Abstract

Background

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory airway disease that usually causes variable airway obstruction. It affects 5–10% of the German population.

Methods

This review is based on relevant publications retrieved by a selective search, as well as on national and international guidelines on the treatment of mild and moderate asthma in adults.

Results

The goal of treatment is to attain optimal asthma control with a minimal risk of exacerbations and mortality, loss of pulmonary function, and drug side effects. This can be achieved with a combination of pharmacotherapy and non-drug treatment including patient education, exercise, smoking cessation, and rehabilitation. Pharmacohterapy is based on inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and bronchodilators. It is recommended that mild asthma should be treated only when needed, either with a fixed combination of ICS and formoterol or with short-acting bronchodilators. For moderate asthma, maintenance treatment is recommended, with an inhaled fixed combinations of ICS and long-acting beta-mimetics, possibly supplemented with long-acting anticholinergic agents. Allergen immunotherapy, i.e., desensitization treatment, should be considered if the allergic component of asthma is well documented and the patient is not suffering from uncontrolled asthma. Asthma control should be monitored at regular intervals, and the treatment should be adapted accordingly.

Conclusion

The treatment of asthma in adults should be individually tailored, with anti-inflammatory treatment as its main component.

Asthma is a heterogeneous disease characterized by chronic inflammation of the airways and in most cases variable degrees of airway obstruction; it affects around 5% of the world’s population (1, 2). The prevalence of asthma increased markedly during the 20th century and now appears to have leveled off (3). In Germany, the lifetime prevalence of asthma is 8.6% (4). In patients with asthma, periods with no symptoms can alternate with symptomatic periods of variable severity. Clinically, the picture is dominated by recurrent episodes of chest tightness, shortness of breath, and characteristic stridor and/or coughing, especially at night and in the early morning. The symptoms of asthma usually regress either spontaneously or after appropriate treatment. Acute worsening of the disease in the form of asthma attacks or exacerbations can occur at any moment without warning and can be life-threatening (5). The information contained in this article is based on analysis of the evidence, recommendations in current national (6, 7) and international guidelines (5), and a selective literature search of PubMed, and applies to adult patients with asthma.

Prevalence of asthma.

In Germany, the lifetime prevalence of asthma is 8.6%.

Forms of asthma.

Allergic asthma often starts during childhood or adolescence, whereas intrinsic asthma (asthma without evidence of allergy) usually starts during adulthood.

Learning goals

After studying this article, the reader should:

Be familiar with current concepts in the diagnosis and treatment of asthma;

Be able to list the pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatment options for asthma;

Understand how to carry out and manage inhalation therapy in patients with asthma.

Guidelines

The international recommendations for the treatment of asthma are updated every year by the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) and are freely available on the internet (www.ginasthma.com) (5). The clinical guideline issued by the German-language medical societies was last updated in 2017 (7) and the National Disease Management Guideline for Asthma (Nationale Versorgungsleitlinie [NVL] Asthma) was updated in 2020 (7).

Types of asthma and biomarkers

Types of asthma and biomarkers.

In adults, two common types of asthma are distinguished: allergic asthma, where there is a clear relationship to allergy, and intrinsic or eosinophilic asthma, which usually starts in adulthood without evidence of any relevant allergies.

In adults, two common types of asthma are distinguished. The first is allergic asthma, where there is a clear relationship with allergy. Onset is often during childhood or adolescence and often accompanied by allergic rhinitis and/or atopic dermatitis; this form is known as “early-onset asthma.” The second is an intrinsic (eosinophilic) type, usually with onset in adulthood and usually without evidence of any relevant allergies; this form is referred to as “adult-onset” or “late-onset asthma”) (8). In both types of asthma, an increased level of typical cytokines and eosinophil granulocytes is found, together with dysfunction of structural cells (including bronchial epithelial cells, which release increased amounts of nitric oxide [NO]) (9)—characteristics referred to collectively under the name “type 2 asthma” (10). The inflammation can be measured through biomarkers (box 1). Routine diagnostic procedures covered by statutory health insurance carriers in Germany include blood eosinophil count and allergy markers; fractional exhaled NO (FeNO) measurement is available as a self-pay option. It should be noted that these biomarkers can be “falsified”: for example, eosinophil counts can be greatly reduced by inhaled or oral steroids (11) and FeNO levels by tobacco smoke (12).

BOX 1. Biomarkers in asthma *.

Increase in eosinophils (≥150 cell/µL blood or ≥2% in sputum)

and/or

Increased exhalation of nitric oxide: increased fraction of exhaled NO, FeNO, measured in parts per billion (≥ 20 ppb)

and/or

Indicators of an allergic etiology (positive history, typical comorbidities, positive skin prick test, presence of allergen-specific IgE)

*Recommended threshold values according to the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) 2019 (37)

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of asthma rests on four pillars (box 2), of which careful history taking is the most important. Since 39.25% of asthma patients in Europe are smokers (1), to rule out chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) it is particularly helpful to ask questions about variability of symptoms over time (in COPD there is little variability), nighttime symptoms (usually absent in COPD), and whether symptoms respond well to steroids (in COPD this is rarely the case). Asthma is a clinical diagnosis that can only be made by considering all the findings together.

