Abstract

Challenges are one of the most common strategies used by Opinion Leaders on Social Media to engage users. They are often found in different areas; in the Health field, the use of challenges is growing, namely through initiatives aiming at eating behaviour change. Instagram is considered to be one of the most used Social Media applications to develop these initiatives, allowing Opinion Leaders to communicate and engage with their online followers. Despite this scenario, little is known regarding how Health Challenges are being used and what is their impact on behaviour change. Previous research has already shown how Opinion Leaders use Instagram to promote eating behaviour change. The purpose of this paper is to conceptualize, describe and discuss Social Media Health Challenges, aiming to analyse Instagram challenges on healthy eating. The study was organized in two phases: the first one is a literature review based on Prisma method that supported the conceptualisation of Social Media Challenges and the design for the second phase where Social Media Health Challenges of Opinion Leaders, such as Nutritionists, Health Lifestylers and Patient Opinion Leaders (POLS) were analysed. Results showed that most of the challenges are promoted by Patient Opinion Leaders and Health Lifestylers. Followers adhere to Social Media Health Challenges related to weight loss, engaging with Opinion Leaders. The psychological-cognitive components (such as habits, motivation, and self-control) were found in the analysed challenges, and Instagram is one of the used tools to promote these Initiatives. These results point to new paths regarding future research on other behaviour change online initiatives.

Keywords: Behaviour change, Health eating challenges, Opinion leaders, Instagram, Social Media, eHealth

Introduction

Behaviour and its relation to stimuli is the Behaviour Science major focus. These stimuli are actions of environmental variants that reinforce, elicit and evoke behaviours. These variants are generic objects, people and their interrelationships that are observed and together are potential sources to develop the behavioural repertoire of an individual. Thus, the more observed objects and people, the more the behavioural repertoire (Smith, 2015).

The current digital scenario is adding complexity to the Behaviour Science field: digital technologies are creating objects that allow a massive number of people to communicate and get together in a new environment. These technologies are increasing the referred behavioural repertoire that should not be seen only on an individual level, through the reconfiguration of human behaviour, but also on a collective level modifying the society and the people relationships in a multitude of fields. One of these environmental variants are digital tools (mobile devices, wearable sensors, biomarker detectors, and real-time access to therapeutic support via information technology) that are already referred by Dallery, Kurti, & Erb (2015), as also online social networks that enable people to get in touch and assume a more active and participative role (O’Reilly, 2005).

These new networks allow recently discovered behaviours to occur in the most varied fields, including health. Back in 2013, 72% of Internet users looked up information on the experience of others with the same type of health problem, and 8% posted this type of content (Fox & Duggan, 2013). A new health care scenario is growing: appointments, treatments and the relationship between health professionals and patients are no longer dependent only on health services and most of these new interventions are being used to increase health care efficacy, based on scientific practices, giving rise to what is known as eHealth (Eysenbach, 2001).

In this context, the Behaviour Science perspective (referred above) can also bring an enriched view on the role that digital media can play when supporting health interventions. Understand, plan, influence and evaluate behavioural factors that were led by a specific stimulus (Bartholomew, Parcel, Kok, & Gottlieb, 2006) are of most importance when it comes to support health interventions aiming to behaviour change, namely the ones focused on weight loss, based on promoting healthy behaviour, through dietary factors and physical exercise. Excessive weight, and specifically obesity, comes from behaviour that is not health orientated, with large calories intake and little calories expenditure (Freedman, 2016). Consequently, the Behaviour Science perspective could have a crucial impact in addressing obesity, considered the epidemic of the XXI century (World Health Organization, 2016), considered to be one of the risk factors contributing towards 86% of all deaths in the world (World Health Organization, 2018). Dallery, Kurti, & Erb (2015) refer that traditional health interventions could, therefore, benefit from the complementary approach brought by digital tools which currently play a significant role in this domain, affecting behaviour factors (motivation and stimulus), health behaviour and its consequences.

In the Health sector, the interventions that are mostly influenced by digital tools is those aimed at weight loss (Dallery, Kurti, & Erb, 2015). It is therefore worth observing the healthy practices of online social networks users related to food and physical exercise (Chung et al., 2017; Helm & Jones, 2016; Leggatt-Cook & Chamberlain, 2012). Online social networks have increasingly gained importance nowadays, namely Instagram in which there are numerous profiles, such as those of Opinion Leaders (Nutritionists, Healthy Lifestylers and POLs), that group together a large number of followers (Saboia, Pisco Almeida, Sousa, & Pernencar, 2018). Topics such as types of diets, nutritional components, and healthy recipes have found a space of communication. Emotional support is also a topic observed like motivation, trauma from being obese and behavioural change (Saboia et al., 2018). There is also what is called the rising of a culture of nutritional science transmitted by the media (Dodds & Chamberlain, 2017).

One of these practices, already referred to in the study Saboia et al. (2018), is the Social Media Health Challenges. This study indicates that Social Media Health Challenges are common strategies used by Opinion Leaders (Nutritionists, Healthy Lifestylers and POLs) to communicate and engage with their followers. These challenges are used to help reduce weight, through general healthy behaviour guidelines for eating and working out, they can be suitable to many people and different situations: the removal of sugar or alcoholic beverages from a diet, or working out for one hour per day or 8 sleep hours. These proposals are defined, assembled, planned, implemented and promoted by the Opinion Leaders, and for the purposes of this study done through Instagram. It should be accepted and done by followers, with a date scheduled for its beginning and end. Based on this study, the research team considered this type of challenge as a new tool for communication and engagement with an online audience. They thought it over and concluded this initiative could have potential to behaviour change. A literature review about this subject was undertaken, and the researchers drew a conclusion that this was not clear enough. Because of these points and the theme relevance, the research team agreed that this phenomenon was important, and it needed to be a topic to study.

This current study aims to conceptualize and describe Social Media Health Challenges and others, analysing Challenges focused on Healthy Lifestyles topics, such as eating healthy food. This research seeks to deepen knowledge on these practices, supported by a behaviour analysis perspective aiming to understand the theoretical framework related works and user profiles about how they create and promote the practice of Social Media Health Challenges launched via online social networks. These practices are observed through a health intervention perspective, based on behaviour-oriented theories from Bartholomew et al. (2006). A literature review was undertaken, revealing how little is known regarding how Social Media Health Challenges are being used and its impact on behaviour change, and four key aspects related to these challenges were studied: objectives, method, participation and duration.

Structure of the Study and the Main Methodologies

The starting point to understand this theme was to identify the foundations and dynamics that support Social Media Challenges. Thus, this study follows two main phases. The first phase of the study was mainly dedicated to the preliminary studies where a narrative literature review was carried out on section 2: 2.1 Social Media Challenges; 2.2 Digital behaviour change interventions; and both to the behaviour-oriented theories used in health promotion (2.2.1) and to health intervention focused on feeding behaviour (2.3). For the authors of this paper, two of the most highlighted results of this phase were to understand how to, scientifically, conceptualize the Social Media Challenges and how to elaborate a diagram model of Social Media Challenges transmission (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Social Media Challenge transmission (challenger x challenged)

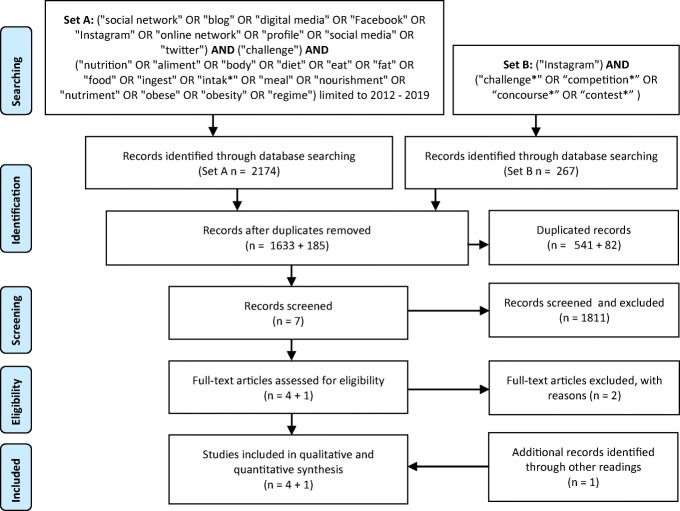

The second phase, which is presented in section 3, includes a literature review of the most important articles published by the scientific community related to Social Media Health Challenges. For this particular step, this study followed the Prisma model (Figure 2 – Section 3.1). The result of this review led to the concept (3.2.1) and to the description of a Social Media Health Challenge mechanism (3.2.2). The purpose of these outcomes served the creation of an analysis grid, which supported an observational analysis of Instagram Health Challenges.

