Key Points

Question

Did clinicians affiliated with health systems composed of hospitals and multispecialty group practices have better performance ratings than their peers under the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS)?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of 636 552 clinicians with MIPS data for 2019 (based on clinician performance in 2017), those with health system affiliations compared with clinicians without such affiliations had a mean MIPS performance score of 79 vs 60 on a scale of 0 to 100, with higher scores intended to represent better performance. This difference was statistically significant.

Meaning

Clinician affiliation with a health system was associated with significantly better 2019 MIPS performance ratings, but whether this reflects a difference in quality of care is unknown.

Abstract

Importance

Integration of physician practices into health systems composed of hospitals and multispecialty practices is increasing in the era of value-based payment. It is unknown how clinicians who affiliate with such health systems perform under the new mandatory Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) relative to their peers.

Objective

To assess the relationship between the health system affiliations of clinicians and their performance scores and value-based reimbursement under the 2019 MIPS.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Publicly reported data on 636 552 clinicians working at outpatient clinics across the US were used to assess the association of the affiliation status of clinicians within the 609 health systems with their 2019 final MIPS performance score and value-based reimbursement (both based on clinician performance in 2017), adjusting for clinician, patient, and practice area characteristics.

Exposures

Health system affiliation vs no affiliation.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was final MIPS performance score (range, 0-100; higher scores intended to represent better performance). The secondary outcome was MIPS payment adjustment, including negative (penalty) payment adjustment, positive payment adjustment, and bonus payment adjustment.

Results

The final sample included 636 552 clinicians (41% female, 83% physicians, 50% in primary care, 17% in rural areas), including 48.6% who were affiliated with a health system. Compared with unaffiliated clinicians, system-affiliated clinicians were significantly more likely to be female (46% vs 37%), primary care physicians (36% vs 30%), and classified as safety net clinicians (12% vs 10%) and significantly less likely to be specialists (44% vs 55%) (P < .001 for each). The mean final MIPS performance score for system-affiliated clinicians was 79.0 vs 60.3 for unaffiliated clinicians (absolute mean difference, 18.7 [95% CI, 18.5 to 18.8]). The percentage receiving a negative (penalty) payment adjustment was 2.8% for system-affiliated clinicians vs 13.7% for unaffiliated clinicians (absolute difference, −10.9% [95% CI, −11.0% to −10.7%]), 97.1% vs 82.6%, respectively, for those receiving a positive payment adjustment (absolute difference, 14.5% [95% CI, 14.3% to 14.6%]), and 73.9% vs 55.1% for those receiving a bonus payment adjustment (absolute difference, 18.9% [95% CI, 18.6% to 19.1%]).

Conclusions and Relevance

Clinician affiliation with a health system was associated with significantly better 2019 MIPS performance scores. Whether this represents differences in quality of care or other factors requires additional research.

This study uses data from the Medicare Physician Compare database to assess associations between clinician affiliation with health systems and performance scores and value-based reimbursement under the 2019 Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS).

Introduction

The first payment year of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) mandatory Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) was 2019. Under this program, which includes nearly all US clinicians, participants received bonuses or penalties of up to 4% of Medicare reimbursement based on their performance scores for quality of care and cost measures.1,2 By 2022, the MIPS will adjust clinicians’ payments up or down by up to 9%.1,2

As Medicare reimbursement shifts to value-based payment, integration of physician practices within health systems (ie, organizations composed of both hospitals and multispecialty group practices) is increasing.3,4,5,6,7,8 The proportion of practices affiliated with health systems increased from 7% in 2009 to 25% in 2015,7 and hospital ownership of primary care, oncology, and cardiology practices increased by 16, 30, and 34 percentage points, respectively, over a similar time frame.5,6

There is reason to think that health system affiliation might be associated with performance under the MIPS. Integration in the health care delivery system is associated with higher screening rates, better quality on process of care measures for chronic conditions such as diabetes, improved meaningful use of electronic health records, and more use of care management.9,10,11,12,13 In addition, practices affiliated with health systems may have more resources to support the measurement, selection, and reporting of quality measures to the CMS.14 The CMS previously reported15 clinicians participating in the MIPS in 2019 as part of large practices achieved performance scores that were 71% higher than those participating as part of small practices, but did not assess health system affiliation or control for other practice characteristics.

This study focused on 2 questions. First, did clinicians affiliated with health systems have better performance scores and value-based reimbursement under the 2019 MIPS than their unaffiliated peers? Second, were there differences in the rates of reporting or performance for key individual performance measures that may help explain these differences?

Methods

This study was deemed exempt by the Saint Louis University institutional review board and informed consent was waived. The MIPS, authorized under the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act, is a mandatory pay-for-performance program for clinicians participating in Medicare in the outpatient setting.16 Participating clinicians include primary care physicians, specialists, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants who bill Medicare Part B for professional services. The MIPS has the default track, which includes most clinicians participating as individuals or groups, and the alternative payment models track, which includes all clinicians participating in MIPS alternative payment models such as the Medicare Shared Savings Program.1,2 Clinicians participating in advanced alternative payment models, such as high–risk-bearing accountable care organizations, and clinicians not meeting the low-volume patient cutoff of 100 patients covered by Medicare Part B were excluded from the MIPS.

The MIPS began measuring clinician performance in 2017, and these were the data used to make the program’s first payment adjustments in 2019. Clinicians’ performance was scored from a set of 388 self-selected measures across the following domains: (1) quality of care, (2) meaningful use of electronic health records, (3) improvement activities for patient care processes, and (4) cost.17 Cost was weighted at 0% during the 2019 payment year, therefore, performance scores were based on 386 measures from the first 3 domains.

