Abstract

PURPOSE:

Financial hardship is increasingly understood as a negative consequence of cancer and its treatment. As patients with cancer face financial challenges, they may be forced to make a trade-off between food and medical care. We characterized food insecurity and its relationship to treatment adherence in a population-based sample of cancer survivors.

METHODS:

Individuals 21 to 64 years old, diagnosed between 2008 and 2016 with stage I-III breast, colorectal, or prostate cancer were identified from the New Mexico Tumor Registry and invited to complete a survey, recalling their financial experience in the year before and the year after cancer diagnosis. Multivariable logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95%CIs.

RESULTS:

Among 394 cancer survivors, 229 (58%) were food secure in both the year before and the year after cancer diagnosis (persistently food secure), 38 (10%) were food secure in the year before and food insecure in the year after diagnosis (newly food insecure), and 101 (26%) were food insecure at both times (persistently food insecure). Newly food-insecure (OR, 2.82; 95% CI, 1.02 to 7.79) and persistently food-insecure (OR, 3.04; 95% CI,1.36 to 6.77) cancer survivors were considerably more likely to forgo, delay, or make changes to prescription medication than persistently food-secure survivors. In addition, compared with persistently food-secure cancer survivors, newly food-insecure (OR, 9.23; 95% CI, 2.90 to 29.3), and persistently food-insecure (OR, 9.93; 95% CI, 3.53 to 27.9) cancer survivors were substantially more likely to forgo, delay, or make changes to treatment other than prescription medication.

CONCLUSION:

New and persistent food insecurity are negatively associated with treatment adherence. Efforts to screen for and address food insecurity among individuals undergoing cancer treatment should be investigated as a strategy to reduce socioeconomic disparities in cancer outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Financial hardship associated with cancer and its treatment is reported by as many as half of all cancer survivors in the United States.1 To cope with lost income, out-of-pocket medical costs, and transportation costs, many cancer survivors make financial sacrifices. Zafar et al2 found 46% of cancer survivors reduced spending on basics like food and clothing. As cancer survivors and their families experience financial hardship, they may be forced to choose between food and recommended medical care. The balance between having enough healthy food to eat and obtaining medical care may be particularly tenuous for patients at greatest risk of financial hardship, including younger, minority, rural, and lower-income individuals.1

Twelve percent of American households were food insecure in 2017, meaning they were uncertain of having, or were unable to acquire, enough food to meet the needs of all their members because they had insufficient money or other resources for food.3 There are well-established associations between food insecurity and chronic diseases, including obesity, diabetes, hypertension, HIV/AIDS, and mood disorders.4-6 Importantly, the relationship between food insecurity and chronic illness is bidirectional or cyclic, with chronically ill individuals facing financial challenges leading to food insecurity and food-insecure individuals being forced to make a trade-off between food and medical care, leading to poor health outcomes and exacerbating financial hardship.7,8

Estimates of food insecurity among cancer survivors vary widely, reflecting differences in the characteristics of the populations studied.9,10 Gany et al9 found 56% of cancer patients at underserved oncology clinics in New York City were food insecure, and Simmons et al10 reported a food-insecurity prevalence of 17% in a primarily non-Hispanic white sample of patients from an academic cancer center in Kentucky. Using national data from the 2015 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, Charkhchi et al4 found 23% of individuals with a history of cancer report food insecurity.

Despite mounting evidence that financial hardship among cancer survivors is associated with suboptimal treatment adherence,2,11-13 poorer quality of life,14,15 and increased risk of death,16,17 the trade-off between food and medical care remains poorly understood. In the study by Simmons et al,10 55% of patients with cancer who were food insecure reported not taking a prescribed medication because of cost. Patients with cancer and food insecurity may be an extreme subset of those reporting financial problems, of whom 18% report delaying medical care.18 The objectives of this study were to identify sociodemographic characteristics associated with food insecurity and to investigate the relationship between new and persistent food insecurity and forgoing, delaying, or making changes to medical care because of cost.

