Abstract

The fundamental aim of this study is to determine the effects of prolonged usage of N95 respirators and surgical facemasks amid health care workers in our institution. Cross-sectional study. SRM medical college hospital, Kattankulathur. A self-constructed questionnaire containing 20 queries regarding the effects of prolonged use of face masks, after being analysed by the experts of our institution were handed over to 250 participants.. All participants wore either surgical masks or N95 respirators for a minimum of 4 h per day. People aged between 20 and 48 years were selected for this study. Study period was from 20/07/2020 to 26/07/2020. Completed questionnaires were sent for statistical analysis. A total of 250 healthcare workers participated in the study, out of which 179 were females. The acquired results were excessive sweating around the mouth accounting to 67.6%, difficulty in breathing on exertion 58.2%, acne 56.0% and itchy nose 52.0%. This study suggests that prolonged use of facemasks induces difficulty in breathing on exertion and excessive sweating around the mouth to the healthcare workers which results in poorer adherence and increased risk of susceptibility to infection.

Keywords: N95 respirators, Surgical masks, COVID-19, Healthcare workers

Introduction

The nose is a complex organ that forms an important part of the face and has multiple functions. The primary function of the nose is to humidify,warm the inspired air and also aids at removing the harmful particles from entering into the lower respiratory tract. It is the frontline defender of the respiratory system. An average adult usually inspires about 10,000 L of air daily. Nasal mucosa is a highly vascular structure and has a large surface area of 150 cm square. Physiologically, the nose has 50% resistance in the entire airway, which when affected plays a significant role in total respiratory function. All of these components contribute to normal homeostasis of the body [1].

Slight fluctuations in the external environment can affect the function of cilia. Dry conditions hinder ciliary action thereby stopping ciliary movements at temperatures below 10 degree Celsius and temperatures above 45 degree Celsius [1]. Cilia can beat above pH-6.4 as well as function in a slightly alkaline medium of up to 8.5 for a prolonged period [1].

The normal inspiratory flow rate in an adult ranges between 5L-12 L/min and has pressure of 50 Pa between the nostrils and nasopharynx. During exercise the flow rate can increase as much as 150L/min [1].

The velocity of air increases as it passes through the nasal valve. A turbulent flow is observed in the nasal cavity, with different air layers swirling together [1]. The change from laminar to turbulent flow is paramount as it allows the velocity of air to reduce, thus allowing prolonged contact of inspired air with nasal mucosa,thereby enabling the nose to perform its vital function [1].

The inferior turbinate is also a part of nasal valve area where it plays a vital role in changing the laminar air flow to turbulent. The large surface area and extensive blood supply to the inferior turbinate increases the association of inspired air with the nasal mucosa which enables the nose to carry out its functions more efficiently [1].

The turbinate assembles the pattern of airflow, enabling the nose to exhale inspired air into the airstream. In this process, heat and energy are emitted into the inspired airstream. As a consequence, saturation of the airborne particles and microorganisms becomes heavier and sinks into the mucosal layer where they are processed by enzymes and immune system cells [1].

Temperature of the inspired air ranges from −50 °C to 50 °C. It usually depends on the temperature of the local environment [1].

Negus et al., stated that moistening of the surface of the respiratory mucosa largely depends on the secretion from racemose mucous glands and transduction through cell walls. A combination of these two produces mucus [2]. Nose has numerous goblet cells and glands with good vascularity. Nose eminently gives moisture of about one litre in 24 h, which is basically lost during expiration [2].

A few parameters should be considered when we are analysing about the moisture of the atmosphere.

The carrying power of the atmosphere for water is termed as Absolute Humidity. This varies directly with the temperature and barometric pressure [2].

If the quantity of water surpasses the maximum, the excess is precipitated as droplets; hence dew point is reached [2].

Relative humidity is the estimate of the quantity of the water vapour to the total amount of vapour that can exist in the air at present temperature [2].

The heat emitted by the blood helps in warming the inspired air and raises it to the body temperature. The air reaching the larynx should be warmed to bring higher absolute humidity [2].

Facemasks are of vital importance in protecting the healthcare workers from the Corona virus disease(SARS-COV 2).The World health organisation(WHO) announced the pandemic of COVID-19 on 11th March 2020 [3].The use of face masks have become ubiquitous to prevent the spread of COVID-19.It has been recommended by the governments to enforce their mandatory use. About 20.9 million people are affected with the Coronavirus as of 12th of August 2020 [4]. In India, about 2.39 million people have been affected with the Corona virus as of 13th of August 2020 [5].

