Abstract

The 2017 American College of Cardiology / American Heart Association blood pressure guideline recommends ambulatory blood pressure monitoring to detect masked hypertension. Data on the short-term reproducibility of masked hypertension are scarce. The Improving the Detection of Hypertension study enrolled 408 adults not taking antihypertensive medication from 2011–2013. Office blood pressure and 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring were performed on two occasions, a median of 29 days apart. After excluding participants with office hypertension (mean systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 80 mm Hg), the analytical sample included 254 participants. Using the Kappa statistic, we evaluated the reproducibility of masked awake hypertension (awake systolic/diastolic blood pressure ≥ 130/80 mm Hg) defined by the 2017 blood pressure guideline thresholds, as well as masked 24-hour (24-hour systolic/diastolic blood pressure ≥ 125/75 mm Hg), masked asleep (asleep systolic/diastolic blood pressure ≥ 110/65 mm Hg), and any masked hypertension (high awake, 24-hour, and/or asleep blood pressure). The mean (SD) age of participants was 38.0 (12.3) years and 65.7% were female. Based on the first and second ambulatory blood pressure recordings, 24.0% and 26.4% of participants, respectively, had masked awake hypertension. The Kappa statistic (95% CI) was 0.50 (0.38 to 0.62) for masked awake, 0.57 (0.46 to 0.69) for masked 24-hour, 0.57 (0.47 to 0.68) for masked asleep, and 0.58 (0.47 to 0.68) for any masked hypertension. Clinicians should consider the moderate short-term reproducibility of masked hypertension when interpreting the results from a single ambulatory blood pressure recording.

Keywords: Masked hypertension, reproducibility, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Some individuals not taking antihypertensive medication exhibit high out-of-office blood pressure (BP) without high office BP, a phenotype known as masked hypertension.1, 2 Masked hypertension is associated with an increased risk of target organ damage, cardiovascular disease, stroke, and mortality compared to sustained normotension (having neither high office nor high out-of-office BP).2–7 Ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) is recommended by the 2017 American College of Cardiology (ACC) / American Heart Association (AHA) BP guideline to screen for masked hypertension.8 However, there is limited information regarding the short-term reproducibility of masked hypertension defined using this guideline’s recommended thresholds for high office and out-of-office BP.

Prior studies, which used alternative definitions of high office BP (mean SBP/DBP ≥ 140/90 mm Hg) and high BP on ABPM (mean awake SBP/DBP ≥ 135/85 mm Hg and/or mean 24-hour SBP/DBP ≥ 130/80 mm Hg), recommended prior to the 2017 ACC/AHA BP guideline and outside of the US, demonstrated fair to modest short-term reproducibility (Kappa 0.30 to 0.47) of masked hypertension.9–12 In comparison, the 2017 ACC/AHA BP guideline recommends the use of lower thresholds to define both high office BP and high BP on ABPM. It defines masked hypertension as mean office SBP/DBP < 130/80 mm Hg averaged across more than one visit and awake mean SBP/DBP ≥ 130/80 mm Hg.

Currently, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) only reimburses the cost for a single ABPM claim per patient per year. Therefore, understanding the reliability of a single 24-hour ABPM for the diagnosis of masked hypertension is highly relevant.13 In the current study, we examined the short-term reproducibility of masked hypertension defined using the office BP and awake ABPM thresholds recommended in the 2017 ACC/AHA BP guideline. We also performed additional analyses: (1) to examine the reproducibility of a diagnosis of masked hypertension using mean 24-hour and mean asleep BP on ABPM, which are recommended in European hypertension guidelines14 but not the 2017 ACC/AHA BP guideline; and (2) to evaluate the reproducibility of masked hypertension using alternative definitions of high office BP and high BP on ABPM.

METHODS

The data, methods used in the analysis, and materials used to conduct the research will be made available to other researchers upon request to JES (jes2226@cumc.columbia.edu).

Study Population

The Improving the Detection of Hypertension (IDH) study was a community-based study designed to compare different strategies for diagnosing hypertension, and involved repeated assessments of office BP, ambulatory BP and home BP.15, 16 Office BP was measured using both the auscultatory method with a mercury sphygmomanometer and the oscillometric method using validated devices. The study enrolled 408 women and men, age 18 years and older, who were not taking antihypertensive medication and were free from known cardiovascular disease (CVD) in the New York City metropolitan area between March 2011 and October 2013. Participants were excluded if they had a screening office BP ≥ 160/105 mm Hg, evidence of secondary hypertension, or were taking medications that affect BP. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Columbia University and all participants provided written informed consent.15, 16

