Abstract

Background

The rapid worldwide spread of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic has placed patients with pre-existing conditions at risk of severe morbidity and mortality. The present study investigated the clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with severe COVID-19 and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Material/Methods

This study enrolled 336 consecutive patients with confirmed severe COVID-19, including 28 diagnosed with COPD, from January 20, 2020, to April 1, 2020. Demographic data, symptoms, laboratory values, comorbidities, and clinical results were measured and compared in survivors and non-survivors.

Results

Patients with severe COVID-19 and COPD were older than those without COPD. The proportions of men, of patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) and of those requiring invasive ventilation were significantly higher in patients with than without COPD. Leukocyte and neutrophil counts, as well as the concentrations of NT-proBNP, hemoglobin, D-dimer, hsCRP, ferritin, IL-2R, TNF-α and procalcitonin were higher, whereas lymphocyte and monocyte counts were lower, in patients with than without COPD. Of the 28 patients with COPD, 22 (78.6%) died, a rate significantly higher than in patients without COPD (36.0%). A comparison of surviving and non-surviving patients with severe COVID-19 and COPD showed that those who died had a longer history of COPD, more fatigue, and a higher ICU occupancy rate, but a shorter average hospital stay, than those who survived.

Conclusions

COPD increases the risks of death and negative outcomes in patients with severe COVID-19.

MeSH Keywords: COVID-19; Outcome Assessment (Health Care); Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive

Background

Since December 2019, the sudden outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has become a prominent public health emergency worldwide, with severe negative effects, including high death rates and major economic disruptions [1]. As of May 1, 2020, 215 countries and regions had reported cases of viral infection, with over 3.2 million confirmed cases and over 234 000 deaths due to COVID-19 worldwide [2]. Factors associated with the risks of severe disease and death include older age, male sex, smoking, and comorbidities [3].

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is common in China, estimated in 2020 to affect 13.7% of individuals aged >40 years [4]. Most patients affected by this disease are elderly men who have smoked for a long time. COPD is often associated with other systemic diseases and can lead to disordered pulmonary ventilation and even ventilation dysfunction. COPD can therefore increase the risk of infection and further complicate the treatment of patients with severe pulmonary infections. These findings suggested that COPD may increase the risks of severe COVID-19 infection and death.

The most common comorbidities associated with poor prognosis in patients with COVID-19 include hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, respiratory disease, pregnancy, kidney disease, and malignancy [5]. To date, however, less is known about the relationship between clinical presentation and prognosis in patients with severe COVID-19 and COPD [6]. The present study therefore analyzed the clinical characteristics of patients with severe COVID-19 and COPD and determined the relationship between COPD and the prognosis of patients with severe COVID-19.

Material and Methods

Ethics statement

The study was carried out in strict compliance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Tongji Medical College Ethics Committee at Tongji Hospital and the Huazhong University of Science and Technology Committee. All the patients provided oral informed consent.

Study design and population

This study included all patients hospitalized with severe COVID-19 at Tongji Hospital, Wuhan, China, from January 20, 2020, to April 10, 2020. Severe COVID-19 was defined as positivity for SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid by real-time PCR or positivity for SARS-CoV-2-specific IgM and IgG antibodies and at least one of the following manifestations: respiratory rate (RR) ≥30/min, oxygen saturation ≤93% in a resting state, PaO2/FiO2 ≤300 mmHg, pulmonary imaging (CT/DR) showing significant progression >50% within 24 to 48 hours, respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation, shock, or admission to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for failure of other organs [7]. Patients with a previous history of COPD were defined as those with a long history of smoking, a diagnosis of COPD at our hospital, and treatment with inhaled drugs.

Data collection

Data collected from the medical records of each patient included age, sex, duration of COPD, treatment for COPD, comorbidities, and symptoms that included fever, sputum, dyspnea, cough, fatigue, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Laboratory parameters included routine blood tests; tests of liver, renal, and blood coagulation function; and concentrations of brain natriuretic peptide, troponin I, interleukin 2 receptor, C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, interleukin 6, interleukin 8, interleukin 10, and tumor necrosis factor-α. Also recorded were sepsis-related organ failure assessment (SOFA) score [8], patient outcomes, and length of stay in the hospital.

