Diversity drives excellence. Inclusion is central to the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and to our entire cardiovascular profession (1). We cannot achieve our mission to transform cardiovascular care and improve heart health without embracing the central tenets of diversity and inclusion (D&I). Diversity should encompass a range of qualities that are visible, such as race and sex, and invisible, such as geography, socioeconomic status, and opinion. Inclusion means valuing differences and finding common ground. Hallmarks of inclusion include feeling valued, trusted, authentic, and psychologically safe in expressing differing opinions and tackling tough issues without penalty (2).

D&I have been shown to be of significant benefit to individuals, organizations, and society (3). Indeed, optimal organizational performance requires D&I. An inclusive environment in the workplace is linked to employee engagement and retention. For example, organizations with gender diversity and stated human resources policies have less turnover; enhanced problem solving; and increased innovation, creativity, and perspectives. It is imperative that academic institutions foster D&I and equity with careful attention to pipeline barriers, retention, and leadership ascension of racial and ethnic minorities as well as women (4). It follows that diverse and inclusive organizations have been shown to have improved financial performance and thrive during economically challenging times. Our specialty and our College cannot reach its full potential until diversity is evident from our fellows-in-training members to our Board of Trustees.

Consequences of a Nondiverse Cardiovascular Workforce

In cardiovascular medicine, racial and sex disparities in care persist despite decades of studying the problem and proposing solutions. Not only do minorities experience worse outcomes once heart disease is established, the underutilization of high-tech procedures in minority populations is staggering. Recent studies show that 91% of patients in contemporary coronary stent trials were White (5). Although there is a suggestion that the worse outcomes in Black patients treated with coronary stents is due partially to social determinants of health, which may be outside of the cardiologist’s control (6), the fact that minority groups are less likely to be treated with effective cardiac medications and to be referred for cardiac rehabilitation at hospital discharge likely plays a role as well (7,8). Patient race appears to play a role in clinician decision-making (9).

In cardiovascular science and research, diversity among clinical scientists is crucial to ensuring that we ask the right questions, avoid ethical lapses in study design, and enhance trust with and engage with minority communities. New heart failure drugs have added powerful tools in the clinician’s armamentarium, but the trials upon which their U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval is based included just 5% Black patients (10,11). This robs the clinical community of crucial knowledge about benefits and risks in different populations and deprives Blacks and other minorities from the potential life-saving benefit of participating in clinical trials. A lack of cultural competency among principal investigators and study coordinators has been identified as a barrier to minority participation in research trials (12).

The mandate is clear: the ACC must take action to ensure a diverse specialty and that our profession and College benefit from contributions from all groups. How are we doing this?

