Abstract

Patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) can develop strong drug resistance following long-term treatment with platinum-based drugs. Increasing doses of chemotherapeutic drugs fail to obtain better results, and serious complications occur. It has been demonstrated that upregulation of excision repair cross-complementary 1 (ERCC1) in lung cancer cells is closely associated with cell resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy. In addition, curcumin (CMN) enhances antitumor effects in NSCLC by downregulating ERCC1. The aim of the present study was to investigate the effects of demethoxycurcumin (DMC), a curcuminoid, on the reversal of resistance of NSCLC cells in vitro and in vivo. The present study demonstrated that DMC significantly increased the sensitivity of DDP in DDP-resistant A549 (A549/DDP) cells. The results from an MTT assay demonstrated that DMC combined with DDP significantly attenuated the proliferation of A549/DDP cells. Furthermore, DMC exhibited decreased toxicity in normal lung fibroblast MRC-5 cells. In addition, following treatment of A549/DDP cells with a combination of DMC and DDP, the expression of ERCC1 was reduced, the protein levels of Bcl-2 and Bax were decreased and increased, respectively, whereas caspase-3 was activated, according to results from western blotting. Finally, DDP combined with DMC significantly attenuated A549/DDP cell-derived tumor growth in vivo. Taken together, the findings from the present study suggested that DMC in combination with DDP may be considered as a novel combination regimen for restoring DDP sensitivity in DDP-resistant NSCLC cells.

Keywords: demethoxycurcumin, cisplatin, excision repair cross-complementary 1, drug combination, drug resistance

Introduction

Lung cancer is a highly metastatic type of cancer with an increasing incidence rate worldwide every year with an estimated 1.6 million mortalities in 2012 (1). The main subtypes of lung cancer are small cell lung cancer (SCLC) (10–15%) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (80–85%), with the latter being the most common type (2). Further investigation on the treatment of NSCLC is therefore urgently needed. Platinum-based drugs, including cis-dichlorodiamino platinum [cisplatin (DDP)], carboplatin and lobaplatin, are currently the most potent chemotherapeutic agents used to treat NSCLC (3). However, prolonged use of DDP may lead to drug resistance, thus resulting in reduced clinical curative effects, which in turn may lead to lung cancer recurrence and distant metastasis (4). Previous studies have demonstrated that the main mechanisms underlying DDP resistance in cancer cells include increased cellular DDP detoxification activity, inhibition of apoptosis and an enhanced DNA damage repair capacity (5,6). Investigating the enhancement of DDP sensitivity in DDP-resistant cancer cells may therefore be of great importance.

Curcuminoids, which are yellow pigments extracted from turmeric rhizomes, are used to treat a wide variety of diseases, including neurodegenerative diseases, cardiovascular diseases, metabolic disorders and lung fibrosis (7–10). Furthermore, these compounds have been demonstrated to exhibit potent anticancer activities at initial, promotion and progression stages of tumor development in numerous cancers, including colon, cervical, ovarian and gastric cancers (11). Curcuminoids consist of three main bioactive components, curcumin (CMN), demethoxycurcumin (DMC) and bisdemethoxycurcumin (BDMC) (12). CMN is the most widely studied compound of the curcuminoids and is used in the treatment of several solid tumors and hematological malignancies, such as cancers of the digestive, lymphatic and immune, pulmonary and the skin, due to its great antitumor potential (13–15). However, several studies have demonstrated that CMN exhibits poor oral bioavailability (16–18). Quitschke (17) reported that DMC is more stable in the blood compared with CMN. Chemically, DMC is very similar to CMN. DMC only lacks the methoxy group that is linked to the benzene ring. This minor difference in chemical structure provides DMC with increased chemical stability and activity (19,20). It has also been reported that DMC modulates inhibition of cell survival, tumor suppression, and activates mitochondrial and death receptor pathways (21–24). The therapeutic potential of DMC in the adjuvant treatment of various diseases should therefore be further investigated.

The present study aimed to investigate whether DMC in combination with DDP could increase DDP sensitivity in DDP-resistant A549 cells (A549/DDP), similar to taxanes, pemetrexed and gemcitabine. The present study may provide a novel candidate drug for combined chemotherapy following clinical lung cancer surgery.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human alveolar basal epithelial adenocarcinoma cells (A549 cells) and human lung fibroblasts (MRC-5 cells) were purchased from The Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (cat. nos. SCSP-503 and SCSP-5040, respectively). A549 cells were cultured in Ham's F-12K (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) medium (cat. no. 21127-022; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). MRC-5 cells were cultured in MEM (cat. no. 11090081; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 1X GlutaMAX (cat. no. 35050061; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 1X non-essential amino acids (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; cat. no. 11140050) and 1 mM sodium pyruvate solution (cat. no. 11360070; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). A549/DDP cells were obtained from Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (cat. no. CM-0519) and were cultured in Ham's F-12K supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 µg/ml DDP and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The medium was changed every two days and cells were passaged when the cell density reached 80–90%.

