Abstract

Objectives

High levels of organisational citizenship behaviour can enable nurses to cooperate with coworkers effectively to provide a high quality of nursing care during the outbreak of COVID-19. However, the association between autonomy, optimism, work engagement and organisational citizenship behaviour remains largely unexplored. This study aimed to test if the effect of autonomy on organisational citizenship behaviour through the mediating effects of optimism and work engagement.

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study.

Setting

The study was conducted in the Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital in China.

Participants

In total, 242 nurses who came from multiple areas of China to work at the Wuhan Jinyintan hospital during the COVID-19 epidemic participated in this study.

Methods

A serial mediation model (model 6) of the PROCESS macro in SPSS was adopted to test the hypotheses, and a 95% CI for the indirect effects was constructed by using Bootstrapping.

Results

The autonomy–organisational citizenship behaviour relationship was mediated by optimism and work engagement, respectively. In addition, optimism and work engagement mediated this relationship serially.

Conclusion

The findings of this study may have implications for improving organisational citizenship behaviour. The effects of optimism and work engagement suggest a potential mechanism of action for the autonomy–organisational citizenship behaviour linkage. A multifaceted intervention targeting organisational citizenship behaviour through optimism and work engagement may help improve the quality of nursing care among nurses supporting patients with COVID-19.

Keywords: health policy, organisation of health services, human resource management, COVID-19, change management, health & safety

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to test a serial mediation model among autonomy, optimism, work engagement and organisational citizenship behaviour.

The findings of this study have provided a better understanding for policymakers and nursing management about improving nurses’ organisational citizenship behaviour during the outbreak of COVID-19.

The measures used in this study were internationally recognised and appropriately standardised for the Chinese population.

The results cannot confirm causal directionality.

Introduction

The COVID-19 rapidly spread across the globe causing a worldwide pandemic. In China, the Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital was the first designated hospital to treat the COVID-19 epidemic. Due to Wuhan’s shortage of health providers, the Chinese government mobilised qualified personnel from across China to aid local medical staff in the city to treat the health crisis.1 As front line of healthcare providers, nurses play an important role as they spend the longest time caring for and have the most frequent interactions with patients. With a large number of nurses from across China coming to work with local medical staff in the Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital, it is a necessity that they cooperate effectively with each other in order to deliver high-quality medical care to patients with COVID-19. Cooperative behaviour is important as it can increase the efficiency of an organisation. However, some challenges and difficulties, such as diverse backgrounds, different work standards and different level of original hospitals, may pose a threat to enacting cooperative behaviour for nurses.

Organisational citizenship behaviour is one type of cooperative behaviour, which increases a person’s tendency towards helping and sharing information, demonstrating integrity and championing the institution.2 Nurses with high levels of organisational citizenship behaviour can cooperate with other medical staff effectively to deliver more efficient care and increase organisational effectiveness.3 Therefore, it is necessary to focus on nurses’ organisational citizenship behaviour during the COVID-19 epidemic in the Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital.

Researchers have shown an increased interest in work engagement among nurses due to its relationship with organisational citizenship behaviour. For example, the study conducted by Sulea et al4 showed that nurses with a high level of work engagement are more likely to have organisational citizenship behaviours. A study in Thailand also showed that there were positive relationships between work engagement and organisational citizenship behaviour.5 Additionally, researchers and practitioners are increasingly recognising that a clear understanding of antecedents for work engagement is in needed to inform intervention efforts to maximise organisational citizenship behaviours. One of the antecedents to work engagement is autonomy. Mauno et al6 in their longitudinal study demonstrated that autonomy can lead to work engagement. Moreover, Bargagliotti7 found that autonomy can positively impact work engagement among professional nurses. Studies, such as the one by Nordin et al8 found that optimism positively related to work engagement. The positive relationship between optimism and work engagement was also shown in a study conducted in Korea.9

Although previous studies have made valuable contributions to the topic about autonomy, optimism, work engagement and organisational citizenship behaviour, the mechanism (eg, how autonomy relates to organisational citizenship behaviour) underlying the association between optimism and work engagement remains largely unexplored. The contributions of the present study are twofold. First, it is the first to examine the association between autonomy, optimism, work engagement and organisational citizenship behaviour, thus generating new insights into the mechanisms underlying the effect of autonomy on organisational citizenship behaviour. Second, by using a sample of nurses, this study can help inform effective interventions to improve organisational citizenship behaviour among nurses caring for patients with COVID-19.

