Abstract

This paper provides early evidence of the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on minority unemployment in the United States. In the first month following March adoptions of social distancing measures by states, unemployment rose to 14.5% but a much higher 24.4% when we correct for potential data misclassification noted by the BLS. Using the official definition, unemployment in April 2020 among African-Americans rose by less than what would have been anticipated (to 16.6%) based on previous recessions, and the long-term ordering of unemployment across racial/ethnic groups was altered with Latinx unemployment (18.2%) rising for the first time to the highest among major groups. Difference-in-difference estimates confirm that the initial gap in unemployment between whites and blacks in April was not different than in periods prior to the pandemic; however, the racial gap expanded as unemployment for whites declined in the next two months but was largely stagnant for blacks. The initially large gap in unemployment between whites and Latinx in April was sustained in May and June as unemployment declined similarly for both groups. Non-linear decompositions show a favorable industry distribution partly protected black employment during the early stages of the pandemic, but that an unfavorable occupational distribution and lower average skills levels placed them at higher risk of job losses. An unfavorable occupational distribution and lower skills contributed to a sharply widened Latinx-white unemployment gap that moderated over time as rehiring occurred. These findings of disproportionate impacts on minority unemployment raise important concerns regarding lost earnings and wealth, and longer-term consequences of the pandemic on racial inequality in the United States.

Keywords: Unemployment, Inequality, Labor, Race, Minorities, COVID-19, Coronavirus, Shelter-in-place, Social distancing

Highlights

-

•

In April 2020, unemployment rose to 14.5 percent (a higher 24.4 percent when potential data misclassification are fixed).

-

•

Unemployment in April 2020 among African-Americans rose by less than would have been anticipated (to 16.6 percent) based on previous recessions.

-

•

Long-term PO Ordering of unemployment across groups was altered with Latinx unemployment (18.2 percent) rising for the first time to the highest across groups.

-

•

The racial gap expanded as unemployment for whites declined in May and June but was largely stagnant for blacks.

-

•

The large gap in unemployment between whites and Latinx in April was sustained in May and June as unemployment declined similarly for both groups.

1. Introduction

The sudden outbreak of COVID-19 has affected the entire world. To slow the spread of the disease governments have enforced social distancing restrictions that have shut down businesses and laid off workers in jobs and industries deemed non-essential and severely reduced demand. The effects on the economy are readily observed through a tumultuous stock market, surge in unemployment insurance claims, and shuttering of store fronts across the country. This analysis focuses on the pressing question of whether these effects are being felt differently by race. Of special concern, African-Americans and Latinx might be especially vulnerable to negative economic shocks such as layoffs from COVID-19 because of limited savings and wealth, furthering long-term racial inequality in our country (Canilang et al., 2020).

A major source of inequality, the unemployment rate among blacks in the United States has been roughly double that of whites for decades. For example, over the past four decades, the average rate of unemployment was 11.7% for blacks versus 5.4% for whites. Historical analyses indicate that the 2:1 ratio of black-to-white unemployment rates first emerged in the 1950s (Fairlie and Sundstrom, 1997, Fairlie and Sundstrom, 1999). In his classic study of black unemployment, Freeman (1973) concluded that the relative movement of black and white unemployment rates over the business cycle supports “the widely asserted last in, first out pattern of black employment over the cycle.” Later analyses focusing on unemployment transitions have also found blacks to be the first fired as the business cycle weakens, but not necessarily the last hired (Couch and Fairlie, 2010). Blacks are also more likely to leave the labor force when exiting employment than whites. The Great Recession also disproportionately impacted minority unemployment, and recent research shows that Latinx have higher unemployment rates and greater cyclical sensitivity than whites (Couch et al., 2018; Hoynes et al., 2012; Orrenius and Zavodny, 2010).1

In this paper, we explore how COVID-19 affected minority unemployment. We consider two main questions. First, we examine whether COVID-19 disproportionately impacted blacks and Latinx relative to whites. In light of the well documented “first fired” pattern and persistently higher unemployment among blacks, we might expect to see unemployment rise by twice as much for blacks as whites, and Latinx unemployment to lie between the two groups. But, this COVID-19 related downturn is different than previous recessions due to state government mandated business closures and might result in different new disproportionate impacts by race that a priori cannot be theoretically ordered. Second, we explore how COVID-19 has differentially affected unemployment across job and skill types that may drive racial disparities in unemployment. Did the industries, occupations and skill levels of white workers insulate them from job losses due to shelter-in-place restrictions, or were minorities more likely to be employed in essential jobs? Did the ability to work from home or exposure to disease in the workplace play an important role in cross-group impacts?

To explore these questions, we examine Current Population Survey (CPS) microdata from April through June of 2020. April 2020 represents the first month fully capturing immediate impacts of COVID-19 policy mandates and subsequent months show labor market responses to the ongoing pandemic. We compare impacts of COVID-19 on black and Latinx unemployment relative to February 2020, longer trends in unemployment, and the Great Recession. Our analysis reveals that even though black unemployment jumped to 16.6% in April, blacks were not initially disproportionately impacted by COVID-19 compared to whites and previous months. However, as disproportionate rehiring occurred among whites in May and June, difference-in-difference estimates indicate a widening of the black-white unemployment gap ranging from 2.5 to 2.75 percentage points. Turning to an upper-bound measure of unemployment based on BLS concerns about misclassifications of workers, we find a black unemployment rate that shot up to 29.8%, 8.5 percentage points higher than for whites. Using this measure, difference-in-difference estimates provide evidence of larger disproportionate impacts on the black-white gap in unemployment from COVID-19 emerging in April and continuing in subsequent months.

The impacts on Latinx are also alarming. The unemployment rate among Latinx increased in April 2020 to 18.2%, or 29.5%, using the upper-bound measure. Both measures indicate considerably higher unemployment than for whites and rates higher than or directly comparable to black levels (for the first time). The unemployment rate decreased for Latinx as rehiring occurred. Nonetheless, difference-in-difference estimates provide consistent evidence across all time periods and measures used of disproportionate increases in Latinx unemployment relative to whites due to COVID-19. The regression adjusted gaps in Latinx unemployment relative to whites are also consistently larger than for blacks.

To explore the second question regarding whether differential effects from COVID-19 on unemployment across job and skill types contribute to racial disparities, we estimate non-linear decompositions to identify the factors that placed minorities at more or less of a risk of losing jobs during the early stages of the pandemic. There are four main findings from the analysis. First, we find that a slightly favorable industry distribution partly protected black employment during the early stages of the pandemic. Second, we find that an unfavorable occupational distribution and lower skills explain why Latinx experienced the largest gaps in unemployment due to COVID-19. Third, we find that occupational and educational differences also contribute to why blacks have higher unemployment rates than whites, but to a lesser extent than for Latinx. Finally, we find that blacks and Latinx were less likely to have jobs that allowed for work at home which contributed somewhat to higher unemployment relative to whites.

The findings from our paper and its first version (Couch et al., 2020) contribute to a rapidly emerging literature on early-stage COVID-19 impacts on the labor market. Kahn et al. (2020) use data from Burning Glass and initial Unemployment Insurance claims and find that job postings declined by 30% and that with the exception of employment in essential industries all states and sectors experienced sharp increases in unemployment. Using payroll data Cajner et al. (2020) find that private sector payrolls shrank by 22% from mid-February to mid-April. Those findings are echoed in early papers by Bick and Blandin (2020) and Coibion et al. (2020) who make use of survey data they collected at a high frequency to gain rapid indications of labor market behavior. Montenovo et al. (2020) use CPS data from March and April of 2020 and construct indices of job characteristics expected to be related to job loss such as ability to work remotely and importance of face-to-face contact. They find that these factors as well as occupation distributions help explain differences in emerging unemployment rates across a wide range of groups.

