Abstract

A esterase gene was characterized from a halophilic bacterium Chromohalobacter canadensis which was originally isolated from a salt well mine. Sequence analysis showed that the esterase, named as EstSHJ2, contained active site serine encompassed by a conserved pentapeptide motif (GSSMG). The EstSHJ2 was classified into a new lipase/esterase family by phylogenetic association analysis. Molecular weight of EstSHJ2 was 26 kDa and the preferred substrate was p-NP butyrate. The EstSHJ2 exhibited a maximum activity at 2.5 M NaCl concentration. Intriguingly, the optimum temperature, pH and stability of EstSHJ2 were related to NaCl concentration. At 2.5 M NaCl concentration, the optimum temperature and pH of EstSHJ2 were 65 ℃ and pH 9.0, and enzyme remained 81% active after 80 ℃ treatment for 2 h. Additionally, the EstSHJ2 showed strong tolerance to metal ions and organic solvents. Among these, 10 mM K+, Ca2+ , Mg2+ and 30% hexane, benzene, toluene has significantly improved activity of EstSHJ2. The EstSHJ2 was the first reported esterase from Chromohalobacter canadensis, and may carry considerable potential for industrial applications under extreme conditions.

Keywords: Chromohalobacter canadensis, Esterase, Halotolerant, Characteristics

Introduction

Lipolytic enzymes, including esterases and lipases, mainly catalyze the hydrolysis and synthesize ester bonds. Lipolytic enzymes carry a conserved motif (Gly-X-Ser-X-Gly) and catalytic active site serine. Based on the specific amino acid sequences and fundamental biological properties, these enzymes can be divided into eight families (Arpigny et al. 1999). Lipolytic enzymes exist in all organisms, and primarily commercial-grade lipidolytic enzymes are acquired from microorganisms. Microbial lipolytic enzymes are the third largest industrial biocatalyst after amylase and protease (Kapoor et al. 2012; Schreck et al. 2014).

Owing to their versatile catalytic properties, microbial esterases are used in industries as diverse as pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, food detergents, leather, textiles, paper and biodiesel (Gupta et al. 2004; Hasan et al. 2006). Among the microbial esterases, halotolerant esterases from halophilic microorganisms are of highest value. The high-salt environment favors the multiplication of halophilic microorganisms, and therefore halotolerant esterases are mostly tolerant to harsh conditions (cold, hot, high salt level, organic solvents). These properties are required for specific industrial processes such as novel halotolerant thermoalkaliphilic esterase industries, synthesis of biopolymers, biodiesel production, bioremediation and waste treatment (Barone et al. 2014; López-López et al. 2014; Moreno et al. 2016). Halotolerant esterases can make these processes more efficient and environmentally friendly (Bornscheuer 2002).

In recent decades, many novel microbial salt-tolerant esterases have been isolated and functionally characterized. Most of these microbes come from marine and soil environments (Sana et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2013; Dalmaso et al. 2015; Castilla et al. 2017; Huo et al. 2017; Ke et al. 2018), however, microbial diversity in high-salt environment particulary from salt mine remained elusive. Salt mines are salty stratum mainly constituted by the evaporation of ancient inland ocean, while salt wells are formed by salty stratum dissolved in the water.

Shenhaijing salt well is located in the Triassic strata of Zigong, Sichuan province of the China. Shenhaijing salt well is the world's first large well with over a kilometer depth. It was dug in A.D.1835 and is continuously producing well salt. The relatively isolated high-salt environment in salt wells led to the evolution of unique physiological characteristics of microorganisms, which was expected to produce enzymes with superior properties. Except identification of lipase and transaminase, limited investigations have been made on the microbial enzymes in salt mine (Chauhan et al. 2013; Kelly et al. 2014). Here, we cloned a salt-tolerant esterase gene from Chromohalobacter canadensis isolated from Shenhaijing salt well. Amino acid sequence alignment indicated that the esterase, named EstSHJ2, belonged to a new family of esterases. The EstSHJ2 exhibited excellent halotolerant, thermostability and organic solvents-tolerance. Our research enriched the microbial functional enzyme resources in salt mine and provide a basis for utilization of halotolerant esterase in the industries.

Materials and methods

Materials

The substrates p-nitrophenyl esters (C2-C16) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Ex-Taq DNA polymerase and T4 DNA ligase were obtained from TaKaRa (Dalian, China). Restriction enzymes were obtained from NEB (USA), bacteria genome kits, plasmid purification kit and gel purification kits were purchased from Qiagen (USA). Nickel affinity chromatography columns were purchased from Merk (USA). Primers synthesis and gene sequencing were performed by Invitrogen (Shanghai, China). All other reagents were of analytical grade and are commercially available.

Strains and vectors

The halophilic bacterium SHJ2 was collected from Shenhaijing salt well, an ancient salt well located in Zigong, Sichuan province in China. SHJ2 was identified as Chromohalobacter canadensis by 16S rDNA sequence analysis (GenBank accession number ADF51938.1). The SHJ2 grew in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium with 10% NaCl at 37 ℃. The E. coli strains including DH5α and BL21 (DE3) were obtained from TaKaRa (Dalian, China). The pMD19-T and pET28a plasmids were purchased from Takara (Dalian, China) and were used for gene cloning and protein expression, respectively.

Gene cloning

Genomic DNA of SHJ2 was obtained using bacteria genome kit, and the esterase gene was amplified using following primers.

Est Sense: 5- GGATCCATGCTGGTGGCGCCCGTGGCAAACA -3;

Est Anti:5- AAGCTTTTATGTGGATTCGTCAGAGCGCGTTG -3.

The PCR was performed according to thermoprofile of 94 ℃ 5 min, 35cycles of 94 ℃ for 30 s, 54 ℃ for 30 s and 72 ℃ for 2 min, and 72 ℃ for 10 min. The PCR amplified fragments were cloned into pMD19-T vector and verified by sequencing.

Expression and purification of esterase

The plasmids from positive clone were prepared using plasmid purification kit. Plasmid was digested by BamHI and HindIII and was ligated into pET28a using T4 ligase. Ligated products were transformed into the E. coli BL21 (DE3). The cells were cultured at 20 °C for 12 h followed by the addition of 0.25 mM IPTG to induce protein expression. The induction was performed at the OD600 of 0.4–0.6 at 37 °C in LB medium. Cells were harvested and treated by lysozyme, and the lysate was centrifuged and the supernatant was loaded on nickel affinity chromatography columns. Protein expression was detected by SDS-PAGE. Fractions containing the recombinant protein were pooled and dialyzed overnight against 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH7.5) containing 5% glycerol. The purified protein was stored at – 20 °C.

Sequence analysis

Protein sequence was analyzed for the similarity using the BLASTP program. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using CLUSTAL-W and GENEDOC algorithms (Aiyar 2000). Phylogenetic tree was constructed using Neighbor-Joining method by MEGA 5.0 software with 1000 bootstrapping replicates (Tamura et al. 2011).

