Highlights

-

•

Extra articular osteochondromatosis is rare and scarcely reported around the ankle joint.

-

•

Due to the subtle clinical and radiological presentation of SC they often lead to a diagnostic challenge.

-

•

Higher degree of suspicion enables early diagnosis, thereby preventing both morbidity and inadequate treatment.

-

•

Although MRI plays a key role in deciding the extent of the surgery, confirmation can be made only with histopathology.

-

•

Long term follow up is mandatory considering both the risk of local recurrence and rare malignant transformation.

Keywords: Synovial chondromatosis, Synovial osteochondromatosis, Extra synovial, Extra articular, Ankle, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Synovial chondromatosis (SC) is a relatively common benign condition of the synovial joint characterized by the formation of cartilaginous nodules in synovium. However, extra articular osteochondromatosis is rare and only few have been reported around the ankle joint. We have reported such a presentation and have reviewed the literature extensively.

Presentation of case

We present a 26 year old male patient with a painless swelling over the lateral aspect of his left ankle. He was subjected to clinical and radiological examination which revealed a firm to hard swelling around the lateral malleolus and a lobulated juxtacortical cystic lesion with calcification. He underwent a surgical excision and subsequent histopathology was suggestive of SC.

Discussion

The subtle clinical and radiological presentation of SC can lead to both a delay in the diagnosis and a diagnostic dilemma if suspicion is low. Early meticulous diagnosis and management can curtail morbidity.

Conclusion

The degree of suspicion needs to be high to diagnose the condition early to prevent both morbidity and inadequate treatment. Histopathological corroboration is needed to rule out uncommon but possible malignant transformation, notably in long standing cases.

1. Introduction

Extraarticular (EA) SC is an uncommon and benign disease [1,2] with the prevalence of approximately 1 per 100,000 [3]. SC is considered to involve metaplastic change in the connective tissues within synovial membranes leading to chondroid tissue formation [[2], [3], [4], [5], [6]], subsequent calcification and ossification of these cartilage lumps which may detach to form loose bodies [7], if inside joints, results in damage to the articular cartilage. The aetiology remains unknown and has a male preponderance, [1,3,4] usually occurring between the third and fifth decade of life [1,3,7,8] and rarely poly-articular [[2], [3], [4]]. SC can be primary, also known as Reichel’s disease or the more common secondary type due to degenerative changes from intraarticular (IA) pathology [3], trauma episodes, neuropathic arthritis and osteochondritis dissecans [9]. In general, EA SC possesses a diagnostic challenge having to rule out chondrosarcoma with a similar histopathological and radiological appearance in early stages [2,6,10]. There are very few reports of EA SC around the ankle [1,3,4]. We report such a case managed at our university hospital and review the relevant literature in accordance with SCARE guidelines 2018 [11].

