Abstract

Purpose

The coronavirus lockdown in Italy ended, but the postlockdown phase may be even more challenging than the outbreak itself if the impact on mental health is considered. To date, little evidence is available about the effect of lockdown release in terms of adolescent health from the perspective of an emergency department (ED).

Methods

We reviewed data on ED arrivals of adolescents and young adults (aged 13–24 years) in the weeks immediately before and after the Italian lockdown release in 2020, and in the same periods in 2019, with a focus on cases of severe alcohol abuse, psychomotor agitation, and other mental issues.

Results

The relative frequency of severe alcohol intoxications increased from .88% during the last part of the lockdown to 11.3% after lockdown release. When comparing these data with the same period in 2019, a highly significant difference emerged, with severe alcohol intoxications accounting for 11.31% of ED visits versus 2.96%, respectively. The relative frequency of ED arrivals related to psychomotor agitation or other mental health issues was not significantly increased after lockdown release.

Conclusions

This report suggests that emergency services should be prepared for a possible peak of alcohol intoxication-related emergencies in adolescents and young adults. The connection between alcohol abuse and mental health should not be overlooked.

Keywords: Alcoholic intoxication, Adolescent, Emergency department, COVID

Implications and Contribution.

This report contributes to the field of adolescent and young adult health within the context of COVID-19 by raising the alarm on a possible peak of hospital admissions related to severe alcohol intoxications. It provides some of the first insights into the consequences of coronavirus lockdown from the perspective of an emergency department.

Italy has been the first country in Europe to experience a massive outbreak of COVID-19 infection. Trying to limit the spread of the infection, the Italian government established a national lockdown from March 9 to May 3. According to the government act, all public and private offices, factories, and commercial activities were closed, and people were allowed to leave their houses only for justified needs, such as purchase of food and essential goods, health conditions, and working reasons for those employed in public utility services. On May 4, 2020, the Italian national lockdown was withdrawn, and the emergency state for COVID-19 outbreak came to an end. Multiple evidence suggests that the coronavirus affected both physical health and psychological resilience, with a negative impact on population mental health [1,2]. The lockdown itself represented a stressor that triggered and relapsed the onset of mental illness: depression, anxiety, psychomotor agitation, suicide attempts, and substance abuse have been linked to this crisis [2]. Although the world is still being challenged by this new infectious disease, Italy begins to look beyond the crisis: so, what comes next? An alarm has recently been raised from the United Kingdom about the possible consequences of issues related to alcohol abuse after the end of the pandemic emergency phase [3], but very little is known about its impact on adolescent health [4].

From the observation point of the emergency departments (EDs) of a university children hospital and a university adult hospital in Trieste, an Italian city of 250,000 people, we experienced a peak of ED arrivals because of severe alcohol intoxications in adolescents and young adults immediately after the end of coronavirus lockdown. Both hospitals are the only facilities with an ED in the area, with a number of ED admissions per year of about 25,000 in the children's institute and 75,000 in the adult's one. An increase in the relative impact of severe alcohol intoxication on ED arrivals may represent an alarming sign for young people's mental health.

Methods

To verify the consistency of our observation on this increasing trend, we analyzed data on all ED visits of patients aged 13–24 occurred during the last 3 weeks of lockdown (April 10, 2020, to May 3, 2020), during the first 3 weeks after reopening (May 4, 2020, to May 27, 2020), and during the same periods in 2019 (April 10, 2020, to May 3, 2020, and May 4, 2019, to May 27, 2019) in both the considered hospitals. We extracted from hospital registries all ED discharge letters of patients belonging to the considered age group and manually reviewed their conclusions and discharge diagnosis. We obtained data on cases codified as severe alcohol abuse (defined as blood alcohol level >1.5 g/L associated to functional impairment), psychomotor agitation (defined as a state of loss of emotional and physical control, with altered behavior and risk of self-harm or injuries of others), and other mental health issues (including depression, psychosis, self-harm, anxiety, drug abuse, and eating disorders). In a pragmatic ED operational perspective, psychomotor agitation and other mental health issues are routine definitions and codified triage categories, determined by the triage nurse or the attending physician on clinical grounds. Data were extracted and reviewed independently by two researchers to minimize errors.

We compared the relative frequency of ED visits for each of the considered causes in the different periods using chi-square statistic.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained by the institutional review board (research protocol approval ID is RC14/20). Patients' data were treated anonymously, and all patients or their parents/guardians gave consent to anonymized data sharing and processing.

Results

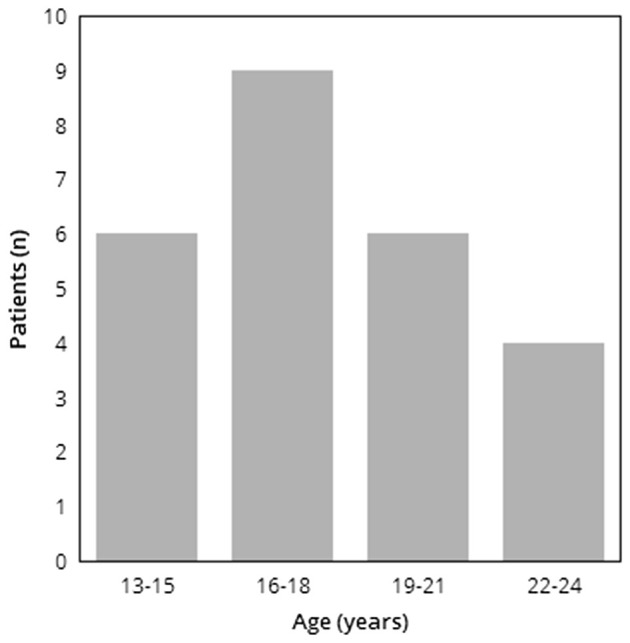

The total number of accesses to ED of patients in the considered age range increased from 117 in the weeks before the end of lockdown to 221 in the weeks after reopening (Table 1 ). The relative frequency of visits due to alcohol abuse in the considered age group rose from .88% during the last part of the lockdown period to 11.31% after lockdown release (Table 2 ). When comparing the weeks after reopening with the same period in 2019 (Table 3 ), hospital statistics showed that despite a lower number of accesses to ED, the absolute number of patients presenting with severe alcohol intoxication increased (25 vs. 15). In relative terms, a significant greater proportion of ED visits immediately after reopening were related to alcohol abuse, namely, 11.31% in the Year 2020 versus 2.96% in the Year 2019. Among those admitted to ED for severe alcoholic intoxication after the end of lockdown, 68% were males, and the median age was 17.0 years, with 16–18 years being the most frequent age range (Figure 1 ). The average blood alcohol level was 2.4 g/L (range 1.7–3.2), and 32% presented with a combined intake of alcohol and drugs, mainly cannabinoids. All patients arrived at the ED by ambulance transport and received intravenous fluid therapy and close monitoring. Remarkably, three patients in this cohort experienced severe complications as a consequence of the abuse: two of them were diagnosed with multiple fractures and severe head trauma, requiring computed tomography scans and neurosurgical observation. A third one required sedation for severe agitation with self-injuring. He was treated with two successive doses of intravenous midazolam with no benefit, followed by a dose of intravenous ketamine. After ketamine infusion, he vomited with lung inhalation requiring intubation and intensive care admission. More than half of the patients admitted for severe alcohol intoxication after the end of the lockdown had a past medical history of substance abuse or psychiatric disorder. The relative frequency of ED arrivals related to psychomotor agitation or other mental health issues was not significantly increased, neither compared with the weeks before reopening nor compared with the previous year (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 1.

Number of patients aged 13–24 years visited at ED in different time periods by arrival cause

| 2019 |

2020 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aptil 10 to May 3 | May 4 to May 27 | April 10 to May 3 Lockdown |

May 4 to May 27 Reopening |

|

| Total ED admissions, n | 305 | 506 | 117 | 221 |

| Alcohol abuse, n (%) | 9 (2.95) | 15 (2.96) | 1 (.88) | 25 (11.31) |

| Psychomotor agitation, n (%) | 4 (1.31) | 20 (3.95) | 4 (3.42) | 12 (5.43) |

| Other mental health issues, n (%) | 5 (1.64) | 8 (1.58) | 3 (2.56) | 3 (1.36) |

ED = emergency department.

Table 2.

Demographic data of patients visited at ED and comparison between relative frequency of arrival causes before and after reopening

| April 10, 2020, to May 3, 2020 Lockdown |

May 4, 2020, to May 27, 2020 Reopening |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total ED admissions, n | 117 | 221 | |

| Alcohol abuse, n (%) | 1 (.88) | 25 (11.31) | <.01 |

| Median age, years | 20.0 | 17.0 | |

| Males, % | 100.00 | 68.00 | |

| Psychomotor agitation, n (%) | 4 (3.42) | 12 (5.43) | .41 |

| Median age, years | 18.0 | 17.5 | |

| Males, % | 75.00 | 58.33 | |

| Other mental health issues, n (%) | 3 (1.71) | 3 (1.36) | .42 |

| Median age, years | 18.5 | 16.5 | |

| Males, % | 66.67 | 33.33 |

ED = emergency department.

Table 3.

Demographic data of patients visited at ED and comparison between relative frequency of arrival causes after reopening and in the same period in year 2019

| May 4, 2019, to May 27, 2019 Previous year |

May 4, 2020, to May 27, 2020 Reopening |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total ED admissions, n | 506 | 221 | |

| Alcohol abuse, n (%) | 15 (2.96) | 25 (11.31) | <.01 |

| Median age, years | 18.0 | 17.0 | |

| Males, % | 53.33 | 68.00 | |

| Psychomotor agitation, n (%) | 20 (3.95) | 12 (5.43) | .37 |

| Median age, years | 16.5 | 17.5 | |

| Males, % | 60.00 | 58.33 | |

| Other mental health issues, n (%) | 8 (1.58) | 3 (1.36) | .82 |

| Median age, years | 16.0 | 16.5 | |

| Males, % | 25.00 | 33.33 |

ED = emergency department.

Figure 1.

Age distribution of patients arrived to ED for severe alcoholic intoxication after reopening (May 4, 2020, to May 27, 2020).

Discussion

This study reports on the increase of ED visits due to severe alcohol abuse among adolescents and young adults after the end of COVID-19 lockdown in an Italian city. There are some limitations that need to be acknowledged: first, we had to rely on a retrospective data collection based on a systematic revision of hospital records, without a computerized data extraction system. This may have increased the risk of data extraction errors. Second, because of the limited size of the samples, random fluctuations in data cannot be excluded. Third, our data refer to a single city, so that their relevance is not universal.

However, we think that our data may contribute to raise a timely issue. The pandemic spread reduced outdoor time and social interaction and caught our mental health facilities unprepared to react, limiting the access to the necessary psychiatric support. For young people with fragile mental health, such closures meant a lack of access to the resources they usually have and need [5,6]. The lower number of ED visits registered in the first weeks after reopening, in comparison to 2019, was to be expected and is consistent with the COVID-19 related “hospital fear,” which prevent people from seeking medical care [7]. However, our data show that besides the relative frequency, also the absolute number of severe alcohol intoxications rose. Considering that the reference population did not change and that other emergency facilities are not available in the area, these numbers seem to reflect an actual change in the relative impact of severe alcohol intoxication on ED arrivals. Interestingly, the visits for psychomotor agitation or other psychiatric issues did not show the same trend. This may be related to the existing differences in the pathological processes and in their respective triggering mechanisms: alcohol abuse is strictly connected to social interaction within peer groups and may be triggered by an uncontrolled emotional response to the end of the lockdown. On the contrary, psychomotor agitation and other mental health issues may have found in the COVID-19 dynamics (i.e., social isolation and uncertainty about the future) a predisposing factor. Actually, their relative impact on ED arrivals did not decrease during lockdown; therefore, they were not subjected to a rebound effect after reopening. Nevertheless, the connection between alcohol abuse and mental health should not be overlooked. Even if the silver lining of the quarantine is overcoming coronavirus, the psychological and behavioral implications on mental health may endure, and they should be acknowledged as a likely cause of collateral setback. The lockdown–reopening transition demands rapid adjustment and appropriate reintegration strategies, requiring mental skills that not everyone is able to implement [8]. We believe that, despite needing to be confirmed on a larger scale, these data may deserve some attention.

Excesses belong to the typical pattern of behavior of adolescents and young adults, but to this extent, they may even result in life-threatening events. Based on this experience, we suggest that both pediatric and adult services should be prepared for a possible peak of emergencies related to alcohol abuse.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Shigemura J., Ursano R.J., Morganstein J.C. Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Japan: Mental health consequences and target populations. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;74:281–282. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park S.C., Park Y.C. Mental health care measures in response to the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Korea. Psychiatry Investig. 2020;17:85–86. doi: 10.30773/pi.2020.0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finlay I., Gilmore I. Covid-19 and alcohol—a dangerous cocktail. BMJ. 2020;369:m1987. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emans S.J., Ford C.A., Irwin C.E., Jr. Early COVID-19 impact on adolescent health and medicine programs in the United States: LEAH Program Leadership Reflections. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma V., Reinza Ortiz M., Sharma N. Risk and protective factors for adolescent and young adult mental health within the context of COVID-19: A perspective from Nepal. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67:135–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golberstein E., Wen H., Miller B.F. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-2019) and mental health for children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 Apr 14 doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lazzerini M., Barbi E., Apicella A. Delayed access or provision of care in Italy resulting from fear of COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020 May;4:e10–e11. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30108-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holmes E.A., O’Connoer R.C., Perry V.H. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID 2019 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 Jun;7:547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]