Study Population

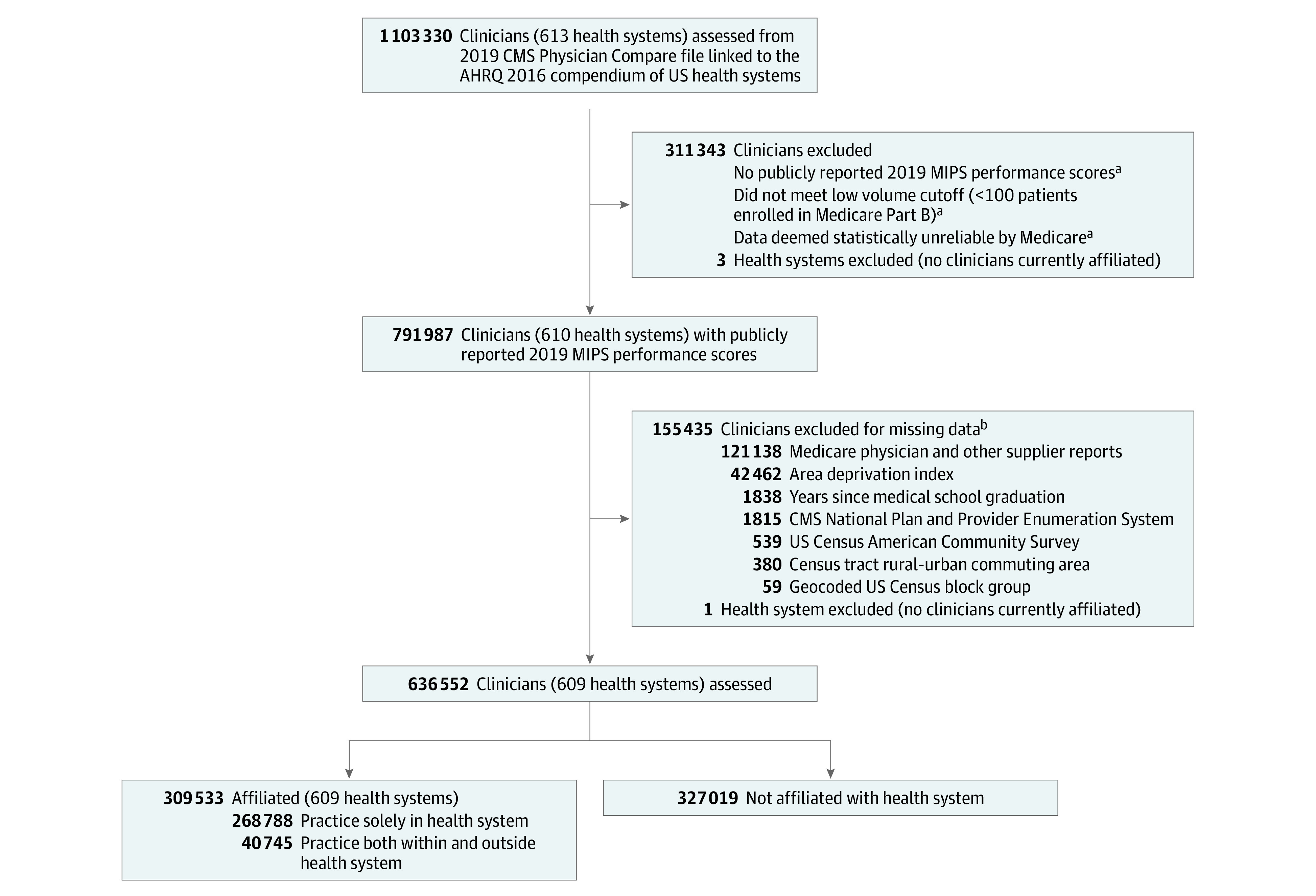

We included all clinicians who participated in the MIPS and had a publicly reported 2019 final performance score and records on Physician Compare in September 2019.18 Some low-volume clinicians who participated in the MIPS did not have scores for 2019 publicly reported due to their data not meeting acceptable thresholds for statistical reliability (Figure 1). We linked the above data using national provider identifiers (NPIs) and group practice identifiers with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2016 compendium of US health systems, as well as with the National Plan and Provider Enumeration System and the 2017 Medicare physician and other supplier reports.

Figure 1. Selection of Study Sample.

AHRQ indicates Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; MIPS, Merit-based Incentive Payment System.

aPrecise numbers were not available for these exclusion categories.

bClinicians could have been excluded for more than 1 reason. Excluded clinicians did not have records in the following databases: (1) 2019 National Plan and Provider Enumeration System; (2) 2017 Medicare physician and other supplier reports; (3) 2015 geocoded US Census block group data; (4) 2015 area deprivation index Census block group data; and (5) 2010 Census tract rural-urban commuting area codes.

We identified the US Census block groups and Census tracts of clinician practice locations by geocoding the street addresses of clinicians listed on Physician Compare and linked this with the 2015 American Community Survey, the 2015 area deprivation index,19 and the 2010 Census tract rural-urban commuting area codes. We excluded clinicians because of missing records or data in the above-linked data sets for the variables of interest; however, these clinicians were included in a sensitivity analysis to test the robustness of the findings.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

The primary outcome was clinician 2019 final MIPS performance score (range, 0-100; higher scores intended to represent better performance) as publicly reported on Physician Compare.18 Although the CMS scored and reimbursed clinicians based on their unique NPI tax identification number combinations, Physician Compare reported MIPS performance data only at the NPI level. Thus, a number of clinicians had multiple MIPS performance scores reported for their NPIs in Physician Compare. We applied the following hierarchy developed by the CMS20 to identify a unique final score and payment adjustment for individual NPIs: (1) clinicians participating in MIPS alternative payment models were assigned the highest score they received as part of any alternative payment model entity; (2) all other clinicians participating in MIPS were assigned the highest score they received.