MTT assay

All cells were seeded into 96-well plates at the density of 5×103 cells/well (A549 and A549/DDP cells) or 1×104 cells/well (MRC-5 cells). A549 cells were treated with DDP at various concentrations (1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, 20 and 40 µM). A549/DDP cells were treated with higher concentrations of DDP (5, 10, 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100 µM). A549, A549/DDP and MRC-5 cells were treated with DMC at doses of 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 and 35 µM. After culturing the cells for a specified period of time (24, 48, 72 or 96 h), 20 µl MTT (5 µg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) was added and the cells were cultured in the incubator for 1 h. Next, the culture medium was discarded carefully, 100 µl DMSO was added and the plate was agitated for 10 min on a shaker. The absorbance was read at 550 nm on a microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc.).

TUNEL assay

Coverslips were inserted into a 24-well plate and then A549/DDP cells were seeded on the coverslips at the density of 5×104 cells per well. After 24 h, the medium was replaced with medium containing drugs (10 µM DDP, 5 µM DMC or both), and after 48 h incubation, TUNEL staining was performed. Briefly, cells were washed gently with PBS to remove non-adherent cells and were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were then incubated with PBS containing 0.1% Triton at 4°C for 10 min for permeabilization. The solution was discarded and 50 µl of TUNEL detection solution (cat. no. C1090; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) (2 µl of TdT enzyme with 48 µl of fluorescent labeling solution) was added at 37°C for 60 min in the dark. Finally, slides were mounted with an anti-fluorescence quencher (cat. no. G1401; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) and were kept at 4°C. Slides were observed under a fluorescence microscope (magnification, ×200) within one week.

Western blotting

A549 cells were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer (cat. no. P0013B; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) after 48 h of drug treatment. Total proteins were extracted and were denatured at 95°C for 10 min. The protein concentration was determined by the BCA method, and protein concentration was subsequently normalized using loading buffer. Proteins (30 µg) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and were then transferred onto PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% skimmed milk in PBST for 2 h at room temperature and were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Next, membranes were washed three times with PBS for 15 min and were incubated with secondary antibodies at room temperature for 2 h. Membranes were washed three times with PBS for 15 min and were exposed to 200 µl enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Bands were detected on a Bio-Rad instrument and relative expression levels were normalized to endogenous control using Image-Pro Plus software v.6.0 (National Institutes of Health). The primary antibody against ERCC1 was obtained from Abcam (1:2,000; cat. no. ab129267). The antibodies against Bcl-2 (cat. no. 4223), Bax (cat. no. 5023), caspase 3 (cat. no. 9662), PARP (cat. no. 9532), cleaved caspase 3 (cat. no. 9664), cleaved PARP (cat. no. 5625) and β-actin (cat. no. 4970) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. and were used at a dilution of 1:1,000. The secondary goat anti-rabbit antibodies (cat. nos. 7074 and 7076; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) were used at a dilution of 1:5,000.

Subcutaneous xenograft assay

A total of 16 male BALB/c nude mice (4–5 weeks, 20–24 g) were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co. The mice were housed under specific pathogen free (SPF) conditions and fed with SPF standards of care, The mice were housed with a 12 h light/dark cycle at 25±2°C and 50±10% humidity, and were provided with sterile food and water. A549/DDP (5×105) cells were subcutaneously injected into the left axilla of 16 nude mice. When the maximum tumor volume reached 100 mm3, 16 mice were randomly divided into four groups of four mice as follows: Control group, monotherapy groups (DDP or DMC) and a combination treatment group. DDP was injected intraperitoneally at a dose of 6.0 mg/kg every three days and DMC was injected intraperitoneally at a dose of 30 mg/kg every day for 20 days. DDP and DMC were dissolved in DMSO (50 µl in DMSO per mouse for injection). The control group was treated with DMSO (50 µl per mouse). The tumor volume was measured every 4 days until day 20 using the following formula: Tumor volume (units, mm3)=width2 × length/2. The mice were sacrificed on day 20. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 300 mg/kg ketamine and 20 mg/kg xylazine for euthanasia, and the death of mice was confirmed when the mice stopped breathing.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Mouse subcutaneous tumors were collected following euthanasia. Subsequently, tissue sections (4-µm) were dewaxed with xylene (twice) for 10 min and hydrated using a descending alcohol series (100% twice, 90% twice, 75% twice) for 3 min at room temperature. Antigens were retrieved in a 95°C water bath for 20 min. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using 3% hydrogen peroxide for 20 min at room temperature. After blocking with 5% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), the sections were incubated with primary antibody (Ki-67, 1:200; cat. no. 9027S; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) at 4°C overnight. The next day, sections were incubated with secondary antibody (1:200; cat. no. ZDR-5306; OriGene Technologies Inc.) for 2 h at 37°C, followed treating with DAB chromogen (1 drop of the DAB Chromogen per ml of substrate buffer; Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) and hematoxylin (cat. no. C0107; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 2 min at room temperature. Finally, the slides were dehydrated and fixed by resin and observed with an Olympus inverted microscope (Olympus Corporation; magnification, ×200).

