Highlights

-

•

Head and neck tumors are subject to a strong dose response behaviour.

-

•

Short-term intra-arterial chemotherapy usually leads to rapid local response.

-

•

Local and systemic toxicity usually are absent or mild.

-

•

Quality of life is maintained.

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; HPV, human papilloma virus; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; ITP-F, isolated thoracic perfusion with chemofiltration

Keywords: Oropharyngeal carcinoma, Head neck tumors, Quality of life, Regional chemotherapy, Intra-Arterial infusion, Isolated perfusion, Implantable port catheter

Abstract

Introduction

This is a report about the first case of an advanced stage IV tonsil carcinoma treated with isolated thoracic perfusion and chemofiltration.

Presentation of case

The tumor extended beyond the midline with bilateral lymphnode metastases. Playing on wind instruments was impossible. As a professional Jazz saxophonist he refused mutilating surgery and chemoradiotherapy. After one isolated thoracic perfusion there was substantial tumor shrinkage. After three additional cycles of carotid artery infusion with chemofiltration a complete remission has been noted without systemic or local toxicity since 9 ½ years.

Discussion

Knowing the often considerable long-term damage after surgery and chemoradiotherapy of head and neck tumors, some patient reject conventional therapy. Because of the steep dose response curve in cancer chemotherapy, an increased drug exposure in terms of intra-arterial short-term infusions or isolated perfusion can induce rapid remission induction without significantly affecting the quality of life. Further studies comparing regional chemotherapies with conventional chemoradiotherapy are warranted.

Conclusion

Intra-arterially applied short-term chemotherapy may generate rapid and onlasting remissions at low side-effects.

1. Introduction

Worldwide, each year approximately 400.000 people come down with squamous epithelium cancers of the oropharynx. In this process one of the main causes of the increase is the human papilloma virus. Normally oropharyngeal carcinomas are treated with radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy. A heavy burden for these patients are the acutely or later occurring side-effects of the chemoradiotherapy which makes it most of the times necessary to insert a feeding-tube or tracheostoma and thus mean a strong impairment of the quality of life. After successful treatment of head and neck tumors the side-effect-related suicide rate is higher than in all other types of tumors [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5]]. On the contrary intra-arterial chemotherapy as a highly concentrated isolated thoracic perfusion combined with carotid artery infusion and chemofiltration is a gentle and low side-effect therapy option with good long-term results [6,7]. Here we discuss the clinical course of a patient with advanced oropharyngeal carcinoma treated with regional chemotherapy only. This current case has been reported in line with the Surgical Case Report (SCARE) criteria [8].

2. Presentation of case

In October 2010 an advanced metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the left tonsil with bilateral lymphnode metastases and a prominent metastasis of 3.5 cm in diameter on the right side of the neck was diagnosed in a 60-year-old patient. The tumor was extending beyond the midline, invading the soft palate, and the CT-scan from December 2010 showed large, sometimes centrally necrotic masses on both sides of the tumor, as well as clinically a marked clumping and hardening of the soft palate. The HPV-status was not known. The patient was advised externally to have the tumor and the soft palate removed surgically along with neck dissection on both sides, tracheostomy, feeding-tube, and subsequent radiotherapy. He consistently rejected this since otherwise he would have been unable to continue his career as a Jazz saxophonist. When he first presented to the clinic, his voice was hoarse and barely audible, and playing wind instruments was impossible due to the hardened palate. His mood was very depressed. He was informed about regional chemotherapy in terms of isolated thoracic perfusion as a last remaining therapeutic option and signed the informed consent.

In the first isolated thoracic perfusion (Fig. 1) on 7th December 2010 the chemotherapeutic agents were administered via two angiographically placed common carotid artery catheters (Fig. 2) at a dosage of totally 100 mg cisplatin, 60 mg adriamycin and 20 mg mitomycin followed by chemofiltration in order to reduce systemic toxicity. After a 15 min short-term carotid artery infusion of this three-drug combination into the isolated perfusion circuit, followed by 45 min of chemofiltration, the patient did not suffer any systemic toxicity and reported 14 days thereafter a substantial improvement of his voice and disappearance of the previously palpable lymphnode metastasis on the right side of the neck.