The secondary outcome was 2019 MIPS payment adjustment for clinicians. The payment adjustments were derived using the payment thresholds published by the CMS,20 and binary indicators were used for each: (1) receipt of a negative (penalty) payment adjustment (for performance scores <3); (2) receipt of a positive payment adjustment (for performance scores >3); and (3) receipt of a bonus payment adjustment (for performance scores ≥70). Clinicians who received scores equal to 3 did not receive payment adjustments (positive or negative) per the CMS guidelines.

The secondary exploratory outcomes included the top 20 individual MIPS performance measures that were publicly reported on Physician Compare for clinicians in the study population. We ranked the measures by the number of clinicians reporting each measure and identified the top 20 measures along with the performance scores for each clinician reporting.

Health System Affiliation

We identified whether each clinician was affiliated with a health system using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2016 compendium of US health systems file, which contains all of the physician group practices affiliated within 626 major health systems in the US and was developed with health systems in 2016 based on Medicare billing patterns.21 Each health system includes at least 1 hospital and at least 1 multispecialty physician group practice including primary and specialty care clinicians, and are affiliated with each other through common ownership or joint management; some health systems are much larger and span multiple hospitals and practices. However, it is important to note that the lack of a health system affiliation does not imply belonging to a small practice.

Clinician, Patient, and Practice Area Characteristics

We used Physician Compare and the National Plan and Provider Enumeration System to identify clinician sex and the number of years since medical school graduation, as well as whether the clinicians were primary care physicians, advanced practitioners, or specialists. The clinicians affiliated with a safety net hospital (in the top quartile nationally of disproportionate share hospitals) and who had a practice location in a Census block group in the top quartile nationally for uninsured and Medicaid residents were identified as safety net providers.

We identified clinicians as being affiliated with a major teaching hospital if they were affiliated with a general acute care hospital with a resident-to-bed ratio of 0.25 or greater in the 2017 CMS impact file. We used the Medicare physician and other supplier reports to characterize the Medicare patient caseloads for clinicians based on the total number of Medicare beneficiaries they treated in 2017 and their mean risk scores for Hierarchical Condition Categories. In addition, we used clinicians’ geocoded data to identify the characteristics of their local practice area based on area deprivation index national rank,19 rural vs urban location, and Census region.

Statistical Analysis

We computed descriptive statistics on clinicians’ MIPS performance scores and payment adjustments, as well as individual patient caseload and local practice area characteristics, comparing clinicians affiliated vs not affiliated with health systems. We used the χ2 test to test for differences in proportions and the independent sample 2-tailed t test to test for differences in means and for significant differences between the clinicians by health system affiliation status. Next, we estimated clinician-level multivariable regression models that assessed the association between health system affiliation status and each of the clinicians’ 4 MIPS performance score outcomes (final score, negative payment adjustment, positive payment adjustment, and bonus payment adjustment).

We used linear regression for the primary outcome (final MIPS performance score) and logistic regression for the secondary outcome (payment adjustment indicators). In all the models, we adjusted for the individual clinician, patient caseload, and the local practice area characteristics listed above. We reported the results as marginal differences by modeling the mean response in the dependent variables to a 1-unit change in the independent variables. In addition, we reported the percentage differences by dividing the marginal differences by the population-dependent variable means.

In addition, we conducted a secondary exploratory analysis of the top 20 individual MIPS performance measures. We did this by computing descriptive statistics on the percentage of clinicians reporting on these measures and their mean performance scores, comparing clinicians affiliated with health systems vs their unaffiliated peers for the absolute differences in percentage reporting and the mean performance scores.

In the sensitivity analyses, we reassessed the associations from the primary analysis in an expanded population of clinicians excluded from the main models due to missing data, and in a reduced population having additional data available on patient caseload. We also reestimated the primary regression models by (1) adding market-level fixed effects for 306 hospital referral regions to estimate the within-market associations for system affiliation and (2) weighting by clinicians’ Medicare patient volume to assign higher weight to clinicians with greater volumes. In addition, to determine whether the associations with system affiliation differed by MIPS reporting status, we stratified the population by those who reported to MIPS as alternative payment models, groups, or individuals, and reestimated the primary regression models in these stratified groups.

The threshold for statistical significance was P < .05 using 2-sided tests. The analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) and Stata version 16 (StataCorp).

Results

Study Population

Of 1 103 330 individual clinicians listed in Physician Compare in 2019, 791 987 had publicly reported MIPS performance scores. There were missing data for 155 435 clinicians on key variables in the other linked data sets and they were excluded, leaving 636 552 clinicians within the 609 health systems in the final study population (Figure 1), 48.6% of whom were affiliated with a health system. Excluded clinicians had a significantly lower mean patient volume than included clinicians (103 vs 410, respectively, P < .001; eTable 1 in the Supplement). The eResults section in the Supplement provides additional details on the excluded clinicians.

Health system–affiliated clinicians were significantly more likely to be female than unaffiliated clinicians (46% vs 37%, respectively), primary care physicians (36% vs 30%), safety net providers (12% vs 10%), and affiliated with a major teaching hospital (38% vs 14%); had significantly less time elapsed since medical school graduation (20 years vs 23 years); had significantly lower Medicare patient volumes (361 vs 457 patients); and had significantly higher mean patient risk scores (1.81 vs 1.61) (P < .001 for each; Table 1). Clinicians affiliated with a health system were significantly more likely to be evaluated in the MIPS alternative payment models track than unaffiliated clinicians (13% vs 9%, respectively, P < .001; eTable 2 in the Supplement) and served significantly more dually enrolled Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries (28% vs 26%, P < .001; eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Table 1. Characteristics for 2019 Merit-based Incentive Payment System Participation.

