Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to explore the association between maternal satisfaction and other indicators of quality of care (QoC) at childbirth, as defined by WHO standards.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Referral hospital in Northeast Italy.

Participants

1244 consecutive mothers giving birth in the hospital participated in a survey.

Data collection and analysis

Univariate analyses were performed to evaluate the association between maternal satisfaction and 61 variables, including measures of ‘provision of care’, ‘experience of care’, ‘availability of resources’ and other maternal characteristics. Exploratory factor analysis was performed to create groups of correlated variables, which were used in multivariate analysis.

Results

Overall, 509 (40.9%) of women were >35 years of age, about half (52.7%) were highly educated, most (95.2%) were married/living with partner and employed (79.3%) and about half (52.9%) were primiparous. Overall, 189 (15.2%) were not born in Italy and 111 (8.9%) did not have Italian citizenship. Most women (84.2%) were highly satisfied (score ≥7/10) with the care received. Among the 61 variables explored, 46 (75.4%) were significantly associated with women’s satisfaction, 33 with higher satisfaction and 13 with lower satisfaction. Multivariate analysis largely confirmed univariate findings, with six out of eight groups of correlated variables being statistically significantly associated with women’s satisfaction. Factors most strongly associated with women’s satisfaction were ‘effective communication, involvement, listening to women’s needs, respectful and timely care’ (OR 16.84, 95% CI 9.90 to 28.61, p<0.001) and ‘physical structure’ (OR 6.51, 95% CI 4.08 to 10.40, p<0.001). Additionally, ‘victim of abuse, discrimination, aggressiveness’ was inversely associated with the wish to return to the facility or to recommend it to a friend (OR 0.35, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.70, p<0.003).

Conclusion

This study suggested that many variables are strongly associated with women’s satisfaction with care during childbirth and support the use of multiple measures to monitor the QoC at childbirth.

Keywords: quality in health care, reproductive medicine, maternal medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study exploring the association between overall maternal satisfaction and a list of other indicators of quality of care (specifically, 61 variables).

Data were collected using a field-tested, anonymous, self-administrated questionnaire based on WHO standards, presented to mothers in the postdelivery period.

Measures of ‘provision of care’, ‘experience of care’ and ‘availability of resources’, as indicated by the WHO standards, were included.

We conducted a factor analysis to evaluate the underlying structure among variables and the generated groups to perform a multivariate logistic analysis.

Although from a single facility, the study included a large sample of women (n=1244), of which 15.2% were foreign women (not born in Italy), reflecting to a large extent, the current population of women giving birth in Northeast Italy.

Introduction

The past two decades have been marked by substantive progress in reducing maternal mortality and morbidity.1 Nevertheless, according to most recent estimates, 295 000 women around the world every year die due to complications during pregnancy or childbirth.1 Most importantly, poor quality of care (QoC) is responsible for 5 million preventable deaths in low-income and middle-income countries, including half of deaths from maternal causes and 61% of neonatal conditions.2

In general, even in high-income settings in Europe, achieving high quality of healthcare is a challenge.3 Although the maternal mortality ratio was almost halved in the WHO European Region as a whole from 1990 to 2006, progress has been uneven, and striking inequalities persist between and within countries, with maternal mortality rates up to 43 times higher in some countries in the region compared with others.3 In 2013, the 53 Member States in the WHO European Region agreed on a new common policy framework—Health 2020.3 The goal of Health 2020 was to ‘significantly improve the health and well-being of populations, reduce health inequalities, strengthen public health and ensure people-centred health systems that are universal, equitable, sustainable and of high quality’. The policy framework also underscored that ‘the voice of civil society, including individuals and patient organisations and youth organisations and senior citizens, is essential to draw attention to health-damaging environments, lifestyles or products and to gaps in the quality and provision of healthcare and it is critical for generating new ideas’.

The importance of women-centred maternal care has been made explicit in several WHO documents.4–9 The recent WHO framework for maternal and newborn QoC6 identifies as a key domain—beside ‘provision of care’ and the ‘availability of physical and human resources’- the ‘experience of care’, emphasising the importance of collecting women’s views and voices.6

Based on this framework,6 WHO developed the ‘standards for improving the QoC for mothers and newborns at facility level’.7 The WHO standards promote a person-centred philosophy which implies optimising health as well as general well-being of women and newborns, and, importantly, promoting respect of patients’ rights.6 The WHO standards include over 300 quality measures and are currently the most comprehensive collection of indicators of QoC around the time of childbirth. Women’ s satisfaction with the care received is one of the WHO quality measures that should be monitored and evaluated for identifying priorities for action when aiming at improving the QoC for mothers and newborns.6 In general, satisfaction with care has frequently been used as a key indicator of patient’s experience of care.10 11

However, so far little is known on the association between women’s satisfaction with the care received during childbirth and other WHO quality measures as reported by the WHO standards.7 The WHO standards7 were developed in 2016 and so far very few evaluations using the WHO quality measures have been conducted, with most focused in Africa and Asia.12 13 In general, existing literature14 15 suggests that a positive perception of childbirth, including satisfaction with the experience of care, is multidimensional and is influenced by a variety of factors, but none explicitly evaluated the full list of variables, including both indicators of ‘provision of care’, ‘experience of care’ and ‘availability of resources’, as defined by the WHO standards.