METHODS

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of cancer survivors identified from the New Mexico Tumor Registry (NMTR). Individuals diagnosed between the ages of 21 and 64 years, with a first primary, invasive breast, colorectal, or prostate cancer between 2008 and 2016 were sampled from NMTR records. We selected these 3 cancer types because they are among the most common and they represent the 3 cancers with the fastest growing costs of care in the United States.19 The study was limited to adults aged < 65 years because prior studies indicate an inverse association between age and financial hardship.12,13,20 To increase the socioeconomic diversity of the study population, all Medicaid-insured and uninsured cancer survivors and a random sample of privately insured survivors, sampled in a 1:1 ratio to the Medicaid/uninsured group on the basis of year of diagnosis, were mailed an introductory study letter directly from NMTR. Those who did not opt-out of additional contact were approached by our study team and screened for eligibility. Eligible participants were those who spoke English or Spanish; had private insurance, Medicaid, or were uninsured; and their income was < $24,000 (approximately 200% of the federal poverty level for an individual21) at the time of their cancer diagnosis. Participant recruitment and data collection occurred between August 1, 2018, and February 1, 2019.

Eligible participants were invited to complete a paper, web-based, or telephone survey, depending on their preference. Food insecurity was measured using the 2-item Hunger VitalSign assessment (Children’s HealthWatch, Boston, MA). This brief food-insecurity screener was chosen over other measures because of its low participant burden and high sensitivity (97%) and specificity (83%) when compared with the 18-item Food Security Supplement.22 Participants were presented with the following statements: (1) Within the past 12 months, we worried whether our food would run out before we got money to buy more; and (2) within the past 12 months, the food we bought just didn’t last and we didn’t have money to get more.

For each food-insecurity question, participants chose among the responses “often true,” “sometimes true,” or “never true.” Those who responded often true or sometimes true were classified as food insecure, in accordance with previous literature.5,22-24 Participants were asked to respond to the two questions for two different time points: in the year before and the year after being diagnosed with cancer. Individuals were then classified as persistently food secure if they were food secure in the year before their cancer diagnosis and in the year after diagnosis. Those who were food secure in the year before but food insecure in the year after diagnosis were classified as newly food insecure, and those who were food insecure in both the year before and the year after diagnosis were classified as persistently food insecure. Newly food-secure patients and those with missing data were excluded from the final analytic data set.

Outcomes were ascertained in the survey using the question: Did you ever delay, forgo, or have to make other changes to any of the following types of care because of cost? Response options were: prescription medicine, visit to specialists, treatment other than prescription medicine, follow-up care, and mental health services. Participants were instructed to mark all that apply.

Covariates of interest obtained from the survey included self-reported comorbid conditions, education level, annual household income, household size, debt, and marital status. In addition, age at diagnosis, date of cancer diagnosis, cancer type, cancer stage, sex, race, ethnicity, zip code of residence, and indicator variables (yes/no) for receipt of surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and immunotherapy were obtained from NMTR for all potentially eligible participants. Rural-Urban Commuting Area codes were used to classify rural residence on the basis of zip code of residence.25 Marital status and sex were combined (married male, unmarried male, married female, unmarried female) on the basis of prior work showing different distributions of financial burden across these stratum among cancer survivors younger than 65 years.11,26 Time since diagnosis was calculated by subtracting the date of diagnosis from the date of survey completion.

All data from NMTR, paper, online, and telephone surveys were entered into a REDCap database (https://www.project-redcap.org/) using double-data entry for paper surveys to ensure accuracy.27 The Institutional Review Board of the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center reviewed and approved all study activities.