Early analyses have also begun to try and distinguish between the employment effects of closure policies and disease related fears in reducing demand. Goolsbe and Syverson (2020) use information on individual foot traffic to businesses based on cell phone data and find that county-level closures account for about 7 percentage points of the overall decline in foot traffic but COVID-19 cases account for 30 percentage points of the total decline. Bartik et al. (2020) similarly conclude after examining the relationship between policies, Google searches, and Safegraph data on business visitations that “overall patterns have more to do with broader health and economic concerns affecting product demand and labor supply rather than with shut-down or re-opening orders themselves.” In contrast, Gupta et al. (2020) find that state social distancing policies had a large effect on unemployment. Our paper builds on these previous studies on early effects of the pandemic by providing a detailed analysis of unemployment among minorities driven by the spread of the coronavirus in the United States and early effects of COVID-19 on unemployment beginning with April and extending through the next two months of the pandemic using CPS data.2

2. Data

2.1. Current Population Survey (CPS)

The data used in the analysis are the Basic Monthly Files from the CPS, the source of the official household-based survey measure of unemployment. These surveys, conducted monthly by the U.S. Bureau of the Census and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, are representative of the civilian non-institutional population and contain observations for more than 130,000 people.

The impact of the coronavirus on the U.S. labor market began to be felt from April forward (see Couch et al., 2020 for more details on timing and data). Thus, we focus on April–June data in the CPS.

As COVID-19 spread individual states mandated closure of non-essential businesses. We use Delaware's criteria to determine whether an industry is essential in the CPS data at the 4-digit industry level (https://coronavirus.delaware.gov/resources-for-businesses/). The Delaware State list is the most comprehensive we could find and follows the same industry codes as the CPS (NAICS). Also, many people have been performing their jobs from home. Dingel and Neiman (2020) develop an index of the ability of an occupation to be performed remotely from a set of 15 questions in O*NET (Occupational Information Network) which we use with 4-digit CPS occupation codes. Similarly, we consider the exposure of individuals to disease or infection in their workplace as a possible explanatory factor for gaps in unemployment making use of the index developed by Baker et al. (2020). Their index is also based on an O*NET question, “How often does your current job require you be exposed to diseases or infections?” which is normalized as a Z-score.

3. Disparities in unemployment

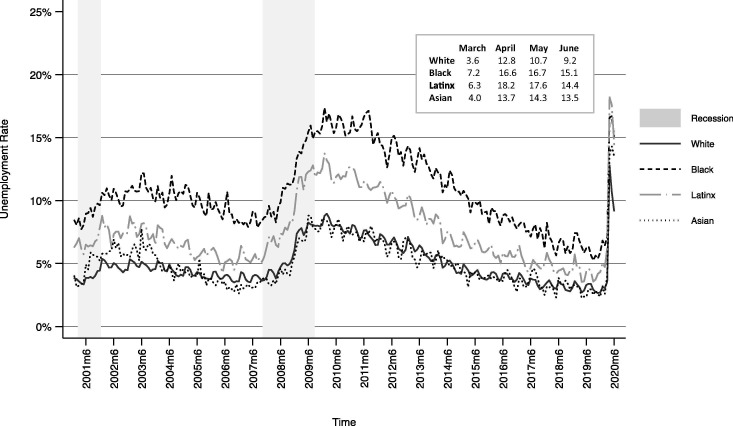

Fig. 1 displays unemployment rates by race from January 2001 to June 2020. The unprecedented jumps in unemployment rates for all racial groups starting in April 2020 are clear. To focus on this period, Table 1 Panel A reports estimates of unemployment rates by race for April through June of 2020 and other time periods for comparison. The unemployment rate was extremely high in April 2020 hitting 14.5%, the highest level since the Great Depression and roughly 5 percentage points greater than during the Great Recession. The unemployment rate hit 16.6% for African-Americans and 12.8% for whites (measured as white non-Hispanic throughout). The highest level was for Latinx at 18.2%, the highest rate on record for this group. Asians experienced an unemployment rate of 13.7%.

Fig. 1.

Unadjusted unemployment rate by race, January 2001 to June 2020.

Table 1.

Unemployment rates by race around shelter-in-place regulations.

| Black-White |

Latinx-White |

Asian-White |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Black | Gap | Latinx | Gap | Asian | Gap | Total | |

| Panel A. Unemployment rate | ||||||||

| June 2020 | 9.2% | 15.1% | 5.9% | 14.4% | 5.2% | 13.5% | 4.3% | 11.2% |

| May 2020 | 10.7% | 16.7% | 6.0% | 17.6% | 6.9% | 14.3% | 3.6% | 13.0% |

| April 2020 | 12.8% | 16.6% | 3.8% | 18.2% | 5.4% | 13.7% | 0.9% | 14.5% |

| March 2020 | 3.6% | 7.2% | 3.6% | 6.3% | 2.7% | 4.0% | 0.5% | 4.6% |

| February 2020 | 3.1% | 6.4% | 3.4% | 4.7% | 1.7% | 2.6% | −0.5% | 3.8% |

| January 2020 | 3.1% | 6.8% | 3.7% | 5.1% | 2.0% | 3.2% | 0.1% | 4.0% |

| Jan 2017 - Dec 2019 | 3.3% | 6.8% | 3.5% | 4.6% | 1.4% | 3.2% | −0.1% | 4.0% |

| Dec 2007 - June 2009 (GR) | 5.6% | 11.4% | 5.8% | 8.7% | 3.1% | 5.1% | −0.6% | 6.8% |

| New unemployment | ||||||||

| June 2020 (4 months back) | 8.2% | 12.8% | 4.6% | 12.7% | 4.5% | 12.1% | 3.9% | 9.9% |

| May 2020 (3 months back) | 9.7% | 14.5% | 4.9% | 15.7% | 6.1% | 12.8% | 3.2% | 11.6% |

| April 2020 (2 months back) | 11.5% | 14.3% | 2.8% | 16.3% | 4.8% | 12.2% | 0.7% | 12.9% |

| February 2020 (2 months back) | 1.7% | 3.3% | 1.6% | 2.6% | 0.9% | 1.3% | −0.3% | 2.0% |

| Sample sizes | ||||||||

| June 2020 | 31,937 | 4116 | 5237 | 2809 | 45,334 | |||

| May 2020 | 32,976 | 4267 | 5417 | 2935 | 46,832 | |||

| April 2020 | 33,631 | 4423 | 5696 | 3065 | 48,190 | |||

| March 2020 | 35,651 | 4929 | 6385 | 3263 | 51,677 | |||

| February 2020 | 39,983 | 5715 | 7898 | 3717 | 58,982 | |||

| January 2020 | 39,806 | 5594 | 7652 | 3570 | 58,270 | |||

| Jan 2017 - Dec 2019 | 1,510,998 | 216,965 | 277,756 | 131,905 | 2,201,116 | |||

| Dec 2007 - June 2009 (GR) | 962,486 | 119,825 | 139,191 | 61,269 | 1,316,170 | |||

| Panel B. Unemployment rate upper-bound measure | ||||||||

| June 2020 | 14.7% | 23.2% | 8.5% | 20.8% | 6.2% | 20.6% | 5.9% | 17.4% |

| May 2020 | 18.0% | 26.6% | 8.6% | 26.0% | 8.0% | 25.3% | 7.4% | 21.2% |

| April 2020 | 21.3% | 29.8% | 8.5% | 29.5% | 8.1% | 25.6% | 4.3% | 24.4% |

| February 2020 | 5.9% | 11.0% | 5.1% | 7.8% | 1.9% | 5.7% | −0.2% | 7.0% |

| Jan 2017 - Dec 2019 | 6.3% | 11.5% | 5.2% | 8.2% | 1.9% | 6.5% | 0.2% | 7.4% |

| Dec 2007 - June 2009 (GR) | 8.8% | 16.5% | 7.7% | 12.4% | 3.7% | 8.5% | −0.2% | 10.3% |

| Sample sizes | ||||||||

| June 2020 | 33,241 | 4471 | 5559 | 2967 | 47,576 | |||

| May 2020 | 34,498 | 4643 | 5777 | 3133 | 49,419 | |||

| April 2020 | 35,149 | 4847 | 6111 | 3257 | 50,868 | |||

| February 2020 | 40,977 | 5988 | 8152 | 3830 | 60,709 | |||

| Jan 2017 - Dec 2019 | 1,551,238 | 227,867 | 287,932 | 136,210 | 2,270,404 | |||

| Dec 2007 - June 2009 (GR) | 989,295 | 126,771 | 144,815 | 63,399 | 1,359,921 | |||

Notes: Calculated by author using CPS microdata. Estimates for the above race groups will not sum to totals because data are not presented for all races. New unemployment in Panel A is defined as newly unemployed with duration less than or equal to 2, 3, or 4 months and removing prior unemployed (duration more than 2, 3, or 4 months) from the sample. The upper-bound unemployment rate in Panel B is a measure of unemployment that adds those employed but absent from work (due to other reasons) and those not in the labor force who wanted a job.