Fig. 2.

Literature review diagram - PRISMA (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & Group, 2009)

The grid was used aiming to answer the following research question a) What are the main characteristics of a Social Media Health Challenge? In particular, the study aimed at understanding: How are these challenges created? What are their objectives? Who are the actors involved? What are the proposed change behaviours? How long do these challenges last? What are the hashtags being used? What are the topics discussed in the posts created by the challengers? What are the topics that the most popular posts present? What are the artefacts that were used? Are there neknomination, enrolment, payment or prizes? Which are the most found components (psychological-cognitive, food, exercises, habits or models)? All these questions are addressed in the Results section (4.1)

Preliminary Studies

Social Media Challenges

Social Media Challenges are common practices on online social networks, but few are described in the literature. For the purpose of framing this topic, three Social Media Challenges were selected, based on different studies already published and considering its social impact (Mahadevaiah and Nayak, 2018): “The Cinnamon Challenge”, “The Ice Bucket Challenge” and “The Blue Whale Challenge”.

“The Cinnamon Challenge” is a challenge that dates back to 2001 but reached its peak in 20121, with its dissemination through a YouTube video. This video shows a group of adolescents challenging each other2. This challenge consists of recording a person swallowing a spoon of ground cinnamon and not drinking any liquid for 60 seconds. Although this may seem simple, it is impossible and can be a health risk. This challenge is generally done by people between the ages of 13 to 24 with a need for social conformity (Grant-Alfieri, Schaechter, & Lipshultz, 2014). This challenge is only documented in one article founded in the Scopus database (Grant-Alfieri et al., 2014). The main emphasis of the challenge is that of overcoming an obstacle, to know who can complete an action that should happen during the video. Also, the behaviour is not prolonged, and as such does not require long term behavioural change. One of the tools used for identification, sharing and collection in this challenge is “#”, related to the message #cinnamonchallenge.

“The Ice Bucket Challenge” was a behavioural phenomenon that led to 17 million online videos that raised awareness of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), as well as helping raise funds for research of this disease (Burgess, Miller, & Moore, 2017; Chang, Yang, Lyu, & Chuang, 2016; Gualano et al., 2016; Kilgo, Lough, & Riedl, 2017). This challenge consists of two options: recording and posting a video on online social networks of the challenged pouring a bucket of ice over their own head, or donating money to a charity. As more adhered to the challenge, there were two changes: those challenged started to invite those closest to them to participate, and the challenge became associated with fundraising for the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Association. This challenge had a significant presence on social and more traditional media (Kilgo et al., 2017), as it had many world-famous people participating (Ni, Chan, Leung, Lau, & Pang, 2014). One of the critical factors in this challenge was the public invitation made when one challenged person nominated the next, Neknomination (Burgess et al., 2017), as a chain, fun or game (Gualano et al., 2016). The association of one person to another demonstrates proximity, generating pressure and social influence. Some researchers consider this action to be a kind of game, in which one friend calls another to participate (Gualano et al., 2016). This phenomenon brought much visibility to ALS and its respective research (Koohy & Koohy, 2014; Pressgrove, Mckeever, & Jang, 2018). This challenge used the following messages for online identification #icebucketchallenge #ALS #ALSIceBucketChallenge (Kilgo et al., 2017; Koohy & Koohy, 2014; Pressgrove et al., 2018).

It is interesting to note that there is research that designates this type of challenge (such as the Ice Bucket one) as a new category called Viral Challenge Memes (VCM). VCM's are considered to be a manifestation of digital culture, in which there is the need for social belonging through engagement did via two aspects: the execution of specific behaviour, and the invitation of someone close to do the same (Burgess et al., 2017). This type of challenge is part of a separate category because they have the following characteristics: there is a rational in participating, the behaviour is not totally outlandish, there is an emotional connection to the topic and the people involved in the challenge, the practices are connected to famous people, and the challenges are not distant (Burgess et al., 2017). Furthermore, the feeling of conformity evoked from challenges like “The Cinnamon Challenge” is not so clearly exposed. VCM's do not involve feelings of obligation but rather through feelings of innovation and being distinct (Burgess et al., 2017). There is a more significant emphasis on passing the challenge from one person to another and showing the ties that connect them than necessarily the behaviour involved. The behaviour has short-duration, and it did not require long-term behavioural change.

Understanding the way the scientific community has studied this Social Media Challenge is of relevance, and the keywords “ice bucket” AND “challenge” together in the Scopus database show 44 results, which are related to areas such as medicine, engineering, social science, computer science, among others. Generally, the topics in these studies are connected with two big groups. One related to research financing and public health actions, dissemination of knowledge of diseases and science connected to this knowledge (Gualano et al., 2016; Koohy & Koohy, 2014); the second group is related to the issue of how media is connected to health campaigns, the virality of the message and the motivation behind it being shared (Burgess et al., 2017; Chang et al., 2016; Kilgo et al., 2017; Ni et al., 2014; Pressgrove et al., 2018).

“The Blue Whale Challenge” is a contradictory challenge, not only because of the origins but also its dynamics and objectives (Das & Gowda, 2018). This challenge was analysed because of its significant media presence, despite having relatively little medical repercussions (Balhara, Bhargava, Pakhre, & Bhati, 2018; Curti, Di Vella, Racalbuto, Coppo, & Lupariello, 2018; Mahadevaiah & Nayak, 2018). This challenge is considered to be a suicide game where actions from a list were carried out. The tasks involved are to be completed daily and over 50 days (Mahadevaiah & Nayak, 2018). Some of these should be recorded and sent to the challenger, also known as the “curator” in this challenge. The contact with others that were challenged, whales, and with the curator via video, photos and teleconferencing is also promoted, as well as competition between them (Curti et al., 2018; Mukhra, Baryah, Krishan, & Kanchan, 2017). Each individual task is considered a challenge, and for each task behaviour to be imitated is encouraged (Sumner et al., 2019). As the overall challenge and time progress, each task becomes increasingly harder and riskier, leading to behaviour change that is meant as preparation for the final moment. The objective of the challenge is to complete all tasks, with the last being that of taking one's life, “cybersuicide” (Narayan, Das, Das, & Bhandari, 2019; Sumner et al., 2019). The target audience is vulnerable teenagers (Khan, Moin, Fatima, Hussain, & Qadir, 2018).

According to Mukhra et al. (2017), the dynamics of this challenge involves the following scenario: a curator finds, via Social Media, a profile susceptible to this type of game, makes an invitation via a secret link shared on online social network chats, and accompanies and motivates those challenged to complete the tasks. An valuable tool to spread the challenge is the use of “#” with messages like #i_am_whale or “I’m ready to do it #bluewhalechallenge”. The Scopus search that included the strings “blue whale” and “challenge” led to 22 documents. These documents can be essentially split into 3 groups: medical reports on patients that allegedly participated in this challenge, the risk attributed to this phenomenon, and how the challenge was disseminated online.

These Social Media Challenges can go from just being a bit of harmless fun to leading to bodily harm or even death. As such, according to Mahadevaiah & Nayak (2018) one of the ways they can be categorised is how dangerous they are: (a) harmless challenges, those which do not involve any bodily harm, and are more likely to be either silly or fun and some cases even somewhat helpful (examples of which are mannequin challenge and bottle-flipping challenge); and (b) harmful challenges, which can involve bodily harm and may even lead to death (examples of these being the salt and ice challenge, “The Cinnamon Challenge”, and the choking game).