Statistics analysis

Tumor size data were presented as mean ± SEM, all other data were represented mean ± SD. Student's unpaired t-test was used to analyze the statistical significance among two groups. One-way ANOVA followed by the post hoc Bonferroni's test was used to compare the differences among ≥3 groups. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS v.20.0 software (IBM Corp.). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

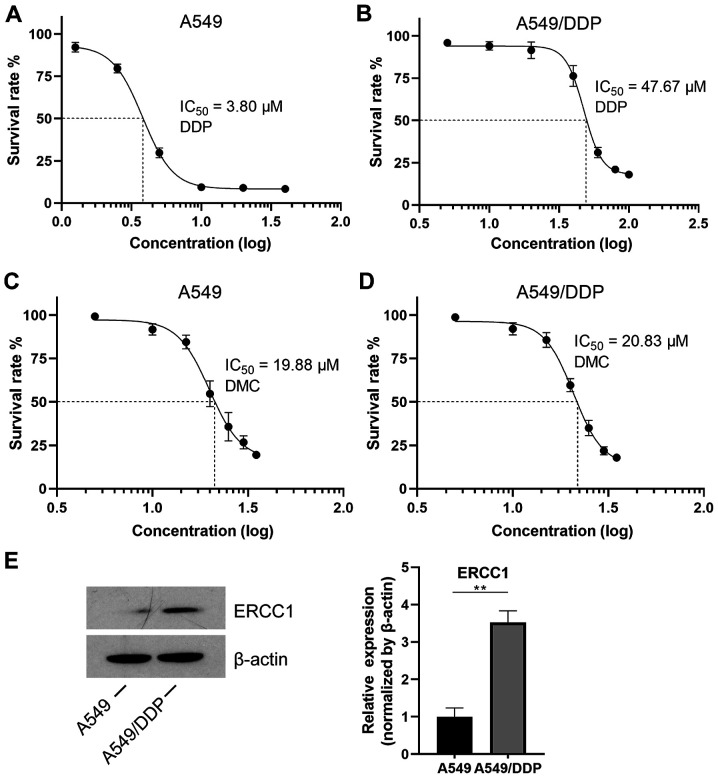

A549/DDP cells are resistant to DDP but not to DMC

A549 and A549/DDP cells were treated with different concentrations of DDP for 48 h. The results from the MTT assay demonstrated that the IC50 value of DDP in normal A549 cells was 3.8 µM, whereas it reached 47.67 µM in A549/DDP cells, which is more than 10 times higher compared with that in normal A549 cells (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, DDP had almost no effect on A549/DDP cells at concentrations ranging from 5–30 µM (Fig. 1B). This finding indicated that A549/DDP cells were successfully induced. In addition, A549 and A549/DDP cells were treated with different concentrations of DMC. The IC50 values of DMC in A549 and A549/DDP cells were 19.88 and 20.83 µM, respectively (Fig. 1C and D), indicating that induced A549/DDP cells were not resistant to DMC. It has been reported that targeting ERCC1 may mediate therapeutic sensitivity to platinum-based drugs (25). Subsequently, to further explore the resistance of A549/DDP cells to DDP, western blotting was performed. The results demonstrated that the expression of ERCC1 was significantly increased in A549/DDP cells compared with that in A549 cells (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1.

IC50 values in A549 and A549/DDP cells. (A) After 48 h, A549 cells were treated with DDP and an MTT assay was performed. The concentrations of DDP were 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, 20 and 40 µM. (B) A549/DDP cells were treated with increasing concentrations of DDP (5, 10, 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100 µM). (C) A549 and (D) A549/DDP cells were treated with DMC at the same doses. The drug doses were 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 and 35 µM. (E) Expression of ERCC1 in both A549 and A549/DDP cell lines. **P<0.01. DDP, cisplatin; DMC, demethoxycurcumin; ERCC1, excision repair cross-complementary 1.

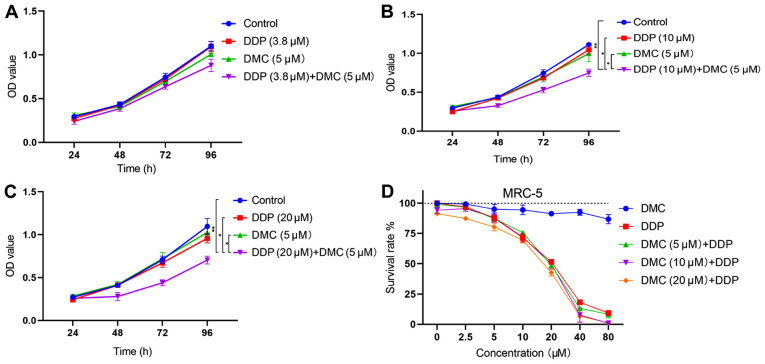

Combination treatment with DMC increases the sensitivity of A549/DDP cells to DDP

The efficiency of DMC and DDP combined treatment in A549/DDP cells was determined and showed that all DMC concentrations (5, 10 and 20 µM) could restore the cell sensitivity to DDP in drug-resistant A549/DDP cells (Table I). Based on the concentration screening results, the lowest DMC concentration (5 µM) was chosen for further experiments. A549/DDP cells were treated with DDP (3.8 µM) in combination with DMC. The DDP concentration of 3.8 µM corresponded to the IC50 value obtained in normal A549 cells. However, the combined drug group did not significantly inhibit cell proliferation compared with the single drug groups (Fig. 2A; combined drug group vs. DDP, P=0.112; combined drug group vs. DMC, P=0.053). Therefore, cells were subsequently treated with elevated concentrations of DDP. The results demonstrated that combination treatment with 10 and 20 µM DDP significantly inhibited the proliferation of A549/DDP cells (P<0.05; Fig. 2B and C). Subsequently, normal human lung fibroblasts (MRC-5 cells) were treated with high concentrations of DMC. The results from the MTT assay revealed that DMC exhibited low toxicity in MRC-5 cells, even at concentrations up to 80 µM (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, combination treatment with DMC and DDP did not induce significantly greater toxicity in MRC-5 cells compared with DDP monotherapy (Fig. 2D).