Theory and hypotheses

The Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model can be used to present an understanding of organisational citizenship behaviour within an occupational health psychiatry context. Job demands, such as workload or time pressure, can initiate a health impairment process, where emotional exhaustion is predicted to decrease job performance. In contrast, job resources, such as autonomy or performance feedback, can initiate a motivational process, where work engagement can be predicted, resulting in positive employee behaviour and job performance, including organisational citizenship behaviour and creativity.10 11

Autonomy is one type of job resource, and the extent to which the job provides discretion, freedom and independence can be reflected by autonomy.12 Autonomy can help individuals maintain positive learning through an intimate knowledge of their work, and during this process, employees become engaged.13 Work engagement refers to ‘a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterised by vigour, dedication and absorption’.14 When engaged individuals feel a high level of significance of their job, they are more likely to take pride in being assigned challenging tasks performing better in the workplace.15

In line with the JD-R model, the relationship between autonomy and employee behaviour can be mediated by work engagement. Surveys such as that conducted by Kwon and Kim16 have shown that work engagement plays a mediating role in the relationship between autonomy and employee behaviour. Keyko et al 17 found that autonomy can predict work engagement, leading to positive outcomes among professional nurses. Although extensive research has been carried out on work engagement, no single study exists which tests the mediating effect of work engagement in the relationship between autonomy and organisational citizenship behaviour. Thus, this study proposes:

Hypothesis 1

Work engagement will mediate the association between autonomy and organisational citizenship behaviour.

As the aspects of the work environment were only considered in the early and revised versions of the JD-R model, recently personal resources are suggested to be integrated into the JD-R model, due to the fact that human behaviour can be explained by an interaction between personal and environmental factors based on psychological approaches.18Personal resources are defined as ‘the psychological characteristics or aspects of the self that are generally associated with resiliency and that refer to the ability to control and impact one’s environment successfully’.18 This kind of resources has a similar function as job resources to improve personal growth and development.

Schaufeli19 suggested that though personal resources can be integrated and play an important role in the JD-R model, it is unclear where exactly they act. Schaufeli and Taris18 stated that there were five places when considering personal resources in the JD-R model and encouraged future research to collect more evidence to identify where and how personal resources act. One possible place for personal resources is that the relationship between job resources and work engagement can be mediated by personal resources.18 Optimism is an example of a personal resource. Seligman20 suggest that optimistic individuals consider that personal, permanent and pervasive factors result in positive events, and negative outcomes can be interpreted in terms of temporary, external and situation-specific factors. Optimistic people often view an event positively and internalise the good aspects of their lives in the past, present and future, thereby increasing their sense of self-esteem and morale.21 Studies have shown that optimism plays a mediating role in the positive relationship between job resources and work engagement, which is suggested by cross-sectional studies.22 23 Additionally, in a longitudinal study, Llorens et al found the association between job resources and work engagement can be mediated by personal resources (eg, efficacy).24 However, the mediating effect of optimism on the relationship between autonomy, work engagement and organisational citizenship has not been investigated.

In line with the JD-R model and the suggested place for optimism, optimism can be regarded as a mediator in the JD-R model. Thus, this study proposes:

Hypothesis 2

The relationship between autonomy and organisational citizenship behaviour will be serially mediated by optimism and work engagement.

Methods

Study units and participants

A convenience sample was used with nurses caring for patients with COVID-19 from the Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital, in March 2020. This study was conducted online via Wenjuanxing, which is the Chinese professional survey website (https://www.wjx.cn/). A two-dimensional code was sent to all potential participants, who can scan two-dimensional codes having access to the questionnaires through WeChat.