This analysis of the literature related the challenges that were discussed, revealed some common dimensions on Social Media Challenges and allowed the proposal of a model, presented bellow (Fig. 01): they are a behavioural phenomenon, launched by a challenger through the requirement of performing a given task, and in some cases, those challenged also challenge others to follow them Neknomination (Burgess et al., 2017). Participants, challenger and those challenged, form a kind of alliance, with the intention of promoting continuity by spreading the challenge to other people. A challenged participant can become a challenger by executing, recording and posting the challenge online. The invitation to participate is consensual; however, it is not free from influence to do ties that exist due to factors such as proximity or fame. These Social Media Challenges have a robust technological base, as they are done via the Internet and more specifically on online social networks, with video and photos being the most common support formats. All Social Media Challenges seek to be disseminated and in some cases can be considered to go viral. To take a challenge means to accept, execute a behaviour, record it digitally and post it on Social Media. Furthermore, some stages are analogical or digital and can be of shorter or longer duration, depending on the nature of the Social Media Challenge. Every time a challenge is ‘taken’, this practice can be updated, and a new characteristic added, and due to this communication, there is space for innovation and fun, allowing gamification (Koster, 2014) to appear in some cases. It means that a challenged person can also end up co-creating, effectively becoming a co-creator.

Besides the participants, the digital tools used to create and transmit the challenges are also crucial for this analysis. Due to the technological capacities and the way they contribute towards the success of these practices, the devices and the main features of mobile applications cannot be ignored. For instance, the tool # together with the message are used to identify content and aggregate participants, what can promote and disseminate the challenge practice.

Figure 1 and Table 1 systematize this analysis allowing a more clear view on how Social Media Challenges are transmitted and chained, as well as illustrating the main differences between the 3 challenges presented above, “The Cinnamon Challenge” (Grant-Alfieri et al., 2014), “The Ice Bucket Challenge” (Burgess et al., 2017) and “The Blue Whale Challenge” (Mukhra et al., 2017) , enabling posterior comparison to the Social Media Health Challenges.

Table 1.

Differences between the Cinnamon, Ice Bucket and Blue Whale challenge

| Challenge | Cinnamon | Ice bucket | Blue Whale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Implicit question | Can they handle it? | To who will it be passed on to? | Do they have the courage to execute? |

| Support artefact | Video | Video | Photos, videos, teleconferences |

| Deadline | Enough to film the video | Enough to film the video | Daily tasks during 50 days |

| Behavioural change | No | No | Yes |

| Categories | Harmful challenge e Overcome | Viral Challenge Meme | Harmful challenge e Overcome |

| Target audience | 13 to 24 year olds | Famous people | Adolescents |

| Hashtag use | #cinnamonchallenge | #icebucketchallenge #ALS #ALSIceBucketChallenge | #i_am_whale #I’m ready to do it #bluewhalechallenge” |

Given these 3 different challenges and their respective modalities, it is necessary to find out how Social Media Health Challenges can fit in, as they do not have an emphasis on transmission like in the VCMs or risk of bodily harm like in the harmful challenges (Blue Whale). Social Media Health Challenges are, most of the times, considering harmless challenges, being necessary to better understand how could they be categorized in such a model. According to Saboia et al. (2018), these Social Media Health Challenges are not related to one-off behaviour but rather to a routine of healthy eating and physical exercise done over a stipulated period. Being of a more extended period, they can lead to behaviour change, which is usually not possible to observe during the short filming of the videos that integrated the above-described challenges. Social Media Health Challenges are usually proposed by people with scientific knowledge of the area such as Nutritionists, or those who are closely connected to the health domain, like POLs and Health Lifestylers.

When healthy behaviour is promoted online, it is essential to study the digital behaviour change interventions, namely the behaviour-oriented theories used in health promotion and the eating behaviour that are discussed in the following sections.

Digital Behaviour Change Interventions

As described above, Social Media Health Challenges are different from other Social Media Challenges, as they seek long term behaviour change and promote healthier behaviour via healthier eating. The digital behaviour change interventions theory seems appropriate to frame this phenomenon (Sillence, Little, & Joinson, 2017). These interventions focus on the changes that are achieved using digital media, for delivery, recording and data collection, as well as to improve the environment in which they occur and to promote the desired behavioural patterns. Digital technology has a fundamental role and should be considered beforehand when behaviour change requirements are being selected: it should be discussed and analysed not only to adapt the intervention, but to decide when and why it should be used. Digital behaviour change interventions call, therefore, for an interdisciplinary approach involving various fields like psychology (especially behavioural), sociology, design and software engineering (Sillence et al., 2017).

Despite this interdisciplinary view, behaviour change interventions are part of an already consolidated field of study (Bartholomew et al., 2006; Glanz, Rimmer, & Viswanath, 2008; Little, Sillence, & Joinson, 2017) integrating all behavioural and social theories to the practices of planning, implementation and evaluation of health interventions. As such, all of this theoretical framework should be taken into account when evaluating Social Media Health Challenges. Bartholomew et al. (2006) state that one of the most relevant aspects to create a successful intervention is to have it based on both theory and practice. Health interventions should also follow a systematic approach in terms of their development, time investment, resources and effort. This systemization occurs from the very beginning, via a planning intervention design aspect commonly called intervention mapping. This mapping consists of an ordered task list that works as a basic steps guide. One of the most crucial points of this map is integration of the theoretical and practical aspects (Step 3), connecting the objectives (Step 2) to the 'assembly' of the intervention (Step 4) by establishing methods and practices that have a proven track record. This map should have the following stages: 1 - Needs Assessment; 2 - Matrices of Change Objectives; 3 - Theory-Based Methods and Practical Strategies; 4 - Program; 5 - Adoption and Implementation; 6 - Evaluation Planning (Bartholomew et al., 2006). In this context, the study described in this paper is based on both theory and evidence and aims to discuss the theories, methods, and strategies that are used, not only by other researchers but also by Instagram Opinion Leaders (Nutritionists, Healthy Lifestylers and POLs) that influence healthy eating behaviour.

Behaviour-oriented Theories used in Health Promotion

The field of psychology and sociology has developed a considerable range of theory that is used in health interventions. Those will affect the selection of intervention groups, desirable behaviour, favourable environmental conditions, methods and techniques. Back in 2008, a total of 137 behaviour change techniques used in interventions were found in a literature review (Michie, Johnston, Francis, Hardeman, & Eccles, 2008). As such, those associated to health challenges as described by Saboia et al. (2018) will be considered as Goal-setting Theories (GST), Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) and Diffusion of Innovation Theory (DIT) (Bartholomew et al., 2006). As such, based on Bartholomew et al. (2006), the research team discussed and associated health challenges (Saboia et al., 2018) to Goal-setting Theories (GST), Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) and Diffusion of Innovation Theory (DIT) (Bartholomew et al., 2006). These theories are described below to understand the context of the present study.

When dealing with health-related behaviour, treatment is based on behaviour change theory, which can be on an individual and environmental level (Bartholomew et al., 2006). Both individual and environmental approaches can be appropriate and depend on the guidance given by the professional. On an individual level, there is a focus on avoiding risk behaviour; whilst on an environmental level, there is a focus on environmental conditions (Bartholomew et al., 2006). In the field of behaviour analysis, there is a more significant amount of studies focused on the latter, where special attention is given to obesogenic environments (Lake & Townshend, 2006): those that have conditions enabling obesity and try to control those conditions, support good choices and go against bad ones (Sigurdsson, 2014). The environmental focus is not only on physical environments but can also be present in digital environments, such as e-commerce sites, search engines, websites, Internet databases and Social Media, which have had an increasing effect on user behaviour (Sigurdsson, Menon, & Fagerstrøm, 2017). Therefore, there are interventions that can positively affect digital environments, such as online social networks, creating favourable environments that can support behavioural change and lead to users having healthier behaviour.

