Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To provide a framework for a virtual curriculum during the COVID-19 pandemic for medical student educators that introduces and teaches clinical concepts important in urology and surgical specialties in general.

METHODS

We created a 1-week virtual urology course utilizing interactive lectures, case-based exercises, and faculty-proctored surgical video reviews. Students were assigned self-study modules and participated in case-based discussions and presentations on a topic of their choice. Students’ perceptions of urology as a specialty and the utility of the course was evaluated through pre- and postcourse surveys. Understanding of urologic content was evaluated with a multiple-choice exam.

RESULTS

A total of nine students were enrolled in the course. All students reported increased understanding of the common urologic diagnoses and of urology as a specialty by an average of 2.5 points on a 10-point Likert scale (Cohen's measure of effect size: 3.2). Additionally, 56% of students reported increased interest, 22% reported no change and 22% reported a decreased interest in pursuing urology as a specialty following the course. Students self-reported increased knowledge of a variety of urologic topics on a 10-point Likert scale. The average exam score on the multiple-choice exam improved from 50% before the course to 89% after the course.

CONCLUSIONS

Various teaching techniques can be employed through a virtual platform to introduce medical students to the specialty of urology and increase clinical knowledge surrounding common urologic conditions. As the longevity of the COVID-19 pandemic becomes increasingly apparent and virtual teaching is normalized, these techniques can have far-reaching utility within the traditional medical student surgical curriculum.

Key Words: Urology, Medical student education, Virtual education, COVID-19, Coronavirus

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic has a far-reaching and unprecedented impact on medical education. On March 17, 2020, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) released strong recommendations that medical students cease involvement in direct patient care activities.1 Medical schools across the country had to seek meaningful ways to teach clinical material virtually. Even as students start to return to clerkships, many institutions continue virtual didactic teaching, and have shortened clerkships to account for lost time. Delays or shortened clinical exposure may have disproportionate deleterious effects for specialties that are typically under-represented in the classroom-based medical school curriculum, including urology.2, 3, 4, 5 It is imperative to facilitate exposure to encourage medical student interest and to ensure that future physicians are proficient in recognizing and managing common urologic conditions.3 , 6

Adapting to the COVID-19 pandemic has required flexibility and novel techniques in urologic education of residents.7, 8, 9 There is emerging commentary regarding the importance of using virtual techniques to expose medical students to surgical specialties during the COVID-19 pandemic.5 , 10 , 11 However, discussions and suggestions thus far have not included urology.

Here, we outline our framework for a virtual course to teach medical students clinical urology. We employed a combination of interactive lectures, case-based discussions and surgical videos taught by attendings, residents and fourth year medical students. We also report our survey results regarding the impact of the course on the students’ perceptions and understanding of the field, level of interest in pursuing the specialty, and urologic knowledge.

METHODS

Our overall objectives in designing our curriculum were to: illustrate the breadth of practice within urology; discuss key topics in urology, with wide applications in medicine; and encourage self-guided discovery. We utilized the American Urological Association (AUA) medical student curriculum, Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology, the AUA Core Curriculum for residents, and Pocket Guide to Urology to create our content.12, 13, 14, 15 Lectures and case-based discussions were led by urology third- and fourth-year residents, faculty, and fourth year medical students, who previously completed general surgery and urology rotations, with their lectures supplemented by faculty and resident input. Videos of open, endoscopic, and robotic urologic procedures were proctored by faculty who pointed out the relevant anatomy and procedural steps.

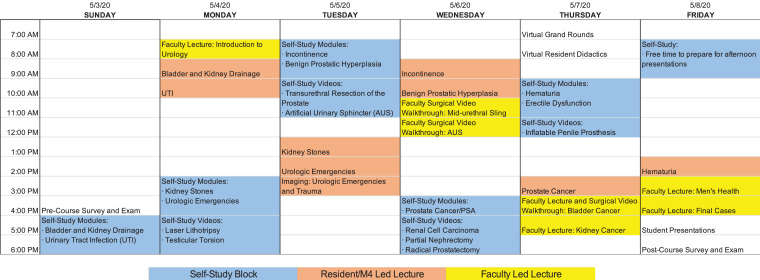

The course schedule, urologic topics covered, and self-directed study assignments can be found in Figure 1 . Students participated in department Grand Rounds and resident didactics. All didactics were held on Zoom. Grading for the course was pass-fail, based on class participation, faculty-proctored case-based evaluation and faculty-assessed 10 minute presentations on a topic of the student's choice.

Figure 1.

Week-long schedule for the virtual urology elective offered in May 2020. Students were directed to the following resources for self-study, related to the clinical topics being discussed: (1) AUA Medical Student Curriculum, (2) AUA Core Curriculum, (3) Surgical videos (provided as part of course materials).

We assessed students’ understanding and perceptions of the field through anonymous pre- and postcourse surveys, rated on a Likert-scale of 1 to 10, with Cohen's d measure of effect size. Students took an anonymous 18 question pre- and postcourse multiple choice exam to assess for improvement in clinical knowledge. Exam questions were created by urology residents or created by fourth-year medical students and edited by residents. Our study was reviewed and approved by Emory University's Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Nine students participated in the course. Eight students were third-year and 1 was a fourth-year medical student. Five students were male, 4 were female. Three had prior clinical experience in urology. Before the course, 1 student rated their understanding of urology as poor, 6 as fair, and 2 as good. After the course, 5 students rated their understanding of urology as good and 4 rated it very good. After the course, 2 students rated decreased interest in urology, 2 had no change, 4 had increased interest, and 1 had greatly increased interest. Changes in our students’ understanding of covered topics and perceptions of the field are depicted in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Pre and Postcourse Survey Questions and Averaged Responses Regarding Their (a) Understanding of Topics Covered in the Elective and (b) Perceptions of the Field

| Precourse | Postcourse | Cohen's D | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | |||

| I understand the diagnosis and treatment of UTI | 6.2 | 8.1 | 1.3 |

| I understand the difference between urge, stress, and mixed incontinence | 5.2 | 8.6 | 2.2 |

| I understand the pathophysiology, presentation, and treatment of benign prostate hyperplasia | 5.3 | 8.1 | 2.7 |

| I understand the workup, indications for surgery, and treatment principles of kidney stone disease | 4.0 | 8.6 | 3.0 |

| I understand the basic diagnostic workup of urologic emergencies | 2.0 | 7.9 | 4.4 |

| I understand the risk stratification and treatment options for prostate cancer | 2.0 | 7.0 | 3.2 |

| I understand the treatment options for kidney cancer | 2.3 | 7.8 | 3.8 |

| I understand the treatment options for bladder cancer | 2.4 | 7.2 | 2.7 |

| I am confident in my ability to workup hematuria | 4.4 | 8.3 | 2.5 |

| I have an understanding of a urologist's role in male sexual dysfunction | 4.7 | 8.8 | 3.9 |

| (b) | |||

| I have an understanding of what a urologist does and what pathologies they treat | 5.7 | 8.2 | 3.2 |

| I am considering urology as my specialty of choice | 6.8 | 6.2 | 0.3 |

| How difficulty do you perceive urology residency training to be? | 6.4 | 6.8 | 0.4 |

| What do you perceive a urologist's quality of life to be? | 7.6 | 8.0 | 0.3 |

| How achievable is it to be a urologist and have a family? | 8.6 | 7.9 | 0.6 |

All questions were answered on Likert scale ranging from 1-10. Cohen's d measure of effect size shown.

We asked the students for qualitative input on the course. Comments focused on two themes: faculty involvement and course organization or teaching methodology. Regarding faculty involvement, students reported, “All teachers were excited to teach,” “The faculty in urology at Emory are great! So just having them come in and talk to us was super educational and I think gave us a good sense of the breadth and depth you can achieve as a urologist,” and to “...have more attendings present lectures.” Comments surrounding course organization and teaching methodology included: “…the course was incredibly well organized... appropriate amount of information per day both during zoom and self-directed [study],” “AUA readings were helpful. Interactive lectures… [were] especially helpful” and a suggestion for “More surgical videos.”

Average student score was 50% (9/18) on the precourse exam and 89% (16/18) on the postcourse exam. Response rates were 100% (9/9) on the precourse exam and 89% (8/9) on the postcourse exam.

DISCUSSION

The COVID-19 pandemic will undoubtedly have lasting impacts on undergraduate medical education. There is an emerging focus on virtual strategies for medical education during and after the pandemic.16 Discussions regarding barriers and solutions for student exposure to surgical specialties have not yet included urology.5 , 10 , 11 Here we propose a framework for the virtual instruction of clinical urology to enhance interest and facilitate medical education.14 These resources and teaching methods are essential to accommodate social distancing practices that may continue for the foreseeable future. Furthermore, these techniques can also be incorporated into a regular third-year surgery clerkship as a tool to teach and expose students to urology.

The 1-week curriculum sought to introduce common urologic conditions and demonstrate the breath of urology, while on a virtual platform. It is important for all medical students to develop a strong urology knowledge base because primary care, internal medicine or emergency medicine physicians are often the first providers to see patients with a urologic complaint.3 Online learning modules have previously demonstrated improvement of urology-specific knowledge.17 , 18 Although a small sample size, medical students in our course demonstrated an increase in urologic knowledge and reported improved understanding of the field.

For our educational strategy, faculty, residents, and fourth year medical students taught material in accordance with their knowledge base over Zoom. Fourth year medical students provided a broad overview of medical topics within urology that was supplemented with resident and faculty input, corresponding lectures, and faculty-guided surgical videos. Residents contributed their clinical expertise through interactive case-based lectures, and attendings taught specialized or surgery-based topics. Based on feedback favoring interactive cases and surgical video-based learning methods, we encourage a focus on audience engagement and participation when planning lessons.

COVID-19 is projected to have lasting effects on medical education.16 At our institution, surgery clerkships have resumed but are shortened to account for lost time. Students now rotate on fewer subspecialties, and fewer will be exposed to urology. Though we are only 1 example, we predict other medical schools are facing similar challenges. Thus, we find it imperative to adapt virtual strategies to aid in medical student introduction to surgical specialties and maintain a well-rounded surgical education curriculum. This will be especially important for students who will not be exposed to urology, and for students who are undecided about their future specialty. To that end, the recorded lectures and resources from our course are currently being utilized to supplement the shortened surgery clerkship curriculum at our institution. We hope our approach can provide a framework of ideas for medical student educators to introduce medical students to surgical specialties such as urology using a virtual platform, both during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors have no financial or personal conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Lillian Xie, Andy Dong, Thien-Linh Le MD, James Jiang MD, Nourhan Ismaeel MD, Timothy Powers MD, Evan Mulloy MD, Jessica Hammett MD, Shreyas Joshi MD MPH and Kenneth Ogan MD for their contributions to the course.

References

- 1.Accountability CfP.Final report and recommendations submitted by the coalition for physician accountability's work group on learner transitions from medical schools to residency programs in 2020. AAMC. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2020-05/CPA_recommendations_learners_transitions_from_medical_schools_to_residencies_05122020.pdf. Published 2020. Accessed May 23, 2020.

- 2.Slaughenhoupt B, Ogunyemi O, Giannopoulos M, Sauder C, Leverson G. An update on the current status of medical student urology education in the United States. Urology. 2014;84:743–747. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casilla-Lennon M, Motamedinia P. Urology in undergraduate medical education. Curr Urol Rep. 2019;20:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s11934-019-0937-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zuckerman SL, Mistry AM, Hanif R. Neurosurgery elective for preclinical medical students: early exposure and changing attitudes. World Neurosurg. 2016;86:120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2015.08.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Go B, Rajasekaran K. Effect of COVID-19 in selecting otolaryngology as a specialty. Head Neck. 2020;42:1409–1410. doi: 10.1002/hed.26251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong D, Ganesan V, Kuprasertkul I, Khouri RK, Jr., Lemack GE. Reversing the decline in urology residency applications: an analysis of medical school factors critical to maintaining student interest. Urology. 2020;136:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2019.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vargo E, Ali M, Henry F. Cleveland clinic akron general urology residency program's COVID-19 experience. Urology. 2020;140:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwon YS, Tabakin AL, Patel HV. Adapting urology residency training in the COVID-19 era. Urology. 2020;141:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.04.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chick RC, Clifton GT, Peace KM. Using technology to maintain the education of residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Surg Educ. 2020;77:729–732. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abi-Rafeh J, Azzi AJ. Emerging role of online virtual teaching resources for medical student education in plastic surgery: COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2020;73:1575–1592. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2020.05.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dawoud RA, Philbrick B, McMahon JT. Letter to the editor regarding "Challenges of Neurosurgery Education During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic: A U.S. Perspective" and a virtual neurosurgery clerkship for medical students. World Neurosurg. 2020;138:545–547. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.04.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Medical students curriculum: core content American Urological Association. https://www.auanet.org/education/auauniversity/education-and-career-resources/for-medical-students. Updated January 2018. Accessed May 21, 2020.

- 13.Partin AW DR, Kavoussi LR, Peters C. Elsevier; Philadelphia, PA: 2021. Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology.https://www.elsevier.com/books/campbell-walsh-urology/partin/978-0-323-54642-3 [Google Scholar]

- 14.AUA Urology Core Curriculum | AUA University. American Urological Association. https://auau.auanet.org/core. Updated 2020. Accessed May 21, 2020.

- 15.JA W. J. Wieder Medical; Oakland, CA: 2014. Pocket Guide to Urology. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rose S. Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parker-Autry CY, Shen E, Nance A. Validation and testing of an e-learning module teaching core urinary incontinence objectives in a randomized controlled trial. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019;25:188–192. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Owen LE, Byrne DJ, Ker JS. A learning package for medical students in a busy urology department: design, implementation, and evaluation. Urology. 2008;72:982–986. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]