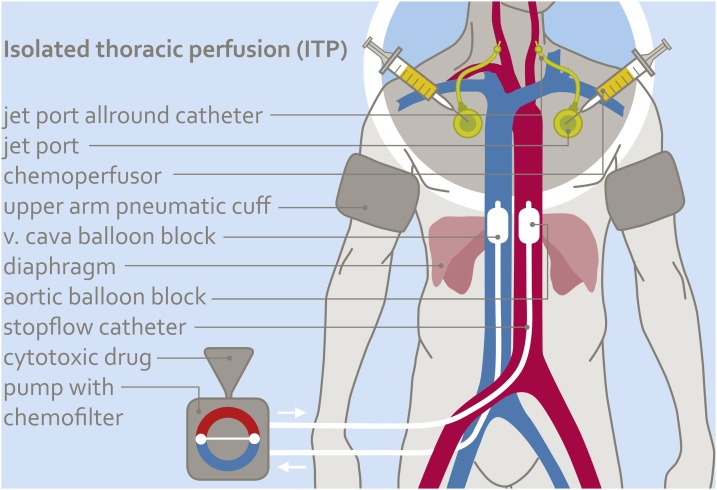

Fig. 1.

Scheme of isolated thoracic perfusion. Aorta and vena cava are balloon blocked at the level of the diaphragm. Both upper arms are blocked with pneumatic cuffs. Chemotherapy is administered over 15 min via implanted or angiographic carotid artery catheters. After 15 min all blocks are released and chemofiltration for elimination of residual drugs is started.

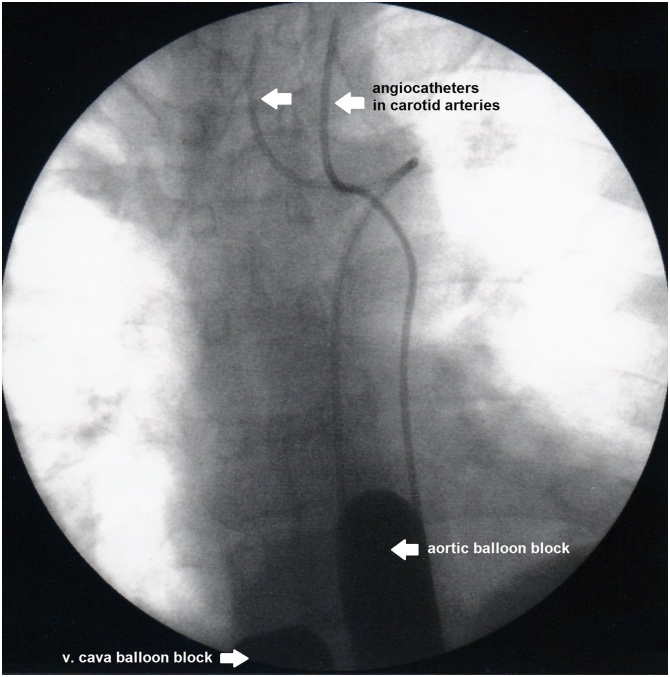

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative contrast imaging of two angiographic carotid artery catheters and balloon blocked aorta and vena cava.

During the second in-patient stay from 2nd January 2011, a common carotid artery port catheter was implanted on both sides (Fig. 4). The intra-arterial catheter, to be implanted into the carotid arteria should not exceed 1.05 mm outside-diameter and its inner diameter should not be below 0.45.

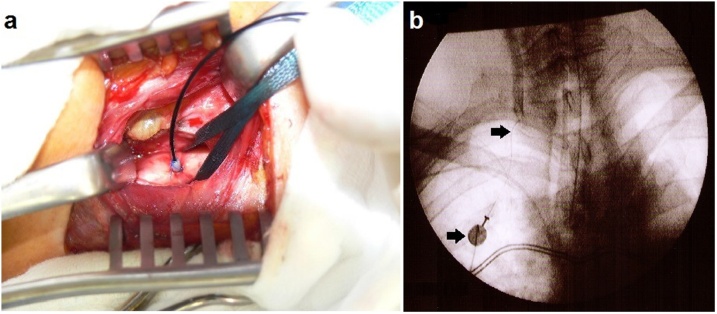

Fig. 4.

a, b a) End-to-side implantation of the intra-arterial Jet-Port Allround catheter, b) Contrast imaging of carotid artery through implanted Jet-Port catheter.

On 18th January 2011, a second course of intra-arterial short-term infusion via both carotid artery port catheters was administered during ten minutes along with simultaneous chemofiltration via a Sheldon-catheter in the internal jugular vein. The previously submandibular lymphnode mass was no longer palpable before the second therapy cycle and the patient reported that he could now play the saxophone without any problems which was impossible before therapy because of the hard infiltration of the soft palate. Subsequently, two more cycles were carried out on the 15th February 2011 and 25th March 2011 via implanted carotid artery port catheters with simultaneous chemofiltration.

A control CT-scan from 5th January 2011 showed compared to the previous examination from 2nd December 2010 a substantial downsizing of the primary tumor and the previously enlarged lymphnodes in the left upper jugular group. The tumor was no longer detectable in the July 2011 CT-scan (Fig. 3a, b, c).

