Abstract

This retrospective study uses data from the National Cancer Database of new cancer diagnoses across the US to examine trends in proportional diagnosis rates and management of patients with high-risk prostate cancer.

Introduction

Evidence suggests increasing rates of high-risk prostate cancer. Treatment for high-risk prostate cancer includes prostatectomy or radiotherapy. We examine trends in proportional diagnosis rates and management of patients with high-risk prostate cancer.

Methods

The National Cancer Database (NCDB) tabulates data from more than 70% of new cancer diagnoses across the US. The NCDB was queried to identify men with high-risk prostate cancer from 2004 to 2016. Men were classified as having high-risk disease if they had clinical stage T3-T4, a prostate-specific antigen level greater than 20 ng/mL, or a Gleason score of 8-10. The eFigure in the Supplement outlines the cohort selection.

Descriptive statistics for factors were reported as frequency. The Cochran-Armitage test identified trends in treatment with time. Multivariable logistic regression examined factors associated with each treatment. All tests were 2-sided and considered significant at an α level of .05. Analyses were performed with SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). This study follows STROBE reporting guidelines.

Results

Overall, 214 972 men were identified as having high-risk prostate cancer from 2004 to 2016 and 75 847 underwent prostatectomy and 104 635 underwent radiotherapy. White and black men comprised 79.2% and 16.1% of the cohort, respectively. Government-based insurance was used by 59.3% of the men. Approximately 82% of the cohort had a Charlson-Deyo comorbidity index of 0.