As shown in Panel A, the comparison to February 2020, the last month before statewide social distancing measures, is striking. The unemployment rate was at or near long-term lows of 6.4% and 4.7% for blacks and Latinx. Whites had an unemployment rate of 3.1% and Asians 2.6%. Over the two-month time period subsequently impacted by the coronavirus, the unemployment rate increased by 9.7 percentage points for whites and only slightly more (by 10.2 percentage points) for blacks. This contrasts sharply with previous recessions in which black unemployment rates increased much more in percentage points than for whites, maintaining a fairly constant 2:1 historical ratio relative to whites.

The unemployment rate increased by 13.5 percentage points for Latinx from February to April 2020, the largest increase for any group. Asians also experienced a surprisingly large increase in unemployment (11.1 percentage points) across these months. Comparisons to January 2020 reveal similar sharp increases in unemployment rates. Interestingly, from January to April 2020, the increase in black and white unemployment rates were almost identical.

Examining unemployment over the prior three years is also useful for gauging the scale of COVID-19 impacts. In the period from January 2017 to December 2019, we find that black unemployment at 6.8% was 3.5 percentage points higher than for whites (again displaying the roughly 2:1 ratio). Latinx unemployment was 4.6% which was 1.4 percentage points higher than the white rate.

Comparing what is happening due to COVID-19 and the previous recession is illustrative. In the Great Recession, black unemployment rates, at 11.4 percent, were 5.8 percentage points higher than for whites. Latinx unemployment rates were 8.7% (3.1 percentage points higher than white rates). In previous work, we find that the disproportionate increase in unemployment among blacks and Latinx in the Great Recession was due to increased job loss (instead of slower hiring rates), which is consistent with widely asserted “first fired” patterns (Couch and Fairlie, 2010; Couch et al., 2018).

In the subsequent months of May and June, some recovery has occurred in the labor market particularly among whites and Latinx. In comparison to April, white unemployment declined by 3.6 percentage points (or 28%) to 9.2%. For Latinx, the reduction in unemployment was 3.8 percentage points (or 21%) to 14.4%. The experience of blacks was different, however. By June, unemployment for blacks remained at 15.1% in comparison to 16.6% in April. Among Asians, unemployment in June (13.5%) was little changed from the level of 13.7% in April. Thus, the initial recovery was most pronounced among whites and Latinx. But, even with these slight improvements in employment the high levels of unemployment are likely to result in substantial earnings losses (U.S. Census, 2020).

Returning to Fig. 1, the longer-term patterns in unemployment are clear. Black and Latinx unemployment rates follow white unemployment rates rising and falling cyclically, and the gaps become larger in downturns and smaller in growth periods. The gaps between black and white unemployment historically are larger than for Latinx versus whites. In April 2020, COVID-19 resulted in an enormous jump in unemployment rates for all groups. Extremely rapid job loss of this scale is unprecedented. The pattern is also anomalous because the unemployment rate for the Latinx group in April (18.2%) exceeded that of blacks (16.6%) for the first time.

The comparison of racial differences in unemployment rates (gaps) in April 2020 to previous time periods creates a simple difference-in-difference estimate of the disproportionate impacts of COVID-19 on minority unemployment rates. The black-white gap in April 2020 shown in Table 1 Panel A is 3.8 percentage points. This is only slightly larger than the gaps of 3.4 percentage points in February, 3.7 percentage points in January, and 3.5 percentage points from 2017 to 2019. The difference then between the black-white unemployment gap in April versus these prior periods is small. Looking back further to the most recent recession for comparison, the black-white gap in the Great Recession was much higher at 5.8 percentage points. Blacks experienced a smaller increase in their unemployment relative to whites in April 2020 compared to what happened in the Great Recession. This is an important break from prior cyclical behavior of unemployment rates.

In sharp contrast to these patterns, Latinx experienced a much worse impact on unemployment in April 2020 as seen in Table 1 Panel A. The Latinx-white unemployment gap in February was 1.7 percentage points. The gap soared to 5.4 percentage points in April 2020. The COVID-19 Latinx-white gap immediately surpassed its average value in the Great Recession (3.1 percentage points).

In the subsequent months, through June, the gap in unemployment widened considerably between blacks and whites (from 3.8% in April to 5.9% in June) primarily due to more rapid reductions in white unemployment. The gap between Asians and whites also widened considerably from 0.9% in April to 4.3% in June primarily because of little reduction in unemployment among Asians. The gap for Latinx was similar in April (5.4%) and June (5.2%) because as a group, unemployment for the Latinx fell by about the same amount as for whites. Thus, the initial impact of COVID-19 fell most heavily on Latinx but their situation improved as businesses reopened along with whites. Unemployment was little changed for blacks and Asians so their experiences have worsened over time relative to whites.

3.1. Alternative measures of unemployment

Table 1 Panel A also reports estimates of unemployment rates for those newly unemployed at the time of the April 2020 CPS survey (defined as within the past two months using the question on duration of unemployment and thus after mid-February). Using this measure the estimated gaps are similar to those calculated using the standard measure of unemployment. However, another observation that can be drawn from these data is that the majority of the unemployed from April to June became unemployed after mid-February (e.g. 14.3% of blacks in April were newly unemployed relative to the 16.6% total).

The BLS released warnings about the March and April 2020 counts of unemployment indicating they may possibly be too low. In the reports (BLS April, 2020, p. 4) they note that “workers who indicate that they were not working during the entire reference week due to efforts to contain the spread of the coronavirus should be classified as unemployed on temporary layoff, whether or not they are paid for the time they were off work.” But BLS found that many of these workers were classified (ibid) as “employed but absent from work.”

Another concern noted by the BLS was that the number of people not in the labor force (NILF) reporting they want a job nearly doubled in April. This group could also be added to the unemployment numbers to gauge the impact of the coronavirus on nonemployment. For a thorough discussion of these issues see Couch et al. (2020).

To address these concerns, we create a second measure of unemployment incorporating these two groups noted by the BLS. This “upper-bound” measure of unemployment adds both the group that reported being employed and paid but absent from work due to other reasons and those NILF who wanted a job.3

Table 1 Panel B reports these alternate estimates of unemployment. In February 2020, the official unemployment rate was 3.8% and the alternate upper-bound unemployment rate was 7.0%. In April 2020, however, the national unemployment rate was 14.5% and the upper-bound unemployment rate was 24.4%. One view of this alternate measure, which more broadly reflects labor market impacts, is that unemployment at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic was about at the peak seen in the Great Depression.

For this alternate upper-bound measure we find that blacks had an unemployment rate of 29.8%, 8.5 percentage points higher than the white rate. This black-white gap is larger than it was in February 2020 (5.1%) or in the three years from 2017 to 2019 (5.2%) suggesting that blacks experienced a disproportionate impact from COVID-19 (relative to whites) of about 3 percentage points compared to recent months. In the Great Recession the upper-bound unemployment rate was 7.7 percentage points higher for blacks than whites. The gap observed in April for blacks relative to whites has not narrowed in subsequent months. While the current gap in unemployment between blacks and whites is similar to that observed in the Great Recession using this alternate measure of unemployment, it is important to bear in mind that the analysis examines the first 3 months of the crisis.