This study aimed to explore the association between indicators of women’s satisfaction with the care received around childbirth and a list of 61 variables largely based on the WHO quality measures.

Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional observational study and is reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology checklist16 (online supplementary appendix 1).

bmjopen-2020-037063supp001.pdf (219.2KB, pdf)

Study setting and population

The study was conducted between December 2016 and September 2018 in Friuli Venezia Giulia region, Northeast Italy. The whole region has nine maternity services currently available for births and mothers are not signed to a predefined maternity service. A convenience sample of mothers was recruited and all mothers who gave birth in a public referral university hospital during the study period were invited to participate. Missing case characteristics were regularly monitored using standard operating procedures. Exclusion criteria were maternal death, perinatal death (including stillbirth), psychiatric or psychosocial problems with inability to fill in the questionnaire, age under 18 years old, language barriers, refuse to participate.

Data collection procedures

Data were collected using a field-tested, anonymous, self-administrated, questionnaire in the local language (Italian). The questionnaire included 120 questions, mostly based on WHO quality measures,7 plus sociodemographic information of women, and few additional indicators that were considered relevant to the local setting (the WHO list7 prioritises measures for low-income and middle-income settings). The selection of the variables included in the questionnaire was made based on the relevance to the local context (ie, high-income country, with low maternal and newborn mortality), the level of care provided in the facility (ie, tertiary level referral hospital) and the expected feasibility and reliability of collecting the information and was described in detail elsewhere.17

The questionnaire also included three indicators of ‘satisfaction with the care received’: (1) women’s overall satisfaction with the care received (measured on a Likert scale from 1 to 10, where 1 was minimum and 10 was maximum satisfaction), (2) women’s overall judgement of the QoC received (four possible categories: very negative, negative, neutral, positive and very positive), (3) whether the woman would wish to return to the facility or otherwise recommend it to a friend (dichotomic variable: yes or no). Procedures for the questionnaire validation will be reported on a further publication.17

The questionnaire and the overall objectives of the study were presented to the mothers in the postdelivery period, during their stay in the ward (usually less than 3 days after delivery), by trained research midwives, not involved in case management. Mothers were enrolled from Monday to Saturday, and they could return the filled questionnaires directly to the operator or in a dedicated box available in the ward 24/24 hour and 7/7 days. Data from the survey were double entered by two trained researchers on a dedicated Excel database, and any discrepancy was corrected in real time. Data on characteristics of missing cases were monitored monthly.

Type of variables

Out of the three available indicators of satisfaction with the care received, we predefined as primary-dependant variable ‘women’s overall satisfaction’, measured by a Likert scale of 1 (very low satisfaction) to 10 (maximum satisfaction), and we classified as high satisfaction a score of at least 7, out of 10. The other two available indicators—‘women’s overall judgement of the QoC received’ (positive and very positive) and whether the woman would ‘wish to return to the facility/to recommend it to a friend’—were used for secondary analysis.

As independent variables, we used 61 variables. Of these, 10 were related to maternal sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and 51 were grouped, according to WHO framework,6 in three key domains: ‘provision of care’ (16 variables), ‘experience of care’ (23 variables) and ‘availability of resources’ (12 variables). Of these 51 variables, 47 (92.2%) were WHO quality measures listed in the WHO standards.7 A detailed list of variables was provided on online supplementary appendix 2.

No variables were eliminated due to missing data, since the percentage of missing values was very low, with the highest values being around 1% for the following variables: ‘overall satisfaction’ (1.1%), ‘early breastfeeding’ (1.1%) and ‘knowledge of the respectful maternity care charter’ (1.1%) (online supplementary appendix 3).

Data analysis

We tested for independence among primary and the secondary outcomes with the Pearson χ2 and calculated the magnitude of their association with Cramer’s V (ranging from 0 to 1, with values between 0.30 and 0.49, indicating medium effect size, and values equal or bigger than 0.50, indicating large effect size).18 Univariate analyses were performed to evaluate significant associations, expressed in OR and 95% CI between the 61 independent variables (online supplementary appendix 2) and the three independent variables. We observed a high interrelations among many variables, in particular, variables in the same domain of the WHO framework,6 with the determinant of the tetrachoric correlation matrix being nearly zero, indicating multicollinearity.19–21 In this scenario, a multivariate logistic regression would have hidden the importance that each factor had had on the dependant variables.22 We conducted a factor analysis to evaluate the underlying structure among variables and consequently summarise independent variables in uncorrelated groups of variables22 23, in line with what performed in similar studies.24 Factor analysis was performed on 51 of the 61 common variables: 10 variables could not be included since they were specific of each delivery mode, and therefore answered only in subgroups of women (online supplementary appendix 2). A principal axis factoring with orthogonal varimax rotation was performed to extract factors from the tetrachoric correlation matrix.25 To identify the number of factors to include, we used as first step the Kaiser’s rule,22 23 that is, all eigenvalues over one were retained. On the factors extracted, other two criteria were applied: the percentage of variance criterion (ie, only factor solutions that account for at least 60% of the total variance can be considered satisfactory) as well as interpretability of factor structure (ie, whether the variables in each group were conceptually linked each other).22 Finally, we used the groups generated by the factor analysis to perform a multivariate logistic model evaluating the association of each factor with the dependent variables. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata V.14 and R software.