As stated by Bartholomew et al. (2006), the idea of a challenge is one of the fundamental principles in the definition of objectives of the goal-setting theory, came from Locke work (1968). This work is based on the goal-setting method. The author states that people feel motivated when clear objectives are defined, and they receive appropriate feedback. The study declares that there is a big relationship between cause and effect, goal setting and desired behaviour. With this method, the health interventionists try to help goal setting by suggesting strategies so that there may be behavioural change and consequently results. The justification for this is that people with defined choices are more easily directed to that which interests them, make more considerable efforts and resist setbacks better (Latham & Budworth, 2007). As such, the simple act of goal-setting can lead people to try to establish goals that are according to their knowledge and skills, using their previous experience and applying it to new situations (Locke & Latham, 2002). This means that it is essential to reflect on the objectives and strategies established in health challenge interventions, taking advantage of the participant knowledge, skills and experience to achieve better results.

The use of a challenge is a fundamental principle for defining objectives. It means that these objectives should have different levels of challenges, which depend on the individual's skills and efficacy, effort and subsequent reward. In other words, when users have a proposed goal, they evaluate their experience, capacity to execute a specific behaviour, the action that needs to be done and the reward they expect to receive once they do it. Goal setting should be well balanced in terms of its level of difficulty; it should not be too easy otherwise it will be seen as being of little importance and will give no real satisfaction on task accomplishment, but it also shouldn't be too difficult in that people feel that the task is unachievable. The reward should also be adjusted in accordance with the effort required to execute a task, meaning that the reward should improve as tasks become harder. This balance should be challenging, but realistically doable. The conquest of an objective should not only be associated with the objective itself but also to the satisfaction arises from achieving it (Locke & Latham, 1990).

According to the GST, for objectives to be motivating, they should take into consideration 5 principles: Challenge (referred to above), Clarity, Commitment, Feedback and Task Complexity (Locke & Latham, 1990). Clarity, as objectives, should be clear and measurable. Commitment is needed, because objectives should be considered to be a commitment from all involved (it is easier for people to make an effort in challenges that they deem realistic and agree with). According to Task Complexity, more complex tasks can be divided into subtasks according to goals, with Feedback being provided. Depending on the situation, the performance of the task can be improved through encouragement and/or recognition. The goal method should facilitate success and not be restrictive, allowing enough time for the tasks to be realistically completed. As such, this method requires objectives to be clear, challenging and realistic according to the set time for its conclusion. Furthermore, all of the parts should be committed to providing Feedback whenever possible or necessary (Locke & Latham, 1990). Bartholomew et al. (2006) state that this method should be used with people that are highly motivated towards behavioural change and that behaviour generate clear Feedback. Intervention groups should be divided according to self-efficacy and skills.

Two other theories that can be used are SCT (Bandura, 1977) and DIT (Rogers, 2003). Both are complex theories that take into consideration behaviour, cognition, society and environment. The central premise of the SCT is that people acquire knowledge by observing the behaviour of others and subsequent consequences (reward or punishment). Therefore, learning does not occur via personal experience but also from experience accumulated by observing social interactions and media. This concept of learning is called Modelling, and it can influence individual's future behaviour. Modelling, which involves modifying behaviour through observation, is influenced by the attention and perception given to the important points of the model, through the capacity to remember, produce (according to the action) and the motivation that occurs by verification of the model to be rewarded or punished (Bandura, 1977). This observation creates social models, rules for behaviour and social norms. As such, Bandura (1977) also highlights the importance of what is beyond the individual level, i.e. the environment, as the sum of all external factors that can influence an individual's behaviour. The environment can be social due to being comprised of people (such as family) and can be physical, consisting of environmental conditions, food, etc. Bartholomew et al. (2006) claim that interventions based on SCT should promote active learning and that the execution of a task should be done through guided practice and the use of a model to be followed: reinforcing should be correspondent to the actions. The promoters should also present models that are conducive with a healthy lifestyle and use environmental conditions that enable positive behavioural change (Bartholomew et al., 2006).

Finally, and given that this study involves analysing Opinion Leaders, it is necessary to take into consideration the DIT, which integrates these actors within a framework that has the objective of spreading innovation (idea, practice or service). The key aspect of this theory comes from Rogers' work (2003) as it explains how people adopt, implement and keep being innovative. Rogers identified three different types of actors: (i) the adopters, which adopt the technology; (ii) the change agents, in charge of promoting adoption and who are usually paid for this; and (iii) the Opinion Leaders who are capable of influencing other people's behaviour. Each individual goes through these 5 stages when adopting an innovation: knowledge, persuasion, decision (rejection or acceptance), implementation and confirmation. According to Bandura (1977) communication tools can be considered as a facilitator for adoption an innovation, because they allow and transmit social support, as well as provide behaviour model (Modelling). In the last case, a previous group of adopters can serve as behaviour models, just as an innovator adopter can serve as a model for an early adopter.

These three theories (GST, SCT, DIT) are an essential part of the approach to analysing Social Media Health Challenges, identifying methods, strategies, participants and mobilized components, related to eating behaviour.

Eating Behaviour and Health Interventions

Social Media Health Challenges are very much related to the execution of specific eating behaviour, not considered to be a specific action at a specific time but rather as representative behaviour as a whole. As such, eating behaviour is complex because it is the result of actions of deliberation, like reflection, decision and planning, as well as automatic factors, like instinctive actions, emotional connections to specific food and temptations (Rothman, Sheeran, & Wood, 2009). This type of behaviour should be contextualized through the coexistence of two systems, one reflexive and the other automatic (Table 2). The reflexive system has a quicker learning curve due to communication with others, conscious thought and the process of deliberation. On the other side, the automatic system has a slower learning curve due it being based on accumulated experience and the thought involved being automatic, and without any real deliberation.

Table 2.

Behaviour systems (Rothman et al., 2009)

|

Reflexive System: • Quick learning curve. • Language and dialogue based • Based on conscious thought. • There is deliberation and intentionality. |

Automatic System: • Slow learning curve. • Based on accumulated experience • Automatic thought and not conscious. • There is no deliberation or intentionality |

Each eating experience is accumulated over time, creating attitudes and eating habits (Rothman et al., 2009). As eating behaviour is an essential behaviour for survival, it occurs repetitively and routinely. In this aspect, there is strength in the creation of attitudes and habits. Attitudes are the first conscious or unconscious impressions formed from being exposed to a specific stimulus. These attitudes categorize the stimulus and evaluate them as positive and negative. As such, these automatic reactions are selective in terms of attention and perception, and can condition future behaviour. Habits are deep-rooted behaviours that are part of the automatic system, function without reflection and are capable of predicting intentions and future behaviour.

An experience that is repeated has cumulative value, which formats deep processes that are part of the automatic system and can create attitudes and habits that are difficult to change (Bartholomew et al., 2006; Rothman et al., 2009). Furthermore, each time a person comes into contact with food and/or has a meal; this experience is associated with specific environmental context and stimulus. This means that context and stimulus are capable of affecting attitudes and habits (Bartholomew et al., 2006; Rothman et al., 2009).

Consequently, a health intervention that seeks to change eating behaviour should try to consciously and unconsciously influence its target audience by changing not only behaviours but also attitudes and habits. On an initial level and in the short term, it may help an individual to consciously expect a result, reflect on the effort required to change, make a decision, plan strategies, help maintain a course of action, and act so as to achieve their objective. On another deeper level, and so that change is effective and long term, it is necessary that behaviour is repeated for long enough to become a habit. It is this aspect that contributes towards the medium and long-term success of many interventions. As such, the issue of Time should be analysed. It is important to highlight that research in psychology (Bargh & Chartrand, 1999), and health promotion interventions approaches commonly contemplate a conscious subject which interprets the world systematically and plans their actions (Bartholomew et al., 2006), whilst frequently forgetting many of the more automatic aspects.