Structural modeling

Proteins selected for modeling were searched using BLASTP against the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The three-dimensional structural model was built by the SWISS-MODEL (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/) based on the esterase from Yersinia enterocolitica, (PDB code: 4FLE). The quality of model was evaluated by Phyre2 server (https://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/phyre2/html/page.cgi?id=index). PyMOL (PyMOL molecular graphics system, Schrödinger, LLC) was used to visualize and annotate the predicted model.

Esterase assay

Colorimetric method was performed to measure activity of the esterase. The p-nitrophenyl butyrate (p-NPB) was used as a substrate. The reaction mixture was composed of 0.7 mL Tris–HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 8.0), 0.1 mL purified enzyme, and 0.2 mL p-NPB solution which was dissolved in isopropanol to 10 mM. Mixture without enzymes was used as control. After incubating at 37 °C for 10 min, mixture was centrifuged and detected at 410 nm for measuring the release of product p-nitrophenol (p-NP). One esterase unit (U) was defined as the amount of enzyme releasing 1 µmol p-NP per minute under assay conditions.

Characterization of purified esterase

Substrate specificity and kinetic parameters

The substrate specificity of esterase was confirmed by colorimetric method as described above. The p-nitrophenyl (p-NP) esters with different chain lengths (C2-C16) were used as substrates. The activity with p-NPB (p-NP butyrate) as substrate was defined as 100%.

The kinetic parameters of EstSHJ2 were measured using varying concentrations of p-NPB (0.5–50 mM). The Km and kcat parameters were determined using Lineweaver–Burk linearization using Michaelis Menten equation.

Effect of salt, temperature and pH on esterase activity and stability

The effect of salt on esterase activity was studied using p-NPB as substrate under different NaCl concentrations (0–5 M). The optimum temperature and pH of EstSHJ2 were determined by measuring esterase activity at different temperatures (30–80 °C) and pH (5.0–10.0) in the presence of different salt concentrations (0.5, 2.5, 4.5 M). Reaction mixtures without enzyme were used as control.

Thermo stability and pH stability of EstSHJ2 were evaluated by measuring residual activity of enzyme which was pretreated in various pH (4.0–11.0) or at different temperatures (40–80 ℃) for 2 h in the presence of different salt concentrations.

Effect of metal ions on esterase activity

The reaction mixture containing EstSHJ2 and various ions was incubated for 1 h at 35 ℃ in 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 8.0). Metal ions including K+, Fe2+, Mg2+, Mn2+, Zn2+, Cu2+, Al3+, Ba2+, Ni2+ and Ca2+ were measured with different concentration of esterase (1 mM and 10 mM). Remaining activity was measured as mentioned above and esterase activity in the absence of ions was set as 100% for comparison purposes.

Effect of organic solvents on esterase activity

The effect of organic solvents on EstSHJ2 was investigated by determining the residual activity of enzymes in the presence of various organic solvents at different concentrations (10% and 30%). The reaction mixture was incubated for 30 min at 35 ℃. Reaction solution without any organic solvent was used as control (100% relative activity).

Effect of surfactants and reagents on esterase activity

Esterase was incubated with surfactants or reagents in 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 8.0) at 35 ℃ for 1 h. Residual activity was determined as mentioned above. Esterase activity in the absence of any surfactants or reagents was considered as control (100%). The surfactants including Triton X-100, Tween-80, Tween-20, CTAB and SDS with concentration of 1% and 10% (v/v) were used. The reagents including PMSF, EDTA, β-mercaptoethanol, DTT and urea with concentration of 1 mM and 10 mM concentration were used.

Results

Cloning and sequence analysis of EstSHJ2

The putative esterase encoding gene was amplified by PCR from the genome of Chromohalobacter canadensis with a single band of 500–750 bp in size. The sequencing analysis showed a putative protein with an ORF of 646 bp encoding for 213 amino acid residues. The protein, named EstSHJ2, had a theoretical molecular mass of 25.8 KDa and a deduced pI of 4.73. No N-terminus signal peptide was identified in the EstSHJ2 gene. The sequence of EstSHJ2 was submitted to GenBank and is available under the accession number of MF769788.

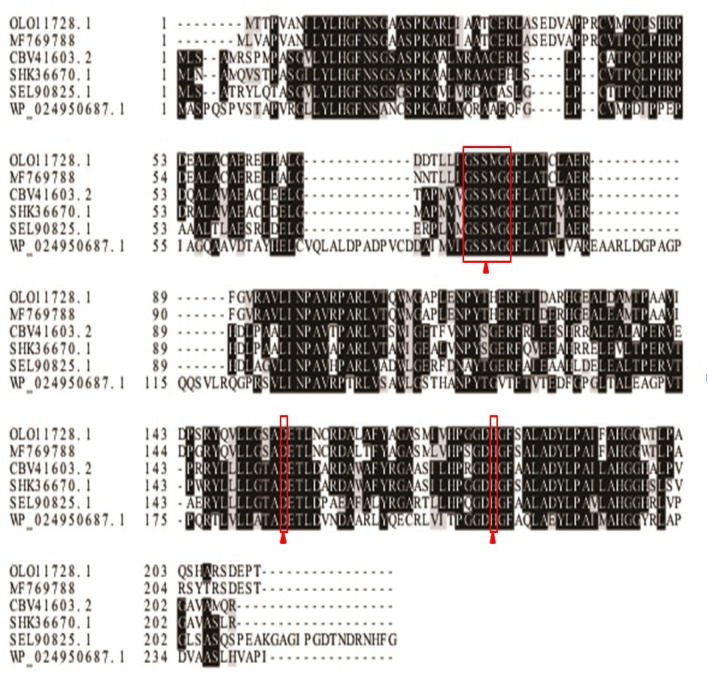

EstSHJ2 was aligned to other esterase available from the GenBank database. The EstSHJ2 exhibited 64% similarity with hypothetical esterase from Chryseobacterium sp. StRB126 (WP 045,498,424) and Chryseobacterium oranimense (WP 040,994,229) and 63% similarity with Epilithonimonas sp. FH1 (WP 034,968,260.1), Chryseobacterium gregarium (WP 027,388,683.1), Epilithonimonas lactis (WP 034,974,989.1), and Chryseobacterium formosense (WP 034,676,217.1). Multiple sequence alignment analysis showed that EstSHJ2 gene contained a catalytic triad which was highly conserved in lipolytic enzymes of the α/β hydrolase superfamily. The catalytic triad included Ser78, Asp157 and His182. The Ser was encompassed by a conserved pentapeptide motif GSSMG (Gly76-Ser-Ser-Met-Gly), whereas the Asp157 was located in the conserved DET motif, and His182 was in the C-terminal conserved HGF motif (Fig. 1). Based on these finding, EstSHJ2 was classified as member of the esterase family.

Fig. 1.