Descriptive statistics were used to compare survey respondents and nonrespondents and to characterize study participants’ clinical and demographic characteristics. Differences in the demographic and clinical characteristics between respondents and nonrespondents were compared using Student t tests for continuous variables and Pearson χ2 tests for categorical variables. We used polytomous logistic regression to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs for the associations between covariates of interest and food insecurity, comparing newly food-insecure and persistently food-insecure cancer survivors with persistently food-secure cancer survivors. Logistic regression was used to assess associations between new and persistent food insecurity, covariates of interest, and our outcomes of interest: delaying, forgoing, or making changes to prescription medicine, visits to specialists, treatment other than prescription medicine, follow-up care, or mental health services. Using existing literature and the results of our bivariate analyses, we developed a multivariable logistic regression model for each outcome of interest with a unique subset of covariates. We assessed the extent to which the associations between food insecurity and delaying, forgoing, or making changes to each type of medical care varied by cancer type by comparing nested models, with and without categorical interaction terms, using likelihood ratio tests. We applied backward elimination to select the final subset of covariates, including only those that remained significant at the α < 0.1 level. All logistic regression models used propensity score weighting to account for differences between respondents and nonrespondents. Propensity scores were calculated on the basis of variables available from NMTR on respondents and nonrespondents, including all variables listed in Table 1. Statistical significance was assessed at the P < .05 level. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Participants and Nonrespondents (N = 1,211)

RESULTS

Of a total of 1,211 eligible individuals who were identified from NMTR and invited to complete the survey, 394 completed the survey (response rate, 33%). Compared with nonrespondents, study participants were more likely to be female (70% v 59%; P < .001), non-Hispanic white (56% v 47%; P = .002), have stage I breast cancer (29% v 20%; P = .004), and more likely to have received cancer-directed surgery (88% v 82%; P = .026; Table 1).

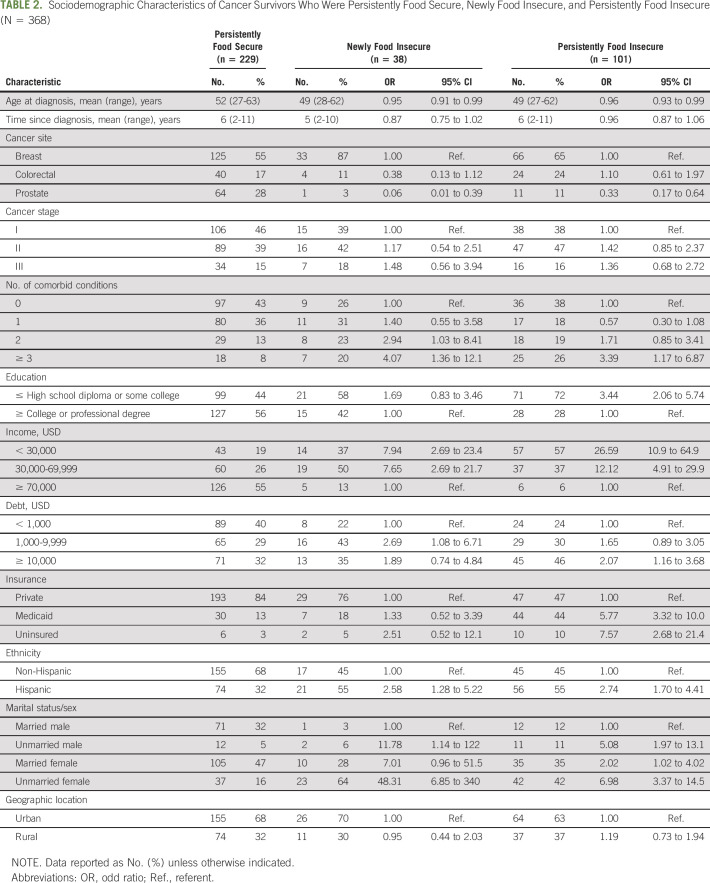

Among study participants (n = 394), 229 (58%) were food secure in both the year before and the year after cancer diagnosis, making up our persistently food-secure group (Table 2). Thirty-eight participants (10%) were newly food insecure and 101 (26%) were persistently food insecure. Thirteen individuals were food insecure before diagnosis and became food secure the year after diagnosis, and 13 participants were missing data needed to classify their food-insecurity status. The demographic characteristics of the latter 26 individuals who were newly food secure or had missing data did not differ substantially from the full study cohort and were excluded from additional analyses.