Literature Review

As previously described, Social Media Health Challenges are directed towards healthy eating and can be categorized according to their actors (Opinion Leaders – Nutritionists, Healthy Lifestylers and POLs), following some common dynamics (like for example the definition of objectives and challenge acceptance). This study aims to increase the knowledge of the Social Media Health Challenge practice, and for this purpose aims to understand what are Social Media Health Challenges, why are they conducted, how do Social Media Health Challenges occur, which actors are involved, and how long does a challenge on average last.

After establishing these objectives, a literature review was done using two different databases, Scopus and Web of Science. Two different word orders were applied (Figure 2). The initial order used the following strings: "Instagram" AND "challenge *", which led to 267 results, with 82 being duplicates in both databases. The title and abstract of the remaining records (185) were analysed, and in case of any doubts, the word "challenge" was searched for within the text and the respective section was analysed. Only one work met the inclusion criteria (Chung et al., 2017) and led to a second one (Epstein, Cordeiro, Fogarty, Hsieh, & Munson, 2016). This quantity (2 papers) was considered too small and, therefore, the search was maintained, but it was extended to include keywords related to: "social network" AND "challenge" AND "nutrition". 2174 results were generated, with 541 of these being duplicated. The title and abstract of the records were analysed, and the procedure described above was followed. From this second phase, another 4 studies were identified and chosen based on following inclusion criteria: it should be about challenge, such as well as a competition that aiming eating behaviour; and exclusion criteria: all initiatives that are not associated behaviour change. It led to a total of 6 studies to be read and analysed.

Related Work

The first analysed work was Chung et al. (2017), describing a study developed in the USA, the only found during the first search with the strings Instagram and Challenge. It is the only study to mention Instagram and, despite not presenting an experimental and although it does not focus on the challenges, it intends to understand if Instagram is being used to accompany diet and exercise. People were recruited via the use of a questionnaire that was disseminated through researcher contact networks, using hashtags with the strings #fooddiary and #foodjournal. Recruiting was done using snowball sampling. All of the interviewees were rewarded with a gift card. 16 semi-structured interviews were conducted, and the conclusions show that people post images of their food on Instagram because they consider it to be easy, fun, motivating and they want to encourage others, as well as being useful to track their own eating habits. They share information and ideas to educate, give and receive emotional support. The users that participate in the challenges claim that have used hashtags to identify and get together, to know how each one are evolving and to exchange information on eating habits and exercise routines, forming communities that have a common challenge.

The second study (Epstein et al., 2016), also from the USA, describes challenges created by the research team. It is a comparative analysis between 4 groups aiming to understand differences according to their use (or not) of Facebook, with recommendations of a nutritional guideline (for example eating something high in fibre) or food orientations based on mindfulness (for example eat something that is homemade). The methods that were used were observation and pre and post-test questionnaires, based on mindfulness. The engagement was measured via the number of posts, likes and comments. 57 participants were recruited from Twitter, Facebook, and a mailing list. Of these, 72% took on the challenges, 46% said they wished to continue, and 95% said their awareness of the food related issues had increased. Those that answered the questionnaires said that they preferred to complete the food-based challenges than those based on mindfulness. The conclusion that was reached was that challenges based on a social component (Facebook use) promoted greater engagement, learning and interest, promoting more long-term participation and fewer dropouts. The researchers emphasize the importance that the people gave to the ease of the daily tasks. The participants considered the challenges to be a form of a game that promoted fun learning; contact with other participants was motivating and helped recording challenge practices.

The four remaining studies are part of the second set of search strings ("social network" and "challenge" and "nutrition"). The research that was undertaken by Kaipainen, Payne, & Wansink (2012), in Finland, was based on an experimental study on the National Mindless Eating Challenge (NMEC) which was an online program for healthy eating and weight loss. It aimed to understand participant retention, weight loss related results and obstacles for change. The sample was recruited via registration on the NMEC site, and initially included 2053 participants, which decreased to 504 by the end. The participants were on average 39,8 years old; 89% were women and with BMI of 28,44lbs/m2. The methods that were used were an initial profile questionnaire (demographics, physique and psychological), aiming was to discover the objectives for changing their habits: weight loss, eating healthily, eating more, or helping the family to eat better. After this initial record, the participants received environmental, behavioural and cognitive suggestions, which were related to their objectives. Together with these suggestions, there was another questionnaire that tried to determine the level of difficulty of the challenge, the predicted obstacles, and how they could be overcome. This intervention had a 75% dropout rate, and only 0,4% weight loss of those that completed it. However, how spent 3 months and answered at least 2 follow-up questionnaires lost 1% of their weight. Those who practised the challenge for more days, lost more weight than the others. The most common barriers were: inappropriate suggestions, forgetfulness, not enough time to implement change, an unexpected situation or emotional eating. The researchers believed that adherence and the effectiveness of the intervention could be improved if it was better adapted to the circumstances and psychological needs.

The study conducted by Hutchesson, Collins, Morgan, & Callister (2013), in Australia, is a comparative analysis of two paid web-based programs for weight loss: the Biggest Loser Club, and Biggest Loser Club’s Shannan Ponton Fast Track Challenge. The latter was considered to be more of a challenge because it had harder to achieve goals (loss of 1kg/week compared with 0,5kg/week), content that had more persuasive design characteristics, greater social support, was accompanied by a celebrity, had more support material and a prize was given to the leader. The researchers wanted to understand and compare weight loss through BMI, short-term dropout rates and engagement (daily use of the site and other tools). 953 participated in the standard program, and 381 participated in the challenge. In the latter 86% were women, were on average 36.7, 55% with a tendency for obesity and BMI of 30,6kg/m2. The study was observational and lasted for 8 weeks, including a questionnaire during enrolment on demographic and anthropometric data (weight and height for BMI), and weight was reported on a weekly basis. The overall dropout was 1,4% during these weeks, with a tendency to increase over time. The challenge program had greater weight loss (5,1kg x 4,5kg), a lower dropout rate (0,5% x 1,8%), greater frequency of access to the site, forums, menu plans, exercise plans and educational material. Social support was considered important to help comparisons and increase motivation. The presence of a celebrity helped increase persuasion, credibility, and this led to greater effort and better results.

The research done by Matwiejczyk, Field, Withall, & Scott (2015), also in Australia, was an experimental intervention based on challenges that were meant to increase healthy eating in participant's workplaces. The sample consisted of 411 initial participants and 269 completed the final questionnaire. The target audience were workers of enrolled companies. The study consisted of three questionnaires: an initial one given before the challenge where base information was collected; a second one, given a week later, in which the desired challenges were identified and participation was encouraged; and the final one, with a record of the challenges that were (or not) done and enquiring what really happened. In the organisations, there was a person who was kind of a facilitator that promoted and helped to enrol in the challenge. The results showed that 11 out of 12 facilitators claimed that both the challenge and the website were easy or very easy to use. Two thirds (8) of the facilitators realised that there was an increase in food awareness and that were increased conversations on healthy eating. The results of the first questionnaire showed that 80% of the participants wanted to lose weight, 56% dealt better with the environment, 50% had fun during the challenge; 40% saved money. 65% of the initial participants answered the final questionnaire, and of these participants, 90% said that they had completed the challenge, with almost 82% claiming that they had chosen healthy food over unhealthy food. At the end of the experiment, the most recurring feedback was that the people considered the challenge to be fun and not too difficult.

Lastly, the study done by MacNab & Francis (2015), USA, describes an experiment to promote eating fruit, greens, and increasing physical activity. The challenge is for the whole family, with one member enrolling the entire family. The sample was obtained through a monthly newsletter and Social Media. 20 families were registered through a site, and the majority were enrolled by a between the ages of 30 and 40 with higher education qualifications. Questionnaires were used, both before and after the challenge. The results showed an increase of 25 to 50% of fruit and greens consumption and an increase of 60 to 80% of physical activity. This study proposes a set of guidelines for creating Social Media Health Challenges: 1. Use of educational messages for the target audience; 2. Use materials and activities to follow and reinforce the weekly module’s messages; 3. Create a partnership with a local organization with the reach and resources to get to a larger audience; 4. Use Social Media to promote support and the sharing of ideas between the participants.