Multiple sequences alignment of EstSHJ2 with homologues. Multiple alignment of amino acid sequences of EstSHJ2 and other esterase. The numbers on the left are the residue numbers of the first amino acid in each line. Identical residues are shaded in black, and conserved residues are shaded in gray. Abbreviations and accession numbers of the esterase are as follows: Chromohalobacter japonicus (MF769788 and OLO11728.1), Halomonas elongata (CBV41603.2), Halomonas caseinilytica (SHK36670.1), Halomonas daqiaonensis (SEL90825.1), and Cobetia crustatorum (WP_024950687.1)

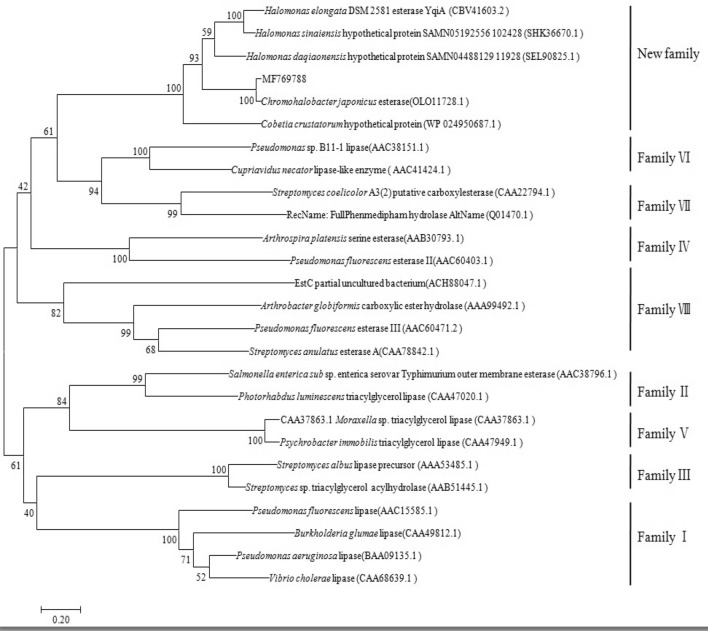

The phylogenetic analysis of EstSHJ2 and other known typical lipases/esterases from other families was constructed. Phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2) showed that EstSHJ2 and five other homologous esterase and hypothetical proteins formed a new lipase/esterase family, instead of belonging to the existing eight lipase/esterase families.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of EstSHJ2 within lipase/esterase families

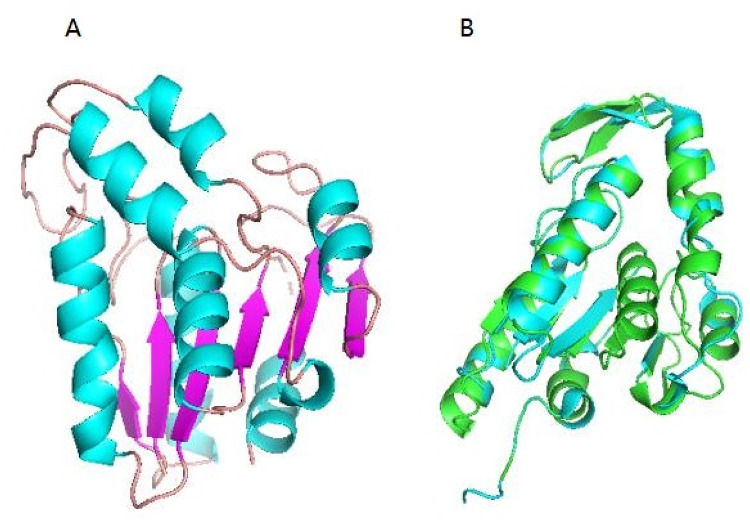

Structural modeling of EstSHJ2

The 3D structure of EstSHJ2 was modeled using the SWISS-MODEL server. Analysis of the predicted model by the Phyre2 server showed that over 89% of residues were located in the reasonable region, and the homology was as high as 34.04%, proving that the homology is reliable. The structure analysis showed a typical α/β-hydrolase folding as found for other esterases, in which parallel β strands were surrounded by several α helices (Holmquist, 2000) (Fig. 3A). The structural model of EstSHJ2 superimposed substantially with most related homologs, including YqiA (Forouhar et al. 2012) (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

3D structure model of EstSHJ2 and structural superimposition with other homologous esterases. (A) Cartoon representation of EstSHJ2. The α helices and β strands are colored in blue and purple, respectively. (B) The structural superposition of EstSHJ2 (green) and YqiA (blue, PDB: 4FLE)

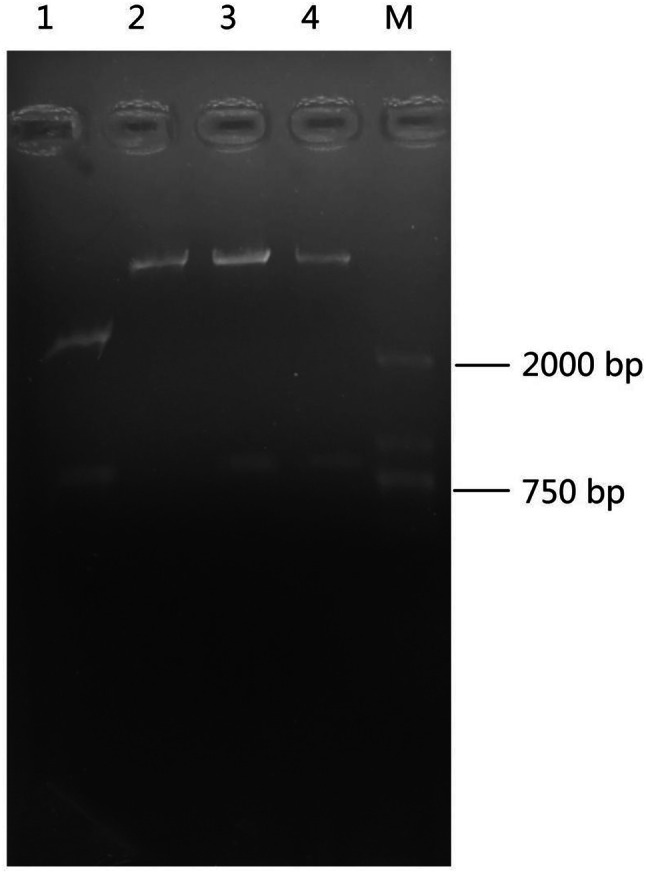

Expression and purification of EstSHJ2

EstSHJ2 gene was ligated in the vector pET28a to construct a plasmid called pET28a-EstSHJ2. The vector pET28a-EstSHJ2 was confirmed by restriction enzyme digestion and an expected band of EstSHJ2 gene was noticed (Fig. 4). Thereafter, EstSHJ2 gene expression was inducible in E. coli BL21 (DE3) by adding 0.25 mM IPTG at 20 ℃ (Fig. 5a). Cell supernatant was purified using His-tag affinity chromatography. As expected, the SDS PAGE analysis showed a band of molecular mass of 26 KDa (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 4.

The confirmation of recombinant vector pET28a-EstSHJ2 by restriction enzyme of BamHI and HindIII. M: DNA marker; lane 1: pMD19-T- EstSHJ2; lane 2: pET28a; lane 3,4: pET28a- EstSHJ2

Fig. 5.