TABLE 2.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Cancer Survivors Who Were Persistently Food Secure, Newly Food Insecure, and Persistently Food Insecure (N = 368)

Compared with persistently food-secure cancer survivors, newly food-insecure survivors were diagnosed with cancer at younger ages (mean, 49 years v 52 years; OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.91 to 0.99; Table 2). Newly food-insecure cancer survivors were also more likely to have ≥ 3 comorbid conditions (OR, 4.07; 95% CI, 1.36 to 12.1), an income < $30,000 (OR, 7.94; 95% CI, 2.69 to 23.4), debt of $1,000-$9,999 (OR, 2.69; 95% CI, 1.08 to 6.71), and were more likely to be Hispanic (OR, 2.58; 95% CI, 1.28 to 5.22), unmarried men (OR, 11.8; 95% CI, 1.14 to 122.1) or unmarried women (OR, 48.3; 95% CI, 6.85 to 340.9). Similarly, when we compared persistently food-insecure with persistently food-secure cancer survivors, we found younger age, more comorbid conditions, lower income, higher debt, Hispanic ethnicity, and being unmarried or female were associated with persistent food insecurity. In addition, persistently food-insecure cancer survivors were more likely to have a high school education or less (OR, 3.44; 95% CI, 2.06 to 5.74) and to be insured by Medicaid (OR, 5.77; 95% CI, 3.32 to 10.0) or uninsured (OR, 7.57; 95% CI, 2.68 to 21.4). Compared with breast cancer survivors, prostate cancer survivors were substantially less likely to report new (OR, 0.06; 95% CI, 0.01 to 0.39) or persistent (OR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.17 to 0.64) food insecurity. No association between food insecurity and time since diagnosis or rurality was observed in our data.

Twenty-four percent of newly food-insecure cancer survivors and 21% of persistently food-insecure survivors reported forgoing, delaying, or making changes to prescription medication, compared with 8% of persistently food-secure cancer survivors (Appendix Fig A1, online only). Newly food-insecure cancer survivors consistently had the highest probability of forgoing, delaying, or making changes to all types of care, with the highest relative disparity observed for mental health services.

After controlling for participant sociodemographic characteristics, we found that compared with persistently food-secure cancer survivors, newly food-insecure survivors were nearly 3 times as likely to report forgoing, delaying, or making changes to prescription medications (OR, 2.82; 95% CI, 1.02 to 7.79); 9 times as likely to report forgoing, delaying, or making changes to treatment other than prescription medication (OR, 9.23; 95% CI, 2.90 to 29.3); 3 times as likely to report forgoing, delaying, or making changes to specialist visits (OR, 3.29; 95% CI, 1.22 to 8.88) and follow-up care (OR, 3.33; 95% CI, 1.39 to 8.01); and nearly 7 times as likely to report forgoing, delaying, or making changes to mental health services (OR, 6.68; 95% CI, 2.20 to 20.3; Table 3). We did not observe evidence of interactions between cancer type and food insecurity.

TABLE 3.

Multivariable Adjusted Association Between Food Insecurity and Forgoing, Delaying, or Making Changes to Medical Care Because of Cost

Compared with persistently food-secure cancer survivors, persistently food-insecure cancer survivors were also significantly more likely to forgo, delay, or make changes to prescription medication (OR, 3.04; 95% CI, 1.36 to 6.77), treatment other than prescription medication (OR, 9.93; 95% CI, 3.53 to 27.9), specialist visits (OR, 3.93; 95% CI, 1.76 to 8.78), follow-up care (OR, 3.23; 95% CI, 1.70 to 6.15), and mental health services (OR, 5.76; 95% CI, 2.35 to 14.1).