The ACC Takes Action

D&I task force

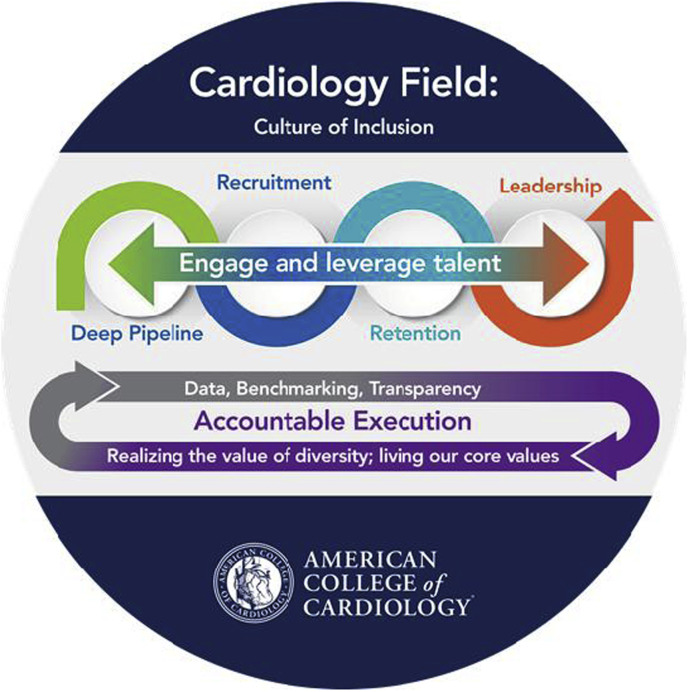

The ACC has recognized both diversity and health equity as being important for excellence and essential to the organization’s mission, and has created a Board of Trustees Task Force on each. The D&I Task Force (Figure 1 ) has achieved notable successes since its founding in 2017 (13). Nevertheless, the current crisis makes it clear that that we need to do more to acknowledge and counteract the structural racism in our profession and in our health care and academic institutions, including the ACC. As such, we are enlarging and intensifying our efforts to tackle overt and underlying factors that discriminate against or in any way disadvantage individuals or groups of cardiovascular professionals, teachers, learners, and investigators. Our past successes provide a strong foundation and momentum for continued change:

-

•

Enhanced organizational commitment and accountability, including creating ACC D&I principles and leadership competencies. The concepts and commitment have been embraced throughout the College, with more than two-thirds of the ACC's committees, sections, and chapters undertaking specific activities.

-

•

Creating a robust evidence base including a demographic profile of our profession (14) (with the Association of American Medical Colleges and American Board of Internal Medicine) and understanding medicine residents’ perceptions of cardiology and career choice (15). An analysis of the impact of race/ethnicity on professional life are underway as are listening sessions to better understand and respond to the experiences and needs of all ACC members.

-

•

A critical priority is diversifying our workforce and developing future leaders, including a deep pipeline of new cardiovascular professionals. Medical students can now elect complimentary membership, while the FIT Council has created a resident working group. The ACC leadership development programs for under-represented individuals range from the Young Scholars Program aimed at high school and college students to growing new leaders through our highly sought-after annual Clinical Trials Research boot camp programs.

-

•

Education is also essential. We are building on our existing suite of policy and position papers (including the first ever Workforce Health Policy Statements on Cardiologist Compensation and Opportunity Equity [16]), best practices descriptions, literature links, and perspective pieces and more on ACC.org. We are continuing to construct online modules and hold webinars on topics from disparities to microaggressions.

-

•

We are training ACC members to identify and overcome implicit racial and gender biases in their interactions with patients, trainees, and other professionals. Thus far, the Board of Trustees, the Nominating Committee, and a large segment of fellowship training program directors have received this education.

-

•

We are celebrating those making a difference through multiple communications and media and 2 new awards: the Distinguished Award for Leadership in Diversity and Inclusion (the inaugural winner was Richard Allen Williams, MD, FACC, founder of the Association of Black Cardiologists), and the Board of Governor’s Chapter Award for Diversity and Inclusion.

Figure 1.

The Work of the ACC D&I Task Force Is Structured Around Creating a Culture of Inclusion Within the Cardiology Profession

ACC = American College of Cardiology; D&I = diversity and inclusion.

Serving as a Resource to Diversify Training Programs

The ACC Cardiovascular Training Committee has actively engaged in the review of practices that can enhance diversity in training programs. This has included holding joint sessions with the D&I Task Force to discuss barriers to enhancing diversity and strategies to overcome those barriers. The College hosted the first symposium for program directors at Heart House, and hands-on training in implicit bias reduction and a discussion of strategies to enhance diversity in training programs were a major part of the daylong session. A stated goal of the joint effort is to develop resources to guide training programs as they respond to the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education’s mandate to attempt to recruit a diverse and inclusive workforce (17,18).

Conclusions

We are encouraged by our progress. The 2 newest JACC family editors-in-chief are women, and the proportions of women and minority speakers at ACC’s Annual Scientific Session have more than doubled. But, we must do more. We are working on eliminating structural racism in ACC committees, structures, and operations; educating members; and ensuring D&I competency and best practices in all areas.