A study done by Antonio Scarano et al. [6], states that N95 respirators were able to persuade a raise in facial discomfort, facial skin temperature resulting in lower compliance on comparing with surgical masks. Owing to the prolonged usage of facemasks, there might be an increase in heat beneath the mask, which in turn decreases the water carrying capacity of air in the nose resulting in the sensation of dry nose. A study by Raymond Roberge et al., stated that increased thermal perception is one of the reasons for the intolerance of wearing N95 respirators [7]. Based on these background findings, in this study we are going to assess whether the prolonged usage of face mask will have effects on the thermal reaction of facial skin and nasal cavity, which can lead to improper usage of the facemasks.

Methods

A self-constructed questionnaire was made based on the interview with 250 healthcare workers and it was further analysed and assessed by the experts. A final questionnaire of 20 were given to the participants which includes feeling of generalised nasal discomfort, dry nose, itchy nose, burning sensation in the nose, cracking inside the nose, crusting, pain in the nose, altered sense of smell, blood in the tissue paper, nasal stuffiness, acne, skin changes like any rashes or redness over the face, pain in the ear, dry mouth, halitosis, sore throat, trouble breathing on exertion, dry eyes and excessive sweating.

This is a Cross-sectional study conducted in SRM Medical College Hospital and Research institute, Chennai. A total of 250 health care workers were analysed during this study period. All participants wore both the surgical masks and N95 respirators for a minimum of 4 h per day.

Inclusion criteria was healthcare workers aged 18–45 years and those willing for the study. Young people were selected as they represent the most active, healthy population. Exclusion criteria included non—healthcare workers and those with co-morbidities like diabetes, hypertension, epilepsy, cardiac illness, asthma and other respiratory illness.

Statistical Analysis

The outcome of the data was assembled and statistically assessed by RStudio 1.3.1073. The particulars was assessed by Shapiro–Wilks test to estimate the normal distribution. The Z-Proportion test was carried out to note the study variables proportion in every complaint. The significance level was calibrated at p < 0.05.