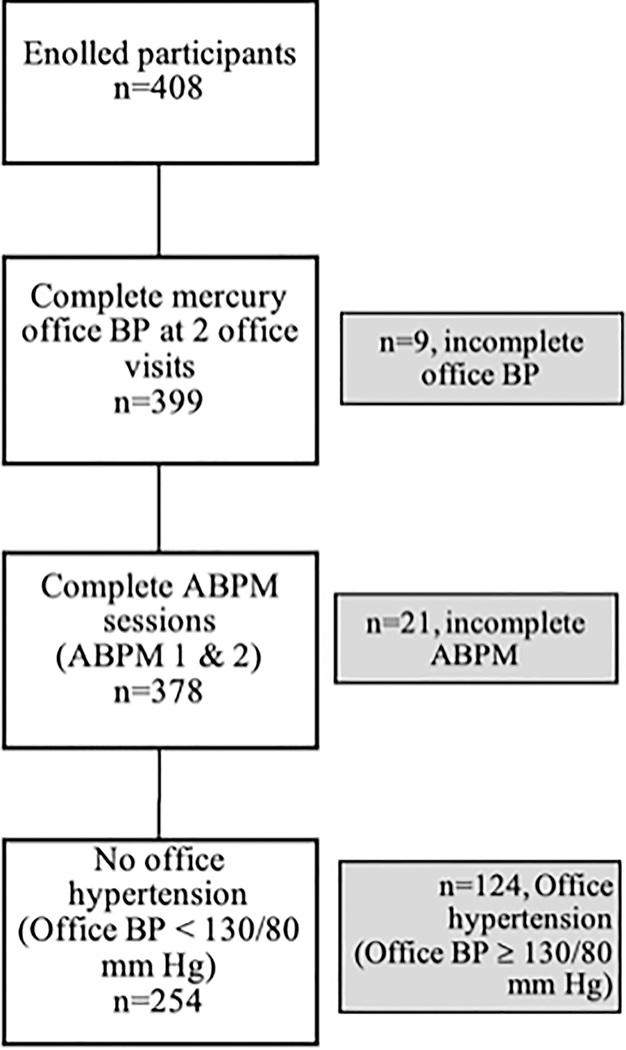

For the current investigation, we examined BP data from the two ABPM sessions (ABPM 1 and ABPM 2), and the two office visits that occurred just prior to each ABPM session. Participants were excluded from the current analysis if they had incomplete office BP data, defined as having fewer than two of the three mercury sphygmomanometer measurements at either office visit (N=9). An additional 21 participants were excluded due to incomplete ambulatory BP data at either session, defined by the International Database of Ambulatory Blood Pressure in Relation to Cardiovascular Outcome (IDACO) criteria, as fewer than 10 awake or 5 asleep readings, leaving 378 participants with complete office and ambulatory BP data.17 The analysis was further restricted to the 254 participants without office hypertension who had mean office SBP < 130 mm Hg and mean office DBP < 80 mm Hg using the readings averaged across the two office visits (Figure 1).8

Figure 1. Inclusion cascade for the analysis on the reproducibility of masked hypertension in the auscultatory office blood pressure sample.

Legend: ABPM = ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; BP = blood pressure.

Office BP was calculated as the mean of all office BP measurements. Complete office BP defined as ≥ 2 BP measurements at office visit 1 and office visit 2.

Complete ABPM defined by International Database of Ambulatory Blood Pressure in Relation to Cardiovascular Outcome [IDACO] criteria: ≥10 daytime and ≥5 nighttime readings, at both ABPM 1 and ABPM 2.

Study Procedures

Demographics (age, sex, race, and ethnicity), smoking status, and alcohol use were ascertained via a self-administered questionnaire and cardiovascular risk factors were obtained from a structured interview. Alcohol consumption was categorized as nondrinker (0 drinks per week), light/moderate drinker (1–7 drinks per week for females, 1–14 drinks per week for males) or heavy drinker (>7 drinks per week for females, >14 drinks per week for males). Height and weight were measured following a standardized protocol and these measurements were used to calculate body mass index (BMI) as weight in kilograms (kg) divided by height in meters squared (m2). Diabetes history was self-reported. Albuminuria was defined as urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio ≥ 30 mg/g. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation.18 Chronic kidney disease was defined as having reduced eGFR (eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2) or albuminuria.

During a study visit scheduled after the second ABPM, participants underwent a 2-dimensional echocardiogram with standard image acquisition. This included primary measures of left ventricular (LV) dimensions, volumes, and wall thickness, obtained in accordance with recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE).19 LV mass was calculated using the ASE formula and LV mass index was calculated as LV mass divided by body surface area, derived by the DuBois method.20 LV hypertrophy was defined as LV mass index >95 g/m2 for females and >115 g/m2 for males.19

Office BP Measurement

Following five minutes of seated rest, office BP was measured at each visit using an appropriately sized cuff on the non-dominant arm, with at least one minute between readings.21 All readings were performed by a trained research technician using both the auscultatory method with a mercury sphygmomanometer (Baum, Copiague, NY) and an oscillometric device (Omron HEM-790IT [HEM-7080-ITZ2] or HEM-791IT [HEM-7222-ITZ], Omron Healthcare, Kyoto, Japan)22 The device order was randomized across visits for each participant. Three readings were obtained using each method.

Ambulatory BP Measurement

ABPM was conducted using the Spacelabs 90207 device (Snoqualmie, WA) 23 and an appropriately sized cuff. SBP and DBP were measured every 30 minutes for 24 hours on the non-dominant arm. Participants were also fitted with a wrist actigraphy device (ActiWatch; Philips Respironics, Murrysville, PA) that was worn on the same arm as the ABPM. The awake and asleep periods were defined from the actigraphy data, supplemented by participants’ self-reported sleep/wake times.15, 16, 24 Awake and asleep SBP and DBP were calculated as the mean of all available readings during the respective periods, and 24-hour BP was calculated as the mean of all available readings.

Definition of Masked Hypertension Categories

High awake BP was defined as mean awake SBP ≥ 130 mm Hg and/or mean awake DBP ≥ 80 mm Hg, high 24-hour BP was defined as mean 24-hour SBP ≥ 125 mm Hg and/or mean 24-hour DBP ≥ 75 mm Hg, and high asleep BP was defined as mean asleep SBP ≥ 110 mm Hg and/or mean asleep DBP ≥ 65 mm Hg.8 As the current analysis was restricted to participants without a high mean office BP (mean office SBP < 130 mm Hg and DBP < 80 mm Hg), those with high awake, 24-hour, or asleep BP were categorized as having masked awake, masked 24-hour, or masked asleep hypertension, respectively. Any masked hypertension was defined as meeting criteria for masked awake, 24-hour, and/or asleep hypertension.

Statistical Analyses

Participants’ characteristics were summarized as mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. The mean (SD) SBP and DBP were calculated for office, awake, 24-hour, and asleep BP. The difference between the first and second ABPM readings (ABPM 2 minus ABPM 1) for each BP measure was calculated and we tested if it differed from zero using a paired t-test. Bland-Altman difference plots were created to examine within-person differences between ABPM 1 and 2 for awake, asleep and 24-hour SBP and DBP. We calculated the proportion of participants with each type of masked hypertension (awake, 24-hour, asleep, and any) on both ABPM 1 and 2, only ABPM 1, only ABPM 2, and neither ABPM 1 nor 2, and calculated the overall percent agreement and Kappa statistic and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs).25 The overall percentage agreement was calculated based on concordant classification of masked hypertension from ABPM 1 and 2, i.e. presence of masked hypertension on both ABPM 1 and 2 or absence of masked hypertension on both ABPM 1 and 2. As previously proposed, a Kappa statistic of 0.00–0.20 was considered to represent slight agreement, 0.21–0.40 represented fair agreement, 0.41–0.60 represented moderate agreement, 0.61–0.80 represented substantial agreement, and 0.81–1.00 represented nearly perfect agreement.26

Sensitivity Analyses

In the first sensitivity analyses, a separate analytic sample (N=261) was created using the office BP readings measured via the oscillometric method, rather than those measured using the auscultatory method with a mercury sphygmomanometer, to determine non-high office BP (Figure S1). Using that sample, we repeated all statistical procedures outlined above to evaluate the prevalence and reproducibility of masked hypertension. In a second sensitivity analysis, we evaluated the reproducibility of masked hypertension using alternative BP thresholds that were used in the US prior to the 2017 ACC/AHA BP guideline and are currently used outside of the US to define high BP.14, 27, 28 Included in this analytic sample were participants with mean office BP < 140/90 mm Hg measured using the auscultatory method (N=345). Masked awake hypertension was defined as mean awake SBP ≥ 135 mm Hg and/or mean awake DBP ≥ 85 mm Hg, masked 24-hour hypertension as mean 24-hour SBP ≥ 130 mm Hg and/or mean 24-hour DBP ≥ 80 mm Hg, masked asleep hypertension as mean asleep SBP ≥ 120 mm Hg and/or mean asleep DBP ≥ 70 mm Hg. We again repeated all statistical procedures outlined above in the primary methods to evaluate the prevalence and reproducibility of masked hypertension in this analytic sample.

STATA MP Version 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) was used for analyses. A p-value of < 0.05 was used as the threshold for statistical significance.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

The mean (minimum-maximum) age of participants was 38.0 (18.3–81.8) years and 65.7% were female, 24.8% were African American, and 59.4% were Hispanic (Table 1). Diabetes was reported by 0.4% of participants, 4.7% had chronic kidney disease, 8.7% were current smokers and 73.2% and 7.1% were moderate and heavy drinkers, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants in the auscultatory office blood pressure sample

| Characteristic | N=254 |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 38.0 (12.3) |

| Female sex, % | 65.7 |

| African-American race, % | 24.8 |

| Hispanic ethnicity, % | 59.4 |

| Current smoker, % | 8.7 |

| Alcohol Use* | |

| Nondrinker, % | 19.7 |

| Moderate Drinker, % | 73.2 |

| Heavy Drinker, % | 7.1 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.6 (4.7) |

| Diabetes, % | 0.4 |

| Chronic kidney disease, % | 4.7 |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy, % | 3.5 |

The numbers in the table are displayed as mean (standard deviation) or percentage.

Alcohol use defined as: nondrinker (no weekly alcohol consumption), moderate drinker (1–14 and 1–7 alcoholic beverages per week for men and women, respectively), or heavy drinker (more than 14 and more than 7 alcoholic beverages per week for men and women, respectively)

Blood Pressure in the Office and on Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring

The mean (SD) office SBP/DBP using the auscultatory method across two office visits was 109.4 (9.4) / 71.3 (5.9) mm Hg (Table 2). The median (25th – 75th percentiles) interval between ABPM 1 and 2 was 29 (22 – 36) days. For both ABPM recordings, there were median (25th – 75th percentiles) 31 (28 – 33) valid awake BP readings, and 13 (11 – 15) valid asleep BP readings. There was no evidence of differences between ABPM 1 and 2 for awake, 24-hour, or asleep SBP or DBP. Bland-Altman plots show the within-person differences between ABPM 1 and 2 for awake, asleep and 24-hour systolic and diastolic BP (Figure S2).

Table 2.

Blood pressure in the office and on ambulatory BP monitoring at ABPM 1 and ABPM 2 in the auscultatory office blood pressure sample, N=254

| Office BP, mm Hg | ABPM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awake, mm Hg | 24-Hour, mm Hg | Asleep, mm Hg | |||

| Systolic | 109.4 ± 9.4 | ABPM 1 | 119.9 ± 9.5 | 115.8 ± 9.2 | 105.5 ± 10.3 |

| ABPM 2 | 120.6 ± 9.9 | 116.3 ± 9.7 | 105.1 ± 10.4 | ||

| Mean Difference (95% CI)* | 0.6 (−0.2 to 1.5) | 0.5 (−0.3 to 1.2) | −0.5 (−1.4 to 0.5) | ||

| Diastolic | 71.3 ± 5.9 | ABPM 1 | 74.8 ± 6.1 | 70.8 ± 5.7 | 60.8 ± 6.6 |

| ABPM 2 | 75.0 ± 6.0 | 71.1 ± 5.9 | 60.6 ± 7.4 | ||

| Mean Difference (95% CI)* | 0.3 (−0.3 to 0.9) | 0.3 (−0.2 to 0.8) | −0.2 (−0.9 to 0.5) | ||

ABPM = ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; BP = blood pressure; CI = confidence interval.

ABPM 2 minus ABPM 1

BP data are displayed as means ± standard deviation.

Prevalence and Short-Term Reproducibility of Masked Hypertension Diagnosis

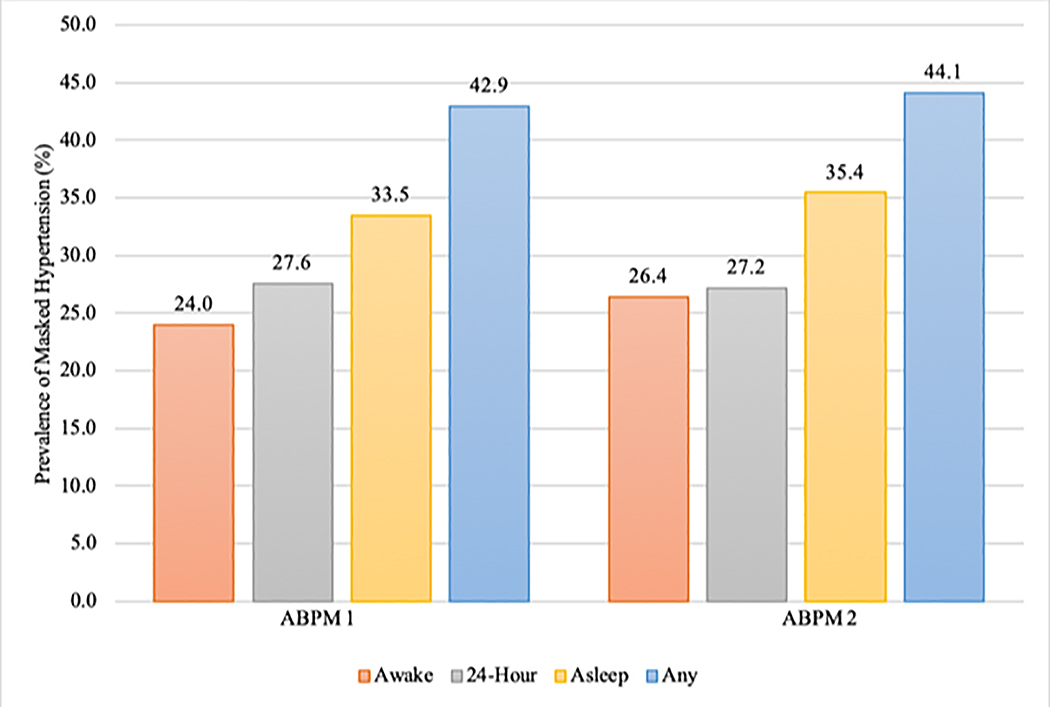

The prevalence of masked awake hypertension was 24.0% and 26.4% for ABPM 1 and ABPM 2, respectively (Figure 2) and 42.9% and 44.1% for any masked hypertension. The overall agreement (95% CI) between ABPM 1 and 2 was 81.1% (76.3 to 86.0%) for masked awake hypertension, 83.1% (78.4 to 87.7%) for masked 24-hour hypertension, 80.7% (75.8 to 85.6%) for masked asleep hypertension, and 79.1% (74.1 to 84.2%) for any masked hypertension (Table 3). The Kappa statistic (95% CI) for the short-term reproducibility was 0.50 (0.38 to 0.62) for masked awake hypertension. Additionally, the Kappa statistic was 0.57 (0.46 to 0.69), 0.57 (0.47 to 0.68), 0.58 (0.47 to 0.68) for 24-hour, asleep, and any masked hypertension, respectively.

Figure 2. Prevalence of each type of masked hypertension for ABPM 1 and ABPM 2 in the auscultatory office blood pressure sample.

Legend: ABPM = ambulatory blood pressure monitoring.

Masked awake hypertension is defined as mean awake SBP ≥ 130 mm Hg and/or mean awake DBP ≥ 80 mm Hg; masked 24-hour hypertension as mean 24-hour SBP ≥ 125 mm Hg and/or mean 24-hour DBP ≥ 75 mm Hg; masked asleep hypertension as mean asleep SBP ≥ 110 mm Hg and/or mean asleep DBP ≥ 65 mm Hg; and any masked hypertension on ABPM is defined as having masked awake hypertension, masked 24-hour hypertension, and/or masked asleep hypertension.

Table 3.

Prevalence and short-term reproducibility of the diagnosis of masked hypertension on ABPM among those without high office BP in the auscultatory office blood pressure sample

| A. | |||||

| Masked hypertension status | Masked awake hypertension on ABPM 2 N (%) | Overall percentage agreement (95% CI) | Kappa statistic (95% CI) | ||

| Present | Absent | ||||

| Masked awake hypertension on ABPM 1 N (%) | Present | 40 (15.7) | 21 (8.3) | 81.1 (76.3 to 86.0) | 0.50 (0.38 to 0.62) |

| Absent | 27 (10.6) | 166 (65.4) | |||

| B. | |||||

| Masked hypertension status | Masked 24-hour hypertension on ABPM 2 N (%) | Overall percentage agreement (95% CI) | Kappa statistic (95% CI) | ||

| Present | Absent | ||||

| Masked 24-hour hypertension on ABPM 1 N (%) | Present | 48 (18.9) | 22 (8.7) | 83.1 (78.4 to 87.7) | 0.57 (0.46 to 0.69) |

| Absent | 21 (8.3) | 163 (64.2) | |||

| C. | |||||

| Masked hypertension status | Masked asleep hypertension on ABPM 2 N (%) | Overall percentage agreement (95% CI) | Kappa statistic (95% CI) | ||

| Present | Absent | ||||

| Masked Asleep hypertension on ABPM 1 N (%) | Present | 63 (24.8) | 22 (8.7) | 80.7 (75.8 to 85.6) | 0.57 (0.47 to 0.68) |

| Absent | 27 (10.6) | 142 (55.9) | |||

| D. | |||||

| Masked hypertension status | Any masked hypertension on ABPM 2 N (%) | Overall percentage agreement (95% CI) | Kappa statistic (95% CI) | ||

| Present | Absent | ||||

| Any masked hypertension on ABPM 1 N (%) | Present | 84 (33.1) | 25 (9.8) | 79.1 (74.1 to 84.2) | 0.58 (0.47 to 0.68) |

| Absent | 28 (11.0) | 117 (46.1) | |||

ABPM = ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; BP = blood pressure; CI = confidence interval.

Panel A: Masked awake hypertension on ABPM. Panel B: Masked 24-hour hypertension on ABPM. Panel C: Masked asleep hypertension on ABPM. Panel D: Any masked hypertension on ABPM.

Masked awake hypertension is defined as mean awake SBP ≥ 130 mm Hg and/or mean awake DBP ≥ 80 mm Hg; masked 24-hour hypertension as mean 24-hour SBP ≥ 125 mm Hg and/or mean 24-hour DBP ≥ 75 mm Hg; masked asleep hypertension as mean asleep SBP ≥ 110 mm Hg and/or mean asleep DBP ≥ 65 mm Hg; and any masked hypertension on ABPM is defined as having masked awake hypertension, masked 24-hour hypertension, and/or masked asleep hypertension.

Sensitivity Analyses Using the Oscillometric Method

Demographics and mean office and ABPM values for the 261 participants included in this sensitivity analysis are presented in Tables S1 and S2. The prevalence of masked awake hypertension was 25.7% and 26.8% for ABPM 1 and 2, respectively (Figure S3). The overall agreement (95% CI) for masked awake hypertension between ABPM 1 and 2 was 82.0% (77.3 to 86.7%) with a Kappa statistic (95% CI) of 0.53 (0.42 to 0.65) (Table S3). The Kappa statistic (95% CI) was 0.59 (0.49 to 0.70), 0.59 (0.48 to 0.69), and 0.60 (0.51 to 0.70) for masked 24-hour hypertension, masked asleep hypertension and any masked hypertension, respectively.

Sensitivity Analysis Using Alternate BP Thresholds

When using alternative BP thresholds for high office BP and high BP on ABPM,14, 27, 28 the average (SD) office SBP/DBP across two visits using the auscultatory method was 113.2 (11.2) / 74.5 (7.6) mm Hg (Table S4). The percentage agreement (95% CI) was 87.5% (84.0 to 91.0%) and the Kappa statistic (95% CI) was 0.62 (0.51 to 0.72) for masked awake hypertension (Table S5). The Kappa statistic (95% CI) was 0.64 (0.54 to 0.74), 0.64 (0.55 to 0.74), and 0.65 (0.56 to 0.74) for masked 24-hour hypertension, masked asleep hypertension and any masked hypertension, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In this community-based sample, there is moderate short-term reproducibility for masked awake hypertension using the current ACC/AHA BP guideline’s recommended BP thresholds for high awake BP among adults without office hypertension. The reproducibility of masked hypertension is also moderate when using 24-hour BP, asleep BP, or BP during any of the three periods. The results are similar regardless of whether office BP was measured using the auscultatory method with a mercury sphygmomanometer or when using a validated oscillometric device.

The current analysis was performed in that subset of IDH study participants who did not have office hypertension. In contrast, prior studies that examined the reproducibility of masked hypertension included participants with high office BP, who by definition cannot have masked hypertension.9–12 The approach used in the current study is consistent with the 2017 ACC/AHA BP guideline, which recommends ABPM for the evaluation of masked hypertension only among those without office hypertension.8 We also examined the use of asleep BP and the combined use of BP status during all periods (awake, 24-hour, asleep) to categorize masked hypertension status and found similar levels of agreement results for all time periods. Although not incorporated into the 2017 ACC/AHA BP guideline, European guidelines recommend the integration of the awake, asleep, and 24-hour ABPM into the definition of out-of-office hypertension.14, 27, 29

Recognizing that diagnostic thresholds for high office BP and high BP on ABPM have changed in the US, we have also provided information on the reproducibility of masked hypertension using alternative, commonly used thresholds to define high BP.14, 27, 28 These higher thresholds for both office BP (office BP < 140/90 mm Hg) and ABPM (awake BP ≥ 135/85 mm Hg or alternatively 24-hour BP ≥ 130/80 mm Hg) were also used in prior studies examining the short-term reproducibility of masked awake or 24-hour hypertension.9–12 When using these higher BP thresholds to define masked hypertension in the IDH cohort, the point estimates for the Kappa statistic were slightly higher and in the “substantial” range for reproducibility compared to the Kappa statistics’ point estimates obtained using the 2017 ACC/AHA BP guideline thresholds, though the confidence intervals overlapped between the two analyses. The 2017 ACC/AHA BP guideline lowered the diagnostic thresholds defining high BP based on CVD outcomes data and not data demonstrating better reproducibility associated with using the lower BP thresholds.8 Further, while we note the small difference in reproducibility between the two diagnostic BP thresholds, it is doubtful that this difference would impact the association between masked hypertension and CVD outcomes.

Although many guidelines consider ABPM to be the reference standard, the results of the current study indicate that ABPM does not have perfect reproducibility. The variability in ABPM likely results from expected day-to-day variability in physical activity, stress, mood, and sleep among other factors.30 The 2017 ACC/AHA BP guideline recommends ABPM as the preferred out-of-office modality to diagnose masked hypertension,8 and CMS recently expanded coverage for ABPM to include the diagnosis of masked hypertension.31 As a result, clinicians’ use of ABPM to diagnose masked hypertension is expected to increase, making the reproducibility of ABPM increasingly clinically relevant. The 2017 ACC/AHA BP guideline does not recommend repeating an ABPM session to confirm a diagnosis of masked hypertension.8 Further, CMS will reimburse only one ABPM session annually.31 A single ABPM recording was also used in the seminal studies that found an association between masked hypertension and target organ damage,32, 33 and many other studies that found an association between masked hypertension and adverse cardiovascular outcomes.6, 34, 35 However, given the moderate reproducibility of masked hypertension in the current study based on BP thresholds recommended in the 2017 ACC/AHA BP guideline to define high BP, there may be occasional clinical scenarios in which repeating ABPM will be important to definitively confirm or exclude a diagnosis of masked hypertension. For example, a repeat ABPM session may be considered if the initial ABPM does not demonstrate masked hypertension in a patient who reports high home BP or one with evidence of target organ damage. In many settings it is difficult for patients and providers to access ABPM even once, and thus a repeat ABPM may be impractical to implement. In addition, further studies are needed to investigate if it would be cost-effective to repeat ABPM within a year for an individual.

There are several strengths of the current study that should be noted. First, the study population was racially and ethnically diverse and contained more than 60% women. The prevalence of masked hypertension is generally higher in the African American population compared to the non-Hispanic white population, underscoring the importance of studying a diverse sample when studying masked hypertension.36 Second, office BP and ABPM were measured following standardized procedures and we used both mercury sphygmomanometer and a validated oscillometric device.8, 14, 37 We also used actigraphy measures supplemented by diaries to determine the awake and asleep periods during the ABPM, instead of using fixed time periods or self-reported sleep times alone.38 There are also potential limitations to this study that should be taken into consideration when interpreting the data. The IDH study did not include individuals taking antihypertensive medication, so these results may not apply to masked uncontrolled hypertension. The study population was young and relatively healthy with a low prevalence of comorbidities such as diabetes and chronic kidney disease and thus our findings may not be generalizable to older populations or those with comorbid conditions, and compared to the US population, Hispanic subjects were overrepresented. Due to small sample sizes among the sub-groups, we were unable to perform analyses examining the reproducibility of masked hypertension by sex, race, or ethnicity. Lastly, the office BP in the current study population of community dwelling adults free from office hypertension was relatively low. Only 36 participants had BP in the range for which the ACC/AHA 2017 BP guideline recommends screening for masked hypertension, precluding an analysis in this sub-group.

PERSPECTIVE

In the current study, ABPM had moderate short-term reproducibility for the diagnosis of masked awake hypertension among participants without office hypertension based on mean office BP across two visits and using thresholds for high BP defined by the 2017 ACC/AHA BP guideline. Additionally, there was moderate short-term reproducibility of masked 24-hour hypertension, masked asleep hypertension, and any masked hypertension. Based on the findings from the current study, clinicians should consider the clinical context when interpreting the results of a single 24-hour ABPM recording to diagnose masked hypertension and may consider repeating ABPM in some individuals.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What is New?

This analysis assessed the short-term reproducibility of masked hypertension using the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association blood pressure guideline’s diagnostic criteria and thresholds for high office and ambulatory blood pressure.

We evaluated the short-term reproducibility of masked hypertension defined using awake, 24-hour and asleep periods on ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, as well as a combination of any of the three periods.

Both the auscultatory method using a mercury sphygmomanometer and a validated oscillometric device were used to measure office blood pressure in this study.

What is Relevant?

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is recommended to diagnose masked hypertension.