DISCUSSION

In this socioeconomically diverse sample of nearly 400 breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer survivors, 36% (10% newly food-insecure and 26% persistently food insecure) were food insecure in the year after cancer diagnosis. Newly and persistently food-insecure cancer survivors tended to be younger, Hispanic, unmarried, and have lower incomes and higher debt, compared with persistently food-secure cancer survivors. In addition, new and persistent food insecurity was strongly associated with forgoing, delaying, or making changes to all kinds of medical care. These findings are important because they suggest screening for and addressing food insecurity among individuals diagnosed with cancer may be a promising strategy for improving treatment adherence and reducing socioeconomic disparities in cancer outcomes.

Previous studies have not distinguished between new and persistent food insecurity, yet they found similar characteristics were associated with food insecurity overall.9,10 Gany et al9 found younger age, Spanish language, poor health care access, and having less money for food were associated with food insecurity among urban, low-income patients with cancer. In Kentucky, Simmons et al10 found that food-insecure cancer survivors tended to have lower education levels, lower income, Medicaid or Medicare, and were more likely to be unemployed than food-secure cancer survivors, and they were significantly more likely than food-secure survivors to not take, or take fewer, prescribed medications. In the general population and in other chronic disease settings, food insecurity is consistently associated with postponing medical care.4,28-30 Our finding that both incident (ie, newly food-insecure) and prevalent (ie, persistently food-insecure) cancer survivors are similarly likely to forgo, delay, or make changes to medical care is important because it suggests either preventing new food insecurity arising as a consequence of the financial burden of cancer care, or intervening with cancer survivors who are already insecure, may have the potential to affect clinical outcomes.

The similarity in the magnitude of the associations observed for newly and persistently food-insecure cancer survivors in our study supports the cyclic model of the relationship among food insecurity, poor health, treatment adherence, and financial hardship proposed by Seligman and Shillinger.7 As food-insecure individuals forgo, delay, or make changes to necessary medical care, their health may worsen. By initially prioritizing food over medical care, the downstream effect may be increased health care use, especially in high-cost emergency department use and hospitalizations.29,31 Increased use of high-cost services, rather than lower-cost preventive medical care, results in higher medical expenditures,8,32 thus worsening existing financial hardship and potentially prolonging or exacerbating food insecurity. Many of the characteristics we found associated with food insecurity also were associated with financial hardship among cancer survivors in prior studies.1,33,34 However, despite numerous calls to develop and test interventions to reduce financial hardship,35-37 no evidence-based strategies are currently available for implementation in the clinic, to our knowledge. Routinely screening for food insecurity using the validated 2-item assessment we used in our survey, intervening to prevent new food insecurity among those at greatest risk, and intervening to alleviate existing food insecurity present feasible alternatives to directly addressing financial well-being that may improve cancer care delivery for the most financially vulnerable cancer survivors. Such a focus on food insecurity, rather than financial hardship, may also be more palatable to the one-third of oncologists who find the idea of discussing costs with patients highly uncomfortable.38 Potential food-insecurity interventions might include navigating patients to existing resources including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, which is proven to reduce food insecurity,39 or to local programs providing access to free healthy food, either at the point of care or through partnerships with community food banks.

The results of this study should be interpreted in context of its limitations. Although we asked participants to recall their experience in the year before and the year after cancer diagnosis, all data on exposures and outcomes were collected at a single point in time, making the direction of causality ambiguous. In addition, participants may have overreported food insecurity if they recalled and erroneously reported instances of food insecurity that occurred outside of these 2 time points. The 2-item screener we used has not been validated for recall of past exposures occurring beyond the 12-month period of interest, and it precludes investigation of the severity of food insecurity.22 However, we did not find associations between time since diagnosis and the likelihood of reporting food insecurity, suggesting that recall bias, if present, is nondifferential in regard to time since exposure. Moreover, this 2-item assessment is recommended for routine use in clinical practice,24,40 strengthening the translational implications of our findings. Furthermore, we only had data on the first course of cancer-directed treatment, limiting our ability to characterize subsequent courses of cancer therapy, duration of cancer therapy, or cancer therapy completion. Despite using evidence-based survey methods, including participant incentives and sequential contact, the response rate for our survey was 33%. We used propensity score weighting to account for differences between nonrespondents and respondents, but this response rate may still limit the generalizability of our results. Also limiting generalizability was our oversampling of Medicaid and uninsured participants and our exclusion of individuals older than 65 years. Although sampling based on age and insurance type increased the sociodemographic diversity of our sample, thus providing more statistical power to examine the relationship between food insecurity and forgoing, delaying, or making changes to medical care, the estimates of the prevalence and cumulative incidence of food insecurity in our sample cannot be generalized to all cancer survivors.