Results

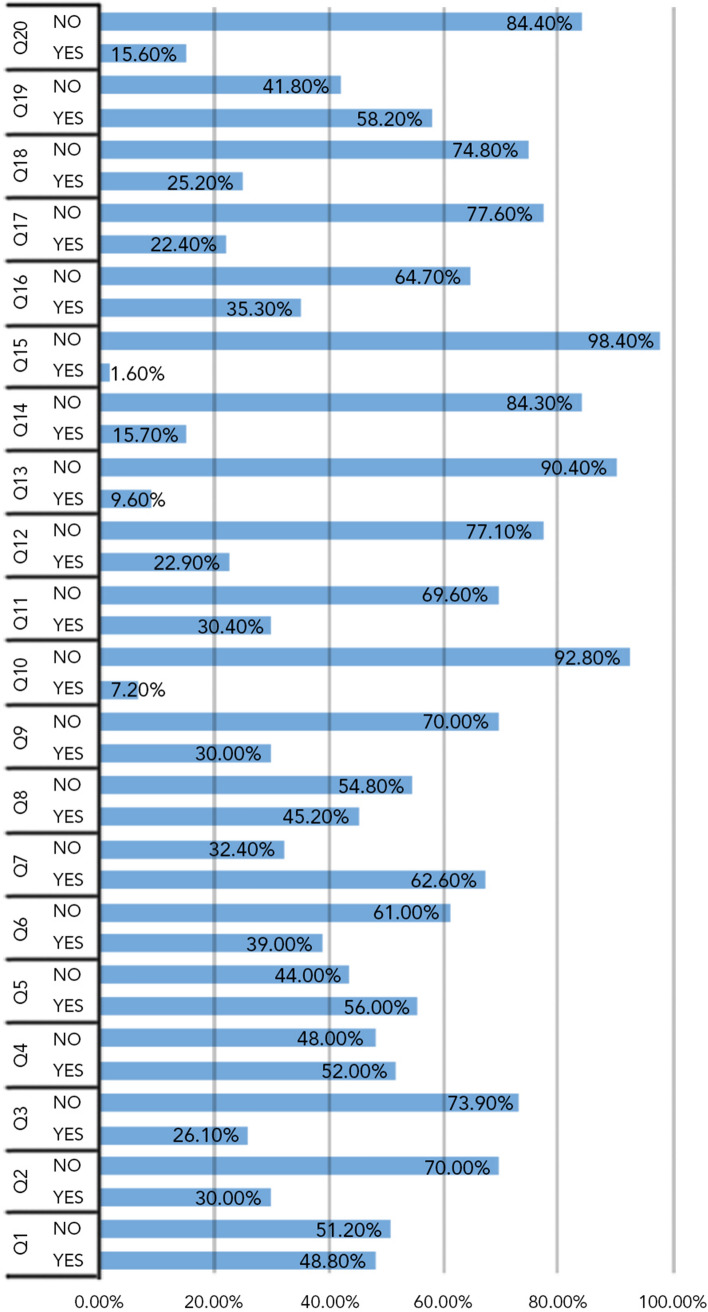

A total of 250 health care workers were given the questionnaire of which females were 71.6% (176) and males were 28.4% (71). All the 250 health care workers were included in the final analysis.The mean age group was 25.843 (Age range 20–48). Of these 250 participants, 48.8% experienced generalised nasal discomfort, 30.3% dry nose, 26.1% burning sensation in the nose, about 52.0% developed itchy nose, 56.0% acne in the face, 39.0% experienced redness on the face and 67.6% developed excessive sweating around the mouth (Tables 1, 2). These symptoms were mainly caused due to the hot and humid air in the dead space beneath the mask in comparison to the ambient temperature. About 30.0% developed pain on the nose and 45.2% had pain behind the ear which are possibly due to the tight fitting masks (Table 3). In Table 4, about 58.2% of the participants developed trouble breathing on exertion while wearing masks which is probably due to the tight mask causing hypercapnic hypoxic environment leading to numerous physiological alterations such as cardio-respiratory stress and metabolic shift. The rest of the symptoms in Table 4 such as dry mouth sensation accounting to 35.3%, halitosis about 22.4%, sore throat attributing to 25.2% are likely due to inadequate consumption of water during prolonged usage of facemask. A small proportion of healthcare workers were observed with the symptoms of altered smell (7.2%), sense of nasal stuffiness (30.4%), nasal block (22.9%), cracking sensation (9.6%), crusting in the nose (15.7%) and blood on tissue paper (1.6%) (Tables 5, 6). Despite our study’s strength, including comprehensive search strategy for data and literature a thorough assessment should be done to improve the quality of evidence by using validated tools.After performing a z-proportion test we found all the complaints except those of Q1 and Q3, statistically significant beyond the usual alpha-level of 0.05. Figure 1 shows the percentage of symptoms in the participants.

Table 1.

Stating statistical analysis of subjective nasal symptoms

| Frequency | Percent | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Feeling of generalized nasal discomfort | Yes | 122 | 48.80% | z-value | 0.5 | Statistically not significant |

| No | 128 | 51.20% | P value | 0.5915 | |||

| 2 | Feeling of dry nose | Yes | 75 | 30.00% | z-value | 8.9 | Statistically significant |

| No | 175 | 70.00% | P value | < 0.001 | |||

| 3 | Feeling of hot or burning nose | Yes | 65 | 26.10% | z-value | 10.5 | Statistically significant |

| No | 184 | 73.90% | P value | < 0.001 |

Table 2.

Stating statistical analysis of skin symptoms

| Frequency | Percent | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | Feeling that your nose is irritated/itchy | Yes | 130 | 52.00% | z-value | 0.5 | Statistically not significant |

| No | 120 | 48.00% | P value | 0.58 | |||

| 5 | Noticed any acne (pimples) on the face | Yes | 140 | 56.00% | z-value | 2.7 | Statistically significant |

| No | 110 | 44.00% | P value | < 0.001 | |||

| 6 | Noticed any skin rashes/redness on the face | Yes | 97 | 39.00% | z-value | 8.5 | Statistically significant |

| No | 152 | 61.00% | P value | < 0.001 | |||

| 7 | Experienced excessive sweating around the mouth | Yes | 169 | 67.60% | z-value | 8 | Statistically significant |

| No | 81 | 32.40% | P value | < 0.001 | |||

Table 3.

Stating statistical analysis of pressure symptoms

| Frequency | Percent | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | Experienced pain behind the ear | Yes | 113 | 45.20% | z-value | 1.8 | Statistically significant |

| No | 137 | 54.80% | P value | < 0.001 | |||

| 9 | Pain in the nose | Yes | 75 | 30.00% | z-value | 8.9 | Statistically significant |

| No | 175 | 70.00% | P value | < 0.001 | |||

Table 4.