2. Case report

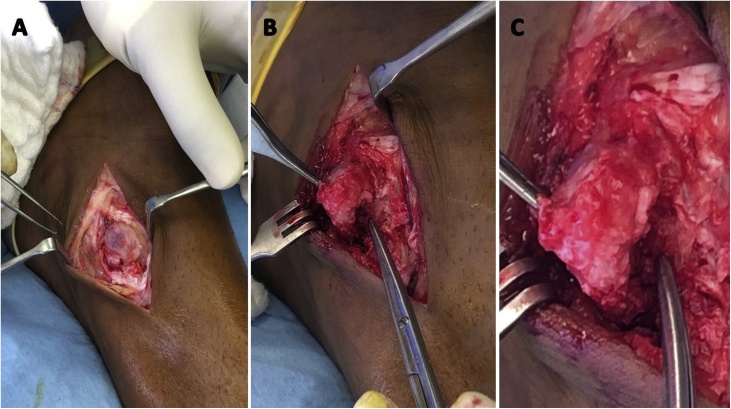

A 26 years old male without pre-existing co-morbidities or familial history presented with complaints of swelling on the lateral aspect of the left ankle since 8 months. The swelling was slowly growing in size over time, but remained pain-free despite hindrance with wearing shoes and closed foot-wear. He denied history of trauma, constitutional symptoms or involvement of other joints. On examination of the left ankle joint, there was an ovoid, non-tender swelling of 3 × 2 × 1 cm proximal to the lateral malleolus. The swelling did not reveal warmth or signs of inflammation, firm to hard in consistency, non-transilluminant, without bruit, and with pinch-able overlying skin. Ankle range of movement was normal without palpable crepitus or loose bodies in the joint. There was no neurovascular compromise. Antero-posterior and lateral radiographs of the ankle revealed a soft tissue swelling over the lateral malleolus, without any degenerative changes (Fig. 1A). Magnetic resonance imaging showed lobulated juxta-cortical cystic lesion in the anterolateral aspect of the ankle joint with calcification and minimal wall enhancement (Fig. 1B). A differential diagnosis of a complicated synovial cyst with inflammatory or traumatic changes was made. Patient was counselled, taken up for an excision biopsy, performed by the Primary and third authors. Intra-operatively a large encapsulated firm to hard lesion measuring 3 × 2 × 1 cm without communication to the joint or attachment to the bone was excised and sent for examination (Fig. 2). The histopathological finding was that of a benign lesion composed of lobules of mature hyaline cartilage with foci of ossification, with surrounding fibrosis and synovial tissue without any evidence of malignancy, hence suggestive of synovial chondromatosis (Figs. 3, 4). The patient’s postoperative period was uneventful without any additional interventions. He recovered well without any recurrence until the last clinical and radiological follow-up at two years.

Fig. 1.

A. Plain radiograph of left ankle AP and B. lateral view C. MRI T2 image in coronal section showing high signal small (1.7 × 1.4 × 1 cm) lobulated juxtacortical cystic lesion in the anterolateral aspect of the ankle region, superficial to the distal fibula with small subperiosteal component and relative thinning of fibula. Incidental finding of simple calcaneal bone cyst also noted.

Fig. 2.

A. Intra – operative images after skin and subcutaneous dissection B. Meticulous en mass dissection removing adhesions C. showing the continuity with the underlying tendon sheath.

Fig. 3.

Histopathology showing lobules of mature hyaline cartilage with foci of ossification.

Fig. 4.

Histopathology showing cartilage with ossification and surrounding fibrosis.

3. Discussion

A search in PUBMED for a combination of the keywords “extra-articular” and “synovial osteochondromatosis/synovial chondromatosis” and “ankle” resulted in 13 articles, Of these, ten articles which had reported on EA SC around the ankle, available in English literature were reviewed and summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of reports on extra-articular synovial osteochondromatosis [13].

| S No | Author/year | Age/Gender | Presentation | Radiology | Treatment | Biopsy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Franklin et al./1977 | 45/F | Recurrent swelling in anterior aspect of ankle | Radiograph - Irregularity in cortex of distal end of tibia and soft tissue swelling with calcification | Open exploration and excision | Lobules of cartilage within synovial tissue without bony invasion |

| 2 | Thomas et al./1980 | 47/F | Recurrent mass on the anterior aspect of the ankle | Radiograph - Soft tissue mass on anterior part of tibia with irregular margin and destruction of anterior cortex; Recurrence after 2 years - X ray revealed extensive lesion involving the anterior aspect of distal end tibia with intra - medullary extension | Subtotal excision biopsy Recurrence: B/K amputation | Initial HPE - Lobules of cartilage cells with intervening acellular stroma; HPE of recurrence - Two distinct patterns: 1) chondrocyte cluster with intervening acellular stroma, 2) sheets of cartilage cells with moderately atypical nuclei |

| 3 | Tibrewal et al./1995 | 44/F | Painful soft tissue mass over anterolateral aspect of right ankle | Radiograph - Lytic area in the lower tibia & fibula with scalloping of margin, extending to articular surface, soft tissue mass around ankle without calcification; CT - Well defined soft tissue mass with calcification and erosion of tibiofibular syndesmosis | Open excision | Lobules of cartilage with covering of hyaline material and synovium along with focal osteoid formation, some enlarged chondrocyte nuclei without atypia |