| Characteristics | All clinicians | Clinician health system affiliationa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affiliatedb | Not affiliated | ||

| Individual clinicians | |||

| No. of cliniciansc | 636 552 | 309 533 | 327 019 |

| Sex, No. (%) | |||

| Female | 262 247 (41) | 142 146 (46) | 120 101 (37) |

| Male | 374 305 (59) | 167 387 (54) | 206 918 (63) |

| Time since medical school graduation, mean (SD), y | 21 (12) | 20 (12) | 23 (13) |

| Clinician specialty, No. (%) | |||

| Primary cared | 208 206 (33) | 111 738 (36) | 96 468 (30) |

| Advanced primary caree | 110 530 (17) | 60 463 (20) | 50 067 (15) |

| Otherf | 318 622 (50) | 137 707 (44) | 180 915 (55) |

| Affiliated with a safety net hospital, No. (%)g | 67 511 (11) | 35 816 (12) | 31 695 (10) |

| Affiliated with a major teaching hospital, No. (%)h | 161 741 (25) | 117 303 (38) | 44 438 (14) |

| Medicare patient caseload | |||

| Medicare beneficiaries in 2017, mean (SD)i | 410 (525) | 361 (512) | 457 (532) |

| Hierarchical Condition Categories risk score, mean (SD)j | 1.71 (0.79) | 1.81 (0.80) | 1.61 (0.78) |

| Local practice area | |||

| Area deprivation index national rank, mean (SD)k | 46 (27) | 46 (27) | 47 (27) |

| Population density, No. (%)l | |||

| Rural | 109 592 (17) | 51 042 (16) | 58 550 (18) |

| Urban | 576 914 (91) | 288 197 (93) | 288 717 (88) |

| US Census region, No. (%)l | |||

| Northeast | 138 443 (22) | 74 816 (24) | 63 627 (19) |

| Midwest | 161 046 (25) | 99 291 (32) | 61 755 (19) |

| South | 225 359 (35) | 84 263 (27) | 141 096 (43) |

| West | 120 331 (19) | 57 130 (18) | 63 201 (19) |

All differences between affiliated and not affiliated clinicians were statistically significant at P < .001.

Defined as affiliation within the 626 US health systems identified in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s 2016 Compendium of US Health Systems. Individual clinician affiliation identified by linking individual group practice identifiers assigned by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) listed in Physician Compare to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Group Practice file.

Received a publicly reported 2019 Merit-based Incentive Payment System score on Physician Compare. Clinicians were excluded if they had missing data for any of the study variables.

Includes geriatric medicine, internal medicine, family medicine, general practice, obstetrics/gynecology, and pediatric medicine.

Includes nurse practitioners and physician assistants.

Includes all other clinicians.

Determined using Physician Compare linked to disproportionate share hospital in the top quartile in the 2017 CMS impact file and at least 1 practice location was in a US Census block group top quartile nationally for uninsured and Medicaid residents as a percentage of total residents.

Identified using Physician Compare and defined as a general acute care hospital with a resident-to-bed ratio of 0.25 or greater in the 2017 CMS impact file.

Reported in the Medicare physician and other supplier reports. Due to extreme outliers in this data set, these data were winsorized using the entire distribution in the data set, setting the bottom 1% equal to the first percentile value (12) and the top 1% equal to the 99th percentile value (3034).

Based on age, sex, original reason for Medicare eligibility, dual Medicare and Medicaid enrollment, reside at long-term care facility, and 83 clinical conditions identified by diagnoses in Medicare claims. Higher scores imply sicker and higher-cost patients; score range, 0.39 to 12.45 (interquartile range, 1.15-2.05) and a median of 1.50. A mean score of 1.71 implies a patient caseload sicker than the national average.

A measure of local neighborhood area socioeconomic disadvantage derived from Census tract data on income, education, employment, and housing quality; score range, 0 to 100 (indicates the percentile rank of disadvantage for a given Census tract). The numbers closer to 100 indicate greater disadvantage and the numbers closer to 50 are indicative of the national average.

The percentages do not sum to 100% because some clinicians had multiple practice locations.

Individual Clinician Health System Affiliation Status and MIPS Performance

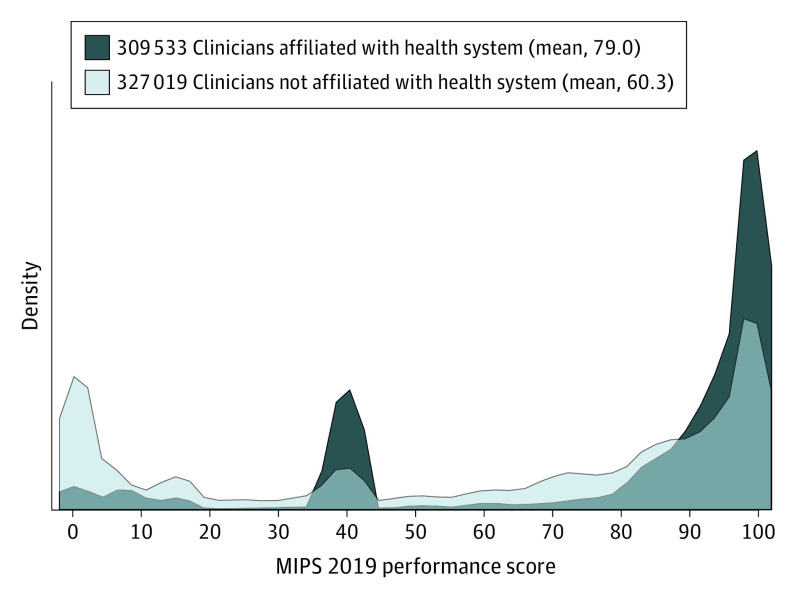

The mean final MIPS performance score was 69 (range, 0-100) and 8% of clinicians received negative (penalty) payment adjustments, 90% received positive payment adjustments, and 64% received bonus payment adjustments. An assessment of the distribution of clinicians by the primary outcome, MIPS final performance score, reveals a greater percentage of unaffiliated clinicians were in the left tail with lower scores and a greater percentage of affiliated clinicians were in the right tail with higher scores (Figure 2). As a result, the mean MIPS final performance score was 79.0 for affiliated clinicians vs 60.3 for unaffiliated clinicians (absolute mean difference, 18.7 [95% CI, 18.5 to 18.8]; Table 2).