Ethical considerations

Participants to the survey were informed about the objectives and methods of the study, including their rights in declining participation and signed an informed consent before responding to the questionnaires. Anonymity in data collection during the survey phase was ensured by not collecting any information that could disclose participants’ identity.

Patient and public involvement

A group of voluntary mothers were involved in the development and construct validation of the questionnaire. Inputs received from mothers were used to revise the content of the questionnaire, including reducing its length to improve acceptability.

Results

Women’s characteristics

Overall, 1244 mothers answered the questionnaire (52% of eligible sample) (online supplementary appendix 4). Characteristics of mothers are reported in table 1. Two-fifth (40.9%) of women had more than 35 years, about half (52.7%) were highly educated (college or above), most (95.2%) were married or living with a partner and employed (79.3%) and about half (52.9%) were primiparous. Overall, about one-sixth (15.2%) were not born in Italy and 111 (8.9%) did not have an Italian citizenship. There were no significant differences between mothers who answered the questionnaire and those who did not (online supplementary appendix 5). The prevalence of women highly satisfied (score ≥7) was 84.2%.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the population

| N (N=1244) | % | |

| Age | ||

| <35 years old | 735 | 59.1 |

| ≥35 years old | 509 | 40.9 |

| High education (college or above) | ||

| No | 582 | 46.8 |

| Yes | 655 | 52.7 |

| Born in Italy | ||

| Yes | 1051 | 84.5 |

| No | 189 | 15.2 |

| Citizenship | ||

| Italian | 1124 | 90.3 |

| Not Italian | 111 | 8.9 |

| Occupational status | ||

| Employed | 987 | 79.3 |

| Non employed | 251 | 20.2 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single/other | 52 | 4.2 |

| Married/living with a partner | 1184 | 95.2 |

| Parity | ||

| Primiparous | 658 | 52.9 |

| Multiparous | 586 | 41.1 |

| Multiple pregnancies | ||

| Yes | 21 | 1.7 |

| No | 1223 | 98.3 |

| Women’s overall satisfaction | ||

| Score ≥7 | 1047 | 84.2 |

| Score <7 | 183 | 14.7 |

| Women’s judgement of the QoC received | ||

| Positive | 1112 | 89.4 |

| Negative | 128 | 10.3 |

| Recommend the facility to a friend | ||

| Yes | 987 | 79.3 |

| No | 253 | 20.3 |

QoC, quality of care

Association among different indicators of women satisfaction

A significant association was found between all three variables of satisfaction and the estimated effect size of the association was medium–high for all indicators, as follows: between ‘woman’s overall satisfaction’ and ‘women’s positive judgement of the QoC received’ (χ2 p<0.001, Cramer’s V=0.44); between ‘woman’s overall satisfaction’ and ‘to wish to return to the facility/to recommend it to a friend’ (χ2 p<0.001, Cramer’s V=0.45); between ‘women’s positive judgement of the QoC received’ and ‘to wish to return to the facility/to recommend it to a friend’ (χ2 p<0.001, Cramer’s V=0.52).

Univariate analysis

The following paragraph reports key results on the association between ‘women’s overall satisfaction’ and the other 61 variables of QoC. Additional detailed findings are provided in online supplementary appendix 6.

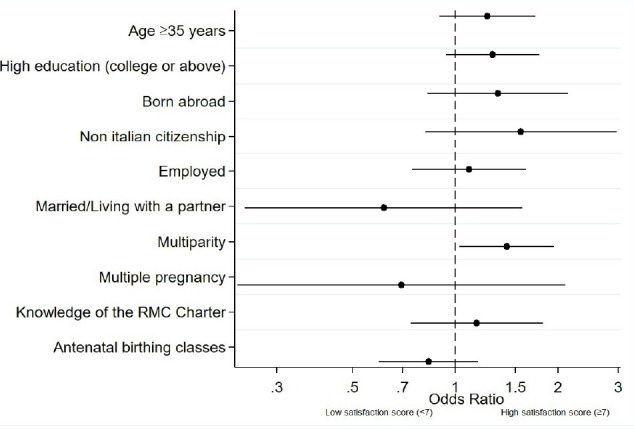

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

A significant association was identified between multiparity and higher women’s overall satisfaction (OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.95, p=0.033). No other significant association was found among sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of women and ‘women’s overall satisfaction’ (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Association between ‘women’s overall satisfaction’ and sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. RMC, respectful maternity care.