Statistical analysis

Because the incidence and prevalence of COVID-19 in COPD patients were unknown, sample size could not be calculated prior to the study. Normally distributed continuous variables were reported as the mean±SEM and compared by independent t-tests. Non-normally distributed continuous variables were reported as median (first and third quartiles) and compared by Mann-Whitney U-tests. Categorical variables were reported as number (%) and compared by chi-square tests. The relationships of clinical factors to death from severe COVID-19 were assessed using a Cox proportional hazards regression model. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were analyzed. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20 software, with P<0.05 defined as statistically significant.

Results

This study enrolled 336 consecutively hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19, including 28 with COPD. The overall median age was 65 (50-77) years but was significantly higher in patients with than without COPD (71 [63–79] years vs. 62 [43–73] years, P<0.001). The proportion of men was also significantly higher in patients with than without COPD (P=0.004). Hypertension was the most common comorbidity in these patients (38.1%), followed by diabetes (23.2%), coronary heart disease (17.6%), cerebrovascular disease (4.5%), cancer (4.1%), chronic kidney disease (2.4%), autoimmune disease (1.2%), and chronic liver disease (0.9%). COPD ranked as the fourth most common comorbidity in these patients with severe COVID-19, at 8.3% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical features of severe COVID-19 patients with and without COPD.

| Total (n=336) | COPD (n=28) | Non-COPD (n=308) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | Number (%) | Number (%) | ||

| Age* | 65 (50–77) | 71 (63–79) | 62 (43–73) | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 201 (59.8) | 24 (85.7) | 177 (57.5) | 0.004 |

| Female | 135 (40.2) | 4 (14.3) | 131 (42.5) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Essential hypertension | 128 (38.1) | 9 (32.1) | 119 (39.3) | 0.458 |

| Diabetes | 78 (23.2) | 5 (17.9) | 73 (23.7) | 0.483 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 59 (17.6) | 10 (35.7) | 49 (15.9) | 0.008 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 15 (4.5) | 4 (14.3) | 11 (3.6) | 0.009 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 8 (2.4) | 2 (7.1) | 6 (1.9) | 0.089 |

| Chronic liver disease | 3 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.0) | 0.597 |

| Malignancy | 14 (4.1) | 2 (7.1) | 12 (3.9) | 0.423 |

| Autoimmune disease | 4 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 4 (1.3) | 0.541 |

| Symptoms | ||||

| Fever | 298 (88.7) | 24 (85.7) | 274 (89.0) | 0.426 |

| Cough | 255 (76.0) | 28 (100) | 227 (73.7) | 0.003 |

| Expectoration | 97 (28.9) | 28 (100) | 69 (22.8) | <0.001 |

| Dyspnea | 203 (60.4) | 28 (100) | 175 (56.8) | <0.001 |

| Fatigue | 161 (47.9) | 20 (71.4) | 141 (46.5) | 0.012 |

| Pectoralgia | 21 (2.4) | 1 (3.6) | 20 (6.6) | 0.5292 |

| Diarrhea | 93 (27.7) | 7 (25.0) | 86 (28.4) | 0.7031 |

| Nausea | 19 (5.7) | 2 (7.1) | 17 (5.6) | 0.7388 |

| Vomiting | 12 (3.6) | 2 (7.1) | 10 (3.3) | 0.2980 |

| SOFA score | 1.98±1.06 | 2.04±1.15 | 1.87±0.94 | 0.0792 |

| ICU patients | 158 (47.0) | 19 (67.9) | 139 (45.4) | 0.0228 |

| Glucocorticoid treatment | 196 (58.3) | 28 (100) | 168 (54.5) | <0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation** | 136 (40.5) | 19 (67.9) | 117 (38.0) | <0.001 |

| Length of hospital stay*** | 14 (8–19) | 11 (6–14) | 14 (10–21) | 0.001 |

| Mortality | 133 (39.6) | 22 (78.6) | 111 (36.0) | <0.001 |

Data reported as median interquartile range (IQR) years;

invasive mechanical ventilation only;

data reported displayed as IQR: days.