Figure 2. Distribution of Clinicians Affiliated vs Not Affiliated With Health Systems by Their 2019 Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) Final Performance Score.

Density approximates the number of clinicians at each MIPS data point. The calculation is smoothed because MIPS score is continuous. Epanechnikov kernel with a bandwidth of 2 was used to minimize the mean integrated squared error of the kernel density estimate. A larger bandwidth would result in a smoother plot and a narrower bandwidth would result in a more jagged plot.

Table 2. Association of Clinician Health System Affiliation With 2019 Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) Performance Scores.

| Clinician health system affiliation | Absolute difference (95% CI) | Adjusted multivariable regression data for effect of health system affiliation (95% CI)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affiliated | Not affiliated | Marginalb | Percentagec | ||

| No. of cliniciansd | 309 533 | 327 019 | |||

| Primary outcome | |||||

| Final MIPS performance score, mean (SD)e | 79.0 (29.7) | 60.3 (38.5) | 18.7 (18.5 to 18.8) | 17.8 (17.6 to 17.9) | 25.6 (25.3 to 25.8) |

| Secondary outcome | |||||

| MIPS payment adjustment, %f | |||||

| Negative (penalty)g | 2.8 | 13.7 | −10.9 (−11.0 to −10.7) | −8.3 (−8.4 to −8.2) | −99.1 (−100.5 to −97.8) |

| Positiveh | 97.1 | 82.6 | 14.5 (14.3 to 14.6) | 11.3 (11.2 to 11.5) | 12.6 (12.5 to 12.8) |

| Bonusi | 73.9 | 55.1 | 18.9 (18.6 to 19.1) | 18.8 (18.5 to 19.0) | 29.2 (28.8 to 29.6) |

The total sample size was 636 552 clinicians. Adjusted for the individual clinician, Medicare patient caseload, and the local practice area characteristics listed in Table 1. Ordinary least-squares regression was used to model the final performance score outcome. Logistic regression was used to model the 3 binary payment adjustment indicators.

The change in the mean count of the dependent variable was associated with a 1-unit change in the independent variables.

Calculated as the marginal effect divided by the overall study population mean.

Received a publicly reported 2019 MIPS score on Physician Compare. Clinicians were excluded if they had missing data for any of the study variables.

Assessed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services as a weighted composite measure derived from among nearly 400 process and outcome measures and self-reported activities assessed during 2017 across the 3 domains of quality, advancing health care information (formerly termed meaningful use), and practice improvement activities.

The percentages do not sum to 100% because a small number of clinicians received MIPS performance scores equal to 3 and did not receive a payment adjustment.

Had final performance score of less than 3.

Had final performance score of greater than 3.

Had final performance score of 70 or greater.

For the secondary outcome, the percentage of affiliated clinicians who received a negative (penalty) payment adjustment was 2.8% vs 13.7% for unaffiliated clinicians (absolute difference, −10.9% [95% CI, −11.0% to −10.7%]), 97.1% vs 82.6%, respectively, for those who received a positive payment adjustment (absolute difference, 14.5% [95% CI, 14.3% to 14.6%]), and 73.9% vs 55.1% for those who received a bonus payment adjustment (absolute difference, 18.9% [95% CI, 18.6% to 19.1%]).

In the multivariable regression analyses, health system affiliation was associated with adjusted MIPS final performance scores that were 17.8 (95% CI, 17.6-17.9) points higher, a lower probability of receiving a negative (penalty) payment adjustment by 8.3 (95% CI, 8.2-8.4) percentage points, and higher probabilities of receiving a positive payment adjustment by 11.3 (95% CI, 11.2-11.5) percentage points and a bonus payment adjustment by 18.8 (95% CI, 18.5-19.0) percentage points (Table 2).

In the sensitivity analyses among an expanded population of 99.7% of MIPS-reporting clinicians (n = 789 939) with fewer linked control variables and among a narrower population of clinicians (n = 439 412) that added control variables for patient age, sex, dually enrolled status in Medicare and Medicaid, and race, the results were similar to the main analyses (eTable 4 in the Supplement). The analyses adding market fixed effects and weighted for patient volume (eTable 5 in the Supplement) were also similar. However, the associations were weaker in the analyses stratified by MIPS reporting status for those reporting in the alternative payment models track because none of them received MIPS scores in the penalty range, and for those reporting as individuals because the MIPS program required submission of less performance data from small practices in 2019 (eTable 6 in the Supplement).

Secondary Exploratory Analysis of Top 20 Individual MIPS Performance Measures

Clinicians affiliated with health systems vs unaffiliated clinicians had higher rates of reporting and mean performance scores on technology-dependent performance measures. For example, system-affiliated clinicians were more likely to report providing patients access to their personal health data compared with unaffiliated clinicians (52.8% vs 25.2%, respectively; absolute difference, 27.5% [95% CI, 27.3%-27.8%]) and had higher mean performance scores (88.5 vs 74.1; absolute difference, 14.4 [95% CI, 14.2-14.6]).