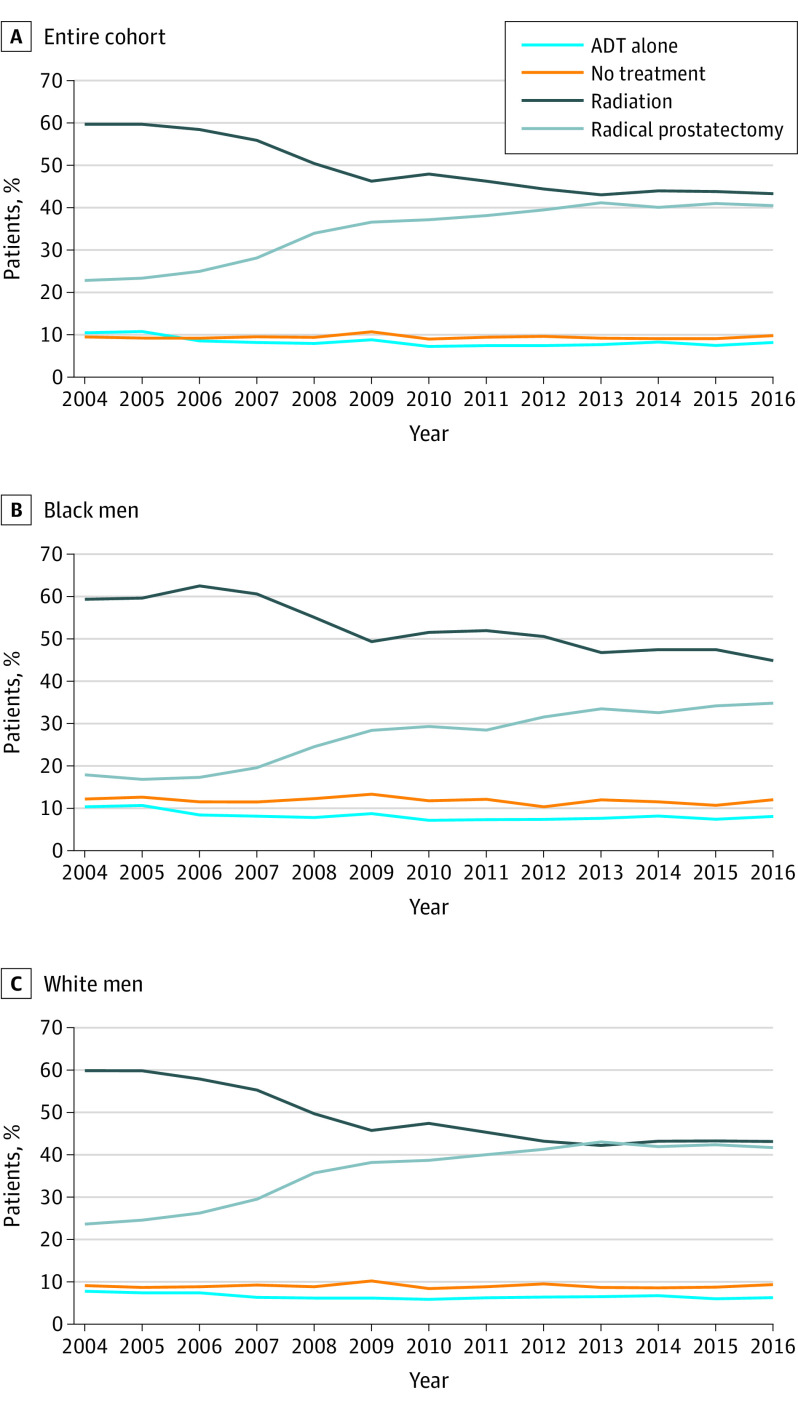

The proportional rates of high-risk prostate cancer increased from 11.8% to 20.4% (P < .001). The proportion of men undergoing prostatectomy increased from 22.8% to 40.5% (P < .001; Figure, A). Conversely, the rates of radiotherapy decreased from 59.7% to 43.3% (P < .001). External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) with a brachytherapy boost was used in 12.6% of men undergoing radiotherapy. Consistent with data presented in part A of the Figure, the odds of undergoing prostatectomy increased from 2004 to 2013 and remained consistent through 2016 (odds ratio, 2.34 [95% CI, 2.12-2.48]; P < .001). This trend was also observed among black men (Figure, B). The multivariable analysis appears in the Table.

Figure. Trends in Prostate Cancer Treatment From 2004-2016.

ADT indicates androgen deprivation therapy.

Table. Multivariable Logistic Regression for Association of Patient Characteristics With Radical Prostatectomy.

| No. (%) of Patients | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year of diagnosis | |||