ICU – Intensive Care Unit; SOFA score – Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment score. P<0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

The most common symptoms of severe COVID-19 were fever (88.7%), cough (76.0%), dyspnea (60.4%), fatigue (47.9%), and expectoration (28.9%). Cough, expectoration, dyspnea, and fatigue were more common in patients with COPD than in those without COPD. Other symptoms, including diarrhea (27.7%), nausea (5.7%), vomiting (3.6%), and chest pain (2.4%), as well as SOFA scores, did not differ significantly in these 2 groups. Of the 28 patients with severe COVID-19 and COPD, 19 (67.9%) were admitted to the ICU, a rate significantly higher than in patients without COPD (45.4%). All patients with COPD used glucocorticoids, compared with only 54.5% of those without COPD. Similarly, the utilization rates of invasive ventilation were higher in patients with (67.9%) COPD than in those without (38.0%) COPD. In addition, median hospital stay (11 [6–14] days vs. (14 [10–21] days) and mortality rate (78.6% vs. 36.0%) were higher in patients with than without COPD (Table 1).

At admission, COPD patients had higher leukocyte (8.24×109/L vs. 5.72×109/L) and neutrophil (6.78×109/L vs. 3.54×109/L) counts and higher hemoglobin (13.2 vs. 11.3 g/L), NT-proBNP (729 vs. 422 pg/L), D-dimer (4.1 vs. 1.9 mg/L), hsCRP (79.6 vs. 49.1 mg/L), ferritin (1315 vs. 701 mg/L), IL-2R (962 vs. 576 U/mL), TNF-α (14.5 vs. 9.6 ng/L), and PCT (0.21 vs. 0.09 ng/mL) concentrations than the patients without COPD. In contrast, lymphocyte (0.46×109/L vs. 0.71×109/L) and monocyte (0.29×109/L vs. 0.41×109/L) counts were lower in the COPD group. Other laboratory indicators, such as platelet counts, prothrombin times, APTT, liver and kidney function tests, and CK, LDH, IL-6, IL-8 and IL-10 concentrations, did not differ in these 2 groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Laboratory results of severe COVID-19 patients with and without COPD.

| Normal range | COPD (n=28) | Non-COPD (n=308) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |||

| Blood routine | ||||

| Leukocyte count, ×109/L | 3.5–9.5 | 8.24 (5.23–13.67) | 5.72 (4.21–9.18) | 0.001 |

| Neutrophil count, ×109/L | 1.8–6.3 | 6.78 (3.92–10.96) | 3.54 (2.38–7.66) | 0.001 |

| Lymphocyte count, ×109/L | 1.1–3.2 | 0.46 (0.31–0.97) | 0.71 (0.51–1.27) | 0.012 |

| Monocyte count, ×109/L | 0.1–0.6 | 0.29 (0.21–0.47) | 0.41 (0.27–0.57) | 0.006 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 115–150 | 132 (117–146) | 113 (98–134) | 0.026 |

| Platelet count, ×109/L | 125–350 | 171 (125–224) | 178 (128–237) | 0.585 |

| Blood biochemistry | ||||

| ALT, U/L | ≤33 | 26 (15–45) | 23 (14–41) | 0.748 |

| AST, U/L | ≤32 | 36 (22–57) | 32 (19–55) | 0.637 |

| Albumin, g/L | 35–52 | 31 (24–45) | 33 (26–48) | 0.463 |

| UN, mmol/L | 3.1–8.8 | 7.1 (4.8–9.7) | 6.7 (4.0–9.1) | 0.379 |

| Cr, μmol/L | 45–104 | 76 (51–109) | 71 (42–101) | 0.281 |

| CK, U/L | ≤170 | 128 (64–282) | 113 (56–276) | 0.326 |

| LDH, U/L | 135–214 | 427 (342–619) | 459 (354–651) | 0.194 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/L | <285 | 729 (253–2421) | 422 (153–1028) | 0.001 |