SDS-PAGE analysis of expression (a) and purification (b) of EstSHJ2. M: Protein molecular weight marker; lane 1: non-induced cell supernatants; lane 2: induced cell supernatants; lane 3: purified EstSHJ2

Characterization of Purified Esterase

Substrate specificity and kinetic parameters of EstSHJ2

The p-nitrophenyl (p-NP) esters with different carbon chain lengths were used as substrates to confirm substrate specificity. As shown in Fig. 6, the activity of EstSHJ2 using short p-NP esters (< C6) as substrates was significantly higher than that of using middle-to-long chains (> C10) esters. These results suggested that the short chain p-NP esters were preferred substrates for EstSHJ2. The maximal relative activity was observed using C4 esters (p-NP butyrate, pNPB) as substrates, and almost no activity was noticed using C14 and C16 esters. The kinetic parameters Km and kcat of EstSHJ2 were 1.8 mM and 13.2 s−1 using p-NPB as substrate respectively. The catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) was 7.33 mM−1 s−1.

Fig. 6.

Substrate specificity of EstSHJ2 to different chain lengths of p-nitrophenyl esters. C2: p-NP acetate; C4: p-NP butyrate; C6: p-NP caproate; C8: p-NP caprylate; C10: p-NP caprate; C12: p-NP laurate; C14: p-NP myristate; C16: p-NP palmitate

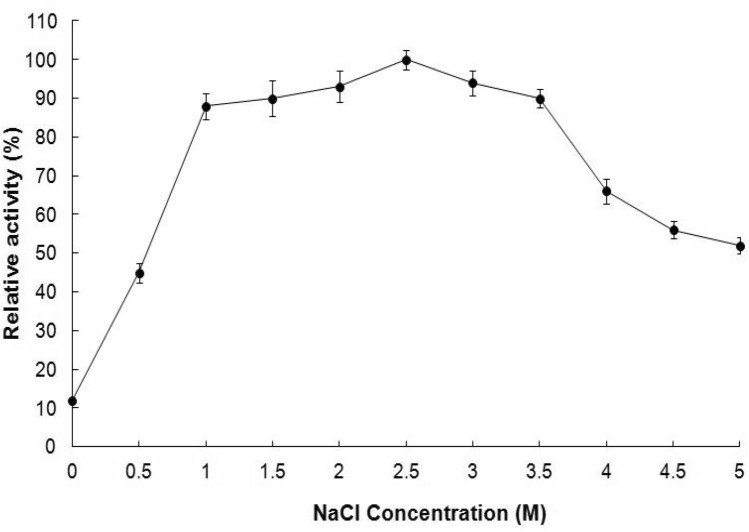

Effect of salt, temperature and pH on EstSHJ2 activity and stability

Activity of EstSHJ2 was increased with increasing salt concentration (Fig. 7). EstSHJ2 remained high level activity in the range of 1.0–3.5 M NaCl and exhibited highest activity at 2.5 M NaCl. Enzymatic activity was decreased gradually above 4.0 M NaCl and was maintained at 52.1% when 5 M NaCl was used. Although EstSHJ2 showed activity in the absence of salt, the activity was very low. This suggest that the enzyme was high salt tolerant and its activity was dependent on certain concentration of salt.

Fig. 7.

Effect of NaCl concentration on EstSHJ2 activity.The highest activity of the enzyme was defined as 100%

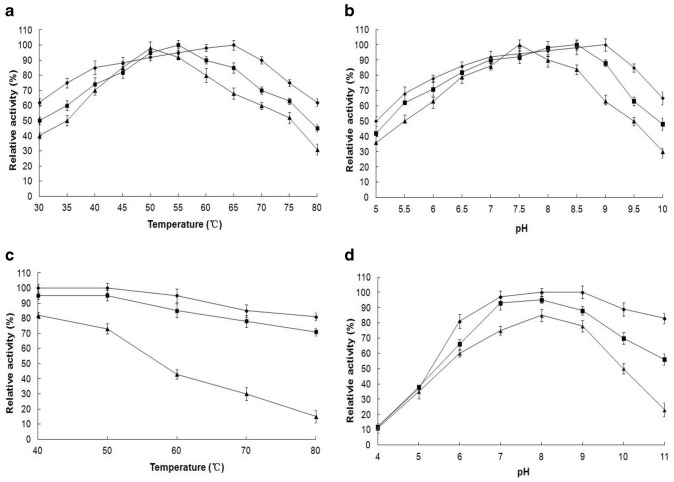

The effects of temperature and pH on EstSHJ2 activity were studied at different salt concentrations. The results showed that effect of temperature on activity was related to salt concentration (Fig. 8a). The optimum temperature for EstSHJ2 was 65 ℃at 2.5 M NaCl, 55 ℃ at 0.5 M NaCl and 50 ℃ at 4.5 M NaCl, respectively. At 80 ℃, the activity remained 62% at 2.5 M NaCl, decreased to 45% and 31% at 0.5 M and 4.5 M NaCl respectively.

Fig. 8.

Effect of temperature (a) and pH (b) on EstSHJ2 activity, thermostability (c) and pH stability (d) of EstSHJ2 at different NaCl concentration. 0.5 M NaCl (■), 2.5 M NaCl (◆), 4.5 M NaCl (▲)

Similarly, salt concentration also affected the optimal pH of EstSHJ2 (Fig. 8b). The optimum pH of enzyme was 9.0 at 2.5 M NaCl, while the optimum pH decreased to 8.5 at 0.5 M and 7.5 at 4.5 M NaCl, respectively. On the other hand, in the presence of 2.5 M NaCl, the enzyme activity at various pH was higher than that in the presence of 0.5 M and 4.5 M NaCl.

Thermostability and pH stability of EstSHJ2 were studied also at different salt concentrations. The cumulative results showed that salt influenced thermostability of EstSHJ2. The EstSHJ2 retained 81% activity after 80 ℃ treatment in the presence of 2.5 M NaCl, which was greater in the presence of 0.5 M NaCl (71%). However, 4.5 M NaCl greatly reduced thermostability of EstSHJ2, and activity sharply decreased to 15% after 80 ℃ treatment (Fig. 8c).

On the other hand, the activity of acid-treated enzyme remained comparable at three different NaCl concentrations. While under alkali treatment, 2.5 m NaCl significantly promoted the pH stability of EstSHJ2. After treatment at pH11, the EstSHJ2 activity remained 83% at 2.5 M NaCl, 56% at 0.5 M NaCl, and only 23% at 4.5 M NaCl concentrations (Fig. 8d).