Similar patterns existed with 52.6% of affiliated clinicians reporting electronic prescribing vs 24.6% of unaffiliated clinicians (absolute difference, 28.0% [95% CI, 27.8%-28.3%]; mean performance score, 89.4 vs 84.9, respectively, absolute difference, 4.6 [95% CI, 4.4-4.7]); 51.6% vs 23.6% reporting that they can view, download, and transmit electronic reports (absolute difference, 28.0% [95% CI, 27.8%-28.2%]; mean performance score, 28.7 vs 16.7 [absolute difference, 12.0; 95% CI, 11.8-12.1]); and 51.4% vs 22.9% reporting that they have secure messaging (absolute difference, 28.5% [95% CI, 28.2%-28.7%]; mean performance score, 24.2 vs 19.6 [absolute difference, 4.6; 95% CI, 4.4-4.8]; Table 3).

Table 3. Exploratory Analysis of the Top 20 Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) Performance Measures Publicly Reported for 2019.

| Performance measure | % Reporting by clinician health system affiliationa | Absolute difference (95% CI) |

Mean performance scores by clinician health system affiliationb | Absolute difference (95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affiliated | Not affiliated | Affiliated | Not affiliated | |||

| No. of cliniciansc | 309 533 | 327 019 | ||||

| Provides patient access to personal health data | 52.8 | 25.2 | 27.5 (27.3 to 27.8) | 88.5 | 74.1 | 14.4 (14.2 to 14.6) |

| Electronic prescribing available | 52.6 | 24.6 | 28.0 (27.8 to 28.3) | 89.4 | 84.9 | 4.6 (4.4 to 4.7) |

| Provides patient-specific education | 52.2 | 24.0 | 28.2 (28.0 to 28.5) | 71.9 | 54.2 | 17.7 (17.4 to 17.9) |

| Can view, download, or transmit electronic reports | 51.6 | 23.6 | 28.0 (27.8 to 28.2) | 28.7 | 16.7 | 12.0 (11.8 to 12.1) |

| Offers secure messaging | 51.4 | 22.9 | 28.5 (28.2 to 28.7) | 24.2 | 19.6 | 4.6 (4.4 to 4.8) |

| Medication reconciliation available | 51.5 | 22.6 | 28.9 (28.7 to 29.1) | 86.9 | 87.8 | −0.9 (−1.1 to −0.8) |

| Facilitates health information exchange | 50.6 | 18.2 | 32.4 (32.2 to 32.6) | 23.1 | 27.6 | −4.6 (−4.8 to −4.3) |

| Medication reconciliation after hospital discharge available | 42.2 | 6.6 | 35.7 (35.5 to 35.9) | 78.9 | 71.7 | 7.3 (6.9 to 7.7) |

| Offers preventive care and screening | ||||||

| Tobacco use and cessation intervention | 15.5 | 5.7 | 9.8 (9.6 to 9.9) | 94.7 | 96.7 | −1.9 (−2.1 to −1.8) |

| Influenza immunization | 14.9 | 3.4 | 11.5 (11.4 to 11.6) | 74.5 | 71.7 | 2.8 (2.4 to 3.2) |

| Pneumococcal vaccination status for older adults | 14.9 | 3.4 | 11.5 (11.4 to 11.7) | 80.0 | 74.9 | 5.1 (4.7 to 5.4) |

| Colorectal cancer | 15.0 | 2.9 | 12.1 (12.0 to 12.2) | 67.5 | 67.1 | 0.3 (−0.1 to 0.8) |

| Clinical depression and follow-up plan | 14.5 | 2.5 | 12.0 (11.9 to 12.1) | 54.2 | 66.9 | −12.7 (−13.3 to −12.1) |

| Fall risk | 14.4 | 2.2 | 12.2 (12.1 to 12.3) | 80.5 | 81.5 | −1.0 (−1.4 to −0.5) |

| Type of documentation in the medical record | ||||||

| Current medications | 5.4 | 10.6 | −5.2 (−5.4 to −5.1) | 92.0 | 91.0 | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.4) |

| Care plan | 3.3 | 7.0 | −3.6 (−3.8 to −3.5) | 66.7 | 66.6 | 0.1 (−0.7 to 0.9) |

| Postanesthetic transfer of care measure (eg, procedure room to a postanesthesia care unit) | 3.6 | 5.1 | −1.5 (−1.6 to −1.4) | 96.4 | 96.0 | 0.4 (0.1 to 0.7) |

| Offers prevention measures | ||||||

| Central venous catheter–related bloodstream infections | 3.3 | 4.7 | −1.3 (−1.4 to −1.2) | 95.3 | 95.6 | −0.3 (−0.6 to 0) |

| Postoperative nausea and vomiting | 3.1 | 4.2 | −1.0 (−1.1 to −0.9) | 91.6 | 93.3 | −1.7 (−2.1 to −1.3) |

| Tracks radiology exposure (dose or time reported for procedures using fluoroscopy) | 2.8 | 3.8 | −1.1 (−1.1 to −1.0) | 86.3 | 86.9 | −0.5 (−1.1 to 0.1) |

Unless otherwise indicated.

To get the number of clinicians reporting for mean performance scores, multiply the percentage reporting by the total number of clinicians in the study population for each measure.

Had data publicly reported for individual MIPS measures on Physician Compare. Not all clinicians had data publicly reported on Physician Compare; however, they did have an overall MIPS score and MIPS payment adjustment reported.

The patterns were similar for the rates of reporting and mean performance on the following quality measures that may be dependent on technology: 52.2% of affiliated clinicians vs 24.0% of unaffiliated clinician reported providing patient-specific education (absolute difference, 28.2% [95% CI, 28.0%-28.5%]; mean performance score, 71.9 vs 54.2, respectively [absolute difference, 17.7; 95% CI, 17.4-17.9]) and 42.2% vs 6.6% reporting medication reconciliation after hospital discharge (absolute difference, 35.7% [95% CI, 35.5%-35.9%]; mean performance score, 78.9 vs 71.7 [absolute difference, 7.3; 95% CI, 6.9-7.7]). The differences in the reporting rates and mean performance score were mixed for other measures.