| Blood coagulation | ||||

| PT, s | 9–13 | 12.4 (11.5–16.8) | 13.1 (12.2–17.9) | 0.871 |

| APTT, s | 25–31.3 | 32.4 (24.7–36.5) | 28.1 (21.4–30.8) | 0.415 |

| D-dimer, mg/L | 0–0.55 | 4.1 (1.3–16.4) | 1.9 (0.9–11.3) | 0.001 |

| Inflammatory markers | ||||

| hsCRP, mg/L | <1 | 79.6 (43.5–121.4) | 49.1 (32.8–93.2) | 0.001 |

| ESR, mm/H | 0–20 | 29.0 (14.0–55.6) | 33.2 (19.2–61.3) | 0.712 |

| Ferritin, μg/L | 15–150 | 1315 (564–2507) | 701 (278–1980) | 0.001 |

| IL-2R, U/mL | 223–710 | 962 (541–1237) | 576 (489–989) | 0.003 |

| IL-6, ng/L | <7 | 37.8 (10.1–112.8) | 32.1 (6.5–97.3) | 0.312 |

| IL-8, ng/L | <62 | 29.4 (12.1–60.5) | 34.1 (14.6–68.2) | 0.295 |

| IL-10, ng/L | <9.10 | 11.2 (4.1–15.8) | 13.5 (5.3–17.6) | 0.631 |

| TNF-α, ng/L | <8.1 | 14.5 (7.9–22.8) | 9.6 (5.1–13.1) | 0.001 |

| Bacterial infection marker | ||||

| PCT, ng/mL | 0.02–0.05 | 0.21 (0.10–1.15) | 0.09 (0.05–0.18) | 0.001 |

ALT – alanine aminotransferase; AST – aspartate aminotransferase; UN – urea nitrogen; Cr – creatinine; CK – creatine kinase; LDH – lactic dehydrogenase; PT – prothrombin time; APTT – activated partial thromboplastin time; hsCRP – high sensitive C-reactive protein; IL – interleukin; NT-proBNP – N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; TNF-α – tumor necrosis factor-α; PCT – procalcitonin; ESR – erythrocyte sedimentation rate. P<0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Of the 336 patients with severe COVID-19, 133 (39.6%) died. Compared with survivors, non-survivors were older (69 [57–80] vs. 48 [36–69] years), had a larger proportion of men (59.8% vs. 40.2%), and were more likely to have other diseases, including hypertension (45.9% vs. 33%), diabetes (32.3% vs. 17.2%), cardiovascular disease (27.1% vs. 11.3%), and COPD (16.5% vs. 3.0%) (Table 3). The ICU admission rate (78.9% vs. 26.1%), the use of glucocorticoids (91.0% vs. 37.0%), SOFA scores (<0.001), and the need for mechanical ventilation support (92.5% vs. 6.4%) were higher in patients who died, whereas the average length of hospital stay (10 [5–14] days vs. 16 [12–24] days) was significantly shorter (Table 3).

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of survivors and non-survivors with severe COVID-19 patients.

| Total (n=336) | Survivors (n=203) | Non-survivors (n=133) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | Number (%) | Number (%) | ||

| Age* | 65 (50–77) | 48 (36–69) | 69 (57–80) | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 201 (59.8) | 100 (49.3) | 101 (75.9) | <0.001 |

| Female | 135 (40.2) | 103 (50.7) | 32 (24.1) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| COPD | 28 (8.3) | 6 (3.0) | 22 (16.5) | <0.001 |

| Essential hypertension | 128 (38.1) | 67 (33.0) | 61 (45.9) | 0.018 |

| Diabetes | 78 (23.2) | 35 (17.2) | 43 (32.3) | 0.001 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 59 (17.6) | 23 (11.3) | 36 (27.1) | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 15 (4.5) | 7 (3.4) | 8 (6.0) | 0.265 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 8 (2.4) | 5 (2.5) | 3 (2.3) | 0.903 |

| Chronic liver disease | 3 (0.9) | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.8) | 0.824 |

| Malignancy | 14 (4.1) | 8 (3.9) | 6 (4.5) | 0.798 |

| Autoimmune disease | 4 (1.2) | 3 (1.5) | 1 (0.8) | 0.549 |

| SOFA score | 1.98±1.06 | 1.02±0.93 | 2.46±1.23 | <0.001 |

| ICU patients | 158 (47.0) | 53 (26.1) | 105 (78.9) | <0.001 |

| Glucocorticoid treatment | 196 (58.3) | 75 (37.0) | 121 (91.0) | <0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation** | 136 (40.5) | 13 (6.4) | 123 (92.5) | <0.001 |

| Length of hospital stay*** | 14 (8–19) | 16 (12–24) | 10 (5–14) | <0.001 |

Data reported as IQR, years;

invasive mechanical ventilation only;

data reported as IQR, days.