Showing statistical analysis of supplementary complaints

| Frequency | Percent | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | Experienced dry mouth | Yes | 88 | 35.30% | z-value | 6.7 | Statistically significant |

| No | 161 | 64.70% | P value | < 0.001 | |||

| 11 | Experienced halitosis (bad breath) | Yes | 56 | 22.40% | z-value | 12.5 | Statistically significant |

| No | 194 | 77.60% | P value | 0 | |||

| 12 | Experienced sore throat | Yes | 63 | 25.20% | z-value | 11.2 | Statistically significant |

| No | 187 | 74.80% | P value | < 0.001 | |||

| 13 | Experienced trouble breathing on exertion | Yes | 145 | 58.20% | z-value | 3.6 | Statistically significant |

| No | 104 | 41.80% | P value | < 0.001 | |||

| 14 | Experienced dry eyes | Yes | 39 | 15.60% | z-value | 15.7 | Statistically significant |

| No | 211 | 84.40% | P value | < 0.001 |

Table 5.

Stating unusual nasal complaints

| Frequency | Percent | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | Feeling that skin inside your nose is cracking | Yes | 24 | 9.60% | z-value | 18.1 | Statistically significant |

| No | 226 | 90.40% | P value | < 0.001 | |||

| 16 | Crusting in the nose | Yes | 39 | 15.70% | z-value | 15.7 | Statistically significant |

| No | 210 | 84.30% | P value | < 0.001 | |||

| 17 | Noticed blood on tissue paper | Yes | 4 | 1.60% | z-value | 21.5 | Statistically significant |

| No | 246 | 98.40% | P value | < 0.001 | |||

Table 6.

Showing statistical analysis of nasal complaints

| Frequency | Percent | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | Noticed an altered sense of smell | Yes | 18 | 7.20% | z-value | 18.8 | Statistically significant |

| No | 232 | 92.80% | P value | < 0.001 | |||

| 19 | Nasal congestion or stuffiness | Yes | 76 | 30.40% | z-value | 9.4 | Statistically significant |

| No | 174 | 69.60% | P value | < 0.001 | |||

| 20 | Experienced any Nasal blockage or obstruction | Yes | 57 | 22.90% | z-value | 12.1 | Statistically significant |

| No | 192 | 77.10% | P value | < 0.001 | |||

Fig. 1.

Shows percentage of symptoms manifested in the participants on prolonged usage

Discussion

In this study, among the 250 participants the outcome suggests that continuous usage of facemasks can lead to a wide spectrum of nasal discomfort and complaints pertaining to the facial skin and oral cavity due to its prolonged usage.There is a decrease in humidification of air beneath the facemask and decrease in transpiration of the skin around the nasal and perioral region. In this current study, we found that 48.8% of the participants had generalised nasal discomfort on wearing the facemask for a prolonged period of time.

Facemasks protect against harmful microorganisms and its utilisation is essential during the pandemic. Facemasks prevent transpiration, increase perspiration and temperature in perioral region which could possibly be due to decreased transpiration.

Wearing the facemask for a prolonged period causes reduced heat loss from the body by various mechanisms such as conduction, convection, evaporation and radiation [8]. The difference in temperature around the outer surface of the respirator and the environment there is a relative increase in warmth and dampness of the expired air causing the condensation of moisture on the respirator. This phenomenon impairs respiratory heat loss thereby increasing the heat burden. Facemasks prevent normal transpiration and the dead space underneath the facemasks is filled with hot, humid expired air respiratory cycle. Since facemasks cover both nose and mouth it results in decrease in cooling impact of the facial temperature. DuBois et al. stated that skin temperature > 34.5 degree Celsius is not acceptable due to the increased thermal sensation and results in significant discomfort to the wearers [9].

Certain articles have stated a high temperature in the cheek underneath N95 facemasks [10]. In the current study, we found about 67.6% of healthcare workers have developed excessive sweating around the mouth. As a result of the discomfort caused by the facemasks the subjects tend to touch the facemasks at frequent intervals and it can lead to contamination of the hands leading to more disseminated infections.

Simulated nasal breathing while performing moderate exercise in a comfortable surrounding showed that conditioning capacity of air decreased to 11% due to brief existence of inspired air in the nose. When the effort increases, the air conditioning capacity significantly decreases [11]. Another study stated that temperature and the quantity of water delivered by expired air is notably higher with mouth breathing in comparsion with nasal breathing. Therefore the net respiratory heat loss is higher with oro-nasal breathing than nasal breathing during exercise [12]. In our study also we assessed that about 58.2% of the participants had trouble breathing on exertion with the facemasks on.