For the Latinx group, the upper-bound unemployment rate is 29.5% in April of 2020, 8.1 percentage points higher than for whites. This large differential contrasts with much smaller gaps in February (1.9 percentage points), or the previous three-year time period (1.9 percentage points). Thus, the gap widened by about 6 percentage points in comparison. It also contrasts with a smaller gap in the Great Recession of 3.7 percentage points. Using this alternate measure, the unemployment experience of Latinx improved somewhat relative to whites through June with a narrowing of the racial gap to 6.2 percentage points. Nonetheless, with a June unemployment rate of 20.8% Latinx experienced an unambiguously large disproportionate impact from COVID-19 on unemployment.

3.2. Difference-in-difference estimates of COVID-19 impacts

To more formally test whether COVID-19 had disproportionate impacts on unemployment among minorities, we estimate the following regression for the probability of unemployment:

| (3.1) |

where U it equals 1 if the individual is unemployed in the survey month and 0 otherwise, COVID m is a dummy variable for each post COVID month (e.g. m = 2 for April 2020), X it includes individual, regional and job characteristics, λ t are month fixed effects to control for seasonality, θ t are year fixed effects and/or time trends, and ε it is the error term. March 2020 is included in the sample, but not reported in the tables because of potentially misleading estimates associated with a partially COVID-19 impacted month.4 The parameters of interest are the δ m j, which capture the disproportionate effect estimates of COVID-19 on minority unemployment for each follow up month, m, and each minority group, j. All specifications are estimated with OLS using CPS sample weights and robust standard errors.

Table 2 reports estimates of Eq. (3.1) that vary the sample period. Specification 1 includes observations from February through June 2020. Specification 2 uses data from January 2017 to June 2020. Specification 3 similarly spans December 2007 to June 2020, and includes a full set of additional group interactions for the Great Recession for comparison. Specifications 1–3 make use of the official unemployment definition while Specifications 4–6 use the expanded upper-bound measure. The regressions also control for individual, job and geographic characteristics as available for different samples. The base specification includes a time trend and estimates are robust to its removal, adding a quadratic, and permutations of month and year fixed-effects (results are available on request).

Table 2.

Unemployment probability regressions.

| Unemployed |

Unemployed (upper-bound measure) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

|

| Sample period | Feb 2020 - June 2020 | Jan. 2017 - June 2020 | Dec. 2007 - June 2020 | Feb 2020 - June 2020 | Jan. 2017 - June 2020 | Dec. 2007 - June 2020 |

| Black | 0.0171*** | 0.0227*** | 0.0208*** | 0.0185*** | 0.0235*** | 0.0235*** |

| (0.0038) | (0.0006) | (0.0006) | (0.0039) | (0.0006) | (0.0006) | |

| Latinx | −0.0113*** | −0.0030*** | −0.0113*** | −0.0169*** | −0.0051*** | −0.0084*** |

| (0.0028) | (0.0005) | (0.0004) | (0.0030) | (0.0005) | (0.0005) | |

| Asian | −0.0041 | −0.0015*** | −0.0013** | 0.0012 | −0.0018*** | −0.0014** |

| (0.0032) | (0.0005) | (0.0005) | (0.0036) | (0.0006) | (0.0006) | |

| COVID_April | 0.1011*** | 0.1061*** | 0.1066*** | 0.1417*** | 0.1455*** | 0.1438*** |

| (0.0023) | (0.0023) | (0.0022) | (0.0025) | (0.0025) | (0.0025) | |

| COVID_May | 0.0783*** | 0.0846*** | 0.0838*** | 0.1056*** | 0.1110*** | 0.1075*** |

| (0.0021) | (0.0021) | (0.0021) | (0.0023) | (0.0023) | (0.0023) | |

| COVID_June | 0.0605*** | 0.0642*** | 0.0646*** | 0.0748*** | 0.0760*** | 0.0728*** |

| (0.0021) | (0.0020) | (0.0020) | (0.0022) | (0.0022) | (0.0021) | |

| COVID_April * Black | 0.0066 | 0.0073 | 0.0075 | 0.0182** | 0.0176** | 0.0177** |

| (0.0076) | (0.0068) | (0.0068) | (0.0078) | (0.0071) | (0.0071) | |

| COVID_April * Latinx | 0.0371*** | 0.0408*** | 0.0412*** | 0.0511*** | 0.0537*** | 0.0541*** |

| (0.0064) | (0.0060) | (0.0060) | (0.0066) | (0.0063) | (0.0063) | |

| COVID_April * Asian | 0.0145* | 0.0119* | 0.0120* | 0.0371*** | 0.0376*** | 0.0377*** |

| (0.0075) | (0.0071) | (0.0071) | (0.0084) | (0.0081) | (0.0081) | |

| COVID_May * Black | 0.0272*** | 0.0273*** | 0.0274*** | 0.0307*** | 0.0302*** | 0.0303*** |

| (0.0077) | (0.0069) | (0.0069) | (0.0077) | (0.0070) | (0.0070) | |

| COVID_May * Latinx | 0.0541*** | 0.0573*** | 0.0580*** | 0.0550*** | 0.0573*** | 0.0577*** |

| (0.0064) | (0.0060) | (0.0060) | (0.0065) | (0.0061) | (0.0061) | |

| COVID_May * Asian | 0.0419*** | 0.0386*** | 0.0391*** | 0.0653*** | 0.0651*** | 0.0653*** |

| (0.0078) | (0.0074) | (0.0074) | (0.0084) | (0.0081) | (0.0081) | |

| COVID_June * Black | 0.0256*** | 0.0268*** | 0.0268*** | 0.0228*** | 0.0232*** | 0.0233*** |

| (0.0075) | (0.0066) | (0.0066) | (0.0074) | (0.0065) | (0.0065) | |

| COVID_June * Latinx | 0.0353*** | 0.0382*** | 0.0395*** | 0.0335*** | 0.0348*** | 0.0355*** |

| (0.0060) | (0.0055) | (0.0055) | (0.0061) | (0.0055) | (0.0055) | |

| COVID_June * Asian | 0.0481*** | 0.0457*** | 0.0462*** | 0.0511*** | 0.0525*** | 0.0527*** |

| (0.0078) | (0.0074) | (0.0074) | (0.0080) | (0.0076) | (0.0076) | |

| Great recession * Black | 0.0214*** | 0.0181*** | ||||

| (0.0012) | (0.0011) | |||||

| Great recession * Latinx | 0.0146*** | 0.0139*** | ||||

| (0.0009) | (0.0009) | |||||

| Great recession * Asian |

−0.0032*** | −0.0033*** | ||||

| (0.0011) | (0.0012) | |||||

| Seasonality (months) controls | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Time trend | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effects | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| State fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sample size | 251,015 | 2,510,401 | 9,815,403 | 261,812 | 2,592,256 | 3,952,177 |

Notes: The dependent variable in Specification (1) to (3) is unemployment (0,1). The dependent variable in Specifications (4) to (6) is the upper-bound definition of unemployment which also includes those employed but absent from work (due to other reasons) and those not in the labor force who wanted a job. COVIDt is a dummy variable for the months beginning with April 2020. The Great Recession dummy equals 1 for the months December 2007 to June 2009 and 0 otherwise, and is also included in Specifications (4) and (6). For Specification (6), because of data availability in creating the upper-bound measure of unemployment, the sample is limited to December 2007 through June of 2009 and January 2017 through June 2020. All specifications include controls for gender, family structure, education level, years of potential work experience and its square, essential industry indicator, major industry and occupation. All specifications are estimated using CPS sample weights and robust standard errors. Standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

The results in Specification 1 show that COVID-19 across the months of April, May and June resulted in 10.1, 7.8 and 6.0 percentage point increases in unemployment that are statistically significant. For blacks, COVID did not meaningfully widen the unemployment gap in April compared to February; however, in May and June increases of 2.7 and 2.6 percentage points are estimated. Latinx experienced a large and statistically significant increase in unemployment relative to whites in April, May and June of 3.7, 5.4, and 3.5 percentage points. Asians exhibit an increased gap in unemployment over April, May and June of 1.5, 4.2 and 4.8. The results in Specifications 2 and 3 extending the sample back to January 2017 and then to December of 2007 while adding year fixed-effects, a time trend and month of year dummies yield similar results.