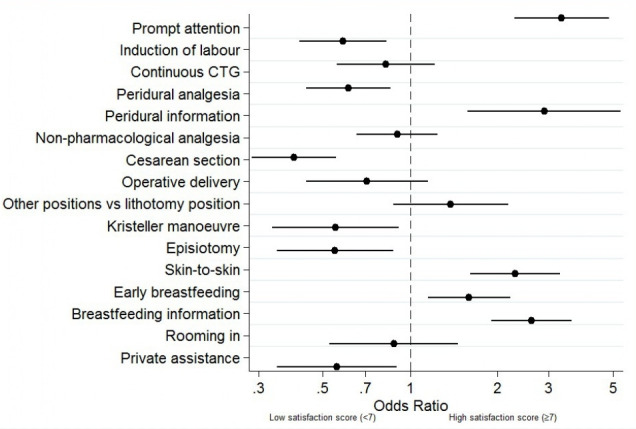

Indicators of provision of care

Among the 16 indicators of provision of care, 5 were significantly associated with high ‘women’s overall satisfaction’, while 6 were significantly associated with lower overall satisfaction (figure 2). The variables more strongly associated with high ‘women’s overall satisfaction’ were: receiving prompt attention (OR 3.33, 95% CI 2.29 to 4.84, p<0.001), receiving information on peridural analgesia (OR 2.90, 95% CI 1.58 to 5.31, p<0.001), receiving information on breastfeeding (OR 2.62, 95% CI 1.91 to 3.61, p<0.001) and skin to skin (OR 2.30, 95% CI 1.61 to 3.28, p<0.001). Overall, two variables not based on WHO quality measures, ‘induction of labour’ and ‘private assistance’, were significantly associated with a low maternal satisfaction. The variable more strongly associated with lower satisfaction was caesarean section (OR=0.40, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.56).

Figure 2.

Association between ‘women’s overall satisfaction’ and indicators of provision of care. CTG, cardiotocography. All variables were WHO quality measures, except for ‘induction of labour’ and ‘private assistance’, which resulted significantly associated with a low maternal satisfaction.

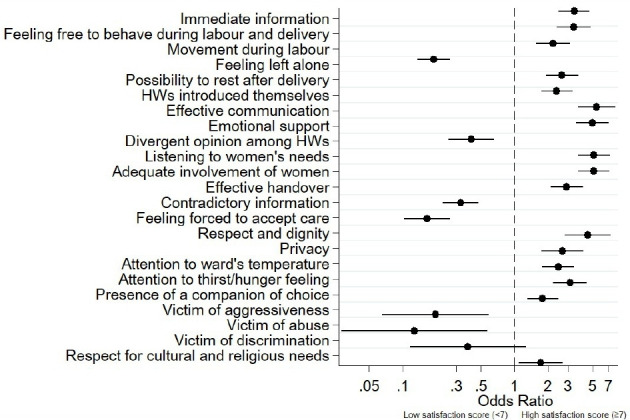

Indicators of experience of care

Among the 23 indicators of experience of care, 16 were positively associated with high ‘women’s overall satisfaction’, while 6 were significantly associated with lower overall satisfaction (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Association between ‘women’s overall satisfaction’ and indicators of experience of care. HWs, health workers.

The variables more strongly associated with high ‘women’s overall satisfaction’ were effective communication (OR 5.47, 95% CI 3.73 to 8.04, p<0.001), active listening to women’s needs (OR 5.14, 95% CI 3.69 to 7.18, p<0.001), adequate involvement of women in the process of care (OR 5.14, 95% CI 3.69 to 7.16, p<0.001) and receiving emotional support (OR 5.00, 95% CI 3.56 to 7.02, p<0.001).

The variables more strongly associated with lower overall satisfaction were feeling victim of aggressiveness (OR 0.20, 95% CI 0.007 to 0.59, p<0.001), feeling left alone (OR 0.19, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.27, p<0.001), feeling forced to accept care (OR 0.17, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.27, p<0.001) and feeling victim of abuse (OR 0.13, 95% CI 0.003 to 0.58, p= 0.007).

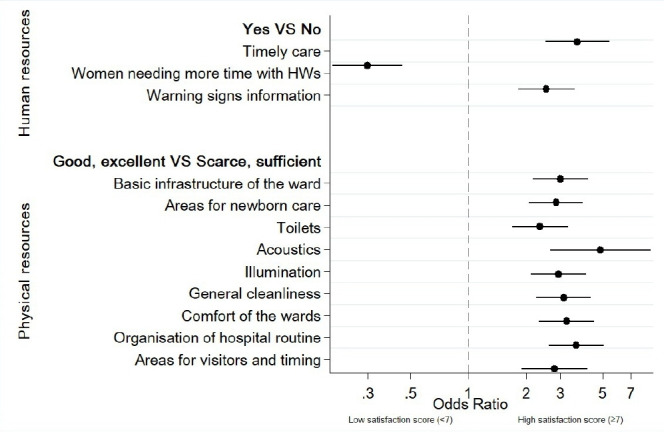

Indicators of availability of resources

Two indicators of human resources out of three and all nine indicators of availability of physical resources were positively associated with women’s high satisfaction (figure 4), with the one more strongly associated being good acoustic in the wards with reduction of external noises (OR 4.85, 95% CI 2.66 to 8.86, p<0.001). The only variable associated with lower overall satisfaction was women’s need of more time with health workers (OR 0.30, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.46, p<0.001). Overall, two variables not based on WHO quality measures, ‘organisation of hospital routine’ (timings of follow-up visits, medications, etc) and ‘areas for visitors and timing’, which resulted significantly associated with a high maternal satisfaction.

Figure 4.

Association between ‘women’s overall satisfaction’ and indicators of availability ofresources. HWs, health workers. All variables were WHO quality measures, except for ‘organisation of hospital routine’ (timings of follow-up visits, medications, etc) and ‘areas for visitors and timing’, which resulted significantly associated with a high maternal satisfaction.

Factor analysis

According to the Kaiser’s rule,21 22 the predefined percentage of variance and interpretability criteria, an eight-factor solution, were considered the most suitable to represent the structure of our data, accounting for 61% of the total variance. Detailed results of the rotated factor solution and the list of variables in each consequent group are provided in online supplementary appendix 7.