| 4 | Van et al./2006 | 56/F | Mass in the posterior aspect of left ankle for 2 years, pain for 6 months and increasing in size for 2 months | Radiograph - soft tissue density with a circumscribed mass posterior to ankle & subtalar joint; MRI - multiple cystic appearing masses along tibiotalar joint extending cephalad along the posterior margin of FHL. Anterior extension to talus through the sinus tarsi, laterally to anterior and medial margin of peroneal tendon, no ossification | Open excision | Chondrocyte metaplasia with cartilaginous nodules within synovial membrane |

| 5 | Kim et al./2013 | 32/M | Painful swelling left subtalar region laterally | Radiograph, CT - huge, rounded, finely stippled, calcified mass with radio-opaque bodies lateral to subtalar joint. MRI - T2 weighted high signal intensity compatible with calcification and ossification with hypointense septa | Open excision | Nodules of mature hyaline cartilage located under a layer of synovial membrane, with central ossification and osteoblastic rimming |

| 6 | Lui et al./2014 | 55/F | Lump over the dorsum of the foot with pain and gradually increasing size | MRI - Cyst around the EDL tendon with multiple calcified masses | EDL tendoscopy with synovectomy, ankle arthroscopy with removal of loose body & debridement | Cartilaginous nodules with inflamed synovial tissue |

| 7 | Nichelle et al./2015 | 17/F | Intermittent swelling and discomfort posterior to left medial malleolus | Radiograph - Soft-tissue density obscuring Kagers fat pad; MRI - distension of FHL tendon sheath with innumerable non ossified cartilage bodies measuring 1−4mm | open excision | Nodules rich in chondroid matrix with reactive chondrocytes |

| 8 | Pinter et al./2017 | 48/M | Painful mass over the posteromedial aspect of right ankle | Radiograph - Mass without calcification; MRI - 4 cm irregular mass involving FDL, FHL and PT | open excision | Cluster of clonal chondrocytes arranged in lobules, with variable atypia and occasional bi nucleation |

| 9 | Isbell et al./2017 | 27/M | Recurrence of progressively increasing left ankle pain and swelling along with tingling and burning in plantar aspect of foot | Radiograph - Opacity over the pre-Achilles fat pad and posterior ankle soft tissue; US - Joint capsule distension with intra articular debris and synovial hyperemia; MRI - Multiple large lobulated heterogeneous lesions with enhancement around FHL tendon extending into anterior tibiotalar joint and minimal involvement of sinus tarsi | Arthroscopic debridement of joint along with open excision | Cartilage hyaline nodules with minimal atypia of the chondrocytes and infrequent mitosis |

| 10 | Dheer et al./2020 | 49/F | Palpable swelling in the lateral aspect of ankle | US - Lobulated heterogeneous lesion with internal echogenicity; Doppler - neo vascularity; MRI - well lobulated mass near the peroneal tendon sheath with nodular and lace-like internal enhancement | Open surgical excision | Lobules of cartilage proliferation, minimal cellularity, no nuclear atypia and low nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio |

Abbreviations: B/K – below knee, CT – computerized tomography, MRI – Magnetic resonance imaging, FHL – Flexor Hallucis Longus, EDL – Extensor Digitorum Longus, FDL – Flexor Digitorum Longus, PT – Tibialis Posterior US- Ultrasonogram, M – Male, F – Female.

SC progresses in three phases according to Milgram, early phase which involves active synovitis without loose body formation, transitional phase wherein nodular synovitis is accompanied by presence of loose bodies and third phase with only presence of loose bodies [3]. Most authors have mentioned that the aetiology is unknown [3] and have discussed about spontaneous synovial chondrocyte metablastic transformation but trauma has been implicated as a reason for this transformation [12]. The disease predominantly remains monoarticular [[1], [2], [3],10] involving the larger synovial joints (IA type), namely the knee (50%) [1,3], hip, shoulder and elbows but has been reported to rarely occur in smaller joints such as the foot and ankle [1,[5], [6], [7], [8], [9]]; the term tenosynovial chondromatosis which is the equivalent of IA OC is used when the less commonly affected tissues such as bursa and tendon sheath synovium are affected (EA type) [5]. Many other names have been proposed in literature, such as tenosynovial osteochondromatosis, extrasynovial chondromatosis, soft tissue chondroma and synovial chondrometaplasia [1]. It is both continuous in process as well as having a significant local recurrence rate [1], thereby making the diagnosis imperative. The disease process involves a metaplastic conversion of synovial tissue into chondrocyte containing multi-nodular lumps which may calcify and ossify in around 90% of the cases [8], later detaching itself from the primary tissue and becoming free-floating loose bodies, which when intra-articular causes significant damage to the native cartilage, predisposing to secondary osteoarthritis [5], as well as more grievous conditions such as hip subluxation and pathological fracture have been reported. The disease process has neither been linked to any genetic variation [1] nor to a specific aetiology. The presentation is that of a slow growing, long standing mass, with or without pain (more frequent) and restricted joint mobility in mid-age individuals [8], males being affected almost twice as their counterparts [3], although having said that, their occurrence as early as seven years of age has been reported [8].