Fig. 3.

a, b, c a) CT-scan before, b) CT-scan four weeks after, c) CT-scan seven months after isolated thoracic perfusion.

The patient not only experienced an improvement in his quality of life under the intra-arterial chemotherapy, he was also able to resume his job as a professional Jazz saxophonist. Neither a tracheostomy nor a feeding-tube was necessary. Meanwhile the patient has been free of recurrence and symptoms for 9 years and 5 months. All check-ups since the end of therapy such as CT, panendoscopy with biopsies and MRI’s remained without evidence of a relapse. A sustained complete remission of the primary tumor and all lymphnode metastases with unimpaired quality of life was achieved with an initial isolated perfusion followed by three courses of intra-arterial short-term infusions without locally invasive measures.

3. Discussion

Radiochemotherapy as the standard treatment for head and neck cancers achieves a high rate of sustained complete remissions. These good clinical results, however, are clouded in part by local and systemic toxicity and side-effects. After successful treatment of head and neck tumors, the side-effect-related suicide rate is the highest of all treated tumor entities [[2], [3], [4], [5]]. Proton-therapy and intensity-modulated radiotherapy [9], especially in patients with better prognosis, try to reduce the long-term side-effects such as disorders of the swallowing and language function and xerostomia with pain. This brings some reduction in local toxicity [1]. Under intra-arterial chemotherapy, however, swallowing and speech disorders, dry mouth and pain never occurred. No patient needed a feeding-tube or tracheostomy. Quality of life was definitely better. The survival times in advanced tumors are at least comparable. Every day of quality of life gained is important for those severely affected patients. It should be noted here that remissions, if the tumor responds, usually occur quickly, within two to three weeks. This was also seen in this patient who had an impressive immediate response right after the first therapy with isolated thoracic perfusion. The advantage obviously lies in the application as a short-term infusion over a few minutes into the isolated circuit which allows a sufficient and extremely effective exposure to cytostatic agents (concentration x time) with comparatively low and systemically less toxic doses [6,7]. The chemofiltration performed directly after the isolated perfusion reduces both, immediate and cumulative toxicity. With regard to immediate toxicity at these relatively low total doses of drugs, chemofiltration is not absolutely necessary or mandatory, but in case of a prospectively required larger number of therapies, it postpones the cumulative toxicity of drugs. Thus, it plays an important role in maintaining quality of life.

The idea to administer chemotherapeutics through the intra-arterial route is not new [[10], [11], [12]], but never made a breakthrough, mostly because the procedure is technically more complex than a normal intra-venous infusion of drugs. Long-term infusions of chemotherapeutic agents through angiographic catheters require special care and monitoring. The only randomized study intra-arterial versus intra-venous chemotherapy for head and neck cancer did not show a significant advantage of either therapy in terms of clinical results, but systemic chemotherapy was easier to handle. Both treatment arms were combined with radiotherapy [13].

In our patient collective [6,7] there are predominantly very advanced cases treated with intra-arterial chemotherapy only, none of which required a tracheostomy or feeding-tube. A randomized study conventional chemoradiotherapy versus intra-arterial chemotherapy is therefore in preparation.

Chemotherapy in terms of intra-arterial infusion alone or in combination with systemic chemotherapy [14,15] or combined with radiotherapy revealed good results [16] but was also associated with adverse events such as chemoradiotherapy with supradose of intra-arterial cisplatin [17]. The basic problem is how to perform the cytostatic exposure. Extremely high doses or concentrations given as a bolus infusion can cause substantial toxicity, low concentrations, however, over a long period of time may have too little effect on the tumor but cumulatively develop high systemic toxicity. Short-term infusions over 7–12 min or 15 min infusions at higher total doses in the isolated perfusion system have shown to generate maximal efficacy at low toxicity [6,7].

Due to impressive response after the first isolated perfusion subsequent therapies were performed in terms of more or less minimal invasive arterial-port-infusion and chemofiltration.

This is the first case of advanced head and neck cancer treated with chemotherapy in an isolated perfusion circuit. The method itself has been applied in lung cancer [18], pleural mesothelioma [19] and lung metastases from breast cancer [20].

Intra-arterial chemotherapy with or without isolated perfusion techniques consistently also gave good results for head and neck tumors, but one limitation of these studies is that there is currently no direct comparison of chemoradiotherapy with intra-arterial chemotherapy in a prospective randomized study which shows the proportionality between survival time and quality of life.

4. Conclusion

Intra-arterially applied short-term chemotherapy may generate rapid and onlasting remissions at low side-effects.

Sources of funding

This report receive no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

Ethic approvals was not required and patient-identifying knowledge was not presented in the report.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Karl R. Aigner: Conceptualization, Writing, Review, Editing, Supervision – Original draft. Performed surgery/intervention.