Table I.

Synergistic roles of DMC and DDP in A549/DDP cells.

| A, 5 µM DMC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell survival effects, % | ||||

| DDP, µM | DMC | DDP | DMC + DDP | CDIa |

| 3.8 | 94.71±0.49 | 99.40±0.14 | 80.94±2.01 | 0.86 |

| 10 | 94.71±0.49 | 95.52±0.09 | 62.77±0.14 | 0.69 |

| 20 | 94.71±0.49 | 90.14±0.05 | 53.40±0.23 | 0.63 |

| B, 10 µM DMC | ||||

| Cell survival effects, % | ||||

| DDP, µM | DMC | DDP | DMC + DDP | CDIa |

| 3.8 | 87.16±0.49 | 99.40±0.14 | 73.31±1.19 | 0.85 |

| 10 | 87.16±0.49 | 95.52±0.09 | 56.11±0.34 | 0.67 |

| 20 | 87.16±0.49 | 90.14±0.05 | 41.34±0.08 | 0.52 |

| C, 20 µM DMC | ||||

| Cell survival effects, % | ||||

| DDP, µM | DMC | DDP | DMC + DDP | CDIa |

| 3.8 | 59.6±0.11 | 99.40±0.14 | 53.32±1.19 | 0.94 |

| 10 | 59.6±0.11 | 95.52±0.09 | 36.19±0.34 | 0.64 |

| 20 | 59.6±0.11 | 90.14±0.05 | 27.33±0.08 | 0.50 |

CDI=AB/(A × B), with AB being the relative cell viability of the combination, and A or B being the relative cell viabilities of single-agent groups. CDI<1 indicates synergistic effects, CDI=1 indicates additive effects and CDI>1 indicates antagonistic effects. CDI, coefficient of drug interaction; DMC, demethoxycurcumin; DDP, cisplatin.

Figure 2.

Combined treatment with DMC increases DDP sensitivity in A549/DDP cells. (A) Treatment of A549/DDP cells with DDP (3.8 µM) and DMC (5 µM). (B and C) A549/DDP cells were treated with high concentrations of DDP (10 and 20 µM) and DMC (5 µM). (D) MRC-5 cells were treated with different concentrations of DMC for 48 h. MRC-5 cells were also treated with single DMC or DDP (0, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 40 and 80 µM) or the combination of DMC (5, 10 and 20 µM) and different concentrations of DDP (0, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 40 and 80 µM) for 48 h. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. DMC, demethoxycurcumin; DDP, cisplatin; OD, optical density.