The histopathology is primarily that of bundling of chondrocytes with fluctuating degrees of varied nuclei and relatively less cellular stromal backdrop [3,4]. Another distinct feature is the stationing of numerous chondrocyte islands within the synovium. Also, a peripheral Giant cell reaction has been reported, the pivotal differentiating feature of TSC from Soft tissue chondroma is the presence of a multinodular appearance [5]. Additionally presence of ossification which is central along with rimming of osteoblast has been documented as a feature of SC [9]. The features such as presence of bony intrusion, proof of increased activity of chondrocytes amid few larger sized nuclei and its arrangement as sheets [10], enhanced solid matrix, presence of necrosis, increased cellularity and spindle shaped peripheral nuclei favours chondrosarcoma [3,6]. In our case, the classical histopathological findings were observed without any of the above mentioned features of malignant change.

The radiological diagnosis can be made depending upon the stage of the disease and this includes Plain radiographs, Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. In the early stages on x-rays, only a soft tissue swelling may be noticed since the ossification or calcification of cartilage has not occurred [7,9], which is what was noticed in our patient. Later, loose bodies within the joint or fine marked calcific bodies [4,6], eliciting a ring and arc pattern [8] around the juxta-articular areas may appear [9]. Also reported are findings such as damage to the cortex with irregular margins, however these findings are not confirmatory of malignant transformation [2,10], but invasion of medullary canal likely shifts the diagnosis towards a malignancy [10]. Other differential diagnosis to be considered in plain radiographs showing ossification along with loose bodies are Giant cell tumour (GCT), Synovial sarcoma and Chondrosarcoma [4]. In case of absence of ossification and loose bodies tenosynovitis, GCT of tenosynovium and TSC should be considered [4]. CT scan will not only help to reveal loose bodies which are calcified consequent to primary SC, but also differentiate them from focal wobbly loose bodies due to degenerative osteoarthritis. MRI reveals distension of fluid within the involved tendon sheaths, along with the presence of numerous loose bodies of similar size [8] and also throws light on the exact site of involvement [4]. In addition MRI helps to ascertain the damage to the surrounding ligaments and articular cartilage, which may aid in the decision making regarding the magnitude of surgery required [3]. MRI pictures revealing fluid distension of tendon sheaths and loose bodies should raise the suspicion of SC, Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) and rheumatoid arthritis (mainly presence of rice bodies) [4,8]. Additionally SC can be erroneously misinterpreted for pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS) considering that they are seen as signal voids but in PVNS the synovial lining will reveal as low signal on MRI due to presence of hemosiderin [3]. The use of intravenous contrast such as gadolinium is helpful in differentiating inflammatory changes as noticed in an infective process or JIA [4,3]. In our case the MRI findings were not classical but it has been reported to be varied [3].

The final diagnosis could be made exclusively by histopathology [1]. Open surgical excision [3,4] with removal of synovium, if there is an ongoing active inflammation of the synovium [5] and loose bodies [5,7,9] is the preferred treatment of choice for this condition. Neither chemotherapy nor radiotherapy play a part in the pre or post-surgical treatment protocol [3]. Recurrence rate reported in literature is slightly higher for the extra articular variant [1,4,8], which usually occurs within 5 years of initial resection. There is an occasional chance of malignant transformation, primarily in a long standing disease process, to chondrosarcoma which along with higher local recurrence rate warrants vigilant follow up [3,7,8].