Effect of metal ions, organic solvents, chemical reagent and surfactants on EstSHJ2 activity

Effects of metal ions on EstSHJ2 activity is outlined in the Table 1. All tested metal ions at 1 mM concentrations failed to inhibit EstSHJ2 activity. However, effect of metal ions at 10 mM on EstSHJ2 activity was diverse. Ions such as K+, Ca2+ and Mg2+ significantly enhanced enzyme activity, and highest activity (264%) was noticed at 10 mM concentration of KCl. The Ba2+, Zn2+ and Mn2+ showed little effect on EstSHJ2, whereas Cu2+, Fe2+, Al3+ and Ni2+ have reduced enzyme activity by 21%–36%.

Table 1.

Effect of metal ions on EstSHJ2 activity

| Metal ions | Relative activity (%) | Metal ions | Relative activity (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 mM | 10 mM | 1 mM | 10 mM | ||

| K+ | 103 | 264 | Ba2+ | 101 | 101 |

| Ca2+ | 108 | 178 | Cu2+ | 103 | 79 |

| Mg2+ | 104 | 155 | Fe2+ | 105 | 70 |

| Mn2+ | 106 | 98 | Ni2+ | 102 | 64 |

| Zn2+ | 102 | 101 | Al3+ | 103 | 68 |

Analysis indicated that hexane, toluene and benzene at concentration of 10%–30% promoted activity of EstSHJ2, and activity increased to 156%, 135% and 126% when concentration reached 30% (Table 2). The enzymatic activity remained stable in the presence of ethyl acetate and propanol at concentration of 10%–30%. There was no significant change in EstSHJ2 activity at 10% concentration of acetone, methanol, ethanol, acetonitrile and DMSO. However, with the increasing concentration of these solvents, enzymatic activity was decreased, however, remained above 55%.

Table 2.

Effect of organic solvents on EstSHJ2 activity

| Organic solvent | Relative acticvity (%) | Organic solvent | Relative acticvity (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10%(v/v) | 30%(v/v) | 10%(v/v) | 30%(v/v) | ||

| Toluene | 107 | 135 | Methanol | 95 | 64 |

| Benzene | 106 | 126 | Propanol | 103 | 97 |

| Acetonitrile | 98 | 61 | Ethyl acetate | 105 | 101 |

| Hexane | 110 | 156 | Ethanol | 102 | 58 |

| Acetone | 103 | 78 | DMSO | 93 | 56 |

A marked increase in the activity of EstSHJ2 was observed when non-ionic surfactants such as Triton X-100, Tween-20 and Tween-80 were applied. A maximum of 178% increase in the performance was observed in the presence of 10% Triton X-100 (Table 3). However, the enzyme activity decreased to 23%, 31% and 16% at 10% SDS, CTAB and 10 mM urea, respectively. Additionally, PMSF completely inhibited the activity at 10 mM concentration whereas DTT and β-mercaptoethanol at 10 mM concentration significantly decreased enzyme activity to 11% and 36%. The EDTA had little influence on EstSHJ2.

Table 3.

Effect of chemical reagents and surfactants on EstSHJ2 activity

| Surfactants | Relative activity (%) | Reagents | Relative activity (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1% | 10% | 1 mM | 10 Mm | ||

| Triton-X100 | 121 | 178 | PMSF | 5 | 0 |

| Tween20 | 106 | 131 | EDTA | 100 | 95 |

| Tween80 | 110 | 144 | β-mercaptoethanol | 78 | 36 |

| SDS | 85 | 23 | DTT | 65 | 11 |

| CTAB | 74 | 31 | Urea | 52 | 16 |

Discussion

Extremozymes, produced by extremophiles, have attracted considerable attention in biotechnological field due to their novel and diverse properties. In the present study, we cloned and characterized a salt-tolerant esterase (EstSHJ2) from moderately halophilic bacteria (characterized as Chromohalobacter Canadensis) which was isolated from ancient salt well of Zigong city, The PR China. Most of reported halotolerant esterases are isolated from halophilic archaea (Camacho et al. 2009; Müller-Santos et al. 2009; Ozcan et al. 2012) and marine bacteria such as Thalassospira sp (De Santi et al. 2016), Pelagibacterium sp (Jiang et al. 2012), Zunongwangia profunda (Rahman et al. 2016), Psychrobacter pacificensis (Wu et al. 2015), Pseudomonas oryzihabitans (Wang et al. 2016a, b) and Bacillus (Sana et al. 2007). To our knowledge, the EstSHJ2 is the first reported halotolerant esterase from Chromohalobacter canadensis.

EstSHJ2 protein included a pentapeptide consensus sequence, Gly-X-Ser-X-Gly, and a catalytic triad (Ser-Asp-His), which were highly conserved in lipase/esterase superfamily (Akoh et al. 2004). Interestingly, phylogenetic analysis showed that EstSHJ2 did not belong to any of the eight lipase/esterase families, highlighting that EstSHJ2 and putative homologs could be classified into a new family. In recent years, several novel esterases from ocean and soil microbes have been identified which cannot be clustered in either of eight family groups (Wu et al. 2013a, b; Akoh et al. 2004; Fang et al. 2014) and soil (Wang et al. 2013; Castilla et al. 2017) microbes. Our research suggested that, as a unique saline environment from ocean to land, salt wells were also potential resources for developing novel esterases.

The molecular weight of EstSHJ2 was approximately 26 kDa, which was roughly equal to rEstSL3 from Alkalibacterium (Wang et al. 2016a, b), EstA from Enterobacter cloaca (Ke et al. 2018) and Est10 from Psychrobacter pacificensis (Wu et al. 2013a, b), however were smaller than most reported salt-tolerant esterases.

The newly characterized EstSHJ2 remained active at a wide range of NaCl concentrations and highest level of activity was noticed at 2.5 M NaCl concentration. EstSHJ2 was active with high concentration of NaCl (5 M) and without NaCl, indicating its halotolerant over halophilic nature. The salt tolerance of EstSHJ2 was stronger than many previously reported salt-tolerant esterases, however, the performance was lower than Est9X (Fang et al. 2014), Est700 (Zhang et al. 2018) and Est11 (Wu et al. 2015) which retained 80% higher activity at 5 M NaCl.

EstSHJ2 activity increased with increasing of salt concentration, which can be attributed to salt promotion of hydrophobic interaction between the enzyme and substrate (De Santi et al. 2015). It was known that halophilic enzymes contain multiple acidic amino acid residues to protect protein surface from dehydration (Müller-Santos et al. 2009; Fukuchi et al. 2003). The EstSHJ2 showed conserved acidic amino acid residues (9 Asp + 13 Glu), which may explain its high salt tolerance.

It was worth noting that the optimum temperature and pH of EstSHJ2 varied with the change of NaCl concentration, with the maximum optimum temperature and pH at 2.5 M NaCl concentration. Nevertheless, EstSHJ2 could achieve similar levels of activity at different optimum temperatures and pH.