After obtaining agreement from head nurses, the research team sent the two-dimensional code of the electronic questionnaire to head nurses through WeChat. The head nurses then assisted with recruitment by sending the two-dimensional code to their nurses through WeChat. The first page of electronic questionnaire provided information about this study and information to allow participants to provide informed consent. Participation was voluntary and participants decided on an individual basis whether to take part in this study. The first page of electronic questionnaire also told participants that all data would be protected, and the survey was anonymous. A total of 305 nurses were invited and 242 nurses agreed to participate and completed the electronic questionnaire.

Measures

Autonomy

The autonomy subscale of the Job Diagnostic Survey was used to measure autonomy.25 It comprises three items, and the Chinese version of this scale is widely used.12 One example of an item on the questionnaire is: ‘My job gives me the chance to use my personal initiative and judgement in carrying out the work’.25 A seven-point scale ranging from ‘very little’ to ‘very much’ was rated by participants.

Optimism

Optimism was assessed with a subscale of the Life Orientation Test.26 The subscale comprised of four items, and the Chinese version of this scale was used in this study.27 One sample item in the short scale was ‘In uncertain times, I usually expect the best’. A five-point scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’ was rated by participants.

Work engagement

Work engagement was measured with the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale-9.28 There are three dimensions in this scale: three items for vigour, three items for dedication and three items for absorption. This scale has been widely used in China.29 The items are ‘to my job, I feel strong and vigorous’ and ‘in the morning, I feel like going to work’. A seven-point scale ranging from ‘never’ to ‘always’ was rated by participants.

Organisational citizenship behaviour

Organisational citizenship behaviour was measured with organisational citizenship behaviour scale.30 There are two dimensions and 10 items in this scale: 7 items for helping and 3 items for civic virtue. Examples of the items are ‘attend and actively participate in team meetings’ and ‘willingly share expertise with other members of the unit’. A five-point scale ranging from ‘completely not true’ to ‘completely true’ was rated by participants.

Statistical analysis

This study used IBM SPSS Statistics (V.24, IBM Corporation, New York, USA) to calculate descriptive information and correlation matrix. A serial mediation model (model 6) of the PROCESS macro in SPSSwas adopted to test the hypotheses.31 Bootstrapping is used in the mediation analysis because it is a non-parametric resampling technique involving random and repeated subsampling of data, and it does not need to satisfy the assumption of normally distributed data.31 A 95% CI for the indirect effects is constructed by using Bootstrapping. If the 95% CI does not contain zero, it is considered to be significant for the indirect effects. In this study, the mediating results were based on 5000 bootstrap samples.

A total effect, a direct effect and a total indirect effect can be provided in a serial mediation model. For a serial mediation model with two mediators (eg, optimism and work engagement), there are three specific indirect effects, and the specific indirect effects can be compared. Control variables should be included in studies when there are theoretically based justifications rather than previous empirical relationships.32 Therefore, control variables were not included in this study.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Table 1 presents means, SD, the Cronbach’s α, average variance extracted (AVE) and correlations of study variables. AVE for autonomy, optimism, work engagement and organisational citizenship behaviour was 0.71, 0.67, 0.50 and 0.63, respectively, which indicated that convergent validity was acceptable. The square of root of AVE values exceeded the construct correlation values suggesting that discriminant validity is satisfactory.

Table 1.

Correlation coefficient, mean, SD, and AVE (N=242)

| Variables | M | SD | The Cronbach’s α | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1. Autonomy | 5.56 | 1.27 | 0.89 | 0.71 | 0.84 | |||

| 2. Optimism | 4.17 | 0.70 | 0.87 | 0.67 | 0.36** | 0.82 | ||

| 3. WE | 4.83 | 1.01 | 0.92 | 0.50 | 0.49** | 0.54** | 0.71 | |

| 4. OCB | 5.01 | 0.78 | 0.95 | 0.63 | 0.35** | 0.47** | 0.60** | 0.79 |

**Significant at the 0.01 level; the square root of AVE values are bolded.

AVE, average variance extracted; OCB, organisational citizenship behaviour; WE, work engagement.