Multivariate analysis

From the multivariate logistic regression, six out of eight factors identified by factor analysis resulted as being independently associated with higher ‘women’s satisfaction’ (table 2). The factors more strongly associated were ‘effective communication, involvement, listening to women’s needs, respectful and timely care’ (OR 16.84, 95% CI 9.90 to 28.61, p<0.001) and ‘physical structure’ (OR 6.51, 95% CI 4.08 to 10.40, p<0.001).

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis exploring the association between group of variables generated by factorial analysis and ‘women’s overall satisfaction’

| Factors (group of variables) | Variables included* | Factor loading |

Adjusted OR | 95% CI | P value |

| Effective communication, involvement, listening to women’s needs, respectful and timely care | Effective communication (E) | 0.84 | 16.84 | 9.90 to 28.61 | <0.001 |

| Adequate involvement of women (E) | 0.79 | ||||

| Listening to women’s needs (E) | 0.79 | ||||

| Respect and dignity (E) | 0.72 | ||||

| Emotional support (E) | 0.72 | ||||

| Timely care (R) | 0.7 | ||||

| Effective handover (E) | 0.66 | ||||

| Feeling left alone (E) | −0.62 | ||||

| Women needing more time with HWs (R) | −0.59 | ||||

| Feeling forced to accept care (E) | −0.57 | ||||

| Privacy (E) | 0.55 | ||||

| Immediate information (E) | 0.53 | ||||

| Prompt attention (P) | 0.53 | ||||

| Divergent opinion among HWs (E) | −0.5 | ||||

| Heath workers introduced themselves (E) | 0.45 | ||||

| Contradictory information (E) | −0.4 | ||||

| Physical structure | General comfort of the wards (R) | 0.88 | 6.51 | 4.08 to 10.40 | <0.001 |

| Basic infrastructure of the ward (R) | 0.87 | ||||

| Toilets (R) | 0.85 | ||||

| Areas for newborn care (R) | 0.84 | ||||

| General cleanliness (R) | 0.79 | ||||

| Illumination (R) | 0.77 | ||||

| Acoustics (R) | 0.73 | ||||

| Organisation of hospital routine (R)† | 0.71 | ||||

| Areas for visitors and timing (R)† | 0.71 | ||||

| Possibility to rest after delivery (E) | 0.4 | ||||

| Victim of abuse, discrimination, aggressiveness | Victim of abuse (E) | 0.85 | 1.08 | 0.55 to 2.15 | 0.811 |

| Victim of discrimination (E) | 0.78 | ||||

| Victim of aggressiveness (E) | 0.72 | ||||

| Multiple pregnancies (S) | −0.61 | ||||

| Good neonatal practices | Skin-to-skin (P) | 0.87 | 1.82 | 1.13 to 2.30 | 0.013 |

| Early breastfeeding (P) | 0.83 | ||||

| Caesarean section (P) | −0.75 | ||||

| Rooming in (P) | 0.72 | ||||

| Women characteristics | Italian citizenship (S) | 0.84 | 0.81 | 0.47 to 1.42 | 0.479 |

| Born in Italy (S) | 0.79 | ||||

| Occupation status—employed (S) | 0.7 | ||||

| Age ≥35 years (S) | 0.52 | ||||

| Marital status—married/living with partner (S) | 0.35 | ||||

| High education level (S) | 0.35 | ||||

| Antenatal groups and multiparity | Multiparity (S) | 0.8 | 1.92 | 1.22 to 3.01 | 0.005 |

| Antenatal birthing classes (S) | −0.75 | ||||

| Mode of birth, attention to women comfort and partnership in labour | Vaginal operative delivery (P) | 0.6 | 1.66 | 1.02 to 2.70 | 0.04 |

| Attention to ward’s temperature (E) | 0.51 | ||||

| Presence of a companion of choice (E) | 0.47 | ||||

| Attention to thirst/hunger feeling (E) | 0.4 | ||||

| Information on danger signs and women rights | Warning signs information (R) | 0.52 | 1.84 | 1.20 to 2.83 | 0.005 |

| Respect for cultural and religious needs (E) | −0.47 | ||||

| Breastfeeding information (P) | 0.46 | ||||

| Knowledge of the respectful maternity care charter (S) | 0.37 |

*Only variables with factor loading >0.3, in a descending order of contribution to the factor, are reported. Each variable is reported once, only in the factor with higher contribution

†Additional variables for availability of resources (not based on WHO quality measures).

CS, caesarean section; (E), experience of care; HW, health worker; (P), provision of care; (R), availability of resources; RMC, respectful maternity care; (S), sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

Analyses of secondary indicators of satisfaction with care

In the univariate analysis, the association between independent variables and the secondary dependant variables (ie, ‘women’s positive judgement of the QoC received’; ‘wish to return to the facility/to recommend it to a friend’) were very much in line with the findings of the analysis on the primary variable (ie, women’s overall satisfaction), with only minor differences (online supplementary appendix 8). Specifically, nine variables that significantly associated with ‘women’s overall satisfaction’ were not significantly associated with ‘women’s positive judgement of the QoC received’ (these variables were parity, peridural analgesia, caesarean section, Kristeller manoeuvre, episiotomy, skin-to-skin, early breastfeeding, private assistance, respect for cultural and religious needs). Similarly, five did not associate with ‘wish to return to the facility/to recommend it to a friend’ (these variables were parity, continuous cardiotocography, peridural analgesia, Kristeller manoeuvre and episiotomy).