Based on guidelines and Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services reimbursement policy, only one ambulatory blood pressure monitoring session is reimbursable per year in the US. Thus, clinicians must often interpret the results of a single monitoring session, making the reproducibility of masked hypertension an important question.

Summary

We found moderate short-term reproducibility for the diagnosis of masked hypertension using awake blood pressure as recommended in the ACC/AHA blood pressure guideline, as well as when using 24-hour and asleep blood pressure individually, and in combination with awake blood pressure.

Clinicians should consider the clinical context when interpreting the results of a single ambulatory blood pressure monitoring session when diagnosing masked hypertension among individuals without high mean office BP across two office visits.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF FUNDING: This work was supported by P01-HL047540, K24-HL125704, R01 HL139716, and R01 HL137818 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Cohen is supported by NHLBI fellowship training grant T32-HL007343–41. Dr. Pugliese is supported by NHLBI fellowship training grant T32 HL007854. Dr. Bello is supported by the NHLBI (K23 HL136853) and the Katz Foundation.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pickering TG, James GD, Boddie C, Harshfield GA, Blank S and Laragh JH. How Common is White Coat Hypertension? JAMA. 1988;259:225–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pickering TG, Davidson K, Gerin W and Schwartz JE. Masked Hypertension. Hypertension. 2002;40:795–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anstey DE, Pugliese D, Abdalla M, Bello NA, Givens R and Shimbo D. An Update on Masked Hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2017;19:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimbo D, Abdalla M, Falzon L, Townsend RR and Muntner P. Studies comparing ambulatory blood pressure and home blood pressure on cardiovascular disease and mortality outcomes: a systematic review. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2016;10:224–234.e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stergiou GS, Asayama K, Thijs L, Kollias A, Niiranen TJ, Hozawa A, Boggia J, Johansson JK, Ohkubo T, Tsuji I, Jula AM, Imai Y and Staessen JA. Prognosis of White-Coat and Masked Hypertension. Hypertension. 2014;63:675–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pierdomenico SD and Cuccurullo F. Prognostic value of white-coat and masked hypertension diagnosed by ambulatory monitoring in initially untreated subjects: an updated meta analysis. Am J of Hypertens. 2011;24:52–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Booth JN 3rd, Diaz KM, Seals SR, Sims M, Ravenell J, Muntner P and Shimbo D. Masked Hypertension and Cardiovascular Disease Events in a Prospective Cohort of Blacks: The Jackson Heart Study. Hypertension. 2016;68:501–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, MacLaughlin EJ, Muntner P, Ovbiagele B, Smith SC, Spencer CC et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: : A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:e13–e115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de la Sierra A, Vinyoles E, Banegas JR, Parati G, de la Cruz JJ, Gorostidi M, Segura J and Ruilope LM. Short-Term and Long-Term Reproducibility of Hypertension Phenotypes Obtained by Office and Ambulatory Blood Pressure Measurements. J Clin Hypertens. 2016;18:927–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viera AJ, Hinderliter AL, Kshirsagar AV, Fine J and Dominik R. Reproducibility of masked hypertension in adults with untreated borderline office blood pressure: comparison of ambulatory and home monitoring. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:1190–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Viera AJ, Lin FC, Tuttle LA, Olsson E, Stankevitz K, Girdler SS, Klein JL and Hinderliter AL. Reproducibility of masked hypertension among adults 30 years or older. Blood Press Monit. 2014;19:208–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Husain A, Lin FC, Tuttle LA, Olsson E and Viera AJ. The Reproducibility of Racial Differences in Ambulatory Blood Pressure Phenotypes and Measurements. Am J Hypertens. 2017;30:961–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dixon DL, Salgado TM, Luther JM and Byrd JB. Medicare reimbursement policy for ambulatory blood pressure monitoring: A qualitative analysis of public comments to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. J Clin Hypertens. 2019;21:1803–1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, Clement DL, Coca A, de Simone G, Dominiczak A, Kahan T, Mahfoud F, Redon J, Ruilope L, Zanchetti A, Kerins M, Kjeldsen SE, Kreutz R, Laurent S, Lip GYH, McManus R, Narkiewicz K, Ruschitzka F, Schmieder RE, Shlyakhto E, Tsioufis C, Aboyans V and Desormais I. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3021–3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Booth JN 3rd, Muntner P, Diaz KM, Viera AJ, Bello NA, Schwartz JE and Shimbo D. Evaluation of Criteria to Detect Masked Hypertension. J Clin Hypertens. 2016;18:1086–1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdalla M, Goldsmith J, Muntner P, Diaz KM, Reynolds K, Schwartz JE and Shimbo D. Is Isolated Nocturnal Hypertension A Reproducible Phenotype? Am J Hypertens. 2016;29:33–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thijs L, Hansen TW, Kikuya M, Bjorklund-Bodegard K, Li Y, Dolan E, Tikhonoff V, Seidlerova J, Kuznetsova T, Stolarz K, Bianchi M, Richart T, Casiglia E, Malyutina S, Filipovsky J, Kawecka-Jaszcz K, Nikitin Y, Ohkubo T, Sandoya E, Wang J, Torp-Pedersen C, Lind L, Ibsen H, Imai Y, Staessen JA and O’Brien E. The International Database of Ambulatory Blood Pressure in relation to Cardiovascular Outcome (IDACO): protocol and research perspectives. Blood Press Monit. 2007;12:255–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T and Coresh J. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Goldstein SA, Kuznetsova T, Lancellotti P, Muraru D, Picard MH, Rietzschel ER, Rudski L, Spencer KT, Tsang W and Voigt JU. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:1–39.e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du Bois D and Du Bois EF. A formula to estimate the approximate surface area if height and weight be known. 1916. Nutrition. 1989;5:303–11; discussion 312–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pickering TG. Principles and techniques of blood pressure measurement. Cardiol Clin. 2002;20:207–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coleman A, Steel S, Freeman P, de Greeff A and Shennan A. Validation of the Omron M7 (HEM-780-E) oscillometric blood pressure monitoring device according to the British Hypertension Society protocol. Blood Press Monit. 2008;13:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Brien E, Mee F, Atkins N and O’Malley K. Accuracy of the SpaceLabs 90207 determined by the British Hypertension Society protocol. J Hypertens. 1991;9:573–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwartz JE, Burg MM, Shimbo D, Broderick JE, Stone AA, Ishikawa J, Sloan R, Yurgel T, Grossman S and Pickering TG. Clinic Blood Pressure Underestimates Ambulatory Blood Pressure in an Untreated Employer-Based US Population: Results From the Masked Hypertension Study. Circulation. 2016;134:1794–1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Viera AJ and Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Family Med. 2005;37:360–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landis JR and Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Brien E, Parati G, Stergiou G, Asmar R, Beilin L, Bilo G, Clement D, de la Sierra A, de Leeuw P, Dolan E, Fagard R, Graves J, Head GA, Imai Y, Kario K, Lurbe E, Mallion JM, Mancia G, Mengden T, Myers M, Ogedegbe G, Ohkubo T, Omboni S, Palatini P, Redon J, Ruilope LM, Shennan A, Staessen JA, vanMontfrans G, Verdecchia P, Waeber B, Wang J, Zanchetti A and Zhang Y. European Society of Hypertension position paper on ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Hypertens. 2013;31:1731–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, Lackland DT, LeFevre ML, MacKenzie TD, Ogedegbe O, Smith SC Jr, Svetkey LP, Taler SJ, Townsend RR, Wright JT Jr, Narva AS and Ortiz E. 2014 Evidence-Based Guideline for the Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Report From the Panel Members Appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8)2014 Guideline for Management of High Blood Pressure2014 Guideline for Management of High Blood Pressure. JAMA. 2014;311:507–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parati G, Stergiou G, O’Brien E, Asmar R, Beilin L, Bilo G, Clement D, de la Sierra A, de Leeuw P, Dolan E, Fagard R, Graves J, Head GA, Imai Y, Kario K, Lurbe E, Mallion JM, Mancia G, Mengden T, Myers M, Ogedegbe G, Ohkubo T, Omboni S, Palatini P, Redon J, Ruilope LM, Shennan A, Staessen JA, vanMontfrans G, Verdecchia P, Waeber B, Wang J, Zanchetti A and Zhang Y. European Society of Hypertension practice guidelines for ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Hypertens. 2014;32:1359–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zawadzki MJ, Small AK and Gerin W. Ambulatory blood pressure variability: a conceptual review. Blood Press Monit. 2017;22:53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jensen TS CJ, Ashby L, Hakim R, Hutter J, Li C, Caplan S, McKesson R. Decision Memo for Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring (ABPM) (CAG-00067R2). July 2, 2019.