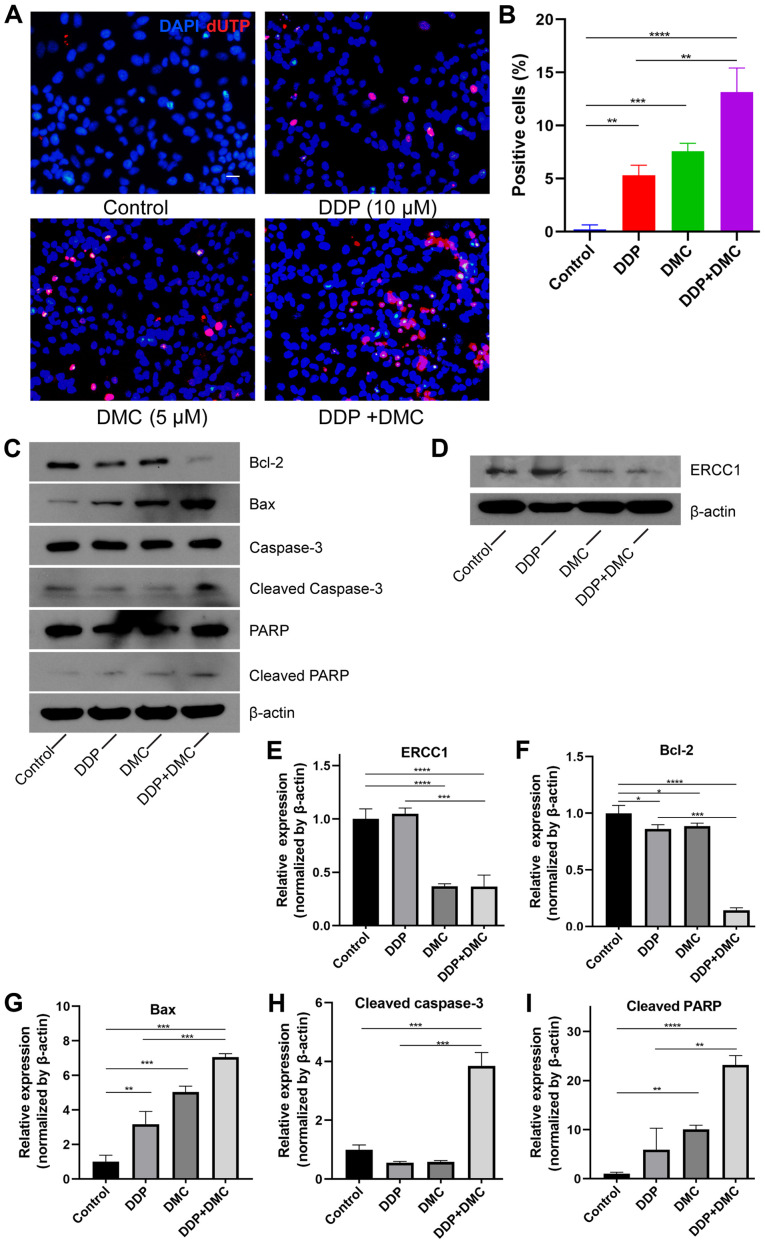

Combination drug treatment promotes A549/DDP cell apoptosis by activating the caspase-3 signaling pathway

The MTT assay demonstrated that the drug combination significantly attenuated the proliferation of the A549/DDP cells. Furthermore, following treatment with the drug combination for 48 h, the results from the TUNEL assay revealed that the apoptosis rate of the A549/DDP cells in the combined drug group was significantly elevated compared with control and monotherapy groups (DDP or DMC) (Fig. 3A). The apoptosis rates in the single drug groups were 5.30±0.95 and 7.57±0.76% in DDP and DMC groups, respectively, whereas it reached 13.13±2.29% in the combined drug group. In addition, DMC increased the sensitivity of A549 cells to DDP (P<0.01; Fig. 3B). To investigate the mechanism underlying A549/DDP cell apoptosis, the expression of apoptosis-related proteins was detected by western blotting. ERCC1 expression was significantly decreased in the DMC treatment group (Fig. 3D and E). Bax and Bcl-2 proteins belong to the Bcl-2 family of genes, whereas Bcl-2 is involved in the inhibition of apoptosis. By contrast, Bax not only antagonizes the inhibitory effect of Bcl-2 but also promotes apoptosis (26,27). CMN co-treatment enhanced the effects on apoptosis in A549/DDP cells. The results demonstrated that Bcl-2 and Bax expression was decreased and increased, respectively, in the combination groups (Fig. 3C and F-G). In addition, expression of cleaved caspase-3 was increased in the combination group compared with control and single drug groups (Fig. 3C and H). Poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP), a cleavage substrate of caspase, is a major contributor to apoptosis and cleaved PARP is considered an important indicator of apoptosis and an activator of caspase 3 cleavage (28). The results demonstrated that cleaved PARP expression was increased in the combined drug group, indicating that the caspase-mediated apoptosis pathway was activated (Fig. 3C-I).

Figure 3.

DDP in combination with curcumin promotes A549/DDP cell apoptosis. A549/DDP cells were treated with DDP (10 µM), DMC (5 µM) or both for 48 h. (A and B) TUNEL staining results showed that the apoptosis rate was significantly increased in the combined drug group (DDP group vs. DDP + DMC group; P<0.01). Scale bar, 20 µm. (C-I) Western blotting showed that the expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 was decreased and that of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax was increased in the combination group. DMC treatment downregulated ERCC1 expression in A549/DDP cells. Expression of cleaved caspase-3 and cleaved PARP were also increased. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. DDP, cisplatin; DMC, demethoxycurcumin; ERCC1, excision repair cross-complementary 1; PARP, poly ADP-ribose polymerase.

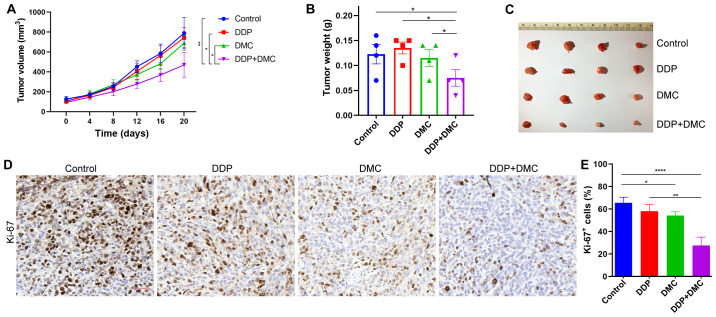

Combination drug treatment inhibits the proliferation of A549/DDP cells in vivo

The present study investigated whether the drug combination could exert the same effects on inhibiting proliferation in vivo. To do so, a subcutaneous ectopic tumor formation model was established by injecting A549/DDP cells into nude mice, which were then treated with DMSO (Control group), single drug (DDP or DMC) and a combination treatment. The results revealed that the tumor size in the combination group was significantly lower compared with that in the single drug groups (Fig. 4A). Following tumor growth in nude mice for 20 days, tumors were removed and weighed. Consistent with the tumor size measurements, tumor weight in the combination group was also lower than that in the other groups (Fig. 4B and C). In addition, immunohistochemical staining indicated that the Ki-67 proliferation index was significantly decreased in the combined drug group compared with that in the other groups (Fig. 4D and E). These findings confirmed the in vitro effects of DDP treatment combined with DMC.