EstSHJ2 remained 82% activity at 80 ℃ treatment for 2 h. Thermostability of EstSHJ2 was stronger than many thermophilic and halotolerant esterase such as GmDE (Smichiet al. 2015), E69 (Huo et al. 2017), EstA (Ke et al. 2018), est-OKK (Yang et al. 2014) and LKE-028 esterase (Kumar et al. 2012), but weaker than LipJ2 (Castilla et al. 2017) which retained activity after 100 ℃ incubation. The remarkable thermostability of EstSHJ2 may be related to two factors. Firstly, the small molecular weight of enzyme, due to compact protein natures may confer a higher thermostability than the bulky proteins (Lee et al. 1999). Secondly, high levels of proline (7.5%) and glutamate (6.1%) may be responsible for thermo stability (Manco et al. 1998). These factors may be the result of the long-term evolution of enzymes in the salt well which was 1,000 m underground with high temperatures.

Previous studies have reported that salt can increase thermo stability of halophilic esterase as we observed in our study (Rao et al. 2009; Camacho et al. 2010). The EstSHJ2 showed the best thermo stability at 2.5 M NaCl concentration. Additionally, salt also promoted the pH stability of EstSHJ2. Generally, high salinity conditions lead to high pH values, and the enzymes of halophiles tend to exhibit higher activity under alkaline conditions (Salihu et al. 2015). This justifies the rationale for the EstSHJ2-exhibited best stability upon alkali treatment (pH 11) at 2.5 M NaCl concentration. However, NaCl concentration had no effect on the activity of enzyme treated with acid (pH 4).

Nevertheless, the promotion of enzyme stability by salt was concentration dependent. The EstSHJ2 became less active at higher temperatures and pH levels, and this negative effect was reinforced by the presence of higher salts concentration of 4.5 M. The negative effect of high concentration salt may be due to the screening by salts of charge-charge interactions in protein (Perez-Jimenez et al. 2004).

Most of the previous studies have discussed separately the effect of temperature, pH and salt concentration on esterase activity. However, only limited studies have investigated the relationship between NaCl concentration and thermostability (Zhang et al. 2018; Rao et al. 2009; Camacho et al. 2010). Our study was the first to determine the effects of salt concentration on optimal temperature, pH and stability of halotolerant esterase. Therefore, in the industrial application of esterase, the reaction temperature and pH should be optimized according to the salt concentration. The salt increased thermostability of halotolerant esterase, however, only to a limited extent. Heat treatment of enzyme should be performed at a certain salinity to retain as much activity as possible, and enzymatic reaction should be carried out under alkaline rather than acid conditions, which was conducive to improve efficiency and save energy.

It was observed that low concentrations of metal ions did not have negative impact EstSHJ2 activities. The K+, Ca2+ and Mg2+ have greatly increased activity, which has also been reported in other salt-tolerant esterases such as H9Est (De Santi et al. 2015), rEstSL3 (Wang et al. 2016a, b), DHAB (Ferrer et al. 2005) and LKE-028 (Kumar et al. 2012). The reason for Ca2+ to increase esterase activity may be that it binded the C-terminal motif GXXGXD of enzyme and the formation of fatty acids at the oil–water interface (Rashid et al. 2001). The well salt from Zigong is rich in K+, Ca2+ and Mg2+, as well as other trace ions, which may explain the positive effect of these ions on EstSHJ2. However, opposite results have also been reported, such as the inhibition of K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Mn2+, Zn2+ and Ba2+ on PE8 (Wei et al. 2013), Est12 (Wu et al. 2013a, b), EstLiu (Rahman et al. 2016) and H8 (Zhang et al. 2017). On the other hand, the inhibition of Cu2+, Fe2+, Al3+ and Ni2+ on EstSHJ2 was also observed in other esterase such as WDEst17 (Wang et al. 2017), Est9X (Fang et al. 2014), PE8 (Wei et al. 2013) and H8 (Zhang et al. 2017). However, these ions showed activation effect on EstWSD (Wang et al. 2013) and est-okk (Yang et al. 2018). Therefore, effect of the same metal ions on esterase was uncertain, which may be related to the source of esterase and require future investigations.

High-salt environments often lead to low water activity, Therefore, the salt-tolerant enzymes have also organic solvents-tolerant. It is generally believed that polar solvents have a negative effect on enzyme activity because they are easier to strip water molecules from surface of enzyme than non-polar solvents (Doukyu et al. 2010). In this study, activity of EstSHJ2 in non-polar solvents was higher than that in polar solvents. Especially hexane, benzene and toluene promoted enzyme activity significantly. This activation effect, also found in other solvent-tolerant esterases such as RBest1 (Berlemont et al. 2013), Est700 (Zhang et al. 2018) and EstWSD (Wang et al. 2013), could be attributed to the interaction between organic solvent molecule and hydrophobic amino acid residues at the catalysis site of esterase, which made an open conformation of enzyme for catalysis (Rúa et al. 1993; Zaccai 2013). Furthermore, the EstSHJ2 exhibited a good tolerance to several polar solvents, and still maintained more than 40% activity in 30% methanol, ethanol and acetonitrile, which was stronger than some salt-tolerant esterases including ThaEst2349 (Jiang et al. 2012), E69 (Huo et al. 2017), Salimicrobium esterase (Xin et al. 2013) and Bacillus cereus esterase (Ghati et al. 2015). The use of organic solvent systems for enzymatic reactions had many advantages, including enhancing the solubility of non-polar substrates, inhibiting water-dependent side reactions, and eliminating microbial contamination (Doukyu et al. 2010). Owing to its strong organic solvents-tolerant, the EstSHJ2 may have great potential in organic synthesis and modification of fats and oil.

Non-ionic surfactants such as Triton X-100 tween-20 and tween-80 increased activity of EstSHJ2, while ionic surfactants such as SDS and CTAB have reduced activity. This result was similar to those of Est12 (Wu et al. 2013a, b), Est11 (Wu et al. 2015) and EstKT4 (Jeon et al. 2011), but the opposite results were found in PE10 (Jiang et al. 2012), est-OKK (Yang et al. 2018), rEstSL3 (Wang et al. 2016a, b) and Est9X (Fang et al. 2014). The effect of surfactants on esterases may be related to the origin and structure of enzymes. The PMSF inactivated EstSHJ2, indicating that the enzyme was a serine hydrolase as other lipases and esterases. Since no effect of EDTA on EstSHJ2 was noticed, enzyme was not metalloenzyme and was consistent with the fact that esterases were cofactor independent (Joseph et al. 2008). The inhibitory effects of DTT and β-mercaptoethanol indicated that disulfide bonds played important role in maintaining structure and activity of the enzyme, which could be explained by more cysteine in structure of EstSHJ2.

Esterases with a variety of properties are desirable. So far, there have been few reports about novel esterases with thermotolerant, halotolerant and organic solvent-tolerant properties, and information about esterase from Chromohalobacter sp. remained scarce. This study highlighted the optimum temperature, pH and stability of halotolerant esterase at different salt levels. The finding on EstSHJ2 activity demonstrated strong tolerance to NaCl, temperature and organic solvents. These properties suggested that EstSHJ2 had considerable potential for academic and industrial applications. Moreover, we propose that salt wells or mines offer great resources in exploring novel and valuable industrial enzymes.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Liquor Making Biological Technology and Application of Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province (NJ2018-07).