The spring and summer months of 2020 in this nation have been marked by 2 pandemics: one a novel infectious disease (coronavirus disease-2019) and the other a centuries-old plague: racism. Blacks and Hispanics are over-represented in persons hospitalized and dying from the virus, are over-represented in those experiencing police brutality and violent acts of racism, and remain under-represented in the ranks of our profession. We reiterate the words in our June 2020 joint statement made with our sister heart organizations in which we condemned acts of racial violence and police brutality (19). Additionally, we support the Association of Black Cardiologists in the call to “participate with us in activities and approaches that seek to enhance the awareness of structural problems and to embark on specific corrective strategies” (20). This includes the provision of cardiovascular care, in social determinants of health and educational success, and in organized medicine. We will work with our partners and stakeholders to help dismantle structural racism and bias in the medical education pipeline that has contributed to the persistent lack of diversity in our specialty. We are committed to engaging all members of the cardiovascular care team and ensuring that ACC has earned the right to be seen as their professional home.

References

- 1.Douglas P., Williams K., Walsh M.N. Diversity matters. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1525–1529. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Travis D.J., Shaffer E., Thorpe-Moscon J. Getting real about inclusive leadership: why change starts with you. https://www.catalyst.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Getting-Real-About-Inclusive-Leadership-Report-2020update.pdf Available at:

- 3.Catalyst Why diversity and inclusion matter: quick take. https://www.catalyst.org/research/why-diversity-and-inclusion-matter/ Available at:

- 4.Albert M.A. #Me-who anatomy of scholastic, leadership, and social isolation of underrepresented minority women in academic medicine. Circulation. 2018;138:451–454. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Golomb M., Redfors B., Crowley A. Prognostic impact of race in patients undergoing PCI: analysis from 10 randomized coronary stent trials. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2020;13:1586–1595. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Batchelor W., Kandzari D.E., Davis S. Outcomes in women and minorities compared with white men 1 year after everolimus-eluting stent implantation: insights and results from the PLATINUM Diversity and PROMUS Element Plus post-approval study pooled analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:1303–1313. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.3802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tran H.V., Waring M.E., McManus D.D. Underuse of effective cardiac medications among women, middle-aged adults, and racial/ethnic minorities with coronary artery disease (from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005 to 2014) Am J Cardiol. 2017;120:1223–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li S., Fonarow G.C., Mukamal K. Sex and racial disparities in cardiac rehabilitation referral at hospital discharge and gaps in long-term mortality. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.008088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breathett K., Yee E., Pool N. Does race influence decision making for advanced heart failure therapies? J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMurray J.J., Packer M., Desai A.S. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:993–1004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McMurray J.J.V., Solomon S.D., Inzucchi S.E. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1995–2008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark L.T., Watkins L., Piña I.L. Increasing diversity in clinical trials: overcoming critical barriers [published correction appears in Curr Probl Cardiol 2020;55:100647] Curr Probl Cardiol. 2019;44:148–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American College of Cardiology ACC diversity and inclusion. https://www.acc.org/diversity Available at:

- 14.Mehta L.S., Fisher K., Rzeszut A.K. Current demographic status of cardiologists in the United States. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4:1029–1033. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.3247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Douglas P.S., Rzeszut A.K., Bairey Merz N. Career preferences and perceptions of cardiology among US internal medicine trainees: factors influencing cardiology career choice. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:682–691. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Douglas P.S., Biga C., Burns K.M. 2019 ACC health policy statement on cardiologist compensation and opportunity equity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:1947–1965. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ACGME Common Program Requirements (Residency) Sections I-V Table of Implementation Dates. 2019. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRResidencyImplementationTable.pdf Available at:

- 18.Crowley A.C., Damp J., Sulistio M. Perceptions on diversity in cardiology: a survey of cardiology fellowship training program directors. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020 Aug 25 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.017196. [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albert M.A., Harrington R.A., Poppas A. Letter from ABC and partners. https://www.acc.org//∼/media/Non-Clinical/Files-PDFs-Excel-MS-Word-etc/Latest%20in%20Cardiology/Articles/2020/06/Letter-from-ABC-and-Partners.pdf Available at:

- 20.Association of Black Cardiologists Inc. Structural racism and anti-Blackness in medicine are unacceptable and must be addressed. https://www.multibriefs.com/briefs/cb-abcnews/cb-abcnews080720.php Available at: