Abstract

Fikih Kebencanaan (Coping with Disaster) is a product of Muhammadiyah's ijtihad to respond to contemporary problems, especially geological and non-geological disasters, which later become the normative foundation for the mitigation of health disasters such as the Covid-19 pandemic. The paradigm of the present research is a transdisciplinary qualitative type with a phenomenological approach. The research analyzed the reasoning of Fikih Kebencanaan and its actualization in Covid-19 mitigation, the medical health movement and the reconstruction of fiqh of worship during an emergency in particular, and how to deal with the disaster theologically in general. The results showed that the reasoning of Fikih Kebencanaan was expanded in terms of medical, theological, and educational movements. Medical movement is a health movement in the form of providing 74 Covid-19 Standby Hospitals capable of accommodating 3917 patients or 36.15% of the total number of cases in Indonesia, followed by the distribution of masks, gloves, and foods to 401,209 Covid-19 affected victims. The theological movement was in the form of religious provision in which Muhammadiyah attempted to reconstruct classical Islamic jurisprudence of the rule of worship to adapt to an emergency. In contrast, the Indonesian Council of Ulema (MUI) applied zoning. The educative movement was a preventive effort to counter narration stemming from micro-celebrity Da'i (Islamic preacher) & Influencers (religious preachers) tried to circumvent religious provisions with their viral statements on social media. This effort was realized by developing neuroscience Islamic education with learning media in visualization that combined modern comics and contemporary cartoons with cinematic narratives. The neuroscience Islamic education movement tried not to use the dogmatic-monolithic approach as in classical education.

Keywords: Muhammadiyah, Fiqh of disaster, Covid-19, Islamic education, Neuroscience

1. Introduction

The spread of covid-19 has become a public health crisis which first exploded in December 2019 in Wuhan, China. It quickly spreads to more than 213 countries infecting 2.402.350 people. The number of death recorded is 163.097 or 6.78% of the total infected cases [1]. Considering the severity that the virus causes, WHO declared the current crisis as global pandemic [2] which is way more dangerous than other previous crisis such as SARS, MERS [3] and H1N1 or swine flue [4]. The USA has accused China as the one who develops Covid-19 as a biological weapon. However, Hao has denied this accusation saying that there are no traces of the virus in Wuhan laboratory [5]

Indonesia is among the countries in South East Asia which is severely affected by this pandemic with a total case of 10.834. It also records 831 deaths as of May, 2nd 2020 [[6], [7]]. It makes Indonesia the country with the highest fatality rate in the world. Other countries such as the USA, Italia and Australia only record relatively lower death rate at around 6.78% [8]. As a country with Muslim majority, Indonesia is prone to become a new epicenter because of Muslim praying culture which always involves close contact. Therefore, this article argues that it is important to reconstruct fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence) in the case of covid-19 public health crisis. It is also because the social distancing policy doesn't seem to be effective in stopping infection rate [9] Furthermore, an emergency provision issued by Indonesian council of Ulema has not given serious impact in preventing the spread [10].

The main cause of Indonesia's high fatality rate is the lack of health facilities, starting from the scarcity of masks, expensive hand sanitizers to the lack of Covid-19 Alert Hospitals [11,12]. Besides, there are also social factors such as the anti-science attitude of religious leaders, especially micro-celebrities [13]. They try to circumvent the Ulama's fatwa because of their arrogant attitude in religion and feel immune to Corona just because they pray a lot. This condition is still exacerbated by the emergence of influencers [14] who spread anti-intellectualism on social media by saying that Covid-19 is just a conspiracy of the global elite [[15], [16]]. Therefore, research is needed on the mitigation of the Covid-19 health disaster from an Islamic perspective that can counteract anti-science and anti-intellectualism. In this regard, the role of Muhammadiyah as one of the oldest and largest socio-religious organizations in Indonesia is interesting to observe. Muhammadiyah has compiled Disaster Fiqh which later became a normative foundation in the Covid-19 mitigation [[17], [18]].

This study aims to analyze the mitigation of Covid-19 based on Disaster Fiqh from the perspective of the Muhammadiyah Ulama. Muhammadiyah responded to Covid-19 with a different movement from other socio-religious organizations in the way it tries to counter the anti-scientific attitudes and anti-intellectualism of Da'i micro-celebrities and other influencers. Muhammadiyah responded to Covid-19 in three fields, namely medical, theological and educational aspect [[17], [18]]. In the medical field, Muhammadiyah provides health facilities in the form of 74 Covid-19 standby hospitals complete with medical personnel and humanitarian volunteers. In the theological field, Muhammadiyah has compiled worship guidance in the midst of Covid-19 so that houses of worship do not become clusters of Covid-19 spread. In the field of education or education, Muhammadiyah develops Islamic education materials for many people to cope with the situation.

These three different efforts to respond to Covid-19 are different from other socio-religious organizations which generally deal with Covid-19 in only two fields, namely theological and sociological aspect such as preaching [19]. For instance, such preaching was done by Evangelical Christian church in the USA [20], The Vatican in Italy [21], some Modern Orthodox Jewish communities in America [[22], [23]] and the Diyanet in Turkey [24]. Besides, several socio-religious organizations tend to respond negatively to Covid-19 and one of which is coming from religious groups in Taiwan, Bangladesh [21], Korea, West Indies [25] and faith community organizations of other religions [26]. Moreover, the Tablighi Jamaat which is scattered in various countries responded to Covid-19 with an anti-science and anti-intellectualism attitude and ignored all calls for physical distancing [27]. The same thing happens to all religions in Japan that reject physical distancing and are brave enough to face enormous risks [28].

So far, research on Disaster Jurisprudence is still limited to natural or geological disasters such as earthquakes, tsunamis, eruptions, and hurricanes, as is the trend of disaster research in Australia [29], India [30], and Asia [31], including disasters in the perspective of religion in Indonesia [32]. Several studies have begun to investigate non-natural or non-geological disasters such as social crises and inter-ethnic conflicts such as the Rohingya humanitarian disaster in 2017 [33,34]. Research on the disaster with a religious approach was conducted by El-Ied, which studied crisis management in Islam conceptually [35]. Research around jurisprudence which is especially related to the mitigation of the Covid-19 pandemic, however, (a non-geological health disaster) has never been done. Several studies about Covid-19 itself has been carried out recently [36,37] but they mainly focus on vaccination, treatment, healing and immunity. There are almost no studies conducted from a social and religious perspective as in the present study.

Thus, there is a gap that has not been touched by many previous researchers. This gap concerns the socio-religious and education impact that Covid-19 has created. Therefore, research on Disaster Jurisprudence which focuses on the mitigation of Covid-19 from the perspective of the neuroscience of Islamic education is expected to fill out this gap. The findings of this study will have implications for the new discourse in the study of non-geological health disaster mitigation that goes beyond traditional fiqh reasoning. The concept of Covid-19 mitigation in this study can be a model or prototype for mitigating health or non-geological disasters that are very likely to occur repeatedly in the future, both by the government and civil society including religious and social organizations such as Muhammadiyah. Specifically, for the case of Covid-19, WHO has predicted that this pandemic will appear periodically. For example, although Wuhan has declared Covid-free for two months (March 25, 2020), the city has to be Locked down the second time (April 8, 2020) because there are many cases of re-infection. Therefore, the findings of this study can be a prototype of non-geological health disaster mitigation such as Covid-19 and the like.

2. Literature review

2.1. Disaster management in Islam

Disaster management in Islam can at least be explored from stories written in the Koran and Hadith. First, the flood disaster during the time of the prophet Noah which lasted for 40 days and 40 nights and killed all living things except those on board the ship of Noah (QS. Ash-Syu'ara verse: 117–119 & QS Hud [ 11]: 25–26). Second, the catastrophic rain of stones at the time of Prophet Lut as in the city of Sodom (now known as the border of Israel Jordan) (QS. Hud [11: 82). This disaster occurred as a punishment from Allah because the people of the prophet Luth had same-sex sexual orientation or what is now known as LGBT. Third, the famine which lasts fro 7 consecutive years which is narrated in Surah Yūsuf verses 47–49. Fourth, health disasters in the form of outbreaks of infectious diseases (Tha'un) that occurred in the land of Shams in the years 638-639 AD (17-18 H). This disaster killed more than 30% of the population of Shams including the Governor and the Companions of the Prophet (Muadz bin Jabal and Suhail bin Amr) whose piety was beyond doubt.

Of the four disasters in Islam, only Tha'un disasters are relevant to Covid-19, because both of them are health disasters. The “Tha'un” and Covid-19 pandemic has many things in common. Rasullah Muhammad Saw said, “If you hear the plague raging in a country, then don't enter it; and if you are in that area do not go out to run from it ”(Narrated by Bukhari & Muslim). This hadith is very relevant to the mitigation of Covid-19, such as lockdowns, self-quarantine, self-isolation, staying at home, maintaining distance, and so on [38].

The Koran and Hadith have the concept of disasters that are rich in meaning, such as Muṣībah (events that befell humans) [39], Balā ' (good or bad tests or trials) [40], Fitnah (misery due to social events) [41], 'Ażāb (torment) [40], Fasād (ugly, bad and dispute) [42]; Halāk (death, perishing, and annihilation) [40], Tadmīr (destruction) [43], Tamzīq (destruction for mankind) [17], ‘Iqāb (reprisal or punishment) (repeated 80 times) [39], Nāzilah (bringing down punishment) [39]. On the one hand, disaster can cause serious disruption to human life, (muṣībah) [44], and it also results in a loss, damage, destruction (tadmīr and tamzīq), or the paralysis of social functions of society (halāk and fasād) [[40], [43]], as well as conflict and chaos (fitnah) [41]45. Disasters not only befall those who are guilty or sinful, but also those who are good and righteous and have faith. If a sinful human is hit by a disaster, then it can be seen as iqāb, nāzilah, or even ażāb [39], for his actions. Whereas for good and true people affected by the disaster, it means balā' or tests to improve the quality of their faith [40]. As for those who died as a result of a disaster but were innocent, they died as a martyr (glorious in the sight of God).

Disaster management in Islam is very much determined by the perspective to interpret disaster. In the Koran surah Al-Baqarah (2): 155, it is stated that a disaster is a form of love from Allah SWT and a medium of introspection. Therefore, disasters must be treated as a test, which opens up opportunities for people to improve the quality of their faith and devotion. Thus, disasters in Islam must be overcome with the spirit of a better life, not fatalistic and pessimistic. In Tarjih's perspective, disaster management is carried out in three stages, namely preventive measures, emergency measures, and recovery [18].

First, preventive measures, namely analyzing the causes of disasters and understanding the role of humans as caliphs (representatives of God) on earth. This step was inspired by the story of the Prophet Yusuf in the Koran surah Yūsuf verses 47–49. God commanded the people of Prophet Yusuf to do farmings fro seven years in a row and the harvest should be stored except for a little to be consumed because there will be a famine which will last for 7 years. Second, disaster emergency response, which is a series of activities carried out immediately at the time of a disaster to deal with the adverse effects, which include activities to rescue and evacuate victims, property, the fulfilment of basic needs, protection of vulnerable groups, management of refugees, and emergency recovery. This step is inspired by the Qur'an surah al-Māidah (5): 32 which states that whoever takes care of the life of a human being, it is as if saving the lives of all humans. Third, recovery is the rehabilitation of public services and the reconstruction of post-disaster infrastructure. This step is extracted from the Koran surah Ar-Ra'du which states that God does not change the fate of people until they change their own destiny [Q.S. al-Ra'du (13): 11].

2.2. The mitigation of Covid-19 from Islamic jurisprudence perspective

Fikih Kebencanaan (Coping with Disaster) is a product of ijtihad of the Muhammadiyah's Council of Religious Affairs (Majelis Tarjih dan Tajdid Muhammadiyah) which was formalized through the Tarjih National Deliberation Decree on Fikih Kebencanaan (Coping with Disaster) in Decree number 102/KEP/I.0/B/2015 dated 29 Syakban 1436 H/16 June 2015 M [46]. In the perspective of Fikih Kebencanaan (Coping with Disaster), Covid-19 is a health disaster. It is on this basis that in mitigating Covid-19 Muhammadiyah prioritizes the provision of health facilities, especially hospitals. This reasoning for Fikih Kebencanaan (Coping with Disaster) is interesting to investigate because it offers a different concept from other fiqh reasoning which is only in the form of religious recommendation. Most often, it is only limited to a narrow and black-and-white perspective, so that it is considered by some as the cause of ignorance and setback. It was at this point that Muhammadiyah, based on Islamic tradition, then reinterpreted and reconstructed the fiqh reasoning with a new nuance [47,48].

The classical Islamic jurisprudence that has been developed only focuses on the level of concrete legal norms (al-aḥkām al-far'iyyah). Muhammadiyah's fiqh reasoning is built on three-tiered norms, namely basic values (al-qiyām al-asāsiyyah), general principles (al-uṣūl al-kulliyyah), and concrete legal norms (al-aḥkām al-far'iyyah). These three tiered norms are very relevant to Ibn Sina's multilevel hierarchical sense which forms the philosophical foundation of Islamic education neuroscience, namely material sense (al-'Uqul al-Hayyulaniyyah), potential sense or capacity (al-'Uqul bi al-Malakah), actual reasoning (al-'Uqul bi al al-fi'l), and acquisition (Al-'Uqul al-Mustafad) [49,50]. Hierarchy of reasoning or taxonomy of thinking built in Fikih Kebencanaan (Coping with Disaster) makes it able to continue to adapt to the times and can address a variety of contemporary problems [47,48] one of which is the new reasoning for Fikih Kebencanaan (Coping with Disaster).

Fikih Kebencanaan (Coping with Disaster) in Muhammadiyah's perspective offers religious guidance both on how Muslims in particular, and people in general, respond to disasters, theologically. It also includes preventive efforts to post-disaster technical handling [46]. Covid-19 faced by humankind lately can be categorized as a disaster, and therefore the reasoning of Fikih Kebencanaan (Coping with Disaster) of Muhammadiyah's perspective can be a lens to see to what extent Muhammadiyah has done its efforts in overcoming this pandemic.

In the perspective of Fikih Kebencanaan (Coping with Disaster), Covid-19 is not merely a health disaster. It can be seen as a form of God's love and affection for humans [46]. People who hold his belief will see that everything that God has given is “good”. This perspective is based on theological arguments in several religious texts, such as QS al-An'am (6): 54, QS an-Naḥl (16): 30, QS Ali ‘Imrān (3): 18; al-A'rāf (7): 29; asy-Syūrā (42): 17, and QS an-Naḥl (16): 29 [46]. This attitude is very relevant to the findings of research in the field of neuroscience, especially about positive thinking and positive feeling, where humans must always have positive thinking to their Lord, so that they always behave positively in a crisis [45]. In psychology, people who are always able to be positive in the middle of a crisis will have resilience or endurance [51] and the ability to adapt to a pandemic, so that they remain productive in difficult situations.

3. Research method

3.1. Research approach

The present study adopts interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary paradigm as recommended by Abdulah [52] who links the theological, sociological and medical-scientific dimensions [53]. The Covid-19 pandemic is not merely viewed from a medical perspective as most studies have done, but this research wants to examine the sociological impact this pandemic has created and the theological adaptation required to deal with it. Methodologically, this study uses a qualitative approach of phenomenology [54]. The qualitative approach was chosen because this study aims to reach out the meaning and the role that religion plays in Covid-19 mitigation both medically, sociologically, and theologically [55].

3.2. Research settings

The research setting is Yogyakarta Indonesia as the headquarter and the birthplace of the Muhammadiyah organization. Another reason for choosing Yogyakarta as the research setting was due to the small rate of spread of Covid-19. In August 2020, Yogyakarta was in the second-lowest rank as the province with the lowest cases of Covid-19 infection. Other big cities in Indonesia such as Jakarta and Surabaya have a high level of Covid-19 spread. Thus, Yogyakarta becomes the control center for Covid-19 through the Muhammadiyah Command Covid Center (MCCC).

3.3. Research participants

The research participants consisted of two segments, namely the expert segment and the Muhammadiyah community segment. The expert segment is a team of Fatwa and Guidance Development Division (Divisi Fatwa dan Pengembangan Tuntunan). It is one of seven divisions within Muhammadiyah’s Council of Religious Affairs (Majelis Tarjih dan Tajdid Muhammadiyah). Even though the fatwa was originally formulated by this division, when it has been stipulated, it will become the official stance of Muhammadiyah’s Council of Religious Affairs. The fatwa could, even to a certain extent, become the official stance of the Muhammadiyah as an organization in general, for instance, this disaster fiqh. In cases where expert analysis from other fields of science are needed, the Fatwa And Guidance Development Division will ask members of Muhammadiyah’s Council of Religious Affairs from different division or other people outside the council to help formulate the fatwa to be issued. In other words, every item in the formulation of disaster fiqh is an accumulation of decisions with all members with various scientific points of view. This council, generally, consists of 56 scholars or scientists with diverse scientific expertise, such as Islamic studies, health, medicine, psychology, sociology, culture, and education.

The participants from the community segment consist of 100 (one hundred) informants. These informants were selected based on the recommendations of the heads of the regional, branch, regional and branch leaders. The criteria for selecting the informants were based on the active participation of the informants in campaigning against Covid-19 such glorifying the jargons such as “stay at home, work from home, physical distancing, social distancing, wear masks, wash hands, use hand sanitizers” and so on.

3.4. Data collection

Considering that this research was conducted in the middle of physical distancing, all research activities, especially data collection, both interviews, observation and documentation, were carried out online. Interviews with expert segment informants focused on the reasoning of jurisprudence for disasters that understands Covid-19 as a health disaster. This expansion of fiqh reasoning has led to a policy of providing 74 COVID-19 standby hospitals. The documentation and observation data are taken from graphic info on the official MCCC website. This web site is considered representative to display the research data needed.

The collection of data from the Muhammadiyah community segment was carried out by distributing questionnaires online. This questionnaire contains 18 questions according to the number of changes in body guidance in the Covid-19 emergency. The change in the prayer guide is intended as a coping guide for Covid-19 for Muhammadiyah members. Therefore, the dissemination of lift is intended to gather information related to the compliance or obedience of informants to the fatwas of the Muhammadiyah ulama. The higher the obedience of Muhammadiyah members to ulama fatwas, the smaller the spread of Covid-19 in Indonesia can be.

3.5. Data analysis

Data analysis is carried out in four steps: data display, data reduction, and data meaning. The validity of the data is done by triangulation, which confirms one data with another so that the data's validity and reliability are obtained. Operationally, data analysis is carried out by coding descriptive, interpretative, and meaningful creativity data. Data coding is done by giving creative meaning to the findings of research results which can be organized into three important themes: 1) Muhammadiyah's response to Covid-19 in the health or medical field, is focused on providing 74 Covid-19 standby hospitals; 2) Muhammadiyah's response to Covid-19 in the field of theology is focused on religious guidance in the midst of the Covid-19 emergency; 3) Muhammadiyah's response to Covid-19 in the field of Islamic education is focused on educating the wider community to prevent Covid-19 with a neuroscience approach.

4. Findings and discussions

4.1. Muhammadiyah and the effort to mitigate Covid-19

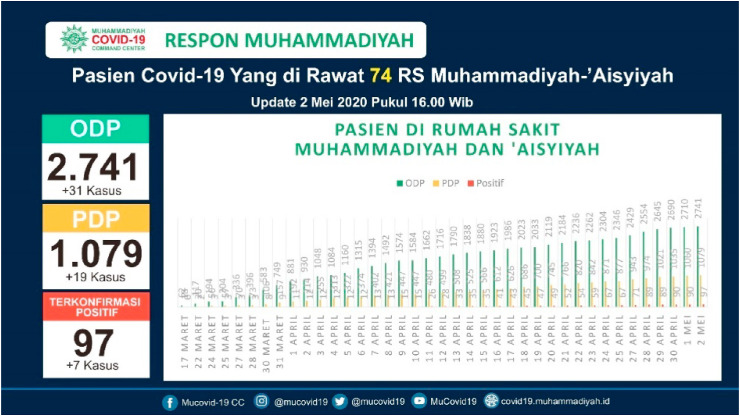

In the perspective of Islamic Jurisprudence as interpreted by Muhammadiyah leading clerics, Covid-19 is a health problem and is categorized as a non-geological disaster. Therefore, it is important to provide health facilities. This is supported by the Muhammadiyah’s Council of Religious Affairs (Majelis Tarjih dan Tajdid Muhammadiyah) provision which obliges anyone who is tested positive for Covid-19 to seek medical assistance as a form of endeavour [56]. On this basis, Muhammadiyah took concrete action by preparing 74 hospitals complete with medical personnel, logistical assistance, religious and psychological consulting services, and disinfectants. This is what distinguishes Muhammadiyah's line of reasoning from the others. There are guidelines which act ethically-normatively. At the same time, there are social-medical efforts and concrete actions. Fig. 1 shows the patient who is tested positive for Covid-19 and was taken care of at 74 Muhammadiyah Hospital [57].

Gambar 1.

The total of Covid-19 patients in 74 Muhammadiyah-‘Aisyiyah hospitals.

Fig. 1 Above shows that 74 Muhammadiyah Hospitals have provided treatment for 2741 people under supervision (ODP), 1079 patients under supervision (PDP) and 97 positively tested patients. This data shows that Muhammadiyah Hospital has helped to ease the state burden by 36.15% of the total number of Covid-19 cases in Indonesia (10,843).

Muhammadiyah's response to the Covid-19 pandemic included four things as follows. First, it has online religious consultation services during the Covid-19 pandemic. As of May 2, 2020, this service has received more than 40 inquiries related to religious practices.1 Wisdom-based online Jurisprudence is carried out collaboratively by professionals. It is one of the characteristics of 21st-century thinking skills [58] as it does not provide provisions that are dogmatic-monologic. Rather, this service prioritizes dialectic and interactive approach. Secondly, Muhammadiyah also opens psychological consulting services. On May 2, 2020, there were 69 people invited. They are not only Indonesian citizens, but also foreign citizens [57]. This shows that there is a wisdom in Islamic Jurisprudence which supports “out of the box” thinking, one of the ways in which the brain works [59,60]. It is interpreted as crossing the boundaries of religion, ethnicity, race, and nation. Thirdly, Muhammadiyah actively involves in the distribution of masks, food, hand sanitizer, and other important needs to fight Covid-19. The total number of distributed package has surpassed thousands of packages [57]. This shows that Islamic Jurisprudence also resembles Maslow's basic needs hierarchy theory [61,62], and the mitigation is informed by theoretical references. Lastly, there is a donation scheme through Lazizmu. The total donation as of 30 April 2020 has reached Rp. 11,234,805,193 [57]. The total donation above has been issued in the form of aid packages and is published periodically and transparently in this website: https://covid19.muhammadiyah.id/.

4.2. The perspective of Muhammadiyah about prayer guidance during emergency situation (the case of Covid-19)

The extended fiqh concept as explained previously does not necessarily neglect certain specific fiqh concept such as fiqh of worship. One of the fiqh product in this specific concept is guidance for prayer in an emergency situation. It is stipulated in Muhammadiyah central board circular letter number 02/EDR/I.0/E/2020 of 29 Rajab 1441 H/24 March 2020. The full guidance is available in Table 1 . Eighteen religious fatwas on guidance for worship in the Covid-19 emergency situation in Table 1 were seen by more than 300 Muslims and were circulating on social media during the pandemic. This religious fatwa is Muhammadiyah's response to prevent the transmission of Covid-19 in places of worship (mosque) or religious rituals. This is because in Islam there are many religious rituals which involve a crowd of people who usually require a handshake and other physical contact, such as the five daily prayers, the tabligh akbar (mass religious meeting), Friday prayers, and corpse prayers. Religious provisions in Table 1 regulate changes in the way of worship during emergency situations. Some significant changes to the procedure for worship are: 1) replacing the prayer call, "ḥayya‘ alaṣ-ṣalah“ with” ṣallū fī riḥālikum “or other relevant ones; 2) congregational prayers in the mosque are converted into individual prayers at home; 3) Friday prayers in the mosque are replaced by zhuhur prayers at home; 4) corpse prayer is replaced by gaib prayer; 5) tarawih prayers in the month of Ramadhan 1441 H/2020 M may not be held in the mosque but at homes, and many more changes to the procedures for worship in the emergency conditions of Covid-19. Therefore, this religious fatwa of the Muhammadiyah Ulama should have implications for the closure of many Indonesian mosques.

Table 1.

Prayer guidance in an emergency situation.

| No. | Provisions | Response |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Muslim attitudes in facing COVID-19 | Page Views 337 |

| 2. | Reward of martyrdom for those who died due to covid-19 | Page Views 454 |

| 3. | Treatment efforts undertaken by experts and the government in providing health care | Page Views 347 |

| 4. | Efforts to prevent the spread of the covid-19 outbreak are jihad, any actions that carry the risk of transmission are wrong | Page Views 143 |

| 5. | Must abide by the instructions/protocol on social (physical) distancing and stay at home (work from home) | Views 260 |

| 6. | Prayers remain mandatory during the emergency situation | Page Views 323 |

| 7. | Congregational prayers at the mosque during the covid-19 emergency | Page Views 234 |

| 8. | The call to prayer during covid-19 emergency | Page Views 215 |

| 9. | Prayers for people who (because of their profession) are required to be outside the home | Page Views 84 |

| 10. | Rukhsah prayer for covid-19 medical service personel | Page Views 235 |

| 11. | Friday prayers during covid-19 emergency | Page Views 290 |

| 12. | Worship in Ramadan and Shawwal during covid-19 Emergency | Page Views 274 |

| 13. | The treatment of the corpses of covid-19 victim | Page Views 171 |

| 14. | Corpse prayers for covid-19 victims and takziyah activities | Page Views 273 |

| 15. | Marriage and walimah/reception at the time of covid-19 emergency | Page Views 290 |

| 16. | Increase zakat, donation and alms during covid-19 emergency | Page Views 121 |

| 17. | Doing a lot of good things and helping each other during covid-19 emergency | Page Views 159 |

| 18. | Istighfar, repentance, prayer to Allah, the Koran recital, dhikr, prayer for the prophet and kunut nadzilah in covid-19 emergency | Page Views 376 |

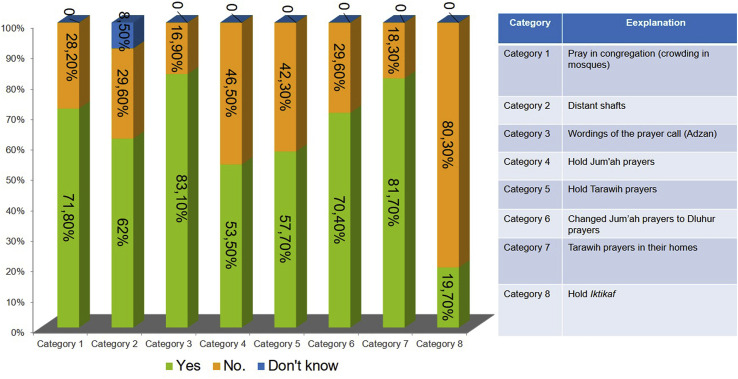

The question is, do Muslims fully follow these religious provisions? The answer is no! Fig. 2 shows that 71.80% of Muslims still pray in congregation (crowding in mosques), 62% of five daily prayers are still conducted but with distant shafts, 83% replace wordings of the prayer call: ḥayya ‘alaṣ-ṣalah “with” ṣallū fī riḥālikum ”, 53.50% of mosques in Indonesia are still open, so they still hold Friday prayers. But 70.40% of Muslims have changed Friday prayers to Dluhur prayers. 81.70% also perform tarawih prayers in their homes, and only 19.70% do it in the mosque.

Fig. 2.

Muslims' obedience to religious provision in the emergency conditions of Covid-19.

Fig. 2 above shows that Muslims in Indonesia in general and especially in Yogyakarta have not fully obeyed religious fatwas, especially that of Muhammadiyah's. In fact, the provisions of the Muhammadiyah cleric is legal and convincing. They are not contrary to the other religious authority institutions. More than that, some religious provisions are seen as “theological disasters” because they are considered to disobey the commands of Allah and His Messenger because they dare to change the way of worship. In this regard, the the head of The Muhammadiyah Tarjih Center (Pusat Tarjih Muhammadiyah)2 stated:

Some people do not heed religious provisons, especially tarjih's provision. It is because of three reasons. First, regional Muhammadiyah leaders, as in certain branches consider their area to be safe, and not yet affected by covid-19. So according to them these provisions only applied to those in the red zone (most impacted by covid-19). They arent aware of the fact that these provision applies to all members of Muhammadiyah in all its branches. Second, Muslims who do not obey these provisions may not be Muhammadiyah members, even though the mosque where they pray is under Muhammadiyah's authority. Third, a number of local clerics in the villages, including those who were viral on social media, deliberately rejected the provisions from official state institutions, issued by both the Indonesian Council of Ulama (MUI/Majelis Ulama Indonesia) and the Religious Social Organization such as Muhammadiyah.3

The statement of the head of the Muhammadiyah Tarjih Center above shows that there are still many local Ulama in certain areas and branches that use narrow-black and white classical-colonial jurisprudence. They hold the views which are not in line with wider disasters jurisprudence which prioritizes lives. In the perspective of neuroscience, this type of clerucs do not have spiritual toughness [63], they only have high religious emotional sensitivity, but do not have adequate religious cognition. As a result, they appear to be radicalized and find it difficult to accept changes, even more so they hold that the way of worship are considered sacred and fixed [64], even though in the midst of Covid-19's emergency conditions.

On the other hand, the emergence of celebrity clerics whose views are viral on social media posed a threat to religious authorities, both the MUI and other religious social organizations including Muhammadiyah [65]. For example, when an Ustad with the initials US said that Corona was a soldier of God, then almost all of his followers justified and even neutralized the statement. In fact, US does not at all represent government institutions (MUI), clerics provisions, especially religious social organizations such as Muhammadiyah. In addition, seeing the virus as God's army can be questioned because genealogically this statement does not have adequate scientific references in Islamic education [66]. However, many Muslims are more obedient to this type of figure [67] and they have become the followers. It sadly not because the celebrity clerics has substantially correct fiqh reasoning. This further strengthens the analysis of the fragmentation of religious authority as a result of the emergence of micro-celebrity clerics [68]. Meanwhile, they should have strengthened and supported government institutions [69] including religious provisions from the authority. In Singapore, for example, although religious institutions do not have a role in policy formulation, religious authority holders also support government policies [70] including in Covid-19 mitigation.

For micro-celebrity clerics, the substantive truth of the contents of the post is not important, but the important thing is to get as many likes and shares as possible so that the post becomes viral on social media [71]. For people who have inadequate religious knowledge, following micro-celebrity clerics is more fun than obeying the authority. This analysis is relevant to the research of Chakravarty et al. in India which states that the phenomenon of “community disobedience” to government rules and religious provision is caused by fragmentation of religious, social, and political authority [68]. In other words, there was an intra-organizational change and idiological moderation in the prevention of Covid-19 [72]. The public no longer fully obeys the government rules and the fatwa of the clerics. But instead they turns to an imitative Islam socialite [67], millennial figures who suddenly appear phenomenal on social media, especially with their viral statements.

4.3. Covid-19 mitigation and education, the perspective of Islamic education neuroscience

The phenomenon of muslim disobeying government and religious provision can be analogous to patients who do not follow a doctor's prescription. This phenomenon can be really dangerous and can be the sign of destruction of Islamic civilization in the future if it remains. Considering this worrying situation, Muhammadiyah realizes that issuing provision and doing humanitarian action won't suffice. It realizes the importance of education in the mitigation of the Covid-19 pandemic so that the reasoning can be understood by people in general.

Education about Disaster Jurisprudence is important because people now is faced with a rapid flow of information that is often in conflicting, both with the government rule and religious provision. This problem is not just about misinformation on social media [73] which spreads terror and fear [20] thereby reducing immunity [74] but rather to the development of spiritual reasoning or science of thought. In this case, the neuroscience of Islamic education can become a new paradigm for conducting Covid-19 mitigation education [75]. Neuroscience is the study of brain performance (the science of thinking) with a multidisciplinary approach, while Islamic education is a conscious effort to transfer knowledge, values, attitudes [76] and optimize the potential of the human brain.

In Islamic education, the education process must involve teachers, the curriculum, and learning media [77]. The question is, which teachers are most appropriate to educate the public about Covid-19 mitigation? What is the curriculum? and how is the learning media used? In this case, the Muhammadiyah’s Council of Religious Affairs (Majelis Tarjih dan Tajdid Muhammadiyah) has prepared all the learning or education tools, both teachers, curriculum and learning media including for Muslims in cyberspace, as has been done by Malaysia [78]. In other words, Muhammadiyah does not only carry out humanitarian actions or medical movements in the form of providing 74 hospitals and religious provisions, but also educational tools for the community.

All public figures and prominent figures in Muhammadiyah are admittedly nation teachers who teach Covid-19 mitigation through religious lectures, mitigation socialization or other relevant activities. This includes medical workers and humanitarian volunteers who spray disinfectants in public places and people's homes. They are all true teachers with real actions to prevent the spread of the virus. Nurse, doctor, and other medical personnel often appear on various information channels and social media to convey messages of healthy behavior facing the Covid-19 pandemic. One message is to wash hands with soap and to stay at home. Likewise many religious figures in Muhammadiyah, always talk about Covid-19 in every religious lecture, both through Television, You Tube, and other Social Media.

The Covid-19 mitigation curriculum includes some learning materials such as book about Disaster Jurisprudence, Guidance for Worship in the Middle of the Pandemic, and a number of religious edicts issued by the Muhammadiyah’s Council of Religious Affairs (Majelis Tarjih dan Tajdid Muhammadiyah). The core activity in this curriculum is to increase istigfar, introspection-evaluation and repentance, so that the spiritual circuit in the brain can be more active. Subsequently, this brain condition will result in attitude changing in which religious provision can be easily heard and instilled. All materials in the curriculum have been formatted digitally so that they are easily distributed to the public through various medias. However, it must be acknowledged that these learning materials might not be as viral. Therefore, learning media innovation is needed to adapt to the characteristics of millennial generation in the new sub-culture society [79]. This has also been done by the Muhammadiyah’s Council of Religious Affairs (Majelis Tarjih dan Tajdid Muhammadiyah) by adding a special educational feature. One of the learning media developed is “Corona Comics” as shown in Fig. 3 a and b below.

Fig. 3.

(a) obeying religious provision by not going to the mosque during pandemics, (b) education about the possibility of changing jummah prayer with zuhur.

Fig. 3 a above illustrates a Muslim who does not comply with government rule and religious fatwas, and insists on wanting to do Friday prayer even though the mosque is closed. While Fig. 3 b explains the education carried out by the mosque imam the people who insist on conducting Friday prayer. In the context of education, the imam is the teacher of the congregation, while the guideline for changing Friday prayers to dluhur is the curriculum. The dialogue between one Jama'ah and imam is a learning process.

In a neuroscience perspective, a dialogic education model that begins with critical questions is a manifestation of the performance of the prefrontal cortex [80]. However, because this critical question is contrary to normative truth (religious fatwa and government appeals), there is one part of the brain that is not functioning maximally, namely the spiritual circuit [81]. This phenomenon is similar to what happens to corrupt brains, where the brain is only normal but not healthy [82]. As a result, they have a high willingness to pray but are not equipped with the necessary knowledge about conducting prayer in an emergency situation.

In terms of graphic design, the learning media above can synergize art, science, and religiosity, so that it has the potential to develop the potential of the brain to the maximum [83]. The colouring of the image impresses enlightenment and courage, combining the design of contemporary comics and modern cartoons [84]. Cinematic and interactive narrative stories make religious comics above ignite the creative imagination of millennial generation [79]. The placement of the Muhammadiyah’s Council of Religious Affairs (Majelis Tarjih dan Tajdid Muhammadiyah) logos in the upper corner, as well as complex but dense social media features in the lower corner, indicate that this learning media carries an important message, namely religious fatwa that must be conveyed to Muslims millennial throughout Indonesia. The efforts to educate Indonesian people carried out by the Muhammadiyah’s Council of Religious Affairs (Majelis Tarjih dan Tajdid Muhammadiyah) are expected to minimize Indonesian citizens' disobedience to government appeals and religious fatwas about Covid-19 mitigation. Comic-cartoon posters with cinematic narratives are expected to ward off micro-celebrity cleric posts that ignore aspects of the truth of information.

5. Conclusion

The Islamic Law of Disaster in the perspective of Muhammadiyah ulama represents disaster management in Islam. Fikih Kebencanaan (Coping with Disaster) in Muhammadiyah perspective is crossing boundaries of time, reconstructing classical Jurisprudence with new interpretations of religious dogma by remaining grounded in Islamic tradition. Amid the Covid-19 pandemic, Fikih Kebencanaan (Coping with Disaster) offers a breakthrough that is different from classical Jurisprudence in general. The preparation of 74 hospitals, the distribution of masks, disinfectant, raising aid funds which has reached 15.4 billion on 2 May 2020 must be understood as a humanitarian action (ukh uwah insaniyah-wasathiyyah), not only for Muslims (ukh uwah Islamiyah), but people in general. On the other hand this is evidence of the Muhammadiyah Vision to enlighten the universe and to advance the country. Likewise with the guidance of worship amid Covid-19 emergencies, which must also be understood with contemporary Jurisprudence so that its implementation is in line with government appeals and advances in science, health and medicine. For micro-celebrity circles who still use classical-colonial jurisprudence, with their viral statements on social media, there are many contradiction to moderate religious understanding, government appeals and scientific advances in the health sector. This study's limitation is that it discusses the role of religious organizations in mitigating Covid-19, especially Muhammadiyah organizations that are large and developing in Indonesia. Future research has an excellent opportunity to develop disaster mitigation concepts that use other perspectives, such as theology, education, and communication sciences.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

Financial support for this study was provided by Universitas Ahmad Dahlan Yogyakarta Indonesia. The authors wish to thank colleagues from universities who assisted in the dissemination of the questionnaire. The author would like to thank to the Muhammadiyah’s Council of Religious Affairs (Majelis Tarjih dan Tajdid Muhammadiyah), Muhammadiyah Covid-19 Command Center: (MCCC), Ms Dyah Aryani Perwitasari and Mr Andri Pranolo who has provided assistance and guidance to the completion of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Interview with Mrs. Farida Fardhani az-Zukhruf, a staff of the Muhammadiyah Tarjih Center who is in charge of administering religious consultation services, May 4, 2020.

Muhammadiyah Tarjih Center (Pusat Tarjih Muhammadiyah) is a supporting institution for the Muhammadiyah’s Council of Religious Affairs (Majelis Tarjih dan Tajdid Muhammadiyah) which collaborates with Ahmad Dahlan University. See more https://pusattarjih.uad.ac.id/.

Interview with Mr. Niki Alma Febriana Fauzi, Head of the Muhammadiyah Tarjih Center, May 4, 2020.

References

- 1.Tian S., et al. Characteristics of COVID-19 infection in Beijing. J. Infect. 2020;80(4):401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sohrabi C., et al. World health organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019Novel coronavirus (COVID-19) Int. J. Surg. 2020;76(2):71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guarner J. Three emerging coronaviruses in two decades the story of SARS , MERS , and now COVID-19, Am. Soc. Clin. Pathol. 2020;153(1):420–421. doi: 10.1093/AJCP/AQAA029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-mandhari A., Samhouri D., Abubakar A., Brennan R. Coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak: preparedness and readiness of countries in the eastern mediterranean region. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2020;26(2):136–137. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hao P., Zhong W., Song S., Fan S., Li X. Is SARS-CoV-2 originated from laboratory? A rebuttal to the claim of formation via laboratory recombination. Emerg. Microb. Infect. 2020;9(1):545–547. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1738279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Djalante R., et al. Review and analysis of current responses to COVID-19 in Indonesia: period of january to March 2020. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2020;6:100091. doi: 10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaharah Zaharah A.W., Kirilova Galia Ildusovna. Impact of corona virus outbreak towards teaching and learning activities in Indonesia. Salam J. Sos. Budaya Syar’i. 2020;7(3):269–282. doi: 10.15408/sjsbs.v7i3.15104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kampf G., Todt D., Pfaender S., Steinmann E. Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their inactivation with biocidal agents. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020;104(3):246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bima G.R.A.P., Jati Jati Bima. Optimalisasi upaya pemerintah dalam mengatasi pandemi covid 19 sebagai Bentuk pemenuhan hak warga negara. Salam J. Sos. Budaya Syar’i. 2020;7(5) doi: 10.15408/sjsbs.v7i5.15316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muhamad A.I., Mushodiq Agus. Peran majelis ulama Indonesia dalam mitigasi pandemi covid-19 (tinjauan tindakan sosial dan dominasi kekuasaan max weber) Salam J. Sos. Budaya Syar’i. 2020;7(5) doi: 10.15408/sjsbs.v7i5.15315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ifdil Ifdil Z.A., Pratiwi Fadli Rima, Suranata Kadek, Zola Nilma. Online mental health services in Indonesia during the COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nurhalimah S. Covid-19 dan hak masyarakat atas kesehatan. Salam J. Sos. Budaya Syar’i. 2020;7(6) doi: 10.15408/sjsbs.v7i6.15324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghufron F. Kompas; Jakarta: 2020. Virus Corona Dan Kegagapan Teologis; p. 5. Mar. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khamis Susie, Ang Lawrence, Welling Raymond. Self-branding, ‘micro-celebrity’ and the rise of Social Media Influencers. Celebrity Studies. 2017;8(2):1–19. doi: 10.1080/19392397.2016.1218292. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/19392397.2016.1218292 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Societal Effects of Corona Conspiracy Theories.

- 16.2020. Influencer Keblinger Ancam Kesehatan Publik Selama Pandemi COVID-19. (Accessed 6 October 2020).

- 17.dan M.T., Muhammadiyah T.P.P. Majelis Tarjih dan Tajdid Pimpinan Pusat Muhammadiyah; Yogyakarta: 2016. Fikih Kebencanaan. [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Fatwā and Islamic Research Council and Muhammadiyah Disaster Management Center, Coping with Disaster: Principle Guidance from an Islamic Perspective. Majelis Tarjih dan Tajdid Pimpinan Pusat Muhammadiyah; Yogyakarta: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashmi Furqan K, et al. Religious Cliché and Stigma: A Brief Response to Overlooked Barriers in COVID-19 Management. Journal of Religion and Health. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10943-020-01063-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peters M.A., Jandrić P., McLaren P. Viral modernity? Epidemics, infodemics, and the ‘bioinformational’ paradigm. Educ. Philos. Theor. 2020;1(1):1–23. doi: 10.1080/00131857.2020.1744226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.2020. How religions and religious leaders can help to combat the COVID-19 pandemic: Indonesia’s experience. (Accessed 6 October 2020).

- 22.2020. COVID-19 Jewish Community Response and Impact Fund Launched. (Accessed 6 October 2020).

- 23.Weinberger-Litman Sarah L. A Look at the First Quarantined Community in the USA: Response of Religious Communal Organizations and Implications for Public Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Religion and Health. 2020:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10943-020-01064-x. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7347758/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alyanak Oğuz. Faith, Politics and the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Turkish Response. Medical Anthropology. 2020;39(5):374–375. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2020.1745482. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01459740.2020.1745482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wildman Wesley J., et al. Religion and the COVID-19 pandemic. Religion, Brain & Behavior. 2020;10(2):115–117. doi: 10.1080/2153599X.2020.1749339. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/2153599X.2020.1749339 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levin Jeff. The Faith Community and the SARS-CoV-2 Outbreak: Part of the Problem or Part of the Solution? Journal of Religion and Health. 2020:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10943-020-01048-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.2020. Comparing Tablighi Jamaat and Muhammadiyah Responses to COVID-19. (Accessed 6 October 2020).

- 28.McLaughlin Levi. Japanese Religious Responses to COVID-19: A Preliminary Report. The Asia Pacific-Journal. 2020;18(9) https://apjjf.org/2020/9/McLaughlin.html [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solinska-Nowak A., et al. An overview of serious games for disaster risk management-prospects and limitations for informing actions to arrest increasing risk. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018;31(11):1013–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akter S. Social cohesion and willingness to pay for cyclone risk reduction: the case for the coastal embankment improvement project in Bangladesh. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020;48(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101579. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iuchi K., Mutter J. Governing community relocation after major disasters: an analysis of three different approaches and its outcomes in Asia. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2020;6(11–8):100071. doi: 10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rokib M. The significant role of religious group's response to natural disaster in Indonesia: the case of Santri Tanggap Bencana (Santana) Indones. J. Islam Muslim Soc. 2012;2(1):53–77. doi: 10.18326/ijims.v2i1.53-77. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bremner L. Sedimentary logics and the Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh. Polit. Geogr. 2020;77(1):102109. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.102109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parmar P.K., Leigh J., Venters H., Nelson T. Violence and mortality in the northern Rakhine state of Myanmar, 2017: results of a quantitative survey of surviving community leaders in Bangladesh. Lancet Planet. Heal. 2019;3(3):e144–e153. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Al Eid Nawal A., Arnout Boshra A. Crisis and disaster management in the light of the Islamic approach: COVID‐19 pandemic crisis as a model (a qualitative study using the grounded theory) Journal of Public Affairs. 2020 doi: 10.1002/pa.2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Djalante R., et al. Review and analysis of aurrent responses to COVID-19 in Indonesia: period of january to March 2020. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2020;6(1–9):100091. doi: 10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin Q., et al. A conceptual model for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in wuhan, China with individual reaction and governmental action. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;93:211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Freedman D.O. Isolation , quarantine , social distancing and community containment: pivotal role for old-style public health measures in the novel coronavirus ( 2019-nCoV ) outbreak. J. Trav. Med. 2020;1(1):1–4. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rusli Abdul Rahman. Studi Terhadap Kata-kata yang Semakna dengan Musibah dalam Alquran. Journal Analytica Islamica. 2013;2(2) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mardan Mardan. The Qur’anic Perspective on Disaster Semiotics. Jurnal Adabiyah. 2018;18(2) [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lifintseva Tatyana P., et al. Fitnah: The Afterlife of a Religious Term in Recent Political Protest. Religions. 2015;6(2):527–542. doi: 10.3390/rel6020527. https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/6/2/527 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fatić Almir. Pojam fasād u Kur’anu. Analighb. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khafidhoh Khafidhoh. Teologi Bencana dalam Perspektif M. Quraish Shihab. Esensia. 2013;14(1):37–60. doi: 10.14421/esensia.v14i1.749. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanjung Abdul Rahman Rusli. Musibah dalam Perspektif Alquran: Studi Analisis Tafsir Tematik. Analytica Islamica. 2012;1(1):148–162. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raskin J.D. Thinking, feeling, and being human. J. Constr. Psychol. 2013;26(3):181–186. doi: 10.1080/10720537.2013.787323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Majelis Tarjihd dan Tajdid Pimpinan Pusat Muhamamdiyah. Suara Muhammadiyah; Yogyakarta: 2018. Himpunan Putusan Tarjih Muhammadiyah Jilid 3. [Google Scholar]