Mediation analyses

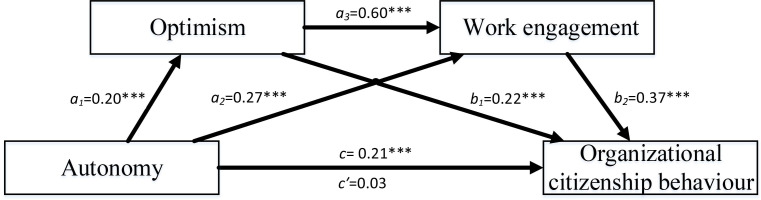

Model 6 of the PROCESS macro was adopted to test if the association between autonomy and organisational citizenship behaviour can be mediated serially by optimism and work engagement. The results are presented in figure 1 and table 2. The total indirect effect of autonomy on organisational citizenship behaviour was found to be significant (ab=0.19, SE=0.03, CI=0.13 to 0.26). The indirect effect of autonomy on organisational citizenship behaviour via optimism was significant (a1b1=0.04, SE=0.02, CI=0.01 to 0.09). The indirect effect of autonomy on organisational citizenship behaviour via work engagement was also significant (a2b2=0.10, SE=0.02, CI=0.06 to 0.15). The indirect effect of autonomy on organisational citizenship behaviour was also found to be significant through both optimism and work engagement (a1a3b2=0.04, SE=0.01, CI=0.02 to 0.07).

Figure 1.

Three-path mediation model. a1=direct effect of autonomy on optimism; a2=direct effect of autonomy on work engagement; a3=direct effect of optimism on work engagement; b1=direct effect of optimism on organisational citizenship behaviour; b2=direct effect of work engagement on organisational citizenship behaviour; c=total effect of autonomy on organisational citizenship behaviour, without accounting for optimism and work engagement; c′=direct effect of autonomy on organisational citizenship behaviour when accounting for optimism and work engagement. ***p<0.001.

Table 2.

Serial mediation analyses (N=242)

| Effect | b | SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

| ab | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.26 |

| a1 b1 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.09 |

| a2 b2 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.15 |

| a1 a3 b2 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| Contrasts | ||||

| a1 b1 minus a2 b2 | −0.06 | 0.03 | −0.13 | 0.01 |

| a1 b1 minus a1 a3 b2 | 0 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.04 |

| a2 b2 minus a1 a3 b2 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.11 |

Bootstrap sample size=5000. a and b represent unstandardised regression coefficients: a1=direct effect of autonomy on optimism; a2=direct effect of autonomy on work engagement; a3=direct effect of optimism on work engagement; b1=direct effect of optimism on organisational citizenship behaviour; b2=direct effect of work engagement on organisational citizenship behaviour; ab=total indirect effect; a1b1=specific indirect effect through optimism; a2 b2=specific indirect effect through work engagement; a1a3b1=specific indirect effect through optimism and work engagement

LLCI, lower limit of CI; ULCI, upper limit of CI.

All specific indirect effects were contrasted to determine whether one indirect effect is different than another (table 2). Only one pair of contrasting findings was found to be statistically significant (effect=0.06, SE=0.02, CI=0.01 to 0.11). The results showed that the indirect effect was larger through work engagement only than the path through both optimism and work engagement.

Discussion

The present study contributes to integrate optimism in the JD-R model as a mediator. Through the sample of nurses in the study, it was found that autonomy was associated with organisational citizenship behaviour through the following mechanisms: (1) indirectly through work engagement, (2) indirectly through both optimism and work engagement and (3) indirectly through optimism. This means that three specific indirect effects were found to be significant.

These findings suggest that a high level of autonomy was associated with a higher level of work engagement and thus was associated with greater organisational citizenship behaviour. This is consistent with an earlier study published from Korea, which showed that the relationship between job resources and performance was mediated work engagement.33 Similarly, in a study among nurses, Maurits et al 34 found that work engagement served as a mediator in the relationship between autonomy and intention to leave the healthcare sector. In a motivational process described by JD-R model, the indirect effect of job resources on employee behaviour can be mediated by work engagement.18 When independence and freedom of a job were given to nurses, they will work in a positive affective-motivational state, which can help generate attitudes and behaviours that lead to achieve goals. In turn, nurses are more likely to have beneficial voluntarily behaviours at work, such as organisational citizenship behaviour.

Despite the mediating role of optimism having been studied in the past, understanding of its connection to work engagement and employee behaviour is still unclear. Additionally, previous research shows that the relationship between job resources and motivation can be mediated by optimism.35 Xanthopoulou et al22 found that the relationship between day-level coaching and work engagement was mediated by optimism. However, this study suggested that an indirect effect of autonomy on organisational citizenship behaviour among nurses occurs via both optimism and work engagement. This serial mediation model has been demonstrated for the first time between these variables. Hobfoll36 proposes that resources intend to accumulate, which means that if employees work in an environment with rich resource, they are more likely to become optimistic and confident about career development.36 These personal resources can be positively related to work engagement. Work engagement can not only enable employees to be goal-oriented and focus on their work tasks but also provide the energy and enthusiasm to perform well. In other words, the mediating effect of personal resources suggests that existing resources can accumulate further resources, which are beneficial to job performance and employee behaviour.

Interestingly, the findings also suggest that the relationship between autonomy and organisational citizenship behaviour is mediated by optimism, which is not proposed in JD-R model. However, this result was consistent with the previous studies. For example, Le et al37 suggested that the relationship between job resources and employee behaviour was mediated by optimism. Similarly, optimism has also been found to has a mediating effect on the relationship between job resources (eg, salesperson knowledge) and salesperson performance.38 The reason may be that autonomy as a job resource gives nurses authority to choose task distribution, work pace, work skills and collaborators.39 Therefore, nurses can use a resource-rich working environment as an instrument to activate optimism, allowing them to have the ability to control their working environment and become confident, thus contributing to excellent job performance.36

In this study, three mediation models were significant. However, in comparing specific indirect effects of mediators, the findings indicated that the indirect effect was larger through work engagement only, compared with the path through both optimism and work engagement. Meanwhile, effect sizes for optimism as mediator were small in the single mediator path and serial multiple mediation, which limits practical significance of data. Therefore, the mediated capabilities of optimism should not be overestimated. Additionally, the other possible places for personal resources should be taken into account. For example, Schaufeli suggested that the relation between job characteristics and well-being (eg, work engagement) can be moderated by personal resources.19

Implications

Since optimism and work engagement are significant mediators in the autonomy–organisational citizenship behaviour linkage, a wide range of interventions should be adopted to improve optimism and work engagement among nurses fighting COVID-19. First, it is necessary for nursing management to boost nurses’ awareness of the underlying optimism by highlighting the concept of goals, as it allows nurses who were frustrated in the past, to design and implement strategies to achieve their goals.40 For instance, Zhang et al41 found that individuals can be taught about setting goals and developing measures to achieve them when facing adversity, thus leading to a forward-thinking, positive person. The findings of this present study also suggest that it is important for nursing management to focusing on improving work engagement. They should make an effort to provide an interesting and challenging work environment with sufficient job resources fitting nurses’ role expectations. Moreover, supportive management also plays a vital role, as it provides a positive climate containing more job resources and endurable job demands for nurses, resulting in a higher level of work engagement.14 For example, a study published from Japan has shown that psychological demands and decision latitude can increase work engagement.42

Limitations

When these findings were interpreted, some limitations should be considered. First, the results cannot be interpreted with causal directionality as the study had a cross-sectional design. Longitudinal or experimental designs are encouraged to confirm causal directionality. Second, common method variance may be a potential issue due to self-report questionnaires when interpreting the results. However, Harmon’s single-factor test was performed, and the results revealed that the explained variance of the first factor was below 50%. Additionally, four factors had an eigenvalue greater than 1.0. Therefore, common-method bias may not be a major issue in our study. Third, other types of personal resources, like self-efficacy, may also mediate the relationship between autonomy and organisational citizenship behaviour, so future studies are encouraged to adopt the different types of personal resources in this association. Finally, the purposes of the study were tested among nurses came across China working in Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital fighting COVID-19 epidemic, so the results may not be generalisable to other samples. However, as the COVID-19 epidemic has spread worldwide, nurses in other countries may also work temporarily with new colleagues to deliver treatment to patients with COVID-19. The findings of this study have provided a better understanding for policymakers and nursing management about improving nurses’ organisational citizenship behaviour.