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. MW, LA, MPZ, and CW conceived and designed the experiments. MW, LA and MPZ performed the experiments and analyzed the data. MW, CW wrote the manuscript. CW and FQW critically revised manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Mou Wang, Email: xxw312558202@163.com.

Li Ai, Email: Aily0415@163.com.

Mengping Zhang, Email: zmp201413@163.com.

Fengqing Wang, Email: 254238766@qq.com.

Chuan Wang, Email: watpc57944@163.com.

References

- Aiyar A. The use of CLUSTAL W and CLUSTAL X for multiple sequence alignment. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;132:221–241. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akoh CC, Lee GC, Liaw YC, Huang TH, Shaw JF. GDSL family of serine esterases/lipases. Prog Lipid Res. 2004;43:534–552. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arpigny JL, Jaeger KE. Bacterial lipolytic enzymes: classification and properties. Biochem J. 1999;343:177–183. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3430177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barone R, De Santi C, Palma Esposito F, Tedesco P, Galati F, Visone M. Marine metagenomics, a valuable tool for enzymes and bioactive compounds discovery. Front Mar Sci. 2014;1:1–6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2014.00038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berlemont R, Spee O, Delsaute M, Lara Y, Schuldes J, Simon C, Power P, Daniel R, Galleni M. Novel organic solvent-tolerant esterase isolated by metagenomics: insights into the lipase/esterase classifcation. Rev Argent Microbiol. 2013;45:3–12. doi: 10.2147/0TT.S44474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornscheuer UT. Microbial carboxyl esterases: classification, properties and application in biocatalysis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2002;26:73–81. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(01)00075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho RM, Mateos JC, González-Reynoso O, Prado LA, Córdova J. Production and characterization of esterase and lipase from Haloarcula marismortui. J Ind Microbiol Biot. 2009;36:901–909. doi: 10.1007/s10295-009-0568-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho RM, Mateos-Díaz JC, Diaz-Montaño DM, González-Reynoso O, Córdova J. Carboxyl ester hydrolases production and growth of a halophilic archaeon, Halobacterium sp. NRC-1. Extremophiles. 2010;14:99–106. doi: 10.1007/s00792-009-0291-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castilla A, Panizza P, Rodríguez D, Bonino L, Díaz P, Irazoqui G, Giordano SR. A novel thermophilic and halophilic esterase from Janibacter sp. R02, the first member of a new lipase family (Family XVII) Enzyme Microb Tech. 2017;98:86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2016.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan M, Garlapati VK. Production and characterization of a halo-, solvent-, thermo-tolerant alkaline lipase by Staphylococcus arlettae JPBW-1, isolated from rock salt mine. Appl Biochem Biotech. 2013;171:1429–1443. doi: 10.1007/s12010-013-0433-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalmaso G, Ferreira D, Vermelho A. Marine extremophiles: a source of hydrolases for biotechnological applications. Mar Drugs. 2015;13:1925–1965. doi: 10.3390/md13041925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Santi C, Ambrosino L, Tedesco P, de Pascale D. Identification and characterization of a novel salt-tolerant ssterase from a Tibetan glacier metagenomic library. Biotechnol Progr. 2015;31:890–899. doi: 10.1002/btpr.2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Santi C, Leiros H-KS, Di Scala A, de Pascale D, Altermark B, Willassen N-P. Biochemical characterization and structural analysis of a new cold-active and salt-tolerant esterase from the marine bacterium Thalassospira sp. Extremophiles. 2016;20:323–336. doi: 10.1007/s00792-016-0824-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doukyu N, Ogino H. Organic solvent-tolerant enzymes. Biochem Eng J. 2010;48:270–282. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2009.09.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Z, Li J, Wang Q, Fang W, Peng H, Zhang X, Xiao Y. A novel esterase from a marine metagenomic library exhibiting salt tolerance ability. J Microbiol Biotechn. 2014;24:771–780. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1311.11071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer M, Golyshina OV, Chernikova TN, Khachane AN, Martins dos Santos VAP, Yakimov MM, Timmis KN, Golyshin PN. Microbial enzymes mined from the Urania deep-sea hypersaline anoxic basin. Chem Biol. 2005;12:895–904. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forouhar F, Lew S, Seetharaman J, Shastry R, Kohan E, Maglaqui M, Mao L, Xiao R, Acton TB, Everett JK, Montelione GT, Tong L, Hunt JF (2012) Crystal structure of the esterase YqiA (YE3661) from Yersinia enterocolitica. Northeast Struct Genom Consortium Target YeR85. 10.2210/pdb4FLE/pdb