- 47.N. A. F. Fauzi and Ayub Fikih informasi: Muhammadiyah's perspective on guidance in using social media. Indones. J. Islam Muslim Soc. 2019;9(2):267–293. doi: 10.18326/ijims.v9i2.267-293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fauzi N.A.F. Nalar Fikih Baru Muhammadiyah: membangun paradigma hukum Islam yang holistik. Afkaruna. 2019;15(1):19–42. doi: 10.18196/AIIJIS.2019.0093.19-41. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sina I. 1948. Al-Isyarat wa Thanbihat. Kairo. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Handayani A.B., Suyadi S. 2019. Relevansi Konsep Akal Bertingkat Ibnu Sina dalam Pendidikan Islam di Era Milenial. vol. 8, no. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Donoghue G.M., Horvath J.C. Translating neuroscience, psychology and education: an abstracted conceptual framework for the learning sciences. Cogent Educ. 2016;3(1):1–10. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2016.1267422. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abdullah M.A. Religion, science, and culture: an integrated, interconnected paradigm of science. Al-Jami’ah J. Islam. Stud. 2015;52(1):175. doi: 10.14421/ajis.2014.521.175-203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fouché N. A contemporary review of understanding the religious and cultural diversity of patients dying or who have died in the intensive care unit. A South African perspective nicola. Int. J. Africa Nurs. Sci. 2019;10:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijans.2019.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Norman Y.S.L., Denzin K. second ed. Sage Publication. Pvt. Ltd; India: 1997. Handbook of Qualitative Research. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Creswell J. Pearson Edcation Inc.; London: 2010. Educational Research: Planing, Conducting, and Evaluating Qualitative and Quantitative. [Google Scholar]

- 56.2020. Tuntunan Ibadah dalam Kondisi Darurat Covid-19. (Accessed 6 October 2020).

- 57.Muhammadiyah . 2020. Muhammadiyah Covid-19 Command Center (MCCC) [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Laar E., van Deursen A.J.A.M., van Dijk J.A.G.M., de Haan J. Measuring the levels of 21st-century digital skills among professionals working within the creative industries: a performance-based approach. Poetics. 2020;42(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2020.101434. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Andersen R.A., Kellis S., Klaes C., Aflalo T. Toward more versatile and intuitive cortical brain-machine interfaces. Curr. Biol. 2014;24(18):R885–R897. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.07.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.KeijiTanaka K.C., Wan Xiaohong. Brain mechanisms of intuitive problem solving in board game experts. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2014;94(2):162. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2014.08.707. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Saeednia Y., Nor M.M.D. Measuring hierarchy of basic needs among adults. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013;82(1):417–420. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.285. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Manoj Kumar Sharma S.N., Chaturvedi Santosh K. Technology use expression of Maslow's hierarchy need. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020;48(1) doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2019.101895. 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Norenzayan A.K.W.A. ‘Spiritual but not religious’: cognition, schizotypy, and conversion in alternative beliefs. Cognition. 2017;165(8):137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2017.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hamid N., et al. Neuroimaging ‘will to fight’ for sacred values: an empirical case study with supporters of an Al Qaeda associate. 2019;6(181585):1–13. doi: 10.1098/rsos.181585. royalsocietypublishing.org/journal/rsos. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Usher B. Twitter and the celebrity interview. Celebr. Stud. 2015;6(3):306–321. doi: 10.1080/19392397.2015.1062641. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Suyadi and Sutrisno A genealogycal study of Islamic education science at the faculty of Ilmu Tarbiyah Dan Keguruan UIN Sunan Kalijaga. Al-Jami’ah. 2018;56(1):29–58. doi: 10.14421/ajis.2018.561.29-58. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Raun T. Capitalizing intimacy: new subcultural forms of micro-celebrity strategies and affective labour on YouTube. Convergence. 2018;24(1):99–113. doi: 10.1177/1354856517736983. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chakravarty S., Fonseca M.A., Ghosh S., Kumar P., Marjit S. Religious fragmentation, social identity and other-regarding preferences: evidence from an artefactual field experiment in India. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2019;82(11):1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fogg K.W. Reinforcing charisma in the bureaucratisation of Indonesian Islamic organisations. J. Curr. Southeast Asian Aff. 2018;37(1):117–140. doi: 10.1177/186810341803700105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pasuni A. Negotiating statist Islam: fatwa and state policy in Singapore. J. Curr. Southeast Asian Aff. 2018;37(1):57–88. doi: 10.1177/186810341803700103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.WonKim J. They liked and shared: effects of social media virality metrics on perceptions of message influence and behavioral intentions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018;84(1):153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.01.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sindre G.M. From secessionism to regionalism: intra-organizational change and ideological moderation within armed secessionist movements. Polit. Geogr. 2018;64(1):23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2018.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.H. R. Keonyoung Park Social media xoaxes, political ideology, and the role of issue confidence. Telematics Inf. 2019;36(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2018.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Suyadi S. Immunology pedagogical psychology of Pesantren Kindergarten: multicase study at Pesantren Kindergarten in Yogyakarta. Addin. 2019;13(1):57. doi: 10.21043/addin.v13i1.3510. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Suyadi S. Hybridization of Islamic education and neuroscience: transdisciplinary studies of ’Aql in the Quran and the brain in neuroscience. Din. Ilmu. 2019;19(2):237–249. doi: 10.21093/di.v19i2.1601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Abdullah Azis, Masruri Siswanto, Bashori Khoiruddin. Islamic Education and Human Construction in the Quran. International Journal of Education and Learning. 2019;1(1):27–32. doi: 10.31763/ijele.v1i1.21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sutrisno, Suyadi . Rosda Karya; Bandung: 2015. Desain Kurikulum Pendidikan Tinggi Mengacu KKNI. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rahman A.A., Hashim N.H., Mustafa H. Muslims in cyberspace: exploring factors influencing online religious engagements in Malaysia. Media Asia. 2015;42(1–2):61–73. doi: 10.1080/01296612.2015.1072343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Widodo Hendro, Suyadi Suyadi. Millennialization of Islamic education based on neuroscience in the third generation university in Yogyakarta Indonesia. Qudus Int. J. Islam. Stud. 2019;7(1):173–202. doi: 10.21043/qijis.v7i1.4922. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sherwood Lauralee. 2012. Fisiologi Manusia, dari Sel ke Sistem, Alih Bahasa: Brahm U. Pendit, Edisi VI. Jakarta: Penerbit Buku Kedokteran EGC. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pasiak T. Manado: POPS-LPPM Unsrat; 2018. Spiritual Neuroscience: Behavioral Implication in Health and Leadership. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Suyadi R.D.R.M., Sumaryati, Hastuti Dwi, Yusmaliana Desfa. Constitutional piety: the integration of anti-corruption education into Islamic religious learning based on neuroscience. J-PAI J. Pendidik. Agama Islam. 2019;6(1):38–46. doi: 10.18860/jpai.v6i1.8307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Suyadi S. The synergy of arts, science, and Islam in early childhood learning in Yogyakarta. Tarbiya J. Educ. Muslim Soc. 2018;5(1):30–42. doi: 10.15408/tjems.v5i1.7934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Klaehn J. "Bold and bright, combining the aesthetics of comics and saturday morning cartoons”: an interview with comic cook artist and writer tom scioli. J. Graph. Nov. Comics. 2019 doi: 10.1080/21504857.2019.1622583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]