Conclusion

Our framework aligns with the call19 to clarify the role of personal resources in the JD-R model. In a sample of nurses who came from across China to work in Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital during the COVID-19 epidemic, it was found that the relationship between autonomy and organisational citizenship behaviour is influenced by the sequential effects of optimism and work engagement. A high level of organisational citizenship behaviour can enable nurses to cooperate with other medical staff effectively to provide high quality of nursing care in this globe health emergency. Although future studies should focus on substantiating and improving the findings when considering the association between these important variables, nursing management and hospital administration should consider a multifaceted approach to enhance optimism and work engagement among nurses fighting COVID-19.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The first author wants to thank Mr Liangyuan Li, who provided her with tremendous assistance.

Footnotes

Contributors: HZ, YZ and ZHY designed the study. HZ, SHL, DDC, PZ and YZ analysed the data, and drafted the manuscript and interpreted the data. HZ, LWT, JS, ZHY, LY and PZ revised the manuscript. YZ and LY participated in the data collection. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. YZ—cofirst author. Hui Zhang, Yi Zhao are contributed equally to this study and share equal first authorship.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained from ethics committee of the third People’s Hospital of Hubei Province. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical principles set forth in Helsinki declaration. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.The National aided Hubei Anti-epidemic medical team departs. Available: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/s3578/202001/2d96f6f4f0e64e6f8613abfeeea3ca40.shtml