In multivariate analysis, three factors (‘effective communication, involvement, listening to women’s needs, respectful and timely care’ (OR=41.48), ‘physical structure’ (OR=20.69) and ‘antenatal groups and multiparity’ (OR=2.44)) were significantly associated with ‘women’s positive judgement of QoC received’, while five factors (‘effective communication, involvement, listening to women’s needs, respectful and timely care’ (OR=32.75), ‘physical structure’ (OR=15.70), ‘victim of abuse, discrimination, aggressiveness’ (OR=0.35), ‘antenatal groups and multiparity’ (OR=1.65), ‘mode of birth, attention to women comfort and partnership in labour’ (OR=2.26)) were significantly associated with ‘wish to return to the facility/to recommend it to a friend’ (online supplementary appendices 9 and 10).

Discussion

This study explored the association between women’s high satisfaction with care received during childbirth and 61 other variables, 10 maternal characteristics and 51 other variables related to QoC, most (92.2%) corresponding to WHO quality measures.7 Overall, the study shows that, while maternal characteristics were poorly associated with women’s satisfaction, many aspects of QoC were significantly associated with it. Specifically, in univariate analysis, 45/51 (88%) indicators of QoC were statistically significantly associated with satisfaction with care, with 32 associated with higher satisfaction and 13 with lower satisfaction. The strongest positive associations were found with effective communication (OR=5.47), while the strongest negative associations were found with caesarean section (OR=0.36). Many variables strongly correlated with each other. Results of multivariate analysis, using groups of variables generated by factorial analysis, largely confirmed these findings, with six out of eight groups of correlated variables statistically significantly associated with women’s high satisfaction. The factors more strongly associated with women’s satisfaction were ‘effective communication, involvement, listening to women’s needs, respectful and timely care’ (OR=16.84) and ‘physical structure’ (OR=6.51). These two groups alone included over half of the total variables. Additionally, ‘victim of abuse, discrimination, aggressiveness’ was inversely associated with the wish to return to the facility or to recommend it to a friend (OR 0.35, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.70, p<0.003).

This is the first study reporting on the association between satisfaction with care received during childbirth and a list of WHO quality measures. Findings of the study overall are in line with the existing literature, suggesting that a positive perception of childbirth, including satisfaction with the experience of care, is multidimensional and is influenced by a variety of factors, such as mode of delivery;2 14 26 sense of control during birth;27 28 quality of relationship with caregivers including good communication, participation in decision-making,27–29 emotional support27–29 and continuous support provided by a companion of choice.30–33 Notably, studies in both low-income and middle-income countries34 35 and high-income settings36 37 have suggested that overall women’s satisfaction can be affected by many dimensions of the QoC, across structure, process and outcomes.

Interestingly, studies in both low-income35 and high-income countries36–38 suggested that when women evaluate their childbirth experiences, process of care dominated the determinants of maternal satisfaction.35 38 In particular, factors related to the ‘experience of care’, such as the amount of support from caregivers, the quality of the caregiver–patient relationship and involvement in decision-making, together with personal expectations, appear to be so important that they override the influences of many other factors, including sociodemographic characteristics of women such as age, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, childbirth preparation and medical interventions.38 This is in line with the findings of our study, where maternal characteristics were poorly associated with women’s satisfaction, with the exception of multiparity, whose strong association could be due to a ‘contrast effect’ (enhancement, relative to normal, of a perception as a result of successive or simultaneous exposure to a situation).39 40 Previous childbirth experiences of multiparous women may had positively influenced their current level of satisfaction with care received.

The importance of ‘experience of care’ may also explain why women’s satisfaction with care has been reported as substandard in settings, such as Scandinavian countries, where resources are available, organisation of care is generally good, and evidence-based practices are overall widespread.36 37 Clearly, these aspects of care may contribute but per se are not enough to ensure a good ‘experience’ of childbirth. Several authors have called for the need for a global cultural shift in the obstetric field and have underscored the importance of setting professional standards, including standards on skills such as effective communication and prevention of mistreatment and abuse, in order to fulfil the goal of providing patient-centred care at childbirth.41 42

Some of the findings of multivariate analysis—such as the lack of a significant association between ‘victim of abuse, discrimination, aggressiveness’ and maternal satisfaction, may be explained by the small sample of women reporting these indicators and should be further evaluated in other studies.

Overall, this study, together with the existing literature,26–38 delivers an important message to policymakers and to engaged maternal care professionals: many aspects of care, and in particular the ‘experience of care’, contribute to a certain extent to the overall satisfaction of women with the care received. Therefore, many indicators of QoC should be routinely monitored and actively improved if found to be substandard. Measuring women’s satisfaction alone may not provide a comprehensive picture of the QoC received, nor explore important underlying determinants of QoC. Only more detailed evaluations of a set of multiple quality indicators can provide actionable information for improving QoC. Interviewing mothers has been a WHO recommendation for the review of maternal near-miss cases for a long time and has shown a significant effect in reducing maternal mortality.43 Currently, WHO, in agreement with several other agencies and bodies, recommends to routinely explore several aspects of women’s ‘experience of care’ in order to identify actions to improve the quality of maternal and newborn care at the facility level.6 7

We acknowledge that this is single-centre study, and data are not directly generalisable to other contexts. However, the study enrolled a relatively large sample of women that generally reflects the current population of women giving birth in Northeast Italy, in particular, in the Friuli Venezia Giulia Region where the study took place, and, in particular, in relation to the prevalence of foreign women (15.2%).44 More studies should be conducted to explore factors associated with poor women’s satisfaction with care at childbirth in different settings, and, most importantly, on how to improve it.