Figure 4.

Combination treatment inhibits A549/DDP cell-derived subcutaneous ectopic tumor growth. (A) Tumor volume was measured from day 0 to day 20 in each group of mice. (B) Tumor weights of A549/DDP xenografts at day 20 following treatment. (C) A549/DDP cell-derived subcutaneous neoplasms on day 20. (D and E) Expression of Ki-67 was detected by immunohistochemistry. Scale bar in (D)=50 µm. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001. DDP, cisplatin.

Discussion

DDP is considered as a classic chemotherapeutic drug for patients with NSCLC; however, prolonged chemotherapy gradually increases the risk of resistance and side effects may occur, leading therefore to reduced treatment efficacy and sharp deteriorations in the health of patients (29,30). NSCLC treatment strategies involving the combination of DDP with other chemotherapy drugs, including taxanes, pemetrexed and gemcitabine, may significantly reduce drug resistance (31). There is increasing attention for the combined use of drugs as a way to reduce resistance to single drugs (32).

Although DMC and BDMC exhibit structural similarities to CMN, it is difficult to isolate both drugs from Curcuma longa, making their study also difficult (33). A previous study reported that CMN, DMC and BDMC were efficiently isolated from Curcuma longa with a purity >98% (34). Compared with CMN and BDMC, DMC has the most potent inhibitory effect on the migration and balloon injury-induced neointimal formation of vascular smooth muscle cells (35). Furthermore, DMC shows the greatest inhibitory effect among all curcuminoids, as demonstrated by rhodamine 123 efflux and calcineurin-AM accumulation assays (36). Numerous studies have revealed that curcuminoids could restore drug sensitivity in drug-resistant cancer cells (37,38). Furthermore, in colorectal cancer cell lines with acquired resistance to oxaliplatin (OXA), treatment with CMN in combination with OXA is more potent and results in reversion of OXA resistance (39). In addition, DMC in combination with DDP significantly improves post-target resistance to DDP in NSCLC cells (40). In the present study, the DDP-resistant NSCLC A549/DDP cell line was first induced. The results demonstrated that treatment with DDP or DMC alone at low concentrations (5 µM) could not inhibit A549/DDP cell proliferation. However, DDP (10 and 20 µM) in combination with DMC enhanced the sensitivity of A549/DDP cells to DDP. Nevertheless, this effect was not robust when cells were treated with 3.8 µM of DDP, which was the IC50 value of DDP in non-resistant A549 cells. These results suggested that DMC decreased DDP resistance of A549/DDP cells; however, DDP resistance was not completely restored. Unfortunately, only one cell line was used in the present study, which is a limitation. Further investigation using additional cell lines would confirm the results from the present study.

Weakening the DNA damage repair capacity is one of the important mechanisms of DDP resistance in cancer cells (41). ERCC1 exerts an essential function at the 5′ site of impaired DNA, whereas hyperexpression of ERCC1 in cancer cells is associated with the removal of DDP adducts from genomic DNA and drug resistance (25). ERCC1 is considered as a key therapeutic target for lung cancer treatment. It has been demonstrated that targeting ERCC1 can recover treatment sensitivity to platinum-based drugs (25). Numerous studies have reported the mechanisms underlying the effects of DMC in combination with DDP treatment in enhanced DDP sensitivity. A study demonstrated that combined administration of CMN and DDP can increase DDP cytotoxicity in cancer cells by downregulating the expression of thymidine phosphorylase (TP) and ERCC1, as well as inactivating the ERK1/2 signaling pathway (42). Another study demonstrated that enhanced DDP cytotoxicity, when the drug is administrated in combination with DMC, is regulated via the PI3K-Akt-Snail pathway and induced by downregulating the expression of TP and ERCC1 (43). Consistent with the previous study, the present study demonstrated that ERCC1 expression was significantly decreased in the combination group compared with that in the DMC treatment group. This finding suggested that ERCC1 upregulation may increase A549/DDP cell sensitivity to DDP. Furthermore, combination treatment enhanced the inhibitory effect of DDP on A549/DDP cells and promoted apoptosis. Finally, the results obtained by comparing tumor size and weight among different treatment groups suggested that the combined drug group exhibited marked therapeutic effects in vivo compared with the monotherapy groups (DMC or DDP alone), indicating, therefore, that DMC may function in vivo.