BOX 2. Diagnosis of asthma.

-

Detailed history

Typical symptoms, typical triggers, and typical disease course; also, if applicable, typical response to steroid therapy

-

Lung function test (bodyplethysmography or spirometry)

Evidence of at least partially reversible airway obstruction and/or bronchial hyperresponsiveness

-

Allergy-related investigation

Specifically allergy-related history plus skin prick test or measurement of specific serum IgE; total serum IgE; allergen provocation test if appropriate

-

Biomarker measurement

Evidence of increased eosinophils in blood and/or raised FeNO (see Box 1)

Treatment goals

Diagnosis.

Asthma is a clinical diagnosis that can only be made by considering all the findings together. A careful history is the most important part of asthma diagnosis.

GINA defines the goals of treatment for asthma as follows (5):

Achieving the best possible asthma control;

Minimizing the risk of exacerbations and death, loss of lung function, and adverse medication effects.

In addition, the patient’s individual treatment goals should be taken into account. To achieve these goals, the use of nonpharmacological strategies and the most effective pharmacological interventions with fewest adverse effects is recommended.

Asthma control and severity of asthma

The key goal of treatment is good asthma control, and for this reason considerable importance attaches to measuring asthma control in the everyday clinical setting. Asthma control is classified into three grades:

Controlled asthma

Partly controlled asthma

Uncontrolled asthma.

Asthma control.

Asthma control is the basis of short-term (relief) and long-term (maintenance) treatment.

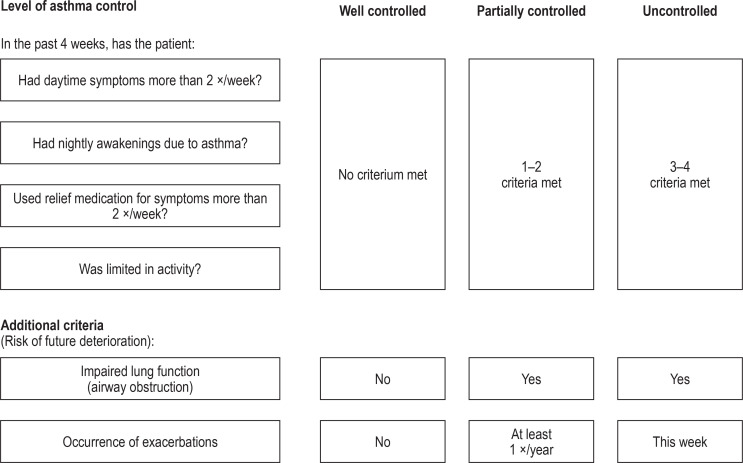

The level of asthma control should be monitored at regular intervals (e.g., every 3 months) in order to determine whether treatment needs to be stepped up (13). According to GINA (5) and the National Disease Management Guidelines (7), four questions suffice to determine the level of asthma control; in addition, restriction of lung function and the number of exacerbations should be taken into account (figure 1). Alternatively, the Asthma Control Test (ACT, which contains five questions) can be used to measure asthma control (13). The asthma severity level is defined according to the response to treatment (box 3) (6, 14).

Figure 1.

Level of asthma control according to the German National Disease Management Guideline 2020 (7)

To measure the level of asthma control, the National Disease Management Guideline 2020 (7), following the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA), recommends asking the patient four questions. Lung function should also be tested to check for airway obstruction, and the patient should be asked about any exacerbations that have occurred (these additional criteria help assessment of the risk that asthma control will deteriorate in the future). Modified from (7).

BOX 3. Levels of asthma severity*1.

-

Mild asthma

Asthma well controlled by step 1 or 2 therapy*2

-

Moderate asthma

Asthma well controlled by step 3 or 4 therapy

-

Severe asthma

Asthma not well controlled by maximum inhaled therapy, or asthma control lost when this therapy is reduced; step 5 therapy required

*1 Modified from (6). *2 Treatment steps for asthma management according to the German National Disease Management Guideline for Asthma

Principles of asthma treatment

Treatment goal.

The goal is to achieve and maintain asthma control by suppressing the asthmatic inflammation with a minimum of drugs at the lowest possible dose.

Asthma is a disease that is primarily managed in the outpatient setting; inpatient treatment is rarely needed. Both nonpharmacological strategies (box 4) and pharmacological treatment are available for the management of asthma, mostly with a strong evidence base (7). According to a metaanalysis by Bateman et al. (64 RCTs, 42 527 patients), however, only drug regimens containing inhaled steroids (ICS) improve patients’ quality of life (15). During a patient’s consultation with the physician, the treatment goal is defined taking account of the patient’s individual life circumstances and preferences. Recommendations for treatment need to take into account the variable severity as well as the intra-individual variability of the disease over time, with treatment being adjusted on the basis of the level of asthma control. Often, treatment plans are a compromise between the physician’s recommendations for treatment and the patient’s willingness to adhere to the treatment. Using the step approach, treatment can be stepped up and down:

BOX 4. Nonpharmacological strategies in asthma (7).