Discussion

For clinicians participating in the 2019 MIPS, health system affiliation was associated with substantially better performance scores. Health system affiliation was also associated with more favorable value-based reimbursement. These performance differences appear to be partly explained by the higher rates of reporting and better performance scores by system-affiliated clinicians on performance measures that were directly or indirectly dependent on technology.

Although these findings help clarify the financial consequences for clinicians based on the relationship between health system affiliation and success on the MIPS, the causal mechanisms underlying this relationship are less clear. Specifically, whether higher MIPS performance scores reflect better quality of care delivered to patients within health systems is uncertain. Some prior research suggests that integrated delivery systems may provide higher-quality care than practices unaffiliated with systems, which would suggest that MIPS bonus adjustment payments given to health system affiliates could reflect better care delivery at these practices.9,10,11,12,13 In addition, because the CMS allows clinicians to self-select the measures they report, better performance could reflect more strategic choices. Patient case mix also may differ in ways that influence performance; the CMS does not adjust for certain patient factors, such as poverty and dementia, which are known to be associated with poor performance outcomes.22,23,24

Although the analyses are exploratory, the pattern of results for the top 20 publicly reported individual MIPS performance measures may shed light on potential underlying mechanisms for the observed association between system affiliation and MIPS performance scores. Clinicians who were affiliated with health systems had higher rates of reporting and performance on technology-dependent measures, such as providing patients access to their health records or electronic prescribing compared with their unaffiliated peers. The support that a health system provides to its constituent practices may improve clinicians’ compliance with MIPS reporting requirements as well as their use of technology to deliver patient care. It is also worth noting that of the remaining 3 MIPS performance measurement domains (beyond the quality domain), 2 are directly dependent on technology: meaningful use of electronic health records and practice process improvement activities. Thus, health system affiliation may provide needed technology and management infrastructure that helps clinicians succeed across a range of metrics under value-based payment.

From the clinician perspective, these findings suggest that affiliating with health systems may be financially advantageous not only for market leverage, but also for value-based reimbursement purposes. Because the MIPS is a zero-sum payment system, the financial consequences of this phenomenon appear to be that system-affiliated clinicians are recipients of greater Medicare resources through value-based reimbursement at the expense of unaffiliated clinicians. This may amplify the trend toward clinician consolidation within health systems as clinicians seek sophisticated analytics and administrative help to successfully navigate the MIPS and maximize reimbursement.

Whether the MIPS will meaningfully improve quality or reduce costs over time is unknown. Research on prior Medicare value-based payment programs in the outpatient setting, notably the Shared Savings Program and the Value-Based Payment Modifier Program, have produced mixed results,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33 finding modest to no cost savings or improvements in the quality of care. Longer-term studies are needed to examine this program as future years of data become available.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the CMS did not publicly report MIPS performance data on low-volume Medicare participating clinicians, and very low–volume Medicare clinicians were excluded from the MIPS entirely. Study findings may not generalize to these groups.

Second, this is an observational study. Although the analysis controlled for a number of individual clinician, patient caseload, and local practice area factors, it is likely there is residual unmeasured confounding. For example, health systems could recruit all of the best-performing clinicians in local markets, rather than having a direct effect on publicly reported clinician performance scores. More research is needed to uncover the causal mechanisms behind these findings.

Conclusions

Clinician affiliation with a health system was associated with significantly better 2019 MIPS performance scores. Whether this represents differences in quality of care or other factors requires additional research.

eResults. Information on Clinicians Excluded From Study

eTable 1. Descriptive Statistics on Medicare-Serving Outpatient Clinicians Excluded From Study Compared to Clinicians Included in Study Population

eTable 2. Describing the 2019 Merit-Based Incentive Payment System Reporting Classification of Clinicians in the Study Population

eTable 3. Describing Outpatient Clinicians Participating in the 2019 Merit-Based Incentive Payment System and Comparing Those With and Without Health System Affiliations on Other Characteristics in the Medicare Physician and Other Supplier Reports

eTable 4. Sensitivity Analyses for Association of Clinician Health System Affiliation with 2019 Merit-Based Incentive Payment System Performance Scores in Expanded and Reduced Populations

eTable 5. Sensitivity Analyses for Association of Clinician Health System Affiliation with 2019 Merit-Based Incentive Payment System Performance Scores With Market-Level Fixed Effects and Weighted by Clinician Patient Volume

eTable 6. Sensitivity Analyses for Association of Clinician Health System Affiliation with 2019 Merit-Based Incentive Payment System Performance Scores Stratified by Clinician Reporting Category

References

- 1.Department of Health and Human Services Proposed rule: CY 2020 revisions to payment policies under the physician fee schedule and other changes to Part B payment policies. Fed Regist. 2019;84(157):40482-41289. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2020 quality payment program proposed rule overview factsheet with request for information for 2021. Accessed October 10, 2019. https://www.acr.org/-/media/ACR/Files/Advocacy/MPFS/07-29-2019-QPP-Fact-Sheet-CY2020-Proposed-Rule.pdf