The results from the present study indicated that DDP in combination with DMC may restore DDP sensitivity in DDP-resistant NSCLC cells. Therefore, co-treatment of DMC with chemotherapeutic drugs may be considered as an attractive approach to overcome drug resistance in patients with NSCLC.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by Zhejiang Province Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Program (grant no. 2016ZA030).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

ZQ and YC designed and performed the experiments. YC performed the in vitro experiments and wrote the manuscript. CH performed the in vivo experiments. XC analyzed data and modified the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Nanjing Medical University (approval no. IACUC-1907009).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Nasim F, Sabath BF, Eapen GA. Lung cancer. Med Clin North Am. 2019;103:463–473. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2018.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peters S, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Gadgeel S, Ahn JS, Kim DW, Ou SI, Pérol M, Dziadziuszko R, Rosell R, et al. Alectinib versus crizotinib in untreated ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:829–838. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1704795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rinaldi M, Cauchi C, Gridelli C. First line chemotherapy in advanced or metastatic NSCLC. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(Suppl 5):v64S–v67S. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ke B, Wei T, Huang Y, Gong Y, Wu G, Liu J, Chen X, Shi L. Interleukin-7 resensitizes non-small-cell lung cancer to cisplatin via inhibition of ABCG2. Mediators Inflamm. 2019;2019:7241418. doi: 10.1155/2019/7241418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galluzzi L, Senovilla L, Vitale I, Michels J, Martins I, Kepp O, Castedo M, Kroemer G. Molecular mechanisms of cisplatin resistance. Oncogene. 2012;31:1869–1883. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amable L. Cisplatin resistance and opportunities for precision medicine. Pharmacol Res. 2016;106:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janyou A, Changtam C, Suksamrarn A, Tocharus C, Tocharus J. Suppression effects of O-demethyldemethoxycurcumin on thapsigargin triggered on endoplasmic reticulum stress in SK-N-SH cells. Neurotoxicology. 2015;50:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simental-Mendia LE, Pirro M, Gotto AM, Jr, Banach M, Atkin SL, Majeed M, Sahebkar A. Lipid-modifying activity of curcuminoids: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2019;59:1178–1187. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2017.1396201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benediktsdottir BE, Baldursson O, Gudjonsson T, Tonnesen HH, Masson M. Curcumin, bisdemethoxycurcumin and dimethoxycurcumin complexed with cyclodextrins have structure specific effect on the paracellular integrity of lung epithelia in vitro. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2015;4:405–410. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrep.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan F, Dong H, Gong J, Wang D, Hu M, Huang W, Fang K, Qin X, Qiu X, Yang X, Lu F. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the effects of turmeric and curcuminoids on blood lipids in adults with metabolic diseases. Adv Nutr. 2019;10:791–802. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmz021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imran M, Ullah A, Saeed F, Nadeem M, Arshad MU, Suleria HAR. Cucurmin, anticancer, & antitumor perspectives: A comprehensive review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2018;58:1271–1293. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2016.1252711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al Ayoub Y, Gopalan RC, Najafzadeh M, Mohammad MA, Anderson D, Paradkar A, Assi KH. Development and evaluation of nanoemulsion and microsuspension formulations of curcuminoids for lung delivery with a novel approach to understanding the aerosol performance of nanoparticles. Int J Pharm. 2019;557:254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adiwidjaja J, McLachlan AJ, Boddy AV. Curcumin as a clinically-promising anti-cancer agent: Pharmacokinetics and drug interactions. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2017;13:953–972. doi: 10.1080/17425255.2017.1360279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shanmugam MK, Rane G, Kanchi MM, Arfuso F, Chinnathambi A, Zayed ME, Alharbi SA, Tan BK, Kumar AP, Sethi G. The multifaceted role of curcumin in cancer prevention and treatment. Molecules. 2015;20:2728–2769. doi: 10.3390/molecules20022728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hassanalilou T, Ghavamzadeh S, Khalili L. Curcumin and gastric cancer: A review on mechanisms of action. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2019;50:185–192. doi: 10.1007/s12029-018-00186-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mendonca LM, Machado Cda S, Teixeira CC, Freitas LA, Bianchi ML, Antunes LM. Comparative study of curcumin and curcumin formulated in a solid dispersion: Evaluation of their antigenotoxic effects. Genet Mol Biol. 2015;38:490–498. doi: 10.1590/S1415-475738420150046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quitschke WW. Differential solubility of curcuminoids in serum and albumin solutions: Implications for analytical and therapeutic applications. BMC Biotechnol. 2008;8:84. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-8-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen G, Chen Y, Yang N, Zhu X, Sun L, Li G. Interaction between curcumin and mimetic biomembrane. Sci China Life Sci. 2012;55:527–532. doi: 10.1007/s11427-012-4317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hatamipour M, Ramezani M, Tabassi SAS, Johnston TP, Sahebkar A. Demethoxycurcumin: A naturally occurring curcumin analogue for treating non-cancerous diseases. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:19320–19330. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JW, Hong HM, Kwon DD, Pae HO, Jeong HJ. Dimethoxycurcumin, a structural analogue of curcumin, induces apoptosis in human renal carcinoma caki cells through the production of reactive oxygen species, the release of cytochrome C, and the activation of caspase-3. Korean J Urol. 2010;51:870–878. doi: 10.4111/kju.2010.51.12.870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ni X, Zhang A, Zhao Z, Shen Y, Wang S. Demethoxycurcumin inhibits cell proliferation, migration and invasion in prostate cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2012;28:85–90. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ko YC, Lien JC, Liu HC, Hsu SC, Lin HY, Chueh FS, Ji BC, Yang MD, Hsu WH, Chung JG. Demethoxycurcumin-induced DNA damage decreases DNA Repair-associated protein expression levels in NCI-H460 human lung cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:2691–2698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ko YC, Lien JC, Liu HC, Hsu SC, Ji BC, Yang MD, Hsu WH, Chung JG. Demethoxycurcumin induces the apoptosis of human lung cancer NCI-H460 cells through the mitochondrial-dependent pathway. Oncol Rep. 2015;33:2429–2437. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang HB, Chen BH. Inhibition of lung cancer cells A549 and H460 by curcuminoid extracts and nanoemulsions prepared from Curcuma longa linnaeus. Int J Nanomedicine. 2015;10:5059–5080. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S87225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McNeil EM, Melton DW. DNA repair endonuclease ERCC1-XPF as a novel therapeutic target to overcome chemoresistance in cancer therapy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:9990–10004. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams JM, Cory S. The Bcl-2 protein family: Arbiters of cell survival. Science. 1998;281:1322–1326. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ashkenazi A, Fairbrother WJ, Leverson JD, Souers AJ. From basic apoptosis discoveries to advanced selective BCL-2 family inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:273–284. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rheaume E, Cohen LY, Uhlmann F, Lazure C, Alam A, Hurwitz J, Sékaly RP, Denis F. The large subunit of replication factor C is a substrate for caspase-3 in vitro and is cleaved by a caspase-3-like protease during Fas-mediated apoptosis. EMBO J. 1997;16:6346–6354. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.21.6346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rotolo F, Dunant A, Le Chevalier T, Pignon JP, Arriagada R, IALT Collaborative Group Adjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy in nonsmall-cell lung cancer: New insights into the effect on failure type via a multistate approach. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:2162–2166. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ricci S, Antonuzzo A, Galli L, Tibaldi C, Bertuccelli M, Lopes Pegna A, Petruzzelli S, Bonifazi V, Orlandini C, Franco Conte P. A randomized study comparing two different schedules of administration of cisplatin in combination with gemcitabine in advanced nonsmall cell lung carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;89:1714–1719. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001015)89:8<1714::AID-CNCR10>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moldvay J, Rokszin G, Abonyi-Toth Z, Katona L, Kovacs G. Analysis of drug therapy of lung cancer in Hungary. Magy Onkol. 2013;57:33–38. (In Hungarian) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bayat Mokhtari R, Homayouni TS, Baluch N, Morgatskaya E, Kumar S, Das B, Yeger H. Combination therapy in combating cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:38022–38043. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hung CM, Su YH, Lin HY, Lin JN, Liu LC, Ho CT, Way TD. Demethoxycurcumin modulates prostate cancer cell proliferation via AMPK-induced down-regulation of HSP70 and EGFR. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:8427–8434. doi: 10.1021/jf302754w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheu MJ, Lin HY, Yang YH, Chou CJ, Chien YC, Wu TS, Wu CH. Demethoxycurcumin, a major active curcuminoid from Curcuma longa, suppresses balloon injury induced vascular smooth muscle cell migration and neointima formation: An in vitro and in vivo study. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2013;57:1586–1597. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201200462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Teng YN, Hsieh YW, Hung CC, Lin HY. Demethoxycurcumin modulates human P-glycoprotein function via uncompetitive inhibition of ATPase hydrolysis activity. J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63:847–855. doi: 10.1021/jf5042307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruiz de Porras V, Bystrup S, Martinez-Cardus A, Pluvinet R, Sumoy L, Howells L, James MI, Iwuji C, Manzano JL, Layos L, et al. Curcumin mediates oxaliplatin-acquired resistance reversion in colorectal cancer cell lines through modulation of CXC-Chemokine/NF-KB signalling pathway. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24675. doi: 10.1038/srep24675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao S, Pi C, Ye Y, Zhao L, Wei Y. Recent advances of analogues of curcumin for treatment of cancer. Eur J Med Chem. 2019;180:524–535. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Changtam C, Hongmanee P, Suksamrarn A. Isoxazole analogs of curcuminoids with highly potent multidrug-resistant antimycobacterial activity. Eur J Med Chem. 2010;45:4446–4457. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen YY, Lin YJ, Huang WT, Hung CC, Lin HY, Tu YC, Liu DM, Lan SJ, Sheu MJ. Demethoxycurcumin-Loaded chitosan nanoparticle downregulates DNA repair pathway to improve cisplatin-induced apoptosis in non-small cell lung cancer. Molecules. 2018;23:3217. doi: 10.3390/molecules23123217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu H, Luo H, Zhang W, Shen Z, Hu X, Zhu X. Molecular mechanisms of cisplatin resistance in cervical cancer. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2016;10:1885–1895. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S106412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vikhanskaya F, Marchini S, Marabese M, Galliera E, Broggini M. P73a overexpression is associated with resistance to treatment with DNA-damaging agents in a human ovarian cancer cell line. Cancer Res. 2001;61:935–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsai MS, Weng SH, Kuo YH, Chiu YF, Lin YW. Synergistic effect of curcumin and cisplatin via down-regulation of thymidine phosphorylase and excision repair cross-complementary 1 (ERCC1) Mol Pharmacol. 2011;80:136–146. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.071316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin CY, Hung CC, Wang CCN, Lin HY, Huang SH, Sheu MJ. Demethoxycurcumin sensitizes the response of non-small cell lung cancer to cisplatin through downregulation of TP and ERCC1-related pathways. Phytomedicine. 2019;53:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.