Specification 3 also provides a comparison of post-COVID racial gaps to those in the Great Recession. The comparison is especially interesting for blacks. The average black-white unemployment gap in the Great Recession was 2.1 percentage points, but only three quarters of a percentage point in April (the difference is statistically significant). Thus, the black-white gap in unemployment is smaller in the first post-COVID month than during the Great Recession. The finding changes quickly, however, as the COVID impacts in May and June are not statistically distinguishable from the Great Recession. For Latinx and Asians, the comparison reveals a different finding with both groups experiencing larger gaps in unemployment post-COVID (and statistically significant) than in the Great Recession. These tests are available on request from the authors.

We also estimate difference-in-difference models using the upper-bound unemployment measure in Specifications 4–6. We note, however, that we cannot include occupation and industry controls for all observations because they are not collected for more than 90% of those out of the labor force. The impact of COVID-19 for all groups in Specification 4 using February through June data is 14.2, 10.6, and 7.5 percentage points across the months of April, May and June. Although these levels are higher, the change over time in the black-white unemployment gap due to COVID-19 is estimated to be 1.8%, 3.1% and 2.3% in the months of April, May and June. Similar estimates are reported in Specifications 5 and 6 as the sample period is extended.

Using the alternate definition of employment for Latinx, the estimated increase in the unemployment gap due to COVID-19 in April ranges from 5.1 to 5.4 percentage points across Specifications 4–6. In May, the estimates are similar, but in June, they decline somewhat, ranging from 3.3 to 3.6 percentage points. Similarly, the gap due to COVID-19 is about 3.8 percentage points for Asians in April across specifications 4 to 6. The gap between Asian and white unemployment is 6.5 percentage points in May and ranges from 5.1 to 5.3 percentage points in June. Thus, using either definition of unemployment, Latinx appear to be most impacted by COVID-19 in April. However, by June, Asians appear to be most impacted. The change in the unemployment gap for blacks due to COVID-19 policy mandates and demand shifts was muted in April in comparison to prior downturns but then rose to levels similar to those in the Great Recession.

4. Job and skill-level risk factors for COVID-19 impacts

To investigate whether various job, skill and region characteristics place minorities at differential risk of unemployment in general and during COVID-19, we examine distributions in these characteristics by race and then perform decompositions that identify which factors are most important. Table 3 presents racial group distributions prior to the pandemic and the national unemployment rate averaged from April to June 2020 for several risk factors.

Table 3.

Risk factors for unemployment from COVID-19.

| Risk factor (Feb.2017 – Feb 2020) |

April 2020 to June 2020 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black | Latinx | Asian | White | Total | National unemployment rate | |

| Essential | ||||||

| Nonessential industry | 16.5% | 15.2% | 15.9% | 15.5% | 15.7% | 27.2% |

| Essential industry | 83.5% | 84.9% | 84.1% | 84.6% | 84.3% | 10.4% |

| Education | ||||||

| High school dropout | 7.9% | 23.7% | 6.1% | 4.9% | 8.6% | 21.6% |

| High school graduates | 31.5% | 32.1% | 17.0% | 24.6% | 26.3% | 16.1% |

| Some college | 32.5% | 25.5% | 18.3% | 28.4% | 27.9% | 14.8% |

| College graduates | 18.3% | 13.3% | 32.8% | 26.9% | 23.8% | 9.3% |

| Graduate school | 9.8% | 5.3% | 25.7% | 15.2% | 13.4% | 5.6% |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 17.2% | 11.8% | 19.6% | 19.3% | 17.7% | 14.7% |

| Midwest | 16.2% | 9.5% | 11.9% | 26.9% | 21.5% | 13.1% |

| South | 57.2% | 39.1% | 23.7% | 34.0% | 37.0% | 11.2% |

| West | 9.5% | 39.6% | 44.8% | 19.8% | 23.8% | 14.0% |

| Experience | ||||||

| Potential experience (years) | 21.4 | 21.4 | 21.3 | 24.0 | 22.9 | |

| Less than median | 14.1% | |||||

| More than median | 11.4% | |||||

| Major industry (2-digit NAICS) | ||||||

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting | 0.4% | 2.7% | 0.4% | 1.7% | 1.6% | 5.0% |

| Mining | 0.2% | 0.6% | 0.23% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 12.0% |

| Construction | 3.8% | 12.9% | 2.6% | 7.0% | 7.2% | 12.2% |

| Manufacturing | 8.4% | 9.8% | 11.0% | 10.3% | 10.0% | 11.2% |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 12.7% | 13.2% | 11.8% | 13.1% | 13.0% | 14.2% |

| Transportation and utilities | 8.7% | 5.8% | 4.9% | 4.9% | 5.5% | 12.3% |

| Information | 1.7% | 1.3% | 2.3% | 2.0% | 1.8% | 12.1% |

| Financial activities | 5.7% | 5.0% | 7.8% | 7.4% | 6.7% | 5.5% |

| Professional and business services | 10.4% | 11.4% | 17.2% | 12.6% | 12.4% | 8.9% |

| Educational and health services | 27.1% | 16.5% | 21.2% | 23.1% | 22.4% | 10.0% |

| Leisure and hospitality | 10.4% | 12.4% | 10.3% | 8.2% | 9.5% | 33.6% |

| Other services | 4.3% | 5.5% | 6.1% | 4.7% | 4.9% | 17.9% |

| Public administration | 6.3% | 3.2% | 3.4% | 4.7% | 4.6% | 3.7% |

| Major occupation (2-digit NAICS) | ||||||

| Management, business, and financial occupations | 11.0% | 9.6% | 17.4% | 19.4% | 16.5% | 5.4% |

| Professional and related occupations | 19.3% | 12.5% | 34.2% | 25.5% | 23.0% | 8.1% |

| Service occupations | 24.3% | 24.1% | 16.6% | 14.2% | 17.5% | 23.1% |

| Sales and related occupations | 9.3% | 9.4% | 8.7% | 10.6% | 10.1% | 15.5% |

| Office and administrative support occupations | 13.4% | 10.9% | 8.9% | 11.2% | 11.3% | 11.7% |

| Farming, fishing, and forestry occupations | 0.3% | 2.3% | 0.3% | 0.6% | 0.8% | 9.5% |

| Construction and extraction occupations | 3.2% | 11.4% | 1.7% | 4.7% | 5.4% | 15.3% |

| Installation, maintenance, and repair occupations | 2.3% | 3.5% | 1.7% | 3.3% | 3.1% | 11.2% |

| Production occupations | 6.0% | 7.4% | 5.4% | 4.9% | 5.5% | 14.9% |

| Transportation and material moving occupations | 10.2% | 8.3% | 4.7% | 5.4% | 6.5% | 17.0% |

| Telework | ||||||

| Share of jobs that can be done at home | 32.1% | 24.4% | 43.5% | 41.7% | 37.4% | |

| Less than median | 15.9% | |||||

| More than median | 9.7% | |||||

| Health risk | ||||||

| Exposed to health risk index (Z-score) | 0.12 | −0.05 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.00 | |

| Less than median | 10.3% | |||||

| More than median | 15.5% | |||||

Notes: Calculated by author using CPS microdata based on February 2017 to February 2020. Sample includes all individuals in the labor force ages 16 and over. The last column shows the April to June national unemployment rate which includes all races.

Considering educational categories, the largest unemployment rates in April are among those with less than a high school education (21.6%) and high school graduates (16.1%). Latinx workers are heavily concentrated in these lower education levels as well as blacks, but to a lesser extent. Lower education levels placed blacks and especially Latinx at a greater risk of unemployment during the pandemic.

Being in an essential vs. non-essential industry should affect unemployment. Table 3 shows that although unemployment is concentrated among workers in non-essential industries (27.2%) there is little variation in the proportion employed in them across groups. Across major industry groups, the highest unemployment rate occurred in Leisure and Hospitality (33.6%) where Latinx have the largest prior concentration of employment (12.4%) although blacks and Asians also have relatively large concentrations. Similarly, rates of unemployment are high in Wholesale and Retail Trade (14.2%) and Construction (12.2%) and Latinx have the largest proportion employed in those industries. In areas like Public Administration and Educational and Health Services which have relatively low rates of unemployment (3.7% and 10%), blacks and whites have the largest relative concentrations.