- 3.Scott KW, Orav EJ, Cutler DM, Jha AK. Changes in hospital-physician affiliations in US hospitals and their effect on quality of care. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(1):1-8. doi: 10.7326/M16-0125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheffler RM, Arnold DR, Whaley CM. Consolidation trends in California’s health care system: impacts on ACA premiums and outpatient visit prices. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(9):1409-1416. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alpert A, Hsi H, Jacobson M. Evaluating the role of payment policy in driving vertical integration in the oncology market. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(4):680-688. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nikpay SS, Richards MR, Penson D. Hospital-physician consolidation accelerated in the past decade in cardiology, oncology. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(7):1123-1127. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richards MR, Nikpay SS, Graves JA. The growing integration of physician practices: with a Medicaid side effect. Med Care. 2016;54(7):714-718. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muhlestein DB, Smith NJ. Physician consolidation: rapid movement from small to large group practices, 2013-15. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(9):1638-1642. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlin CS, Dowd B, Feldman R. Changes in quality of health care delivery after vertical integration. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(4):1043-1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Machta RM, Maurer KA, Jones DJ, Furukawa MF, Rich EC. A systematic review of vertical integration and quality of care, efficiency, and patient-centered outcomes. Health Care Manage Rev. 2019;44(2):159-173. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Everson J, Richards MR, Buntin MB. Horizontal and vertical integration’s role in meaningful use attestation over time. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(5):1075-1083. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bishop TF, Shortell SM, Ramsay PP, Copeland KR, Casalino LP. Trends in hospital ownership of physician practices and the effect on processes to improve quality. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(3):172-176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Hanlon CE, Whaley CM, Freund D. Medical practice consolidation and physician shared patient network size, strength, and stability. Med Care. 2019;57(9):680-687. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Post B, Buchmueller T, Ryan AM. Vertical integration of hospitals and physicians: economic theory and empirical evidence on spending and quality. Med Care Res Rev. 2018;75(4):399-433. doi: 10.1177/1077558717727834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2017 Quality Payment Program Reporting Experience. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2019:1-30. [Google Scholar]

- 16.114th Congress. The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015. Accessed June 18, 2020. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/2/text

- 17.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Quality Payment Program Overview. Accessed January 11, 2020. https://qpp.cms.gov/about/qpp-overview

- 18.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Physician Compare datasets. Accessed January 18, 2020. https://data.medicare.gov/data/physician-compare

- 19.University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health 2015. area deprivation index version 2.0. Accessed January 11, 2020. https://www.neighborhoodatlas.medicine.wisc.edu/

- 20.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Fact sheet: 2019 Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) payment adjustments based on 2017 MIPS scores. Accessed January 11, 2020. https://qpp-cm-prod-content.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/70/2019%20MIPS%20Payment%20Adjustment%20Fact%20Sheet_2018%2011%2029.pdf

- 21.Jones D, Machta R, Rich E, Peckham K Comparative Health System Performance Initiative: compendium of US health systems, 2016, group practice linkage file, technical documentation. AHRQ Publication No. 19-0083. Accessed August 3, 2020. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/chsp/compendium/chsp-tin-linkage-file-tech-doc.pdf

- 22.Rathi VK, McWilliams JM. First-year report cards from the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS): what will be learned and what next? JAMA. 2019;321(12):1157-1158. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnston KJ, Bynum JPW, Joynt Maddox KE. The need to incorporate additional patient information into risk adjustment for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2020;323(10):925-926. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.22370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnston KJ, Wen H, Hockenberry JM, Joynt Maddox KE. Association between patient cognitive and functional status and Medicare total annual cost of care: implications for value-based payment. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(11):1489-1497. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts ET, Zaslavsky AM, McWilliams JM. The value-based payment modifier: program outcomes and implications for disparities. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(4):255-265. doi: 10.7326/M17-1740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Markovitz AA, Hollingsworth JM, Ayanian JZ, Norton EC, Yan PL, Ryan AM. Performance in the Medicare Shared Savings Program after accounting for nonrandom exit: an instrumental variable analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(1):27-36. doi: 10.7326/M18-2539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McWilliams JM, Hatfield L, Landon B, Chernew M. Spending Reductions in the Medicare Shared Savings Program: Selection or Savings? National Bureau of Economic Research; 2019. doi: 10.3386/w26403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McWilliams JM, Gilstrap LG, Stevenson DG, Chernew ME, Huskamp HA, Grabowski DC. Changes in postacute care in the Medicare Shared Savings Program. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(4):518-526. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McWilliams JM, Hatfield LA, Landon BE, Hamed P, Chernew ME. Medicare spending after 3 years of the Medicare Shared Savings Program. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(12):1139-1149. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1803388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McWilliams JM, Chernew ME, Landon BE. Medicare ACO program savings not tied to preventable hospitalizations or concentrated among high-risk patients. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(12):2085-2093. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kury FSP, Baik SH, McDonald CJ. Analysis of healthcare cost and utilization in the first two years of the Medicare Shared Savings Program using big data from the CMS enclave. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2017;2016:724-733. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cutler E, Karaca Z, Henke R, Head M, Wong HS. The effects of Medicare accountable organizations on inpatient mortality rates. Inquiry. 2018;55:46958018800092. doi: 10.1177/0046958018800092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Resnick MJ, Graves AJ, Thapa S, et al. . Medicare accountable care organization enrollment and appropriateness of cancer screening. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(5):648-654. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.8087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eResults. Information on Clinicians Excluded From Study

eTable 1. Descriptive Statistics on Medicare-Serving Outpatient Clinicians Excluded From Study Compared to Clinicians Included in Study Population

eTable 2. Describing the 2019 Merit-Based Incentive Payment System Reporting Classification of Clinicians in the Study Population

eTable 3. Describing Outpatient Clinicians Participating in the 2019 Merit-Based Incentive Payment System and Comparing Those With and Without Health System Affiliations on Other Characteristics in the Medicare Physician and Other Supplier Reports

eTable 4. Sensitivity Analyses for Association of Clinician Health System Affiliation with 2019 Merit-Based Incentive Payment System Performance Scores in Expanded and Reduced Populations

eTable 5. Sensitivity Analyses for Association of Clinician Health System Affiliation with 2019 Merit-Based Incentive Payment System Performance Scores With Market-Level Fixed Effects and Weighted by Clinician Patient Volume

eTable 6. Sensitivity Analyses for Association of Clinician Health System Affiliation with 2019 Merit-Based Incentive Payment System Performance Scores Stratified by Clinician Reporting Category