ICU – Intensive Care Unit; SOFA score – Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment score. P<0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

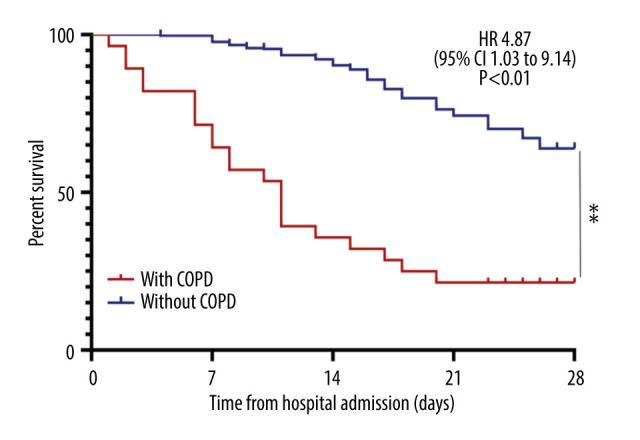

Of the 28 patients with severe COVID-19 and COPD, 22 (78.6%) died. Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that the overall survival rate was worse in severe COVID-19 patients with than without COPD (HR 4.87; 95% CI 1.03 to 9.14, P<0.01; Figure 1). Cox proportional hazard regression analysis showed that the overall survival rate remained worse in severe COVID-19 patients with than without COPD after adjusting for age and sex (HR 2.75; 95% CI 1.01 to 5.67, P=0.018) and after adjusting for hypertension and cardio-cerebrovascular disease (HR 1.98; 95% CI 0.59 to 3.44, P=0.037).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves comparing patients with severe COVID-19 with and without COPD (** P<0.01).

A comparison of survivors and non-survivors in the group with severe COVID-19 and COPD showed that those who died were significantly more likely to be men (P<0.001); to have a longer history of COPD (P=0.032), a higher SOFA score (P<0.001), and a higher likelihood of fatigue (81.8% vs. 33.3%) and to be admitted to the ICU. However, the median length of hospital stay was significantly shorter in patients who died than in those who survived (8 [5–13] days vs. 15 [11–19] days) (Table 4). Moreover, a comparison of survivors and non-survivors in this group showed that leukocyte (9.76×109/L vs. 6.32×109/L) and neutrophil (9.01×109/L vs. 4.66×109/L) counts were higher in non-survivors, as were blood urea nitrogen (9.2 vs. 5.4 mmol/L), creatinine (92 vs. 69 μmol/L), CK (168 vs. 92 U/L), LDH (519 vs. 316 U/L), NT-proBNP (889 v 398 pg/L), D-dimer (7.96 vs. 2.56 mg/L), hsCRP (89.1 vs. 44.3 mg/L), ferritin (1569 vs. 536 mg/L), IL-2R (1024 vs. 712 U/mL), TNF-α (12.6 vs. 6.4 ng/L), and PCT (0.47 vs. 0.14 ng/mL) concentrations. In contrast, lymphocyte (0.44×109/L vs. 0.87×109/L) and monocyte (0.31×109/L vs. 0.52×109/L) counts and albumin levels (25 vs. 33 g/L) were significantly lower in non-survivors (Table 5).

Table 4.

Clinical features of survivors and non-survivors with severe COVID-19 and COPD.

| Total (n=28) | Survivors (n=6) | Non-survivors (n=22) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | Number (%) | Number (%) | ||

| Age# | 70.5±10.6 | 67.8±8.7 | 72.3±11.4 | 0.379 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 24 (85.7) | 4 (66.7) | 20 (90.9) | <0.001 |

| Female | 4 (14.3) | 2 (33.3) | 2 (9.1) | |

| COPD duration* | 5 (3–8) | 3.5 (2–5.5) | 5 (3–8) | 0.0320 |

| COPD treatment | ||||

| None | 7 (25.0) | 3 (50.0) | 4 (18.2) | 0.111 |

| LAMA/LABA | 10 (35.7) | 2 (33.3) | 8 (36.4) | 0.891 |

| ICS+LAMA/LABA | 6 (21.4) | 1 (16.7) | 5 (22.7) | 0.748 |

| Oxygen therapy | 3 (10.7) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (13.6) | 0.338 |