-

The National Disease Management Guideline for Asthma (7) gives a strong positive recommendation for the following:

Asthma education

A written asthma action plan

Rehabilitation

Regular physical exercise

Breathing exercises

Smoking cessation/avoidance of passive smoke exposure

Optimization of body weight

Avoidance of allergens

Elimination of damp and mould in indoor environments

Principles of treatment.

Asthma is treated by both pharmacological and nonpharmacological means.

Long-term therapy.

Long-term treatment with an anti-inflammatory drug is recommended as soon as an as-needed reliever drug is in use >2×/week.

When asthma is either uncontrolled or only partly controlled, treatment should be stepped up until good control is achieved.

When asthma has been well controlled for at least 3 months, treatment can be stepped down. In patients with only seasonal symptoms, treatment may be governed by allergen exposure at the time, so that a step down may be possible even after quite a short treatment period. It is recommended that, after each step up or down, asthma control should be checked again after 3 months.

The goal is maintenance of good asthma control with the least possible number of drugs at the lowest possible dosage.

Theophylline preparations no longer play a role in long-term treatment, because of their narrow therapeutic range, their potential adverse effects, and the existence of more effective alternatives (16). Antitussives and mucoregulators are not indicated; the cough symptoms typical of asthma can usually be controlled by anti-inflammatory agents and bronchodilators (7).

Paradigm shift in the treatment of mild asthma

Asthma and the workplace.

Potential asthma triggers associated with the workplace should be identified and eliminated. In some cases, a change of workplace or occupation may be unavoidable.

Hitherto, for treatment at step 1 (symptoms at most twice a week), purely “as-needed” relief treatment with short-acting inhaled β2-agonists (SABAs) was recommended. At stage 2 (SABAs needed more than twice a week, but not daily), a long-term low-dose ICS plus a SABA as needed was recommended. Both these recommendations were controversial, because:

β2-Agonist monotherapy in asthma increases bronchial hyperresponsiveness and mortality (and is therefore contraindicated for long-term treatment) (17).

Patients often use maintenance ICS treatment irregularly or in an on/off manner (18).

Fixed-dose ICS+LABA combinations offer many advantages (box 5). Because of their rapid bronchodilatory effect (similar to that achieved with salbutamol), ICS+LABA fixed-dose combinations containing formoterol can also be used for rapid relief. To date, fixed-dose ICS+formoterol combinations are only approved in Europe as an as-needed inhaled add-on to ICS+formoterol long-term treatment (19).

BOX 5. Advantages of ICS+LABA fixed-dose combination therapy.

-

Safety

-

Efficacy

ICS+LABA fixed-dose combinations are more effective than corresponding ICS monotherapies. A metaanalysis by Ducharme et al. (77 randomized controlled studies, 21 248 patients) showed a 23% reduction in exacerbation rate (95% confidence interval: [13;32]), a mean improvement in lung function of 110 mL [90; 130], and an 11.88% increase in the number of symptom-free days [8.25: 15.50] with ICS+LABA fixed-dose combination therapy compared to ICS monotherapy (39).

-

Reduced ICS exposure

Because of pharmacological synergies between ICS and LABA, the ICS requirement and hence ICS exposure are reduced (40).

-

Adherence to treatment

ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting β2-agonist

However, studies have shown that purely as-needed treatment with ICS+formoterol is not inferior to existing treatment options at steps 1 and 2 (SABA as needed; low-dose ICS maintenance treatment plus SABA) in terms of the course over time of lung function, and in terms of reduction of severe exacerbations it is even superior (20– 22). Table 1 shows the results of the Novel-START study, a randomized study carried out under everyday clinical conditions (21). Moreover, with purely as-needed ICS+formoterol therapy, ICS exposure is 50 to 83% lower than with ICS maintenance therapy (20– 22). Thus, for mild asthma, purely as-needed ICS+formoterol therapy is the safest strategy, with the fewest adverse effects. GINA therefore recommends low-dose as-needed ICS+formoterol therapy as the preferred option at step 1 and as an equivalent alternative to ICS maintenance therapy at step 2 (18).

Table 1. Effect of ICS+formoterol as-needed therapy*1.

| Patients at step 1 or 2 | Compared with SABA as-needed therapy | Compared with ICS maintenance therapy |

| Lung function (FEV1) |

+ 30 mL 95% CI: [6; 70 mL] |

+ 4 mL 95% CI: [–30; 40 mL] |

| All exacerbations | RR 0.49*2 95% CI: [0.33; 0.72] |

RR 1.12 95% CI: [0.70; 1.79] |

| Severe exacerbations | RR 0.40*2 95% CI: [0.18; 0.86] |

RR 0.44*2 95% CI: [0.20; 0.96]) |

*1 In the open (nonmasked) Novel-START study, 668 patients with asthma at step 1 or step 2 (“mild asthma”) were randomized into three treatment arms:

1) Salbutamol only, as needed,

2) Maintenance ICS (2 × 200 µg budesonide by Turbuhaler daily) plus salbutamol as needed, or

3) ICS+formoterol as needed (by inhalation of a fixed-dose combination of 200 µg budesonide and 6 µg formoterol as needed).

The table shows changes in forced expiratory pressure (FEV1) and risk reduction (RR) for the occurrence of exacerbations after 52 weeks of ICS+formoterol as-needed treatment in comparison with the other two treatment arms. Severe exacerbations were defined by the need to use systemic corticosteroids. ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; CI, confidence interval; SABA, short-acting inhaled β2 -agonist

*2 p <0.001

As of April 2020, the use of ICS+formoterol on a solely as-needed basis for asthma has not been formally approved in Europe, but the reality is that this purely as-needed regimen is already in use by many patients.

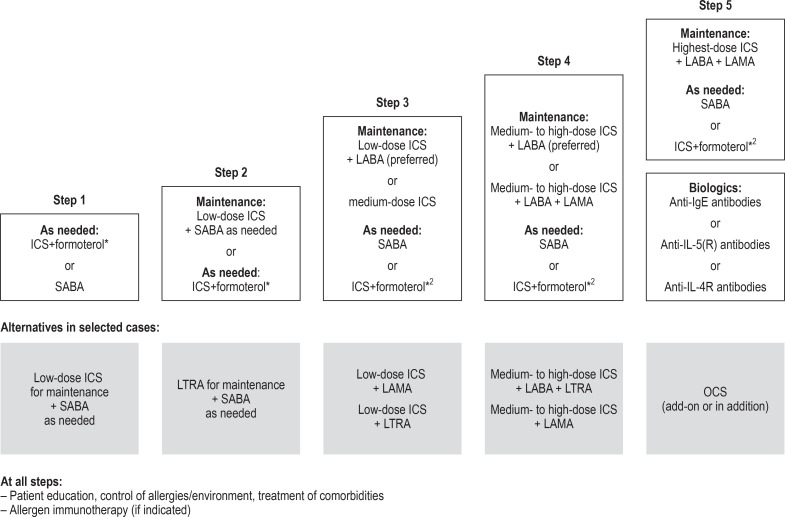

Stepwise approach to asthma treatment in adults

Current national and international asthma guidelines recommend a five-step approach to treatment (7). Treatment is based on regular patient education, checking the patient’s inhaler technique, reducing asthma triggers (e.g., allergen exposure or smoking), and treatment of comorbidities (figure 2) (7). Potential workplace-related asthma triggers should be identified and eliminated; in some cases a change of workplace or occupation may be unavoidable (23).

Figure 2.

Stepped approach to pharmacological therapy according to the German National Disease Management Guideline (Nationale Versorgungsleitlinie) 2020 (7)

Following GINA, the German National Disease Management Guideline recommends a five-step approach to treatment. Depending on the level of asthma control, medications are stepped up or down until good asthma control is achieved with as few medications as possible at the lowest possible dosage.

Modified from (7).

*1 Fixed-dose combination (low-dose ICS + formoterol) on an as-needed basis is not approved for steps 1 and 2 (as of February 2020)

*2 ICS+formoterol as needed if this combination is also used for maintenance therapy

GINA, Global Initiative for Asthma; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting β2-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist;

LTRA, leukotriene receptor antagonist; OCS, oral glucocorticosteroid; SABA, short-acting inhaled β2-agonist

Allergen immunotherapy

Theophylline preparations.

Because of their narrow therapeutic spectrum, their potential adverse effects, and the existence of more effective alternatives, theophylline preparations no longer have a place in the long-term treatment of asthma.

Allergen immunotherapy.

Allergen immunotherapy may be considered in any patient with mild to moderate allergic asthma in whom there is a clear relationship between respiratory symptoms and allergen exposure.

Contraindication to allergen immunotherapy.

Uncontrolled asthma is a contraindication to allergen immunotherapy.

Subcutaneous or sublingual allergen immunotherapy (AIT, previously known as hyposensitization or specific immunotherapy) (24) may be considered at any treatment step in patients with allergic asthma, provided the allergic components of the asthmatic symptoms are well documented (proven specific sensitization and clear clinical symptoms after allergen exposure) and the criteria specified in the summary of product characteristics are fulfilled (figure 2) (recommendation grade A, strong positive recommendation) (7). Uncontrolled asthma is a contraindication to AIT. AIT is not a substitute for adequate inhalation therapy, which must be continued during AIT. Within the provisions of the German therapy allergens ordinance (Therapieallergene-Verordnung), the efficacy of AIT preparations must be proven in placebo-controlled studies. A regularly updated list of preparations with evidence of their efficacy is available on the website of the German Society of Allergology and Clinical Immunology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allergologie und klinische Immunologie) (25). Decisions regarding indications, selection of allergens, modes of administration, and the carrying out and management of AIT require specialist expertise and should therefore if possible be carried out by qualified allergists.

Initial treatment

In previously untreated patients who meet the criteria for partly controlled asthma, long-term therapy should start at step 2; in those whose asthma is uncontrolled it should start at step 3 at the lowest (recommendation grade B, weak positive recommendation) (6, 7).

Steps 1 and 2

Mild asthma.

At step 1, either ICS+formoterol as needed or a SABA as needed is recommended. At step 2, either ICS+formoterol as needed or a long-term low-dose ICS is recommended.

At step 1, either ICS+formoterol as needed or SABA as needed is recommended (5, 21– 23) (figure 2). From step 2 at the latest, treatment with an ICS is recommended as these medications reduce the inflammation and hyperresponsiveness of the airways, result in improved asthma control and quality of life, and reduce the risk of exacerbations and life-threatening asthma attacks (26). At step 2, either low-dose long-term ICS or purely as-needed ICS+formoterol may be used. A less effective alternative is the leukotriene receptor antagonist montelukast (27), which can be used in patients who refuse ICS treatment or are unable to tolerate it, e.g., because of local adverse effects. If symptoms occur only on physical exercise (“exercise-induced asthma”), inhaling a SABA before physical effort is still recommended (28). Patients with asthma often avoid physical activity for fear of inducing symptoms. However, physical activity has many positive effects on the disease itself and on potential concomitant conditions, so regular physical activity (combined with medication) should be expressly recommended (recommendation grade A, strong positive recommendation) (5, 29). Pregnant women with asthma often reduce their inhalation therapy for fear of adverse effects on the fetus (30). However, all guidelines make strong recommendations for consistently adhering to ICS or ICS+LABA therapy during pregnancy, since the risks associated with loss of asthma control or exacerbations far outweigh the potential risk of medication adverse effects (for which no evidence exists at present) (5– 7).

Step 3

From step 3 onwards, regular long-term maintenance treatment is recommended (figure 2), either

With a fixed-dose combination of a low-dose ICS with a long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) with additional use of a SABA as needed for quick relief, or else

With a fixed-dose combination of a low-dose ICS with formoterol (ICS+formoterol) used for both maintenance and as-needed relief (“single-inhaler maintenance and reliever therapy” [SMART]) (19).

Alternatively, at step 3 ICS monotherapy at an intermediate dose can be started: a fixed-dose combination of low-dose ICS and LABA is, however, preferable because it is better tolerated and is more effective (26). In cases where LABA is contraindicated or the patient suffers adverse effects to LABA therapy (box 6), a combination of low-dose ICS and a long-acting anticholinergic (long-acting antimuscarinic receptor antagonist, LAMA), or a combination of low-dose ICS and montelukast can be used. LAMAs (such as tiotropium) are not approved for use for this indication, so the rationale for its use needs to be demonstrated (31, 32). Neither LABA or LAMA should be given as monotherapy in asthma, and neither should a combination consisting exclusively of LABA+LAMA (7).

BOX 6. Typical potential adverse effects of inhalants (>1% of treated patients).

-

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS)

Hoarseness, sore throat, oral thrush

-

Long-acting β2-agonists (LABA)

Tremor, palpitations, muscle cramps

-

Long-acting anticholinergics (LAMA)

Dry mouth, urinary retention/dysuria, constipation

Steps 4 and 5

Moderate asthma.

From step 3 onward, long-term treatment with fixed-dose combinations of ICS and a long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) is recommended.

Anticholinergics.

To improve asthma control and lung function and reduce the exacerbation rate and ICS requirement, long-acting anticholinergics (LAMAs) may be added to ICS+LABA treatment.

Increasing ICS to high-dose or highest-dose.

Increasing the ICS dose to high or highest can result in greatly improved asthma control in patients with severe forms of asthma, but the risk of local and systemic adverse effects also increases.

From step 4 onwards, the preferred option is an ICS+LABA fixed-dose combination with the ICS at an intermediate or high dose, and from step 5 on the ICS should be at the highest dose (figure 2). The National Disease Management Guideline for Asthma defines four ICS dose levels (table 2) (7). The risk–benefit ratio is most favorable in the low-dose range (26). Raising the ICS dose to high or highest can result in better asthma control in patients with severe forms of asthma, but increases the risk of local (box 6) and systemic adverse effects (e.g., osteoporosis, diabetes, cataract, suppression of adrenal function) (26). A highest dose of ICS can equate to a dose of 2 to 5 mg prednisolone-equivalent per day (33). For this reason, regular follow-up (e.g., every 3 months) is required to check whether highest-dose ICS therapy continues to be necessary. From step 4 onward, to improve asthma control and lung function and reduce the exacerbation rate and ICS requirement, a LAMA can be added, either as a separate inhaler (to date only tiotropium under the name Respimat is approved for this use) or as triple therapy in a single inhaler (ICS+LABA+LAMA; not currently approved as a treatment for asthma) (34). Two phase-III studies have shown an increase in lung function by 57 to 73 mL and reduction in exacerbations by 12–15% with triple therapy (ICS+LABA+LAMA) compared to ICS+LABA therapy (34). According to the National Disease Management Guideline, at step 5, before further therapy options are investigated, highest-dose ICS therapy in combination with a LABA or LAMA should be tried for at least 3 months (figure 2). If it is not possible to achieve good asthma control under this regimen, or exacerbations continue to occur, the use of highly potent biologics (table 3) should be considered (9). To avoid severe adverse effects, long-term therapy with systemic glucocorticoids should be given only in carefully selected individual cases (7).

Table 2. Dosage of inhaled corticosteroids according to the German National Disease Management Guideline 2020 (7).

| Active ingredient (ICS) | Daily dose (μg) | |||

| Low dose | Moderate dose | High dose | Highest dose | |

| Beclomethasone dipropionate (BDP) inhaled powder | 200–500 | >500–1000 | >1000 | ≥2000 |

| Beclomethasone dipropionate (BDP) metered-dose aerosol | 100–200 | >200–400 | >400 | ≥1000 |

| Budesonide | 200–400 | >400–800 | >800 | ≥1600 |

| Ciclesonide | 80 | 160 | ≥320 | ≥320 |

| Fluticasone furoate | 100 | – | 200 | 200 |

| Fluticasone propionate | 100–250 | >250–500 | >500 | ≥1000 |

| Mometasone furoate | 200 | 400 | >400 | ≥800 |

The table shows daily total doses of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) according to the German National Disease Management Guideline (7).

The doses declared on the inhalers can sometimes differ from those used to calculate the total dose. For example, for the budesonide+formoterol fixed combination, the dose declared is the one that leaves the mouthpiece (at the highest dose this is 320 µg per inhalation), whereas the one used to calculate the total dose is the dose measured off in the inhaler (400 µg budesonide). With the beclomethasone/formoterol (metered-dose aerosol), a dose of 100 µg beclomethasone is declared, but because the aerosol is extrafine, this corresponds to a dose of 250 µg beclomethasone when given as a less fine aerosol, and the latter is the dose fed into the dose calculation.

Table 3. Biologic agents in the treatment of severe asthma.

| Biologic class |

Biologic agent (administration schedule) |

Approved for use | Approved for self-administration |

| Anti-IgE |

Omalizumab (every 2–4 weeks s.c.) |

From age 6 | Yes |

| Anti-IL-5 |

Mepolizumab (every 4 weeks s.c.) |

From age 6 | Yes |

| Anti-IL-5 |

Reslizumab (every 4 weeks i.v.) |

From age 18 | No |

| Anti-IL-5-(R) |

Benralizumab (every 8 weeks s.c.) |

From age 18 | Yes |

| Anti-IL-4/13 |

Dupilumab (every 2 weeks s.c.) |

From age 12 | Yes |

The table shows the currently approved biologic agents, which may be classified in three different classes. The patient age from which they are approved for use is also given. Almost all these biologics are approved for self-administration. s.c., subcutaneously

Inhaler technique and inhaler systems

The great majority of patients with asthma can achieve good asthma control solely through the use of highly effective inhalants (5). This requires, however, that the right type of inhaler is chosen for each individual patient and the patient carefully instructed in the technique for using it. More than 20% of patients make critical errors in their inhaler technique and thus remain to all intents and purposes untreated (35). In choosing an inhaler system, patients’ individual abilities and preferences need to be taken into account. Metered-dose aerosol inhalers and Respimat require the patient to be able to coordinate release of the drug with inspiration; dry powder inhalers, on the other hand, require sufficient sucking strength to release the drug from the inhaler (36). Adding a spacer can improve bronchial deposition of metered-dose aerosols, so the use of a spacer should be especially considered in patients with severe asthma or those experiencing local adverse effects. As a matter of principle, every patient should be prescribed only one inhalation system, since it is too confusing for patients to have to cope with different techniques for different inhalers (36), and when the physician has trained a patient on one inhaler, the pharmacy should not be permitted to change it. To support patient training in inhaler technique, 2- to 3-min instruction videos on the use of every inhaler are available free on the website of the German Airways League (Deutsche Atemwegsliga; www.atemwegsliga.de).

Adjusting treatment.

To ensure correct adjustment of treatment, asthma control should be checked every 3 months.

Inhaler.

For inhalation therapy for asthma to be effective, the right choice of inhaler must be made together with the patient and the patient carefully instructed in the technique for using it.

Further information on CME.

-

Participation in the CME certification program is possible only over the Internet: cme.aerzteblatt.de.

This unit can be accessed until 18. 6. 2021.

Submissions by letter, e-mail, or fax cannot be considered.

Once a new CME module comes online, it remains available for 12 months. Results can be accessed 4 weeks after you start work on a module. Please note the closing date for each module, which can be found at cme.aerzteblatt.de

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Continuing Medical Education. Participants in the CME program can manage their CME points with their 15-digit “uniform CME number” (einheitliche Fortbildungsnummer, EFN), which is found on the CME card (8027XXXXXXXXXXX). The EFN must be stated during registration on www.aerzteblatt.de (“Mein DÄ”) or else entered in “Meine Daten,” and the participant must agree to communication of the results.

CME credit for this unit can be obtained via cme.aerzteblatt.de until 18 June 2021. Only one answer is possible per question. Please select the answer that is most appropriate.

Question 1

Which of the following parameters is best suited to guide asthma treatment?

Lung function

Asthma control

Severity

Frequency of exacerbations

Self-reported symptom burden

Question 2

Which of the following is recommended by the German National Disease Management Guideline as the preferred option to treat asthma at step 1?

ICS monotherapy

Maintenance ICS

Low-dose ICS+formoterol as needed

Biologics

SABA as needed

Question 3

Which of the following is a risk factor for future worsening of asthma?

Good adherence to treatment

Light physical activity

Normal body weight

Exposure to tobacco smoke

Positive family history

Question 4

Which class of drug is the basis of long-term maintenance treatment for asthma?

Long-acting β2-agonists

Long-acting anticholinergics

Theophylline

Inhaled corticosteroids

Systemic corticosteroids

Question 5

Which class of drugs is recommended as an adjunct to ICS+LABA therapy from step 4 onward?

Methylxanthine

Systemic corticosteroids

Antitussives

Mucolytics

Long-acting anticholinergics (LAMAs)

Question 6

Which drugs should be given as maintenance treatment from step 3 onward?

Low-dose ICS + LABA

Cromone + anti-IgE antibodies

Systemic corticosteroids + oral glucocorticosteroids

Montelukast + SABA

Antihistaminines + highest-dose LABA

Question 7

With nonseasonal asthma, for how long should asthma control be stable before an attempt is made to step down treatment?

One week

Four weeks

Three months

Six months

One year

Question 8

What is a typical nonmedication strategy for asthma?

Sleep training

Smoking cessation

Mindfulness training

Nutritional advice

Lung volume reduction

Question 9

Which biologic is approved for treatment of severe asthma in patients aged 18 years or over and is given every 8 weeks subcutaneously?

Benralizumab

Rituximab

Omalizumab

Mepolizumab

Dupilumab

Question 10

Which of these is a typical potential adverse effect of long-acting anticholinergics?

Hoarseness

Sore throat

Oral thrush

Tremor

Dry mouth

► Participation is only possible via the Internet: cme.aerzteblatt.de

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Kersti Wagstaff.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Professor Lommatzsch has received lecture and consultancy fees from ALK, Allergopharma, Astra Zeneca, Bencard, Berlin-Chemie, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bosch, Chiesi, Circassia, GSK, HAL Allergy, Janssen-Cilag, MSD, Mundipharma, Novartis, Nycomed/Takeda, Sanofi, TEVA, and UCB. He has received reimbursement of attendance fees for conferences and educational events, and of travel and accommodation costs from Novartis and AstraZeneca. He has received research support from DFG, GSK, and AstraZeneca. He has received funding for performing clinical studies from AstraZeneca and Sanofi.

Dr. Korn has received lecture and consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bosch, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Sanofi, TEVA, and UCB. She has received reimbursement of attendance fees for conferences and educational events, and of travel and accommodation costs from Novartis and AstraZeneca. She has received research support and funding for performing clinical studies from DFG, Astra Zeneca, Bosch, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi. She has received funding for performing clinical studies from Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi.

Professor Buhl has received lecture and consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Berlin Chemie, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Sanofi. He has received reimbursement of attendance fees for conferences and educational events, and of travel and accommodation costs from AstraZeneca, Berlin Chemie, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Sanofi, as well as research support at the University of Mainz as part of personally initiated projects and clinical studies from DFG, AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bosch, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi.