From the data obtained from the 6 studies, Table 3 was created, and the following conclusions reached:

There is only one study that specifically deals with challenges on Instagram, meaning that there is a big gap within this digital context;

The studies are divided into experimental and non-experimental, being conceived, planned and executed from the start by research teams and others observing already existing interventions;

Sampling is quite varied, with the biggest samples (Hutchesson et al., 2013; Kaipainen et al., 2012) coming from observational studies done by third parties;

Research has a strong quantitative component with data that is obtained by questionnaires and data collection;

Questionnaires were the most used data collection methods used;

Most studies come from the USA and Australia.

Table 3.

Characterization of the related works

| Challenges | Chung et al. (2017) | Epstein et al. (2016) | Kaipainen et al. (2012) | Hutchesson et al. (2013) | Matwiejczyk et al. (2015) | MacNab & Francis (2015) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Experimental | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Objectives | Understand the use of Instagram in diets and exercise | Understand the difference in challenges | Understand participant retention, weight loss results and barriers for change | Understand and compare weight loss through BMI, the short term dropout rate and engagement | Increase healthy eating in the workplace | Promote consumption of fruit, greens and the increase of physical activity |

| Sample | 16 people | 57 people | Initially 2053 people, at the end 504 | 953 people in the standard and 381 people in the challenge | Initially 411 people, at the end 269 | 20 families |

|

Data Collection Methods |

Semi-structured interviews | Observation, Questionnaires pre and post test | Questionnaires | Questionnaires and observation | Questionnaires | Questionnaires |

| Origin | USA, Washington University | USA, Washington University | Finland | Australia, University Drive | Australia, by Fliders University and Curtin University | USA, by Iowa State University |

| Year (ag) | 2017 | 2016 | 2012 | 2013 | 2015 | 2015 |

The Concept of Social Media Health Challenges

Since the literature review revealed that there is still few consolidated knowledge regarding a clear definition of the concept “Social Media Health Challenge”, it’s important to discuss on what can be considered a Social Media Health Challenge.

The concept of Social Media Health Challenge was sought to be understood through two different questions: what are challenges and why are challenges done, seeking to understand if a challenge is a health intervention, what are its dimensions (eating and/or physical exercise), its characteristics and its main objectives. From the six studies, four used the term intervention to describe this practice (Epstein et al., 2016; Hutchesson et al., 2013; Kaipainen et al., 2012; MacNab & Francis, 2015) and only one used a simpler word – initiative. The second aspect is related to the categories of the Social Media Health Challenge: two articles presented both, eating healthy and exercise (Hutchesson et al., 2013; MacNab & Francis, 2015) and three had only one category, that of healthy eating (Chung et al., 2017; Epstein et al., 2016; Matwiejczyk, Field, Withall, & Scott, 2015). However, one work was directed primarily towards eating behaviour, whilst including a small task related to physical exercise (Kaipainen et al., 2012).

All of the studies stated that the main objective of the challenge was weight change (in most cases weight loss), which should be achieved through behaviour change. Another aspect that was mentioned by all studies was the use of some type of digital technology, either mobile devices (Epstein et al., 2016), e-mails (MacNab & Francis, 2015), websites (Hutchesson et al., 2013), SMS (Hutchesson et al., 2013) or social networks (MacNab & Francis, 2015), showing a clear tech support. Another characteristic that was emphasised was that these interventions were implemented via the use of smaller objectives (Epstein et al., 2016) suggestions (Kaipainen et al., 2012) and actions referred to as challenges (Epstein et al., 2016; Hutchesson et al., 2013; MacNab & Francis, 2015; Matwiejczyk et al., 2015). This is intended to provide greater feasibility to participant, and better perception about what to do and about their current state of progress. Another important aspect was that in the majority of cases challenges should be done based on everyday interventions (Epstein et al., 2016; Kaipainen et al., 2012; Matwiejczyk et al., 2015); health interventions should be simple and done on a daily basis. Table 4 summarizes the analysis present in this section and allowed the systematization of the following definition:

Table 4.

Characteristics of Social Media Health Challenges

| Challenges | Chung et al. (2017) | Epstein et al. (2016) | Kaipainen et al. (2012) | Hutchesson et al. (2013) | Matwiejczyk et al. (2015) | MacNab & Francis (2015) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of the term intervention | - | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Dimension | Eating | Eating | Eating (mostly) | Eating and physical exercise | Eating | Eating and physical exercise |

| Challenge objective | Weight change | Weight change | Weight change | Weight change | Weight change | Weight change |

| Most reported characteristics | Considerable technological support and sub-tasks | Considerable technological support and sub-tasks | Considerable technological support and sub-tasks | Considerable technological support and sub-tasks | Considerable technological support and sub-tasks | Considerable technological support and sub-tasks |

Social Media Health Challenges is a health initiative or intervention which the main objective is weight change, through behaviour change based on healthy eating and physical exercise routines; these consist of a small number of tasks that easy to achieve and that have considerable digital technological support through social media.

Social Media Health Challenge Mechanisms

In this final section, the mechanism of Social Media Health Challenges and how they occur is studied, as well as the actors involved in their execution, and their duration. To better understand the process in which the challenge is part of, the theories of behaviour change, challenge distribution configuration and digital support artefacts are used.

Of the six studies that were analysed, only three clearly mentioned behaviour change theories; in two cases mindfulness and mindless eating techniques were found (Epstein et al., 2016; Kaipainen et al., 2012) and one case the persuasive design is used (Hutchesson et al., 2013). It is worth mentioning that one of the initial objectives was to identify behaviour theories referred by Bartholomew et al. (2006) were not achieved, because none of these 3 theories correspond to those mentioned by authors, which are most used in health interventions (Table 5).

Table 5.

Social Media Health Challenge mechanism

| Challenges | Chung et al. (2017) | Epstein et al. (2016) | Kaipainen et al. (2012) | Hutchesson et al. (2013) | Matwiejczyk et al. (2015) | MacNab & Francis (2015) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behaviour change techniques | - | Mindfulness eating | Mindless eating | Persuasive Design | - | - |

| Sub-tasks designated as challenges | - | x | x | x | x | x |

| Weekly distribution | - | - | - | x | x | x |

| Daily distribution | - | x | x | - | - | - |

| Practical tools | - | x | x | x | x | x |

| Social environment concerns | - | - | x | - | - | |

| Technologic Support | ||||||

| Web sites | - | - | x | - | x | x |

| E-mails | - | - | - | - | x | x |

| Printed materials | - | - | - | - | x | x |

| Power Point | - | - | - | - | x | - |

| Facebook page | - | x | - | - | - | x |

| Twitter page | - | - | - | - | - | x |

| App with a photographic eating 'diary' | - | x | - | - | - | - |

| Content | ||||||

| Recipe | - | - | - | - | x | x |

| Motivational tips and nutritional information | - | - | - | - | x | x |

| Shopping lists | - | - | - | - | - | x |

| List of physical exercises | - | - | - | - | - | x |

| Small challenges | - | - | - | - | x | x |

The challenge activities varied a lot, according to the nature and objectives of the interventions. However, there were consistent patterns to be found in interventions (Table 5). Besides that, it worth to highlight there was a concern in terms of ease of execution, with practical tools being made available (Epstein et al., 2016; Hutchesson et al., 2013; Kaipainen et al., 2012; MacNab & Francis, 2015; Matwiejczyk et al., 2015) (Table 5). Only one was explicitly concerned for the social environment (Kaipainen et al., 2012), a flaw in others that clearly needs rethinking (Table 5). The technologic support was diversified, but only one challenge used a mobile App with a photographic eating 'diary' (Epstein et al., 2016) (Table 5). The kind of challenge content varied, according to the objectives of the interventions (Table 5). The Chung work is not an intervention, but is a user experience report through interviews, because of this, it is not detailed challenge aspects (Table 5).