| Ventilatory(NIV) support | 2 (7.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (9.1) | 0.443 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Essential hypertension | 9 (32.1) | 2 (33.3) | 7 (31.8) | 0.944 |

| Diabetes | 5 (17.9) | 2 (33.3) | 3 (13.6) | 0.264 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 10 (35.7) | 3 (50.0) | 7 (31.8) | 0.410 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 4 (14.3) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (13.6) | 0.851 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 2 (7.1) | 2 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.005 |

| Chronic liver disease | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Malignancy | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (9.1) | 0.443 |

| Autoimmune disease | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Symptoms | ||||

| Fever | 24 (85.7) | 4 (66.7) | 20 (90.9) | 0.133 |

| Cough | 28 (100) | 6 (100) | 22 (100) | – |

| Expectoration | 28 (100) | 6 (100) | 22 (100) | – |

| Dyspnea | 28 (100) | 6 (100) | 22 (100) | – |

| Fatigue | 20 (71.4) | 2 (33.3) | 18 (81.8) | 0.020 |

| Pectoralgia | 1 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.5) | 0.595 |

| Diarrhea | 7 (25.0) | 2 (33.3) | 5 (22.7) | 0.595 |

| Nausea | 2 (7.1) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (4.5) | 0.307 |

| Vomiting | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (9.1) | 0.443 |

| SOFA score | 2.04±1.15 | 1.49±1.12 | 3.39±1.47 | <0.001 |

| ICU patients | 19 (67.9) | 2 (33.3) | 17 (77.3) | 0.041 |

| Glucocorticoid treatment | 28 (100) | 6 (100) | 22 (100) | – |

| Mechanical ventilation** | 19 (67.9) | 3 (50.0) | 16 (72.7) | 0.291 |

| Length of hospital stay*** 11 (6–14) | 15 (11–19) | 8 (5–13) | 0.003 | |

Mean±SD, years;

data reported as IQR, years;

invasive mechanical ventilation only;

data reported as IQR, days.

ICU – Intensive Care Unit; SOFA score – Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment score. P<0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Table 5.

Laboratory findings of survivors and non-survivors with severe COVID-19 and COPD.

| Normal range | Survivors (n=6) | Non-survivors (n=22) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |||

| Blood routine | ||||

| Leukocyte count, ×109/L | 3.5–9.5 | 6.32 (3.78–8.14) | 9.76 (4.91–14.54) | 0.003 |

| Neutrophil count, ×109/L | 1.8–6.3 | 4.66 (3.02–6.45) | 9.01 (5.27–13.16) | 0.001 |

| Lymphocyte count, ×109/L | 1.1–3.2 | 0.87 (0.49–1.67) | 0.44 (0.31–0.67) | 0.001 |

| Monocyte count, ×109/L | 0.1–0.6 | 0.52 (0.34–0.77) | 0.31 (0.18–0.55) | 0.016 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 115–150 | 135 (107–166) | 141 (114–175) | 0.486 |