References

- 1.To T, Stanojevic S, Moores G, et al. Global asthma prevalence in adults: findings from the cross-sectional world health survey. BMC public health. 2012;12 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability-adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5:691–706. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30293-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sears MR. Trends in the prevalence of asthma. Chest. 2014;145:219–225. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langen U, Schmitz R, Steppuhn H. Häufigkeit allergischer Erkrankungen in Deutschland. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2013;56:698–706. doi: 10.1007/s00103-012-1652-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. www.ginasthma.org, Update 2019, (last accessed on 14 April 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buhl R, Bals R, Baur X, et al. Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of asthma - guideline of the German Respiratory Society and the German Atemwegsliga in cooperation with the Paediatric Respiratory Society and the Austrian Society of Pneumology. Pneumologie. 2017;71:849–919. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-119504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nationale Versorgungsleitlinie (NVL) Asthma. www.leitlinien.de/nvl/asthma 2020; 4. Auflage, AWMF-Register-Nr.: nvl-002. (last accessed on 14 April 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pavord ID, Beasley R, Agusti A, et al. After asthma: redefining airways diseases. Lancet. 2018;391:350–400. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30879-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lommatzsch M. Immune-modulation in asthma: current concepts and future strategies. Respiration. 2020 doi: 10.1159/000506651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lambrecht BN, Hammad H, Fahy JV. The cytokines of asthma. Immunity. 2019;50:975–991. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lommatzsch M, Klein M, Stoll P, Virchow JC. Impact of an increase in the inhaled corticosteroid dose on blood eosinophils in asthma. Thorax. 2019;74:417–418. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-212233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dweik RA, Boggs PB, Erzurum SC, et al. An official ATS clinical practice guideline: interpretation of exhaled nitric oxide levels (FENO) for clinical applications. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:602–615. doi: 10.1164/rccm.9120-11ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O‘Byrne PM, Reddel HK, Eriksson G, et al. Measuring asthma control: a comparison of three classification systems. Eur Respir J. 2010;36:269–276. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00124009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lommatzsch M, Virchow JC. Severe asthma: definition, diagnosis and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111:847–855. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bateman ED, Esser D, Chirila C, et al. Magnitude of effect of asthma treatments on Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire and Asthma Control Questionnaire scores: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:914–922. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah L, Wilson AJ, Gibson PG, Coughlan J. Long acting beta-agonists versus theophylline for maintenance treatment of asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001281. Cd001281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nwaru BI, Ekstrom M, Hasvold P, Wiklund F, Telg G, Janson C. Overuse of short-acting beta2-agonists in asthma is associated with increased risk of exacerbation and mortality: A nationwide cohort study of the global SABINA programme. Eur Respir J. 2020 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01872-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reddel HK, FitzGerald JM, Bateman ED, et al. GINA 2019: a fundamental change in asthma management: Treatment of asthma with short-acting bronchodilators alone is no longer recommended for adults and adolescents. Eur Respir J. 2019 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01046-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sobieraj DM, Weeda ER, Nguyen E, et al. Association of inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta-agonists as controller and quick relief therapy with exacerbations and symptom control in persistent asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama. 2018;319:1485–1496. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O‘Byrne PM, FitzGerald JM, Bateman ED, et al. Inhaled combined budesonide-formoterol as needed in mild asthma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1865–1876. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1715274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beasley R, Holliday M, Reddel HK, et al. Controlled trial of budesonide-formoterol as needed for mild asthma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2020–2030. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1901963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hardy J, Baggott C, Fingleton J, et al. Budesonide-formoterol reliever therapy versus maintenance budesonide plus terbutaline reliever therapy in adults with mild to moderate asthma (PRACTICAL): a 52-week, open-label, multicentre, superiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394:919–928. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31948-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henneberger PK, Patel JR, de Groene GJ, et al. Workplace interventions for treatment of occupational asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;10 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006308.pub4. Cd006308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfaar O, Agache I, de Blay F, et al. Perspectives in allergen immunotherapy: 2019 and beyond. Allergy. 2019;74:3–25. doi: 10.1111/all.14077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liste der AIT-Präparate mit Wirksamkeitsnachweis, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allergologie und klinische Immunologie (DGAKI) www.dgaki.de/leitlinien/s2k-leitlinie-sit/sit-produkte-studien-zulassung/(last accessed on 14 April 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beasley R, Harper J, Bird G, Maijers I, Weatherall M, Pavord ID. Inhaled corticosteroid therapy in adult asthma Time for a new therapeutic dose terminology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199:1471–1477. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201810-1868CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chauhan BF, Ducharme FM. Addition to inhaled corticosteroids of long-acting beta2-agonists versus anti-leukotrienes for chronic asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003137.pub5. Cd003137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiler JM, Brannan JD, Randolph CC, et al. Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction update-2016. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:1292–1295e36. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carson KV, Chandratilleke MG, Picot J, Brinn MP, Esterman AJ, Smith BJ. Physical training for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001116.pub4. Cd001116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robijn AL, Jensen ME, McLaughlin K, Gibson PG, Murphy VE. Inhaled corticosteroid use during pregnancy among women with asthma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2019;49:1403–1417. doi: 10.1111/cea.13474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buhl R, FitzGerald JM, Busse WW. Tiotropium add-on to inhaled corticosteroids versus addition of long-acting beta2-agonists for adults with asthma. Respir Med. 2018;143:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2018.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang L, Zhou R, Xie X. Tiotropium added to low- to medium-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) versus low- to medium-dose ICS alone for adults with mild to moderate uncontrolled persistent asthma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Asthma. 2019;56:69–78. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2018.1424192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maijers I, Kearns N, Harper J, Weatherall M, Beasley R. Oral steroid-sparing effect of high-dose inhaled corticosteroids in asthma. Eur Respir J. 2020;55 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01147-2019. 1901147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Virchow JC, Kuna P, Paggiaro P, et al. Single inhaler extrafine triple therapy in uncontrolled asthma (TRIMARAN and TRIGGER): two double-blind, parallel-group, randomised, controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2019;394:1737–1749. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Usmani OS, Lavorini F, Marshall J, et al. Critical inhaler errors in asthma and COPD: a systematic review of impact on health outcomes. Respir Res. 2018;19 doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0710-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Usmani OS. Choosing the right inhaler for your asthma or COPD patient. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2019;15:461–472. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S160365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) Difficult-to-treat and severe asthma in adolescents and adult patients: diagnosis and management. www.ginasthma.org April 2019; Version 2.0 (last accessed on 14 April 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Busse WW, Bateman ED, Caplan AL, et al. Combined analysis of asthma safety trials of long-acting beta2-agonists. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2497–2505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ducharme FM, Ni Chroinin M, Greenstone I, Lasserson TJ. Addition of long-acting beta2-agonists to inhaled corticosteroids versus same dose inhaled corticosteroids for chronic asthma in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005535.pub2. Cd005535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sin DD, Man SF. Corticosteroids and adrenoceptor agonists: the compliments for combination therapy in chronic airways diseases. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;533:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]