| 2004 | 13 030 (6.1) | 1 [Reference] | |

| 2005 | 12 904 (6.0) | 1.01 (0.94-1.08) | .81 |

| 2006 | 13 864 (6.5) | 1.09 (1.02-1.17) | .01 |

| 2007 | 15 005 (7.0) | 1.29 (1.21-1.37) | <.001 |

| 2008 | 16 391 (7.6) | 1.70 (1.60-1.81) | <.001 |

| 2009 | 14 771 (6.9) | 2.02 (1.89-2.15) | <.001 |

| 2010 | 16 972 (7.9) | 2.03 (1.91-2.16) | <.001 |

| 2011 | 17 716 (8.2) | 2.15 (2.03-2.29) | <.001 |

| 2012 | 16 407 (7.6) | 2.32 (2.18-2.47) | <.001 |

| 2013 | 17 370 (8.1) | 2.51 (2.36-2.67) | <.001 |

| 2014 | 17 919 (8.3) | 2.52 (2.37-2.68) | <.001 |

| 2015 | 20 384 (9.5) | 2.66 (2.50-2.82) | <.001 |

| 2016 | 22 239 (10.4) | 2.72 (2.56-2.88) | <.001 |

| Age group, y | |||

| ≤50 | 5638 (2.6) | 1 [Reference] | |

| >50-60 | 41 690 (19.4) | 0.54 (0.50-0.58) | <.001 |

| >60-70 | 87 479 (40.7) | 0.33 (0.31-0.35) | <.001 |

| >70-80 | 63 683 (29.6) | 0.08 (0.08-0.09) | <.001 |

| >80 | 16 482 (7.7) | 0.01 (0.01-0.01) | <.001 |

| Gleason score | |||

| ≤6 | 24 016 (11.2) | 1 [Reference] | |

| 3 + 4 | 26 495 (12.3) | 1.19 (1.13-1.24) | <.001 |

| 3 + 5 | 8108 (3.8) | 0.96 (0.89-1.03) | .21 |

| 4 + 3 | 17 618 (8.2) | 0.92 (0.88-0.97) | .003 |

| 4 + 4 | 75 260 (35.0) | 0.58 (0.56-0.61) | <.001 |

| 4 + 5 | 45 409 (21.1) | 0.64 (0.61-0.67) | <.001 |

| 5 + 4 | 12 686 (5.9) | 0.57 (0.53-0.60) | <.001 |

| 5 + 5 | 5380 (2.5) | 0.37 (0.34-0.41) | <.001 |

| Prostate-specific antigen level, ng/mL | |||

| 0.1-4.0 | 17 694 (8.2) | 1 [Reference] | |

| 4.1-<10 | 75 003 (34.9) | 0.91 (0.87-0.95) | <.001 |

| 10-≤20 | 36 245 (16.9) | 0.60 (0.58-0.63) | <.001 |

| >20 | 86 030 (40.0) | 0.34 (0.32-0.36) | <.001 |

| Clinical stage | |||

| T1 | 115 436 (53.7) | 1 [Reference] | |

| T2 | 70 356 (32.7) | 0.81 (0.79-0.83) | <.001 |

| T3 | 26 847 (12.5) | 0.53 (0.52-0.56) | <.001 |

| T4 | 2333 (1.1) | 0.21 (0.18-0.24) | <.001 |

| Charlson-Deyo comorbidity index | |||

| 0 | 175 464 (81.6) | 1 [Reference] | |

| 1 | 31 103 (14.5) | 1.63 (1.58-1.68) | <.001 |

| >1 | 8405 (3.9) | 1.27 (1.20-1.35) | <.001 |

| Race | |||

| White | 170 198 (79.2) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Black | 34 667 (16.1) | 0.57 (0.55-0.59) | <.001 |

| Other | 10 107 (4.7) | 0.96 (0.91-1.01) | .14 |

| Geographic location | |||

| New England | 13 407 (6.2) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Mid Atlantic | 32 135 (14.9) | 1.36 (1.29-1.43) | <.001 |

| South Atlantic | 45 920 (21.4) | 1.13 (1.07-1.19) | <.001 |

| Central | |||

| East North | 41 440 (19.3) | 1.42 (1.35-1.50) | <.001 |

| East South | 16 174 (7.5) | 2.51 (2.36-2.67) | <.001 |

| West North | 18 242 (8.5) | 2.24 (2.11-2.38) | <.001 |

| West South | 13 188 (6.1) | 2.70 (2.53-2.88) | <.001 |

| Mountain | 8466 (3.9) | 2.04 (1.90-2.19) | <.001 |

| Pacific | 26 000 (12.1) | 1.73 (1.64-1.83) | <.001 |

| Facility type | |||

| Community | 19 183 (8.9) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Academic | 79 248 (36.9) | 2.57 (2.45-2.69) | <.001 |

| Comprehensive | 89 912 (41.8) | 1.72 (1.64-1.80) | <.001 |

| Integrated | 26 629 (12.4) | 2.27 (2.16-2.39) | <.001 |

| Type of insurance coverage | |||

| Private | 80 164 (37.3) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Medicare, Medicaid, or other government | 127 452 (59.3) | 0.64 (0.62-0.66) | <.001 |

| Uninsured | 4148 (1.9) | 0.62 (0.57-0.67) | <.001 |

| Unknown | 3208 (1.5) | 0.52 (0.47-0.57) | <.001 |

| Income quartile | |||

| 1 (lowest) | 40 791 (19.0) | 1 [Reference] | |

| 2 | 46 970 (21.8) | 1.09 (1.05-1.14) | <.001 |

| 3 | 50 429 (23.5) | 1.11 (1.07-1.16) | <.001 |

| 4 | 76 782 (35.7) | 1.12 (1.07-1.17) | <.001 |

| No high school diploma, % | |||

| <7 | 56 837 (26.4) | 1.38 (1.32-1.44) | <.001 |

| 7-12.9 | 61 388 (28.6) | 1.19 (1.14-1.23) | <.001 |

| 13-20.9 | 53 776 (25.0) | 1.06 (1.02-1.09) | .003 |

| ≥21 | 42 971 (20.0) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Distance, km | |||