Emir Selak: Review. Performed Surgery/intervention.

Kornelia Aigner: Review, Data Collection, Data Analysis, Supervision.

Registration of research studies

-

1.

Name of the registry: Not applicable as no human research study.

-

2.

Unique identifying number or registration ID: Not applicable as no human research study.

-

3.

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): N/A.

Guarantor

All mentioned authors were involved in the preparation of this case report and accept full responsibility for the work, had access to the data and controlled the decision to publish.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgments

Giuseppe Zavattieri: Provided writing assistance, editing.

Contributor Information

Karl R. Aigner, Email: info@prof-aigner.de.

Emir Selak, Email: e.selak@medias-klinikum.de.

Kornelia Aigner, Email: kornelia.ainger@medias-klinikum.de.

References

- 1.Ringash J. Survivorship and quality of life in head and neck cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015;33:3322–3327. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.4115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osazuwa-Peters N., Boakye E.A., Walker R.J., Varvares M.A. Suicide: a major threat to head and neck cancer survivorship. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34:1151. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.4673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Misono S., Weiss N.S., Fann J.R., Redman M., Yueh B. Incidence of suicide in persons with cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:4731–4738. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.8941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anguiano L., Mayer D.K., Piven M.L., Rosenstein D. A literature review of suicide in cancer patients. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35:E14–E26. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31822fc76c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Briscoe J., Webb J.A. Scratching the surface of suicide in head and neck cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016;142:610. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2016.0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aigner K.R., Gailhofer S., Aigner K.R. Carotid artery infusion via implantable catheters for squamous cell carcinoma of the tonsils. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2018;16:104. doi: 10.1186/s12957-018-1404-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aigner K.R., Selak E., Aigner K.R. Short-term intra-arterial infusion chemotherapy for head and neck cancer patients maintaining quality of life. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2018;145:261–268. doi: 10.1007/s00432-018-2784-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agha R.A., Borrelli M.R., Farwana R., Koshy K., Fowler A., Orgiall D.P., For the SCARE Group The SCARE 2018 statement: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2018;60:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kam M.K., Leung S.F., Zee B. Prospective randomized study of intensity-modulated radotherapy on salivary gland function in early-stage nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25:4873–4879. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stephens F.O. Why use regional chemotherapy? Principles and pharmacokinetics. Reg. Cancer Treat. 1988;1:4–10. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howell S.B. Editorial: improving the therapeutic index of intra-arterial cisplatin chemotherapy. Eur. J. Cancer Clin. Oncol. 1989;25:775–776. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(89)90119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stephens F.O. Intra-arterial chemotherapy in head and neck cancer. Historical perspectives – important developments, contributors and contributions. In: Eckardt A., editor. Intra-Arterial Chemotherapy in Head and Neck Cancer – Current Results and Future Perspectives. Einhorn-Presse Verlag; Reinbek: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rasch C.R., Hauptmann M., Schornagel J. Intra-arterial versus intravenous chemoradiation for advanced head and neck cancer: results of a randomized phase 3 trial. Cancer. 2010;116:2159–2165. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee Y.Y., Dimery I.W., Van Tassel P. Superselective intra-arterial chemotherapy of advanced paranasal sinus tumors. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1989;115:503–511. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1989.01860280101026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forastiere A.A., Baker S.R., Wheeler R. Intra-arterial cisplatin and FUDR in advanced malignancies confined to the head and neck. J. Clin. Oncol. 1987;5:1601–1606. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1987.5.10.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kovacs A.F. Response to intraarterial induction chemotherapy: a prognostic parameter in oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2006;28:678–688. doi: 10.1002/hed.20388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robbins K.T., Kumar P., Harris J. Supradose intra-arterial cisplatin and concurrent radiation therapy for the treatment of stage IV head and neck squamous cell carcinoma is feasible and efficacious in a multi-institutional setting: results of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Trial 9615. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23(7):1447–1454. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aigner K.R., Selak E. Isolated thoracic perfusion with carotid artery infusion for advanced and chemoresistant tumors of the parotid gland. In: Aigner K.R., Stephens F.O., editors. Induction Chemotherapy. Springer International Publishing; 2011. pp. 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aigner K.R., Selak E., Gailhofer S. Isolated thoracic perfusion with chemofiltration for progressive malignant pleural mesothelioma. OncoTargets Ther. 2017;10:3049–3057. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S134126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guadagni S., Aigner K.R., Zoras O. Isolated thoracic perfusion in lung metastases from breast cancer: a retrospective observational study. Updates Surg. 2019;71:165–177. doi: 10.1007/s13304-018-00613-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]