Across occupations, the highest observed unemployment rate is for Service Occupations (23.1%). Blacks and Hispanics have the highest proportions (24.3% and 24.1% respectively) employed in Service occupations. Construction and Extraction Occupations also have a high unemployment rate of 15.3% since March. Latinx have the largest concentration (11.4%) in this occupation. For, the two categories with the lowest rates of unemployment, Management, Business and Financial Occupations (5.4%) and Professional and Related Occupations (8.1%), 44.9% of whites are employed in these two occupations but only 22.1% of Latinx and 30.3% of Blacks.

Two additional risk factors are regional distributions and potential work experience (another measure of skills). Racial groups are concentrated in different regions with 57% of blacks living in the South, nearly half of all Asians living in the West, and 40% of Latinx living in the West. Unemployment in the South is 2 to 4 percentage points lower than in other regions. In terms of potential work experience (age – year of school leaving), minority groups tend to have lower experience levels which places them at a disadvantage in the labor market.

In the final two rows of Table 3, the share of jobs in an occupational grouping that can be done at home (Dingel and Neiman, 2020) and an index of exposure to health risks at work (Baker et al., 2020) are presented. Remote work possibility is associated with lower unemployment and exposure to health risks is associated with higher unemployment. Whites and Asians are concentrated in occupations with much higher proportions of jobs that can be performed remotely than blacks and especially Latinx. Racial differences in exposure to health risks are not large with blacks having an index that is 0.12 standard deviations above average.

4.1. Decompositions

We use a decomposition technique that allows us to estimate the separate contributions from these differences between groups in education, industry and other characteristics to racial gaps in unemployment rates. Specifically, we decompose inter-group differences in a dependent variable into the portions due to different observable characteristics across groups (the endowment effect) and to different “prices” of characteristics of groups. The Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition of the white-minority gap in the average value of the dependent variable, Y, can be expressed as:

| (4.1) |

We focus on estimating the first component of the decomposition that captures contributions from differences in observable characteristics or “endowments.” We use a popular alternative non-linear decomposition technique because the dependent variable is binary (Fairlie, 1999). See Couch et al. (2020) for more details.

Table 4 reports estimates from the non-linear decomposition procedure. Specification 1 reports estimates for factors contributing to the difference in unemployment rates between blacks and whites for April–June. The underlying measures of education, industry, occupation and other factors used in the decompositions are reported in Table 3. In April, when the gap of unemployment between whites and blacks was 3.8 percentage points, the decomposition reveals that having lower skills as measured by education contributes 0.56 percentage points to the unemployment gap. The largest factor contributing to the gap is the occupational distribution which adds 1.55 percentage points. Regional differences do not explain the gap, and potential work experience explains only a small part.

Table 4.

Decompositions - unemployment April, May and June 2020.

| Black - White | Latinx - White | Asian - White | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| April 2020 gap in unemployment rate | 3.8 | 5.4 | 0.9 | |

| Essential/major industry | Contribution | −0.29 | 0.05 | −0.37 |

| Std. Err. | (0.08) | (0.14) | (0.06) | |

| Major occupation | Contribution | 1.55 | 2.29 | 0.19 |

| Std. Err. | (0.12) | (0.19) | (0.07) | |

| Education level | Contribution | 0.56 | 1.00 | −0.72 |

| Std. Err. | (0.07) | (0.17) | (0.10) | |

| State | Contribution | −0.04 | 0.10 | 0.84 |

| Std. Err. | (0.11) | (0.20) | (0.18) | |

| Potential experience | Contribution | 0.13 | 0.14 | −0.01 |

| Std. Err. | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.03) | |

| Telework | Contribution | 0.19 | 0.32 | −0.04 |

| Std. Err. | (0.06) | (0.10) | (0.01) | |

| Health risk (Z-score) |

Contribution | −0.16 | 0.11 | 0.02 |

| Std. Err. | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | |

| May 2020 gap in unemployment rate | 6.0 | 6.9 | 3.6 | |

| Essential/major industry | Contribution | −0.13 | −0.14 | −0.22 |

| Std. Err. | (0.07) | (0.14) | (0.07) | |

| Major occupation | Contribution | 1.39 | 1.98 | −0.09 |

| Std. Err. | (0.12) | (0.18) | (0.07) | |

| Education level | Contribution | 0.65 | 1.05 | −0.85 |

| Std. Err. | (0.08) | (0.16) | (0.11) | |

| State | Contribution | 0.20 | 0.67 | 1.24 |

| Std. Err. | (0.12) | (0.19) | (0.20) | |

| Potential experience | Contribution | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.09 |

| Std. Err. | (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.03) | |

| Telework | Contribution | 0.12 | 0.17 | −0.03 |

| Std. Err. | (0.06) | (0.09) | (0.01) | |

| Health risk (Z-score) |

Contribution | −0.10 | 0.06 | −0.01 |

| Std. Err. | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.01) | |

| June 2020 gap in unemployment rate | 5.9 | 5.2 | 4.3 | |

| Essential/major industry | Contribution | 0.07 | 0.20 | −0.11 |

| Std. Err. | (0.08) | (0.13) | (0.08) | |

| Major occupation | Contribution | 1.04 | 1.26 | −0.05 |

| Std. Err. | (0.11) | (0.16) | (0.07) | |

| Education level | Contribution | 0.35 | 0.47 | −0.57 |

| Std. Err. | (0.08) | (0.14) | (0.11) | |

| State | Contribution | 0.12 | 0.73 | 1.56 |

| Std. Err. | (0.12) | (0.18) | (0.20) | |

| Potential experience | Contribution | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.07 |

| Std. Err. | (0.05) | (0.04) | (0.03) | |

| Telework | Contribution | 0.10 | 0.11 | −0.04 |

| Std. Err. | (0.07) | (0.08) | (0.02) | |

| Health risk (Z-score) | Contribution | −0.11 | 0.07 | 0.03 |

| Std. Err. | (0.02) | (0.03) | (0.02) | |

Notes: All nonlinear decomposition specifications use pooled coefficient estimates from the full sample of all races. Sampling weights are used in all specifications. Standard errors are reported in parentheses below contribution estimates. Sample size is 48,190 for April, 46,832 for May, and 45,334 for June.

Interestingly, the industry distribution of blacks does not contribute to why blacks have higher rates of unemployment in April 2020, but instead works in the opposite direction. Blacks actually have a “favorable” industry distribution meaning that overall they are more likely to be concentrated in industries that were hit less hard by COVID (e.g. Public Administration and Educational and Health Services). The magnitude of this contribution, however, is not very large working to narrow the gap in unemployment by 0.3 percentage points in April (i.e. if blacks were in the same industries as whites their unemployment rate would have increased by 0.3 percentage points). The signs and orders of magnitude of parameter estimates are generally similar for the months of May and June although the unemployment gap increases. Furthermore, estimates are robust to the inclusion or exclusion of the essential business dummy which is defined at the 4-digit industry level (results available by request).

The underrepresentation of blacks in jobs that could be done at home also placed them at higher risk of unemployment in the post-period but the contribution of this measure to explaining the overall gap is not very large (0.10 to 0.19 percentage points). Exposure to health risk works in the opposite direction.

For the Latinx-white decomposition, occupation and education mostly contributed to the increased gaps in unemployment. The less “favorable” occupational distribution among the Latinx labor force accounts for 2.3 of the 5.4 percentage point gap in April. Lower levels of education explain an additional percentage point. Their regional distribution and lower work experience also provide small contributions to the Latinx-white gap. Patterns of significance and order of magnitude largely stay consistent over the months of May and June. Underrepresentation in jobs that could be done at home by Latinx also contributed to relatively high unemployment rates (0.11 to 0.32 percentage points) whereas health risk did not explain much of the gaps.

The main explanatory factor for why Asians had higher post-COVID unemployment is because of an unfavorable state of residence distribution. Relatively high concentrations in the West which had higher unemployment and relatively low concentrations in the South which had lower unemployment underlies this finding. Asians were partly shielded from larger job losses, however, by a favorable industry distribution.