The study that stated to have used the largest number of tools and content was the one that had the greatest weight loss: Hutchesson et al. (2013). This study focused on observing and analysing paid interventions and separated the support tools and challenge implementation into 6 categories, of which 3 were technological: self-monitoring (a diary of food and exercise, weight logs, waist and hip measurements with a silhouette change graph); feedback (calculation of the energetic balance goal, automatic feed but personalised in terms of consumption and calorie burning with feedback based on the level of success); and reminders/prompts (mails and SMSs). The other 3 categories were: diet and exercise recommendations (eating plan and calorie consumption); educational material (menu plan, shopping list, exercise plan, a video of the challenge demonstrated by a celebrity); and social support (forum, video blog, weekly online chat meetings, Facebook groups, questions and challenges led by a celebrity).

Only 3 studies identified differing roles between the participants according to their function in the challenges: (i) a facilitator, which did the enrolment and stimulated participation (Matwiejczyk et al., 2015); (ii) a person that registered during intervention (MacNab & Francis, 2015); (iii) a person that motivated and helped with doubts, which in this case was a celebrity related to weight loss in the study referred to above (Hutchesson et al., 2013). Time spent in interventions varied from 3 weeks to 2 months, which is a period of time that can lead to behaviour change but is not enough to verify a long-term change.

Analysis of Instagram Health Challenges

The first part of this study defined the concept of Social Media Health Challenges, given how little information there is on this topic. Furthermore, there were few studies that describe the current ongoing practices in this field. As such, there was the need to fill this gap, analysing the online practices that currently are being supported by Instagram. This second step was anchored in a previous work of the research project that frames this paper, already described (Saboia et al., 2018), which discussed the role of Opinion Leaders (Nutritionists, Healthy Lifestylers and POLs) in food behaviour change. In that work, the Instagram profiles of 115 Nutritionists, 50 Healthy Lifestylers and 50 POLs have been analysed.

From those profiles, and for the purpose of this analysis of Instagram Health Challenges, 50 profiles of each group were considered (in the case of the Nutritionists, the 50 profiles with the most followers were selected). The search and observation of Instagram profiles were based on the incognito browser setting. All material observed and analysed was documented on print screens, and it was saved and organized for future researches. Besides that, all observations were quantitatively analysed, which resulted in the description of the Social Media Challenges through patterns of frequency and average. The presence of the word 'challenge' was verified in these 150 profiles: in the first image of a post (video or photo), throughout the previous 52 weeks (a year) from each profile, starting from the second week of April 2018; in all of the titles of recorded stories3; and in all icons from the recorded stories. Then the text that described each challenge in a post was read, the images and audios associated to each story were analysed, and a set of posts and stories were associated to each challenge, according to the name and time in which it occurred. This was necessary because each challenge can have different posts and stories, meaning that challenges were considered different even if they had the same name, as long as they occurred at different times, like: the challenge of a Healthy Lifestyler was considered for seven times, as it occurred during different periods and could have different characteristics.

This analysis was registered in a grid created according to the obtained data, and special attention has been given to the use of specific hashtags that were directly associated with challenges. Searching based on this component led to the conclusion that the Top Posts that were trending on Instagram were tagged with this hashtag or place4. Instagram creates a maximum of 9 Top Posts by hashtags. These Top Posts were observed and analysed, and the grid used to display the results is presented below. All posts and stories associated with the challenges were recorded.

The inclusion criteria for analysis of Social Media Health Challenges were the following: these initiatives should be aligned with the concept of Health interventions aiming at weight change; promote behaviour change based on healthy eating and physical exercise routines, and have digital technological support. The following were also included: all posts that promoted challenges, even if on other media (such as closed groups on Facebook, groups on WhatsApp and/or special platforms); ongoing challenge posts, which due to low prevalence led to extending for posts since 52 weeks ago (from the second week of April 2018); brand-sponsored challenges; challenge posts that were paid or free, a category that was initially unforeseen but emerged as a new category; and challenge posts that were promoted by the Opinion Leaders, even if they were conceived with others or solely by others and which became another emergent category (Bardin, 2011).

Excluded from the analysis were: posts that included actions that occurred only during a specific video (such as a challenge in which the Nutritionist asked her followers to go through a chocolate corridor whilst doing physical exercise); posts that called their methods project, workshop, lessons, or programs, as these required greater analysis to see if they could be considered Social Media Health Challenges; posts that mentioned challenge, but didn't put forward a dietary or physical exercise routine, like for example nutritionists that criticised this type of intervention; challenge posts that were not focused on weight change, via slimming or gaining muscle mass (like a POL that challenged followers to relinquish material things, giving away clothes and other objects); all posts that did not include the word challenge, even if there was a before and after photo of a person (that was not the Opinion Leaders) and challenges that were on other media or online social networks, even if referred to. In some cases, so as to complete the information needed, other Instagram profiles of participants were seen. In other cases, some of the content provided by challenges was not accessible as this is often only available in enrolment or in daily stories that are deleted after 24 hours. The final analysis of the challenges was organised in a grid, with each objective of each field being described in Table 6.

Table 6.

Dimensions of analysis grid

| Dimension | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Profile | Identifiable by the profile's user name or by the name given by Instagram.1 |

| URL | Profile location via web browser. |

| Category | According to the study of Saboia et al., 2018. |

| Quantity of Followers | Number of followers, as a function of Instagram. |

| Name | Name given by the Opinion Leaders for the challenge. |

| Objectives | Weight loss, muscle mass gain, or maintaining weight. |

| Behaviour to follow | List of behaviour to follow within the challenge. |

| Duration (days) | Number of days that the Opinion Leader designates for the challenge. |

| Producer | Challenges that the Opinion Leader conceives alone or with the participation of others. When this does not occur, the Opinion Leader is considered to be a challenge promoter. This category appeared as a result of the analysis, as described above . |

| Specific Hashtag | Hashtag that is associated to the challenged referred to by the Opinion Leader. |

| Quantity of Posts | Quantity of posts associated to the Hashtag of a specific challenge (considered for only once when more than one challenge was associated to the same hashtags). |

| Top Posts | Analysis of content associated to the Top Posts of hashtags of a specific challenge. The analysis categories were based on the analysis of these posts, as described below. |

| Support artefacts | Technology used, such as a closed group on Facebook. |

| Content | Types of content promoted by Opinion Leaders via technological media, subcategorised into: food information, shopping lists, recipes, substitutions, exercise types, daily tasks, motivational types, and goals to achieve. |

| Wider ranging hashtags | The Opinion Leader uses a set of hashtags of wider scopes. |

| Neknomination | Tag friends to see or participate in the challenge. |

| Enrolled challenge | A challenge which requires enrolment to participate and access associated content (this category emerged as a result of the analysis). |

| Paid challenge | A challenge that involved payment to participate (this category emerged as a result of the analysis). |

| Prizes | Prizes for participants that stood out. |

| Components | If there are guidelines related to eating, physical exercise or psychological-cognitive aspects, such as habits, motivation, attitudes etc. |

| Habits (Rothman et al., 2009) | When the Opinion Leader refers to habits. This category was analysed in posts, Top Posts, and stories associated with the challenge. |

| Model (Bandura, 1977) | When the Opinion Leader presents themselves as a model to be followed, referring to their behaviour, presenting their body and their process of achieving the required goals. This category was analysed in posts, Top Posts, and stories associated with the challenge. |

| Behavioural theories (Bartholomew et al., 2006) | Behavioural theories referred by Opinion Leader for challenge. |

From studying all of the Top Posts, some categories emerged (Bardin, 2011) that were associated with the content and were formatted according to defined criteria. The content also had its origin categorised, whether it came from third parties, whether followers or Opinion Leaders (Nutritionists, Healthy Lifestylers and POLs). The concepts related to each category and were applied in the content analysis are listed in Table 7.