- 2.Organ DW, Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB. Organizational citizenship behavior: its nature, antecedents, and consequences. Sage Publications, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kazemipour F, Mohamad Amin S, Pourseidi B. Relationship between workplace spirituality and organizational citizenship behavior among nurses through mediation of affective organizational commitment. J Nurs Scholarsh 2012;44:302–10. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2012.01456.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sulea C, Virga D, Maricutoiu LP, et al. Work engagement as mediator between job characteristics and positive and negative extra‐role behaviors. Career Dev Int 2012;17:188–207. 10.1108/13620431211241054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rurkkhum S, Bartlett KR. The relationship between employee engagement and organizational citizenship behaviour in Thailand. Human Resource Dev Int 2012;15:157–74. 10.1080/13678868.2012.664693 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mauno S, Kinnunen U, Ruokolainen M. Job demands and resources as antecedents of work engagement: a longitudinal study. J Vocat Behav 2007;70:149–71. 10.1016/j.jvb.2006.09.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bargagliotti LA. Work engagement in nursing: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 2012;68:1414–28. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05859.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nordin NA, A Rashid YK, Panatik SA, et al. Relationship between psychological capital and work engagement. J Res Psychol 2019;1:6–12. 10.31580/jrp.v1i4.1115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joo BK, Lim DH, Kim S. Enhancing work engagement the roles of psychological capital, authentic leadership, and work empowerment. Leadership Org Dev J 2016;37:1117–34. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bakker AB, Demerouti E. The job demands‐resources model: state of the art. J Managerial Psychol 2007;22:309–28. 10.1108/02683940710733115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, et al. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J Appl Psychol 2001;86:499–512. 10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu C, Spector PE, Shi L. Cross-national job stress: a quantitative and qualitative study. J Organ Behav 2007;28:209–39. 10.1002/job.435 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bakker AB, Demerouti E. Multiple levels in job demands-resources theory: Implications for employee well-being and performance In: Handbook of well-being, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bakker AB. Strategic and proactive approaches to work engagement. Organ Dyn 2017;46:67–75. 10.1016/j.orgdyn.2017.04.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bakker AB, Demerouti E. Job demands-resources theory: taking stock and looking forward. J Occup Health Psychol 2017;22:273–85. 10.1037/ocp0000056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwon K, Kim T. An integrative literature review of employee engagement and innovative behavior: revisiting the JD-R model. Human Res Manage Rev 2020;30:100704 10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.100704 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keyko K, Cummings GG, Yonge O, et al. Work engagement in professional nursing practice: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 2016;61:142–64. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schaufeli WB, Taris TW. A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health : Bridging occupational, organizational and public health. Springer, 2014: 43–68. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schaufeli WB. Applying the job Demands-Resources model. Organ Dyn 2017;46:120–32. 10.1016/j.orgdyn.2017.04.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seligman ME. Learned optimism: how to change your mind and your life. Vintage, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luthans F, Human YCM. Human, social and now positive psychological capital management: investing in people for competitive advantage. Organ Dyn 2004;33:143–60. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xanthopoulou D, Bakker AB, Demerouti E, et al. The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. Int J Stress Manag 2007;14:121–41. 10.1037/1072-5245.14.2.121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corso-de-Zúñiga S, Moreno-Jiménez B, Garrosa E, et al. Personal resources and personal vulnerability factors at work: an application of the job Demands-Resources model among teachers at private schools in Peru. Curr Psychol 2020;39:325–36. 10.1007/s12144-017-9766-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Llorens S, Schaufeli W, Bakker A, et al. Does a positive gain spiral of resources, efficacy beliefs and engagement exist? Comput Human Behav 2007;23:825–41. 10.1016/j.chb.2004.11.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richard HJ, Oldham G. Motivation through the design of work: test of a theory. Organ Behav Human Perform 1976;16:250–79. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the life orientation test. J Pers Soc Psychol 1995;67:1063–78. 10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wen J, Xue F. Dispositional optimism, explanatory style and subjective well-being: a correlation research in college students. Psychol Res 2011;5. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB, Salanova M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire - A cross-national study. Educ Psychol Measure 2006;66:701–16. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong X, Lu H, Wang L, et al. The effects of job characteristics, organizational justice and work engagement on nursing care quality in China: a mediated effects analysis. J Nurs Manag 2020;28:559–66. 10.1111/jonm.12957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bachrach DG, Wang H, Bendoly E, et al. Importance of organizational citizenship behaviour for overall performance evaluation: comparing the role of task interdependence in China and the USA. Manag Organ Rev 2007;3:255–76. 10.1111/j.1740-8784.2007.00071.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. J Educ Measure 2013;51:335–7. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bernerth JB, Aguinis H. A critical review and best-practice recommendations for control variable usage. Pers Psychol 2016;69:229–83. 10.1111/peps.12103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim W. Examining mediation effects of work engagement among job resources, job performance, and turnover intention. Perf Improvement Qrtly 2017;29:407–25. 10.1002/piq.21235 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maurits EEM, de Veer AJE, van der Hoek LS, et al. Autonomous home-care nursing staff are more engaged in their work and less likely to consider leaving the healthcare sector: a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud 2015;52:1816–23. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang J, Wang Y, You X. The job Demands-Resources model and job burnout: the mediating role of personal resources. Curr Psychol 2016;35:562–9. 10.1007/s12144-015-9321-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources. A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol 1989;44:513–24. 10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Le BP, Lei H, Phouvong S, et al. Self-efficacy and optimism mediate the relationship between transformational leadership and knowledge sharing. Soc Behav Personal Int J 2018;46:1833–46. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sangtani V. Revisiting Salesperson knowledge: the role of optimism. Thriving in a new world economy. Springer, 2016: 210–3. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karasek RA. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q 1979;24:285–308. 10.2307/2392498 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grover SL, Teo STT, Pick D, et al. Psychological capital as a personal resource in the JD-R model. Personnel Rev 2018;47:968–84. 10.1108/PR-08-2016-0213 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang X, Li Y-L, Ma S, et al. A structured reading Materials-Based intervention program to develop the psychological capital of Chinese employees. Soc Behav Personal Int J 2014;42:503–15. 10.2224/sbp.2014.42.3.503 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Inoue A, Kawakami N, Tsuno K, et al. Job demands, job resources, and work engagement of Japanese employees: a prospective cohort study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2013;86:441–9. 10.1007/s00420-012-0777-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.