- 32.Liu JE, Roman MJ, Pini R, Schwartz JE, Pickering TG and Devereux RB. Cardiac and Arterial Target Organ Damage in Adults with Elevated Ambulatory and Normal Office Blood Pressure. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:564–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kotsis V, Stabouli S, Toumanidis S, Papamichael C, Lekakis J, Germanidis G, Hatzitolios A, Rizos Z, Sion M and Zakopoulos N. Target Organ Damage in “White Coat Hypertension” and “Masked Hypertension”. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21:393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Booth JN 3rd, Diaz KM, Seals SR, Sims M, Ravenell J, Muntner P and Shimbo D. Masked Hypertension and Cardiovascular Disease Events in a Prospective Cohort of Blacks: The Jackson Heart Study. Hypertension. 2016;68:501–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bjorklund K, Lind L, Zethelius B, Andren B and Lithell H. Isolated ambulatory hypertension predicts cardiovascular morbidity in elderly men. Circulation. 2003;107:1297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Redmond N, Booth JN 3rd, Tanner RM, Diaz KM, Abdalla M, Sims M, Muntner P and Shimbo D. Prevalence of Masked Hypertension and Its Association With Subclinical Cardiovascular Disease in African Americans: Results From the Jackson Heart Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e002284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muntner P, Einhorn PT, Cushman WC, Whelton PK, Bello NA, Drawz PE, Green BB, Jones DW, Juraschek SP, Margolis KL, Miller ER 3rd, Navar AM, Ostchega Y, Rakotz MK, Rosner B, Schwartz JE, Shimbo D, Stergiou GS, Townsend RR, Williamson JD, Wright JT Jr. and Appel LJ. Blood Pressure Assessment in Adults in Clinical Practice and Clinic-Based Research: JACC Scientific Expert Panel. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:317–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Booth JN 3rd, Muntner P, Abdalla M, Diaz KM, Viera AJ, Reynolds K, Schwartz JE and Shimbo D. Differences in night-time and daytime ambulatory blood pressure when diurnal periods are defined by self-report, fixed-times, and actigraphy: Improving the Detection of Hypertension study. J Hypertens. 2016;34:235–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.