| ≤96 | 193 848 (90.2) | 1 [Reference] | |

| 96-192 | 11 589 (5.4) | 2.53 (2.40-2.67) | <.001 |

| >192 | 9535 (4.4) | 2.53 (2.39-2.67) | <.001 |

| Population type | |||

| Metropolitan | 177 270 (82.5) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Rural | 4710 (2.2) | 0.81 (0.75-0.88) | <.001 |

| Urban | 32 992 (15.3) | 0.90 (0.87-0.94) | <.001 |

Discussion

Prostatectomy rates increased from 22.8% in 2004 to 40.5% in 2016, nearly equaling radiotherapy rates by 2016. Randomized data comparing modalities do not and likely will not exist in the foreseeable future to determine optimal treatment. The ProtecT trial compared prostatectomy vs radiotherapy and showed no difference in prostate-cancer specific mortality, but did not include a significant number of patients with high-risk prostate cancer.1 The Prostate Advances in Comparative Evidence trial (NCT01584258) compares prostatectomy vs radiotherapy, but only includes patients with low-risk and intermediate-risk cancer.

Population-based and institutional studies report conflicting results. Boorjian et al2 showed improved all-cause mortality with prostatectomy compared with EBRT. Kishan et al3 reported improved prostate-cancer specific mortality among men with Gleason score 9-10 treated with EBRT and a brachytherapy boost vs EBRT or prostatectomy; there was no difference between EBRT and prostatectomy. Our study showed limited use of the brachytherapy boost in patients with high-risk disease.

The increase in prostatectomies may reflect increasing acceptance of population-based data suggesting superiority of prostatectomy.2 The increasing use of robotic approaches suggests urologists and patients may regard prostatectomies safer than previous techniques. Conversely, a decrease in radiotherapy may reflect reluctance toward recommended androgen deprivation therapy with radiotherapy.

Demographic and socioeconomic factors were associated with treatment selection for patients with high-risk prostate cancer. Black men were less likely than white men to undergo prostatectomy, which is consistent with previous studies, but our findings suggest this gap has improved over time.4 Men with private insurance were more likely to undergo prostatectomy. Higher income, private insurance, and treatment at an academic facility were found to be associated with use of robotic prostatectomy.5 Thus, the differential use of prostatectomy may reflect limited access to high-volume centers and disproportionate reimbursement for robotic techniques.

Men may prefer prostatectomy given the treatment burden of radiotherapy, which may change with shortened schedules.6 Prostatectomy rates have doubled since 2004 without guideline evidence suggesting its superiority. Trials are needed to guide optimal care. The findings of this study are limited by its retrospective nature.

eFigure. Flow Diagram of Patients Included for Analysis

References

- 1.Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al. ; ProtecT Study Group . 10-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(15):1415-1424. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boorjian SA, Karnes RJ, Viterbo R, et al. . Long-term survival after radical prostatectomy versus external-beam radiotherapy for patients with high-risk prostate cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(13):2883-2891. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kishan AU, Cook RR, Ciezki JP, et al. . Radical prostatectomy, external beam radiotherapy, or external beam radiotherapy with brachytherapy boost and disease progression and mortality in patients with Gleason score 9-10 prostate cancer. JAMA. 2018;319(9):896-905. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmid M, Meyer CP, Reznor G, et al. . Racial differences in the surgical care of Medicare beneficiaries with localized prostate cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(1):85-93. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.3384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maurice MJ, Kim SP, Abouassaly R. Current status of prostate cancer diagnosis and management in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(11):1505-1507. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.1785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahase SS, D’Angelo D, Kang J, Hu JC, Barbieri CE, Nagar H. Trends in the use of stereotactic body radiotherapy for treatment of prostate cancer in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1920471. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Flow Diagram of Patients Included for Analysis