Table 7.

Dimensions of content Top Post analysis grid

| Dimensions | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Eating | The following types of posts were considered: photo of a meal, information on a specific food diet, information on macro or micro nutrients, eating tips. |

| Challenge report | Content related to the challenge experience |

| Challenge (enrolment and functioning) | Challenge enrolment and functioning, like for example content on printed material, events, launch, results, meetings with challenge followers, etc. |

| Before and After | Photo-montage of a before and after challenge photo |

| Recipes | Food recipes |

| Exercises | Suggested exercise list, exercise demonstration, exercise execution and their reports. |

| Other weight loss challenges | Content from weight loss challenges from other profiles |

| Humour and Dynamics | Humorous content and/or dynamics referring to challenges |

| Psychological-cognitive message | Content related to motivation, self-control, habits, balance, and faith, among others. |

| Weight loss experience | General tips for the process |

| Model | Opinion Leaders present themselves as a model to be followed, showing photos of their current body. |

| Weight | Presenting an image showing their measured weight |

| Water intake | Content that tries to promote water intake |

| Adverts | Contents that seek to promote and sell third party goods or services |

| Other challenges | Content of challenges that are not weight loss related |

| Challenge partners | Opinion Leaders present their challenge partners |

| Travel | Opinion Leaders are seen to be travelling |

| Diseases related to obesity | Opinion Leaders present content about diseases that can be related to obesity |

| Obesophobia | Content related to obesity prejudice |

Results

Results were analysed considering the three profiles defined in the previous work (Saboia et al., 2018): 50 Nutritionists, 50 Health Lifestylers and 50 POLs. In total, challenges were promoted by 28 profiles, being the most promoted by POLs, of the 50 POLs (N=16 - 32%), then by Health Lifestylers (N=8 - 16%) (HL), and finally by Nutritionists (N=4 - 8%). This result was further confirmed by the number of challenges made. There were 39 challenges promoted by the 16 POLs. Similar characteristics were found in the 8 Health Lifestylers that did 19 challenges. The 4 nutritionists that were considered did 5 challenges. This meant that a total of 63 challenges were analysed (Table 8).

Table 8.

Sample, Challenger profile, Challenges and Followers

| Nutritionists | Health Lifestylers | POLs | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial sample | 50 | 50 | 50 | 150 |

| Challenger Profile (n - %) | 4 – 8% | 8 – 16% | 16 – 32% | 28 |

| Challenges | 5 | 19 | 39 | 63 |

| Number of followers (thousand) | 253.000 to 89.000 | 530.000 to 100.000 | 579.000 to 42.300 | 6.326.800 |

| Average of followers (by Opinion Leader) | 166.750 | 260.375 | 223.550 | 225.957 |

Another issue related to challenge conception is the number of followers that partake in the challenges. As a primary attribute that differentiates the potential of each profile, the number of followers was considered, with the nutritionists having an average of 166.750 followers (253 to 89 thousand), the Health Lifestylers 260.375 followers (530 to 100 thousand followers) and the POLs with 223.550 followers (579 to 42,3 thousand), with an overall average of de 225.957 followers (Table 8).

The names of each challenge were also analysed. Only 4,76% (N=3) didn't have names, showing that naming was important for the Opinion Leaders. Names were created towards motivating followers. In 42,85% (N=27) they were related to the objectives to be achieved, 33,33% (N=21) associated to the Opinion Leader's name/profile, 23,80% (N=15) the type of food/diet, 22,22% (N=14) the challenge duration, 17,46% (N=11) the time of the year, 4,76% (N=3) the community and 3,17% (N=2) physical exercise (Table 9). Some challenges included multiple categories.

Table 9.

Aspects related to challenges names

| Aspects related to name | Nutritionists | Healthy Lifestylers | POLs | Total - N | Total - % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objectives to be achieved | 2 | 6 | 19 | 27 | 42,85% |

| Associated to the Opinion Leader's name/profile | 1 | 9 | 11 | 21 | 33,33% |

| Type of food/diet | 1 | 3 | 11 | 15 | 23,80% |

| Challenge duration | 3 | 2 | 9 | 14 | 22,22% |

| Time of the year | 1 | 0 | 10 | 11 | 17,46% |

| No name | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4,76% |

| Community | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 4,76% |

| Physical exercise | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3,17% |

| Others | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3,17% |

The final objective of each challenge was analysed: weight loss, maintaining weight, or muscle mass increase. From the 63 challenges, 96,82% (N=61) focused on weight loss, with only 3,17% (N=2) focusing on muscle mass increase (in the HLs category) and none weight maintenance (Table 10). Social Media Health Challenges seem to be overwhelmingly focused on weight loss.

Table 10.

Challenge Objectives

| Challenge Objectives | Nutritionists | Health Lifestylers | POLs | Total | Total - % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight loss | 5 | 17 | 39 | 61 | 96,82% |

| Muscle mass increase | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3,17% |

| Weight maintenance | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0% |

To achieve the challenge objective, the Opinion Leader promotes a specific behaviour. The analysed challenges promoted different behaviours, as follows: Practicing physical activities (N=17), Increase liquid intake (water and tea) (N=13), Increase fruit, Vegetables and greens intake (N=11), Food substitutions (N=8), Eating 'real' food (N=6), Eating healthy food (N=4), Controlling stress or meditating (N=5), Sleep (N=5), Reducing or eliminating intake of: sugar (N=11), fried food/artificial fat (N=8), white flour (N=9), soft drinks (N=9), refined (N=4), refined juice (N=3), and alcohol (N=2) (Table 11). In some cases, it was not possible to find a specific behaviour.

Table 11.

Specific behaviour proposed by Opinion Leader

| Specific behaviour | Nutritionists | Healthy Lifestylers | POLs | Total - N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practicing physical activities | 0 | 8 | 9 | 17 |

| Increase liquid intake | 0 | 4 | 9 | 13 |

| Increase fruit, vegetables and greens intake | 0 | 4 | 7 | 11 |

| Food substitutions | 0 | 2 | 6 | 8 |

| Eating 'real' food | 0 | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Eating healthy food | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Controlling stress or meditating | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Sleep | 0 | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Reducing or eliminating intake of sugar | 1 | 3 | 7 | 11 |

| Reducing or eliminating intake of fried food/artificial fat | 0 | 1 | 7 | 8 |

| Reducing or eliminating intake of white flour | 0 | 3 | 6 | 9 |

| Reducing or eliminating intake of soft drinks | 0 | 2 | 7 | 9 |

| Reducing or eliminating intake of refined | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Reducing or eliminating intake of refined juice | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Reducing or eliminating intake of alcohol | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Others | 0 | 5 | 5 | 10 |

The behaviour is to be done over a period of time, with the most common being 21 days (30,15%, N=19), followed by 30 days (15,87%, N=10) (Table 12). However, there are only 9 cases that do not refer to a specific period of time.

Table 12.

Social Media Health Challenges duration

| Duration (days) |

Nutritionists | Healthy Lifestylers | POLs | Total - N | Total - % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3,17% |

| 40 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 9,52% |

| 30 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 10 | 15,87% |

| 21 | 1 | 3 | 15 | 19 | 30,15% |

| 15 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 9,52% |

| 14 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1,58% |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3,17% |

| 7 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 9,52% |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1,58% |

| 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3,17% |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1,58% |

| - | 0 | 2 | 7 | 9 | 14,28% |

An issue that was also analysed was the production of the challenge, i.e. if it was conceived by the Opinion Leaders. As such, 88,88% of the challenges were created by the profile owners (Nutritionists=5, HL= 18, POLs = 33) (Table 13).

Table 13.

Social Media Health Challenges by producer

| Production | Nutritionists Challenges | Healthy Lifestylers Challenges | POLs Challenges | Total - N | Total - % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opinion Leaders | 5 | 18 | 33 | 57 | 88,88% |

| Third Party | 0 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 11,11% |