| Platelet count, ×109/L | 125–350 | 173 (120–226) | 182 (134–245) | 0.279 |

| Blood biochemistry | ||||

| ALT, U/L | ≤33 | 21 (14–37) | 24 (18–46) | 0.136 |

| AST, U/L | ≤32 | 34 (21–49) | 35 (22–52) | 0.572 |

| Albumin, g/L | 35–52 | 33 (21–43) | 25 (19–31) | 0.001 |

| BUN, mmol/L | 3.1–8.8 | 5.4 (3.8–7.5) | 9.2 (6.4–13.6) | 0.001 |

| Cr, μmol/L | 45–104 | 69 (42–93) | 92 (57–121) | 0.012 |

| CK, U/L | ≤170 | 92 (45–129) | 168 (86–296) | 0.029 |

| LDH, U/L | 135–214 | 316 (219–427) | 519 (324–755) | 0.001 |

| NT-BNP, pg/L | <285 | 398 (149–998) | 889 (354–2410) | 0.001 |

| Blood coagulation | ||||

| PT, s | 9–13 | 11.9 (9.5–15.8) | 14.2 (10.2–18.5) | 0.061 |

| APTT, s | 25–31.3 | 31.8 (23.5–34.8) | 33.4 (24.9–36.1) | 0.215 |

| D-dimer, mg/L | 0–0.55 | 2.56 (0.8–6.4) | 7.96 (2.9–14.2) | 0.001 |

| Inflammatory markers | ||||

| hsCRP, mg/L | <1 | 44.3 (29.5–87.4) | 89.1 (35.6–129.2) | 0.001 |

| ESR, mm/H | 0–20 | 31.2 (17.0–46.0) | 33.5 (18.1–55.6) | 0.538 |

| Ferritin, μg/L | 15–150 | 536 (249–1645) | 1569 (579–2598) | 0.001 |

| IL-2R, U/mL | 223–710 | 712 (558–915) | 1024 (796–1357) | 0.003 |

| IL-6, ng/L | <7 | 34.2 (8.8–78.5) | 35.9 (9.6–96.7) | 0.479 |

| IL-8 >62 ng/L | <62 | 31.5 (13.3–56.5) | 35.2 (15.6–69.8) | 0.172 |

| IL-10 >9.1 ng/L | <9.10 | 12.4 (5.2–14.6) | 14.9 (6.3–15.7) | 0.324 |

| TNF-α >8.1 ng/L | <8.1 | 6.4 (4.9–11.8) | 12.6 (6.7–17.5) | 0.001 |

| Bacterial infection marker | ||||

| PCT, ng/mL | 0.02–0.05 | 0.14 (0.09–0.28) | 0.47 (0.13–0.58) | 0.001 |

ALT – alanine aminotransferase; AST – aspartate aminotransferase; UN – urea nitrogen; Cr – creatinine; CK – creatine kinase; LDH – lactic dehydrogenase; PT – prothrombin time; APTT – activated partial thromboplastin time; hsCRP – high sensitive C-reactive protein; ESR – erythrocyte sedimentation rate; IL – interleukin; NT-proBNP – N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; TNF-α – tumor necrosis factor-α; PCT – procalcitonin. Data expressed as median interquartile range (IQR). P values in the 2 groups compared by the χ2 test, Fisher’s exact test, or the Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate. P<0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Discussion

Despite the widespread COVID-19 pandemic and the large numbers of infected patients, relatively little is known about the clinical course in patients with severe COVID-19 and COPD [9]. Of the 336 patients with severe COVID-19 included in this study, only 28 (8.3%) had COPD. These patients were older, had more severe inflammation, and were more prone to bacterial infection than patients with severe COVID-19 without COPD. Furthermore, Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated that overall survival was significantly lower in severe COVID-19 patients with COPD than in those without COPD. Our results showed that COPD was strongly associated with poor prognosis and with adverse clinical outcomes such as ICU admission, glucocorticoid use, invasive mechanical ventilation, and death. Comparisons of survivors and non-survivors with severe COVID-19 and COPD showed that non-survivors were older, were more likely to be men and were more likely to be admitted to the ICU than survivors.

Most COPD patients in China are men with a long history of smoking. In addition, more COVID-19 patients are male, as SARS-CoV-2 infection is through the ACE2 receptor, which is expressed at almost 3-fold higher levels in men than in women [10–12]. Long-term exposure to smoke damages the airway intima and induces the proliferation of airway smooth muscle cells, airway remodeling, disordered pulmonary function, and even ventilation disorders [13]. SARS-CoV-2 infection exacerbates previous lung function injury, significantly increasing the rates of ventilator use and ICU admission. Glucocorticoids are widely used to relieve airway inflammation, especially in severely ill patients [14]. However, anatomically small airways are chronically damaged in COPD patients. Because this damage is usually combined with bronchiectasis and obstruction of airway sputum removal, the small airways are more likely to be infected with bacteria, even with extensively drug-resistant bacteria, exacerbating the original severe pulmonary infection [15]. Together, these factors contribute to a high risk of adverse outcomes in patients with severe COVID-19 and COPD.

Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases are more likely to be present in severe COVID-19 patients with than without COPD. These conditions may be due to long-term hypoxia, chronic inflammation, and other factors leading to vascular endothelial injury [16]. Although the clinical features of the 2 groups in the present study were generally similar, cough, expectoration, dyspnea, and fatigue occurred more frequently in patients with than without COPD. However, because of the small sample size, the differences were not statistically significant.