There has been an increased incidence of skin conditions in healthcare workers due to the extended use of facemasks. Contact dermatitis, contact urticaria occurs due to adhesives, rubber in straps, free formaldehyde released from the non-woven polypropylene and from metal in clips [13]. Foo et al., analysed healthcare workers during the SARS pandemic in 2003 at Singapore, and reported that 51.4% experienced itch induced by face masks [14]. In an experimental study by Roberge et al., of a group of 20 healthy people wearing surgical masks during continuous walking on a treadmill at a low–moderate work rate (5.6 km/h) for 1 h, facial itch occurred in 7% of participants, and an additional 11% experienced skin irritation [7]. In the current study we found that about 52.0% of the participants have developed itch in the nose or irritation in the nose.

Zuo et al., [15] showed that pre-existing acne, rosacea and seborrheic dermatitis were exacerbated by using face masks. This is in accordance with the opinion expressed by a group of Chinese experts [16].In the current study, about 56.0% of the participants developed acne and about 39.0% of the participants developed redness on the face. Around 30.0% of the participants developed pain in the nose and 45.2% proportion of the participants developed pain behind the ear due to elastic straps of the face masks.35.3% of the participants developed dry mouth and 22.4% had developed halitosis due to the prolonged usage of the facemask.

In this study,we also found that about 30.4% of the participants had the sense of nasal stuffiness,30.0% of participants had the sense of dry nose,26.1% developed the feeling of hot burning sensation in the nose and about 22.9% of the participants have actually developed nasal obstruction following prolonged usage of facemask.

The study with 250 healthcare workers is adequate enough for the technical hypothesis but insufficient for evaluation of multifactorial effects. If we had involved people with cardiac, pulmonary co-morbidities in the study, it would result in a significant change in the results of the study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the use of facemask plays a pivotal role in causing significant discomfort in all the participants during its prolonged usage which can limit the efficient usage of facemask, leading to decreased protection. Since facemasks are essential to protect us from COVID-19, certain strategies can be followed to reduce the heat burden due to its prolonged usage such as encouraging nasal breathing, pre-use refrigeration of the respirator.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors hereby declare that there is no potential conflicts of interest with respect to research and publication of this article.

Ethical Standards

As it is a study involving human participants,Ethical clearance was obtained from the institution.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained for all participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tira G, Shahzada KA, Physiology of nose and paranasal sinuses; scott brown 8th edition, pp 983–988

- 2.Negus VE (1952) Humidification of the air passages. Thorax 7(2):148–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19. 11 March 2020

- 4.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019.Accessed 12th august 2020

- 5.https://www.mohfw.gov.in/ accessed 13th august 2020

- 6.Scarano A, Inchingolo F, Lorusso F (2020) Facial skin temperature and discomfort when wearing protective face masks: thermal infrared imaging evaluation and hands moving the mask. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(13): 4624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Roberge RJ, Kim JH, Benson SM. Absence of consequential changes in physiological, thermal and subjective responses from wearing a surgical mask. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2012;181(1):29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang L, Yin H, Di Y, Liu Y, Liu J. Human local and total heat losses in different temperature. Physiol Behav. 2016;157:270–276. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DuBois AB, Harb ZF, Fox SH. Thermal discomfort of respiratory protective devices. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1990;51(10):550–554. doi: 10.1080/15298669091370086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y, Tokura H, Guo Y, et al. Effects of wearing N95 and surgical facemask on heart rate, thermal stress and subjective sensations. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2005;78:501–509. doi: 10.1007/s00420-004-0584-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naftali S, Rosenfeld M, Wolf M, et al. The Air-Conditioning Capacity of the Human Nose. Ann Biomed Eng. 2005;33:545–553. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-2513-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varene P, Ferrus L, Manier G, et al. Heat and water respiratory exchanges: comparison between mouth and nose breathing in humans. Clin Physiol. 1986;6:405–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097X.1986.tb00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desai SR, Kovarik C, Brod B, et al (2020) COVID-19 and personal protective equipment Treatment and prevention of skin conditions related to the occupational use of personal protective equipment. J Am Acad Dermatol 83(2):675–677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Foo CC, Goon AT, Leow YH, Goh CL. Adverse skin reactions to personal protective equipment against severe acute respiratory syndrome: a descriptive study in Singapore. Contact dermatitis. 2006;55:291–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2006.00953.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zuo Y, Hua W, Luo Y, Li L. Skin reactions of N 95 masks and medical masks among healthcare personnel: a self report questionnaire survey in China. Contact dermatitis 2020 Apr 16 [ epub ahead of print ]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Yan Y, Chen H, Chen L, Chen B, Diao P, Dong L, et al. Consensus of Chinese experts on protection of skin and mucous membrane barrier for health-care workers fighting against coronavirus disease 2019. Dermatol Ther. 2020;2020:e13310. doi: 10.1111/dth.13310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]