermore, poor transparency appeared to hinder women more than men, because women reported this barrier more consistently than their male colleagues. Focus group participants suggested several key policy recommendations regarding ways that IDSA may play a role in helping to overcome this barrier, including endorsing as a best practice that ID divisions cultivate trained, objective promotions advisors who can counsel faculty on promotion criteria from within and outside the division and, additionally, creating an IDSA Academic Advising Program of trained senior faculty mentors to provide expert guidance for faculty. This expert academic advising could be delivered via mentoring sessions at IDWeek or as part of a more longitudinal IDSA-sponsored program and would be of particular benefit to junior faculty from institutions lacking strong Faculty Development Offices or other internal divisional or institutional advising resources.

The importance of sponsorship in advancement was a second finding in this study that was strongly reflected in the focus groups and simultaneously endorsed by women Full Professors in the quantitative survey. A growing evidence base suggests that sponsorship opportunities are as—if not more—important than mentorship in determining professional achievement and advancement [18]. Focus group participants suggested several actions that IDSA may consider to facilitate sponsorship of its members. These included supporting increased representation of women in national leadership programs, such as the IDSA Leadership Institute, and on ID journal editorial boards, as well as partnering with professional search firms to ensure women are identified for possible leadership opportunities.

We also found that those in Clinician or Clinician-Educator faculty tracks comprised a much larger share of Assistant and Associate Professors, but that Clinician-Scientists and Scientists made up a much larger share of Full Professors. This could suggest lower rates or delays in promotions for the Clinician or Clinician-Educator faculty tracks. Although it is unclear whether our finding is due to a cohort effect among more recent generations of faculty or to other specific features of the promotion experience and criteria for our convenience sample, it is an important finding given the growing number of ID physicians who choose these career paths. This finding may also suggest that fewer fully advanced faculty members may have direct experiences with the Clinician or Clinician-Educator tracks or that promotions committees have valued the contribution of Clinician-Scientists and Scientists to a greater extent. This finding also relates closely to concerns about transparency of promotion criteria and the need for experienced senior faculty to provide informed and regularly scheduled promotions advice to junior faculty who declare academic careers in these areas. Moreover, although these were not gender-specific findings, in the long-term any disadvantage conferred by participation in the Clinician or Clinician-Educator tracks could work against efforts to decrease the gender gap in full professorship if more women enter into these tracks and if these tracks continue to be more opaque or less successful routes to promotion. One strategy to address this barrier would be for IDSA to generate and disseminate a structured guide with promotions criteria for those who identify as a Clinician or Clinician-Educator that could serve as an adaptable template for member institutions.

There were several limitations to this study. First, neither the qualitative focus groups nor the IDSA membership survey could exhaustively explore all possible barriers to advancement. In this report, we intentionally focused our assessments on work-related barriers, such as mentorship and sponsorship opportunities, career advancement tracks, and transparency of promotions advising because these work-related barriers are more likely to be immediately impacted by IDSA policy changes. There were several work-related factors, however, including the presence of women in positions of leadership other than division chief or department chair, that were not captured in this study. Moreover, although our focus group analysis identified rich themes relating to barriers beyond the workplace, such as the impact of gender bias, family demands, and partnerships on academic advancement, we were unable to fully explore these extremely important themes within the limits of this report. Second, our qualitative and quantitative samples were nonrepresentative and thus may not reflect the views of all members. However, the gender and rank distribution of survey participants closely mirrored the distribution of ID physicians in 2014, suggesting representativeness. Furthermore, for our qualitative study, the goal of our purposive sampling strategy was not representativeness, but rather to capture multiple perspectives by gender and rank, which we successfully achieved. Third, we were unable to explore the relationships between race, gender, and career outcomes in this study due to the limited sample size.

CONCLUSIONS

Addressing the gender gap in academic advancement in ID must be a priority for US academic medical centers. Enthusiastic sponsorship of junior women faculty by senior faculty advocates, along with informed, transparent advising about institutional promotions tracks, especially nontraditional tracks such as Clinician or Clinician-Educator, may help to narrow this gap, particularly if these issues affect women disproportionately. This study suggested that faculty in ID believe such efforts will be most effective if they come from “the top”. The IDSA should use its substantial power to effect ambitious policy changes, both within the society and by setting expectations for best practices at medical schools, hospitals, medicine departments, and ID divisions across the United States. In the words of 1 wise focus group participant, the time has come for IDSA to be an “influencer…to really make an intentional effort to do it…just don’t let those opportunities pass.”

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank all those who completed the survey and those who gave of their time so generously to participate in the focus groups. We also thank the staff at the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) for their guidance and support of this project at IDWeek.

Financial support. This work was funded by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. JMG is supported by grant number T32 AI007433 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The contents of this research are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

- 1. Manne-Goehler J, Kapoor N, Blumenthal DM, Stead W. Sex differences in achievement and faculty rank in academic infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 70:290–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marcelin JR, Manne-Goehler J, Silver JK. Supporting inclusion, diversity, access, and equity in the infectious disease workforce. J Infect Dis 2019; 220:50–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jena AB, Khullar D, Ho O, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in academic rank in US medical schools in 2014. JAMA 2015; 314:1149–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carr PL, Raj A, Kaplan SE, Terrin N, Breeze JL, Freund KM. Gender differences in academic medicine: retention, rank, and leadership comparisons from the national faculty survey. Acad Med 2018; 93:1694–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Stewart A, Sambuco D, DeCastro R, Ubel PA. Gender differences in the salaries of physician researchers. JAMA 2012; 307:2410–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jagsi R, Guancial EA, Worobey CC, et al. The “gender gap” in authorship of academic medical literature–a 35-year perspective. N Engl J Med 2006; 355:281–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Holliday E, Griffith KA, De Castro R, Stewart A, Ubel P, Jagsi R. Gender differences in resources and negotiation among highly motivated physician-scientists. J Gen Intern Med 2015; 30:401–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hechtman LA, Moore NP, Schulkey CE, et al. NIH funding longevity by gender. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018; 115:7943–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Boiko JR, Anderson AJM, Gordon RA. Representation of women among academic grand rounds speakers. JAMA Intern Med 2017; 177:722–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jolly S, Griffith KA, DeCastro R, Stewart A, Ubel P, Jagsi R. Gender differences in time spent on parenting and domestic responsibilities by high-achieving young physician-researchers. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160:344–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Manne-Goehler J, Freund KM, Raj A, et al. Evaluating the role of self-esteem on differential career outcomes by gender in academic medicine. Acad Med 2019. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rajasingham R. Female contribution to Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline publications. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 68:893–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Blumenthal DM, Olenski AR, Yeh RW, et al. Sex differences in faculty rank among academic cardiologists in the United States. Circulation 2017; 135:506–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Powderly WG. The importance of inclusion, diversity, and equity to the future of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. J Infect Dis 2019; 220:82–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Piggott DA, Cariaga-Lo L. Promoting inclusion, diversity, access, and equity through enhanced institutional culture and climate. J Infect Dis 2019; 220:74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sears CL, Del Rio C, Malani P. Inclusion, diversity, access, and equity: perspectives for infectious diseases. J Infect Dis 2019; 220:27–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Patton MQ. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory And Practice. 4th ed.Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc., 2015:xxi, 806. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ayyala MS, Skarupski K, Bodurtha JN, et al. Mentorship is not enough: exploring sponsorship and its role in career advancement in academic medicine. Acad Med 2019; 94:94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.