Overall, the study identified four variables—‘induction of labour’, ‘private assistance’, ‘organisation of hospital routine’ (timings of follow-up visits, medications, etc) and ‘areas for visitors and timing’- currently not listed among the WHO quality measures7 and significantly associated with maternal satisfaction. Although WHO standards include many indicators, they have not been developed specifically for high-income countries, and this may explain why some variables, such as the one listed above, are missing. More studies should further explore other factors associated with women satisfaction with care at childbirth in high-income countries.

Conclusion

This study suggested that many variables are strongly associated with women’s satisfaction with care during childbirth and support the recommendation of using multiple measures to monitor the QoC at childbirth in high-income settings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of mothers that participate in the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: ML conceived the paper in discussion with IM, CS and EPV. IM analysed data. ML drafted the initial manuscript and all authors reviewed/edited the manuscript for critically important intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by the Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS Burlo Garofolo.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the Independent Ethical Review Board of the IRCCS Burlo (protocol number: 617/2016).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request. All details of the analyses conducted are provided within the manuscript. Additional details can be provided by contacting the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

References

- 1.UNFPA, World Health Organization, UNICEF, World Bank Group, The United Nations Population Division . Trends in maternal mortality: 2000 to 2017. estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, world bank group and the United nations population division. Available: https://www.unfpa.org/featured-publication/trends-maternal-mortality-2000-2017 [Accessed 16 Jan 2020].

- 2.Kruk ME, Gage AD, Joseph NT, et al. Mortality due to low-quality health systems in the universal health coverage era: a systematic analysis of amenable deaths in 137 countries. Lancet 2018;392:2203–12. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31668-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization Health 2020 a European policy framework and strategy for the 21st century. World Health organization, Copenhagen, 2013. Available: http://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/abstracts/health-2020.-a-european-policy-framework-and-strategy-for-the-21st-century-2013 [Accessed 16 Jan 2020].

- 4.World Health Organization Beyond the numbers: reviewing maternal deaths and complications to make pregnancy safer. World Health organization, Geneva, 2004. Available: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2004/9241591838.pdf?ua=1 [Accessed 16 Jan 2020].

- 5.World Health Organization Global strategy for women's, children's and adolescent's health 2016-2030. Available: http://www.who.int/life-course/partners/global-strategy/global-strategy-2016-2030/en/ [Accessed 16 Jan 2020].

- 6.Tunçalp Ӧ, Were WM, MacLennan C, et al. Quality of care for pregnant women and newborns-the WHO vision. BJOG 2015;122:1045–9. 10.1111/1471-0528.13451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities. Geneva: World Health organization, 2016. Available: https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/improving-maternal-newborn-care-quality/en [Accessed 16 Jan 2020].

- 8.World Health Organization The prevention and elimination of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth. Geneva: World Health organization, 2014. Available: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/maternal_perinatal/statement-childbirth/en/ [Accessed 16 Jan 2020].

- 9.Oladapo OT, Tunçalp Ö, Bonet M, et al. WHO model of intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience: transforming care of women and babies for improved health and wellbeing. BJOG 2018;125:918–22. 10.1111/1471-0528.15237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conesa Ferrer MB, Canteras Jordana M, Ballesteros Meseguer C, et al. Comparative study analysing women's childbirth satisfaction and obstetric outcomes across two different models of maternity care. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011362. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alfaro Blazquez R, Corchon S, Ferrer Ferrandiz E. Validity of instruments for measuring the satisfaction of a woman and her partner with care received during labour and childbirth: systematic review. Midwifery 2017;55:103–12. 10.1016/j.midw.2017.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manu A, Arifeen S, Williams J, et al. Assessment of facility readiness for implementing the WHO/UNICEF standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities - experiences from UNICEF's implementation in three countries of South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:531. 10.1186/s12913-018-3334-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bohren MA, Mehrtash H, Fawole B, et al. How women are treated during facility-based childbirth in four countries: a cross-sectional study with labour observations and community-based surveys. Lancet 2019;394:1750–63. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31992-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carquillat P, Boulvain M, Guittier M-J. How does delivery method influence factors that contribute to women's childbirth experiences? Midwifery 2016;43:21–8. 10.1016/j.midw.2016.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smarandache A, Kim THM, Bohr Y, et al. Predictors of a negative labour and birth experience based on a national survey of Canadian women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:114. 10.1186/s12884-016-0903-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.STROBE Statement Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology, 2009. Available: https://www.strobe-statement.org/index.php?id=strobe-home [Accessed 16 Jan 2020].