In conclusion, food insecurity represents a pressing and actionable threat to access to medical care among cancer survivors. Studies are needed to investigate whether routinely screening for and addressing food insecurity among cancer survivors may be a cost-effective strategy to improve treatment adherence, improve quality of life, and, ultimately, prevent death.

Appendix

Fig A1.

Estimates of forgoing, delaying, or making changes to medical care.

PRIOR PRESENTATION

Presented in part at the International Society for Pharmacoeconomic and Outcomes Research 2019 Annual Meeting, New Orleans, LA, May 18-22, 2019.

SUPPORT

Supported by the American Cancer Society (Institutional Research Grant No. HSC-21094 (J.A.M.); the University of New Mexico Cancer Center (Support Grant No. P30CA118100; National Cancer Institute ( Task Order No. HHSN26100001 Contract No. HHSN2612018000141 [C.L.W.]; and Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health National Center for Research Resources (No. 8UL1TR000041).This research used the facilities or services of the Behavioral Measurement and Population Sciences Shared Resource, a facility supported by the State of New Mexico and the University of New Mexico Cancer Center (P30CA118100).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Jean A. McDougall, Angela L. W. Meisner, Charles L. Wiggins, Elizabeth Yakes Jimenez

Administrative support: Charles L. Wiggins

Provision of study material or patients: Angela L. W. Meisner, Charles L. Wiggins

Collection and assembly of data: Jean A. McDougall, Jessica Anderson, Shoshana Adler Jaffe, Angela L. W. Meisner, Charles L. Wiggins

Data analysis and interpretation: Jean A. McDougall, Jessica Anderson, Shoshana Adler Jaffe, Dolores D. Guest, Andrew L. Sussman, Angela L. W. Meisner, Elizabeth Yakes Jimenez, V. Shane Pankratz

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Food Insecurity and Forgone Medical Care Among Cancer Survivors

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Elizabeth Yakes Jimenez

Research Funding: Relypsa (Inst)

Other Relationship: Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (Inst)

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altice CK, Banegas MP, Tucker-Seeley RD, et al. Financial hardships experienced by cancer survivors: A systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;109:djw205. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: A pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18:381–390. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, et al: Household Food Security in the United States in 2017. Economic Research Report 256. 2018 https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=90022.

- 4.Charkhchi P, Fazeli Dehkordy S, Carlos RC. Housing and food insecurity, care access, and health status among the chronically ill: An analysis of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:644–650. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4255-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Decker D, Flynn M: Food insecurity and chronic disease: Addressing food access as a healthcare issue. R I Med J 101:28-30, 2018. [PubMed]