Unemployment in April 2020 includes a component related to longer-term structural unemployment that differs by race, and a new COVID related component. We attempt to separate these components in two ways. First, we estimate decompositions for the newly unemployed in April 2020 (i.e. those with an unemployment spell of less than or equal to 2 months). Second, we estimate a decomposition using February 2020 data to identify longer-term structural explanations that predate shelter-in-place restrictions.

Appendix Table A.1 reports estimates for the newly unemployed in April 2020. These decomposition results are similar to those in Table 4 which is consistent with the newly unemployed comprising the bulk of unemployment in April 2020. One difference, however, is that the black industry distribution appears to have protected blacks more when viewed as new unemployment in April 2020. Comparing the main results to February 2020 (Appendix Table A.2), the primary difference is that for blacks and Latinx occupational and educational differences contribute less to the gap in unemployment rates. This points to the unusual concentration of job loss due to state closures of businesses and reduced demand.

For completeness, we also estimate a decomposition using a partially expanded definition of unemployment that adds employed but absent job due to other reasons observations. Unfortunately, we cannot estimate decompositions using the full upper-bound definition because “NILF want job” observations do not have industry and occupation information. We find estimates that are roughly similar to those reported in Table 4 that are contained in Appendix Table A.3.

5. Conclusions

Social distancing restrictions mandated by state governments that closed down many businesses and more general reductions in consumer demand due to COVID-19 have driven an unprecedented increase in unemployment beginning with April of 2020. The impacts of COVID-19 on unemployment have been felt across the population but created a downturn dissimilar to any previous recession when viewed by race. Our analysis provides an initial look at the disproportionate negative impacts of COVID-19 using data from April 2020 and extending through May and June 2020. African-Americans experienced a sharp initial increase in unemployment in April 2020, but unlike in previous recessions, the 2:1 ratio of black relative to white unemployment rates did not hold. In fact, in April, the gap in black and white unemployment did not widen because unemployment increased by about the same amount across the two groups. Blacks were partly protected because of a favorable mix of the industries in which they are employed. An unfavorable distribution of employment across occupations, lower skills, less potential experience, and fewer opportunities to work remotely, however, each contributed to higher unemployment rates. In May and June, as whites were disproportionately rehired relative to blacks, the black-white unemployment gap widened to levels resembling those seen in the Great Recession. More than a decade of progress in reducing this gap was undone in the span of a few months.

Latinx were unequivocally hit disproportionately hard by COVID-19. Unemployment rates rose much faster for Latinx than for blacks or whites in April, the first month after the initiation of the shelter-in-place restrictions. The occupations, skill-levels and industries of the Latinx labor force placed them in an especially vulnerable position to the immediate layoffs that occurred as a result of the coronavirus. They also had the least opportunity to work remotely of any group, substantially lower than for whites. Although Latinx were rehired steadily in May and June, the pace was similar to the re-employment of whites which was not enough to lessen measured gaps in unemployment. In regression adjusted measures of unemployment gaps, Latinx consistently have larger estimated gaps in unemployment with whites than blacks do.

In response to stated concerns from the BLS regarding the possible misclassification of substantial numbers of those who were not at work and those who wanted a job but perhaps could not look due to the coronavirus, we tabulated an alternate unemployment series that we consider to be an upper-bound measure of unemployment. The upper-bound unemployment series raises the national unemployment rate to 24.4% in April, similar to the peak level observed during the Great Depression. This upper-bound measure also resulted in extremely alarming unemployment levels of 29.8% for African-Americans and 29.5% for Latinx, and raises concerns about official unemployment measures underestimating job losses among minorities. In June, these alternate unemployment rates remained at 23.2 and 20.8 percentage points for blacks and Latinx. For the nation, this alternate measure yields an unemployment rate of 17.4% in June.

These racial patterns in unemployment impacts from COVID-19 are important and will have major impacts on a wide range of short- and long-term economic outcomes. Minorities in general have less financial reserves and the unprecedented partial shutdown of the economy is likely to lead to immediate difficulty in meeting basic needs like nutrition and healthcare and a wave of late payments on basic bills including housing (Canilang et al., 2020). Additionally, minorities and Latinx in particular are less likely to qualify for unemployment insurance benefits. If the economy slips into a longer-term recession, additional waves of economic disruptions such as mortgage defaults, delinquent payments and bankruptcy filings are likely to follow. Perhaps, most importantly the ramifications of these unemployment spells will worsen longer-term trends in earnings, income and wealth inequality across racial groups. It is unclear whether government programs such as the $669 billion Paycheck Protection Program, the $300 billion in stimulus checks, and expanded unemployment insurance benefits will be able to stem these long-term impacts on racial inequality especially as cases continue to surge in July.

Footnotes

We thank Bill Sundstrom and participants at remote seminars at the Kauffman Foundation and GMU for comments and suggestions.

The average Latinx unemployment rate was 8.6% over the past four decades.

See Borjas and Cassidy (2020) for an analysis of impacts on immigrants. They find that immigrants, especially undocumented immigrants, were hit harder with job losses from the pandemic.

In results available on request we examine several alternative measures and find similar patterns.

We include a full set of interactions for March. The findings are robust to exclusion of the March 2020 data.

Appendix A.

Table A.1.

Decompositions - newly unemployed April 2020.

| Black - White |

Latinx - White |

Asian - White |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gap in newly unemployed rate | 2.8 | 4.8 | 0.7 | |

| Essential/major industry | Contribution | −0.38 | −0.11 | −0.36 |

| Std. Err. | (0.07) | (0.13) | (0.06) | |

| Major occupation | Contribution | 1.39 | 2.05 | 0.2 |

| Std. Err. | (0.11) | (0.18) | (0.06) | |

| Education level | Contribution | 0.52 | 0.85 | −0.71 |

| Std. Err. | (0.07) | (0.16) | (0.09) | |

| State | Contribution | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.72 |

| Std. Err. | (0.11) | (0.19) | (0.17) | |

| Potential experience | Contribution | 0.11 | 0.16 | −0.02 |

| Std. Err. | (0.03) | (0.04) | (0.02) | |

| Telework | Contribution | 0.17 | 0.29 | −0.04 |

| Std. Err. | (0.05) | (0.09) | (0.01) | |

| Health risk (Z-score) |

Contribution | −0.15 | 0.1 | 0.01 |

| Std. Err. | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | |

| Sample size | 47,353 | 47,353 | 47,353 | |

Notes: All nonlinear decomposition specifications use pooled coefficient estimates from the full sample of all races. Sampling weights are used in all specifications. Standard errors are reported in parentheses below contribution estimates. Newly unemployed is defined as unemployment with duration less than or equal to 2 months. Sample includes April 2020 labor force without individuals unemployed more than 2 months.

Table A.2.

Decompositions - unemployment February 2020.

| Black - White |

Latinx - White |

Asian - White |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| February 2020 gap in unemployment rate | 3.4 | 1.7 | −0.5 | |

| Essential/major industry | Contribution | −0.15 | 0.14 | 0.05 |

| Std. Err. | (0.07) | (0.08) | (0.03) | |

| Major occupation | Contribution | 0.33 | 0.72 | −0.11 |

| Std. Err. | (0.08) | (0.10) | (0.03) | |

| Education level | Contribution | 0.3 | 0.58 | −0.19 |

| Std. Err. | (0.05) | (0.08) | (0.05) | |

| State | Contribution | −0.08 | 0.07 | 0.13 |

| Std. Err. | (0.10) | (0.09) | (0.07) | |

| Potential experience | Contribution | 0.29 | 0.1 | 0.08 |

| Std. Err. | (0.05) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Telework | Contribution | 0.05 | 0.07 | −0.02 |

| Std. Err. | (0.04) | (0.05) | (0.01) | |

| Health risk (Z-score) |

Contribution | −0.06 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Std. Err. | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.01) | |

| Sample size | 58,982 | 58,982 | 58,982 | |

Notes: All nonlinear decomposition specifications use pooled coefficient estimates from the full sample of all races. Sampling weights are used in all specifications. Standard errors are reported in parentheses below contribution estimates.