- 17.Lazzerini M, Valente EP, Covi B, et al. Use of WHO standards to improve quality of maternal and newborn hospital care: a study collecting both mothers' and staff perspective in a tertiary care hospital in Italy. BMJ Open Qual 2019;8:e000525. 10.1136/bmjoq-2018-000525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen J. Chi-Square Tests for Goodness of Fit and Contingency : Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd edn Routledge, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blalock HM. Correlated independent variables: the problem of Multicollinearity. Social Forces 1963;42:233–7. 10.2307/2575696 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kleinbaum DG, Klein M. Additional Modeling Strategy Issues : Logistic regression, statistics for biology and health. Atlanta, GA: Springer Science+Business Media, 2010: 241–300. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dormann CF, Elith J, Bacher S, et al. Collinearity: a review of methods to deal with it and a simulation study evaluating their performance. Ecography 2013;36:27–46. 10.1111/j.1600-0587.2012.07348.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, et al. Exploratory Factor Analysis : Multivariate data analysis. 7th edn London: Pearson Education Limited, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams B, Onsman A, Brown T. Exploratory factor analysis: a five-step guide for novices. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine 2010;8 10.33151/ajp.8.3.93 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keller AC, Bergman MM, Heinzmann C, et al. The relationship between hospital patients' ratings of quality of care and communication. Int J Qual Health Care 2014;26:26–33. 10.1093/intqhc/mzt083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nestler S. A Monte Carlo study comparing Piv, ULS and DWLS in the estimation of dichotomous confirmatory factor analysis. Br J Math Stat Psychol 2013;66:127–43. 10.1111/j.2044-8317.2012.02044.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bossano CM, Townsend KM, Walton AC, et al. The maternal childbirth experience more than a decade after delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:342.e1–342.e8. 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.04.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nilsson C, Bondas T, Lundgren I. Previous birth experience in women with intense fear of childbirth. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2010;39:298–309. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2010.01139.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elmir R, Schmied V, Wilkes L, et al. Women's perceptions and experiences of a traumatic birth: a meta-ethnography. J Adv Nurs 2010;66:2142–53. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05391.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stankovic B. Women's experiences of childbirth in Serbian public healthcare institutions: a qualitative study. Int J Behav Med 2017;24:803–14. 10.1007/s12529-017-9672-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larkin P, Begley CM, Devane D. 'Not enough people to look after you': an exploration of women's experiences of childbirth in the Republic of Ireland. Midwifery 2012;28:98–105. 10.1016/j.midw.2010.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macpherson I, Roqué-Sánchez MV, Legget Bn FO, et al. A systematic review of the relationship factor between women and health professionals within the multivariant analysis of maternal satisfaction. Midwifery 2016;41:68–78. 10.1016/j.midw.2016.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gürber S, Bielinski-Blattmann D, Lemola S, et al. Maternal mental health in the first 3-week postpartum: the impact of caregiver support and the subjective experience of childbirth - a longitudinal path model. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2012;33:176–84. 10.3109/0167482X.2012.730584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bohren MA, Berger BO, Munthe-Kaas H, et al. Perceptions and experiences of labour companionship: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;3:CD012449. 10.1002/14651858.CD012449.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohamed R, Fahmy FF, Senanayake H, et al. Correlation among experience of person-centered maternity care, provision of care and women’s satisfaction: cross sectional study in Colombo, Sri Lanka. BMJ Open. In Press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Srivastava A, Avan BI, Rajbangshi P, et al. Determinants of women's satisfaction with maternal health care: a review of literature from developing countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:97. 10.1186/s12884-015-0525-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilde-Larsson B, Sandin-Bojö A-K, Starrin B, et al. Birthgiving women's feelings and perceptions of quality of intrapartal care: a nationwide Swedish cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs 2011;20:1168–77. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03393.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henriksen L, Grimsrud E, Schei B, et al. Factors related to a negative birth experience - A mixed methods study. Midwifery 2017;51:33–9. 10.1016/j.midw.2017.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hodnett ED. Pain and women's satisfaction with the experience of childbirth: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;186:S160–72. 10.1067/mob.2002.121141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Palmer JK, Gore JS. A theory of contrast effects in performance appraisal and social cognitive judgments. Psychol Stud 2014;59:323–36. 10.1007/s12646-014-0282-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Javidmehr M, Ebrahimpour M. Performance appraisal bias and errors: the influences and consequences. IJOL 2015;4:286–302. 10.33844/ijol.2015.60464 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coast E, Jones E, Lattof SR, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to provide culturally appropriate maternity care in increasing uptake of skilled maternity care: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan 2016;31:1479–91. 10.1093/heapol/czw065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Akileswaran CP, Hutchison MS. Making room at the table for obstetrics, midwifery, and a culture of Normalcy within maternity care. Obstet Gynecol 2016;128:176–80. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lazzerini M, Richardson S, Ciardelli V, et al. Effectiveness of the facility-based maternal near-miss case reviews in improving maternal and newborn quality of care in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019787. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.nascita E, CeDAP ilR. Direzione Generale DELLA Digitalizzazione, del Sistema Informativo Sanitario E DELLA Statistica – Ufficio di statistica Rome, Italy, 2015, 2015. Available: http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/news/p3_2_1_1_1.jsp?lingua=italiano&menu=notizie&p=dalministero&id=3446 [Accessed 16 Jan 2020].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-037063supp001.pdf (219.2KB, pdf)