- Fukuchi S, Yoshimune K, Wakayama M, Moriguchi M, Nishikawa K. Unique amino acid composition of proteins in halophilic bacteria. J Mol Biol. 2003;327:347–357. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghati A, Paul G. Purification and characterization of a thermo-halophilic, alkali-stable and extremely benzene tolerant esterase from a thermo-halo tolerant Bacillus cereus strain AGP-03, isolated from “Bakreshwar” hot spring. India Process Biochem. 2015;50:771–781. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2015.01.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R, Gupta N, Rathi P. Bacterial lipases: an overview of production, purification and biochemical properties. Appl Microbiol Biot. 2004;64:763–781. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1568-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan F, Shah AA, Hameed A. Industrial applications of microbial lipases. Enzyme Microb Tech. 2006;39:235–251. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2005.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holmquist M. Alpha/Beta-hydrolase fold enzymes: structures, functions and mechanisms. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2000;1:209–235. doi: 10.2174/1389203003381405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo YY, Rong Z, Jian SL, Xu CD, Li J, Xu XW. A novel halotolerant thermoalkaliphilic esterase from marine bacterium Erythrobacter seohaensis SW-135. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1–11. doi: 10.1016/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon JH, Lee HS, Kim JT, Kim S-J, Choi SH, Kang SG, Lee JH. Identification of a new subfamily of salt-tolerant esterases from a metagenomic library of tidal flat sediment. Appl Microbiol Biot. 2011;93:623–631. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3433-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Huo Y, Cheng H, Zhang X, Zhu X, Wu M (2012) Cloning, expression and characterization of a halotolerant esterase from a marine bacterium Pelagibacterium halotolerans B2T. Extremophiles. 16: 427–435. 10.1016/j.molcatb.2013.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Joseph B, Ramteke PW, Thomas G. Cold active microbial lipases: some hot issues and recent developments. Biotechnol Adv. 2008;26:457–470. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor M, Gupta MN. Lipase promiscuity and its biochemical applications. Process Biochem. 2012;47:555–569. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2012.01.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly SA, Megaw J, Caswell J, Scott CJ, Allen CCR, Moody TS, Gilmore BF. Isolation and characterisation of a halotolerant ω-transaminase from a Triassic period salt mine and its application to biocatalysis. ChemistrySelect. 2017;2:9783–9791. doi: 10.1002/slct.201701642. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ke M, Ramesh B, Hang Y, Liu Z. Engineering and characterization of a novel low temperature active and thermo stable esterase from marine Enterobacter cloacae. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;118:304–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.05.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar L, Singh B, Adhikari DK, Mukherjee J, Ghosh D. A thermoalkaliphilic halotolerant esterase from Rhodococcus sp. LKE-028 (MTCC 5562): enzyme purification and characterization. Process Biochem. 2012;47:983–991. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2012.03.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D-W, Koh Y-S, Kim K-J, Kim B-C, Choi H-J, Kim D-S, Suhartono MT, Pyun Y-R. Isolation and characterization of a thermophilic lipase from Bacillus thermoleovorans ID-1. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;179:393–400. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1097(99)00440-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-López O, Cerdán ME, González Siso MI. New extremophilic lipases and esterases from metagenomics. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2014;15:445–455. doi: 10.2174/1389203715666140228153801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manco G, Adinolfi E, Pisani FM, Ottolina G, Carrea G, Rossi M. Overexpression and properties of a new thermophilic and thermostable esterase from Bacillus acidocaldarius with sequence similarity to hormone-sensitive lipase subfamily. Biochem J. 1998;332:203–212. doi: 10.1042/bj3320203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno ML, Márquez MC, García MT, Mellado E. Halophilic bacteria and archaea as producers of lipolytic enzymes. Biotechnol Extremo. 2016;1:375–397. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-13521-2_13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Santos M, de Souza EM, de Pedrosa F, O., Mitchell DA, Longhi S, Carrière F, Canaan S, Krieger N, First evidence for the salt-dependent folding and activity of an esterase from the halophilic archaea Haloarcula marismortui. BBA-Mol Cell Biol L. 2009;1791:719–729. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozcan B, Ozyilmaz G, Cihan A, Cokmus C, Caliskan M. Phylogenetic analysis and characterization of lipolytic activity of halophilic archaeal isolates. Microbiology. 2012;81:186–194. doi: 10.1134/S0026261712020105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Jimenez R, Godoy-Ruiz R, Ibarra-Molero B, Sanchez-Ruiz JM. The efficiency of different salts to screen charge interactions in proteins: a Hofmeister effect? Biophy J. 2004;86:2414–2429. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74298-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao L, Zhao X, Pan F, Li Y, Xue Y, Ma Y, Lu JR. Solution behavior and activity of a halophilic esterase under high salt concentration. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6980. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman MA, Culsum U, Tang W, Zhang SW, Wu G, Liu Z. Characterization of a novel cold active and salt tolerant esterase from Zunongwangia profunda. Enzyme Microb Tech. 2016;85:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2015.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid N, Shimada Y, Ezaki S, Atomi H. Low-temperature lipase from psychrotrophic Pseudomonas sp. strain kb700a. Appl Environ Microb. 2001;67:4064–4069. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rúa ML, Díaz-Mauriño T, Fernández VM, Otero C, Ballesteros A. Purification and characterization of two distinct lipases from Candida cylindracea. BBA-Gen Subjects. 1993;1156:181–189. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(93)90134-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salihu A, Alam MZ. Solvent tolerant lipases: a review. Process Biochem. 2015;50:86–96. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2014.10.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sana B, Ghosh D, Saha M, Mukherjee J. Purification and characterization of an extremely dimethylsulfoxide tolerant esterase from a salt-tolerant Bacillus species isolated from the marine environment of the Sundarbans. Process Biochem. 2007;42:1571–1578. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2007.05.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schreck SD, Grunden AM (2014) Biotechnological applications of halophilic lipases and thioesterases. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 98: 1011–1021. 10.1007/s00253-013-5417-5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Smichi N, Fendri A, Gargouri Y, Miled N. A high salt-tolerant thermoactive esterase from golden grey mullet: purification, characterization and kinetic properties. J Food Biochem. 2015;39:289–299. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.12129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Wang Q, Lin X, Bun Ng T, Yan R, Lin J, Ye X. A novel cold-adapted and highly salt-tolerant esterase from Alkalibacterium sp. SL3 from the sediment of a soda lake. Sci Rep. 2016;6:1–10. doi: 10.1038/srep19494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Wang K, Li L, Liu Y. Isolation and characterization of a novel organic solvent-tolerant and halotolerant esterase from a soil metagenomic library. J Mol Catal B- Enzym. 2013;95:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.molcatb.2013.05.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Xu Y, Zhang Y, Sun A, Hu Y (2018) Functional characterization of salt-tolerant microbial esterase WDEst17 and its use in the generation of optically pure ethyl (R)-3-hydroxybutyrate. Chirality. 30: 769–776. 10.1002/chir.22847 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Zhang Y, Sun A, Hu Y. Characterization of a novel marine microbial esterase and its use to make D-methyl lactate. Chin J Catal. 2016;37:1396–1402. doi: 10.1016/S1872-2067(16)62495-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X, Jiang X, Ye L, Yuan S, Chen Z, Wu M, Yu H. Cloning, expression and characterization of a new enantioselective esterase from a marine bacterium Pelagibacterium halotolerans B2T.J. Mol Catal B-Enzym. 2013;97:270–277. doi: 10.1016/j.molcatb.2013.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Wu G, Zhan T, Shao Z, Liu Z. Characterization of a cold-adapted and salt-tolerant esterase from a psychrotrophic bacterium Psychrobacter pacificensis. Extremophiles. 2013;17:809–819. doi: 10.1007/s00792-013-0562-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Zhang S, Zhang H, Zhang S, Liu Z. A novel esterase from a psychrotrophic bacterium Psychrobacter celer 3Pb1 showed cold-adaptation and salt-tolerance. J Mol Catal B-Enzym. 2013;98:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.molcatb.2013.10.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Zhang X, Wei L, Wu G, Kumar A, Mao T, Liu Z. A cold-adapted, solvent and salt tolerant esterase from marine bacterium Psychrobacter pacificensis. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015;81:180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin L, Hui-Ying Y (2013) Purification and characterization of an extracellular esterase with organic solvent tolerance from a halotolerant isolate, Salimicrobium sp. LY19. BMC Biotechnol. 13: 108. 10.1186/1472-6750-13-108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yang X, Wu L, Xu Y, Ke C, Hu F, Xiao X, Huang J (2018) Identification and characterization of a novel alkalistable and salt-tolerant esterase from the deep-sea hydrothermal vent of the East Pacific Rise. MicrobiologyOpen. e00601:1–10. 10.1002/mbo3.601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zaccai G. The effect of water on protein dynamics. Philos T R Soc B. 2004;359:1269–1275. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Xu H, Wu Y, Zeng J, Guo Z, Wang L, Shen C, Qiao D, Cao Y. A new cold-adapted, alkali-stable and highly salt-tolerant esterase from Bacillus licheniformis. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;111:1183–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.01.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Hao J, Zhang Y-Q, Chen X-L, Xie B-B, Shi M, Zhou B-C, Zhang Y-Z, Li P-Y. Identification and characterization of a novel salt-tolerant esterase from the deep-sea sediment of the South China Sea. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]