4. Conclusion

EA SC is a rare differential for juxta-articular swelling around ankle joint. Clinical and radiological evaluation may contribute to the diagnosis but due to its varied presentation, confirmation can be made only with histopathology. MRI plays a key role in deciding the magnitude of the surgery. Surgical excision with debridement of the synovial tissue is the preferred treatment modality. Long term follow up is mandatory considering the higher documented risk of local recurrence and rare but reported malignant transformation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Nil.

Funding

Nil.

Ethical approval

Exempted by institutional ethical committee.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-chief of this journal on request.

Author’s contribution

Dr Mukhesh Thangavel - study concept, data collection, data analysis & writing the paper.

Dr Raghavan Sivaram - data analysis & writing the paper.

Dr Waqar Jan - Others.

Dr Ahmed Tariq - data collection and others.

Dr Saseendar Shanmugasundaram - data analysis and revision.

Registration of research studies

-

1.

Name of the registry: Not applicable.

-

2.

Unique identifying number or registration ID: Not applicable.

-

3.

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): Not applicable.

Guarantor

Dr Mukhesh Thangavel and Dr Waqar Jan.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Footnotes

Work performed at Department of Orthopaedics, King Hamad University Hospital, Bahrain.

References

- 1.Van P., Wilusz P.M., Ungar D.S., Pupp G.R. Synovial chondromatosis of the subtalar joint and tenosynovial chondromatosis of the posterior ankle. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2006;96(1):59–62. doi: 10.7547/0960059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sim F.H., Dahlin D.C., Ivins J.C. Extra-articular synovial chondromatosis. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1977;59(4):492–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dheer S., Sullivan P.E., Schick F. Extra-articular synovial chondromatosis of the ankle: unusual case with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiol. Case Rep. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2020.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pinter Z., Shah A., Netto C.C., Smith W., O’Daly A., Godoy-Santos A.L. Extensive synovial chondromatosis involving all flexor tendons in the tarsal tunnel: a case report. Rev. Bras. Ortop. (Sao Paulo) 2019;54(1):78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.rboe.2017.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lui T.H. Tenosynovial (extra-articular) chondromatosis of the extensor digitorum longus tendon and synovial chondromatosis of the ankle: treated by extensor digitorum longus tendoscopy and ankle arthroscopy. Foot Ankle Spec. 2015;8(5):422–425. doi: 10.1177/1938640014560165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tibrewal S.B., Iossifidis A. Extra-articular synovial chondromatosis of the ankle. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1995;77(4):659–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isbell J.A., Morris A.C., Araoye I., Naranje S., Shah A.B. Recurrent extra- and intra-articular synovial chondromatosis of the ankle with tarsal tunnel syndrome: a rare case report. J. Orthop. Case Rep. 2017;7(2):62–65. doi: 10.13107/jocr.2250-0685.752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winters N.I., Thomson A.B., Flores R.R., Jordanov M.I. Tenosynovial chondromatosis of the flexor hallucis longus in a 17-year-old girl. Pediatr. Radiol. 2015;45(12):1874–1877. doi: 10.1007/s00247-015-3383-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim S.R., Shin S.J., Seo K.B., Teong C.T., Hyun C.L. Giant extra-articular synovial osteochondromatosis of the sinus tarsi: a case report. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2013;52(2):227–230. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaiser T.E., Ivins J.C., Unni K.K. Malignant transformation of extra-articular synovial chondromatosis: report of a case. Skeletal Radiol. 1980;5(4):223–226. doi: 10.1007/BF00580594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agha R.A., Borrelli M.R., Farwana R., Koshy K., Fowler A., Orgill D.P., For the SCARE Group The SCARE 2018 statement: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2018;60:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cromar C.H. Synovial osteochondromatosis of the ankle secondary to acute injury to bone. J. Foot Surg. 1984;23(6):461–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomsen T.W., Hogrefe C.P., Hall M.M., Amendola A. Tenosynovial osteochondromatosis of the flexor hallucis longus in a division I tennis player. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2015;25(6):e74–e76. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]