Laboratory test results showed that lymphocyte and monocyte counts were significantly lower, whereas leukocyte and neutrophil counts, as well as hemoglobin and procalcitonin (PCT) levels, were significantly higher, in patients with than without COPD. These results suggested that bacterial infection may have occurred after viral infection. However, the higher hemoglobin concentration in patients with COPD may have been due to a lack of oxygen. In addition, we found that markers of inflammation, such as hsCRP, ferritin, IL-2R, and TNF-α, were higher in patients with than without COPD, as were the rates of coagulation disorders and myocardial injuries. A comparison of surviving and non-surviving patients with severe COVID-19 and COPD found that leukocyte counts, neutrophil counts, and procalcitonin levels were higher, whereas lymphocyte and monocyte counts were lower, in non-survivors. Moreover, there was greater damage to myocardial, hepatic, and renal functions in non-survivors than in survivors. These results indicate that the degree of inflammation is greater in severe COVID-19 patients with than without COPD and that the degree of inflammation is closely related to patient prognosis.

This study has several limitations. First, it was a single-center, retrospective study in a relatively small number of patients, which made it difficult to accurately assess various risk factors using a multifactor regression model. Second, the diagnosis of COPD was based on patient history, not on objective analysis of lung function. Third, this study focused on patients with early-stage COVID-19, indicating the need for studies in the later stages of this disease.

Conclusions

These results indicate that severe COVID-19 patients with COPD have a higher prevalence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, are more likely to receive mechanical ventilation and to be treated in the ICU, and have a higher mortality rate than severe COVID-19 patients without COPD. These results also suggest that, in severe COVID-19 patients, COPD is a high risk factor for poor prognosis. Therefore, COPD patients should be more vigilant to prevent infection with COVID-19. Larger studies with longer follow-up durations are needed to confirm these findings.

Footnotes

Source of support: The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81700051, 81670048, and 81700052), the National Key Technology R&D Program of the 12th National Five-year Development Plan (No. 2012BAI05B01), and the National Key Research and Development Programs of China (No. 2016YFC1304500, 2016-YFC0903600)

References

- 1.WHO main website. 2020. https://www.who.int.

- 2.World Health Organization. Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) situation reports. 2020. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports/

- 3.Horowitz RI, Freeman PR. Three novel prevention, diagnostic, and treatment options for COVID-19 urgently necessitating controlled randomized trials. Med Hypotheses. 2020;143:109851. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagner PD, Viegi G, Luna CM, et al. Major causes of death in China. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(8):874–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc052714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ji HL, Zhao R, Matalon S, Matthay MA. Elevated plasmin(ogen) as a common risk factor for COVID-19 susceptibility. Physiol Rev. 2020;100(3):1065–75. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halpin DMG, Faner R, Sibila O, et al. Do chronic respiratory diseases or their treatment affect the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection? Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):436–38. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30167-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when Novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected: interim guidance. https://www.who.int/internal-publications-detail/clinical-managementof-severe-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected.

- 8.Raith EP, Udy AA, Bailey M, et al. Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society (ANZICS) Centre for Outcomes and Resource Evaluation (CORE) Prognostic accuracy of the SOFA score, SIRS criteria, and qSOFA score for in-hospital mortality among adults with suspected infection admitted to the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2017;317(3):290–300. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.20328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. China Novel Coronavirus Investigation and Research Team. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thachil J, Tang N, Gando S, et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1023–26. doi: 10.1111/jth.14810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, He W, Yu X, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 in elderly patients: Characteristics and prognostic factors based on 4-week follow-up. J Infect. 2020;80(6):639–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: Implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):565–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.López-Campos JL, Tan W, Soriano JB. Global burden of COPD. Respirology. 2016;21(1):14–23. doi: 10.1111/resp.12660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mirza S, Clay RD, Koslow MA, Scanlon PD. COPD guidelines: A review of the 2018 GOLD report. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93(10):1488–502. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cui Y, Luo L, Li C, et al. Long-term macrolide treatment for the prevention of acute exacerbations in COPD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:3813–29. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S181246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deng F, Wang S, Xu R, et al. Endothelial microvesicles in hypoxic hypoxia diseases. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22(8):3708–18. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]