- 6.Laraia BA. Food insecurity and chronic disease. Adv Nutr. 2013;4:203–212. doi: 10.3945/an.112.003277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seligman HK, Schillinger D. Hunger and socioeconomic disparities in chronic disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:6–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1000072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berkowitz SA, Basu S, Meigs JB, et al. Food insecurity and health care expenditures in the United States, 2011-2013. Health Serv Res. 2018;53:1600–1620. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gany F, Lee T, Ramirez J, et al. Do our patients have enough to eat?: Food insecurity among urban low-income cancer patients. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2014;25:1153–1168. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2014.0145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simmons LA, Modesitt SC, Brody AC, et al. Food insecurity among cancer patients in Kentucky: A pilot study. J Oncol Pract. 2006;2:274–279. doi: 10.1200/jop.2006.2.6.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banegas MP, Dickerson JF, Kent EE, et al. Exploring barriers to the receipt of necessary medical care among cancer survivors under age 65 years. J Cancer Surviv. 2018;12:28–37. doi: 10.1007/s11764-017-0640-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDougall JA, Banegas MP, Wiggins CL, et al. Rural disparities in treatment-related financial hardship and adherence to surveillance colonoscopy in diverse colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27:1275–1282. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shankaran V, Jolly S, Blough D, et al. Risk factors for financial hardship in patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer: A population-based exploratory analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1608–1614. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.9511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lathan CS, Cronin A, Tucker-Seeley R, et al. Association of financial strain with symptom burden and quality of life for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1732–1740. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zafar SY, McNeil RB, Thomas CM, et al. Population-based assessment of cancer survivors’ financial burden and quality of life: A prospective cohort study. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:145–150. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:980–986. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.6620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tucker-Seeley RD, Li Y, Subramanian SV, et al. Financial hardship and mortality among older adults using the 1996-2004 Health and Retirement Study. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:850–857. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Yabroff KR, et al. Are survivors who report cancer-related financial problems more likely to forgo or delay medical care? Cancer. 2013;119:3710–3717. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, et al. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:117–128. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al. Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1143–1152. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation 2017 Poverty guidelineshttps://aspe.hhs.gov/2017-poverty-guidelines#threshholds

- 22.Gundersen C, Engelhard EE, Crumbaugh AS, et al. Brief assessment of food insecurity accurately identifies high-risk US adults. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20:1367–1371. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017000180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hager ER, Quigg AM, Black MM, et al. Development and validity of a 2-item screen to identify families at risk for food insecurity. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e26–e32. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Makelarski JA, Abramsohn E, Benjamin JH, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of two food insecurity screeners recommended for use in health care settings. Am J Public Health. 2017;107:1812–1817. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hart LG, Larson EH, Lishner DM. Rural definitions for health policy and research. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1149–1155. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.042432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Banegas MP, Guy GP, Jr, de Moor JS, et al. For working-age cancer survivors, medical debt and bankruptcy create financial hardships. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35:54–61. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Berkowitz SA, Seligman HK, Choudhry NK: Treat or eat: Food insecurity, cost-related medication underuse, and unmet needs. Am J Med 127:303-310.e3, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Kushel MB, Gupta R, Gee L, et al. Housing instability and food insecurity as barriers to health care among low-income Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:71–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00278.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sattler EL, Lee JS. Persistent food insecurity is associated with higher levels of cost-related medication nonadherence in low-income older adults. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;32:41–58. doi: 10.1080/21551197.2012.722888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhargava V, Lee JS. Food Insecurity and health care utilization among older adults in the United States. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;35:177–192. doi: 10.1080/21551197.2016.1200334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia SP, Haddix A, Barnett K. Incremental health care costs associated with food insecurity and chronic conditions among older adults. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15:180058. doi: 10.5888/pcd15.180058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP, Jr, et al. Financial hardship associated with cancer in the United States: Findings from a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:259–267. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.0468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yabroff KR, Zhao J, Han X, et al. Prevalence and correlates of medical financial hardship in the USA. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:1494–1502. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05002-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shankaran V, Ramsey S. Addressing the financial burden of cancer treatment: From copay to can’t pay. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:273–274. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.0423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tucker-Seeley RD, Yabroff KR. Minimizing the “financial toxicity” associated with cancer care: Advancing the research agenda. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;108:djv410. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zafar SY. Financial toxicity of cancer care: It’s time to intervene. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;108:djv370. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schrag D, Hanger M. Medical oncologists’ views on communicating with patients about chemotherapy costs: A pilot survey. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:233–237. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. White House Council of Economic Advisors: Long-Term Benefits of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. 2015. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/documents/SNAP_report_final_nonembargo.pdf.

- 40.Patel KG, Borno HT, Seligman HK. Food insecurity screening: A missing piece in cancer management. Cancer. 2019;125:3494–3501. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]