Table A.3.

Decompositions – unemployment adding absent job (due to other reasons) April, May, and June 2020.

| Black - White | Latinx-White | Asian-White | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| April 2020 gap in unemployment rate | 5.1 | 6.7 | 3.5 | |

| Essential/Major industry | Contribution | −0.3 | 0.37 | −0.45 |

| Std. Err. | (0.09) | (0.14) | (0.08) | |

| Major occupation | Contribution | 1.84 | 2.59 | 0.21 |

| Std. Err. | (0.13) | (0.20) | (0.08) | |

| Education level | Contribution | 0.81 | 1.45 | −1.15 |

| Std. Err. | (0.08) | (0.19) | (0.12) | |

| State | Contribution | 0.13 | 0.38 | 1.16 |

| Std. Err. | (0.13) | (0.21) | (0.21) | |

| Potential experience | Contribution | −0.06 | −0.03 | −0.15 |

| Std. Err. | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.03) | |

| Telework | Contribution | 0.31 | 0.5 | −0.1 |

| Std. Err. | (0.07) | (0.12) | (0.02) | |

| Health risk (Z-score) |

Contribution | −0.25 | 0.16 | 0.05 |

| Std. Err. | (0.03) | (0.04) | (0.02) | |

| May 2020 gap in unemployment rate | 6.5 | 6.9 | 6.2 | |

| Essential/major industry | Contribution | −0.13 | −0.13 | −0.19 |

| Std. Err. | (0.08) | (0.14) | (0.09) | |

| Major occupation | Contribution | 1.49 | 1.97 | −0.03 |

| Std. Err. | (0.13) | (0.19) | (0.09) | |

| Education level | Contribution | 0.77 | 1.18 | −1.11 |

| Std. Err. | (0.09) | (0.18) | (0.12) | |

| State | Contribution | 0.38 | 0.74 | 1.50 |

| Std. Err. | (0.13) | (0.20) | (0.22) | |

| Potential experience | Contribution | 0.01 | 0.07 | −0.07 |

| Std. Err. | (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.03) | |

| Telework | Contribution | 0.19 | 0.27 | −0.05 |

| Std. Err. | (0.07) | (0.10) | (0.02) | |

| Health risk (Z-score) |

Contribution | −0.16 | 0.10 | 0.00 |

| Std. Err. | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.01) | |

| June 2020 gap in unemployment rate | 5.9 | 4.8 | 4.8 | |

| Essential/major industry | Contribution | 0.06 | 0.22 | −0.10 |

| Std. Err. | (0.08) | (0.12) | (0.09) | |

| Major occupation | Contribution | 0.99 | 1.10 | 0.13 |

| Std. Err. | (0.12) | (0.16) | (0.07) | |

| Education level | Contribution | 0.44 | 0.53 | −0.63 |

| Std. Err. | (0.08) | (0.16) | (0.11) | |

| State | Contribution | 0.23 | 0.84 | 1.77 |

| Std. Err. | (0.13) | (0.18) | (0.21) | |

| Potential experience | Contribution | 0.04 | 0.08 | −0.04 |

| Std. Err. | (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.03) | |

| Telework | Contribution | 0.14 | 0.16 | −0.05 |

| Std. Err. | (0.08) | (0.09) | (0.03) | |

| Health risk (Z-score) | Contribution | −0.15 | 0.12 | 0.07 |

| Std. Err. | (0.02) | (0.03) | (0.03) | |

Notes: All nonlinear decomposition specifications use pooled coefficient estimates from the full sample of all races. Sampling weights are used in all specifications. Standard errors are reported in parentheses below contribution estimates. Sample size is 48,190 for April, 46,832 for May, and 45,334 for June.

References

- Baker, Marissa G., Trevor K. Peckham, and Noah S. Selxas. 2020. “Estimating the burden of U.S. workers exposed to infection or disease: a key factor in containing risk of COVID-19 infection”. PLoS ONE 15(4): e0232452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bartik Alexander W., Bertrand Marianne, Ling Feng, Rothstein Jesse, Unrath Matthew. BPEA Conference Draft; Summer: 2020. Measuring the Labor Market at the Onset of the COVID-19 Crisis. [Google Scholar]

- Bick A., Blandin A. 2020. Real Time Labour Market Estimates During the 2020 Coronavirus Outbreak. VoxEU. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas, George J., and Hugh Cassidy. 2020. “The adverse effect of the covid-19 labor market shock on immigrant employment.” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. w27243.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. April 2020. “The Employment Situation – March 2020”. Department Of Labor, United States of America. USDL-20-0521.

- Cajner, Thomas, and Leland D. Crane, Ryan A. Decker, John Grigsby, Adrian Hamins-Puertolas,Erik Hurst, Christopher Kurz, and Ahu Yildirmaz. 2020. “The U.S. Labor Market during the Beginning of the Pandemic Recession” NBER WP 27159.

- Canilang Sara, Duchan Cassandra, Kreiss Kimberly, Larrimore Jeff, Merry Ellen, Troland Erin, Zabek Mike. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; 2020. Report on Economic Well-being of U.S. Households in 2019, Featuring Supplemental Data From April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Coibion O., Gorodnichenko Y., Weber M. 2020. Labor Markets During the Covid-19 Crisis: A Preliminary View. VoxEU. [Google Scholar]

- Couch Kenneth, Fairlie Robert. Last hired, first fired? Black-White unemployment and the business cycle. Demography. 2010;47(1):227–247. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couch Kenneth, Fairlie Robert, Huanan Xu. Racial difference in labor market transitions during the great recession. Res. Labor Econ. 2018;46:1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Couch, Kenneth, Robert Fairlie, and Huanan Xu. 2020. “The Impacts of COVID-19 on Minority Unemployment: First Evidence From April 2020 CPS Microdata,” Stanford University, SIEPR WP 20-021, May 20, 2020, and NBER WP 27246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dingel Jonathan I., Neiman Brent. How many jobs can be done at home? J. Public Econ. 2020;189:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairlie Robert. The absence of the African-American owned business: an analysis of the dynamics of self-employment. J. Labor Econ. 1999;17(1):80–108. [Google Scholar]

- Fairlie Robert, Sundstrom William. The racial unemployment gap in long-run perspective. Am. Econ. Rev. 1997;87(2):306–310. [Google Scholar]

- Fairlie Robert, Sundstrom William. The emergence, persistence, and recent widening of the racial unemployment gap. ILR Rev. 1999;52(2):252–270. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman R.B. Changes in the labor market for black Americans, 1948-72. Brook. Pap. Econ. Act. 1973;1973(1):67–120. [Google Scholar]

- Goolsbe Austan, Syverson Chad. Fear, Lockdown, and Diversion: Comparing Drivers of Pandemic Economic Decline 2020. NBER WP. 2020;27432 doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, Sumedha, Laura Montenovo, Thuy D. Nguyen, Felipe Lozano Rojas, Ian M. Schmutte, Kosali I. Simon, Bruce A. Weinberg, and Coady Wing. 2020. Effects of Social Distancing Policy on Labor Market Outcomes. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. w27280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hoynes Hilary, Miller Douglas, Schaller Jessamyn. Who suffers duringrecessions? J. Econ. Perspect. 2012;26(3):27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn Lisa B., Lange Fabian, Wiczer David G. Labor Demand in the Time of Covid-19: Evidence From Vacancy Postings and UI Claims. NBER WP. 2020;27061 doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montenovo Laura, Jiang Xuan, Rojas Felipe L., Schmutte Ian M., Simon Kosali I., Weinberg Bruce A., Wing Coady. Determinants of Disparities in Covid-19 Job Losses. NBER WP. 2020;27132 doi: 10.1215/00703370-9961471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orrenius Pia M., Zavodny Madeline. Mexican immigrant employment outcomes over the business cycle. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010;100(2):316–320. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau . 2020. Table 1. Experienced and Expected Loss of Employment Income by Select Characteristics. Small Business Pulse Survey. [Google Scholar]